- Subjects: Neurosciences

- |

- Contributor:

- Neuroscientifically Challenged

- Tourette syndrome

- neuroscience

This video is adapted from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8brbjfNX8ck

In this video, I discuss what is hypothesized to occur in the brain to cause Tourette syndrome, a disorder characterized by recurrent involuntary movements or sounds called tics. [1][2][3]

For an article (on my website) that discusses Tourette syndrome more in-depth, click this link: Know Your Brain: Tourette Syndrome (neuroscientificallychallenged.com)

TRANSCRIPT:

Tourette syndrome is characterized by recurrent involuntary movements or sounds called tics. Tics can be classified as simple or complex. Simple tics usually involve only one group of muscles, and might consist of actions like eye blinking or throat clearing. Complex tics are more elaborate, and might involve actions like reaching out to touch something or the involuntary use of obscene language, which is known as coprolalia. It’s worth noting that coprolalia, while often associated with Tourette syndrome, is actually thought to occur in less than 20% of cases.

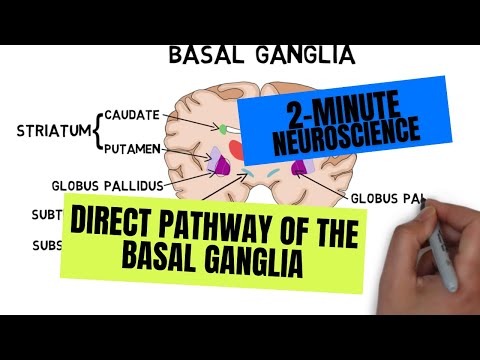

The neuroscience of Tourette syndrome is still poorly understood, but a number of studies suggest an important role for a group of structures known as the basal ganglia, which includes the: caudate, putamen, globus pallidus, substantia nigra, and subthalamic nucleus. The basal ganglia are involved in diverse brain functions, but they are especially relevant to Tourette syndrome for their hypothesized role in suppressing unwanted actions.

According to this perspective, one function of basal ganglia circuitry is to inhibit neurons in the thalamus and prevent them from sending undesired movement-related signals to the motor cortex. In Tourette syndrome, it’s thought that faulty inhibitory mechanisms in the basal ganglia may fail to stop unwanted signals from reaching the cortex. This causes the execution of an action that the patient might prefer to suppress, forming the basis for tics. The failed inhibition in the basal ganglia is thought to be coupled with increased activity in motor pathways that generate movements. Thus, patients with Tourette’s might experience a problematic combination of high motor activity that generates habitual patterns of behavior, along with abnormally low inhibitory activity that would normally keep those behaviors from being acted out. More research needs to be done, however, to fully elucidate the neural circuitry underlying the disorder.

- Jahanshahi M, Obeso I, Rothwell JC, Obeso JA. A fronto-striato-subthalamic-pallidal network for goal-directed and habitual inhibition. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015 Dec;16(12):719-32. doi: 10.1038/nrn4038. Epub 2015 Nov 4.

- McNaught KS, Mink JW. Advances in understanding and treatment of Tourette syndrome. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011 Nov 8;7(12):667-76. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.167.

- Robertson MM, Eapen V, Singer HS, Martino D, Scharf JM, Paschou P, Roessner V, Woods DW, Hariz M, Mathews CA, Črnčec R, Leckman JF. Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017 Feb 2;3:16097. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.97.