Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Agata Stanek | -- | 1581 | 2023-04-17 07:21:55 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 1581 | 2023-04-18 08:16:25 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Stanek, A.; Grygiel-Górniak, B.; Brożyna-Tkaczyk, K.; Myśliński, W.; Cholewka, A.; Zolghadri, S. Arterial Stiffness among Overweight and Obese Subjects. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43101 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Stanek A, Grygiel-Górniak B, Brożyna-Tkaczyk K, Myśliński W, Cholewka A, Zolghadri S. Arterial Stiffness among Overweight and Obese Subjects. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43101. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Stanek, Agata, Bogna Grygiel-Górniak, Klaudia Brożyna-Tkaczyk, Wojciech Myśliński, Armand Cholewka, Samaneh Zolghadri. "Arterial Stiffness among Overweight and Obese Subjects" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43101 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Stanek, A., Grygiel-Górniak, B., Brożyna-Tkaczyk, K., Myśliński, W., Cholewka, A., & Zolghadri, S. (2023, April 17). Arterial Stiffness among Overweight and Obese Subjects. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/43101

Stanek, Agata, et al. "Arterial Stiffness among Overweight and Obese Subjects." Encyclopedia. Web. 17 April, 2023.

Copy Citation

It is known that arterial stiffness increases among obese and overweight individuals, especially with excess abdominal fat. Increased arterial stiffness contributes to the development of hypertension, due to structural modifications in the vessels and changes in their elasticity, capacity, and resistance, with a consequent loss of vascular compliance.

overweight

obesity

arterial stiffness

diet

1. Introduction

Currently, obesity is a serious chronic disease, which constitutes not only a health problem but also a social and economic one. The number of overweight and obese subjects is still increasing. This is why the global nature of the obesity epidemic was recognized by the WHO, in 1997. In 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that there are about 2 billion adults who are overweight, whilst 650 million are obese. It is expected that 2.7 billion adults will be overweight, and over 1 billion will be obese by 2025 if these rates do not slow down [1][2].

Both being overweight and obese have a huge impact on the development of many diseases such as nonalcoholic fatty liver, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease (CVD), hypertension and stroke, various forms of cancer, musculoskeletal diseases, chronic kidney disease, sleep apnea, as well as mental health problems. Additionally, overweight and obese subjects are also about three times more likely to be hospitalized for COVID-19. They also have an increased risk of intensive care unit admission, invasive mechanical ventilation, and death [1][2][3][4][5].

Additionally, it has been shown that subjects with obesity are likely to have an increase in aortic stiffness, independent of blood pressure level, ethnicity, and age [6]. Moreover, arterial stiffness is often increased in overweight/obese subjects before the development of hypertension [7]. In their study, Kim HL et al. have shown that arterial stiffness may be more strongly associated with abdominal obesity than with overall obesity [8]. It has also been shown that body fat percentage is directly associated with arterial stiffness in long-lived populations, consistent with individuals with lean muscle having more elastic arteries [9]. An increase of two percentage points in the average BMI of society reduces the average life expectancy by one year [10].

Arterial stiffness is an independent risk factor, contributing to the development, progression, and mortality of CVD. It is also one of the earliest indicators of increased CVD risk and can be considered a good predictor of the development of subclinical cardiovascular dysfunction [11][12]. Furthermore, on the one hand, arterial stiffness increases with cardiovascular ageing, but on the other hand, it may be accelerated and occurs earlier in the presence of obesity, insulin resistance, and diabetes [13]. However, increased arterial stiffness is also observed in young people (age 10–24 years) with obesity and obesity-related type 2 diabetes mellitus and is an independent predictor of arterial stiffness even after adjusting for cardiovascular risk factors [14]. Furthermore, the development of vascular stiffness due to obesity is more common in women than in men, and obese and insulin-resistant women lose the protection of the CVD associated with estrogen [15].

Being overweight and obese is related to arterial stiffness and is associated with hypertension. Interestingly, isolated systolic hypertension with high arterial stiffness responds weakly to antihypertensive drugs. As a result, the velocity of the aortic pulse wave (PWV) does not reduce significantly after hypotensive management [16]. A lower response to pharmacological treatment is observed in patients with a high grade of arterial stiffness than in subjects with more distensible arteries. In such cases, non-pharmacological interventions can be beneficial. The study by Dengo et al. has shown that reduced body mass during four months in overweight and obese patients significantly improves aortic and carotid stiffness [17]. Thus, dietary interventions leading to body mass reduction are required to decrease arterial stiffness significantly by improving neuromodulation and blood pressure control [18][19][20].

2. Arterial Stiffness among Overweight and Obese Subjects

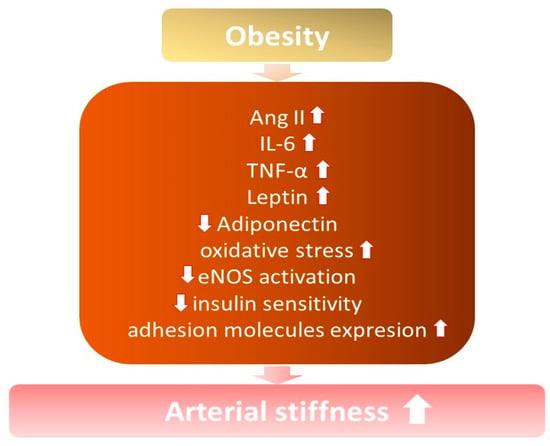

It is known that arterial stiffness increases among obese and overweight individuals, especially with excess abdominal fat [7][21][22] (Figure 1). Increased arterial stiffness contributes to the development of hypertension, due to structural modifications in the vessels and changes in their elasticity, capacity, and resistance, with a consequent loss of vascular compliance [14].

Figure 1. The influence of obesity on the development of increased arterial stiffness. ↓—decrease; ↑ —increase; Ang II—angiotensin II; IL-6—interleukin 6; TNF-α—tumor necrosis factor; eNOS—endothelial nitric oxide synthase.

3.1. Inflammatory Mediators

Interleukin 6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) are the main inflammatory factors, whose level is elevated among obese patients. IL-6 is produced by different cells such as adipocytes and macrophages, which infiltrate adipose tissue and endothelial cells, while TNF—α is primarily a product of macrophages [23][24]. Both contribute to insulin resistance and impaired insulin metabolic signaling, which is crucial for normal endothelial functioning, which is explained below [25].

IL-6 is involved in the regulation of endothelial function by improving the upregulation of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), which have pro-atherogenic facilities [24]. Moreover, IL-6 turned out to be a stimulant of production matrix metalloproteinases, which cause plaque ruptures and changes in arterial vulnerability [26]. Monoclonal antibodies are becoming more and more popular for their therapeutic purposes, especially the IL-6 antagonist, which was widely used during the COVID-19 pandemic [27]. The treatment of atherosclerosis by IL-6 antagonist—tocilizumab—is controversial, while on the one hand, the endothelial function is improved, and arterial stiffness is reduced [28]. On the other hand, the use of tocilizumab in lymphoproliferative disorders causes weight gain and dyslipidemia, which are commonly known as the main risk factors for atherosclerosis [29]. TNF-α, similarly to IL-6, is responsible for the stimulation of VCAM-, ICAM-1, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) production and consequent endothelial dysfunction induced by the synthesis of ROS and inflammatory factors [30]. Treatment with TNF- α antagonist—infliximab—on rodents resulted in a reduction in inflammatory state and protection against insulin resistance and diet-induced obesity [31]. In contrast, studies conducted among participants with insulin resistance did not confirm a positive influence on insulin sensitivity and endothelial function; however, the inflammatory state was reduced [32]. However, obesity is connected with a chronic low-grade inflammatory state, which is confirmed by an increased level of inflammatory markers, especially C-reactive protein, and IL-6, which are significantly higher among obese nonmorbid patients and positively correlate with BMI [33][34].

3.2. Hyperinsulinemia

It is known that obesity, or even overweight, causes impaired insulin release, with hyperinsulinemia, in the beginning, causing the gradual worsening function of β cells of islets of Langerhans. Normal insulin metabolism plays an essential role in maintaining proper endothelial function [18]. Hyperinsulinemia, which is the result of insulin resistance, causes decreased activation of eNOS through an insulin receptor substrate (IRS)-1/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling/protein kinase B (Akt)-mediated pathway, a decrease in NO bioavailability, and a consequent increase in arterial stiffness [35]. Moreover, there is a correlation between hyperinsulinemia and impaired tissue transglutaminase (TG2) functioning in developing arterial stiffness. Increased TG2 activation induces remodeling and increased resistance in arteries. Additionally, it decreases the bioavailability of NO as a result of impaired S-nitrosylation of TG2 and increased excretion to the cell surface [35].

3.3. Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System Activation

Obesity, mainly caused by excess energy intake, especially due to a diet that is not rich in carbohydrates and a high-fructose diet, is associated with increased angiotensin II (ANG II) production by different types of adipose tissue, visceral as well as perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT) [36]. Ang II induces vasoconstriction of vessels and, in increased concentrations, is responsible for the activation of immune cells and the consequent production of cytokines and inflammatory factors [37]. Moreover, increased ANG II causes disturbances in phosphorylation and activation of eNOS through IRS-1/2/PI3K/AKT signaling, which causes decreased production and bioavailability of NO [38]. In addition, Ang II induces enhanced production and release of endothelium-dependent vasoconstrictor, especially endothelin-1 by increased preproendothelin-1, which is consequently changed into endothelin-1, and COX-1-prostanoid by endothelial cells [39][40]. In addition, the role of angiotensin-II type 1 receptors (AT1R) and angiotensin-II type 2 receptors (AT2R) in maintaining proper endothelial function is important. Both receptors are expressed in vascular endothelial cells, while activation of AT1R induces vasoconstriction, and activation of AT2R promotes vasodilation [38]. Persistent activation of AT1R by ANG II induces a decrease in eNOS expression and a consequent decrease in NO concentration. Increased ANG II induces impaired insulin-mediated NO synthesis via up activation of AT1R [38]. Moreover, Ang II, such as aldosterone, increases arterial stiffness by promoting the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), fibrosis, and increased collagen deposition [41].

3.4. Adipocyte-Derived Factors

The synthesis and release of factors derived from adipocytes by visceral as well as PVAT are impaired among obese patients. In addition to the factors mentioned above, there is an important change in the production and release of adiponectin and leptin [42][43].

Almabrouk et al. presented their study with mice fed a high-fat diet, and the level of adiponectin was reduced by 70% [44]. There are some data on humans which confirm the point of view that obesity decreases the level of adiponectin, and the relationship between the level of adiponectin and arterial stiffness is inversely proportional [42][43][45]. Furthermore, among obese patients, the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ), which is responsible for the differentiation of adipocytes, is down-regulated, causing a decrease in adiponectin [46]. As a consequence, the anticontractile effect of adiponectin, caused by the activation of adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and consequent phosphorylation of eNOS, is weakened.

The level of leptin among obese patients is enhanced, while the synthesis of leptin by adipocytes is directly proportional to its size [43]. Leptin has anticontractile properties by increasing NO synthesis; however, prolonged exposure of the endothelium to leptin causes a decrease in NO bioavailability and a consequent inverse effect on vascular tone [47]. In addition, leptin provokes platelet aggregation and atherothrombosis, stimulates ROS synthesis, and causes consequent endothelial dysfunction, resulting in increased arterial stiffness [48][49].

References

- WHO. World Obesity Day 2022-Accelerating Action to Stop Obesity. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/04-03-2022-world-obesity-day-2022-accelerating-action-to-stop-obesity (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Boutari, C.; Mantzoros, C.S. A 2022 update on the epidemiology of obesity and a call to action: As its twin COVID-19 pandemic appears to be receding, the obesity and dysmetabolism pandemic continues to rage on. Metabolism 2022, 133, 55217.

- Stanek, A.; Brożyna-Tkaczyk, K.; Myśliński, W. The Role of Obesity-Induced Perivascular Adipose Tissue (PVAT) Dysfunction in Vascular Homeostasis. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3843.

- Stanek, A.; Brożyna-Tkaczyk, K.; Myśliński, W. Oxidative Stress Markers among Obstructive Sleep Apnea Patients. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2021, 2021, 9681595.

- Rahban, M.; Stanek, A.; Hooshmand, A.; Khamineh, Y.; Ahi, S.; Kazim, S.N.; Ahmad, F.; Muronetz, V.; Abousenna, M.S.; Zolghadri, S.; et al. Infection of Human Cells by SARS-CoV-2 and Molecular Overview of Gastrointestinal, Neurological, and Hepatic Problems in COVID-19 Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4802.

- Safar, M.E.; Czernichow, S.; Blacher, J. Obesity, arterial stiffness, and cardiovascular risk. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006, 17, S109–S111.

- Femia, R.; Kozakova, M.; Nannipieri, M.; Gonzales-Villalpando, C.; Stern, M.P.; Haffner, S.M. Carotid intima-media thickness in confirmed prehypertensive subjects: Predictors and progression. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007, 27, 2244–2249.

- Kim, H.L.; Ahn, D.W.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, D.S.; Yoon, S.H.; Zo, J.H.; Kim, M.A.; Jeong, J.B. Association between body fat parameters and arterial stiffness. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20536.

- Melo E Silva, F.V.; Almonfrey, F.B.; Freitas, C.M.N.; Fonte, F.K.; Sepulvida, M.B.C.; Almada-Filho, C.M.; Cendoroglo, M.S.; Quadrado, E.B.; Amodeo, C.; Povoa, R.; et al. Association of Body Composition with Arterial Stiffness in Long-lived People. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2021, 117, 457–462.

- Peto, R.; Whitlock, G.; Jha, P. Effects of obesity and smoking on US life expectancy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 855–856.

- Fernhall, B.; Agiovlasitis, S. Arterial function in youth: Window into cardiovascular risk. J. Appl. Physiol. 1985, 105, 325–333.

- Starzak, M.; Stanek, A.; Jakubiak, G.K.; Cholewka, A.; Cieślar, G. Arterial Stiffness Assessment by Pulse Wave Velocity in Patients with Metabolic Syndrome and Its Components: Is It a Useful Tool in Clinical Practice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10368.

- Urbina, E.M.; Kimball, T.R.; Khoury, P.R.; Daniels, S.R.; Dolan, L.M. Increased arterial stiffness is found in adolescents with obesity or obesity-related type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Hypertens. 2010, 28, 1692–1698.

- Liao, J.; Farmer, J. Arterisal Stiffness as a Risk Factor for Coronary Artery Disease. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2014, 16, 387.

- Manrique, C.; Lastra, G.; Ramirez-Perez, F.I.; Haertling, D.; DeMarco, V.G.; Aroor, A.R.; Jia, G.; Chen, D.; Barron, B.J.; Garro, M.; et al. Endothelial estrogen receptor-α does not protect against vascular stiffness induced by Western diet in female mice. Endocrinology 2016, 157, 1590–1600.

- Amore, L.; Alghisi, F.; Pancaldi, E.; Pascariello, G.; Cersosimo, A.; Cimino, G.; Bernardi, N.; Calvi, E.; Lombardi, C.M.; Sciatti, E.; et al. Study of endothelial function and vascular stiffness in patients affected by dilated cardiomyopathy on treatment with sacubitril/valsartan. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2022, 12, 125–135.

- Dengo, A.L.; Dennis, E.A.; Orr, J.S.; Marinik, E.L.; Ehrlich, E.; Davy, B.M.; Davy, K.P. Arterial destiffening with weight loss in overweight and obese middle-aged and older adults. Hypertension 2010, 55, 855–8561.

- Aroor, A.R.; Jia, G.; Sowers, J.R. Cellular mechanisms underlying obesity-induced arterial stiffness. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2018, 314, R387–R398.

- Bagheri, S.; Zolghadri, S.; Stanek, A. Beneficial Effects of Anti-Inflammatory Diet in Modulating Gut Microbiota and Controlling Obesity. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3985.

- Stanek, A.; Brożyna-Tkaczyk, K.; Zolghadri, S.; Cholewka, A.; Myśliński, W. The Role of Intermittent Energy Restriction Diet on Metabolic Profile and Weight Loss among Obese Adults. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1509.

- Recio-Rodriguez, J.I.; Gomez-Marcos, M.A.; Patino-Alonso, M.C.; Agudo-Conde, C.; Rodriguez-Sanchez, E.; Garcia-Ortiz, L. Vasorisk group. Abdominal Obesity vs General Obesity for Identifying Arterial Stiffness, Subclinical Atherosclerosis and Wave Reflection in Healthy, Diabetics and Hypertensive. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2012, 12, 3.

- Fu, S.; Luo, L.; Ye, P.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, B.; Zheng, J.; Bai, Y.; Bai, J. Overall and Abdominal Obesity Indicators Had Different Association with Central Arterial Stiffness and Hemodynamics Independent of Age, Sex, Blood Pressure, Glucose, and Lipids in Chinese Community-Dwelling Adults. Clin. Interv. Aging 2013, 8, 1579–1584.

- Cildir, G.; Akıncılar, S.C.; Tergaonkar, V. Chronic Adipose Tissue Inflammation: All Immune Cells on the Stage. Trends. Mol. Med. 2013, 19, 487–500.

- Lima, L.F.; Braga, V.D.A.; Silva, M.E.S.D.F.; Cruz, J.D.C.; Santos, S.H.S.; Monteiro, M.M.D.O.; Balarini, C.D.M. Adipokines, Diabetes and Atherosclerosis: An Inflammatory Association. Front. Physiol. 2015, 6, 304.

- Jonas, M.I.; Kurylowicz, A.; Bartoszewicz, Z.; Lisik, W.; Jonas, M.; Wierzbicki, Z.; Chmura, A.; Pruszczyk, P.; Puzianowska-Kuznicka, M. Interleukins 6 and 15 Levels Are Higher in Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue, but Obesity Is Associated with Their Increased Content in Visceral Fat Depots. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 25817–25830.

- Watanabe, N.; Ikeda, U. Matrix Metalloproteinases and Atherosclerosis. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2004, 6, 112–120.

- WHO Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID-19 Therapies (REACT) Working Group; Shankar-Hari, M.; Vale, C.L.; Godolphin, P.J.; Fisher, D.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Spiga, F.; Savovic, J.; Tierney, J.; Baron, G.; et al. Association between Administration of IL-6 Antagonists and Mortality among Patients Hospitalized for COVID-19: A Meta-Analysis. JAMA 2021, 326, 499–518.

- Protogerou, A.D.; Zampeli, E.; Fragiadaki, K.; Stamatelopoulos, K.; Papamichael, C.; Sfikakis, P.P. A pilot study of endothelial dysfunction and aortic stiffness after interleukin-6 receptor inhibition in rheumatoid arthritis. Atherosclerosis 2011, 219, 734–736.

- Nishimoto, N.; Kanakura, Y.; Aozasa, K.; Johkoh, T.; Nakamura, M.; Nakano, S.; Nakano, N.; Ikeda, Y.; Sasaki, T.; Nishioka, K.; et al. Humanized Anti-Interleukin-6 Receptor Antibody Treatment of Multicentric Castleman Disease. Blood 2005, 106, 2627–2632.

- Urschel, K.; Cicha, I. TNF-alpha; in the Cardiovascular System: From Physiology to Therapy. Int. J. Interf. Cytokine Mediat. Res. 2015, 7, 9–25.

- Li, Z.; Yang, S.; Lin, H.; Huang, J.; Watkins, P.A.; Moser, A.B.; Desimone, C.; Song, X.; Diehl, A.M. Probiotics and Antibodies to TNF Inhibit Inflammatory Activity and Improve Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Hepatology 2003, 37, 343–350.

- Wascher, T.C.; Lindeman, J.H.; Sourij, H.; Kooistra, T.; Pacini, G.; Roden, M. Chronic TNF-α Neutralization Does Not Improve Insulin Resistance or Endothelial Function in “Healthy” Men with Metabolic Syndrome. Mol. Med. 2011, 17, 189–193.

- Sudhakar, M.; Silambanan, S.; Chandran, A.S.; Prabhakaran, A.A.; Ramakrishnan, R. C-Reactive Protein (CRP) and Leptin Receptor in Obesity: Binding of Monomeric CRP to Leptin Receptor. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1167.

- Gnacińska, M.; Małgorzewicz, S.; Guzek, M.; Lysiak-Szydłowska, W.; Sworczak, K. Adipose Tissue Activity in Relation to Overweight or Obesity. Endokrynol. Polska 2010, 61, 160–168.

- Jia, G.; Aroor, A.R.; Sowers, J.R. Arterial Stiffness: A Nexus between Cardiac and Renal Disease. Cardiorenal. Med. 2014, 4, 60–71.

- Aroor, A.R.; Jia, G.; Sowers, J.R. The Role of Tissue Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System in the Development of Endothelial Dysfunction and Arterial Stiffness. Front. Endocrinol. 2013, 4, 161.

- Bredt, D.S.; Snyder, S.H. Isolation of Nitric Oxide Synthetase, a Calmodulin-Requiring Enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 682–685.

- Kim, J.A.; Jang, H.J.; Martinez-Lemus, L.A.; Sowers, J.R. Activation of MTOR/P70S6 Kinase by ANG II Inhibits Insulin-Stimulated Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase and Vasodilation. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 302, E201–E208.

- Kane, M.O.; Etienne-Selloum, N.; Madeira, S.V.F.; Sarr, M.; Walter, A.; Dal-Ros, S.; Schott, C.; Chataigneau, T.; Schini-Kerth, V.B. Endothelium-Derived Contracting Factors Mediate the Ang II-Induced Endothelial Dysfunction in the Rat Aorta: Preventive Effect of Red Wine Polyphenols. Pflugers Arch.-Eur. J. Physiol. 2010, 459, 671–679.

- Kobayashi, T.; Nogami, T.; Taguchi, K.; Matsumoto, T.; Kamata, K. Diabetic State, High Plasma Insulin and Angiotensin II Combine to Augment Endothelin-1-Induced Vasoconstriction via ETA Receptors and ERK. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 155, 974–983.

- Kushibiki, M.; Yamada, M.; Oikawa, K.; Tomita, H.; Osanai, T.; Okumura, K. Aldosterone Causes Vasoconstriction in Coronary Arterioles of Rats via Angiotensin II Type-1 Receptor: Influence of Hypertension. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2007, 572, 182–188.

- Aghamohammadzadeh, R.; Unwin, R.D.; Greenstein, A.S.; Heagerty, A.M. Effects of Obesity on Perivascular Adipose Tissue. Vasorelaxant Function: Nitric Oxide, Inflammation and Elevated Systemic Blood Pressure. J. Vasc. Res. 2016, 52, 299–305.

- Schroeter, M.R.; Eschholz, N.; Herzberg, S.; Jerchel, I.; Leifheit-Nestler, M.; Czepluch, F.S.; Chalikias, G.; Konstantinides, S.; Schäfer, K. Leptin-Dependent and Leptin-Independent Paracrine Effects of Perivascular Adipose Tissue on Neointima Formation. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2013, 33, 980–987.

- Almabrouk, T.A.M.; White, A.D.; Ugusman, A.B.; Skiba, D.S.; Katwan, O.J.; Alganga, H.; Guzik, T.J.; Touyz, R.M.; Salt, I.P.; Kennedy, S. High Fat Diet Attenuates the Anticontractile Activity of Aortic PVAT via a Mechanism Involving AMPK and Reduced Adiponectin Secretion. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 51.

- Mahmud, A.; Feely, J. Adiponectin and Arterial Stiffness. Am. J. Hypertens. 2005, 18, 1543–1548.

- Tontonoz, P.; Spiegelman, B.M. Fat and Beyond: The Diverse Biology of PPAR. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008, 77, 289–312.

- Korda, M.; Kubant, R.; Patton, S.; Malinski, T. Leptin-Induced Endothelial Dysfunction in Obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2008, 295, H1514–H1521.

- Opatrilova, R.; Caprnda, M.; Kubatka, P.; Valentova, V.; Uramova, S.; Nosal, V.; Gaspar, L.; Zachar, L.; Mozos, I.; Petrovic, D.; et al. Adipokines in Neurovascular Diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 98, 424–432.

- Gairolla, J.; Kler, R.; Modi, M.; Khurana, D. Leptin and Adiponectin: Pathophysiological Role and Possible Therapeutic Target of Inflammation in Ischemic Stroke. Rev. Neurosci. 2017, 28, 295–306.

More

Information

Subjects:

Cardiac & Cardiovascular Systems

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

600

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

18 Apr 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No