Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Maria Assunta Zocco | -- | 1371 | 2024-01-08 17:30:01 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | + 3 word(s) | 1374 | 2024-01-10 01:56:18 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Maresca, R.; Varca, S.; Di Vincenzo, F.; Ainora, M.E.; Mignini, I.; Papa, A.; Scaldaferri, F.; Gasbarrini, A.; Giustiniani, M.C.; Zocco, M.A.; et al. Diagnosis of Cytomegalovirus Infection. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/53567 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Maresca R, Varca S, Di Vincenzo F, Ainora ME, Mignini I, Papa A, et al. Diagnosis of Cytomegalovirus Infection. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/53567. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Maresca, Rossella, Simone Varca, Federica Di Vincenzo, Maria Elena Ainora, Irene Mignini, Alfredo Papa, Franco Scaldaferri, Antonio Gasbarrini, Maria Cristina Giustiniani, Maria Assunta Zocco, et al. "Diagnosis of Cytomegalovirus Infection" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/53567 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Maresca, R., Varca, S., Di Vincenzo, F., Ainora, M.E., Mignini, I., Papa, A., Scaldaferri, F., Gasbarrini, A., Giustiniani, M.C., Zocco, M.A., & Laterza, L. (2024, January 08). Diagnosis of Cytomegalovirus Infection. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/53567

Maresca, Rossella, et al. "Diagnosis of Cytomegalovirus Infection." Encyclopedia. Web. 08 January, 2024.

Copy Citation

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is still a matter of concern in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases (IBD) patients, especially regarding the disease’s relapse management. Why IBD patients, particularly those affected by ulcerative colitis, are more susceptible to CMV reactivation is not totally explained, although a weakened immune system could be the reason.

infections

CMV

cytomegalovirus

inflammatory bowel diseases

ulcerative colitis

1. Introduction

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a member of the herpes-virus family, which causes a broad spectrum of human illnesses depending on the host, but most commonly an asymptomatic viral infection (only detectable by serology or viral DNA). Clinically apparent infections (CMV disease) usually present as a mononucleosis-like syndrome but can affect potentially any organ of the human body [1][2].

The epidemiology of CMV infection and colitis varies according to the definition used to diagnose the infection due to the lack of a gold standard definition of clinically relevant CMV infection and CMV intestinal disease, to the severity of colitis, to the studied population, including immunological status, and to the geographical distribution. The highest prevalence of CMV disease is found in studies that used the positive serum polymerase chain reaction (PCR), followed by studies using antigenemia, where the definition of CMV infection is serum CMV replication.

2. Diagnosis of CMV Infection

2.1. Serology

Serological diagnosis of CMV infection relies on detecting specific antibodies the host produces in response to the virus. IgM serology has a sensitivity of between 15 and 60% in detecting CMV in a 2004 study of a cohort of 64 IBD patients, including 10 with CMV infection [3]. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) is the most common serological method used to detect CMV antibodies. In ELISA, viral antigens are immobilized on a solid phase, and patient serum is applied. If specific anti-CMV antibodies are present, they bind to the antigens. Subsequent enzymatic reactions generate a color change, which is quantified to determine the antibody levels [4].

Another essential serological technique is the Immunofluorescence Assay (IFA), which uses fluorescent antibodies to detect CMV-specific immunoglobulins in patient samples [5]. This method is beneficial for confirming positive ELISA results and distinguishing between IgM and IgG antibodies.

Blood serology for CMV has limited diagnostic value for CMV colitis due to the high adult seroprevalence of the virus, as previously mentioned [6].

Therefore, serology has limited utility in diagnosing CMV reactivation in individuals with IBD, only allowing doctors to rule out CMV infection in patients who are negative for anti-CMV antibodies [7].

2.2. Mucosal Biopsies: Immunohistochemistry and PCR

Histological examination of colonic mucosa biopsies is a critical tool for diagnosing CMV infection in IBD patients. Histological assessment of CMV infection in colonic mucosa biopsies involves the examination of tissue samples obtained via endoscopy or surgical procedures [8]. Quality colonoscopy is essential for the diagnostic algorithm of patients with suspected CMV infection, and it must be performed under conditions of adequate bowel preparation. This can be achieved either using oral solutions or using enemas, especially in cases of severe acute ulcerative colitis where rectoscopy allows us to perform sampling for CMV search and rapid endoscopic Mayo score evaluation [9]. The characteristic features of CMV infection in these samples include cytomegalic cells, intranuclear inclusions, and characteristic nuclear and cytoplasmic inclusions [8].

Cytomegalic cells are enlarged cells with characteristic nuclear and cytoplasmic changes. These cells often have large, basophilic intranuclear inclusions indicative of CMV infection. In the cytoplasm, there may be granular or eosinophilic inclusions. The presence of these cytomegalic cells in colonic mucosa biopsies is highly suggestive of CMV infection [10].

Several staining methods can be used to confirm the diagnosis. H&E staining is a standard histological method highlighting the characteristic cellular changes [11]. However, IHC can be even more specific, using antibodies against CMV antigens to identify the virus within infected cells. High specificity [92–100%] can be achieved with H&E staining, while the sensitivity ranges from 10% to 87% [12].

In 2013, Mills et al. showed that CMV-PCR on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue gastrointestinal biopsies complements IHC [13]. In fact, in a total of 102 FFPE gastrointestinal biopsy specimens from 74 patients, CMV DNA was detected via PCR in 90.9% of IHC-positive and 14.5% of IHC-negative tissues. Meanwhile, Kandiel et al. have demonstrated that staining the colonic CMV histology with a particular IHC that is specific to one of the immediate early antigens increases the diagnostic sensitivity [78–93%] and specificity (92–100%) of the examination [14].

Kim et al. identified active gastrointestinal (GI) CMV illness, defined as histological detection of intranuclear inclusion bodies or positive IHC and clinical improvement on ganciclovir treatment, using both interferon γ-releasing assays [IGRA] for CMV and CMV PCR. For predicting gastrointestinal CMV illness, the sensitivity and specificity of the CMV replication in biopsy tissue (positive IHC staining) and low CMV IGRA results were 92% (95% CI = 62–100) and 100% (95% CI = 74–100), respectively [15].

Either way, PCR on GI biopsy tissue is the diagnostic method recommended by the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization (ECCO) for diagnosing CMV colitis in IBD patients [16].

Real-time PCR increases the sensitivity to identify CMV in FFPE tissue of GI biopsies, as demonstrated by McCoy et al. [6]. In their study, qPCR analysis showed positive results in 88 out of the 91 CMV-positive samples that were histologically confirmed, obtaining a sensitivity of 96.7%. In addition, 78 out of the 79 negative controls tested negative via qPCR, yielding a specificity of 98.7%.

Furthermore, in a study published in 2015, Zidar et al. compared immunohistochemistry and qPCR in resected bowel samples from 12 IBD patients [17]. Tissue samples were obtained from different sites of the resected colonic samples. The highest densities of CMV-positive cells were found in samples from the base of ulcers or the edge of ulcers, regardless of the test used and underling the fact that the number of sampled biopsies and/or the number of investigated levels is more important than the choice of diagnostic method [17].

Distinguishing CMV infection from other inflammatory changes in IBD is crucial. Patients with IBD often exhibit histological signs of inflammation in the colon, such as increased numbers of inflammatory cells, architectural distortion, and crypt abscesses. Therefore, these inflammatory changes in colonic mucosa biopsies must be carefully evaluated in the context of CMV diagnosis. A comprehensive assessment should consider the overall clinical presentation and the results of other diagnostic tests, such as PCR-based assays for CMV DNA in blood or tissue.

2.3. Serum and Fecal PCR

PCR-based assays can also detect CMV DNA in blood or other body fluids, providing direct evidence of active viral replication. This approach is highly sensitive and is often used with serological tests for a comprehensive diagnosis.

A prospective study was conducted in 2023 on 117 patients with clinical suspicion of CMV colitis. Compared to colonoscopy and histology, plasma CMV-PCR had a 94.7% specificity and a 66.7% sensitivity [18].

However, according to the ECCO statement regarding IBD patients, this high sensitivity of the PCR assay may lead to inadequate specificity when diagnosing an active CMV infection since it may be able to identify tiny amounts of CMV that are not harmful to the colonic mucosa or the latent form of the virus [19]. To get around this drawback, PCR primers that identify CMV in its reactivated state, but not in its latent form, must be chosen.

A pilot study conducted in 2010 investigated the use of stool PCR in 21 patients with IBD flare-ups unresponsive to steroids. It demonstrated that in comparison to PCR-based CMV detection in mucosal biopsies, the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of the stool test for CMV DNA detection were 83, 93, and 90%, respectively [20].

Ganzenmueller et al. examined 66 patients’ lower intestinal tract biopsies and fecal samples using quantitative CMV PCR. They showed that stool PCR had a good specificity of 96% but a poor sensitivity (67%) for diagnosing CMV intestinal disease [21].

In conclusion, more studies regarding PCR on stool still need to be conducted to determine the true place of this test in the diagnostic algorithm of CMV-related colitis.

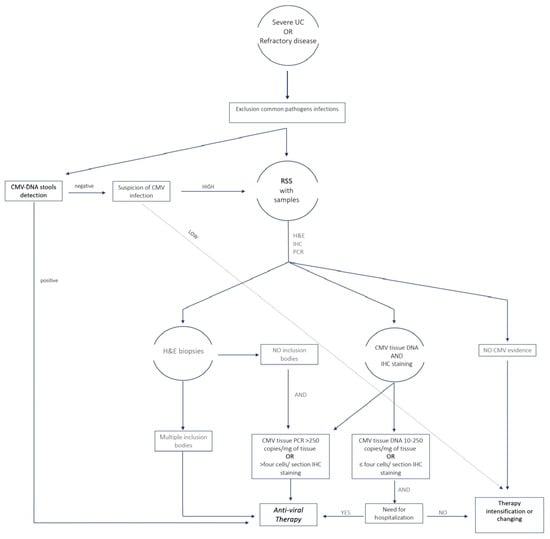

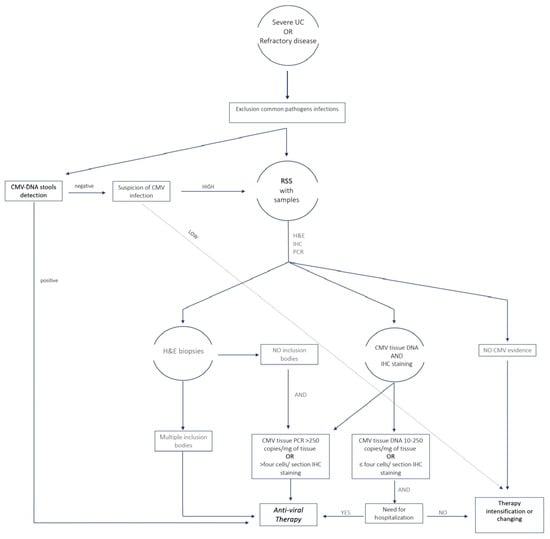

The sensitivity, specificity and strengths of the main diagnostic methods are shown in Table 1. Figure 1 proposes an algorithm that from the diagnosis can direct physicians in selecting patients for treatment.

Figure 1. Algorithm for the diagnosis of CMV infection and selection of patients to treat for clinical practice. UC, ulcerative colitis; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; IHC, immune histochemistry; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; RSS, rectosigmoidoscopy.

Table 1. Sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of diagnostic methods.

| Test | Sens | Spec | Pro |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serology | 15–60% | 96–99% | Easily accessible, fast |

| Serum PCR | 66.7% | 94.7% | Easily accessible, fast |

| Histology w/IHC | 78–93% | 92–100% | Proves intestinal disease |

| Tissue PCR | 96.7% | 98.7% | Proves intestinal disease |

| Fecal PCR | 83–96% | 67–93% | Less invasive |

PCR, polymerase chain reaction; IHC, immune histochemistry.

References

- Landolfo, S.; Gariglio, M.; Gribaudo, G.; Lembo, D. The Human Cytomegalovirus. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003, 98, 269–297.

- Antretter, H.; Höfer, D.; Hangler, H.; Larcher, C.; Pölzl, G.; Hörmann, C.; Margreiter, J.; Margreiter, R.; Laufer, G.; Bonatti, H. Is It Possible to Reduce CMV-Infections after Heart Transplantation with a Three-Month Antiviral Prophylaxis? 7 Years Experience with Ganciclovir. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2004, 116, 542–551.

- Kishore, J.; Ghoshal, U.; Ghoshal, U.C.; Krishnani, N.; Kumar, S.; Singh, M.; Ayyagari, A. Infection with Cytomegalovirus in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Prevalence, Clinical Significance and Outcome. J. Med. Microbiol. 2004, 53, 1155–1160.

- Vainionpää, R.; Leinikki, P. Diagnostic Techniques: Serological and Molecular Approaches. In Encyclopedia of Virology, 3rd ed.; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 29–37.

- Hekker, A.C.; Brand-Saathof, B.; Vis, J.; Meijers, R.C. Indirect Immunofluorescence Test for Detection of IgM Antibodies to Cytomegalovirus. J. Infect. Dis. 1979, 140, 596–600.

- McCoy, M.H.; Post, K.; Sen, J.D.; Chang, H.Y.; Zhao, Z.; Fan, R.; Chen, S.; Leland, D.; Cheng, L.; Lin, J. QPCR Increases Sensitivity to Detect Cytomegalovirus in Formalin-Fixed, Paraffin-Embedded Tissue of Gastrointestinal Biopsies. Hum. Pathol. 2014, 45, 48–53.

- De la Hoz, R.E.; Stephens, G.; Sherlock, C. Diagnosis and Treatment Approaches to CMV Infections in Adult Patients. J. Clin. Virol. 2002, 25, 1–12.

- Azer, S.A.; Limaiem, F. Cytomegalovirus Colitis. StatPearls ; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023.

- Gravina, A.G.; Pellegrino, R.; Romeo, M.; Palladino, G.; Cipullo, M.; Iadanza, G.; Olivieri, S.; Zagaria, G.; De Gennaro, N.; Santonastaso, A.; et al. Quality of Bowel Preparation in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease Undergoing Colonoscopy: What Factors to Consider? World J. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2023, 15, 133–145.

- Wu, G.-D.; Shintaku, I.; Chien, K.; Geller, S. A Comparison of Routine Light Microscopy, Immunohistochemistry, and in Situ Hybridization for the Detection of Cytomegalovirus in Gastrointestinal Biopsies. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1989, 84, 1517–1520.

- Cornaggia, M.; Leutner, M.; Mescoli, C.; Sturniolo, G.C.; Gullotta, R. Chronic Idiopathic Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: The Histology Report. Dig. Liver Dis. 2011, 43 (Suppl. S4), S293–S303.

- Lawlor, G.; Moss, A.C. Cytomegalovirus in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Pathogen or Innocent Bystander? Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2010, 16, 1620–1627.

- Mills, A.M.; Guo, F.P.; Copland, A.P.; Pai, R.K.; Pinsky, B.A. A Comparison of CMV Detection in Gastrointestinal Mucosal Biopsies Using Immunohistochemistry and PCR Performed on Formalin-Fixed, Paraffin-Embedded Tissue. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2013, 37, 995–1000.

- Kandiel, A.; Lashner, B. Cytomegalovirus Colitis Complicating Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 101, 2857–2865.

- Kim, S.H.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, S.M.; Shin, S.; Park, S.H.; Kim, K.J.; Kim, Y.H.; Sung, H.; Lee, S.O.; et al. Clinical Applications of Interferon-γ Releasing Assays for Cytomegalovirus to Differentiate Cytomegalovirus Disease from Bystander Activation: A Pilot Proof-of-Concept Study. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2017, 32, 900.

- Rahier, J.F.; Magro, F.; Abreu, C.; Armuzzi, A.; Ben-Horin, S.; Chowers, Y.; Cottone, M.; de Ridder, L.; Doherty, G.; Ehehalt, R.; et al. Second European Evidence-Based Consensus on the Prevention, Diagnosis and Management of Opportunistic Infections in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Crohns Colitis 2014, 8, 443–468.

- Zidar, N.; Ferkolj, I.; Tepeš, K.; Štabuc, B.; Kojc, N.; Uršič, T.; Petrovec, M. Diagnosing Cytomegalovirus in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease--by Immunohistochemistry or Polymerase Chain Reaction? Virchows Arch. 2015, 466, 533–539.

- Sattayalertyanyong, O.; Limsrivilai, J.; Phaophu, P.; Subdee, N.; Horthongkham, N.; Pongpaibul, A.; Angkathunyakul, N.; Chayakulkeeree, M.; Pausawasdi, N.; Charatcharoenwitthaya, P. Performance of Cytomegalovirus Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction Assays of Fecal and Plasma Specimens for Diagnosing Cytomegalovirus Colitis. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2023, 14, e00574.

- Nakase, H.; Matsumura, K.; Yoshino, T.; Chiba, T. Systematic Review: Cytomegalovirus Infection in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 43, 735–740.

- Herfarth, H.H.; Long, M.D.; Rubinas, T.C.; Sandridge, M.; Miller, M.B. Evaluation of a Non-Invasive Method to Detect Cytomegalovirus (CMV)-DNA in Stool Samples of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): A Pilot Study. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2010, 55, 1053–1058.

- Ganzenmueller, T.; Kluba, J.; Becker, J.U.; Bachmann, O.; Heim, A. Detection of Cytomegalovirus (CMV) by Real-Time PCR in Fecal Samples for the Non-Invasive Diagnosis of CMV Intestinal Disease. J. Clin. Virol. 2014, 61, 517–522.

More

Information

Subjects:

Gastroenterology & Hepatology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

747

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

10 Jan 2024

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No