| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Beatrix Zheng | -- | 4838 | 2022-11-25 01:31:00 |

Video Upload Options

Plasma (from grc πλάσμα (plásma) 'moldable substance') is one of the four fundamental states of matter. It contains a significant portion of charged particles – ions and/or electrons. The presence of these charged particles is what primarily sets plasma apart from the other fundamental states of matter. It is the most abundant form of ordinary matter in the universe, being mostly associated with stars, including the Sun. It extends to the rarefied intracluster medium and possibly to intergalactic regions. Plasma can be artificially generated by heating a neutral gas or subjecting it to a strong electromagnetic field. The presence of charged particles makes plasma electrically conductive, with the dynamics of individual particles and macroscopic plasma motion governed by collective electromagnetic fields and very sensitive to externally applied fields. The response of plasma to electromagnetic fields is used in many modern technological devices, such as plasma televisions or plasma etching. Depending on temperature and density, a certain amount of neutral particles may also be present, in which case plasma is called partially ionized. Neon signs and lightning are examples of partially ionized plasmas. Unlike the phase transitions between the other three states of matter, the transition to plasma is not well defined and is a matter of interpretation and context. Whether a given degree of ionization suffices to call a substance 'plasma' depends on the specific phenomenon being considered.

1. Early History

File:Plasma microfields.webm

Plasma was first identified in laboratory by Sir William Crookes. Crookes presented a lecture on what he called "radiant matter" to the British Association for the Advancement of Science, in Sheffield, on Friday, 22 August 1879.[1] Systematic studies of plasma began with the research of Irving Langmuir and his colleagues in the 1920s. Langmuir also introduced the term "plasma" as a description of ionized gas in 1928:[2]

Except near the electrodes, where there are sheaths containing very few electrons, the ionized gas contains ions and electrons in about equal numbers so that the resultant space charge is very small. We shall use the name plasma to describe this region containing balanced charges of ions and electrons.

Lewi Tonks and Harold Mott-Smith, both of whom worked with Langmuir in the 1920s, recall that Langmuir first used the term by analogy with the blood plasma.[3][4] Mott-Smith recalls, in particular, that the transport of electrons from thermionic filaments reminded Langmuir of "the way blood plasma carries red and white corpuscles and germs."[5]

2. Definitions

2.1. The Fourth State of Matter

Plasma is called the fourth state of matter after solid, liquid, and gas.[6][7][8] It is a state of matter in which an ionized substance becomes highly electrically conductive to the point that long-range electric and magnetic fields dominate its behaviour.[9][10]

Plasma is typically an electrically quasineutral medium of unbound positive and negative particles (i.e. the overall charge of a plasma is roughly zero). Although these particles are unbound, they are not "free" in the sense of not experiencing forces. Moving charged particles generate electric currents, and any movement of a charged plasma particle affects and is affected by the fields created by the other charges. In turn this governs collective behaviour with many degrees of variation.[11][12]

Plasma is distinct from the other states of matter. In particular, describing a low-density plasma as merely an "ionized gas" is wrong and misleading, even though it is similar to the gas phase in that both assume no definite shape or volume. The following table summarizes some principal differences:

| Property | Gas | Plasma |

|---|---|---|

| Interactions | Binary: Two-particle collisions are the rule, three-body collisions extremely rare. | Collective: Waves, or organized motion of plasma, are very important because the particles can interact at long ranges through the electric and magnetic forces. |

| Electrical conductivity | Very low: Gases are excellent insulators up to electric field strengths of tens of kilovolts per centimeter.[13] | Very high: For many purposes, the conductivity of a plasma may be treated as infinite. |

| Independently acting species | One: All gas particles behave in a similar way, largely influenced by collisions with one another and by gravity. | Two or more: Electrons and ions possess different charges and vastly different masses, so that they behave differently in many circumstances, with various types of plasma-specific waves and instabilities emerging as a result. |

| Velocity distribution | Maxwellian: Collisions usually lead to a Maxwellian velocity distribution of all gas particles. | Often non-Maxwellian: Collisional interactions are relatively weak in hot plasmas and external forces can drive the plasma far from local equilibrium. |

2.2. Ideal Plasma

Three factors define an ideal plasma:[14][15]

- The plasma approximation: The plasma approximation applies when the plasma parameter Λ,[16] representing the number of charge carriers within the Debye sphere is much higher than unity.[9][10] It can be readily shown that this criterion is equivalent to smallness of the ratio of the plasma electrostatic and thermal energy densities. Such plasmas are called weakly coupled.[17]

- Bulk interactions: The Debye length is much smaller than the physical size of the plasma. This criterion means that interactions in the bulk of the plasma are more important than those at its edges, where boundary effects may take place. When this criterion is satisfied, the plasma is quasineutral.[18]

- Collisionlessness: The electron plasma frequency (measuring plasma oscillations of the electrons) is much larger than the electron–neutral collision frequency. When this condition is valid, electrostatic interactions dominate over the processes of ordinary gas kinetics. Such plasmas are called collisionless.[19]

2.3. Non-Neutral Plasma

The strength and range of the electric force and the good conductivity of plasmas usually ensure that the densities of positive and negative charges in any sizeable region are equal ("quasineutrality"). A plasma with a significant excess of charge density, or, in the extreme case, is composed of a single species, is called a non-neutral plasma. In such a plasma, electric fields play a dominant role. Examples are charged particle beams, an electron cloud in a Penning trap and positron plasmas.[20]

2.4. Dusty Plasma

A dusty plasma contains tiny charged particles of dust (typically found in space). The dust particles acquire high charges and interact with each other. A plasma that contains larger particles is called grain plasma. Under laboratory conditions, dusty plasmas are also called complex plasmas.[21]

3. Properties and Parameters

3.1. Density and Ionization Degree

For plasma to exist, ionization is necessary. The term "plasma density" by itself usually refers to the electron density [math]\displaystyle{ n_e }[/math], that is, the number of charge-contributing electrons per unit volume. The degree of ionization [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha }[/math] is defined as fraction of neutral particles that are ionized:

[math]\displaystyle{ \alpha = \frac{n_i}{n_i + n_n}, }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ n_i }[/math] is the ion density and [math]\displaystyle{ n_n }[/math] the neutral density (in number of particles per unit volume). In the case of fully ionized matter, [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha = 1 }[/math]. Because of the quasineutrality of plasma, the electron and ion densities are related by [math]\displaystyle{ n_e = \langle Z_i\rangle n_i }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ \langle Z_i\rangle }[/math] is the average ion charge (in units of the elementary charge).

3.2. Temperature

Plasma temperature, commonly measured in kelvin or electronvolts, is a measure of the thermal kinetic energy per particle. High temperatures are usually needed to sustain ionization, which is a defining feature of a plasma. The degree of plasma ionization is determined by the electron temperature relative to the ionization energy (and more weakly by the density). In thermal equilibrium, the relationship is given by the Saha equation. At low temperatures, ions and electrons tend to recombine into bound states—atoms[23]—and the plasma will eventually become a gas.

In most cases, the electrons and heavy plasma particles (ions and neutral atoms) separately have a relatively well-defined temperature; that is, their energy distribution function is close to a Maxwellian even in the presence of strong electric or magnetic fields. However, because of the large difference in mass between electrons and ions, their temperatures may be different, sometimes significantly so. This is especially common in weakly ionized technological plasmas, where the ions are often near the ambient temperature while electrons reach thousands of kelvin.[24] The opposite case is the z-pinch plasma where the ion temperature may exceed that of electrons.[25]

3.3. Plasma Potential

Since plasmas are very good electrical conductors, electric potentials play an important role.[clarification needed] The average potential in the space between charged particles, independent of how it can be measured, is called the "plasma potential", or the "space potential". If an electrode is inserted into a plasma, its potential will generally lie considerably below the plasma potential due to what is termed a Debye sheath. The good electrical conductivity of plasmas makes their electric fields very small. This results in the important concept of "quasineutrality", which says the density of negative charges is approximately equal to the density of positive charges over large volumes of the plasma ([math]\displaystyle{ n_e = \langle Z\rangle n_i }[/math]), but on the scale of the Debye length, there can be charge imbalance. In the special case that double layers are formed, the charge separation can extend some tens of Debye lengths.[27]

The magnitude of the potentials and electric fields must be determined by means other than simply finding the net charge density. A common example is to assume that the electrons satisfy the Boltzmann relation: [math]\displaystyle{ n_e \propto e^{e\Phi/k_BT_e}. }[/math]

Differentiating this relation provides a means to calculate the electric field from the density: [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{E} = (k_BT_e/e)(\nabla n_e/n_e). }[/math]

It is possible to produce a plasma that is not quasineutral. An electron beam, for example, has only negative charges. The density of a non-neutral plasma must generally be very low, or it must be very small, otherwise, it will be dissipated by the repulsive electrostatic force.[28]

3.4. Magnetization

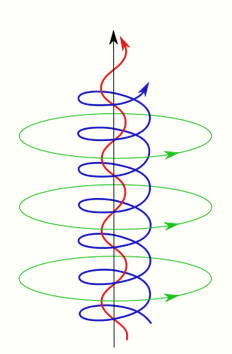

The existence of charged particles causes the plasma to generate, and be affected by, magnetic fields. Plasma with a magnetic field strong enough to influence the motion of the charged particles is said to be magnetized. A common quantitative criterion is that a particle on average completes at least one gyration around the magnetic-field line before making a collision, i.e., [math]\displaystyle{ \nu_{\mathrm{ce}} / \nu_{\mathrm{coll}} \gt 1 }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ \nu_{\mathrm{ce}} }[/math] is the electron gyrofrequency and [math]\displaystyle{ \nu_{\mathrm{coll}} }[/math] is the electron collision rate. It is often the case that the electrons are magnetized while the ions are not. Magnetized plasmas are anisotropic, meaning that their properties in the direction parallel to the magnetic field are different from those perpendicular to it. While electric fields in plasmas are usually small due to the plasma high conductivity, the electric field associated with a plasma moving with velocity [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{v} }[/math] in the magnetic field [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{B} }[/math] is given by the usual Lorentz formula [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E} = -\mathbf{v}\times\mathbf{B} }[/math], and is not affected by Debye shielding.[29]

4. Mathematical Descriptions

To completely describe the state of a plasma, all of the particle locations and velocities that describe the electromagnetic field in the plasma region would need to be written down. However, it is generally not practical or necessary to keep track of all the particles in a plasma. Therefore, plasma physicists commonly use less detailed descriptions, of which there are two main types:

4.1. Fluid Model

Fluid models describe plasmas in terms of smoothed quantities, like density and averaged velocity around each position (see Plasma parameters). One simple fluid model, magnetohydrodynamics, treats the plasma as a single fluid governed by a combination of Maxwell's equations and the Navier–Stokes equations. A more general description is the two-fluid plasma,[31] where the ions and electrons are described separately. Fluid models are often accurate when collisionality is sufficiently high to keep the plasma velocity distribution close to a Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution. Because fluid models usually describe the plasma in terms of a single flow at a certain temperature at each spatial location, they can neither capture velocity space structures like beams or double layers, nor resolve wave-particle effects.

4.2. Kinetic Model

Kinetic models describe the particle velocity distribution function at each point in the plasma and therefore do not need to assume a Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution. A kinetic description is often necessary for collisionless plasmas. There are two common approaches to kinetic description of a plasma. One is based on representing the smoothed distribution function on a grid in velocity and position. The other, known as the particle-in-cell (PIC) technique, includes kinetic information by following the trajectories of a large number of individual particles. Kinetic models are generally more computationally intensive than fluid models. The Vlasov equation may be used to describe the dynamics of a system of charged particles interacting with an electromagnetic field. In magnetized plasmas, a gyrokinetic approach can substantially reduce the computational expense of a fully kinetic simulation.

5. Plasma Science and Technology

Plasmas are the object of study of the academic field of plasma science or plasma physics,[32] including sub-disciplines such as space plasma physics. It currently involves the following fields of active research and features across many journals, whose interest includes:

|

|

Plasmas can appear in nature in various forms and locations, summarised in the following table:

| Artificially produced | Terrestrial plasmas | Space and astrophysical plasmas |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

5.1. Space and Astrophysics

Plasmas are by far the most common phase of ordinary matter in the universe, both by mass and by volume.[38]

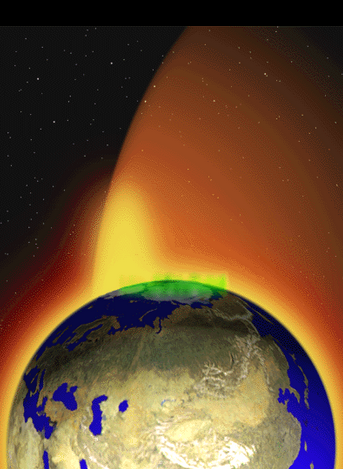

Above the Earth's surface, the ionosphere is a plasma,[39] and the magnetosphere contains plasma.[40] Within our Solar System, interplanetary space is filled with the plasma expelled via the solar wind, extending from the Sun's surface out to the heliopause. Furthermore, all the distant stars, and much of interstellar space or intergalactic space is also likely filled with plasma, albeit at very low densities. Astrophysical plasmas are also observed in accretion disks around stars or compact objects like white dwarfs, neutron stars, or black holes in close binary star systems.[41] Plasma is associated with ejection of material in astrophysical jets, which have been observed with accreting black holes[42] or in active galaxies like M87's jet that possibly extends out to 5,000 light-years.[43]

5.2. Artificial Plasmas

Most artificial plasmas are generated by the application of electric and/or magnetic fields through a gas. Plasma generated in a laboratory setting and for industrial use can be generally categorized by:

- The type of power source used to generate the plasma—DC, AC (typically with radio frequency (RF)) and microwave

- The pressure they operate at—vacuum pressure (< 10 mTorr or 1 Pa), moderate pressure (≈1 Torr or 100 Pa), atmospheric pressure (760 Torr or 100 kPa)

- The degree of ionization within the plasma—fully, partially, or weakly ionized

- The temperature relationships within the plasma—thermal plasma ([math]\displaystyle{ T_e = T_i = T_{gas} }[/math]), non-thermal or "cold" plasma ([math]\displaystyle{ T_e \gg T_i = T_{gas} }[/math])

- The electrode configuration used to generate the plasma

- The magnetization of the particles within the plasma—magnetized (both ion and electrons are trapped in Larmor orbits by the magnetic field), partially magnetized (the electrons but not the ions are trapped by the magnetic field), non-magnetized (the magnetic field is too weak to trap the particles in orbits but may generate Lorentz forces)

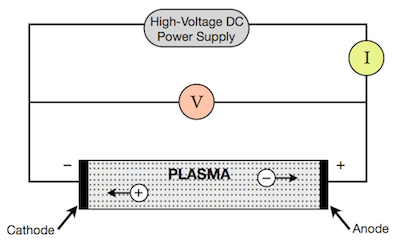

Generation of artificial plasma

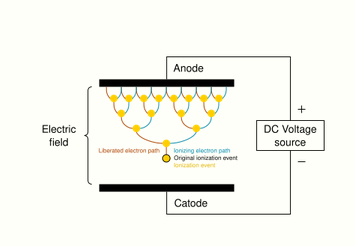

Just like the many uses of plasma, there are several means for its generation. However, one principle is common to all of them: there must be energy input to produce and sustain it.[44] For this case, plasma is generated when an electric current is applied across a dielectric gas or fluid (an electrically non-conducting material) as can be seen in the adjacent image, which shows a discharge tube as a simple example (DC used for simplicity).

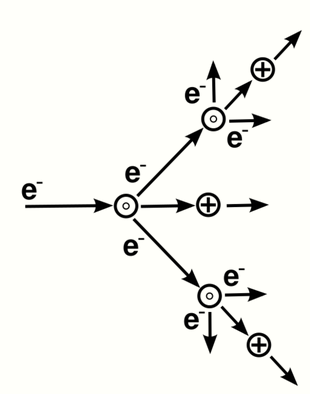

The potential difference and subsequent electric field pull the bound electrons (negative) toward the anode (positive electrode) while the cathode (negative electrode) pulls the nucleus.[45] As the voltage increases, the current stresses the material (by electric polarization) beyond its dielectric limit (termed strength) into a stage of electrical breakdown, marked by an electric spark, where the material transforms from being an insulator into a conductor (as it becomes increasingly ionized). The underlying process is the Townsend avalanche, where collisions between electrons and neutral gas atoms create more ions and electrons (as can be seen in the figure on the right). The first impact of an electron on an atom results in one ion and two electrons. Therefore, the number of charged particles increases rapidly (in the millions) only "after about 20 successive sets of collisions",[46] mainly due to a small mean free path (average distance travelled between collisions).

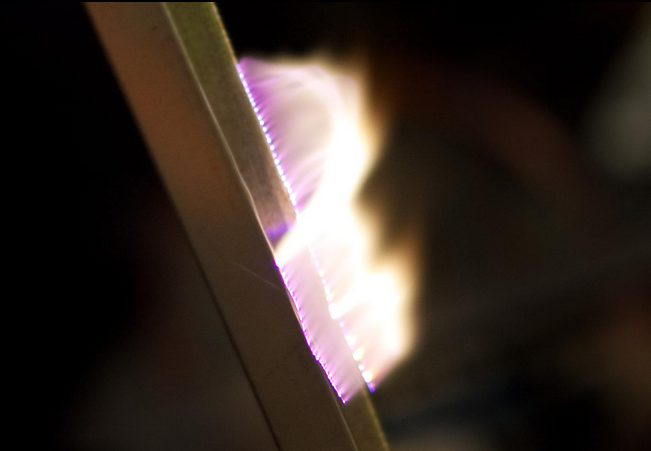

Electric arc

With ample current density and ionization, this forms a luminous electric arc (a continuous electric discharge similar to lightning) between the electrodes.[47] Electrical resistance along the continuous electric arc creates heat, which dissociates more gas molecules and ionizes the resulting atoms (where degree of ionization is determined by temperature), and as per the sequence: solid-liquid-gas-plasma, the gas is gradually turned into a thermal plasma.[48] A thermal plasma is in thermal equilibrium, which is to say that the temperature is relatively homogeneous throughout the heavy particles (i.e. atoms, molecules and ions) and electrons. This is so because when thermal plasmas are generated, electrical energy is given to electrons, which, due to their great mobility and large numbers, are able to disperse it rapidly and by elastic collision (without energy loss) to the heavy particles.[49][50]

Examples of industrial/commercial plasma

Because of their sizable temperature and density ranges, plasmas find applications in many fields of research, technology and industry. For example, in: industrial and extractive metallurgy,[49][51] surface treatments such as plasma spraying (coating), etching in microelectronics,[52] metal cutting[53] and welding; as well as in everyday vehicle exhaust cleanup and fluorescent/luminescent lamps,[44] fuel ignition, while even playing a part in supersonic combustion engines for aerospace engineering.[54]

Low-pressure discharges

- Glow discharge plasmas: non-thermal plasmas generated by the application of DC or low frequency RF (<100 kHz) electric field to the gap between two metal electrodes. Probably the most common plasma; this is the type of plasma generated within fluorescent light tubes.[55]

- Capacitively coupled plasma (CCP): similar to glow discharge plasmas, but generated with high frequency RF electric fields, typically 13.56 MHz. These differ from glow discharges in that the sheaths are much less intense. These are widely used in the microfabrication and integrated circuit manufacturing industries for plasma etching and plasma enhanced chemical vapor deposition.[56]

- Cascaded arc plasma source: a device to produce low temperature (≈1eV) high density plasmas (HDP).

- Inductively coupled plasma (ICP): similar to a CCP and with similar applications but the electrode consists of a coil wrapped around the chamber where plasma is formed.[57]

- Wave heated plasma: similar to CCP and ICP in that it is typically RF (or microwave). Examples include helicon discharge and electron cyclotron resonance (ECR).[58]

Atmospheric pressure

- Arc discharge: this is a high power thermal discharge of very high temperature (≈10,000 K). It can be generated using various power supplies. It is commonly used in metallurgical processes. For example, it is used to smelt minerals containing Al2O3 to produce aluminium.

- Corona discharge: this is a non-thermal discharge generated by the application of high voltage to sharp electrode tips. It is commonly used in ozone generators and particle precipitators.

- Dielectric barrier discharge (DBD): this is a non-thermal discharge generated by the application of high voltages across small gaps wherein a non-conducting coating prevents the transition of the plasma discharge into an arc. It is often mislabeled 'Corona' discharge in industry and has similar application to corona discharges. A common usage of this discharge is in a plasma actuator for vehicle drag reduction.[59] It is also widely used in the web treatment of fabrics.[60] The application of the discharge to synthetic fabrics and plastics functionalizes the surface and allows for paints, glues and similar materials to adhere.[61] The dielectric barrier discharge was used in the mid-1990s to show that low temperature atmospheric pressure plasma is effective in inactivating bacterial cells.[62] This work and later experiments using mammalian cells led to the establishment of a new field of research known as plasma medicine. The dielectric barrier discharge configuration was also used in the design of low temperature plasma jets. These plasma jets are produced by fast propagating guided ionization waves known as plasma bullets.[63]

- Capacitive discharge: this is a nonthermal plasma generated by the application of RF power (e.g., 13.56 MHz) to one powered electrode, with a grounded electrode held at a small separation distance on the order of 1 cm. Such discharges are commonly stabilized using a noble gas such as helium or argon.[64]

- "Piezoelectric direct discharge plasma:" is a nonthermal plasma generated at the high-side of a piezoelectric transformer (PT). This generation variant is particularly suited for high efficient and compact devices where a separate high voltage power supply is not desired.

MHD converters

A world effort was triggered in the 1960s to study magnetohydrodynamic converters in order to bring MHD power conversion to market with commercial power plants of a new kind, converting the kinetic energy of a high velocity plasma into electricity with no moving parts at a high efficiency. Research was also conducted in the field of supersonic and hypersonic aerodynamics to study plasma interaction with magnetic fields to eventually achieve passive and even active flow control around vehicles or projectiles, in order to soften and mitigate shock waves, lower thermal transfer and reduce drag.

Such ionized gases used in "plasma technology" ("technological" or "engineered" plasmas) are usually weakly ionized gases in the sense that only a tiny fraction of the gas molecules are ionized.[65] These kinds of weakly ionized gases are also nonthermal "cold" plasmas. In the presence of magnetics fields, the study of such magnetized nonthermal weakly ionized gases involves resistive magnetohydrodynamics with low magnetic Reynolds number, a challenging field of plasma physics where calculations require dyadic tensors in a 7-dimensional phase space. When used in combination with a high Hall parameter, a critical value triggers the problematic electrothermal instability which limited these technological developments.

6. Complex Plasma Phenomena

Although the underlying equations governing plasmas are relatively simple, plasma behaviour is extraordinarily varied and subtle: the emergence of unexpected behaviour from a simple model is a typical feature of a complex system. Such systems lie in some sense on the boundary between ordered and disordered behaviour and cannot typically be described either by simple, smooth, mathematical functions, or by pure randomness. The spontaneous formation of interesting spatial features on a wide range of length scales is one manifestation of plasma complexity. The features are interesting, for example, because they are very sharp, spatially intermittent (the distance between features is much larger than the features themselves), or have a fractal form. Many of these features were first studied in the laboratory, and have subsequently been recognized throughout the universe. Examples of complexity and complex structures in plasmas include:

6.1. Filamentation

Striations or string-like structures,[66] also known as Birkeland currents, are seen in many plasmas, like the plasma ball, the aurora,[67] lightning,[68] electric arcs, solar flares,[69] and supernova remnants.[70] They are sometimes associated with larger current densities, and the interaction with the magnetic field can form a magnetic rope structure.[71] (See also Plasma pinch)

Filamentation also refers to the self-focusing of a high power laser pulse. At high powers, the nonlinear part of the index of refraction becomes important and causes a higher index of refraction in the center of the laser beam, where the laser is brighter than at the edges, causing a feedback that focuses the laser even more. The tighter focused laser has a higher peak brightness (irradiance) that forms a plasma. The plasma has an index of refraction lower than one, and causes a defocusing of the laser beam. The interplay of the focusing index of refraction, and the defocusing plasma makes the formation of a long filament of plasma that can be micrometers to kilometers in length.[72] One interesting aspect of the filamentation generated plasma is the relatively low ion density due to defocusing effects of the ionized electrons.[73] (See also Filament propagation)

6.2. Impermeable Plasma

Impermeable plasma is a type of thermal plasma which acts like an impermeable solid with respect to gas or cold plasma and can be physically pushed. Interaction of cold gas and thermal plasma was briefly studied by a group led by Hannes Alfvén in 1960s and 1970s for its possible applications in insulation of fusion plasma from the reactor walls.[74] However, later it was found that the external magnetic fields in this configuration could induce kink instabilities in the plasma and subsequently lead to an unexpectedly high heat loss to the walls.[75] In 2013, a group of materials scientists reported that they have successfully generated stable impermeable plasma with no magnetic confinement using only an ultrahigh-pressure blanket of cold gas. While spectroscopic data on the characteristics of plasma were claimed to be difficult to obtain due to the high pressure, the passive effect of plasma on synthesis of different nanostructures clearly suggested the effective confinement. They also showed that upon maintaining the impermeability for a few tens of seconds, screening of ions at the plasma-gas interface could give rise to a strong secondary mode of heating (known as viscous heating) leading to different kinetics of reactions and formation of complex nanomaterials.[76]

References

- "Find in a Library: On radiant matter a lecture delivered to the British Association for the Advancement of Science, at Sheffield, Friday, August 22, 1879". http://www.worldcatlibraries.org/wcpa/top3mset/5dcb9349d366f8ec.html. "Radiant Matter". http://www.tfcbooks.com/mall/more/315rm.htm.

- Langmuir, I. (1928). "Oscillations in Ionized Gases". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 14 (8): 627–637. doi:10.1073/pnas.14.8.627. PMID 16587379. Bibcode: 1928PNAS...14..627L. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1085653

- Tonks, Lewi (1967). "The birth of "plasma"". American Journal of Physics 35 (9): 857–858. doi:10.1119/1.1974266. Bibcode: 1967AmJPh..35..857T. https://dx.doi.org/10.1119%2F1.1974266

- Brown, Sanborn C. (1978). "Chapter 1: A Short History of Gaseous Electronics". Gaseous Electronics. 1. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-349701-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=C1UmeQ_E0_AC&pg=PA1.

- Mott-Smith, Harold M. (1971). "History of "plasmas"". Nature 233 (5316): 219. doi:10.1038/233219a0. PMID 16063290. Bibcode: 1971Natur.233..219M. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2F233219a0

- Frank-Kamenetskii, David A. (1972) (in en). Plasma-The Fourth State of Matter (3rd ed.). New York: Plenum Press. ISBN 9781468418965. https://books.google.com/books?id=Q_vpBwAAQBAJ&q=%22Plasma-The+Fourth+State+of+Matter%22+Frank-Kamenetskii.

- Yaffa Eliezer, Shalom Eliezer, The Fourth State of Matter: An Introduction to the Physics of Plasma, Publisher: Adam Hilger, 1989, ISBN:978-0-85274-164-1, 226 pages, page 5

- Bittencourt, J.A. (2004). Fundamentals of Plasma Physics. Springer. p. 1. ISBN 9780387209753. https://books.google.com/books?id=qCA64ys-5bUC&pg=PA1.

- Chen, Francis F. (1984). Introduction to Plasma Physics and controlled fusion. Springer International Publishing. pp. 2–3. ISBN 9781475755954. https://books.google.com/books?id=WGbaBwAAQBAJ&q=editions:9PGss7GnX-MC.

- Freidberg, Jeffrey P. (2008). Plasma Physics and Fusion Energy. Cambridge University Press. p. 121. ISBN 9781139462150. https://books.google.com/books?id=Vyoe88GEVz4C.

- Sturrock, Peter A. (1994). Plasma Physics: An Introduction to the Theory of Astrophysical, Geophysical & Laboratory Plasmas. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-44810-9.

- Hazeltine, R.D.; Waelbroeck, F.L. (2004). The Framework of Plasma Physics. Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-7382-0047-7.

- Hong, Alice (2000). "Dielectric Strength of Air". in Elert, Glenn. https://hypertextbook.com/facts/2000/AliceHong.shtml.

- Dendy, R. O. (1990). Plasma Dynamics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-852041-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=puuQM4Dx0zYC&q=plasma+dynamics+dendy&pg=PR19.

- Hastings, Daniel; Garrett, Henry (2000). Spacecraft-Environment Interactions. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47128-2.

- Chen, Francis F. (1984). Introduction to plasma physics and controlled fusion. Chen, Francis F., 1929- (2nd ed.). New York: Plenum Press. ISBN 978-0306413322. OCLC 9852700. https://books.google.com/books?id=WGbaBwAAQBAJ&q=editions:9PGss7GnX-MC.

- Fortov, Vladimir E; Iakubov, Igor T (November 1999). The Physics of Non-Ideal Plasma. WORLD SCIENTIFIC. doi:10.1142/3634. Template:Isbnt. ISBN 978-981-02-3305-1. http://www.worldscientific.com/worldscibooks/10.1142/3634. Retrieved 2021-03-19.

- "Quasi-neutrality - The Plasma Universe theory (Wikipedia-like Encyclopedia)" (in en). http://www.plasma-universe.com/Quasi-neutrality.

- Klimontovich, Yu L. (1997-01-31). "Physics of collisionless plasma". Physics-Uspekhi 40 (1): 21–51. doi:10.1070/PU1997v040n01ABEH000200. ISSN 1063-7869. http://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1070/PU1997v040n01ABEH000200/meta. Retrieved 2021-03-19.

- Greaves, R. G.; Tinkle, M. D.; Surko, C. M. (1994). "Creation and uses of positron plasmas". Physics of Plasmas 1 (5): 1439. doi:10.1063/1.870693. Bibcode: 1994PhPl....1.1439G. https://dx.doi.org/10.1063%2F1.870693

- Morfill, G. E.; Ivlev, Alexei V. (2009). "Complex plasmas: An interdisciplinary research field". Reviews of Modern Physics 81 (4): 1353–1404. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.81.1353. Bibcode: 2009RvMP...81.1353M. https://dx.doi.org/10.1103%2FRevModPhys.81.1353

- Plasma fountain Source , press release: Solar Wind Squeezes Some of Earth's Atmosphere into Space http://pwg.gsfc.nasa.gov/istp/news/9812/solar1.html

- Nicholson, Dwight R. (1983). Introduction to Plasma Theory. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-09045-8.

- Hamrang, Abbas (2014). Advanced Non-Classical Materials with Complex Behavior: Modeling and Applications, Volume 1. CRC Press. pp. 10.

- Maron, Yitzhak (2020-06-01). "Experimental determination of the thermal, turbulent, and rotational ion motion and magnetic field profiles in imploding plasmas". Physics of Plasmas 27 (6): 060901. doi:10.1063/5.0009432. ISSN 1070-664X. Bibcode: 2020PhPl...27f0901M. https://dx.doi.org/10.1063%2F5.0009432

- See Flashes in the Sky: Earth's Gamma-Ray Bursts Triggered by Lightning http://www.nasa.gov/vision/universe/solarsystem/rhessi_tgf.html

- Block, Lars P. (1978). "A double layer review". Astrophysics and Space Science 55 (1): 59–83. doi:10.1007/BF00642580. ISSN 1572-946X. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00642580. Retrieved 2021-07-15.

- Plasma science : from fundamental research to technological applications. National Research Council (U.S.). Panel on Opportunities in Plasma Science and Technology.. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. 1995. pp. 51. ISBN 9780309052313. OCLC 42854229. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/42854229

- Richard Fitzpatrick, Introduction to Plasma Physics, Magnetized plasmas http://farside.ph.utexas.edu/teaching/plasma/lectures/node10.html

- See Evolution of the Solar System , 1976 https://history.nasa.gov/SP-345/ch15.htm#250

- Roy, Subrata; Pandey, B. P. (September 2002). "Numerical investigation of a Hall thruster plasma". Physics of Plasmas 9 (9): 4052–4060. doi:10.1063/1.1498261. Bibcode: 2002PhPl....9.4052R. https://dx.doi.org/10.1063%2F1.1498261

- "Plasma Physics". 4 May 2016. https://www.colorado.edu/physics/research/plasma-physics.

- "Wrangling flow to quiet cars and aircraft," EurekAlert, http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2013-10/aiop-wft101813.php, viewed on 1/20/2014.

- Shiraishi, Taisuke (2009). "A Study of Volumetric Ignition Using High-Speed Plasma for Improving Lean Combustion Performance in Internal Combustion Engines". SAE International Journal of Engines (SAE International) 1 (1): 399–408. doi:10.4271/2008-01-0466. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26308290. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- "High-tech dentistry – "St Elmo's frier" – Using a plasma torch to clean your teeth". The Economist print edition. Jun 17, 2009. http://www.economist.com/displaystory.cfm?story_id=13794903&fsrc=rss.

- IPPEX Glossary of Fusion Terms . Ippex.pppl.gov. Retrieved on 2011-11-19. http://ippex.pppl.gov/fusion/glossary.html

- Helmenstine, Anne Marie. "What is the State of Matter of Fire or Flame? Is it a Liquid, Solid, or Gas?". About.com. http://chemistry.about.com/od/chemistryfaqs/f/firechemistry.htm.

- It is assumed that more than 99% the visible universe is made of some form of plasma.Gurnett, D. A.; Bhattacharjee, A. (2005). Introduction to Plasma Physics: With Space and Laboratory Applications. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-521-36483-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=VcueZlunrbcC&pg=PA2. Scherer, K; Fichtner, H; Heber, B (2005). Space Weather: The Physics Behind a Slogan. Berlin: Springer. p. 138. ISBN 978-3-540-22907-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=irHgIUtLi0gC&pg=PA138. .

- Kelley, M. C. (2009). The Earth's Ionosphere: Plasma Physics and Electrodynamics (2nd ed.). Academic Press. ISBN 9780120884254.

- Russell, C.T. (1990). "The Magnetopause". Physics of Magnetic Flux Ropes. Geophysical Monograph Series 58: 439–453. doi:10.1029/GM058p0439. ISBN 0-87590-026-7. Bibcode: 1990GMS....58..439R. http://www-ssc.igpp.ucla.edu/ssc/tutorial/magnetopause.html. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- Mészáros, Péter (2010) The High Energy Universe: Ultra-High Energy Events in Astrophysics and Cosmology, Publisher: Cambridge University Press, ISBN:978-0-521-51700-3, p. 99 . https://books.google.com/books?id=NXvE_zQX5kAC&lpg=PA99&dq=%22Black%20hole%22%20plasma%20acreting&pg=PA99

- Raine, Derek J. and Thomas, Edwin George (2010) Black Holes: An Introduction, Publisher: Imperial College Press, ISBN:978-1-84816-382-9, p. 160 https://books.google.com/books?id=O3puAMw5U3UC&lpg=PA160

- Nemiroff, Robert and Bonnell, Jerry (11 December 2004) Astronomy Picture of the Day , nasa.gov http://apod.nasa.gov/apod/ap041211.html

- Hippler, R., ed (2008). "Plasma Sources". Low Temperature Plasmas: Fundamentals, Technologies, and Techniques (2nd ed.). Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-40673-9.

- Chen, Francis F. (1984). Plasma Physics and Controlled Fusion. Plenum Press. ISBN 978-0-306-41332-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=WGbaBwAAQBAJ&q=editions:9PGss7GnX-MC.

- Leal-Quirós, Edbertho (2004). "Plasma Processing of Municipal Solid Waste". Brazilian Journal of Physics 34 (4B): 1587–1593. doi:10.1590/S0103-97332004000800015. Bibcode: 2004BrJPh..34.1587L. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590%2FS0103-97332004000800015

- The material undergoes various "regimes" or stages (e.g. saturation, breakdown, glow, transition and thermal arc) as the voltage is increased under the voltage-current relationship. The voltage rises to its maximum value in the saturation stage, and thereafter it undergoes fluctuations of the various stages; while the current progressively increases throughout.[56]

- Across literature, there appears to be no strict definition on where the boundary is between a gas and plasma. Nevertheless, it is enough to say that at 2,000°C the gas molecules become atomized, and ionized at 3,000 °C and "in this state, [the] gas has a liquid like viscosity at atmospheric pressure and the free electric charges confer relatively high electrical conductivities that can approach those of metals."[57]

- Gomez, E.; Rani, D. A.; Cheeseman, C. R.; Deegan, D.; Wise, M.; Boccaccini, A. R. (2009). "Thermal plasma technology for the treatment of wastes: A critical review". Journal of Hazardous Materials 161 (2–3): 614–626. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.04.017. PMID 18499345. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.jhazmat.2008.04.017

- Note that non-thermal, or non-equilibrium plasmas are not as ionized and have lower energy densities, and thus the temperature is not dispersed evenly among the particles, where some heavy ones remain "cold".

- Szałatkiewicz, J. (2016). "Metals Recovery from Artificial Ore in Case of Printed Circuit Boards, Using Plasmatron Plasma Reactor". Materials 9 (8): 683–696. doi:10.3390/ma9080683. PMID 28773804. Bibcode: 2016Mate....9..683S. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5512349

- National Research Council (1991). Plasma Processing of Materials : Scientific Opportunities and Technological Challenges. National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-04597-1.

- Nemchinsky, V. A.; Severance, W. S. (2006). "What we know and what we do not know about plasma arc cutting". Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics 39 (22): R423. doi:10.1088/0022-3727/39/22/R01. Bibcode: 2006JPhD...39R.423N. https://dx.doi.org/10.1088%2F0022-3727%2F39%2F22%2FR01

- Peretich, M.A.; O'Brien, W.F.; Schetz, J.A. (2007). Plasma torch power control for scramjet application. Virginia Space Grant Consortium. http://www.vsgc.odu.edu/src/SRC07/SRC07papers/Mark%20Peretich%20_%20PaperFinal%20Report.pdf. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- Stern, David P.. "The Fluorescent Lamp: A plasma you can use". http://www-spof.gsfc.nasa.gov/Education/wfluor.html.

- Sobolewski, M.A.; Langan & Felker, J.G. & B.S. (1997). "Electrical optimization of plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition chamber cleaning plasmas". Journal of Vacuum Science and Technology B 16 (1): 173–182. doi:10.1116/1.589774. Bibcode: 1998JVSTB..16..173S. http://physics.nist.gov/MajResProj/rfcell/Publications/MAS_JVSTB16_1.pdf.

- Okumura, T. (2010). "Inductively Coupled Plasma Sources and Applications". Physics Research International 2010: 1–14. doi:10.1155/2010/164249. https://dx.doi.org/10.1155%2F2010%2F164249

- Plasma Chemistry. Cambridge University Press. 2008. p. 229. ISBN 9781139471732. https://books.google.com/books?id=ZzmtGEHCC9MC&pg=PA229.

- Roy, S.; Zhao, P.; Dasgupta, A.; Soni, J. (2016). "Dielectric barrier discharge actuator for vehicle drag reduction at highway speeds". AIP Advances 6 (2): 025322. doi:10.1063/1.4942979. Bibcode: 2016AIPA....6b5322R. https://dx.doi.org/10.1063%2F1.4942979

- Leroux, F.; Perwuelz, A.; Campagne, C.; Behary, N. (2006). "Atmospheric air-plasma treatments of polyester textile structures". Journal of Adhesion Science and Technology 20 (9): 939–957. doi:10.1163/156856106777657788. https://dx.doi.org/10.1163%2F156856106777657788

- Leroux, F. D. R.; Campagne, C.; Perwuelz, A.; Gengembre, L. O. (2008). "Polypropylene film chemical and physical modifications by dielectric barrier discharge plasma treatment at atmospheric pressure". Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 328 (2): 412–420. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2008.09.062. PMID 18930244. Bibcode: 2008JCIS..328..412L. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.jcis.2008.09.062

- Laroussi, M. (1996). "Sterilization of contaminated matter with an atmospheric pressure plasma". IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science 24 (3): 1188–1191. doi:10.1109/27.533129. Bibcode: 1996ITPS...24.1188L. https://dx.doi.org/10.1109%2F27.533129

- Lu, X.; Naidis, G.V.; Laroussi, M.; Ostrikov, K. (2014). "Guided ionization waves: Theory and experiments". Physics Reports 540 (3): 123. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2014.02.006. Bibcode: 2014PhR...540..123L. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.physrep.2014.02.006

- Park, J.; Henins, I.; Herrmann, H. W.; Selwyn, G. S.; Hicks, R. F. (2001). "Discharge phenomena of an atmospheric pressure radio-frequency capacitive plasma source". Journal of Applied Physics 89 (1): 20. doi:10.1063/1.1323753. Bibcode: 2001JAP....89...20P. https://zenodo.org/record/1231852.

- Plasma scattering of electromagnetic radiation : theory and measurement techniques. Froula, Dustin H. (1st ed., 2nd ed.). Burlington, MA: Academic Press/Elsevier. 2011. pp. 273. ISBN 978-0080952031. OCLC 690642377. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/690642377

- Dickel, J. R. (1990). "The Filaments in Supernova Remnants: Sheets, Strings, Ribbons, or?". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society 22: 832. Bibcode: 1990BAAS...22..832D. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1990BAAS...22..832D

- Grydeland, T. (2003). "Interferometric observations of filamentary structures associated with plasma instability in the auroral ionosphere". Geophysical Research Letters 30 (6): 1338. doi:10.1029/2002GL016362. Bibcode: 2003GeoRL..30.1338G. https://dx.doi.org/10.1029%2F2002GL016362

- Moss, G. D.; Pasko, V. P.; Liu, N.; Veronis, G. (2006). "Monte Carlo model for analysis of thermal runaway electrons in streamer tips in transient luminous events and streamer zones of lightning leaders". Journal of Geophysical Research 111 (A2): A02307. doi:10.1029/2005JA011350. Bibcode: 2006JGRA..111.2307M. https://dx.doi.org/10.1029%2F2005JA011350

- Doherty, Lowell R.; Menzel, Donald H. (1965). "Filamentary Structure in Solar Prominences". The Astrophysical Journal 141: 251. doi:10.1086/148107. Bibcode: 1965ApJ...141..251D. https://dx.doi.org/10.1086%2F148107

- "Hubble views the Crab Nebula M1: The Crab Nebula Filaments". http://seds.lpl.arizona.edu/messier/more/m001_hst.html. . The University of Arizona

- Zhang, Y. A.; Song, M. T.; Ji, H. S. (2002). "A rope-shaped solar filament and a IIIb flare". Chinese Astronomy and Astrophysics 26 (4): 442–450. doi:10.1016/S0275-1062(02)00095-4. Bibcode: 2002ChA&A..26..442Z. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS0275-1062%2802%2900095-4

- Chin, S. L. (2006). "Some Fundamental Concepts of Femtosecond Laser Filamentation". Progress in Ultrafast Intense Laser Science III. Springer Series in Chemical Physics. 49. 281. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-73794-0_12. ISBN 978-3-540-73793-3. Bibcode: 2008pui3.book..243C. http://icpr.snu.ac.kr/resource/wop.pdf/J01/2006/049/S01/J012006049S010281.pdf.

- Talebpour, A.; Abdel-Fattah, M.; Chin, S. L. (2000). "Focusing limits of intense ultrafast laser pulses in a high pressure gas: Road to new spectroscopic source". Optics Communications 183 (5–6): 479–484. doi:10.1016/S0030-4018(00)00903-2. Bibcode: 2000OptCo.183..479T. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS0030-4018%2800%2900903-2

- Alfvén, H.; Smårs, E. (1960). "Gas-Insulation of a Hot Plasma". Nature 188 (4753): 801–802. doi:10.1038/188801a0. Bibcode: 1960Natur.188..801A. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2F188801a0

- Braams, C.M. (1966). "Stability of Plasma Confined by a Cold-Gas Blanket". Physical Review Letters 17 (9): 470–471. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.17.470. Bibcode: 1966PhRvL..17..470B. https://dx.doi.org/10.1103%2FPhysRevLett.17.470

- Yaghoubi, A.; Mélinon, P. (2013). "Tunable synthesis and in situ growth of silicon-carbon mesostructures using impermeable plasma". Scientific Reports 3: 1083. doi:10.1038/srep01083. PMID 23330064. Bibcode: 2013NatSR...3E1083Y. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3547321