Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | David M. Bastidas | + 1428 word(s) | 1428 | 2021-10-29 10:45:25 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | + 439 word(s) | 1867 | 2021-11-22 04:12:16 | | | | |

| 3 | Lindsay Dong | Meta information modification | 1867 | 2022-03-28 06:02:15 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Bastidas, D.M. Effect of Phosphate on Steel Reinforcements in Mortar. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/16161 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Bastidas DM. Effect of Phosphate on Steel Reinforcements in Mortar. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/16161. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Bastidas, David M.. "Effect of Phosphate on Steel Reinforcements in Mortar" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/16161 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Bastidas, D.M. (2021, November 18). Effect of Phosphate on Steel Reinforcements in Mortar. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/16161

Bastidas, David M.. "Effect of Phosphate on Steel Reinforcements in Mortar." Encyclopedia. Web. 18 November, 2021.

Copy Citation

Sodium nitrite (NaNO2), disodium stannate (Na2SnO3), disodium molybdate (Na2MoO4), sodium borates (NaBO2), trisodium borate (Na3BO3), cerium nitrate (Ce(NO3)2) and trisodium phosphate (Na3PO4) (TSP) have been used as corrosion inhibitors for steel. The use of phosphate chemical conversion (PCC) coatings causes the phosphates to react with Fe ions, forming insoluble compounds, thus impeding the corrosion process. Soluble phosphates react with portlandite to trigger the precipitation of an insoluble phosphate, thus reducing the phosphate content in the pore solution and, consequently, acting as a corrosion prevention method.

steel reinforcements

phosphate

corrosion

inhibition efficiency

1. Introduction

Due to its comparatively low cost and versatility, reinforced concrete is commonly used in the construction industry [1][2][3][4][5][6]. Despite its excellent compressive force, concrete alone is unable to withstand the necessary tensile load and reinforcements are necessary. The combined properties of concrete and steel reinforcements provide high compression strength as well as increased mechanical properties, thus making it an ideal composite material for a multitude of applications and structures [2]. The corrosion of these steel reinforcements is considered to be the greatest threat to the integrity of these structures and their service life [3][4]. Various solutions have been implemented to deter corrosion, such as corrosion inhibitors and many others [6][7][8][9][10].

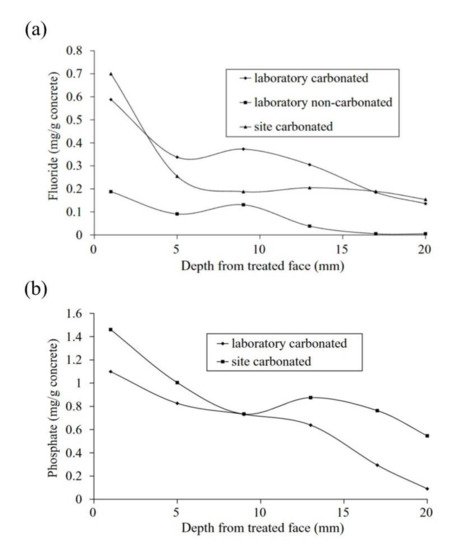

Corrosion inhibitors for steel in concrete can be used by addition to the cement paste, called admixed corrosion inhibitor (ACI) [11][12], or by applying with brush or spray to the hardened concrete surface diffusing through the pores of the concrete, known as migrating corrosion inhibitor (MCI), see Figure 1 [13][14][15].

Figure 1. Penetration depth of inhibitors acting as migrating corrosion inhibitors (MCI): (a) water-soluble fluoride and (b) water-soluble phosphate [15]. Reproduced with permission from Ngala, V. et al., Corros. Sci.; published by Elsevier, 2003.

2. Effect of Phosphate on Steel Reinforcements in Mortar

The corrosion-inhibition mechanism of phosphates is not fully understood, it is believed that phosphate inhibitors react with the iron ions generated in the corrosion process [16], or with ions present in the mortar, such as calcium, which forms calcium phosphate (Ca3(PO4)2) precipitates, filling the pores and cracks of the mortar, thus impeding the diffusion of aggressive ions [17][18][19][20][21]. It has been found that sodium phosphate (Na3PO4) can prevent pitting corrosion of steel in the simulated concrete pore solution if its concentration is equal to the chloride concentration [22]. The presence of phosphates in the mortar increases the critical period of pitting initiation from 30 to 100 days and significantly reduces the chloride diffusion rate. Moreover, the apparent chloride diffusion coefficient calculated for mortar containing Na3PO4·12H2O which is around 1.03 × 10−12 m2/s is lower than that obtained with the reference mortar (2.2 × 10−12 m2/s) for the same testing period [23].

The concentration of phosphate species inside the pits was higher than the passive film zones without the pit. This indicates that phosphate ions could inhibit the corrosion process through a competitive adsorption mechanism with chloride ions where the chloride attack triggers the phosphate species to further adsorb at the pit locations on the metal surface [24]. In addition, the presence of phosphate ions stabilizes ferrihydrite, a poorly crystallized FeOOH, which may be a protective layer for steel in Cl−-contaminated concrete simulating solutions [8]. As a counterpart, the inhibition efficiency of phosphate corrosion inhibitors is decreased in concrete because of the reaction of PO43− ions with the concrete matrix [25].

The surface analysis methods demonstrated that the inhibition mechanism of phosphate ions is attributed to the formation of a passive film with a duplex layer on the metal surface, including the inner layer of iron(hydro)oxides, formed by a solid-state mechanism and the outer layer of iron phosphate complexes mainly as FeHPO4, Fe3(PO4)2 and even Fe(PO4), formed via a dissolution–precipitation mechanism [24].

The impact of phosphate corrosion inhibitors on the stability of the passive film depends on the [Cl−]/[OH−] ratio. It can be explained by the fact that the high concentration of hydroxyl groups relative to chloride ions causes a predominant effect to form a robust passive film, which in turn stops the pitting corrosion without the aid of phosphate. This corrosion protection mechanism is associated with a continuous increase in the resistance of the passive film by adsorption of phosphate species in the weak points of the passive film, which block the anodic sites [26].

Studies performed under applied mechanical stress revealed that in the presence of phosphate corrosion inhibitors, the critical [Cl−]/[OH−] ratio increased from 0.4 to 5 for strained electrodes under stress conditions (80% UTS) [27].

The addition of phosphate corrosion inhibitors led to a decrease in chloride binding. This is mainly because phosphates hold a higher priority over chloride during ion exchange in Al2O3–Fe2O3-mono (AFm) and –tri (AFt) phases in the Ca–Al–S–O–H system of the concrete matrix. Moreover, phosphates exerted a significant influence on the chemical binding but a negligible effect on the physical binding [28].

More recently, the use of alternative pentasodium triphosphate compounds Na5P3O10, also known as sodium tripolyphospate, has shown an increased inhibition efficiency of around 80% for 480 days exposure in 3.5% NaCl, which is attributed to the development of a protective film barrier of PST on the steel rebar surface. Potentiodynamic polarization results revealed that PST affects the anodic and cathodic sites uniformly, thus presenting a mixed-type corrosion-inhibitor protection mechanism [29]. The use of inorganic corrosion-inhibitor mixtures containing hexametaphosphate compounds (NaPO3)6, used in 3.5% NaCl contained SCPS, have been proven to reduce the corrosion rate by 8.60 and 25.52 times for 3 and 5% inhibitor addition, respectively [30].

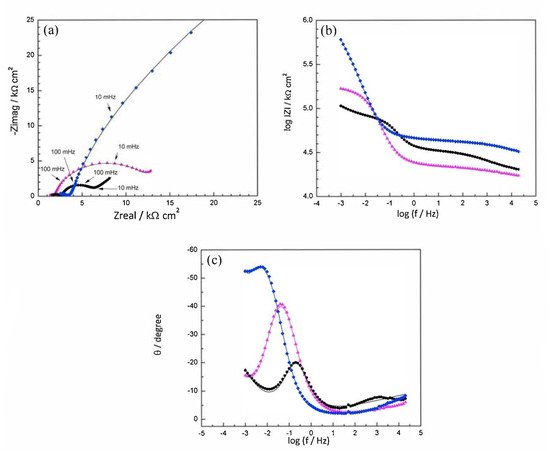

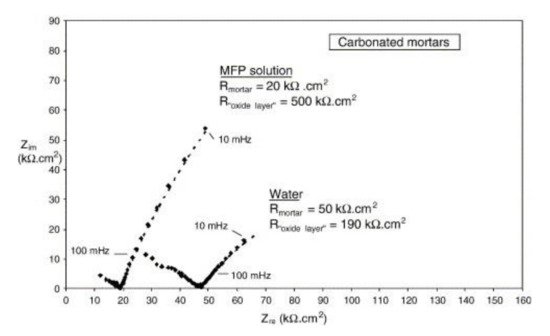

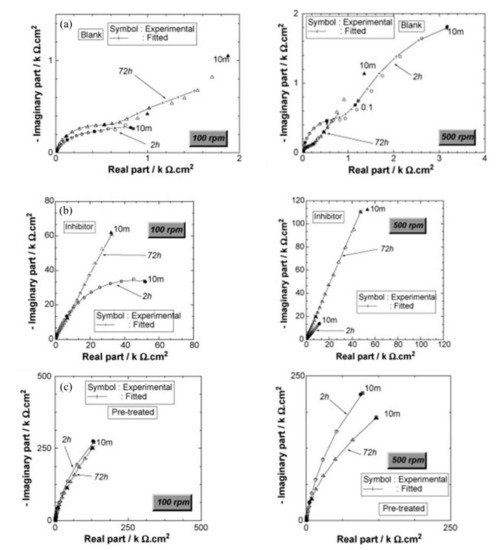

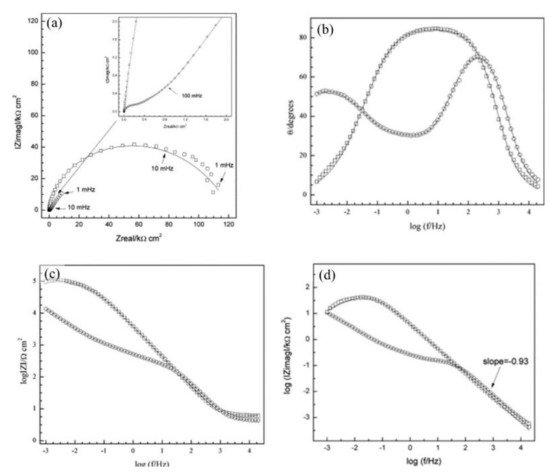

Disodium hydrogen phosphate (Na2HPO4, DHP) in simulated concrete pore solution (SCPS) and in mortar acts as an anodic corrosion inhibitor [18][21]. Overall, phosphates require oxygen to be effective, as they are nonoxidizing anodic inhibitors [31]. Trisodium phosphate (Na3PO4∙H2O, TSP) in mortar acts as a mixed corrosion inhibitor [32], as well as in chloride environments containing a [PO43−]/[Cl−] ratio higher than 0.6 [16][33] and even as a cathodic corrosion inhibitor, with a [PO43−]/[Cl−] ratio less than 0.6 [34]. Impedance techniques, such as electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), can be used to measure the corrosion improvement of inhibitors [35][20][32][36][37]. Yohai et al. showed in their work with mortars great corrosion enhancement of the TSP (Mix C), even with the chloride addition, over the blank (Mix A) and the chloride contaminated specimen (Mix B) (see Figure 2a), clearly seen in the Bode plot where Mix C is of one order of magnitude higher than the other two mixes (see Figure 2b) [32]. Similarly, Chaussadent et al. found an improvement in the corrosion protection by sodium monofluorophosphate as a corrosion inhibitor using the EIS results of mortar samples after carbonation (Figure 3) [38]. Another example of the use of EIS is the work from Etteyeb et al., in which the specimen containing inhibitors (see Figure 4a) increased its impedance by two orders of magnitude compared to the blank (see Figure 4b) [20].

Figure 2. EIS spectra for mix designs:

Mix A:  Mix B:

Mix B:  Mix C:

Mix C:  registered after 720 days of exposure. Points represent the experimental EIS data and lines show the fitting results: (a) Nyquist plot, (b) and (c) Bode plots [32]. Reproduced with permission from Yohai, L. et al., Electrochim. Acta; published by Elsevier, 2016.

registered after 720 days of exposure. Points represent the experimental EIS data and lines show the fitting results: (a) Nyquist plot, (b) and (c) Bode plots [32]. Reproduced with permission from Yohai, L. et al., Electrochim. Acta; published by Elsevier, 2016.

Mix B:

Mix B:  Mix C:

Mix C:  registered after 720 days of exposure. Points represent the experimental EIS data and lines show the fitting results: (a) Nyquist plot, (b) and (c) Bode plots [32]. Reproduced with permission from Yohai, L. et al., Electrochim. Acta; published by Elsevier, 2016.

registered after 720 days of exposure. Points represent the experimental EIS data and lines show the fitting results: (a) Nyquist plot, (b) and (c) Bode plots [32]. Reproduced with permission from Yohai, L. et al., Electrochim. Acta; published by Elsevier, 2016.

Figure 3. EIS diagrams for carbonated mortars at 48 h after application of aqueous solutions (MFP or water) [38]. Reproduced with permission from Chaussadent, T. et al., Cem. Conc. Res.; published by Elsevier, 2006.

Figure 4. Impedance diagrams (Nyquist representation) of (a) steel electrode/S1 solution, (b) steel electrode/S2 solution and (c) pretreated steel electrode/S1 solution; for two periods of immersion: 2 and 72 h and for two electrode rotation rate values: 100 and 500 rpm [20]. Reproduced with permission from Etteyeb, N. et al., Electrochim. Acta; published by Elsevier, 2007.

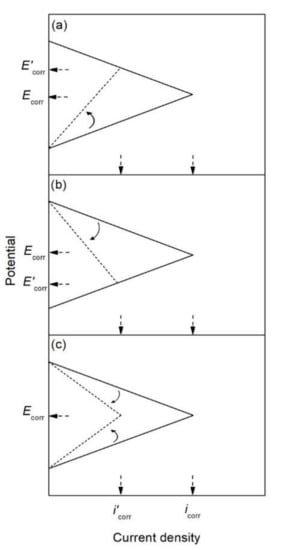

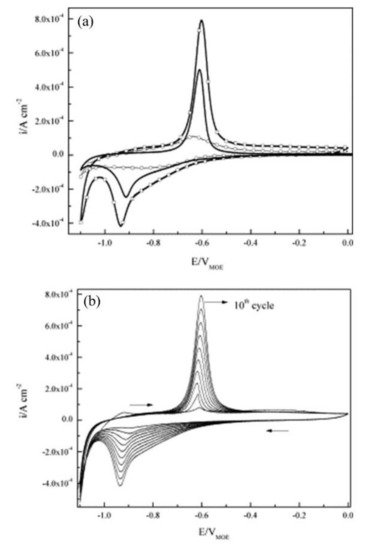

The corrosion inhibitor effect on the anodic and cathodic polarization curves can be seen in the Evans diagrams shown in Figure 5. This is in agreement with the findings of Yohai et al., in which [PO43−]/[Cl−] = 1 and phosphate behaves as a mixed inhibitor [37] and phosphate ions promote ferrous phosphate precipitation due to the higher solubility of ferric phosphate (pKsp = 26) than ferrous phosphate (pKsp = 32). The cyclic voltammograms in PSS, PSS + Cl− and PSS + Cl− + PO43− showed the presence of a single negative and positive peak, attributed to the accumulation of magnetite on the steel surface, which is not fully reduced (see Figure 6a) [37]. However, for the PO43− ions, which promote Fe3(PO4)2 precipitation, the difference was not substantial and is due to lack of formation of Fe3+ compound, hence not getting reduced in the following cycles (see Figure 6b). By the impedance fitting, the protectiveness of the PO43− ions was also seen, showing more ideal capacitors, which were related to the presence of a protective passive layer, however a small decrease in the impedance was associated with the change in the film composition, influencing the electronic properties (see Figure 7).

Figure 5. Evans diagrams showing the effect of a corrosion inhibitor, (a) on the anodic branch (anodic inhibitor), (b) on the cathodic branch (cathodic inhibitor), and (c) on both the anodic and cathodic branches (mixed inhibitor).

Figure 6. Cyclic voltammograms for steel: (a) (tenth cycle) in PSS (—), PSS + Cl− (–□–), PSS + Cl− + PO43− (–○–), and (b) cycles 1–10th in PSS + Cl−. Scan rate: 10 mV s−1 [37]. Reproduced with permission from Yohai, L. et al., Electrochim. Acta; Published by Elsevier, 2013.

Figure 7. Impedance spectra recorded on steel electrodes aged over 24 h at Ecorr in SSP + Cl− with and without inhibitor. The symbols represent the data and the lines the fitting results. (a) Nyquist representation, (b) and (c) Bode representation, and (d) imaginary part of impedance as function of frequency, in logarithmic scale. PSS + Cl− (–□–), PSS + Cl− + PO43− (–○–) [37]. Reproduced with permission from Yohai, L. et al., Electrochim. Acta; Published by Elsevier, 2013.

Calcium monofluorophosphate (CaPO3F) [39], as well as zinc monofluorophosphate (ZnPO3F) have been used as corrosion inhibitors for steel in 3 wt.% NaCl solution [40], in both cases, the inhibitors are shown to be effective. Manganese monofluorophosphate (MnPO3F) has been found to exhibit a mixed corrosion inhibition for steel in 3 wt.% NaCl solution [41]. Aluminum tri-polyphosphate (AlH2P3O10∙2H2O) has been used as an ACI inhibitor with good results [42].

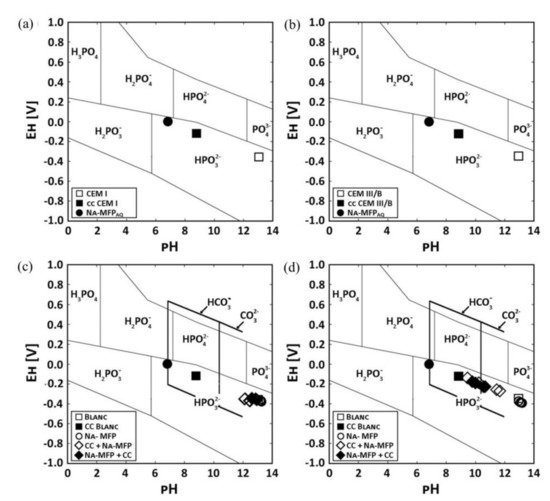

Figure 8 shows Pourbaix diagrams with the stability fields for phosphoric ions as well as EH−pH values of pore solution of two OPC pastes labelled CEM I and CEM III/B [43]. The use of sodium monofluorophosphate (Na2PO3F, MFP) dual inhibitor and self-healing agent was found to recover 98.85% and 79.82% of the pH of the carbonated cement pastes compared to the untreated paste for CEM I and CEM III/B, respectively. The pH increased for higher concentrations of sodium in the treating agent.

Figure 8. Pourbaix diagram of two different OPC cement pastes (CEM I and CEM III/B) showing the stability fields for phosphoric ions in solution and the EH−pH values of the pore solutions. pH values of the pore solutions from untreated CEM I, carbonated paste (cc) and the self-healing agent sodium monofluorophosphate (MFA) for: (a) CEM I and (b) CEM III/B, respectively. pH values of the pore solutions from paste samples that were either only impregnated with MFA or were first carbonated and impregnated with MFA (cc + MFA) or were impregnated with MFA and carbonated (MFA + cc) for: (c) CEM I and (d) CEM III/B, respectively. The thick black lines frame the stability of HCO3− and CO32− [43]. Reproduced with permission from Kempl, J. et al., Cem. Conc. Comp.; Published by Elsevier, 2016.

References

- Wu, M.; Johannesson, B.; Geiker, M. A review: Self-healing in cementitious materials and engineered cementitious composite as a self-healing material. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 28, 571–583.

- Fajardo, S.; Bastidas, J.M.; Criado, M.; Romero, M. Corrosion behaviour of a new low-nickel stainless steel in saturated calcium hydroxide solution. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 4190–4196.

- Page, C.L.; Treadaway, K.W.J. Aspects of the electrochemistry of steel in concrete. Nat. Cell Biol. 1982, 297, 109–115.

- González, J.A. 2007 FN Speller award lecture: Prediction of reinforced concrete structure durability by electrochemical techniques. Corrosion 2007, 63, 811–818.

- Dong, B.; Wang, Y.; Ding, W.; Li, S.; Han, N.; Xing, F.; Lu, Y. Electrochemical impedance study on steel corrosion in the simulated concrete system with a novel self-healing microcapsule. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 56, 1–6.

- Ormellese, M.; Lazzari, L.; Goidanich, S.; Fumagalli, G.; Brenna, A. A study of organic substances as inhibitors for chloride-induced corrosion in concrete. Corros. Sci. 2009, 51, 2959–2968.

- Ress, J.; Martin, U.; Bosch, J.; Bastidas, D.M. pH-triggered release of NaNO2 corrosion inhibitors from novel colophony microcapsules in simulated concrete pore solution. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 46686–46700.

- Génin, J.-M.R.; Dhouibi, L.; Refait, P.; Abdelmoula, M.; Triki, E. Influence of phosphate on corrosion products of iron in chloride-polluted-concrete-simulating solutions: Ferrihydrite vs. green rust. Corrosion 2002, 58, 467–478.

- Soeda, K.; Ichimura, T. Present state of corrosion inhibitors in Japan. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2003, 25, 117–122.

- Tritthart, J. Transport of a surface-applied corrosion inhibitor in cement paste and concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2003, 33, 829–834.

- De Gutierrez, R.M.; Aguirre, A.M. Durabilidad del hormigón armado expuesto a condiciones agresivas. Mater. Constr. 2013, 63, 7–38.

- Lee, H.-S.; Saraswathy, V.; Kwon, S.-J.; Karthick, S. Corrosion inhibitors for reinforced concrete: A review. In Corrosion Inhibitors, Principles and Recent Applications; Aliofkhazraei, M., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018; pp. 95–120.

- Page, M.M.; Ngala, V.T.; Page, C.L. Corrosion inhibitors in concrete repair systems. Mag. Concr. Res. 2000, 52, 25–37.

- Li, W.; Dong, B.; Yang, Z.; Xu, J.; Chen, Q.; Li, H.; Xing, F.; Jiang, Z. Recent advances in intrinsic self-healing cementitious materials. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, e1705679.

- Ngala, V.; Page, C.; Page, M. Corrosion inhibitor systems for remedial treatment of reinforced concrete. Part 2: Sodium monofluorophosphate. Corros. Sci. 2003, 45, 1523–1537.

- Söylev, T.A.; Richardson, M. Corrosion inhibitors for steel in concrete: State-of-the-art report. Constr. Build. Mater. 2008, 22, 609–622.

- Bastidas, D.M.; La Iglesia, V.M.; Criado, M.; Fajardo, S.; La Iglesia, A.; Bastidas, J.M. A prediction study of hydroxyapatite entrapment ability in concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 2646–2649.

- Bastidas, D.M.; Criado, M.; La Iglesia, V.M.; Fajardo, S.; La Iglesia, A.; Bastidas, J.M. Comparative study of three sodium phosphates as corrosion inhibitors for steel reinforcements. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2013, 43, 31–38.

- Criado, M.; Bastidas, D.M.; La Iglesia, V.M.; La Iglesia, A.; Bastidas, J.M. Precipitation mechanism of soluble phosphates in mortar. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2017, 23, 1265–1274.

- Etteyeb, N.; Dhouibi, L.; Takenouti, H.; Alonso, M.; Triki, E. Corrosion inhibition of carbon steel in alkaline chloride media by Na3PO4. Electrochim. Acta 2007, 52, 7506–7512.

- Bastidas, D.M.; Criado, M.; Fajardo, S.; La Iglesia, A.; Bastidas, J.M. Corrosion inhibition mechanism of phosphates for early-age reinforced mortar in the presence of chlorides. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2015, 61, 1–6.

- Dhouibi, L.; Triki, E.; Raharinaivo, A.; Trabanelli, G.; Zucchi, F. Electrochemical methods for evaluating inhibitors of steel corrosion in concrete. Br. Corros. J. 2000, 35, 145–149.

- Nahali, H.; Ben Mansour, H.; Dhouibi, L.; Idrissi, H. Effect of Na3PO4 inhibitor on chloride diffusion in mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 141, 589–597.

- Iravani, D.; Arefinia, R. Effectiveness of one-to-one phosphate to chloride molar ratio at different chloride and hydroxide concentrations for corrosion inhibition of carbon steel. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 233, 117200.

- Shi, J.-J.; Sun, W. Electrochemical and analytical characterization of three corrosion inhibitors of steel in simulated concrete pore solutions. Int. J. Miner. Met. Mater. 2012, 19, 38–47.

- Mohagheghi, A.; Arefinia, R. Corrosion inhibition of carbon steel by dipotassium hydrogen phosphate in alkaline solutions with low chloride contamination. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 187, 760–772.

- Ben Mansour, H.; Dhouibi, L.; Idrissi, H. Effect of phosphate-based inhibitor on prestressing tendons corrosion in simulated concrete pore solution contaminated by chloride ions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 171, 250–260.

- Chen, Y.; Jiang, L.; Yan, X.; Song, Z.; Guo, M.; Zhao, S.; Gong, W. Impact of phosphate corrosion inhibitors on chloride binding and release in cement pastes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 236, 117469.

- Paulson, B.M.; Thomas, K.J.; Raphael, V.P.; Shaju, K.S.; Ragi, K. Mitigation of concrete reinforced steel corrosion by penta sodium triphosphate: Physicochemical and electrochemical investigations. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1–11.

- Lee, H.-S.; Yang, H.-M.; Singh, J.K.; Prasad, S.K.; Yoo, B. Corrosion mitigation of steel rebars in chloride contaminated concrete pore solution using inhibitor: An electrochemical investigation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 173, 443–451.

- Simões, A.; Torres, J.; Picciochi, R.; Fernandes, J. Corrosion inhibition at galvanized steel cut edges by phosphate pigments. Electrochim. Acta 2009, 54, 3857–3865.

- Yohai, L.; Valcarce, M.; Vázquez, M. Testing phosphate ions as corrosion inhibitors for construction steel in mortars. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 202, 316–324.

- Dhouibi, L.; Triki, E.; Salta, M.; Rodrigues, P.; Raharinaivo, A. Studies on corrosion inhibition of steel reinforcement by phosphate and nitrite. Mater. Struct. 2003, 36, 530–540.

- Shi, J.; Sun, W. Effects of phosphate on the chloride-induced corrosion behavior of reinforcing steel in mortars. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2014, 45, 166–175.

- Ress, J.; Martin, U.; Bosch, J.; Bastidas, D.M. Protection of carbon steel rebars by epoxy coating with smart environmentally friendly microcapsules. Coatings 2021, 11, 113.

- Bastidas, D.M. Interpretation of impedance data for porous electrodes and diffusion processes. Corrosion 2007, 63, 515–521.

- Yohai, L.; Vazquez, M.; Valcarce, M. Phosphate ions as corrosion inhibitors for reinforcement steel in chloride-rich environments. Electrochim. Acta 2013, 102, 88–96.

- Chaussadent, T.; Nobel-Pujol, V.; Farcas, F.; Mabille, I.; Fiaud, C. Effectiveness conditions of sodium monofluorophosphate as a corrosion inhibitor for concrete reinforcements. Cem. Concr. Res. 2006, 36, 556–561.

- Laamari, M.; Derja, A.; Benzakour, J.; Berraho, M. Calcium monofluorophosphate: A new class of corrosion inhibitors in NaCl medium. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2004, 569, 1–6.

- Loqmane, S.; Laamari, R.; Derja, A.; Berraho, M. Synthesis and characterization of ZnPO3F,5/2H2O – Evaluation of its anticorrosion properties vis a vis iron substrates. Ann. Chim. Sci. Mater. 2000, 25, 127–141.

- Laamari, M.R.; Derja, A.; Benzakour, J.; Berrekhis, F. Contribution to study corrosion inhibition of iron by manganese monofluorophosphate. Curr. Top. Electrochem. 2010, 5, 45–52.

- Feng, X.; Shi, R.; Lu, X.; Xu, Y.; Huang, X.; Chen, D. The corrosion inhibition efficiency of aluminum tripolyphosphate on carbon steel in carbonated concrete pore solution. Corros. Sci. 2017, 124, 150–159.

- Kempl, J.; Copuroglu, O. EH-pH- and main element analyses of blast furnace slag cement paste pore solutions activated with sodium monofluorophosphate—implications for carbonation and self-healing. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016, 71, 63–76.

More

Information

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.2K

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

28 Mar 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No