| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nesrin Ada | + 3981 word(s) | 3981 | 2021-06-21 08:08:13 | | | |

| 2 | Bruce Ren | -21 word(s) | 3960 | 2021-06-29 05:54:29 | | | | |

| 3 | Bruce Ren | Meta information modification | 3960 | 2021-06-30 10:14:40 | | | | |

| 4 | Bruce Ren | -4 word(s) | 3956 | 2021-06-30 10:15:11 | | | | |

| 5 | Bruce Ren | -4 word(s) | 3956 | 2021-06-30 10:15:52 | | |

Video Upload Options

The concept of the circular economy (CE) has gained importance worldwide recently since it offers a wider perspective in terms of promoting sustainable production and consumption with limited resources. However, few studies have investigated the barriers to CE in circular food supply chains.

1. Introduction

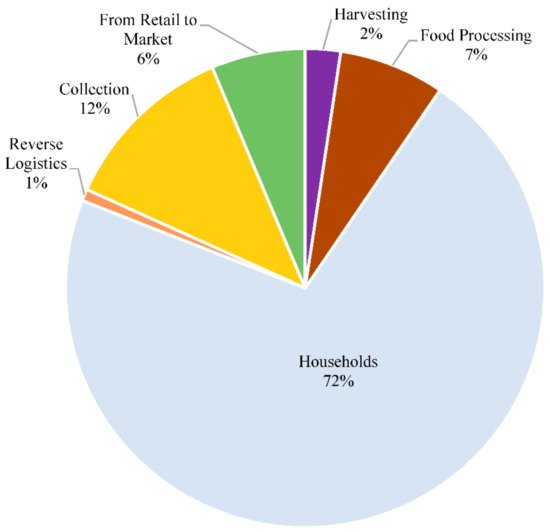

According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, one third of food produced is lost or wasted every year [1]. The report also notes differences between low- and medium-, and high-income countries in terms of the losses at various stages of supply chains. In low- and medium-income countries, food loss mostly occurs at the beginning of the production and supply chains whereas food in high-income countries is thrown away by retailers or consumers to become food waste at the consumption stage [1]. Additionally, the reasons for food losses and waste vary by countries’ income level. In low-income countries, the causes are mostly related to financial restrictions and lack of technical knowledge in harvesting techniques and infrastructure whereas in medium or high-income countries the causes are connected to consumer behaviors and lack of coordination among stakeholders in the food supply chain.

Overall, increasing food waste is becoming a global issue regarding food security, which requires simultaneous management of environmental, economic, and social impacts. In order to eliminate these impacts, it is crucial to create a more sustainable food supply chain. Therefore, the concept of the CE has recently emerged as a response to the current linearity of the food supply chain. It offers an alternative method to the unsustainable linear economic model, which is identified with the ‘take, make, and dispose’ trilogy [2]. Moreover, increasing urbanization poses new challenges globally. More than half of the world’s population already live in urban areas, and this proportion is anticipated to rise to 80% by 2050 [3]. Meanwhile, the tremendously increasing world population increases demand for resources in urban regions as well as causing environmental problems, socio-economic inequalities, and new energy needs [4].

As a sustainable economic method, CE reduces the extraction of raw materials and enables recirculation of resources, thereby creating advantageous environments for both societies and industries. [5]. Among the many aims of CE, the most important is keeping materials available to decrease waste and energy use instead of disposing of them [6]. However, implementing CE requires both radical alternative economic solutions and novel management of resources [7]. CE mainly aims to resolve problems of resource use, waste, and emissions throughout the supply chain. These goals can be achieved by offering products, components, and materials with the minimum possible waste or even zero waste [8][9][10].

The transition from a linear economy to CE has created many requirements, such as increasing product reliability and quality [11]. Due to increased forward and reverse activities in the supply chain, businesses also need to adapt themselves to manage these dynamic characteristics and deal with multiple stakeholders and unpredictable conditions. To achieve CE, it is necessary to deal with various obstacles, such as strict legal regulations, high technology investment, company corporate culture, and insufficient knowledge of CE. While moving towards CE, many business models require a fundamental change to find new sustainable solutions. Businesses must therefore understand and overcome the challenges and barriers of CE to ensure sustainable development.

Despite its importance, few studies have integrated CE philosophy into the food supply chain [12][13]. It is also necessary to analyze the challenges during the transition to CE. While some studies have investigated obstacles to CE implementations [14][15][16], few studies have considered how digital technologies can be used to tackle CE barriers. Therefore, it is important to fill this gap [17]. Accordingly, this paper systematically analyzes the barriers to implementing CE in the food supply chain. It is important to understand current challenges, as viewed by industry, academics, and policymakers, to encourage future research, support companies, and determine the necessary regulations to move towards CE. Then, the importance of digital technologies is presented in order to overcome CE barriers.

The main research objectives of this study are as follows:

-To investigate the key barriers when implementing CE dimensions in the food supply chain;

-To systematically categorize CE dimensions for the food supply chain to overcome challenges;

-To analyze interaction effects between CE dimensions and food supply chain stages and between CE dimensions and sub-sectors of the food industry;

-To determine the benefits of digital technologies to overcome CE challenges in the food supply chain.

2. Analyses of CE Barriers in the Food Supply Chain

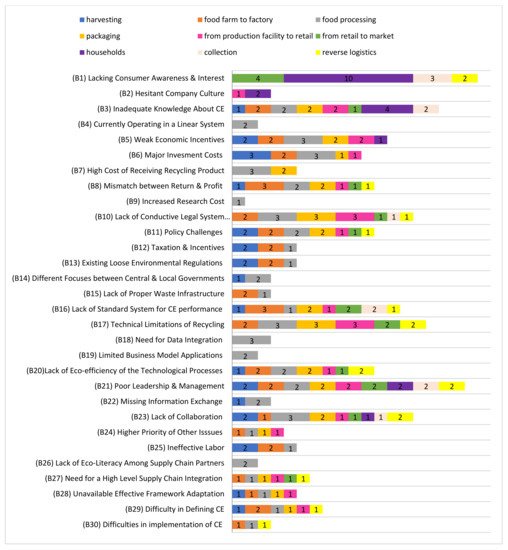

| Barriers | Sub-Barriers | Author(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Cultural | (B1) Lacking Consumer Awareness and Interest | [11][13][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50]. |

| (B2) Hesitant Company Culture | [13][27][28][29][30][51] | |

| (B3) Inadequate Knowledge About CE | [13][27][28][35][38][39][42][43][45][46][47][51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60] | |

| (B4) Currently Operating in a Linear System | [61][62] | |

| Business and Business Finance | (B5) Weak Economic Incentives | [25][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][58][63][64] |

| (B6) Major Investment Costs | [41][42][45][46][65][66] | |

| (B7) High Cost of Receiving Recycling Product | [28][29][39][43][45][46][64] | |

| (B8) Mismatch between Return and Profit | ||

| (B9) Increased Research Cost | [38][41][45][46] | |

| (B10) Limited Business Model Applications | [66] | |

| [42][44] | ||

| Regulatory and Governmental | (B11) Lack of Conductive Legal Systems | [14][22][28][37][39][40][44][45][46][52] |

| (B12) Policy Challenges | [11][13][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][50]. | |

| [14][39][43][45][46] | ||

| (B13) Taxation and Incentives | [23][25][34][59][67] | |

| (B14) Existing Loose Environmental Regulations | ||

| (B15) Different Focuses between Central and Local Governments | [36][50][68] | |

| (B16) Lack of Proper Waste Infrastructure | ||

| (B17) Lack of Standard System for CE performance | [36][40][54][56][57][69][70][71][72] | |

| [23][30][36][42][45][46][51][53][54][56][57][69][70][71][72][73][74][75] | ||

| Technological | (B18) Technical Limitations of Recycling | [13][28][29][39][42][44][45][46][52][59][63][65] |

| (B19) Need for Data Integration | [24][76] | |

| (B20) Lack of Eco-efficiency of the Technological Processes | [16][39][45][46][52][77] | |

| Managerial | (B21) Poor Leadership and Management | [11][12][23][26][29][30][32][40][42][45][46][78][79][80][81] |

| (B22) Missing Information Exchange | [11][45][46] | |

| (B23) Lack of Collaboration | [12][15][22][32][39][42][43][45][59][74][75][76][78][81] | |

| (B24) Higher priority of other issues | [45][82] | |

| (B25) Ineffective labor | [83][66] | |

| Supply Chain Management | (B26) Lack of Eco-Literacy Among Supply Chain Partners | [39][84][85] |

| (B27) Need for a High-Level Supply Chain Integration | [11][12][23][26][30][32][33][39][42][45][46][50][69][74][75][79][80][82][84][86][87][88][89][90][91][92][93][94][95][96] | |

| (B28) Unavailable Effective Framework Adaptation | ||

| [46][78][97] | ||

| Knowledge and Skills | (B29) Difficulty in Defining CE | [30][42][98][99] |

| (B30) Difficulties in implementation of CE | [30][42][45][98][99][100][101][102] |

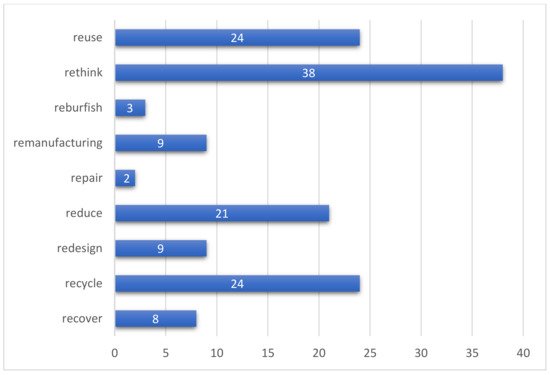

3. Relationships Between CE and Digital Technologies

| CE DIMENSIONS | INDUSTRY 4.0 TECHNOLOGIES |

|---|---|

| Reuse | CPS, BDA, AI, 3DP, RFID, Barcodes, Nanotechnologies, Blockchain |

| Recycle | IoT, CPS, BDA, CC, AI,3DP, RFID, Barcodes, Blockchain |

| Reduce | IoT, 3DP |

| Remanufacturing | IoT, BDA, CC, AI, 3DP, RFID, Barcodes, Robotics |

| Repair | IoT, CPS, BDA, 3DP |

| Recover | CC |

| Refurbish | CPS, AI |

| Repurpose | Machine Learning |

| Rethink | AGV, Machine Learning |

| Redesign | Iot, AGV, Machine Learning |

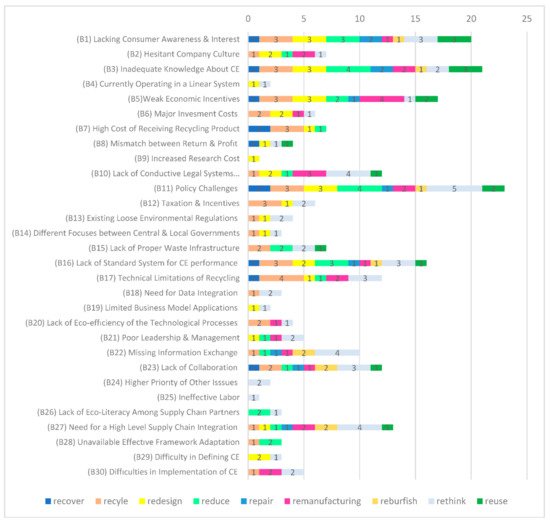

| Main Barriers | Sub-Barriers | Author(s) | CE Dimensions | Industry 4.0 Technologies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural | (B1) Lacking consumer awareness and interest | [113][114][115][116][117][118][119][120] | Reuse, Recycle, Reduce, Rethink, Remanufacturing, Redesign, Repair, Refurbish | IoT, CPS, BDA, CC, AI, 3DP, RFID, Barcodes, Robotics, Blockchains, AGV, Machine learning, Nanotechnology |

| (B2) Hesitant company culture | [121][122][117][123][119][124] | Reuse, Recycle, Reduce, Remanufacturing, Repair, Refurbish | IoT, CPS, BDA, CC, AI, 3DP, RFID, Barcodes, Robotics, Blockchains, Nanotechnology | |

| (B3) Inadequate knowledge about CE | [125][126][117][119][127] | Reuse, Recycle, Reduce, Remanufacturing, Repair, Refurbish, Rethink | IoT, CPS, BDA, CC, AI, 3DP, RFID, Barcodes, Robotics, Blockchains, AGV, Machine learning, Nanotechnology | |

| (B4) Currently operating in a linear system | [128][129][117][130][124] | Reuse, Reduce, Rethink | IoT, CPS, BDA, AI, 3DP, RFID, Barcodes, Blockchains, AGV, Machine learning, Nanotechnology | |

| Business and Business Finance | (B5) Weak economic incentives | [121][131][117][118][119][120] | Reuse, Recycle, Reduce, Remanufacturing, Repair, Refurbish, Rethink, Redesign | IoT, CPS, BDA, CC, AI, 3DP, RFID, Barcodes, Robotics, Blockchains, AGV, Machine learning, Nanotechnology |

| (B6) Major investment costs | [129][120] | Repurpose, Rethink | AGV, Machine Learning | |

| (B7) High cost of receiving recycling product | [131][124] | Rethink | AGV, Machine Learning | |

| (B8) Mismatch between return and profit | [131][129] | Rethink | AGV, Machine Learning | |

| (B9) Increased research cost | [131][127] | Repurpose, Rethink | AGV, Machine Learning | |

| (B10) Limited business model applications | [117][130][132][127] | Repair, Rethink | IoT, CPS, BDA, 3DP, AGV, Machine learning | |

| Regulatory and Governmental | (B11) Lack of conductive legal systems | [107][133][134][131][122][117][119] | Reuse, Recycle, Reduce, Remanufacturing, Repair, Refurbish, Rethink | IoT, CPS, BDA, CC, AI, 3DP, RFID, Barcodes, Robotics, Blockchains, AGV, Machine learning, Nanotechnology |

| (B12) Policy challenges | [114][115][135][136][117][137][119] | Reuse, Recycle, Reduce, Remanufacturing, Repair, Recover, Refurbish, Rethink, Redesign | IoT, CPS, BDA, AI, 3DP, CC, Blockchains, Robotics, AGV, Machine Learning | |

| (B13) Taxation and incentives | [138][114][126][131][129][117][118][119] | Reuse, Recycle, Reduce, Rethink | IoT, CPS, BDA, CC, AI, 3DP, RFID, Barcodes, Robotics, Blockchains, AGV, Machine learning, Nanotechnology | |

| (B14) Existing loose environmental regulations | [114][139][136][117][123][119][120] | Reuse, Recycle, Reduce, Recover, Rethink | IoT, CPS, BDA, CC, AI, 3DP, RFID, Barcodes, Robotics, Blockchains, AGV, Machine learning, Nanotechnology | |

| (B15) Different focuses between central and local governments | [114][140][129][117][130][119] | Reuse, Recycle, Reduce, Remanufacturing, Repair, Rethink | IoT, CPS, BDA, CC, AI, 3DP, Robotics, Blockchains, AGV, Machine learning | |

| (B16) Lack of proper waste infrastructure | [114][129][132] | Rethink, Reduce | IoT, AGV, 3DP, Machine learning | |

| (B17) Lack of standard system for CE performance | [114][134][128][129][117][130][119] | Reuse, Recycle, Reduce, Remanufacturing, Recover, Refurbish, Rethink | IoT, CPS, BDA, CC, AI, 3DP, RFID, Barcodes, Robotics, Blockchains, AGV, Machine learning, Nanotechnology | |

| Technological | (B18) Technical limitations of recycling | [121][117][132][119][120] | Reuse, Recycle, Reduce, Remanufacturing, Repair, Refurbish, Rethink, Redesign | IoT, CPS, BDA, CC, AI, 3DP, RFID, Barcodes, Robotics, Blockchains, AGV, Machine learning, Nanotechnology |

| (B19) Need for data integration | [117][137][123][127] | Reuse, Recycle, Reduce, Rethink | IoT, CPS, BDA, CC, AI, 3DP, RFID, Barcodes, Blockchains, AGV, Machine learning, Nanotechnology | |

| (B20) Lack of eco-efficiency of the technological processes | [134][128][129][117][132][119] | Reuse, Recycle, Remanufacturing, Rethink | IoT, CPS, BDA, CC, AI, 3DP, RFID, Barcodes, Robotics, Blockchains, AGV, Machine learning, Nanotechnology | |

| Managerial | (B21) Poor leadership and management | [114][117][118][119][124] | Reuse, Recycle, Reduce, Remanufacturing, Repair, Recover, Rethink | IoT, CPS, BDA, CC, AI, 3DP, RFID, Barcodes, Robotics, Blockchains, AGV, Machine learning, Nanotechnology |

| (B22) Missing information exchange | [138][114][117][119][124] | Reuse, Recycle, Remanufacturing, Repair | IoT, CPS, BDA, CC, AI, 3DP, RFID, Barcodes, Robotics, Blockchains, Nanotechnology | |

| (B23) Lack of collaboration | [107][113][114][117][119] | Reuse, Recycle, Reduce, Rethink, Redesign | IoT, CPS, BDA, CC, AI, 3DP, RFID, Barcodes, Blockchains, AGV, Machine learning, Nanotechnology | |

| (B24) Higher priority of other issues | [131][129][127] | Rethink | AGV, Machine learning | |

| (B25) Ineffective labor | [136][117][120] | Repurpose, Rethink | AGV, Machine learning | |

| Supply chain management | (B26) Lack of eco-literacy among supply-chain partners | [129][117][127] | Reuse, Recycle, Reduce, Rethink | IoT, CPS, BDA, CC, AI, 3DP, RFID, Barcodes, Blockchains, AGV, Machine learning, Nanotechnology |

| (B27) Need for a high-level supply chain integration | [113][117][130][119][127] | Reuse, Recycle, Reduce, Remanufacturing, Repair, Recover, Rethink | IoT, CPS, BDA, CC, AI, 3DP, RFID, Barcodes, Robotics, Blockchains, AGV, Machine learning, Nanotechnology | |

| (B28) Unavailable effective framework adaptation | [117][137][130][124] | Reuse, Recycle, Reduce, Rethink | IoT, CPS, BDA, CC, AI, 3DP, RFID, Barcodes, Blockchains, AGV, Machine learning, Nanotechnology | |

| Knowledge and Skills | (B29) Difficulty in defining CE | [117][119][124] | Reuse, Recycle, Reduce, Remanufacturing, Refurbish, Repurpose, Rethink | IoT, CPS, BDA, CC, AI, 3DP, RFID, Barcodes, Robotics, Blockchains, AGV, Machine learning, Nanotechnology |

| (B30) Difficulties in implementation of CE | [128][117][123][118][119] | Reuse, Recycle, Reduce, Remanufacturing, Refurbish, Rethink | IoT, CPS, BDA, CC, AI, 3DP, RFID, Barcodes, Robotics, Blockchains, AGV, Machine learning, Nanotechnology |

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The State of Food and Agriculture 2019: Moving Forward on Food Loss and Waste Reduction; CCBY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2019; Available online: (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Ness, D. Sustainable urban infrastructure in China: Towards a Factor 10 improvement in resource productivity through integrated infrastructure systems. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2008, 15, 288–301.

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision (ST/ESA/SER.A/420) 2019; United Nations: New York, NY, USA; Available online: (accessed on 18 February 2020).

- ENEL. Cities of Tomorrow, Circular Cities. 2018. Available online: (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Corona, B.; Shen, L.; Reike, D.; Carreón, J.R.; Worrell, E. Towards Sustainable Development through the Circular Economy—A Review and Critical Assessment on Current Circularity Metrics. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 151, 104498.

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards the Circular Economy: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition. Available online: (accessed on 21 June 2020).

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A Review on Circular Economy: The Expected Transition to a Balanced Interplay of Environmental and Economic Systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32.

- Paes, L.A.B.; Bezerra, B.S.; Deus, R.M.; Jugend, D.; Battistelle, R.A.G. Organic solid waste management in a circular economy perspective–A systematic review and SWOT analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 239, 118086.

- Zhu, J.; Fan, C.; Shi, H.; Shi, L. Efforts for a Circular Economy in China: A Comprehensive Review of Policies. J. Ind. Ecol. 2019, 23, 110–118.

- Pietzsch, N.; Ribeiro, J.L.D.; de Medeiros, J.F. Benefits, challenges and critical factors of success for Zero Waste: A systematic literature review. Waste Manag. 2017, 67, 324–353.

- Avraamidou, S.; Baratsas, S.G.; Tian, Y.; Pistikopoulos, E.N. Circular Economy—A challenge and an opportunity for Process Systems Engineering. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2020, 133, 106629.

- Farooque, M.; Zhang, A.; Liu, Y. Barriers to circular food supply chains in China. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2019, 24, 677–696.

- Sharma, Y.K.; Mangla, S.K.; Patil, P.P.; Liu, S. When challenges impede the process: For circular economy-driven sustainability practices in food supply chain. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 995–1017.

- Govindan, K.; Hasanagic, M. A systematic review on drivers, barriers, and practices towards circular economy: A supply chain perspective. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 278–311.

- Bressanelli, G.; Perona, M.; Saccani, N. Challenges in supply chain redesign for the Circular Economy: A literature review and a multiple case study. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 7395–7422.

- Pagoropoulos, A.; Pigosso, D.C.A.; McAloone, T.C. The Emergent Role of Digital Technologies in the Circular Economy: A Review. Procedia CIRP 2017, 64, 19–24.

- Bressanelli, G.; Adrodegari, F.; Perona, M.; Saccani, N. Exploring How Usage-Focused Business Models Enable Circular Economy through Digital Technologies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 639.

- Galvão, G.D.A.; de Nadae, J.; Clemente, D.H.; Chinen, G.; de Carvalho, M.M. Circular Economy: Overview of Barriers. Procedia CIRP 2018, 73, 79–85.

- Kirchherr, J.; Piscicelli, L.; Bour, R.; Kostense-Smit, E.; Muller, J.; Huibrechtse-Truijens, A.; Hekkert, M. Barriers to the Circular Economy: Evidence From the European Union (EU). Ecol. Econ. 2018, 150, 264–272.

- Ghadge, A.; Kara, M.E.; Mogale, D.G.; Choudhary, S.; Dani, S. Sustainability Implementation Challenges in Food Supply Chains: A Case of UK Artisan Cheese Producers. Prod. Plan. Control. 2020, 1–16.

- Van Keulen, M.; Kirchherr, J. The implementation of the Circular Economy: Barriers and enablers in the coffee value chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 281, 125033.

- DeLorenzo, A.; Parizeau, K.; Von Massow, M. Regulating Ontario’s circular economy through food waste legislation. Soc. Bus. Rev. 2019, 14, 200–216.

- Mena, C.; Adenso-Diaz, B.; Yurt, O. The causes of food waste in the supplier–retailer interface: Evidences from the UK and Spain. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2011, 55, 648–658.

- Parfitt, J.; Barthel, M.; Macnaughton, S. Food waste within food supply chains: Quantification and potential for change to 2050. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 3065–3081.

- Pan, S.-Y.; Du, M.A.; Huang, I.-T.; Liu, I.-H.; Chang, E.-E.; Chiang, P.-C. Strategies on implementation of waste-to-energy (WTE) supply chain for circular economy system: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 409–421.

- Sehnem, S.; Ndubisi, N.O.; Preschlack, D.; Bernardy, R.J.; Santos, S., Jr. Circular economy in the wine chain production: Maturity, challenges, and lessons from an emerging economy perspective. Prod. Plan. Control. 2019, 31, 1014–1034.

- Jurgilevich, A.; Birge, T.; Kentala-Lehtonen, J.; Korhonen-Kurki, K.; Pietikäinen, J.; Saikku, L.; Schösler, H. Transition towards Circular Economy in the Food System. Sustainability 2016, 8, 69.

- Russell, M.; Gianoli, A.; Grafakos, S. Getting the ball rolling: An exploration of the drivers and barriers towards the implementation of bottom-up circular economy initiatives in Amsterdam and Rotterdam. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2019, 63, 1903–1926.

- Ritzén, S.; Sandström, G. Ölundh Barriers to the Circular Economy—Integration of Perspectives and Domains. Procedia CIRP 2017, 64, 7–12.

- Korhonen, J.; Honkasalo, A.; Seppälä, J. Circular Economy: The Concept and its Limitations. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 143, 37–46.

- Slorach, P.C.; Jeswani, H.K.; Cuéllar-Franca, R.; Azapagic, A. Environmental and economic implications of recovering resources from food waste in a circular economy. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 693, 133516.

- Özbük, R.M.Y.; Coşkun, A. Factors affecting food waste at the downstream entities of the supply chain: A critical review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118628.

- Cakar, B.; Aydin, S.; Varank, G.; Ozcan, H.K. Assessment of environmental impact of FOOD waste in Turkey. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118846.

- Vaneeckhaute, C.; Fazli, A. Management of ship-generated food waste and sewage on the Baltic Sea: A review. Waste Manag. 2020, 102, 12–20.

- Secondi, L. Expiry Dates, Consumer Behavior, and Food Waste: How Would Italian Consumers React If There Were No Longer “Best Before” Labels? Sustainability 2019, 11, 6821.

- Cerciello, M.; Agovino, M.; Garofalo, A. Estimating urban food waste at the local level: Are good practices in food consumption persistent? Econ. Politica 2018, 36, 863–886.

- Munesue, Y.; Masui, T. The impacts of Japanese food losses and food waste on global natural resources and greenhouse gas emissions. J. Ind. Ecol. 2019, 23, 1196–1210.

- Zhang, A.; Venkatesh, V.; Liu, Y.; Wan, M.; Qu, T.; Huisingh, D. Barriers to smart waste management for a circular economy in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 240, 118198.

- Bianchini, A.; Rossi, J.; Pellegrini, M. Overcoming the Main Barriers of Circular Economy Implementation through a New Visualization Tool for Circular Business Models. Sustainablity 2019, 11, 6614.

- Fedotkina, O.; Gorbashko, E.; Vatolkina, N. Circular Economy in Russia: Drivers and Barriers for Waste Management Development. Sustainablity 2019, 11, 5837.

- Garcés-Ayerbe, C.; Rivera-Torres, P.; Suárez-Perales, I.; La Hiz, D.I.L.-D. Is It Possible to Change from a Linear to a Circular Economy? An Overview of Opportunities and Barriers for European Small and Medium-Sized Enterprise Companies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2019, 16, 851.

- Tura, N.; Hanski, J.; Ahola, T.; Ståhle, M.; Piiparinen, S.; Valkokari, P. Unlocking circular business: A framework of barriers and drivers. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 90–98.

- Fux, H. What is the ideal scenario for circular economy to occur? A case study of the CircE project. Braz. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2019, 16, 157–165.

- Obersteg, A.; Arlati, A.; Acke, A.; Berruti, G.; Czapiewski, K.; Dąbrowski, M.; Heurkens, E.; Mezei, C.; Palestino, M.F.; Varjú, V.; et al. Urban Regions Shifting to Circular Economy: Understanding Challenges for New Ways of Governance. Urban Plan. 2019, 4, 19–31.

- Hart, J.; Adams, K.; Giesekam, J.; Tingley, D.D.; Pomponi, F. Barriers and drivers in a circular economy: The case of the built environment. Procedia CIRP 2019, 80, 619–624.

- Urbinati, A.; Davide, C.; Vittorio, C. Towards a new taxonomy of circular economy business models. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 487–498.

- Berardi, P.; Betiol, L.; Dias, J. Food waste and circular economy through public policies: Portugal & Brazil. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference Wastes: Solutions, Treatments and Opportunities III, Lisbon, Portugal, 4–6 September 2019; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; pp. 99–105.

- Yui, S.; Biltekoff, C. How Food Becomes Waste: Students as “Carriers of Practice” in the UC Davis Dining Commons. J. Hunger. Environ. Nutr. 2020, 1–22.

- Papargyropoulou, E.; Steinberger, J.K.; Wright, N.; Lozano, R.; Padfield, R.; Ujang, Z. Patterns and Causes of Food Waste in the Hospitality and Food Service Sector: Food Waste Prevention Insights from Malaysia. Sustainablility 2019, 11, 6016.

- Lemaire, A.; Limbourg, S. How can food loss and waste management achieve sustainable development goals? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 234, 1221–1234.

- D’Agostin, A.; de Medeiros, J.F.; Vidor, G.; Zulpo, M.; Moretto, C.F. Drivers and barriers for the adoption of use-oriented product-service systems: A study with young consumers in medium and small cities. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 21, 92–103.

- Mangla, S.K.; Luthra, S.; Mishra, N.; Singh, A.; Rana, N.P.; Dora, M.; Dwivedi, Y. Barriers to effective circular supply chain management in a developing country context. Prod. Plan. Control. 2018, 29, 551–569.

- Boschini, M.; Falasconi, L.; Cicatiello, C.; Franco, S. Why the waste? A large-scale study on the causes of food waste at school canteens. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 246, 118994.

- Filimonau, V.; Matute, J.; Kubal-Czerwińska, M.; Krzesiwo, K.; Mika, M. The determinants of consumer engagement in restaurant food waste mitigation in Poland: An exploratory study. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119105.

- Mak, T.M.; Xiong, X.; Tsang, D.C.; Yu, I.K.; Poon, C.S. Sustainable food waste management towards circular bioeconomy: Policy review, limitations and opportunities. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 297, 122497.

- Schiavone, S.; Pelullo, C.P.; Attena, F. Patient Evaluation of Food Waste in Three Hospitals in Southern Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4330.

- Abdelaal, A.H.; McKay, G.; Mackey, H.R. Food waste from a university campus in the Middle East: Drivers, composition, and resource recovery potential. Waste Manag. 2019, 98, 14–20.

- McCarthy, B.; Kapetanaki, A.B.; Wang, P. Circular agri-food approaches: Will consumers buy novel products made from vegetable waste? Rural. Soc. 2019, 28, 91–107.

- Kiefer, C.P.; González, P.D.R.; Carrillo-Hermosilla, J. Drivers and barriers of eco-innovation types for sustainable transitions: A quantitative perspective. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2019, 28, 155–172.

- Camacho-Otero, J.; Boks, C.; Pettersen, I.N. Consumption in the Circular Economy: A Literature Review. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2758.

- Loizia, P.; Neofytou, N.; Zorpas, A.A. The concept of circular economy strategy in food waste management for the optimization of energy production through anaerobic digestion. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 26, 14766–14773.

- Mangialardo, A.; Micelli, E. Rethinking the Construction Industry under the Circular Economy: Principles and Case Studies. In Smart and Sustainable Planning for Cities and Regions; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 333–344.

- Rizos, V.; Behrens, A.; Van Der Gaast, W.; Hofman, E.; Ioannou, A.; Kafyeke, T.; Flamos, A.; Rinaldi, R.; Papadelis, S.; Hirschnitz-Garbers, M.; et al. Implementation of Circular Economy Business Models by Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs): Barriers and Enablers. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1212.

- De Jesus, A.; Mendonça, S. Lost in Transition? Drivers and Barriers in the Eco-innovation Road to the Circular Economy. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 145, 75–89.

- Meghana, M.; Shastri, Y. Sustainable valorization of sugar industry waste: Status, opportunities, and challenges. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 303, 122929.

- Kerdlap, P.; Low, J.S.C.; Ramakrishna, S. Zero waste manufacturing: A framework and review of technology, research, and implementation barriers for enabling a circular economy transition in Singapore. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 151, 104438.

- Ma, Y.; Liu, Y. Turning food waste to energy and resources towards a great environmental and economic sustainability: An innovative integrated biological approach. Biotechnol. Adv. 2019, 37, 107414.

- Van der Werf, P.; Seabrook, J.A.; Gilliland, J. Food for thought: Comparing self-reported versus curbside measurements of household food wasting behavior and the predictive capacity of behavioral determinants. Waste Manag. 2020, 101, 18–27.

- Messner, R.; Richards, C.; Johnson, H. The “Prevention Paradox”: Food waste prevention and the quandary of systemic surplus production. Agric. Hum. Values 2020, 37, 805–817.

- Bravi, L.; Francioni, B.; Murmura, F.; Savelli, E. Factors affecting household food waste among young consumers and actions to prevent it. A comparison among UK, Spain and Italy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 153, 104586.

- García-Herrero, L.; De Menna, F.; Vittuari, M. Food waste at school. The environmental and cost impact of a canteen meal. Waste Manag. 2019, 100, 249–258.

- Ilakovac, B.; Voca, N.; Pezo, L.; Cerjak, M. Quantification and determination of household food waste and its relation to sociodemographic characteristics in Croatia. Waste Manag. 2020, 102, 231–240.

- Kalmykova, Y.; Sadagopan, M.; Rosado, L. Circular economy–From review of theories and practices to development of implementation tools. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 190–201.

- Ghosh, P.R.; Fawcett, D.; Sharma, S.B.; Poinern, G.E.J. Progress towards Sustainable Utilisation and Management of Food Wastes in the Global Economy. Int. J. Food Sci. 2016, 2016, 1–22.

- Irani, Z.; Sharif, A.M. Food security across the enterprise: A puzzle, problem or mess for a circular economy? J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2018, 31, 2–9.

- Cicatiello, C.; Franco, S. Disclosure and assessment of unrecorded food waste at retail stores. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 101932.

- Kuo, T.-C.; Smith, S. A systematic review of technologies involving eco-innovation for enterprises moving towards sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 192, 207–220.

- Liu, Z.; Adams, M.; Walker, T.R. Are exports of recyclables from developed to developing countries waste pollution transfer or part of the global circular economy? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 136, 22–23.

- Zeng, H.; Chen, X.; Xiao, X.; Zhou, Z. Institutional pressures, sustainable supply chain management, and circular economy capability: Empirical evidence from Chinese eco-industrial park firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 155, 54–65.

- De Angelis, R.; Howard, M.; Miemczyk, J. Supply chain management and the circular economy: Towards the circular supply chain. Prod. Plan. Control. 2018, 29, 425–437.

- Salvador, R.; Barros, M.V.; da Luz, L.M.; Piekarski, C.M.; de Francisco, A.C. Circular business models: Current aspects that influence implementation and unaddressed subjects. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 250, 119555.

- Atkins, R.; Deranek, K.; Nonet, G. Supply chain food waste reduction and the triple bottom line. Soc. Bus. 2018, 8, 121–144.

- Liu, J.; Feng, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J. Green supply chain management and the circular economy. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2018, 48, 794–817.

- Janssens, K.; Lambrechts, W.; Van Osch, A.; Semeijn, J. How Consumer Behavior in Daily Food Provisioning Affects Food Waste at Household Level in the Netherlands. Foods 2019, 8, 428.

- Campos, D.A.; Gómez-García, R.; Vilas-Boas, A.A.; Madureira, A.R.; Pintado, M. Management of Fruit Industrial By-Products—A Case Study on Circular Economy Approach. Molecules 2020, 25, 320.

- Walker, P.H.; Seuring, P.S.; Sarkis, J.; Klassen, P.R. Sustainable operations management: Recent trends and future directions. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2014, 34, 1–12.

- Principato, L.; Ruini, L.; Guidi, M.; Secondi, L. Adopting the circular economy approach on food loss and waste: The case of Italian pasta production. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 144, 82–89.

- Horton, P.; Bruce, R.; Reynolds, C.; Milligan, G. Food Chain Inefficiency (FCI): Accounting Conversion Efficiencies Across Entire Food Supply Chains to Re-define Food Loss and Waste. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 3, 79.

- Matharu, A.S.; de Melo, E.M.; Houghton, J.A. Opportunity for high value-added chemicals from food supply chain wastes. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 215, 123–130.

- Wang, X.; Rodrigues, V.S.; Demir, E. Managing Your Supply Chain Pantry: Food Waste Mitigation Through Inventory Control. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2019, 47, 97–102.

- Gokarn, S.; Kuthambalayan, T.S. Analysis of challenges inhibiting the reduction of waste in food supply chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 595–604.

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Morioka, S.; de Carvalho, M.M.; Evans, S. Business models and supply chains for the circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 190, 712–721.

- Irani, Z.; Sharif, A.M. Sustainable food security futures. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2016, 29, 171–178.

- Tostivint, C.; De Veron, S.; Jan, O.; Lanctuit, H.; Hutton, Z.V.; Loubière, M. Measuring food waste in a dairy supply chain in Pakistan. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 145, 221–231.

- Loke, M.K.; Leung, P. Quantifying food waste in Hawaii’s food supply chain. Waste Manag. Res. 2015, 33, 1076–1083.

- Ghisellini, P.; Ulgiati, S. Circular economy transition in Italy. Achievements, perspectives and constraints. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118360.

- Pullman, M.; Maloni, M.J.; Carter, C.R. Food for Thought: Social Versus Environmental Sustainability Practices and Performance Outcomes. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2009, 45, 38–54.

- Homrich, A.S.; Galvão, G.; Abadia, L.G.; Carvalho, M.M. The circular economy umbrella: Trends and gaps on integrating pathways. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 525–543.

- De Ferreira, A.C.; Fuso-Nerini, F. A Framework for Implementing and Tracking Circular Economy in Cities: The Case of Porto. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1813.

- Demichelis, F.; Piovano, F.; Fiore, S. Biowaste Management in Italy: Challenges and Perspectives. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4213.

- Prieto-Sandoval, V.; Jaca, C.; Santos, J.; Baumgartner, R.J.; Ormazabal, M. Key strategies, resources, and capabilities for implementing circular economy in industrial small and medium enterprises. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 1473–1484.

- Vlajic, J.V.; Mijailović, R.; Bogdanova, M. Creating loops with value recovery: Empirical study of fresh food supply chains. Prod. Plan. Control. 2018, 29, 522–538.

- Ingemarsdotter, E.; Jamsin, E.; Balkenende, R. Opportunities and challenges in IoT-enabled circular business model implementation—A case study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 162, 105047.

- Dev, N.K.; Shankar, R.; Qaiser, F.H. Industry 4.0 and circular economy: Operational excellence for sustainable reverse supply chain performance. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 153, 104583.

- Vanderroost, M.; Ragaert, P.; Verwaeren, J.; De Meulenaer, B.; De Baets, B.; Devlieghere, F. The digitization of a food package’s life cycle: Existing and emerging computer systems in the logistics and post-logistics phase. Comput. Ind. 2017, 87, 15–30.

- Hofmann, E.; Rüsch, M. Industry 4.0 and the current status as well as future prospects on logistics. Comput. Ind. 2017, 89, 23–34.

- Haji, M.; Kerbache, L.; Muhammad, M.; Al-Ansari, T. Roles of Technology in Improving Perishable Food Supply Chains. Logistics 2020, 4, 33.

- Hu, F.; Li, L.I.; Liu, Y.; Yan, D. Enhancement of agility in small-lot production environment using 3D printer, industrial robot and machine vision. Int. J. Simul. Syst. Sci. Technol. 2016, 17, 32–37.

- Yu, C.; Xu, X.; Lu, Y. Computer-Integrated Manufacturing, Cyber-Physical Systems and Cloud Manufacturing—Concepts and relationships. Manuf. Lett. 2015, 6, 5–9.

- De Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Godinho-Filho, M.; Roubaud, D. Industry 4.0 and the circular economy: A proposed research agenda and original roadmap for sustainable operations. Ann. Oper. Res. 2018, 270, 273–286.

- Frank, A.G.; Dalenogare, L.G.; Ayala, N.F. Industry 4.0 technologies: Implementation patterns in manufacturing companies. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019, 210, 15–26.

- Rocca, R.; Rosa, P.; Sassanelli, C.; Fumagalli, L.; Terzi, S. Industry 4.0 solutions supporting Circular Economy. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation (ICE/ITMC), Cardiff, UK, 15–17 June 2020; pp. 1–8.

- Alfian, G.; Syafrudin, M.; Farooq, U.; Ma’arif, M.R.; Syaekhoni, M.A.; Fitriyani, N.L.; Rhee, J. Improving efficiency of RFID-based traceability system for perishable food by utilizing IoT sensors and machine learning model. Food Control 2020, 110, 107016.

- Accorsi, R.; Bortolini, M.; Baruffaldi, G.; Pilati, F.; Ferrari, E. Internet-of-things Paradigm in Food Supply Chains Control and Management. Procedia Manuf. 2017, 11, 889–895.

- Singh, A.; Mishra, N.; Ali, S.I.; Shukla, N.; Shankar, R. Cloud computing technology: Reducing carbon footprint in beef supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 164, 462–471.

- Rana, R.L.; Tricase, C.; De Cesare, L. Blockchain technology for a sustainable agri-food supply chain. Br. Food J. 2021.

- Smetana, S.; Aganovic, K.; Heinz, V. Food Supply Chains as Cyber-Physical Systems: A Path for More Sustainable Personalized Nutrition. Food Eng. Rev. 2021, 13, 92–103.

- Sun, J.; Peng, Z.; Yan, L.; Fuh, J.Y.H.; Hong, G.S. 3D food printing—An innovative way of mass customization in food fabrication. Int. J. Bioprinting 2015, 1, 27–38.

- Duong, L.N.; Al-Fadhli, M.; Jagtap, S.; Bader, F.; Martindale, W.; Swainson, M.; Paoli, A. A review of robotics and autonomous systems in the food industry: From the supply chains perspective. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 106, 355–364.

- Kittipanya-Ngam, P.; Tan, K.H. A framework for food supply chain digitalization: Lessons from Thailand. Prod. Plan. Control. 2019, 31, 158–172.

- Duan, J.; Zhang, C.; Gong, Y.; Brown, S.; Li, Z. A Content-Analysis Based Literature Review in Blockchain Adoption within Food Supply Chain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1784.

- Olan, F.; Liu, S.; Suklan, J.; Jayawickrama, U.; Arakpogun, E. The role of Artificial Intelligence networks in sustainable supply chain finance for food and drink industry. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021.

- Kazancoglu, Y.; Pala, M.O.; Sezer, M.D.; Luthra, S.; Kumar, A. Drivers of implementing Big Data Analytics in food supply chains for transition to a circular economy and sustainable operations management. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2021.

- Kumar, S.; Raut, R.D.; Nayal, K.; Kraus, S.; Yadav, V.S.; Narkhede, B.E. To identify industry 4.0 and circular economy adoption barriers in the agriculture supply chain by using ISM-ANP. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 126023.

- Yadav, S.; Luthra, S.; Garg, D. Internet of things (IoT) based coordination system in Agri-food supply chain: Development of an efficient framework using DEMATEL-ISM. Oper. Manag. Res. 2020, 1–27.

- Caro, M.P.; Ali, M.S.; Vecchio, M.; Giaffreda, R. Blockchain-based traceability in Agri-Food supply chain management: A practical implementation. In 2018 IoT Vertical and Topical Summit on Agriculture–Tuscany (IOT Tuscany); Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE): New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–4.

- Annosi, M.C.; Brunetta, F.; Bimbo, F.; Kostoula, M. Digitalization within food supply chains to prevent food waste. Drivers, barriers and collaboration practices. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 93, 208–220.

- Khan, S.A.R.; Yu, Z.; Sarwat, S.; Godil, D.I.; Amin, S.; Shujaat, S. The role of block chain technology in circular economy practices to improve organisational performance. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2021, 1–18.

- Abdella, G.M.; Kucukvar, M.; Onat, N.C.; Al-Yafay, H.M.; Bulak, M.E. Sustainability assessment and modeling based on supervised machine learning techniques: The case for food consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 251, 119661.

- Misra, N.N.; Dixit, Y.; Al-Mallahi, A.; Bhullar, M.S.; Upadhyay, R.; Martynenko, A. IoT, big data and artificial intelligence in agriculture and food industry. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 1.

- Sharma, R.; Kamble, S.S.; Gunasekaran, A.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, A. A systematic literature review on machine learning applications for sustainable agriculture supply chain performance. Comput. Oper. Res. 2020, 119, 104926.

- Halassi, S.; Semeijn, J.; Kiratli, N. From consumer to prosumer: A supply chain revolution in 3D printing. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2019, 49, 200–216.

- Ben-Daya, M.; Hassini, E.; Bahroun, Z.; Banimfreg, B.H. The role of internet of things in food supply chain quality management: A review. Qual. Manag. J. 2021, 28, 17–40.

- Singh, A.; Kumari, S.; Malekpoor, H.; Mishra, N. Big data cloud computing framework for low carbon supplier selection in the beef supply chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 202, 139–149.

- Chen, S.; Liu, X.; Yan, J.; Hu, G.; Shi, Y. Processes, benefits, and challenges for adoption of blockchain technologies in food supply chains: A thematic analysis. Inf. Syst. e-Bus. Manag. 2020, 1–27.

- Jung, J.; Maeda, M.; Chang, A.; Bhandari, M.; Ashapure, A.; Landivar-Bowles, J. The potential of remote sensing and artificial intelligence as tools to improve the resilience of agriculture production systems. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2021, 70, 15–22.

- Liu, P.; Long, Y.; Song, H.-C.; He, Y.-D. Investment decision and coordination of green agri-food supply chain considering information service based on blockchain and big data. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 123646.

- Costa, C.; Antonucci, F.; Pallottino, F.; Aguzzi, J.; Sarriá, D.; Menesatti, P. A Review on Agri-food Supply Chain Traceability by Means of RFID Technology. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2013, 6, 353–366.

- Casino, F.; Kanakaris, V.; Dasaklis, K.T.; Moschuris, S.; Stachtiaris, S.; Pagoni, M.; Rachaniotis, P.N. Block-chain-based food supply chain traceability: A case study in the dairy sector. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020.

- Köhler, S.; Pizzol, M. Technology assessment of blockchain-based technologies in the food supply chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 269, 122193.