Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lindsay Kraus | -- | 2191 | 2023-02-21 14:28:39 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | -2 word(s) | 2189 | 2023-02-22 01:54:46 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Kraus, L.; Beavens, B. Therapeutic Role of Chromatin Remodeling in Heart Failure. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/41485 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Kraus L, Beavens B. Therapeutic Role of Chromatin Remodeling in Heart Failure. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/41485. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Kraus, Lindsay, Brianna Beavens. "Therapeutic Role of Chromatin Remodeling in Heart Failure" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/41485 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Kraus, L., & Beavens, B. (2023, February 21). Therapeutic Role of Chromatin Remodeling in Heart Failure. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/41485

Kraus, Lindsay and Brianna Beavens. "Therapeutic Role of Chromatin Remodeling in Heart Failure." Encyclopedia. Web. 21 February, 2023.

Copy Citation

Cardiovascular diseases are a major cause of death globally, with no cure to date. Many interventions have been studied and suggested, of which epigenetics and chromatin remodeling have been the most promising. Major advancements have been made in the field of chromatin remodeling, particularly for the treatment of heart failure, because of innovations in bioinformatics and gene therapy. Specifically, understanding changes to the chromatin architecture have been shown to alter cardiac disease progression via variations in genomic sequencing, targeting cardiac genes, using RNA molecules, and utilizing chromatin remodeler complexes.

cardiovascular disease

chromatin remodeling

heart failure

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) have been the leading cause of death worldwide for many years [1][2]. It has been estimated that around 17.9 million lives are lost annually due to CVDs across the globe [2]. Currently, there are no cures for any type of CVDs; there are only preventative measures to alleviate risk factors and in extreme cases perform heart transplants [3][4]. CVDs include a multitude of pathological conditions, including atherosclerosis, ischemic heart disease, stroke, and heart failure, to name a few [5]. For this research, heart failure (HF) will be the focus. HF occurs due to structural or functional stress in the heart which no longer allows the heart to properly pump blood and oxygen to designated areas of the body [6][7][8]. This is often manifested in decreased cardiac output and increased internal cardiac pressure [7]. Annually, there are over 64 million cases of HF, accounting for over 346 billion US dollars, and these numbers are projected to rise [9]. It is predicted that the rate of HF will increase by 50% in low and middle sociodemographic regions by 2030 [9]. With no cure and increasing concern across the globe, there is a dire need to understand and treat this devastating disease.

Because of the lack of a cure for HF, many interventions have been utilized to attenuate risk factors. There is an assembly of drug-based interventions that have proven to be instrumental in treating the risk factors associated with HF, one of the most significant being chronic hypertension [10]. Heart transplants do occur, but not as frequently as they are needed [11]. To truly cure an injured heart, cardiac stem cells have been suggested and are currently being studied [12]. However, they have not been as successful as originally proposed due to engraftment issues and detrimental immune responses [13]. Alternatively, cardiac remodeling via epigenetic regulation has been studied and has had promising outcomes [14]. In recent research, the combination of epigenetic regulated chromatin remodeling methods with the techniques, advancements, and theories of stem cell regulation have been groundbreaking for the field of cardiac biology [15][16].

The role of chromatin remodeling in HF is not a new idea, partially due to the overwhelming application of epigenetics in cardiac biology [14][17][18][19]. Generally, it is believed that when epigenetic modifications are altered there is a progression or suppression of the cardiac disease state [20]. Normally, eukaryotic DNA is tightly condensed in chromatin, which is compacted around histones that form a nucleosome [21]. These histones have all been identified (H1, H2A, H2B, H3, H4) and are well understood in cardiac biology [22][23][24]. However, changes to these histones and the chromatin are less understood. Modifications such as a methylation and phosphorylation can be added to or removed from these structures, altering the chromatin architecture as well as the recruitment of complexes that can alter the overall chromatin structure [25]. These alterations dictate whether the DNA becomes more or less tightly condensed. The more compacted the DNA, the less available the genes, meaning less gene expression or transcription.

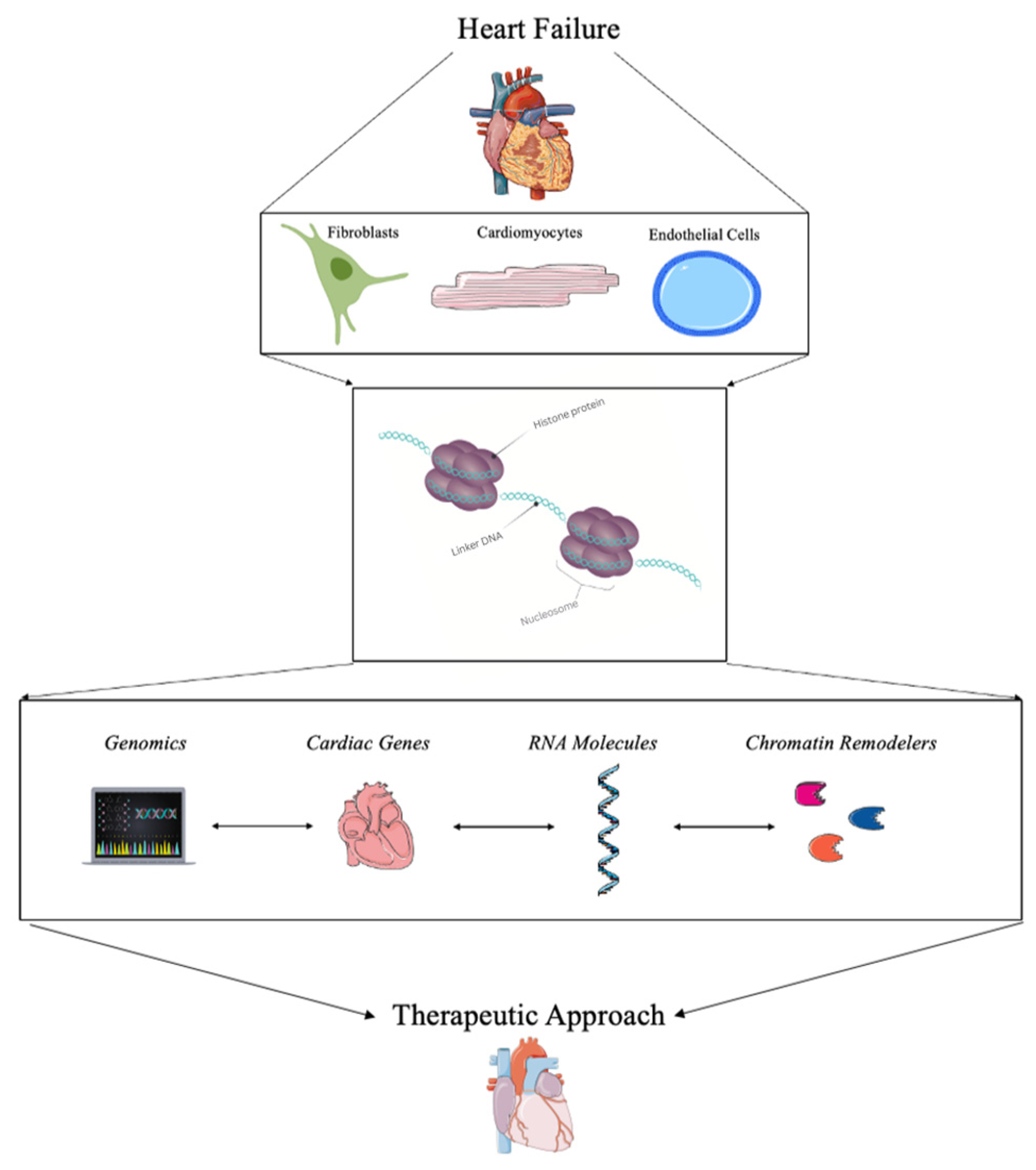

Targeting the changes in chromatin architecture or chromatin remodeling has been of interest over the past few years. With promising strategies, potential clinical trials, and the advancement of therapeutic approaches, chromatin remodeling in HF is a vital method for understanding this devasting disease to find a therapeutic approach to treating HF as depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Summary of the role of chromatin remodeling for the treatment of heart failure.

2. Current Strategies for Detecting Chromatin Remodeling in Heart Failure

With advancements in bioinformatics as well as gene therapy technology, the ability to study chromatin as a clinical cardiac therapeutic has greatly increased over the last decade [26][27][28][29][30]. Because chromatin is often tightly compacted and densely organized in the nucleus of cells, it can be difficult to isolate [31]. Importantly, variations to the chromatin architecture are a three-dimensional, multifaceted challenge for researchers [18]. To truly find a therapeutic approach, it is important to know the current challenges and new advancements in studying chromatin remodeling in the heart. Currently, there are standard approaches to studying changes in chromatin remodeling and gene expression due to changes in epigenetic profiles [32][33][34]. Many of these approaches include a combination of genomics, RNA molecules, cardiac gene targets, and chromatin remodelers. Advancements in bioinformatics and gene therapy have proven to be pivotal in understanding pathological signaling in cardiac disease states; however, this can prove challenging and too broad for a true therapeutic approach. Additionally, targeting only a specific change in selective gene expression can be difficult and can cause other adverse downstream effects as well [35]. However, a combination of all of these advancements could provide information to build a comprehensive understanding of chromatin remodeling during HF.

A more recent and promising strategy is using small molecules to target chromatin remodeling in the heart. By using chromatin remodeling enzymes, histone modifiers, chromatin regulatory complexes, and even DNA modifiers, the changes in chromatin architecture can be directly studied. This has been shown with the Switch/Sucrose-Nonfermentable (SWI/SNF) chromatin remodeling complex in many oncological studies, but it could also prove valuable in the heart [36]. Similarly, small molecules such as long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) have been used to assess chromatin remodeling [37]. The lncRNAs have been directly associated with structural changes in the chromatin in many disease models, including during pathological challenges to the heart [38][39]. One of the biggest advancements for understanding chromatin remodeling during HF is through genetic profiling approaches via sequencing and bioinformatic-based analysis. Using ATAC sequencing, RNA sequencing, and ChIP sequencing has led to major advancements in understanding epigenetic changes during HF. Specifically, for chromatin remodeling, combining these approaches in a novel “multiomic” approach has led to major discoveries that will be addressed here.

3. Therapeutic Approaches Using Chromatin Remodeling in Heart Failure

3.1. Genomics and Bioinformatics

The use of genomics to understand chromatin alterations and all the downstream changes has become a steadfast approach to most clinical applications of HF research. Many genomics-based research techniques are incorporated into most current studies along with other techniques, as this research will highlight. It is important to emphasize some of the most influential sequencing techniques that have made an impact on the field of chromatin remodeling in cardiac biology. One of the main methods to study chromatin remodeling through genomics is through the Assay for Transposase Accessible Chromatin (ATAC) sequencing. This ATAC sequencing data allows researchers to understand chromatin remodeling, chromatin accessibility, and epigenetic profiles [34]. Through this sequencing method, studies have found pivotal transcriptional and chromatin accessibility differences in HF [40]. For example, one study used ATAC sequencing to understand trans-aortic constriction in mice and found predictors of chromatin structural changes that led to a pivotal understanding of gene expression changes during disease progression [41]. Another study used ATAC sequencing to analyze different genes found in hypoxia-induced stress associated with HF and found major changes in the chromatin’s accessibility during stress [42]. ATAC sequencing is often paired with other genomic techniques or gene expression data.

Many of the widely used techniques include ATAC sequencing, RNA sequencing, miRNA sequencing, and DNA sequencing. All of these are not new techniques; however, how the data is used and interpreted is constantly changing. For example, one study used the multiomic approach, meaning they used single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA seq), single-cell ATAC (scATAC seq), bulk ATAC sequencing, and miRNA sequencing to study HF in murine models [43]. From these immense data sets, the authors found miRNA expression differences that aligned with chromatin accessibility profiles in mice with HF that were not seen in the control mice. All of this gave a new understanding of potential targets and mechanisms in the progression of HF [43].

3.2. Targeting Cardiac Genes for Transcriptional Regulation

Chromatin remodeling in the heart is regulated by a multitude of genes. Some of these cardiac genes have been targeted during HF to assess changes in the cardiac disease state. For example, the transcription factor, Med1, was found to regulate chromatin remodeling in cardiomyocytes. Specifically, Med1 was found to synchronize the histone acetylation of lysine 27 (H3K27) which allowed for more open chromatin accessibility and therefore more gene expression [44]. One study found that changes in gene expression in GATA4 and NXK2.5 were associated with changes in the chromatin architecture [41]. Interestingly, the authors found a decrease in the protein CTCF, which is a chromatin structural protein, specifically after HF in murine cardiomyocytes [41]. Likewise, another study found that GATA4 plays a major role in the chromatin structure, specifically in cardiac disease progression as well as cardiac development [45].

It has also been found that changes in chromatin architecture have a role in cardiac fibroblast phenotypic gene expression. After cardiac injury, there is often an influx of cardiac fibroblasts that form scar tissue in the heart. Too much fibrosis can lead to irreversible damage and decreased heart function [46]. It has been suggested that transcription factors such as GATA4, as well as MEF2C and TBX5, could be directly reprogrammed to alter their chromatin remodeling and therefore epigenetic signaling in fibrosis [47][48]. This has specifically been studied in cardiac fibroblasts in vitro and in vivo with high success [49][50][51][52][53]. Additionally, changes in chromatic structure were shown to affect the stiffness of cardiac fibroblasts after injury [54]. It was also found that topological change to cardiac fibroblasts significantly altered the chromatin remodeling and downstream cardiac gene expression associated with a decreased pathological response [55]. The chromatin remodeling protein, BRG1, was also found to be a vital regulator of cardiac fibrosis, specifically in regulating the endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition [56].

3.3. RNA Molecules

The use of small RNA molecules, often deemed non-coding RNA molecules, has been of great interest in epigenetic regulation and chromatin remodeling, specifically in HF [57]. Many RNA molecules have been studied in pathological cardiac models, microRNAs (miRNAs), circular RNA (circRNA), and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) being the primary focus due to influential and novel data [58][59][60][61].

It has been shown that the lncRNAs are regulated by ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling factors in both mouse and human hearts during HF [37]. The lncRNAs have also been used as biomarkers for HF [58][59]. Current research has indicated that these lncRNAs may be the master regulators of disease progression in HF via chromatin remodeling [62][63][64]. Many lncRNA can bind and regulate chromatin remodeling through epigenetic modifications and therefore regulate various cardiac gene expression levels during pathological stress [55][61].

The circular RNAs (circRNA) have also been of interest due to their ability to act as a sponge as well as a transcriptional regulator throughout cardiac tissue [65]. Because of their unique role in cardiac tissue, circRNAs have been proposed as major biomarkers for HF [66]. For example, one study found that the circRNA named circNCX1 played a major role in cardiomyocyte death during cardiac injury. Specifically, there was an increase in this circNCX1 with an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS). The knockdown of this circRNA decreased the amount of cardiomyocyte cell death in mouse hearts [67]. Often circRNAs do not act completely alone. One study found that the circRNA circ-HIPK3 interacted with the miRNA miR-17-3p to regulate calcium signaling during HF. Specifically, the downregulation of the circRNA seemed to lessen the fibrotic response and the progression of HF in adult mice [68].

3.4. Chromatin Remodelers and Complexes

Unlike RNA molecules and cardiac gene transcription, chromatin remodelers play a direct role in regulating chromatin architecture. When the chromatin remodelers are dysregulated, the chromatin structure is altered, which can lead to devasting pathological responses that cause increased cardiac cell death, inflammatory signaling, and stress responses found in HF [38]. One study found that the chromatin remodeling protein BRG1 and p300 had stage-specific regulation of histone acetylation. Specifically, these chromatin remodelers were upregulated during HF but not during left ventricular hypertrophy, indicating a step-wise transition regulated by chromatin regulators [69]. The chromatin regulator, identified as SETD7, known for the methylation of histone 3 at lysine 4 (H3K4me1), was found to regulate inflammation pathways in obese patients with HF [70]. It was found that the loss of SETD7 in murine cardiomyocytes protected against hypertrophy and further cardiac dysfunction that was directly associated with the regulation of inflammatory genes [70]. Another study found that the interaction between a histone lysine methyltransferase named G9a and its downstream target Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) regulated histone epigenetic modifications, therefore altering chromatin remodeling. It was found that G9a, which inhibits BDNF and increases cardiomyocyte death, is overexpressed in HF [71]. Another study found that ZNHIT1, a major regulator of a chromatin remodeling complex, was necessary for heart function [72]. Specifically, the loss of this chromatin regulator caused rapid HF and dysregulated calcium signaling. It was determined that the ZNHIT1 regulated CASQ1, a major regulator of calcium signaling in the sarcoplasmic reticulum, by altering the histone 2A variant and therefore chromatin regulation [72]. It was also found that BAF60c, a chromatin remodeling complex also called SMARCD3, regulates cardiomyocyte growth through MEF2 and myocardin gene expression [73].

References

- Mc Namara, K.; Alzubaidi, H.; Jackson, J.K. Cardiovascular disease as a leading cause of death: How are pharmacists getting involved? Integr. Pharm. Res. Pract. 2019, 8, 1–11.

- Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) (accessed on 17 February 2020).

- Ciumărnean, L.; Milaciu, M.V.; Negrean, V.; Orășan, O.H.; Vesa, S.C.; Sălăgean, O.; Iluţ, S.; Vlaicu, S.I. Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Physical Activity for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Diseases in the Elderly. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 207.

- Lifestyle Strategies for Risk Factor Reduction, Prevention and Treatme. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.1201/9781315201108-2/lifestyle-strategies-risk-factor-reduction-prevention-treatment-cardiovascular-disease-james-rippe-theodore-angelopoulos (accessed on 6 January 2023).

- Zhao, D.; Liu, J.; Wang, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, M. Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in China: Current features and implications. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2019, 16, 203–212.

- Savarese, G.; Lund, L.H. Global Public Health Burden of Heart Failure. Card. Fail. Rev. 2017, 3, 7–11.

- Kurmani, S.; Squire, I. Acute Heart Failure: Definition, Classification and Epidemiology. Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 2017, 14, 385–392.

- CDC Heart Failure|cdc.gov. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 8 September 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/heartdisease/heart_failure.htm (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- Lippi, G.; Sanchis-Gomar, F. Global epidemiology and future trends of heart failure. AME Med. J. 2020, 5, 1–6.

- Rossignol, P.; Hernandez, A.F.; Solomon, S.D.; Zannad, F. Heart failure drug treatment. Lancet 2019, 393, 1034–1044.

- Smits, J.M.; Samuel, U.; Laufer, G. Bridging the gap in heart transplantation. Curr. Opin. Organ. Transplant. 2017, 22, 221–224.

- Rheault-Henry, M.; White, I.; Grover, D.; Atoui, R. Stem cell therapy for heart failure: Medical breakthrough, or dead end? World J. Stem Cells 2021, 13, 236–259.

- Segers, V.F.M.; Lee, R.T. Stem-cell therapy for cardiac disease. Nature 2008, 451, 937–942.

- Alexanian, M.; Padmanabhan, A.; McKinsey, T.A.; Haldar, S.M. Epigenetic therapies in heart failure. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2019, 130, 197–204.

- Kim, S.Y.; Morales, C.; Gillette, T.G.; Hill, J.A. Epigenetic Regulation in Heart Failure. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2016, 31, 255–265.

- Chaturvedi, P.; Tyagi, S.C. Epigenetic mechanisms underlying cardiac degeneration and regeneration. Int. J. Cardiol. 2014, 173, 1–11.

- Liu, C.-F.; Tang, W.H.W. Epigenetics in Cardiac Hypertrophy and Heart Failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. Basic Trans. Sci. 2019, 4, 976–993.

- McKinsey, T.A.; Vondriska, T.M.; Wang, Y. Epigenomic regulation of heart failure: Integrating histone marks, long noncoding RNAs, and chromatin architecture. F1000Res 2018, 7, F1000.

- Kimball, T.H.; Vondriska, T.M. Metabolism, Epigenetics, and Causal Inference in Heart Failure. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 31, 181–191.

- Shi, Y.; Zhang, H.; Huang, S.; Yin, L.; Wang, F.; Luo, P.; Huang, H. Epigenetic regulation in cardiovascular disease: Mechanisms and advances in clinical trials. Sig. Transduct. Target. 2022, 7, 200.

- McGinty, R.K.; Tan, S. Histone, Nucleosome, and Chromatin Structure. In Fundamentals of Chromatin; Workman, J.L., Abmayr, S.M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1–28. ISBN 978-1-4614-8624-4.

- Shah, M.; He, Z.; Rauf, A.; Beikoghli Kalkhoran, S.; Heiestad, C.M.; Stensløkken, K.-O.; Parish, C.R.; Soehnlein, O.; Arjun, S.; Davidson, S.M.; et al. Extracellular histones are a target in myocardial ischaemia–reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc. Res. 2021, 118, 1115–1125.

- Gilsbach, R.; Schwaderer, M.; Preissl, S.; Grüning, B.A.; Kranzhöfer, D.; Schneider, P.; Nührenberg, T.G.; Mulero-Navarro, S.; Weichenhan, D.; Braun, C.; et al. Distinct epigenetic programs regulate cardiac myocyte development and disease in the human heart in vivo. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 391.

- Zhang, Q.-J.; Liu, Z.-P. Histone methylations in heart development, congenital and adult heart diseases. Epigenomics 2015, 7, 321–330.

- Bannister, A.J.; Kouzarides, T. Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications. Cell Res. 2011, 21, 381–395.

- Lorch, Y.; Maier-Davis, B.; Kornberg, R.D. Mechanism of chromatin remodeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 3458–3462.

- Chromatin Remodeling in Eukaryotes|Learn Science at Scitable. Available online: http://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/chromatin-remodeling-in-eukaryotes-1082 (accessed on 6 January 2023).

- Pasipoularides, A. Implementing genome-driven personalized cardiology in clinical practice. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2018, 115, 142–157.

- Khomtchouk, B.B.; Tran, D.-T.; Vand, K.A.; Might, M.; Gozani, O.; Assimes, T.L. Cardioinformatics: The nexus of bioinformatics and precision cardiology. Brief. Bioinform. 2020, 21, 2031–2051.

- Hunt, C.; Montgomery, S.; Berkenpas, J.W.; Sigafoos, N.; Oakley, J.C.; Espinosa, J.; Justice, N.; Kishaba, K.; Hippe, K.; Si, D.; et al. Recent Progress of Machine Learning in Gene Therapy. Curr. Gene Ther. 2022, 22, 132–143.

- Tsompana, M.; Buck, M.J. Chromatin accessibility: A window into the genome. Epigenet. Chromatin 2014, 7, 33.

- Xu, W.; Wen, Y.; Liang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Wang, X.; Jin, W.; Chen, X. A plate-based single-cell ATAC-seq workflow for fast and robust profiling of chromatin accessibility. Nat. Protoc. 2021, 16, 4084–4107.

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Kollipara, R.K.; Orquera-Tornakian, G.; Goetsch, S.; Zhang, M.; Perry, C.; Li, B.; Shelton, J.M.; Bhakta, M.; Duan, J.; et al. Global chromatin landscapes identify candidate noncoding modifiers of cardiac rhythm. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 133, 3.

- Jia, G.; Preussner, J.; Chen, X.; Guenther, S.; Yuan, X.; Yekelchyk, M.; Kuenne, C.; Looso, M.; Zhou, Y.; Teichmann, S.; et al. Single cell RNA-seq and ATAC-seq analysis of cardiac progenitor cell transition states and lineage settlement. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4877.

- McKinsey, T.A.; Olson, E.N. Toward transcriptional therapies for the failing heart: Chemical screens to modulate genes. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 538–546.

- Centore, R.C.; Sandoval, G.J.; Soares, L.M.M.; Kadoch, C.; Chan, H.M. Mammalian SWI/SNF Chromatin Remodeling Complexes: Emerging Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. Trends Genet. 2020, 36, 936–950.

- Han, P.; Chang, C.-P. Long non-coding RNA and chromatin remodeling. RNA Biol. 2015, 12, 1094–1098.

- Han, P.; Yang, J.; Shang, C.; Chang, C.-P. Chromatin Remodeling in Heart Failure. In Epigenetics in Cardiac Disease; Backs, J., McKinsey, T.A., Eds.; Cardiac and Vascullar Biology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 103–124. ISBN 978-3-319-41457-7.

- Han, P.; Li, W.; Lin, C.-H.; Yang, J.; Shang, C.; Nuernberg, S.T.; Jin, K.K.; Xu, W.; Lin, C.-Y.; Lin, C.-J.; et al. A long noncoding RNA protects the heart from pathological hypertrophy. Nature 2014, 514, 102–106.

- Kuppe, C.; Ramirez Flores, R.O.; Li, Z.; Hayat, S.; Levinson, R.T.; Liao, X.; Hannani, M.T.; Tanevski, J.; Wünnemann, F.; Nagai, J.S.; et al. Spatial multi-omic map of human myocardial infarction. Nature 2022, 608, 766–777.

- Chapski, D.J.; Cabaj, M.; Morselli, M.; Mason, R.J.; Soehalim, E.; Ren, S.; Pellegrini, M.; Wang, Y.; Vondriska, T.M.; Rosa-Garrido, M. Early adaptive chromatin remodeling events precede pathologic phenotypes and are reinforced in the failing heart. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2021, 160, 73–86.

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Duan, Z.; Hu, W. Hypoxia-induced alterations of transcriptome and chromatin accessibility in HL-1 cells. IUBMB Life 2020, 72, 1737–1746.

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, H. A multi-omics approach to identify molecular alterations in a mouse model of heart failure. Theranostics 2022, 12, 1607–1620.

- Hall, D.D.; Spitler, K.M.; Grueter, C.E. Disruption of cardiac Med1 inhibits RNA polymerase II promoter occupancy and promotes chromatin remodeling. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2019, 316, H314–H325.

- He, A.; Gu, F.; Hu, Y.; Ma, Q.; Yi Ye, L.; Akiyama, J.A.; Visel, A.; Pennacchio, L.A.; Pu, W.T. Dynamic GATA4 enhancers shape the chromatin landscape central to heart development and disease. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4907.

- Jiang, W.; Xiong, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, Y. Cardiac Fibrosis: Cellular Effectors, Molecular Pathways, and Exosomal Roles. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 715258.

- Beisaw, A.; Kuenne, C.; Guenther, S.; Dallmann, J.; Wu, C.-C.; Bentsen, M.; Looso, M.; Stainier, D.Y.R. AP-1 Contributes to Chromatin Accessibility to Promote Sarcomere Disassembly and Cardiomyocyte Protrusion During Zebrafish Heart Regeneration. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 1760–1778.

- de Pater, E.; Clijsters, L.; Marques, S.R.; Lin, Y.-F.; Garavito-Aguilar, Z.V.; Yelon, D.; Bakkers, J. Distinct phases of cardiomyocyte differentiation regulate growth of the zebrafish heart. Development 2009, 136, 1633–1641.

- Mathison, M.; Singh, V.P.; Sanagasetti, D.; Yang, L.; Pinnamaneni, J.P.; Yang, J.; Rosengart, T.K. Cardiac Reprogramming Factor Gata4 Reduces Post-Infarct Cardiac Fibrosis through Direct Repression of the Pro-Fibrotic Mediator Snail. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2017, 154, 1601–1610.

- Ieda, M. Key Regulators of Cardiovascular Differentiation and Regeneration: Harnessing the Potential of Direct Reprogramming to Treat Heart Failure. J. Card. Fail. 2020, 26, 80–84.

- Yamakawa, H.; Ieda, M. Cardiac regeneration by direct reprogramming in this decade and beyond. Inflamm. Regen. 2021, 41, 20.

- McKinsey, T.A.; Foo, R.; Anene-Nzelu, C.G.; Travers, J.G.; Vagnozzi, R.J.; Weber, N.; Thum, T. Emerging epigenetic therapies of cardiac fibrosis and remodeling in heart failure: From basic mechanisms to early clinical development. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 118, cvac142.

- Chen, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, Z.-A.; Shen, Z. Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into cardiomyocytes. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2017, 8, 118.

- Hu, S.; Vondriska, T.M. How chromatin stiffens fibroblasts. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2022, 26, 100537.

- Yu, J.; Seldin, M.M.; Fu, K.; Li, S.; Lam, L.; Wang, P.; Wang, Y.; Huang, D.; Nguyen, T.L.; Wei, B.; et al. Topological Arrangement of Cardiac Fibroblasts Regulates Cellular Plasticity. Circ. Res. 2018, 123, 73–85.

- Li, Z.; Kong, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, L.; Guo, J.; Xu, Y. Dual roles of chromatin remodeling protein BRG1 in angiotensin II-induced endothelial–mesenchymal transition. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 549.

- Lu, P.; Ding, F.; Xiang, Y.K.; Hao, L.; Zhao, M. Noncoding RNAs in Cardiac Hypertrophy and Heart Failure. Cells 2022, 11, 777.

- Li, M.; Duan, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, B. Long noncoding RNA/circular noncoding RNA–miRNA–mRNA axes in cardiovascular diseases. Life Sci. 2019, 233, 116440.

- Gong, C.; Zhou, X.; Lai, S.; Wang, L.; Liu, J. Long Noncoding RNA/Circular RNA-miRNA-mRNA Axes in Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 8838524.

- Chen, Y.-H.; Zhong, L.-F.; Hong, X.; Zhu, Q.-L.; Wang, S.-J.; Han, J.-B.; Huang, W.-J.; Ye, B.-Z. Integrated Analysis of circRNA-miRNA-mRNA ceRNA Network in Cardiac Hypertrophy. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 123.

- Zhang, G.; Dou, L.; Chen, Y. Association of long-chain non-coding RNA MHRT gene single nucleotide polymorphism with risk and prognosis of chronic heart failure. Medicine 2020, 99, e19703.

- Hobuß, L.; Bär, C.; Thum, T. Long Non-coding RNAs: At the Heart of Cardiac Dysfunction? Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 30.

- Zhang, Z.; Wan, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, W. Strategies and technologies for exploring long noncoding RNAs in heart failure. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 131, 110572.

- Hermans-Beijnsberger, S.; van Bilsen, M.; Schroen, B. Long non-coding RNAs in the failing heart and vasculature. Noncoding RNA Res. 2018, 3, 118–130.

- Tan, W.L.W.; Lim, B.T.S.; Anene-Nzelu, C.G.O.; Ackers-Johnson, M.; Dashi, A.; See, K.; Tiang, Z.; Lee, D.P.; Chua, W.W.; Luu, T.D.A.; et al. A landscape of circular RNA expression in the human heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 2017, 113, 298–309.

- Sun, C.; Ni, M.; Song, B.; Cao, L. Circulating Circular RNAs: Novel Biomarkers for Heart Failure. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 560537.

- Li, M.; Ding, W.; Tariq, M.A.; Chang, W.; Zhang, X.; Xu, W.; Hou, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J. A circular transcript of ncx1 gene mediates ischemic myocardial injury by targeting miR-133a-3p. Theranostics 2018, 8, 5855–5869.

- Deng, Y.; Wang, J.; Xie, G.; Zeng, X.; Li, H. Circ-HIPK3 Strengthens the Effects of Adrenaline in Heart Failure by MiR-17-3p-ADCY6 Axis. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 15, 2484–2496.

- Funamoto, M.; Sunagawa, Y.; Katanasaka, Y.; Shimizu, K.; Miyazaki, Y.; Sari, N.; Shimizu, S.; Mori, K.; Wada, H.; Hasegawa, K.; et al. Histone Acetylation Domains Are Differentially Induced during Development of Heart Failure in Dahl Salt-Sensitive Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1771.

- Costantino, S.; Ambrosini, S.; Mohammed, S.A.; Gorica, E.; Akhmedov, A.; Cosentino, F.; Ruschitzka, F.; Hamdani, N.; Paneni, F. A chromatin mark by SETD7 regulates myocardial inflammation in obesity-related heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, ehac544.2883.

- Yan, F.; Chen, Z.; Cui, W. H3K9me2 regulation of BDNF expression via G9a partakes in the progression of heart failure. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2022, 22, 182.

- Shi, Y.; Fan, W.; Xu, M.; Lin, X.; Zhao, W.; Yang, Z. Critical role of Znhit1 for postnatal heart function and vacuolar cardiomyopathy. JCI Insight 2022, 7, e148752.

- Sun, X.; Hota, S.K.; Zhou, Y.-Q.; Novak, S.; Miguel-Perez, D.; Christodoulou, D.; Seidman, C.E.; Seidman, J.G.; Gregorio, C.C.; Henkelman, R.M.; et al. Cardiac-enriched BAF chromatin-remodeling complex subunit Baf60c regulates gene expression programs essential for heart development and function. Biol. Open 2018, 7, bio029512.

More

Information

Subjects:

Cell Biology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

758

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

22 Feb 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No