| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vivi Li | -- | 4269 | 2022-11-11 01:39:29 |

Video Upload Options

In probability theory and statistics, the chi-square distribution (also chi-squared or χ2-distribution) with k degrees of freedom is the distribution of a sum of the squares of k independent standard normal random variables. The chi-square distribution is a special case of the gamma distribution and is one of the most widely used probability distributions in inferential statistics, notably in hypothesis testing and in construction of confidence intervals. This distribution is sometimes called the central chi-square distribution, a special case of the more general noncentral chi-square distribution. The chi-square distribution is used in the common chi-square tests for goodness of fit of an observed distribution to a theoretical one, the independence of two criteria of classification of qualitative data, and in confidence interval estimation for a population standard deviation of a normal distribution from a sample standard deviation. Many other statistical tests also use this distribution, such as Friedman's analysis of variance by ranks.

1. Definitions

If Z1, ..., Zk are independent, standard normal random variables, then the sum of their squares,

- [math]\displaystyle{ Q\ = \sum_{i=1}^k Z_i^2 , }[/math]

is distributed according to the chi-square distribution with k degrees of freedom. This is usually denoted as

- [math]\displaystyle{ Q\ \sim\ \chi^2(k)\ \ \text{or}\ \ Q\ \sim\ \chi^2_k . }[/math]

The chi-square distribution has one parameter: a positive integer k that specifies the number of degrees of freedom (the number of random variables being summed, Zi s).

1.1. Introduction

The chi-square distribution is used primarily in hypothesis testing, and to a lesser extent for confidence intervals for population variance when the underlying distribution is normal. Unlike more widely known distributions such as the normal distribution and the exponential distribution, the chi-square distribution is not as often applied in the direct modeling of natural phenomena. It arises in the following hypothesis tests, among others:

- Chi-square test of independence in contingency tables

- Chi-square test of goodness of fit of observed data to hypothetical distributions

- Likelihood-ratio test for nested models

- Log-rank test in survival analysis

- Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test for stratified contingency tables

It is also a component of the definition of the t-distribution and the F-distribution used in t-tests, analysis of variance, and regression analysis.

The primary reason for which the chi-square distribution is extensively used in hypothesis testing is its relationship to the normal distribution. Many hypothesis tests use a test statistic, such as the t-statistic in a t-test. For these hypothesis tests, as the sample size, n, increases, the sampling distribution of the test statistic approaches the normal distribution (central limit theorem). Because the test statistic (such as t) is asymptotically normally distributed, provided the sample size is sufficiently large, the distribution used for hypothesis testing may be approximated by a normal distribution. Testing hypotheses using a normal distribution is well understood and relatively easy. The simplest chi-square distribution is the square of a standard normal distribution. So wherever a normal distribution could be used for a hypothesis test, a chi-square distribution could be used.

Suppose that [math]\displaystyle{ Z }[/math] is a random variable sampled from the standard normal distribution, where the mean is [math]\displaystyle{ 0 }[/math] and the variance is [math]\displaystyle{ 1 }[/math]: [math]\displaystyle{ Z \sim N(0,1) }[/math]. Now, consider the random variable [math]\displaystyle{ Q = Z^2 }[/math]. The distribution of the random variable [math]\displaystyle{ Q }[/math] is an example of a chi-square distribution: [math]\displaystyle{ \ Q\ \sim\ \chi^2_1 . }[/math] The subscript 1 indicates that this particular chi-square distribution is constructed from only 1 standard normal distribution. A chi-square distribution constructed by squaring a single standard normal distribution is said to have 1 degree of freedom. Thus, as the sample size for a hypothesis test increases, the distribution of the test statistic approaches a normal distribution. Just as extreme values of the normal distribution have low probability (and give small p-values), extreme values of the chi-square distribution have low probability.

An additional reason that the chi-square distribution is widely used is that it turns up as the large sample distribution of generalized likelihood ratio tests (LRT).[1] LRT's have several desirable properties; in particular, simple LRT's commonly provide the highest power to reject the null hypothesis (Neyman–Pearson lemma) and this leads also to optimality properties of generalised LRTs. However, the normal and chi-square approximations are only valid asymptotically. For this reason, it is preferable to use the t distribution rather than the normal approximation or the chi-square approximation for a small sample size. Similarly, in analyses of contingency tables, the chi-square approximation will be poor for a small sample size, and it is preferable to use Fisher's exact test. Ramsey shows that the exact binomial test is always more powerful than the normal approximation.[2]

Lancaster shows the connections among the binomial, normal, and chi-square distributions, as follows.[3] De Moivre and Laplace established that a binomial distribution could be approximated by a normal distribution. Specifically they showed the asymptotic normality of the random variable

- [math]\displaystyle{ \chi = {m - Np \over \sqrt{Npq}} }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] is the observed number of successes in [math]\displaystyle{ N }[/math] trials, where the probability of success is [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math], and [math]\displaystyle{ q = 1 - p }[/math].

Squaring both sides of the equation gives

- [math]\displaystyle{ \chi^2 = {(m - Np)^2\over Npq} }[/math]

Using [math]\displaystyle{ N = Np + N(1 - p) }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ N = m + (N - m) }[/math], and [math]\displaystyle{ q = 1 - p }[/math], this equation can be rewritten as

- [math]\displaystyle{ \chi^2 = {(m - Np)^2\over Np} + {(N - m - Nq)^2\over Nq} }[/math]

The expression on the right is of the form that Karl Pearson would generalize to the form:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \chi^2 = \sum_{i=1}^n \frac{(O_i - E_i)^2}{E_i} }[/math]

where

- [math]\displaystyle{ \chi^2 }[/math] = Pearson's cumulative test statistic, which asymptotically approaches a [math]\displaystyle{ \chi^2 }[/math] distribution.

- [math]\displaystyle{ O_i }[/math] = the number of observations of type [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math].

- [math]\displaystyle{ E_i = N p_i }[/math] = the expected (theoretical) frequency of type [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math], asserted by the null hypothesis that the fraction of type [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] in the population is [math]\displaystyle{ p_i }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] = the number of cells in the table.

In the case of a binomial outcome (flipping a coin), the binomial distribution may be approximated by a normal distribution (for sufficiently large [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]). Because the square of a standard normal distribution is the chi-square distribution with one degree of freedom, the probability of a result such as 1 heads in 10 trials can be approximated either by using the normal distribution directly, or the chi-square distribution for the normalised, squared difference between observed and expected value. However, many problems involve more than the two possible outcomes of a binomial, and instead require 3 or more categories, which leads to the multinomial distribution. Just as de Moivre and Laplace sought for and found the normal approximation to the binomial, Pearson sought for and found a degenerate multivariate normal approximation to the multinomial distribution (the numbers in each category add up to the total sample size, which is considered fixed). Pearson showed that the chi-square distribution arose from such a multivariate normal approximation to the multinomial distribution, taking careful account of the statistical dependence (negative correlations) between numbers of observations in different categories. [3]

1.2. Probability Density Function

The probability density function (pdf) of the chi-square distribution is

- [math]\displaystyle{ f(x;\,k) = \begin{cases} \dfrac{x^{\frac k 2 -1} e^{-\frac x 2}}{2^{\frac k 2} \Gamma\left(\frac k 2 \right)}, & x \gt 0; \\ 0, & \text{otherwise}. \end{cases} }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \Gamma(k/2) }[/math] denotes the gamma function, which has closed-form values for integer [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math].

For derivations of the pdf in the cases of one, two and [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] degrees of freedom, see Proofs related to chi-square distribution.

1.3. Cumulative Distribution Function

Its cumulative distribution function is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ F(x;\,k) = \frac{\gamma(\frac{k}{2},\,\frac{x}{2})}{\Gamma(\frac{k}{2})} = P\left(\frac{k}{2},\,\frac{x}{2}\right), }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma(s,t) }[/math] is the lower incomplete gamma function and [math]\displaystyle{ P(s,t) }[/math] is the regularized gamma function.

In a special case of [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] = 2 this function has the simple form:

- [math]\displaystyle{ F(x;\,2) = 1 - e^{-x/2} }[/math]

which can be easily derived by integrating [math]\displaystyle{ f(x;\,2)=\frac{1}{2}e^{-\frac{x}{2}} }[/math] directly. The integer recurrence of the gamma function makes it easy to compute [math]\displaystyle{ F(x;\,2) }[/math] for other small, even [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math].

Tables of the chi-square cumulative distribution function are widely available and the function is included in many spreadsheets and all statistical packages.

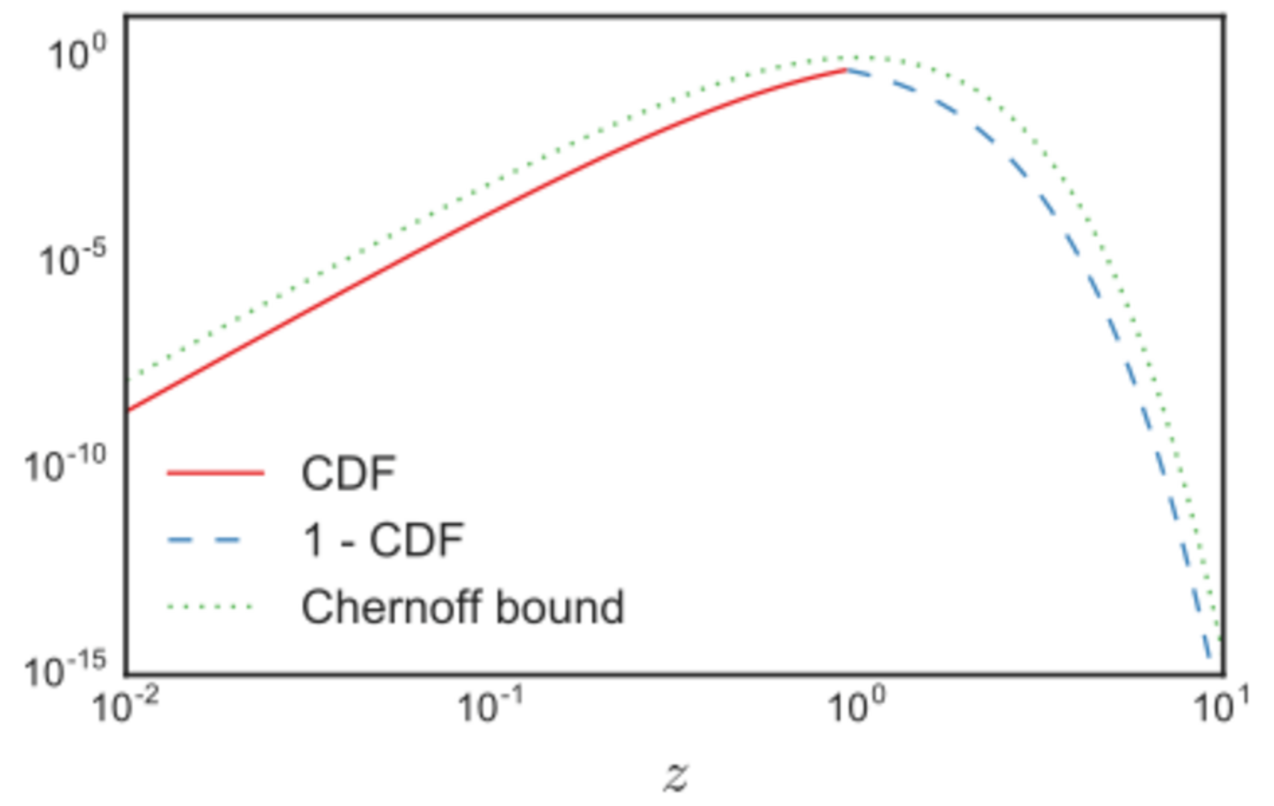

Letting [math]\displaystyle{ z \equiv x/k }[/math], Chernoff bounds on the lower and upper tails of the CDF may be obtained.[4] For the cases when [math]\displaystyle{ 0 \lt z \lt 1 }[/math] (which include all of the cases when this CDF is less than half):

- [math]\displaystyle{ F(z k;\,k) \leq (z e^{1-z})^{k/2}. }[/math]

The tail bound for the cases when [math]\displaystyle{ z \gt 1 }[/math], similarly, is

- [math]\displaystyle{ 1-F(z k;\,k) \leq (z e^{1-z})^{k/2}. }[/math]

For another approximation for the CDF modeled after the cube of a Gaussian, see under Noncentral chi-square distribution.

2. Properties

2.1. Sum of Squares of Independent Identically Distributed Normal Random Variables Minus Their Mean

If Z1, ..., Zk are independent identically distributed (i.i.d.), standard normal random variables, then

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{i=1}^k(Z_i - \overline{Z})^2 \sim \chi^2_{k-1} }[/math]

where

- [math]\displaystyle{ \overline Z = \frac{1}{k} \sum_{i=1}^k Z_i. }[/math]

2.2. Additivity

It follows from the definition of the chi-square distribution that the sum of independent chi-square variables is also chi-square distributed. Specifically, if [math]\displaystyle{ X_i,i=\overline{1,n} }[/math] are independent chi-square variables with [math]\displaystyle{ k_i }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ i=\overline{1,n} }[/math] degrees of freedom, respectively, then [math]\displaystyle{ Y = X_1 + ... + X_n }[/math] is chi-square distributed with [math]\displaystyle{ k_1 + ... + k_n }[/math] degrees of freedom.

2.3. Sample Mean

The sample mean of [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] i.i.d. chi-square variables of degree [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] is distributed according to a gamma distribution with shape [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha }[/math] and scale [math]\displaystyle{ \theta }[/math] parameters:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \overline X = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n X_i \sim \operatorname{Gamma}\left(\alpha=n\, k /2, \theta= 2/n \right) \qquad \text{where } X_i \sim \chi^2(k) }[/math]

Asymptotically, given that for a scale parameter [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha }[/math] going to infinity, a Gamma distribution converges towards a normal distribution with expectation [math]\displaystyle{ \mu = \alpha\cdot \theta }[/math] and variance [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma^2 = \alpha\, \theta^2 }[/math], the sample mean converges towards:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \overline X \xrightarrow{n \to \infty} N(\mu = k, \sigma^2 = 2\, k /n ) }[/math]

Note that we would have obtained the same result invoking instead the central limit theorem, noting that for each chi-square variable of degree [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] the expectation is [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] , and its variance [math]\displaystyle{ 2\,k }[/math] (and hence the variance of the sample mean [math]\displaystyle{ \overline{X} }[/math] being [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma^2 = \frac{2k}{n} }[/math]).

2.4. Entropy

The differential entropy is given by

- [math]\displaystyle{ h = \int_{0}^\infty f(x;\,k)\ln f(x;\,k) \, dx = \frac k 2 + \ln \left[2\,\Gamma \left(\frac k 2 \right)\right] + \left(1-\frac k 2 \right)\, \psi\!\left[\frac k 2 \right], }[/math]

where ψ(x) is the Digamma function.

The chi-square distribution is the maximum entropy probability distribution for a random variate [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] for which [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{E}(X)=k }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{E}(\ln(X))=\psi(k/2)+\ln(2) }[/math] are fixed. Since the chi-square is in the family of gamma distributions, this can be derived by substituting appropriate values in the Expectation of the log moment of gamma. For derivation from more basic principles, see the derivation in moment-generating function of the sufficient statistic.

2.5. Noncentral Moments

The moments about zero of a chi-square distribution with [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] degrees of freedom are given by[5][6]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{E}(X^m) = k (k+2) (k+4) \cdots (k+2m-2) = 2^m \frac{\Gamma\left(m+\frac{k}{2}\right)}{\Gamma\left(\frac{k}{2}\right)}. }[/math]

2.6. Cumulants

The cumulants are readily obtained by a (formal) power series expansion of the logarithm of the characteristic function:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \kappa_n = 2^{n-1}(n-1)!\,k }[/math]

2.7. Concentration

The chi-squared distribution exhibits strong concentration around its mean. The standard Laurent-Massart [7] bounds are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{P}(X - k \ge 2 \sqrt{k x} + 2x) \le \exp(-x) }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{P}(k - X \ge 2 \sqrt{k x}) \le \exp(-x) }[/math]

2.8. Asymptotic Properties

By the central limit theorem, because the chi-square distribution is the sum of [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] independent random variables with finite mean and variance, it converges to a normal distribution for large [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math]. For many practical purposes, for [math]\displaystyle{ k\gt 50 }[/math] the distribution is sufficiently close to a normal distribution for the difference to be ignored.[8] Specifically, if [math]\displaystyle{ X \sim \chi^2(k) }[/math], then as [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] tends to infinity, the distribution of [math]\displaystyle{ (X-k)/\sqrt{2k} }[/math] tends to a standard normal distribution. However, convergence is slow as the skewness is [math]\displaystyle{ \sqrt{8/k} }[/math] and the excess kurtosis is [math]\displaystyle{ 12/k }[/math].

The sampling distribution of [math]\displaystyle{ \ln(\chi^2) }[/math] converges to normality much faster than the sampling distribution of [math]\displaystyle{ \chi^2 }[/math],[9] as the logarithm removes much of the asymmetry.[10] Other functions of the chi-square distribution converge more rapidly to a normal distribution. Some examples are:

- If [math]\displaystyle{ X \sim \chi^2(k) }[/math] then [math]\displaystyle{ \sqrt{2X} }[/math] is approximately normally distributed with mean [math]\displaystyle{ \sqrt{2k-1} }[/math] and unit variance (1922, by R. A. Fisher, see (18.23), p. 426 of Johnson.[11]

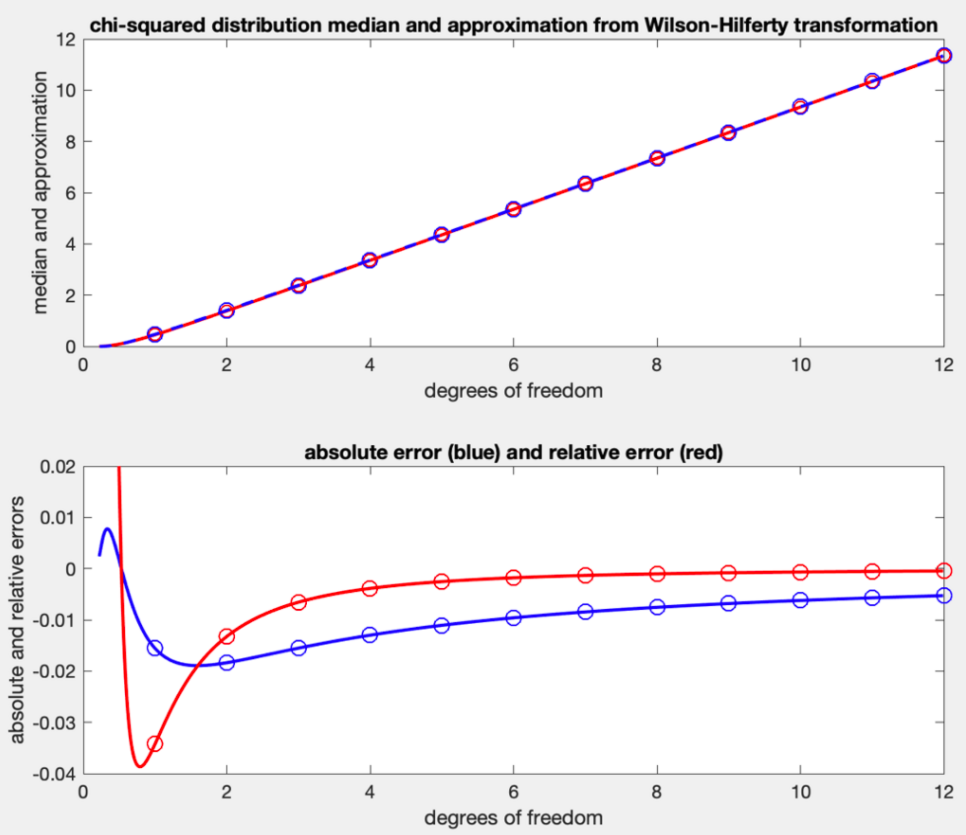

- If [math]\displaystyle{ X \sim \chi^2(k) }[/math] then [math]\displaystyle{ \sqrt[3]{X/k} }[/math] is approximately normally distributed with mean [math]\displaystyle{ 1-\frac{2}{9k} }[/math] and variance [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{2}{9k} . }[/math][12] This is known as the Wilson–Hilferty transformation, see (18.24), p. 426 of Johnson.[11]

- This normalizing transformation leads directly to the commonly used median approximation [math]\displaystyle{ k\bigg(1-\frac{2}{9k}\bigg)^3\; }[/math] by back-transforming from the mean, which is also the median, of the normal distribution.

3. Related Distributions

- As [math]\displaystyle{ k\to\infty }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ (\chi^2_k-k)/\sqrt{2k} ~ \xrightarrow{d}\ N(0,1) \, }[/math] (normal distribution)

- [math]\displaystyle{ \chi_k^2 \sim {\chi'}^2_k(0) }[/math] (noncentral chi-square distribution with non-centrality parameter [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda = 0 }[/math])

- If [math]\displaystyle{ Y \sim \mathrm{F}(\nu_1, \nu_2) }[/math] then [math]\displaystyle{ X = \lim_{\nu_2 \to \infty} \nu_1 Y }[/math] has the chi-square distribution [math]\displaystyle{ \chi^2_{\nu_{1}} }[/math]

-

- As a special case, if [math]\displaystyle{ Y \sim \mathrm{F}(1, \nu_2)\, }[/math] then [math]\displaystyle{ X = \lim_{\nu_2 \to \infty} Y\, }[/math] has the chi-square distribution [math]\displaystyle{ \chi^2_{1} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \|\boldsymbol{N}_{i=1,\ldots,k} (0,1) \|^2 \sim \chi^2_k }[/math] (The squared norm of k standard normally distributed variables is a chi-square distribution with k degrees of freedom)

- If [math]\displaystyle{ X \sim \chi^2(\nu)\, }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ c\gt 0 \, }[/math], then [math]\displaystyle{ cX \sim \Gamma(k=\nu/2, \theta=2c)\, }[/math]. (gamma distribution)

- If [math]\displaystyle{ X \sim \chi^2_k }[/math] then [math]\displaystyle{ \sqrt{X} \sim \chi_k }[/math] (chi distribution)

- If [math]\displaystyle{ X \sim \chi^2(2) }[/math], then [math]\displaystyle{ X \sim \operatorname{Exp}(1/2) }[/math] is an exponential distribution. (See gamma distribution for more.)

- If [math]\displaystyle{ X \sim \chi^2(2k) }[/math], then [math]\displaystyle{ X \sim \operatorname{Erlang}(k, 1/2) }[/math] is an Erlang distribution.

- If [math]\displaystyle{ X \sim \operatorname{Erlang}(k,\lambda) }[/math], then [math]\displaystyle{ 2\lambda X\sim \chi^2_{2k} }[/math]

- If [math]\displaystyle{ X \sim \operatorname{Rayleigh}(1)\, }[/math] (Rayleigh distribution) then [math]\displaystyle{ X^2 \sim \chi^2(2)\, }[/math]

- If [math]\displaystyle{ X \sim \operatorname{Maxwell}(1)\, }[/math] (Maxwell distribution) then [math]\displaystyle{ X^2 \sim \chi^2(3)\, }[/math]

- If [math]\displaystyle{ X \sim \chi^2(\nu) }[/math] then [math]\displaystyle{ \tfrac{1}{X} \sim \operatorname{Inv-}\chi^2(\nu)\, }[/math] (Inverse-chi-square distribution)

- The chi-square distribution is a special case of type III Pearson distribution

- If [math]\displaystyle{ X \sim \chi^2(\nu_1)\, }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ Y \sim \chi^2(\nu_2)\, }[/math] are independent then [math]\displaystyle{ \tfrac{X}{X+Y} \sim \operatorname{Beta}(\tfrac{\nu_1}{2}, \tfrac{\nu_2}{2})\, }[/math] (beta distribution)

- If [math]\displaystyle{ X \sim \operatorname{U}(0,1)\, }[/math] (uniform distribution) then [math]\displaystyle{ -2\log(X) \sim \chi^2(2)\, }[/math]

- If [math]\displaystyle{ X_i \sim \operatorname{Laplace}(\mu,\beta)\, }[/math] then [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{i=1}^n \frac{2 |X_i-\mu|}{\beta} \sim \chi^2(2n)\, }[/math]

- If [math]\displaystyle{ X_i }[/math] follows the generalized normal distribution (version 1) with parameters [math]\displaystyle{ \mu,\alpha,\beta }[/math] then [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{i=1}^n \frac{2 |X_i-\mu|^\beta}{\alpha} \sim \chi^2\left(\frac{2n}{\beta}\right)\, }[/math] [13]

- chi-square distribution is a transformation of Pareto distribution

- Student's t-distribution is a transformation of chi-square distribution

- Student's t-distribution can be obtained from chi-square distribution and normal distribution

- Noncentral beta distribution can be obtained as a transformation of chi-square distribution and Noncentral chi-square distribution

- Noncentral t-distribution can be obtained from normal distribution and chi-square distribution

A chi-square variable with [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] degrees of freedom is defined as the sum of the squares of [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] independent standard normal random variables.

If [math]\displaystyle{ Y }[/math] is a [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math]-dimensional Gaussian random vector with mean vector [math]\displaystyle{ \mu }[/math] and rank [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] covariance matrix [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math], then [math]\displaystyle{ X = (Y-\mu )^{T}C^{-1}(Y-\mu) }[/math] is chi-square distributed with [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] degrees of freedom.

The sum of squares of statistically independent unit-variance Gaussian variables which do not have mean zero yields a generalization of the chi-square distribution called the noncentral chi-square distribution.

If [math]\displaystyle{ Y }[/math] is a vector of [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] i.i.d. standard normal random variables and [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] is a [math]\displaystyle{ k\times k }[/math] symmetric, idempotent matrix with rank [math]\displaystyle{ k-n }[/math], then the quadratic form [math]\displaystyle{ Y^TAY }[/math] is chi-square distributed with [math]\displaystyle{ k-n }[/math] degrees of freedom.

If [math]\displaystyle{ \Sigma }[/math] is a [math]\displaystyle{ p\times p }[/math] positive-semidefinite covariance matrix with strictly positive diagonal entries, then for [math]\displaystyle{ X\sim N(0,\Sigma) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ w }[/math] a random [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math]-vector independent of [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ w_1+\cdots+w_p=1 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ w_i\geq 0, i=1,\cdots,p, }[/math] it holds that

[math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{\left(\frac{w_1}{X_1},\cdots,\frac{w_p}{X_p}\right)\Sigma\left(\frac{w_1}{X_1},\cdots,\frac{w_p}{X_p}\right)^{\top}}\sim\chi_1^2. }[/math][10]

The chi-square distribution is also naturally related to other distributions arising from the Gaussian. In particular,

- [math]\displaystyle{ Y }[/math] is F-distributed, [math]\displaystyle{ Y \sim F(k_1, k_2) }[/math] if [math]\displaystyle{ Y = \frac{ {X_1}/{k_1} }{ {X_2}/{k_2} } }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ X_1 \sim \chi^2(k_1) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ X_2 \sim \chi^2(k_2) }[/math] are statistically independent.

- If [math]\displaystyle{ X_1 \sim \chi^2(k_1) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ X_2 \sim \chi^2(k_2) }[/math] are statistically independent, then [math]\displaystyle{ X_1 + X_2\sim \chi^2(k_1+k_2) }[/math]. If [math]\displaystyle{ X_1 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ X_2 }[/math] are not independent, then [math]\displaystyle{ X_1+X_2 }[/math] is not chi-square distributed.

3.1. Generalizations

The chi-square distribution is obtained as the sum of the squares of k independent, zero-mean, unit-variance Gaussian random variables. Generalizations of this distribution can be obtained by summing the squares of other types of Gaussian random variables. Several such distributions are described below.

3.2. Linear Combination

If [math]\displaystyle{ X_1,\ldots,X_n }[/math] are chi square random variables and [math]\displaystyle{ a_1,\ldots,a_n\in\mathbb{R}_{\gt 0} }[/math], then a closed expression for the distribution of [math]\displaystyle{ X=\sum_{i=1}^n a_i X_i }[/math] is not known. It may be, however, approximated efficiently using the property of characteristic functions of chi-square random variables.[14]

3.3. Chi-Square Distributions

Noncentral chi-square distribution

The noncentral chi-square distribution is obtained from the sum of the squares of independent Gaussian random variables having unit variance and nonzero means.

Generalized chi-square distribution

The generalized chi-square distribution is obtained from the quadratic form z′Az where z is a zero-mean Gaussian vector having an arbitrary covariance matrix, and A is an arbitrary matrix.

The chi-square distribution [math]\displaystyle{ X \sim \chi_k^2 }[/math] is a special case of the gamma distribution, in that [math]\displaystyle{ X \sim \Gamma \left(\frac{k}2,\frac{1}2\right) }[/math] using the rate parameterization of the gamma distribution (or [math]\displaystyle{ X \sim \Gamma \left(\frac{k}2,2 \right) }[/math] using the scale parameterization of the gamma distribution) where k is an integer.

Because the exponential distribution is also a special case of the gamma distribution, we also have that if [math]\displaystyle{ X \sim \chi_2^2 }[/math], then [math]\displaystyle{ X\sim \operatorname{Exp}\left(\frac 1 2\right) }[/math] is an exponential distribution.

The Erlang distribution is also a special case of the gamma distribution and thus we also have that if [math]\displaystyle{ X \sim\chi_k^2 }[/math] with even [math]\displaystyle{ \text{k} }[/math], then [math]\displaystyle{ \text{X} }[/math] is Erlang distributed with shape parameter [math]\displaystyle{ \text{k}/2 }[/math] and scale parameter [math]\displaystyle{ 1/2 }[/math].

4. Occurrence and Applications

The chi-square distribution has numerous applications in inferential statistics, for instance in chi-square tests and in estimating variances. It enters the problem of estimating the mean of a normally distributed population and the problem of estimating the slope of a regression line via its role in Student's t-distribution. It enters all analysis of variance problems via its role in the F-distribution, which is the distribution of the ratio of two independent chi-squared random variables, each divided by their respective degrees of freedom.

Following are some of the most common situations in which the chi-square distribution arises from a Gaussian-distributed sample.

- if [math]\displaystyle{ X_1, ..., X_n }[/math] are i.i.d. [math]\displaystyle{ N(\mu, \sigma^2) }[/math] random variables, then [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{i=1}^n(X_i - \overline{X})^2 \sim \sigma^2 \chi^2_{n-1} }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ \overline X = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n X_i }[/math].

- The box below shows some statistics based on [math]\displaystyle{ X_i \sim N(\mu_i, \sigma^2_i), i= 1, \ldots, k }[/math] independent random variables that have probability distributions related to the chi-square distribution:

| Name | Statistic |

|---|---|

| chi-square distribution | [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{i=1}^k \left(\frac{X_i-\mu_i}{\sigma_i}\right)^2 }[/math] |

| noncentral chi-square distribution | [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{i=1}^k \left(\frac{X_i}{\sigma_i}\right)^2 }[/math] |

| chi distribution | [math]\displaystyle{ \sqrt{\sum_{i=1}^k \left(\frac{X_i-\mu_i}{\sigma_i}\right)^2} }[/math] |

| noncentral chi distribution | [math]\displaystyle{ \sqrt{\sum_{i=1}^k \left(\frac{X_i}{\sigma_i}\right)^2} }[/math] |

The chi-square distribution is also often encountered in magnetic resonance imaging.[15]

5. Computational Methods

5.1. Table of χ2 Values vs p-Values

The p-value is the probability of observing a test statistic at least as extreme in a chi-square distribution. Accordingly, since the cumulative distribution function (CDF) for the appropriate degrees of freedom (df) gives the probability of having obtained a value less extreme than this point, subtracting the CDF value from 1 gives the p-value. A low p-value, below the chosen significance level, indicates statistical significance, i.e., sufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis. A significance level of 0.05 is often used as the cutoff between significant and non-significant results.

The table below gives a number of p-values matching to [math]\displaystyle{ \chi^2 }[/math] for the first 10 degrees of freedom.

| Degrees of freedom (df) | [math]\displaystyle{ \chi^2 }[/math] value[16] | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.004 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.46 | 1.07 | 1.64 | 2.71 | 3.84 | 6.63 | 10.83 |

| 2 | 0.10 | 0.21 | 0.45 | 0.71 | 1.39 | 2.41 | 3.22 | 4.61 | 5.99 | 9.21 | 13.82 |

| 3 | 0.35 | 0.58 | 1.01 | 1.42 | 2.37 | 3.66 | 4.64 | 6.25 | 7.81 | 11.34 | 16.27 |

| 4 | 0.71 | 1.06 | 1.65 | 2.20 | 3.36 | 4.88 | 5.99 | 7.78 | 9.49 | 13.28 | 18.47 |

| 5 | 1.14 | 1.61 | 2.34 | 3.00 | 4.35 | 6.06 | 7.29 | 9.24 | 11.07 | 15.09 | 20.52 |

| 6 | 1.63 | 2.20 | 3.07 | 3.83 | 5.35 | 7.23 | 8.56 | 10.64 | 12.59 | 16.81 | 22.46 |

| 7 | 2.17 | 2.83 | 3.82 | 4.67 | 6.35 | 8.38 | 9.80 | 12.02 | 14.07 | 18.48 | 24.32 |

| 8 | 2.73 | 3.49 | 4.59 | 5.53 | 7.34 | 9.52 | 11.03 | 13.36 | 15.51 | 20.09 | 26.12 |

| 9 | 3.32 | 4.17 | 5.38 | 6.39 | 8.34 | 10.66 | 12.24 | 14.68 | 16.92 | 21.67 | 27.88 |

| 10 | 3.94 | 4.87 | 6.18 | 7.27 | 9.34 | 11.78 | 13.44 | 15.99 | 18.31 | 23.21 | 29.59 |

| P value (Probability) | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.80 | 0.70 | 0.50 | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.001 |

These values can be calculated evaluating the quantile function (also known as “inverse CDF” or “ICDF”) of the chi-square distribution;[17] e. g., the χ2 ICDF for p = 0.05 and df = 7 yields 2.1673 ≈ 2.17 as in the table above, noticing that 1 - p is the p-value from the table.

6. History

This distribution was first described by the German statistician Friedrich Robert Helmert in papers of 1875–6,[18][19] where he computed the sampling distribution of the sample variance of a normal population. Thus in German this was traditionally known as the Helmert'sche ("Helmertian") or "Helmert distribution".

The distribution was independently rediscovered by the English mathematician Karl Pearson in the context of goodness of fit, for which he developed his Pearson's chi-square test, published in 1900, with computed table of values published in (Elderton 1902), collected in (Pearson 1914). The name "chi-square" ultimately derives from Pearson's shorthand for the exponent in a multivariate normal distribution with the Greek letter Chi, writing −½χ2 for what would appear in modern notation as −½xTΣ−1x (Σ being the covariance matrix).[20] The idea of a family of "chi-square distributions", however, is not due to Pearson but arose as a further development due to Fisher in the 1920s.[18]

References

- Westfall, Peter H. (2013). Understanding Advanced Statistical Methods. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4665-1210-8.

- Ramsey, PH (1988). "Evaluating the Normal Approximation to the Binomial Test". Journal of Educational Statistics 13 (2): 173–82. doi:10.2307/1164752. https://dx.doi.org/10.2307%2F1164752

- Lancaster, H.O. (1969), The Chi-squared Distribution, Wiley

- Dasgupta, Sanjoy D. A.; Gupta, Anupam K. (January 2003). "An Elementary Proof of a Theorem of Johnson and Lindenstrauss". Random Structures and Algorithms 22 (1): 60–65. doi:10.1002/rsa.10073. http://cseweb.ucsd.edu/~dasgupta/papers/jl.pdf. Retrieved 2012-05-01.

- Chi-squared distribution, from MathWorld, retrieved Feb. 11, 2009 http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Chi-SquaredDistribution.html

- M. K. Simon, Probability Distributions Involving Gaussian Random Variables, New York: Springer, 2002, eq. (2.35), ISBN:978-0-387-34657-1

- https://projecteuclid.org/journals/annals-of-statistics/volume-28/issue-5/Adaptive-estimation-of-a-quadratic-functional-by-model--selection/10.1214/aos/1015957395.full, Lemma 1, retrieved May 1, 2021

- Box, Hunter and Hunter (1978). Statistics for experimenters. Wiley. p. 118. ISBN 978-0471093152. https://archive.org/details/statisticsforexp00geor/page/118.

- Bartlett, M. S.; Kendall, D. G. (1946). "The Statistical Analysis of Variance-Heterogeneity and the Logarithmic Transformation". Supplement to the Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 8 (1): 128–138. doi:10.2307/2983618. https://dx.doi.org/10.2307%2F2983618

- Pillai, Natesh S. (2016). "An unexpected encounter with Cauchy and Lévy". Annals of Statistics 44 (5): 2089–2097. doi:10.1214/15-aos1407. https://dx.doi.org/10.1214%2F15-aos1407

- Johnson, N. L.; Kotz, S.; Balakrishnan, N. (1994). "Chi-Square Distributions including Chi and Rayleigh". Continuous Univariate Distributions. 1 (Second ed.). John Wiley and Sons. pp. 415–493. ISBN 978-0-471-58495-7.

- Wilson, E. B.; Hilferty, M. M. (1931). "The distribution of chi-squared". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 17 (12): 684–688. doi:10.1073/pnas.17.12.684. PMID 16577411. Bibcode: 1931PNAS...17..684W. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1076144

- Bäckström, T.; Fischer, J. (January 2018). "Fast Randomization for Distributed Low-Bitrate Coding of Speech and Audio". IEEE/ACM Transactions on Audio, Speech, and Language Processing 26 (1): 19–30. doi:10.1109/TASLP.2017.2757601. https://aaltodoc.aalto.fi/handle/123456789/33466.

- Bausch, J. (2013). "On the Efficient Calculation of a Linear Combination of Chi-Square Random Variables with an Application in Counting String Vacua". J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 46 (50): 505202. doi:10.1088/1751-8113/46/50/505202. Bibcode: 2013JPhA...46X5202B. https://dx.doi.org/10.1088%2F1751-8113%2F46%2F50%2F505202

- den Dekker A. J., Sijbers J., (2014) "Data distributions in magnetic resonance images: a review", Physica Medica, [1]

- Chi-Squared Test Table B.2. Dr. Jacqueline S. McLaughlin at The Pennsylvania State University. In turn citing: R. A. Fisher and F. Yates, Statistical Tables for Biological Agricultural and Medical Research, 6th ed., Table IV. Two values have been corrected, 7.82 with 7.81 and 4.60 with 4.61 http://www2.lv.psu.edu/jxm57/irp/chisquar.html

- R Tutorial: Chi-squared Distribution http://www.r-tutor.com/elementary-statistics/probability-distributions/chi-squared-distribution

- Hald 1998, pp. 633–692, 27. Sampling Distributions under Normality.

- F. R. Helmert, "Ueber die Wahrscheinlichkeit der Potenzsummen der Beobachtungsfehler und über einige damit im Zusammenhange stehende Fragen", Zeitschrift für Mathematik und Physik 21, 1876, pp. 102–219 http://gdz.sub.uni-goettingen.de/dms/load/img/?PPN=PPN599415665_0021&DMDID=DMDLOG_0018

- R. L. Plackett, Karl Pearson and the Chi-Squared Test, International Statistical Review, 1983, 61f. See also Jeff Miller, Earliest Known Uses of Some of the Words of Mathematics. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1402731?seq=3