Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ángel Acevedo-Duque | + 3319 word(s) | 3319 | 2022-03-04 03:29:32 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | -504 word(s) | 2815 | 2022-03-22 07:21:58 | | | | |

| 3 | Conner Chen | -15 word(s) | 2800 | 2022-03-22 07:29:10 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Acevedo-Duque, �. PERVAINCONSA Scale to Measure Consumer Behavior. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20819 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Acevedo-Duque �. PERVAINCONSA Scale to Measure Consumer Behavior. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20819. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Acevedo-Duque, Ángel. "PERVAINCONSA Scale to Measure Consumer Behavior" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20819 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Acevedo-Duque, �. (2022, March 21). PERVAINCONSA Scale to Measure Consumer Behavior. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20819

Acevedo-Duque, Ángel. "PERVAINCONSA Scale to Measure Consumer Behavior." Encyclopedia. Web. 21 March, 2022.

Copy Citation

The PERVAINCONSA Scale (acrostic formed with the initial letters of the Spanish words “Percepción de Valor”, “Intención de Compra”, “Confianza” and “Satisfacción”) was constructed. It aims to validate an instrument designed to measure the variables value perception, purchase intention, trust, and satisfaction of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) dedicated to selling clothing.

value perception

consumer behavior

PERVAINCONSA scale

1. Introduction

Consumer behavior has faced several crises, such as the Great Depression of the 1930s, the financial crisis of the early 2000s, and, currently, COVID-19, which have led to changes in consumer consumption patterns [1][2]. One of the most obvious changes was the use of digital technology to perform different activities of daily life, with consumer resistance to the use of technology being as important an aspect of such behavior as acceptance and adoption [3].

In this sense, e-commerce has long generated great social and economic benefits in countries, leading them to add productive processes towards sustainable development [4], while in developing countries, the lack of technology and knowledge has limited its adoption [5]; however, the impact of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) accelerated the growth of e-commerce [6] and sales have adapted to the 4.0 era, which has become a need for adaptation and resilience for large, medium, and small companies worldwide to remain sustainable with their businesses [7].

According to Ref. [3], consumer resistance to the use of technology is one of the main reasons for the failure of market innovations; however, digital technology is increasingly essential for children, young people, adults, and the elderly, as it facilitates communication with others through mobile devices or computers that connect to the Internet [8][9].

The new reality forces countries and their companies not only to adapt to e-commerce to sell, but also to maintain a good relationship with their consumers [10]. Offering a good online shopping experience to consumers allows them to generate repurchase and recommend the store [6][11]. Consumers’ purchase decision is mediated by different factors, including perceived value, purchase intention, trust, and satisfaction [11].

Therefore, the importance of this research is to measure these variables for companies to improve their business management and increase their competitiveness and sustainability in their production processes [12]. Identifying and analyzing aspects such as perceived value, purchase intention, trust, and satisfaction of the different stakeholders involved in a commercial process helps organizations to validate representative aspects in customers and to know their perception of the products offered and the quality of the service that is part of the value offer; it also helps to know the intention of consumers, buyers or users of a brand when making a decision and carrying out the commercial transaction [13].

Perceived value is one of the factors that make consumers evaluate products or services after weighing the perceived benefits and sacrifices [1][14]. When comparing price with what they are going to get, consumers choose the option that offers the highest perceived value [15][16]. Consumers evaluate an online store from a hedonic or utilitarian aspect [5]; concerning the hedonic aspect, this encompasses the emotional and affective part of the buying process [15], whereas the utilitarian aspect is based on the cognitive and rational evaluation of the consumer [17].

As for online purchase intention, this refers to the consumer’s willingness to make a purchase from an online store [5]. According to economic theory, consumers choose an item to purchase rationally and according to their limited resources [18]; however, from the psychological perspective, Ref. [19] considers purchase intention as the will that the consumer manifests in terms of effort and action to perform a certain behavior. According to Ref. [20], this is associated with a set of variables such as previous experience, preferences, and external environment to gather information, evaluate alternatives and finally make a purchase decision [17].

In the shopping experience, trust is a fundamental factor, a key strategy for marketing and long-term relationship success [5]. Ref. [21] defines trust as the perception that a party has towards its interlocutor in terms of reliability and integrity. In relation to e-trust, e-trust is defined as an attitude of confident expectation in an online risk situation that one’s vulnerabilities will not be exploited. In this sense, trust emerges as a potentially central element leading to the acceptance of information technologies and is especially necessary for online marketers [22][23].

Today’s business environment, specifically in Latin America, is highly competitive, and repeat purchases are a necessary phenomenon to ensure the survival of organizations of this type, leading to customer retention [24]. In this sense, satisfaction is an important indicator of increasing customer loyalty [25]. Satisfaction of customer needs is the key to exchanges between companies and markets, and since the origins of marketing, satisfaction has been considered the determinant of success in markets [24]. According to customer value theory, satisfaction is the result of the perception of the value received by the customer over the expected value, so that loyalty is the result of customers’ belief that the amount of value received is superior to what they can obtain from other sellers [26].

This highlights the research question of how the PERVAINCONSA Scale could measure the consumer behavior of online stores of MSMEs engaged in the sale of clothing, and the importance of the research objective in understanding the variables associated with the online purchase decision. Having an instrument to articulately measure value perception, purchase intention, trust, and consumer satisfaction is necessary for the consolidation of an organizational culture that improves marketing and management conditions in the competitive context of the markets. There are several instruments that evaluate the factors that determine the purchase decision of consumers in an online store, for example, the PERVAL scale of Ref. [27], SERVQUAL of Ref. [28], SERVPERF of Ref. [29], and WebQuall of Ref. [30], among others, serve as a basis for the authors to adapt them according to their research.

2. Consumer Behavior in Developing Countries Seeking Sustainability

The use of technology in the current era has become an integral part of the consumer’s daily life, where it is not only used for social communication, information seeking, education, commerce, and entertainment but is also immediately available to consumers [14]. Consumer behaviors are understood as all those internal and external activities of an individual or group of individuals aimed at satisfying their needs.

In the case of Latin American developing countries, in the last seven years, collaborative models have been emerging through startups, and have been taking a market position as a substitute for traditional capitalist business models [31][32]; however, the pace of growth and number of existing collaborative models is not the same in other countries of the world.

For the authors of Ref. [33], they refer to the fact that the study of consumer behavior is of interest to the whole society since we are all consumers. From the perspective of the company in developing Latin American countries, marketing managers must know everything that affects their market in order to design successful commercial policies [34][35]. Knowing consumers’ tastes and preferences will help to correctly segment the market and make it more sustainable.

New consumer behavior refers to the internal and external dynamics of the individual, which takes place when seeking to satisfy their needs with goods and services [36][37]. Applied to the realization that is found in these countries, it is the decision process and the physical activity to search, evaluate and acquire goods and services to satisfy the needs has been a very dynamic issue that projects sustainable actions in the productive processes of business.

This behavior starts with the existence of an area which is lacking, the recognition of a need, the search for satisfaction alternatives, the purchase decision, and the subsequent evaluation (before, during, and after) [38]. The above shows that consumer behavior is the exchange of goods between individuals, groups, and companies, to satisfy their needs, involving aspects such as individual consumers, children, men, adults, housewives, groups, families, companies and groups, internal and external phenomena, the brand, perception, advertising, search, and purchase [39][40][41].

In recent years, several studies have proposed new ways of classifying consumers, taking into consideration their concern for environmental conservation, i.e., the quality and price of the product is no longer enough to satisfy the needs of customers, but also the level of trust and commitment to the organizations and products that these consumers perceive at the time of making the purchase. Trust is the level at which the customer considers that a product solves a problem, and commitment shows the level of sacrifice that the customer is willing to make to acquire the product or service. In this sense, four groups of customers can be identified: (1) those who make win-win purchases, i.e., the customer, the company and the environment; (2) those who buy to feel good, when the customer makes a small sacrifice at the time of purchase; (3) those who question “why not buy” when the consumer’s sacrifice and confidence is low; (4) those who question why they should buy the product, which occurs when the consumer feels insecure about the quality [42][43][44].

Consumers who are concerned about caring for the environment are reluctant to consume products that require a high use of energy and resources to produce them, that generate intensive waste due to packaging or short shelf life, that use materials that negatively affect the inhabitants of the area, and also endanger their health or the health of others [45]. In recent years, a group of consumers committed to health and sustainability “LOHAS” has emerged, who are differentiating themselves by their healthy lifestyle and also try to satisfy their needs by acquiring products and/or services that do not harm the environment and society [45][46]; however, there is another sector of consumers who are not willing to spend time to read the description of the composition of the products they purchase, so a company that wants to contribute to sustainable development and launch eco-friendly products, should carry out efforts to educate consumers so that they are willing to buy environmentally friendly products [47].

3. Perception of Value in the Purchase Intention of the Online Consumer

The authors [48][49] explain how in recent decades the advance of the Internet and social networks has modified consumer habits and how consumers rigorously manage their value when acquiring goods or services. More and more information is being exchanged through these networks [50]. In any campaign, it is necessary to know the target audience to which the strategy actions are addressed in order to generate actions that encourage purchases.

The author of Ref. [49], mentions in his work that human beings are alternatively irrational; that is, we combine periods of rationality with unexpected irrational irruptions. We often act without thinking, and do things wrongly or mistakenly [51]. Today’s online purchasing decisions are highly influenced by the emotional and personal, and can be mixed with lapses of irrationality. Thus, sometimes, we opt for a product for no reason at all, since we do not make all decisions rationally, especially when making purchasing decisions [52][53][54][55][56][57][58]. Purchasing decisions are wrapped in subjectivity, which makes it difficult to build models to predict consumer behavior, since when irrationality interrupts, there is no model that will work.

According to authors such as Refs. [53][54][59], the perception of value in the purchase intention in the online consumer is that the subject gives the object a meaning, and thus when making a purchase, it generates satisfaction or momentary pleasure; it is also seen by others as a phenomenon that shows a feeling of weak self-esteem: it is more important the action derived from the purchase than the actual possession of the goods [55].

Finally, most of the things that consumers buy, they do not need [56]. For this reason, the branches of commercial strategies aim to create needs in the subject so that they feel the need to buy by any means, the current one being online shopping [57], i.e., they must know the consumer behavior to carry out a good business, which sustains the companies to satisfy the needs of consumers. These cannot be satisfied correctly if we do not understand the people who would use the products and services [58].

4. PERVAINCONSA Scale to Measure Consumer Behavior

The PERVAINCONSA Scale (acrostic formed with the initial letters of the Spanish words (“Perception of Value”, “Purchase Intention”, “Confidence” and “Satisfaction”), was created due to the need to measure the three variables together, such as satisfaction, loyalty, value perception, and purchase intention, focused on the online stores of MSMEs dedicated to the sale of clothing in developing countries. Currently, there is no instrument in the scientific literature that allows the joint evaluation of these three variables to understand the behavior of current and potential customers in virtual environments of these types of companies, which make an important contribution to the economies of developing countries. It is, therefore, necessary to design instruments that facilitate decision-making and efficient business and marketing management, for the sustainability of companies in these times of global economic crisis produced by COVID-19, which has generated new lifestyles and behavior among consumers.

In the elaboration of the scale, various works found in the scientific literature were considered as a basis, among which are the PERVAL scale to measure perceived value, proposed by [27], which is composed of 4 dimensions such as quality, price, social value, and emotional value; the technology acceptance model (TAM) presented by [60], a model that is related on the basis of a consecutive influential relationship (belief, attitude, intention) [8][10][61] and the model of [17] that contrasts the influence of perceived value and trust with online purchase intention.

The scale measures satisfaction in relation to the quality of the service offered and the positive emotions generated by the product [54][62]. Regarding loyalty, this is related to the quality of the product, the experience of browsing the website, and trust in the brand, because loyalty can be measured in terms of visits and interaction with the website over time [54]; finally, the perception of value is evaluated according to the functionality of the product (utilitarian, emotional and social) [17][24][27][62].

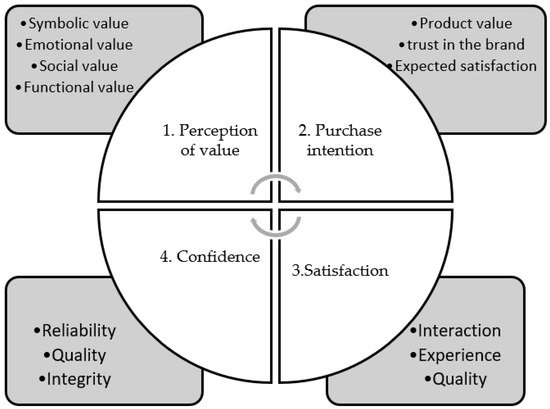

Becker [63][64][65], incorporates into the theory of consumer behavior the influence that becomes, replacing the individual, the decision unit. For this author, the consumer group behaves like a small-scale factory in which it is a question of allocating the time of its different members and the basic capital—housing, electrical appliances, automobiles—and raw materials, such as food and clothing, to obtain the greatest amount of assets: good food, healthy children, leisure or social relations, among others [66] (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. PERVAINCONSA model.

As consumer behaviors, we understand all those internal and external activities of an individual or group of individuals directed towards the satisfaction of their needs. This behavior starts from the existence of a lack, the recognition of a need, the search for satisfaction alternatives, the purchase decision, and the subsequent evaluation (before, during and after) [67].

4.1. Value Perception

Value perception is defined as the judgment made by the consumer regarding the feeling he/she experiences (positive or negative), after buying online and comparing the price paid with the product received [16]. The value perceived by customers is affected by the expectations created by the benefits offered by the use of a product and what it actually provides, according to the values pursued; so that, in the electronic channel, ref. [5] consider that the values that best explain the personal decision to buy or not a certain product are the perceived symbolic value and the functional value. The symbolic value of a product allows reflecting the type of person the consumer is or what he wants to be since this value brings together social, emotional, aesthetic, and reputational aspects experienced by the consumer [68]; while the functional value is based on the consumers’ perception of the utilitarian or economic benefits or sacrifices, he experiences in relation to the quality, price and convenience features he obtains from a product [14][69].

4.2. Purchase Intention

The purchase intention of an online consumer refers to the openness of the consumer to make a purchase in a particular online store [17]. According to the theory of action reasoning [70], the purchase intention precedes the immediate action of carrying it out, which can be long-lasting and associated with the emotions and attitudes of the consumer [71]. Studies show that online purchase intention is affected by product value, brand trust and the expectations that consumers want to satisfy [5][14].

4.3. Satisfaction

4.4. Trust

Trust is defined as the confidence that the consumer has in a store, based on the positive expectations generated after perceiving the intentions and behavior of the seller [69] In online shopping, trust refers to the positive image that people create regarding the quality, integrity, and reliability that a brand provides after interacting with the online store or having made a purchase [17][22] being integrity an attribute of a socially responsible brand highly valued in the new normality [75].

Figure 1 PERVAINCONSA Scale to measure consumer behavior.

References

- González-Díaz, R.R.; Acevedo-Duque, Á.E.; Guanilo-Gómez, S.L.; Cachicatari-Vargas, E. Business counterintelligence as a protection strategy for SMEs. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2021, 8, 340–352.

- Portuguez Castro, M.; Gómez Zermeño, M.G. Being an entrepreneur post-COVID-19—Resilience in times of crisis: A systematic literature review. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2020, 13, 721–746.

- Talwar, S.; Talwar, M.; Kaur, P.; Dhir, A. Consumers’ resistance to digital innovations: A systematic review and framework development. Australas Mark. J. 2020, 28, 286–299.

- Baabdullah, A.M. Consumer adoption of Mobile Social Network Games (M-SNGs) in Saudi Arabia: The role of social influence, hedonic motivation and trust. Technol Soc. 2018, 53, 91–102.

- Peña-García, N.; Gil-Saura, I.; Rodríguez-Orejuela, A. Emoción y razón: El efecto moderador del género en el comportamiento de compra online. Innovar 2018, 28, 117–132.

- Palomino Pita, A.F.; Carolina, M.V.; Oblitas Cruz, J.F. E-commerce and its importance in times of covid-19 in Northern Peru. Rev. Venez. Gerenc. 2020, 25, 253–266.

- Sun, L.; Zhao, Y.; Ling, B. The joint influence of online rating and product price on purchase decision: An EEG study. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2020, 13, 291–301.

- Guner, H.; Acarturk, C. The use and acceptance of ICT by senior citizens: A comparison of technology acceptance model (TAM) for elderly and young adults. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2020, 19, 311–330.

- Bencsik, A.; Machová, R.; Zsigmond, T. Analysing customer behaviour in mobile app usage among the representatives of generation X and generation Y. J. Appl. Econ. Sci. 2018, 13, 1668–1677.

- Fu, S.; Yan, Q.; Feng, G.C. Who will attract you? Similarity effect among users on online purchase intention of movie tickets in the social shopping context. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 40, 88–102.

- Kamal, M.; Aljohani, A.; Alanazi, E. Iot Meets Covid-19: Status, Challenges, and Opportunities. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2007.12268.

- Müller, J.; Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Müller, S.; Kalia, P.; Mehmood, K. Predictive sustainability model based on the theory of planned behavior incorporating ecological conscience and moral obligation. Sustainablity 2021, 13, 4248.

- Poole, S.M.; Campos, N.M. Transfer of marketing knowledge to Catholic primary schools. Int. J. Nonprofit. Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2017, 22, e1579.

- Suo, L.; Lu, R.C.; Lin, G.D.i. Analysis of factors inuencing consumers’ purchase intention based on perceived value in e-commerce clothing pre-sale model. J. Fiber Bioeng. Inform. 2020, 13, 23–36.

- Acquila-Natale, E.; Iglesias-Pradas, S. A matter of value? Predicting channel preference and multichannel behaviors in retail. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 162, 120401.

- Yin, J.; Qiu, X. Ai technology and online purchase intention: Structural equation model based on perceived value. Sustainability 2021, 8, 5671.

- Peña García, N. El valor percibido y la confianza como antecedentes de la intención de compra online: El caso colombiano. Cuad Adm. 2014, 30, 15–24.

- Alonso Rivas, J.; Grande Esteban, I. Comportamiento del Consumidor. Decisiones y Estrategias de Marketing, 8th ed.; ESIC Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2017; pp. 27–29.

- Ajzen, I. The social psychology of decision making. In Social Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles; Higgins, E.T., Kruglanski, A.W., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 297–325.

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer Perceptions of Price, Quality, and Value: A Means-End Model and Synthesis of Evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22.

- Morgan, R.M.; Hunt, S.D. The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20.

- Bhat, S.A.; Darzi, M.A. Online Service Quality Determinants and E-trust in Internet Shopping: A Psychometric Approach. J. Decis. Makers 2020, 45, 207–222.

- Chen, T. Personality Traits Hierarchy of Online Shoppers. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2011, 3, 23–39.

- Sánchez Pérez, M.; GGallarza, M.; Berenguer Contrí, G.; Gil Saura, I. Encuentro de servicio, valor percibido y satisfacción del cliente en la relación entre empresas. Cuad. Estud. Empres. 2005, 15, 47–72.

- Segoro, W.; Limakrisna, N. Model of customer satisfaction and loyality. Utop. Y Prax. Latinoam. 2020, 25, 166–175.

- Foroudi, P.; Cuomo, M.T.; Foroudi, M.M. Continuance interaction intention in retailing: Relations between customer values, satisfaction, loyalty, and identification. Inf. Technol. People 2020, 33, 1303–1326.

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220.

- Parasuraman, A.A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. Refinement and reassessment of the SERVQUAL instrument. J. Retail. 1991, 67, 420–450.

- Cronin, J.J.; Taylor, S.A. Measuring Service Quality: A Reexamination and Extension. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 55.

- Barnes, S.; Vidgen, R. An Integrative Approach to the Assessment of E-Commerce Quality. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2002, 3, 114–127.

- Foxall, G.R. Theoretical and conceptual advances in consumer behavior analysis: Invitation to consumer behavior analysis. J. Organ. Behav. Manag. 2010, 30, 92–109.

- Benites, M.; González-Díaz, R.R.; Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Becerra-Pérez, L.A.; Tristancho Cediel, G. Latin American microentrepreneurs: Trajectories and meanings about informal work. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5449.

- Rivera, J.; Arellano, R.; Molero, V.M. Conducta del Consumidor, Estrategias y Políticas Aplicadas al Marketing; ESIC Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2013; Volume 53, pp. 1689–1699.

- Hernandez, B.; Jimenez, J.; Martín, M.J. Adoption vs. acceptance of e-commerce: Two different decisions. Eur. J. Mark. 2009, 43, 1232–1245.

- Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Gonzalez-Diaz, R.; Cachicatari Vargas, E.; Paz-Marcano, A.; Muller-Pérez, S.; Salazar-Sepúlveda, G.; Caruso, G.; D’Adamo, I. Resilience, leadership and female entrepreneurship within the context of smes: Evidence from latin america. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8129.

- Reed, A.; Forehand, M.R.; Puntoni, S.; Warlop, L. Identity-based consumer behavior. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2012, 29, 310–321.

- Hermann, E. Anthropomorphized artificial intelligence, attachment, and consumer behavior. Mark. Lett. 2021, 0123456789.

- Balova, S.; Firsova, I.; Osipova, I. Market leading marketing concepts in the management of consumer behaviour on the energy market. Adv. Soc. Sci. Educ. Humanit. Res. 2019, 318, 354–360.

- Puplampu, G.L.; Fenny, A.P.; Mensah, G. Consumers and consumer behaviour. Health Serv. Mark. Manag. Afr. Taylor Fr. 2019, 57–70.

- Pushkar, O.; Kurbatova, Y.; Druhova, O. Innovative methods of managing consumer behaviour in the economy of impressions, or the experience economy. Econ. Ann. 2017, 165, 114–118.

- Wray, A. Communication Processes. In The Dynamics of Dementia Communication; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 137–158.

- Tseng, C.H.; Chang, K.H.; Chen, H.W. Strategic orientation, environmental management systems, and eco-innovation: Investigating the moderating effects of absorptive capacity. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12147.

- Graa, A.; Abdelhak, S. The determinants of electronic word of mouth’ influence in Algerian consumer choice: The case of restaurant industry. Acta Oeconomica Univ. Selye. 2020, 9, 35–47.

- Blok, V.; Long, T.B.; Gaziulusoy, A.I.; Ciliz, N.; Lozano, R.; Huisingh, D.; Csutora, M.; Boks, C. From best practices to bridges for a more sustainable future: Advances and challenges in the transition to global sustainable production and consumption: Introduction to the ERSCP stream of the Special volume. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 19–30.

- Lubowiecki-Vikuk, A.; Dąbrowska, A.; Machnik, A. Responsible consumer and lifestyle: Sustainability insights. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 25, 91–101.

- Szakály, Z.; Popp, J.; Kontor, E.; Kovács, S.; Peto, K.; Jasák, H. Attitudes of the Lifestyle of Health and Sustainability segment in Hungary. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1763.

- Machová, R.; Ambrus, R.; Zsigmond, T.; Bakó, F. The Impact of Green Marketing on Consumer Behavior in the Market of Palm Oil Products. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1364.

- Robinson-O’Brien, R.; Burgess-Champoux, T.; Haines, J.; Hannan, P.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Through the National School Lunch Program and the School Breakfast Program and Fruit and Vegetable Intake Among Ethnically Diverse, Low-Income Children. Wiley Online Libr. 2010, 80, 487–492.

- Sharma, A.P. Consumers’ purchase behaviour and green marketing: A synthesis, review and agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 1217–1238.

- Santos, V.; Ramos, P.; Sousa, B.; Almeida, N.; Valeri, M. Factors influencing touristic consumer behaviour. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2021.

- Lee, C.; Brennan, S.; Wyllie, J. Consumer collecting behaviour: A systematic review and future research agenda. Int. J. Consum Stud. 2021.

- Rosokhata, A.; Rahmanov, F.; Mursalov, M. Consumer behavior in digital era: Impact of Covid 19. Mark. Manag. Innov. 2021, 6718, 243–251.

- Htun, S.N.N.; Zin, T.T.; Yokota, M.; Tun, K.M.M. User-intent visual information ranking system. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 5th Global Conference on Consumer Electronics, Kyoto, Japan, 11–14 October 2016; pp. 3–4.

- Pizzi, G.; Scarpi, D.; Pichierri, M.; Vannucci, V. Virtual reality, real reactions? Comparing consumers’ perceptions and shopping orientation across physical and virtual-reality retail stores. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 96, 1–12.

- Ranasinghe, N.; Jain, P.; Karwita, S.; Do, E.Y.L. Virtual lemonade: Let’s teleport your lemonade! In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction, Yokohama, Japan, 20–23 March 2017; pp. 183–190.

- Rodriguez-Raecke, R.; Sommer, M.; Brünner, Y.F.; Müschenich, F.S.; Sijben, R. Virtual grocery shopping and cookie consumption following intranasal insulin or placebo application. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2020, 28, 495–500.

- Schnack, A.; Wright, M.J.; Holdershaw, J.L. An exploratory investigation of shopper behaviour in an immersive virtual reality store. J. Consum. Behav. 2020, 19, 182–195.

- Torrico, D.D.; Han, Y.; Sharma, C.; Fuentes, S.; Gonzalez Viejo, C.; Dunshea, F.R. Effects of context and virtual reality environments on the wine tasting experience, acceptability, and emotional responses of consumers. Foods 2020, 9, 191.

- Kim, K.J.; Lim, C.H.; Heo, J.Y.; Lee, D.H.; Hong, Y.S.; Park, K. An evaluation scheme for product–service system models: Development of evaluation criteria and case studies. Serv. Bus. 2016, 10, 507–530.

- Davis, F. A Technology Acceptance Model for Empirically Testing New End-User Information Systems: Theory and Results. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986.

- Kim, J.B. An empirical study on consumer first purchase intention in online shopping: Integrating initial trust and TAM. Electron. Commer. Res. 2012, 12, 125–150.

- Sánchez, R.; Bonillo, M.Á.I.; Taulet, A.C.; Schlesinger Díaz, M.W. Modelo integrado de antecedentes y consecuencias del valor percibido por el egresado. Rev. Venez Gerenc. 2012, 16, 519–543.

- Hopkins, C.D.; Alford, B.L. Pioneering the Development of a Scale to Measure ETailer Image. J. Internet Commer. 2005, 4, 79–99.

- Becker, G. A theory of the allocation of time. Econ. J. 1965, 75, 493–517.

- Becker, G. Tratado Sobre la Familia; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 1987.

- Becker, G. La Distribución del Tiempo: Conferencia Anual de IDELCO; Instituto de Estudios del Libre Comercio: Madrid, Spain, 1995; p. 36.

- Becker, G. A Theory of Marriage: Part I. J. Polit Econ. 1973, 81, 813–846.

- Chen, P.-T.; Hu, H.-H. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management How determinant attributes of service quality influence customer-perceived value: An empirical investigation of the Australian coffee outlet industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 22, 535–551.

- Marathe, A.; Shrivastava, A.K.; Upadhyaya, R.K. Studies on interesterified products of mustard oil. Indian J. Hosp. Pharm. 2014, 18, 17–20.

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Contemp. Sociol. 1975, 6, 244.

- Vargas Rocha, F.R.; De Esteban Curiel, J.; Luiz Rodrigo, M.C. La relación entre la confianza y el compromiso y sus efectos en la lealtad de marca. Rev. Metod Cuantitativos Econ. Empres. 2020, 29, 131–151.

- Sarmiento, J.R. La experiencia de la calidad de servicio online como antecedente de la satisfacción online: Estudio empírico en los sitios web de viajes. Rev. Investig. Turísticas. 2017, 30–53.

- Sasono, I.; Jubaedi, A.D.; Novitasari, D.; Wiyono, N.; Riyanto, R.; Oktabrianto, O.; Jainuri, J.; Waruwu, H. The Impact of E-Service Quality and Satisfaction on Customer Loyalty: Empirical Evidence from Internet Banking Users in Indonesia. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 465–473.

- Fang, Y.H.; Chiu, C.M.; Wang, E.T.G. Understanding customers’ satisfaction and repurchase intentions: An integration of IS success model, trust, and justice. Internet Res. 2011, 21, 479–503.

- García-Salirrosas, E.E.; Gordillo, J.M. Brand personality as a consistency factor in the pillars of csr management in the new normal. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 134.

More

Information

Subjects:

Business

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

9.5K

Entry Collection:

COVID-19

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

22 Mar 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No