Porphyromonas gingivalis is a gram-negative bacterium found in the human oral cavity and is responsible for the development of chronic periodontitis as well as neurological diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Given the significance of the roles of P. gingivalis in AD pathogenesis, it is critical to understand the underlying mechanisms of P. gingivalis-driven neuroinflammation and their contribution to neurodegeneration. Herein, we hypothesize that P. gingivalis produces secondary metabolites that may cause neurodegeneration through direct or indirect pathways mediated by microglia. To test our hypothesis, we treated human neural cells with bacterial conditioned media on our brain platforms and assessed microgliosis, astrogliosis and neurodegeneration. We found that bacteria-mediated microgliosis induced the production of nitric oxide, which causes neurodegeneration assessed with high pTau level. Our study demonstrated the elevation of detrimental protein mediators, CD86 and iNOS and the production of several pro-inflammatory markers from stimulated microglia. Through inhibition of LPS and succinate dehydrogenase in a bacterial conditioned medium, we showed a decrease in neurodegenerative microgliosis. In addition, we demonstrated the bidirectional effect of microgliosis and astrogliosis on each other exacerbating neurodegeneration. Overall, our study suggests that the mouth-brain axis may contribute to the pathogenesis of AD.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common progressive neurodegenerative disease with clinical symptoms, such as memory loss at an early stage, that lead to a decline in the ability to respond to the living environment. Approximately 130 million people worldwide are estimated to be at risk of AD in 2050 according to the World Alzheimer Report 2015. Since the discovery of AD more than 100 years ago, several pathogenic mechanisms of AD have been proposed and the most recognized hypotheses relate to two distinctive protein markers, amyloid-beta (Aβ) and tau

[1]. Moreover, oxidative stress and neuroinflammation have been proposed as the central mechanisms of neurodegeneration in AD

[2].

A number of studies have demonstrated the connection between AD and neuroinflammation

[3]. Inflammation and degeneration of brain cells that occur in the central nervous system have been linked to the accumulation of prion protein, including Aβ and pTau, which are two known markers of AD

[4]. Microglia and astrocytes are the most abundant brain immune cells and mainly contribute to neuroinflammatory processes in neurodegenerative diseases

[5]. Neuroinflammation in AD is associated with M1/M2 stage alterations in activated microglia, which are the major immune cells in the central nervous system

[6]. Activated microglia cells change their morphologies, producing several proteins, pro-inflammatory cytokines, nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species

[7].

Bacteria-mediated neuroinflammation has been considered a critical factor in neurodegeneration

[8]. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and Aβ are two well-known factors that can trigger chronic neuroinflammation, resulting in neurodegeneration related to neuronal death and astrogliosis

[9]. Several bacterial species and their metabolites are mediators of neurodegenerative diseases

[10] and, hence, the determination of specific bacterial species or bacteria-derived factors is essential to explore the role of bacteria in AD.

Porphyromonas gingivalis, commonly called gum bacteria, is an oral gram-negative anaerobe and a major pathogen of chronic periodontitis that is popular in both developed and developing countries, infecting approximately 20–50% of the global population with a high prevalence in adults and older people

[11]. In a cohort study, chronic periodontitis patients had higher risks of dementia and AD than non-infected persons, which demonstrated the correlation of AD and periodontitis

[12]. In addition, it has been reported that oral P. gingivalis treatment induced Aβ1-42 levels, which are oligomeric forms of amyloid plaques, a well-known cause of AD and that small molecules called gingipains, which are toxic proteases, are associated with AD pathology

[13]. Immunofluorescence labeling of LPS from P. gingivalis was conducted for AD brain specimens, which have contributed to understanding the relationship between gum bacteria and AD

[14]. Current approaches have only been able to determine the effect of P. gingivalis on neuronal cells, but it is not clear if bacteria damage neurons directly or indirectly through activated microglia.

Therefore, we hypothesized that metabolites from P. gingivalis may trigger microgliosis and astrogliosis, which induce neuroinflammation, leading to neurodegeneration. In this study, we investigated the inflammatory roles of bacterial conditioned media in the activation of microglia and reactive astrocytes, which causes microgliosis and astrogliosis, as defined by immunostaining against several protein markers and measuring cytokines/chemokines released from stimulated cells. Our study demonstrated neurodegeneration by direct treatment with bacteria or indirectly through microgliosis to illustrate which mediators, bacteria or activated microglia, play a priority role in neurodegeneration. We also indicated the bidirectional interaction of microgliosis and astrogliosis and assessed microglial migration in brain-on-chip. Finally, we screened new metabolites from bacterial-conditioned media (BCM) as potential factors involved in neuroinflammation and demonstrated their cellular mechanisms.

2. Oral Pathogenic Bacteria-Inducing Neurodegenerative Microgliosis in Human Neural Cell Platform

2.1. Neurodegeneration Derived from Microgliosis and Astrogliosis-Induced Bacteria

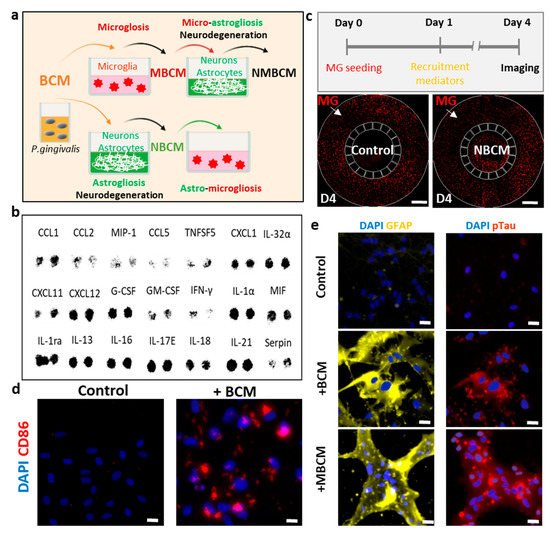

To investigate the effects of bacterial metabolites on innate immunity in the brain, we treated microglia, astrocytes and neurons isolated from patients with chronic periodontitis with P. gingivalis and assessed microgliosis, astrogliosis and neurodegeneration (Figure 1a). It should be noted that we employed two independent platforms, single-culture microglia and co-cultured neurons and astrocytes, to investigate neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration induced by BCM-stimulated microgliosis and astrogliosis.

Figure 1. Utilization of human neural cells platforms to study neurodegenerative microgliosis induced by P. gingivalis infection. (a) Schematic of experimental design for assessment of microgliosis, astrogliosis and neurodegeneration under long-term exposure to bacterial conditioned media (BCM). (b) Multiple cytokines were detected in high-concentration BCM (BCMH). (c) Representative results showing microglial recruitment on chip (Scale bar, 500 μm). (d) Representative images showing pro-inflammatory microglial marker (CD86) in control and BCM-stimulated microglia, scale bar 50 μm. (e) Representative images for reactive astrocytes (GFAP), neurodegenerative marker (pTau) of neurons/astrocytes in control, BCM and MBCM stimulation, scale bar 50 μm.

For the first platform and to investigate the effect of BCM on the microglia directly, we seeded human adult microglia (SV40) in a single-culture platform and treated them with a mixture of microglial media and BCM at a ratio of 10:1 (10 MM:1 BCML/H) for 3 days and investigated the microglial cell response. We immunostained microglia with antibodies targeting triggering receptors expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM-2), a pro-inflammatory marker (CD86) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) to determine the phenotypes of the microglia. We also validated microglial activation in response to BCM using a multicytokine assay (Figure 1b) and a migration assay in a microfluidic chip (Figure 1c). We found that multiple cytokines were present in BCM, which can be crucial mediators of microglia activation at the M1 state. This induced CD86 level and further led to the release of more pro-inflammatory cytokines from the stimulated microglia. Our study demonstrated the pro-inflammatory activity of BCM characterized by strong level of the CD86 marker, which illustrated that P. gingivalis can stimulate the M1 activation state of microglia (Figure 1d).

To test the indirect pathways, bacterial and stimulated-microglial conditioned media (BCML/H and MBCML/H) were employed to investigate if P. gingivalis could cause neurodegeneration directly from BCM or indirectly with microglia as an intermediate. Human neural progenitor cells (ReN) were differentiated for 21 days in neural media (NM) and treated with four different conditions, including BCML/H and MBCML/H. We labeled each media mixed with neural media and the BCML/H in the ratio of 100:1 as [100 NM:1 BCML/H] and MBCML/H 10:1 as [10 NM:1 MBCML/H] (Figure 1a). Stimulated microglial-conditioned media induced astrogliosis and neurodegeneration, as indicated by the induced level of the reactive astrocyte marker (GFAP) and neurodegenerative marker (pTau) (Figure 1e). Our results suggest that microglia are an important intermediate in neurodegeneration triggered by P. gingivalis.

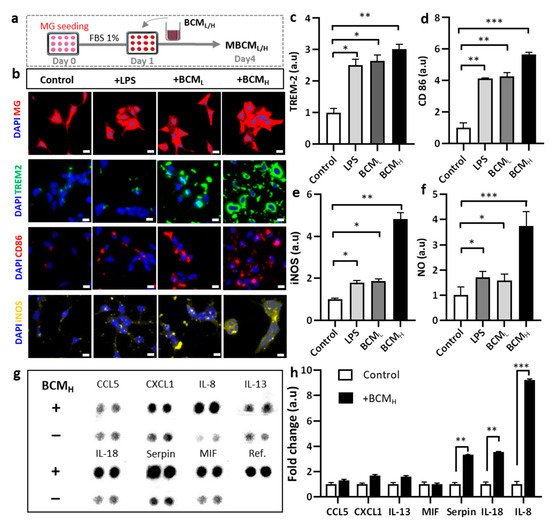

2.2. Bacterial Conditioned Media Induced Microglial Inflammatory Responses

We investigated the microglial phenotype in response to BCM. Microglial responses to LPS, BCM

L and BCM

H were assessed, as shown in

Figure 2a. We first investigated the initial response of microglia to BCM by monitoring morphological changes. LPS was used as a positive control because it is known to strongly stimulate microglia

[15]. Our data showed that morphological changes were observed in non-stimulated migroglia and LPS-/BCML-/H-stimulated cells. We also observed significant aggregation of the cells treated with LPS and BCM

L/H, compared with the non-treated cells (

Figure 2b). To further validate microglial activation in response to BCM, microglia were treated with BCM and immunostained with phenotypic markers of disease associated microglia (TREM-2) and M1 type microglia (CD86) (

Figure 2b). The bacterial and LPS-stimulated microglia expressed increased TREM-2 levels, compared with non-stimulated cells. In particular, the TREM-2 levels in LPS-, BCM

L- and BCMH-stimulated cells were almost 2.5-fold, 2.7-fold and 3-fold greater than that in the control, respectively (

Figure 2c). We also found that the level of CD-86 in BCM

H-, BCM

L- and LPS-treated microglia was significantly greater than that in the control cells (5-fold, 4-fold and 4-fold, respectively) (

Figure 2d). Overall, these data indicate differences in microglial phenotype and responses between the control group and LPS/BCM

L/H-stimulated microglia.

Figure 2. Assessment of neuro-inflammation trigged by bacterial conditioned media at two different concentrations. (a) Schematic diagram showing experimental timeline for neuro-inflammation assessment. (b) Morphological changes and immunostaining images against CD86, TREM-2 and iNOS markers of microglia cells treated with 10 ng/mL LPS, [1 BCML:10 MM] and [1 BCMH:10 MM] in a single-culture system at day 4, scale bar 50 um. (c–e) Quantification of TREM2, CD86 and iNOS fluorescent intensity expressed by stained microglia cells. Significant differences among BCML, BCMH and LPS treatment, compared with the control. (f) Analysis of the amount of nitric oxide released by microglia cells. (g,h) Quantification of chemokines and cytokines released in microglia-stimulated conditioned media indicated increased inflammatory response from microglia cells, compared with the control. All experiments were repeated three times independently and statistically analyzed by One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey HSD test (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001). All data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

To further confirm the phenotype of microglia involved in neurodegeneration, microglia cells were immunostained with inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and the level of nitric oxide (NO), which is defined as one of the causes of neuroinflammation was measured

[16]. We also quantified the levels of iNOS and NO and performed statistical analysis to determine statistical significance. According to the results, BCM

H-treated microglia expressed a significantly higher level of iNOS, which was 4.8-fold greater than the control and 2.5-fold greater than LPS-and BCL-treated microglia (

Figure 2e). BCM

H-stimulated microglia highly expressed NO, which was 3.7-fold, 2.2-fold and 2.4-fold higher than those in non-stimulated, LPS- and BCML-treated cells, respectively (

Figure 2f). Next, we assessed the status of microglial inflammation by measuring multiple inflammatory cytokines in the MBCM (

Figure 2g). The levels of cytokines, including IL-8, IL-18 and serpin, in BCM

H-stimulated microglia were significantly higher, at almost 7.5-fold, 3-fold and 2.8-fold, respectively, than those in non-stimulated cells (

Figure 2h). Our data suggested that BCM induced microglial pro-inflammation, which may play a detrimental role in neuroinflammation, supporting our hypothesis that BCM can trigger microgliosis during

P. gingivalis infection.

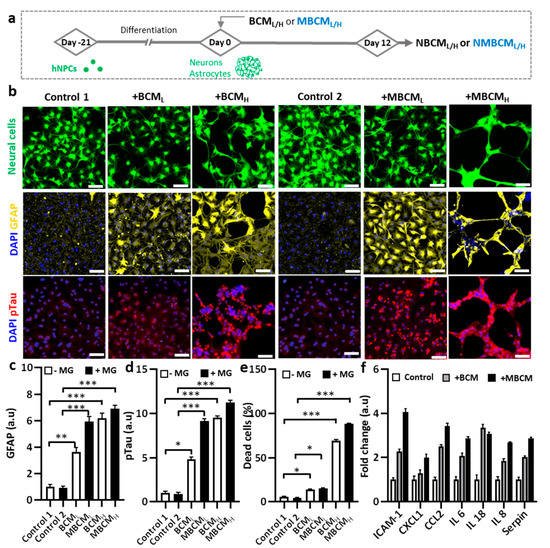

2.3. Neurodegeneration Induced by Both Microglial and Bacterial Condition Media

To demonstrate microgliosis-mediated neurodegeneration, co-cultured neurons and astrocyte-derived hNPCs were exposed to either BCML/H or MBCML/H (Figure 3a). We found notable morphological changes in the co-cultured neurons and astrocytes stimulated by BCML/H or MBCML/H, compared with the non-treated cells (Figure 3b). In addition, GFAP levels increased in astrocytes stimulated by both BCML/H and MBCML/H, representing the BCM-and MBCM-induced reactive astrocytes. We found that BCMH-stimulated microglial-derived media showed nearly 9-fold higher GFAP level, compared with the controls, while the BCMH-directed treatment caused a 7-fold increase in GFAP level (Figure 3c). In addition, treatment with MBCML and MBCMH slightly increased GFAP level.

Figure 3. Neurodegeneration initiated by different bacteria-conditioned media (BCML/H) and microglia-derived media containing bacterial metabolites (MBCML/H). (a) Schematic diagram showing experimental timeline for astrogliosis and neurodegeneration. (b) Morphological changes in neurons/astrocytes (green) treated with bacterial conditioned media and microglia-stimulated conditioned media. Fluorescent images of GFAP and pTau staining of neurons/astrocytes after 12-day exposure. Scale bar, 100 μm. (c,d) Quantification of GFAP and pTau level in neurons/astrocytes. (e) Neural cells loss is quantified by measuring dead cell ratio. (f) Quantification of cytokines from astrocyte conditioned media. All experiments were repeated three times independently and statistically analyzed by One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey HSD test (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001). All data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

We next investigated the effect of conditioned media on neuronal cells. We found that neurons treated with MBCM

L/H exhibited higher pTau level than those treated with BCM

L/H treatment, indicating microgliosis and a higher AD risk

[17]. Compared with non-stimulated neural cells, treatment with MBCM

H and BCM

H increased pTau levels by approximately 11.25 folds and 9.5 folds, respectively (

Figure 3d). Our results demonstrated the association of MBCM

L and BCM

L with increase in AD risk, characterized by high pTau level. To determine cell viability, propidium iodide (PI) was used to stain dead cells, while DAPI was used to stain the nuclei of both dead and live cells. We then determined the population of dead cells (

Figure 3e). The population of neurons and astrocytes treated with BCM and MBCM significantly decreased and the treatment with microglial conditioned media led to approximately 90% neuronal cell loss and the BCM

H treatment resulted in almost 70% neuronal death. Moreover, the low concentration of bacterial and stimulated microglia-conditioned media (BCM

L and MBCM

L) reduced the population by 15%. Both low and high concentrations of BCM and MBCM increased cell death of astrocytes and neurons, while BCM

H and MBCM

H were much more detrimental to the neurons/astrocyte population at high concentrations than at low concentrations. Taken together, our results indicate that neurodegenerative microgliosis is caused by bacterial infection in AD.

Next, we performed multiple cytokine detection to identify the cytokines in stimulated neurons/astrocyte-conditioned media. Conditioned media from non-stimulated, BCMH-treated and MBCMH-stimulated neurons/astrocytes were utilized for the detection. Multiple cytokines were detected, including CXCL1, IL-8, IL-6, Serpin, IL-18, CCL2 and ICAM-1 and the level of cytokines was normalized to that in non-stimulated cells. The BCMH-treated cells generated more cytokines than the MBCMH cells, excluding IL-18 (Figure 3f). CCL2 was ranked second in the level, at more than 3.5-fold for BCMH and 2.5-fold for MBCMH, compared with non-stimulated cells, which clarified why NBCMH recruited more microglia into the central chamber than NMBCH.

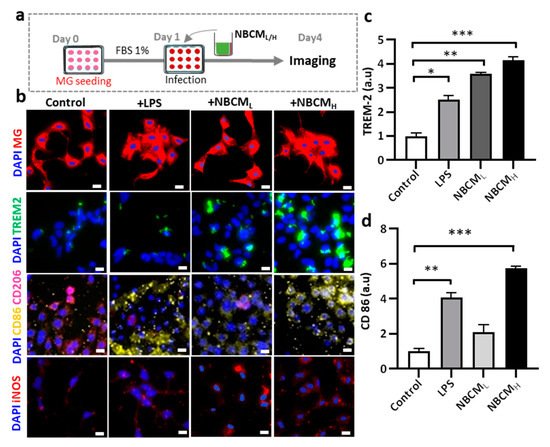

2.4. Investigating the Interaction of Astrogliosis and Microgliosis

After inducing neurodegeneration with BCML/H and MBCML/H, we hypothesized that neuron-glia might have bidirectional influences on each other. Microgliosis involves the induction of loss of neurons/astrocytes (Figure 3) and astrogliosis may cause the activation of microglia, which means that microgliosis and astrogliosis may occur at the same time during infection and induce each other.

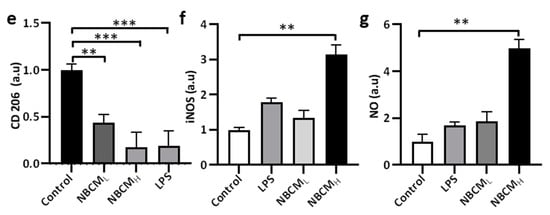

To test our hypothesis, conditioned media of neurons/astrocytes treated with BCMH or MBCMH were harvested (NBCML/H or NMBCML/H) and treated with the single-culture microglia (Figure 4a). To investigate the activation of microglia by astrogliosis, we monitored the morphological changes in microglia and the level of critical proteins representing microglial activation. Our results showed changes in the morphology of microglia treated with LPS and NBCML/H, compared with the control. Next, microglia cells were stained against TREM-2, CD86, CD206 and iNOS to determine if stimulated microglia would exhibit a pro- or anti-inflammatory phenotype (Figure 4b). We found that microglia treated with NBCM showed higher TREM-2 level than those treated with LPS (Figure 4c). Interestingly, microglia treated with neurons/astrocyte-conditioned media co-expressed CD86 and CD206. NBCMH-treated microglia cells showed a higher level of CD86 protein than LPS-treated and non-stimulated microglial cells, but at low concentration, a low CD86 level, which was not statistically different from that of non-stimulated cells, was observed (Figure 4d). In particular, the NBCMH-stimulated microglia showed a 1.4-fold increase in CD86 level, in comparison with LPS-treated microglia, but a 5.7-fold increase, in comparison with non-stimulated microglia. With regard to the effect of low and high concentrations, NBCMH caused a 2.8-fold increase in CD86 level, compared with NBCML. Consistently, non-stimulated microglia showed higher level of anti-inflammatory protein markers than the treated cells, while microglia stimulated with LPS showed the lowest level of CD206 (Figure 4e). The level of CD206 in NBCML-treated microglia cells was 1.4-fold lower than that in non-stimulated cells. LPS and NBCMH caused a decrease in CD206 level, which was almost 5-fold lower than that in the control. Briefly, NBCMH induced pro-inflammatory protein markers better than NBCML, but greater anti-inflammatory activity was induced at the low concentration of conditioned media. In addition, microglia treated with neurons/astrocyte conditioned media significantly activated the iNOS pathway, compared with non-stimulated cells; in particular, NBCMH showed the best efficacy in the activation of iNOS, which was 3.2-fold higher than that of the control (Figure 4f). Consistently, NBCMH-treated microglia generated higher levels of NO than NBCMH-treated (2-fold) and LPS-treated cells (2.4-fold) (Figure 4g). Overall, our data showed that BCM-stimulated astrogliosis could also induce microglial activation.

Figure 4. Neuron-glia interaction assessed by BCML/H- and MBCML/H-stimulated neurons/astrocytes conditioned media. (a) Schematic diagram showing experimental timeline for investigating astrogliosis and microgliosis. (b) Morphological changes, immunostaining of SV40 microglia cell treated with 10 ng/mL LPS, [1 NBCM:10 MM] and [1 NMBCM:10 MM] against TREM-2, CD86, CD206 and iNOS in a single culture system. (c–f) Quantification of TREM-2, CD86, CD206 and iNOS in stimulated microglia. (g) Analysis of nitric oxide released by stimulated microglia. All experiments were repeated three times independently and statistically analyzed by One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey HSD test (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001). All data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).