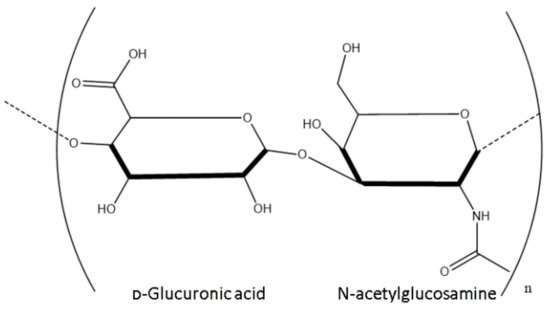

Hyaluronic acid (HA) is a naturally occurring mucopolysaccharide that belongs to a group of heteropolysaccharides referred to as glycosaminoglycans (GAGs). Mucopolysaccharides are long chain sugar molecules commonly found in mucous or joint fluid in the body. Endogenous HA is found throughout the human body in the vitreous humour, joints, umbilical cord, connective tissue, and skin. Native HA, extracted from animal sources such as rooster comb or from biotechnological processes such as Lactobacillus fermentation, has a major caveat in that it is readily degraded by the body. Through modification, however, HA displays resistance to degradation whilst also enabling conjugation or cross-linking with a variety of molecules. This freely accessible natural polysaccharide has a wide range of applications due to its unique physicochemical and bioactive properties, which will be explored in depth throughout this review. Furthermore, HA is biocompatible and biodegradable, making it a safe biomaterial for biomedical applications such as biomedical engineering, as well as finding applications in the cosmetics industry, wound healing, and drug delivery.

- naturally-occurring polymers

- polysaccharide

- immunotherapies

- heteropolysaccharides

- hyaluronic acid

- biomaterials

- drug-delivery

1. Physicochemical Properties of Hyaluronic Acid (HA)

Structure

1.1. Structure

Molecular Weight

1.2. Molecular Weight

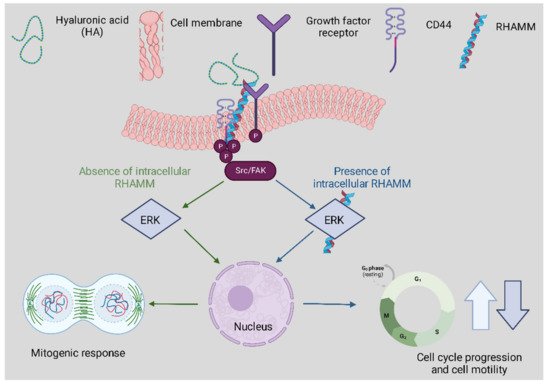

2. Endogenous Bioactive Properties

Receptor Interactions

3. Synthesis

Microbial Synthesis

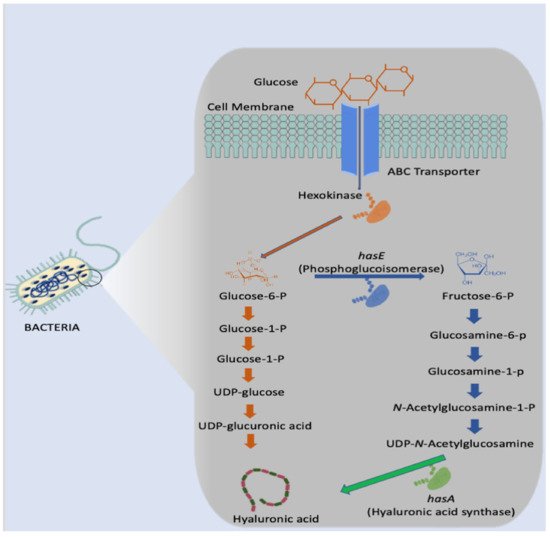

3.1. Microbial Synthesis

Animal Synthesis

3.2. Animal Synthesis

4. Degradation

Enzymatic Degradation

5. Modification

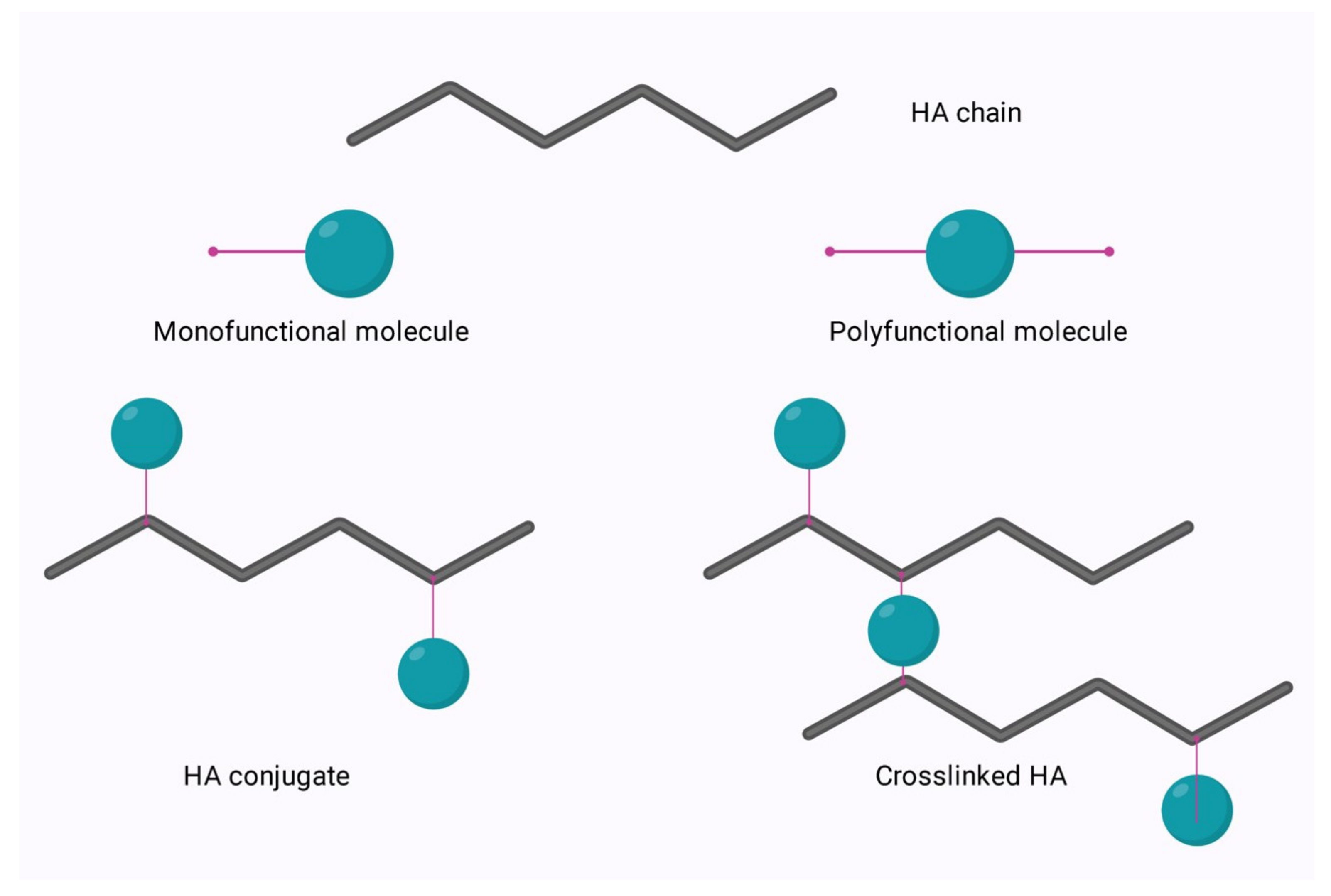

Native hyaluronic acid (HA) has found a broad range of applications in areas such as ophthalmology and cosmetics due to its unique physicochemical characteristics. However, this endogenous polymer is readily degraded in the body by the enzyme, hyaluronidase. The rate of degradation of native HA stifles its applicability to bioengineering applications or those which require a longer residence time in the body. To enable expansion of the applications of this polysaccharide, it can be modified to allow for cross-linking and engineering, to tailor the degradation profile in vivo, improve cell attachment, and enable conjugation. The relatively simple structure of HA allows for ease of modification of its two main functional groups- the hydroxyl and the carboxyl groups. Additionally, further synthetic modifications may be performed following the deacetylation of the acetamide group, which can allow for the recovery of amino functionalities. Regardless of the functional group to be modified, there are two options for modification; crosslinking or conjugation as outlined in Figure 1 below.

Conjugation is modification via the grafting of a molecule onto the HA chain by a covalent bond, whereas crosslinking involves the formation of a matrix of polyfunctional compounds which link chains of native or conjugated HA via two or more covalent bonds [58][59]. Crosslinking can be performed on either native HA or conjugated HA. This is of particular interest in the area of bioconjugation. Bioconjugation is the act of conjugating peptides or proteins to a natural polymer to increase efficacy. Previously, this was performed using polyethene glycol (PEG). PEGylation was found to increase the effectiveness of drugs by reducing renal clearance, enzymatic degradation, and immunogenicity in vivo. However, repeated injection of PEGylated liposomes has been found to cause accelerated blood clearance and trigger hypersensitivity [60]. Thus, HA is now under investigation as a plausible alternative [61]. Conjugation allows for crosslinking with a variety of molecules to enable the improvement of drug carrier systems with optimised properties. The crosslinking of HA allows for fine-tuning of many characteristics, such as mechanical, rheological, and swelling properties, and protects the polymer from enzymatic degradation to allow for longer residence time at the required treatment site. The process of bioconjugation and crosslinking has found applications in medicine, aesthetics, and bioengineering to treat various ailments. The different approaches and applications of functionalisation have been discussed in great detail by Sanjay Tiwari and Pratap Bahadur (2019) [62], so only a brief overview of hydroxyl and carboxyl group chemical modifications will be discussed.Modification of HA via the Hydroxyl Group

Modification of HA via the Carboxyl Group

6. Immunomodulation

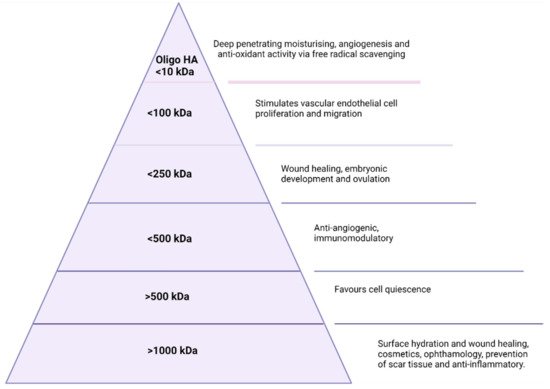

The principal function of the immune system is defence, either against foreign matter, including pathogens, or against disease, including cancer. The complexity of the immune system occurs when the immune response either fails to respond to a pathogen or is over-exasperated. Interventions such as vaccines can improve the immune response. Steroids or anti-inflammatory medications can reduce hyper-inflammation. Inflammation is a key, protective immunological function. If not appropriately controlled, it can cause harm to the host and lead to pathologies. Inflammation is linked to several chronic diseases. With increasing numbers of autoimmune conditions and infectious agents, molecules that interact positively with the immune system are always in demand. Hyaluronic acid (HA) is a natural polysaccharide that is abundant in the human body and can be obtained through animal extraction or bacterial fermentation. This unique biopolymer has been shown to have contrasting immune effects depending on the molecular weight of the molecule. Both low molecular weight and high molecular weight HA have found uses as moderators of inflammation and immune response which lends this molecule to a host of applications from wound repair to vaccine adjuvants. Herein, it seeks to evaluate the immunomodulatory uses and potentials of hyaluronic acid.

The Role of Hyaluronic Acid in Inflammation

The Importance of Molecular Weight in HA Immunomodulation

References

- Selyanin, M.A.; Boykov, P.Y.; Khabarov, V.N.; Polyak, F. Hyaluronic Acid: Preparation, Properties, Application in Biology and Medicine; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]Selyanin, M.A.; Boykov, P.Y.; Khabarov, V.N.; Polyak, F. Hyaluronic Acid: Preparation, Properties, Application in Biology and Medicine; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2015.

- Meyer, K.; Palmer, J. The polysaccharide of the vitreous humor. J. Biol. Chem. 1934, 107, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Ogston, A.G.; Stanier, J.E. The physiological function of hyaluronic acid in synovial fluid; viscous, elastic and lubricant properties. J. Physiol. 1953, 119, 244–252.

- Necas, J.; Bartosikova, L.; Brauner, P.; Kolar, J.J. Hyaluronic acid (hyaluronan): A review. Vet. Med. 2018, 53, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Snetkov, P.; Zakharova, K.; Morozkina, S.; Olekhnovich, R.; Uspenskaya, M. Hyaluronic Acid: The influence of molecular weight on structural, physical, physico-chemical, and degradable properties of biopolymer. Polymers 2020, 12, E1800.

- Tanwar, J.; Hungund, S.A. Hyaluronic acid: Hope of light to black triangles. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2016, 6, 497–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Amorim, S.; da Costa, D.S.; Freitas, D.; Reis, C.A.; Reis, R.L.; Pashkuleva, I.; Pires, R.A. Molecular weight of surface immobilized hyaluronic acid influences CD44-mediated binding of gastric cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16058. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-34445-0 (accessed on 8 June 2022).

- Balazs, E.A.; Laurent, T.C.; Jeanloz, R.W. Nomenclature of hyaluronic acid. Biochem. J. 1986, 235, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Gruber, J.V.; Holtz, R.; Riemer, J. Hyaluronic acid (HA) stimulates the in vitro expression of CD44 proteins but not HAS1 proteins in normal human epidermal keratinocytes (NHEKs) and is HA molecular weight dependent. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 1193–1198.

- Ogston, A.G.; Stanier, J.E. The physiological function of hyaluronic acid in synovial fluid; viscous, elastic and lubricant properties. J. Physiol. 1953, 119, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Abatangelo, G.; Vindigni, V.; Avruscio, G.; Pandis, L.; Brun, P. Hyaluronic Acid: Redefining its role. Cells 2020, 9, 1743.

- Snetkov, P.; Zakharova, K.; Morozkina, S.; Olekhnovich, R.; Uspenskaya, M. Hyaluronic Acid: The influence of molecular weight on structural, physical, physico-chemical, and degradable properties of biopolymer. Polymers 2020, 12, E1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Gao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Yang, H.; Qiu, P.; Cong, Z.; Zou, Y.; Song, L.; Guo, J.; Anastassiades, T.P. A low molecular weight hyaluronic acid derivative accelerates excisional wound healing by modulating pro-inflammation, promoting epithelialization and neovascularization, and remodeling collagen. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3722.

- Amorim, S.; da Costa, D.S.; Freitas, D.; Reis, C.A.; Reis, R.L.; Pashkuleva, I.; Pires, R.A. Molecular weight of surface immobilized hyaluronic acid influences CD44-mediated binding of gastric cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16058. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-34445-0 (accessed on 8 June 2022).Wolf, K.J.; Kumar, S. Hyaluronic Acid: Incorporating the bio into the material. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 5, 3753–3765.

- Gruber, J.V.; Holtz, R.; Riemer, J. Hyaluronic acid (HA) stimulates the in vitro expression of CD44 proteins but not HAS1 proteins in normal human epidermal keratinocytes (NHEKs) and is HA molecular weight dependent. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 1193–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Kim, H.; Shin, M.; Han, S.; Kwon, W.; Hahn, S.K. Hyaluronic acid derivatives for translational medicines. Biomacromolecules 2019, 20, 2889–2903.

- Abatangelo, G.; Vindigni, V.; Avruscio, G.; Pandis, L.; Brun, P. Hyaluronic Acid: Redefining its role. Cells 2020, 9, 1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Misra, S.; Hascall, V.C.; Markwald, R.R.; Ghatak, S. Interactions between hyaluronan and its receptors (CD44, RHAMM) regulate the activities of inflammation and cancer. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 201. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fimmu.2015.00201 (accessed on 8 June 2022).

- Gao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Yang, H.; Qiu, P.; Cong, Z.; Zou, Y.; Song, L.; Guo, J.; Anastassiades, T.P. A low molecular weight hyaluronic acid derivative accelerates excisional wound healing by modulating pro-inflammation, promoting epithelialization and neovascularization, and remodeling collagen. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Balazs, E.A.; Watson, D.; Duff, I.F.; Roseman, S. Hyaluronic acid in synovial fluid. I. Molecular parameters of hyaluronic acid in normal and arthritic human fluids. Arthritis Rheum. 1967, 10, 357–376.

- Wolf, K.J.; Kumar, S. Hyaluronic Acid: Incorporating the bio into the material. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 5, 3753–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Bjelle, A.; Andersson, T.; Granath, K. Molecular weight distribution of hyaluronic acid of human synovial fluid in rheumatic diseases. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 1983, 12, 133–138.

- Kim, H.; Shin, M.; Han, S.; Kwon, W.; Hahn, S.K. Hyaluronic acid derivatives for translational medicines. Biomacromolecules 2019, 20, 2889–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Tammi, R.; Ågren, U.M.; Tuhkanen, A.-L.; Tammi, M. Hyaluronan metabolism in skin. Prog. Histochem. Cytochem. 1994, 29, 727459.

- Misra, S.; Hascall, V.C.; Markwald, R.R.; Ghatak, S. Interactions between hyaluronan and its receptors (CD44, RHAMM) regulate the activities of inflammation and cancer. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 201. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fimmu.2015.00201 (accessed on 8 June 2022).Papakonstantinou, E.; Roth, M.; Karakiulakis, G. Hyaluronic acid: A key molecule in skin aging. Derm.-Endocrinol. 2012, 4, 253–258.

- Balazs, E.A.; Watson, D.; Duff, I.F.; Roseman, S. Hyaluronic acid in synovial fluid. I. Molecular parameters of hyaluronic acid in normal and arthritic human fluids. Arthritis Rheum. 1967, 10, 357–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Amandusova, A.K.; Saveleva, K.R.; Morozov, A.V.; Shelekhova, V.A.; Persanova, L.V.; Polyakov, S.V.; Shestakov, V.N. Physical and chemical properties and quality control methods of hyaluronic acid. Drug Dev. Regist. 2020, 9, 136–140.

- Bjelle, A.; Andersson, T.; Granath, K. Molecular weight distribution of hyaluronic acid of human synovial fluid in rheumatic diseases. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 1983, 12, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Garg, H.G.; Hales, C.A. Chemistry and Biology of Hyaluronan, 1st ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; Available online: http://gen.lib.rus.ec/book/index.php?md5=f3fdc80834f8d3a057180095f4b5e6b5 (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Tammi, R.; Ågren, U.M.; Tuhkanen, A.-L.; Tammi, M. Hyaluronan metabolism in skin. Prog. Histochem. Cytochem. 1994, 29, 727459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Tengblad, A.; Laurent, U.B.G.; Lilja, K.; Cahill, R.N.P.; Engström-Laurent, A.; Fraser, J.R.R.; Hansson, H.E.; Laurent, T.C. Concentration and relative molecular mass of hyaluronate in lymph and blood. Biochem. J. 1986, 236, 521–525.

- Papakonstantinou, E.; Roth, M.; Karakiulakis, G. Hyaluronic acid: A key molecule in skin aging. Derm.-Endocrinol. 2012, 4, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Laurent, T.C.; Lilja, K.; Brunnberg, L.; Engström-Laurent, A.; Laurent, U.B.; Lindqvist, U.; Murata, K.; Ytterberg, D. Urinary excretion of hyaluronan in man. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. 1987, 47, 793–799.

- Garg, H.G.; Hales, C.A. Chemistry and Biology of Hyaluronan, 1st ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; Available online: http://gen.lib.rus.ec/book/index.php?md5=f3fdc80834f8d3a057180095f4b5e6b5 (accessed on 21 July 2021).Harrer, D.; Armengol, E.S.; Friedl, J.D.; Jalil, A.; Jelkmann, M.; Leichner, C.; Laffleur, F. Is hyaluronic acid the perfect excipient for the pharmaceutical need? Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 601, 120589.

- Tengblad, A.; Laurent, U.B.G.; Lilja, K.; Cahill, R.N.P.; Engström-Laurent, A.; Fraser, J.R.R.; Hansson, H.E.; Laurent, T.C. Concentration and relative molecular mass of hyaluronate in lymph and blood. Biochem. J. 1986, 236, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Turathum, B.; Gao, E.-M.; Chian, R.-C. The function of cumulus cells in oocyte growth and maturation and in subsequent ovulation and fertilization. Cells 2021, 10, 2292.

- Laurent, T.C.; Lilja, K.; Brunnberg, L.; Engström-Laurent, A.; Laurent, U.B.; Lindqvist, U.; Murata, K.; Ytterberg, D. Urinary excretion of hyaluronan in man. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. 1987, 47, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Buffa, R.; Nešporová, K.; Basarabová, I.; Halamková, P.; Svozil, V.; Velebný, V. Synthesis and study of branched hyaluronic acid with potential anticancer activity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 223, 15047.

- Harrer, D.; Armengol, E.S.; Friedl, J.D.; Jalil, A.; Jelkmann, M.; Leichner, C.; Laffleur, F. Is hyaluronic acid the perfect excipient for the pharmaceutical need? Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 601, 120589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Pedron, S.; Wolter, G.L.; Chen, J.-W.E.; Laken, S.E.; Sarkaria, J.N.; Harley, B.A.C. Hyaluronic acid-functionalized gelatin hydrogels reveal extracellular matrix signals temper the efficacy of erlotinib against patient-derived glioblastoma specimens. Biomaterials 2019, 219, 119371.

- Turathum, B.; Gao, E.-M.; Chian, R.-C. The function of cumulus cells in oocyte growth and maturation and in subsequent ovulation and fertilization. Cells 2021, 10, 2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Graça, M.F.P.; Miguel, S.P.; Cabral, C.S.D.; Correia, I.J. Hyaluronic acid—Based wound dressings: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 241, 116364.

- Buffa, R.; Nešporová, K.; Basarabová, I.; Halamková, P.; Svozil, V.; Velebný, V. Synthesis and study of branched hyaluronic acid with potential anticancer activity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 223, 15047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Essendoubi, M.; Gobinet, C.; Reynaud, R.; Angiboust, J.F.; Manfait, M.; Piot, O. Human skin penetration of hyaluronic acid of different molecular weights as probed by Raman spectroscopy. Skin Res. Technol. 2016, 22, 55–62.

- Pedron, S.; Wolter, G.L.; Chen, J.-W.E.; Laken, S.E.; Sarkaria, J.N.; Harley, B.A.C. Hyaluronic acid-functionalized gelatin hydrogels reveal extracellular matrix signals temper the efficacy of erlotinib against patient-derived glioblastoma specimens. Biomaterials 2019, 219, 119371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Zerbinati, N.; Sommatis, S.; Maccario, C.; Capillo, M.C.; Grimaldi, G.; Alonci, G.; Protasoni, M.; Rauso, R.; Mocchi, R. Toward physicochemical and rheological characterization of different injectable hyaluronic acid dermal fillers cross-linked with polyethylene glycol diglycidyl ether. Polymers 2021, 13, 948.

- Graça, M.F.P.; Miguel, S.P.; Cabral, C.S.D.; Correia, I.J. Hyaluronic acid—Based wound dressings: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 241, 116364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Saha, I.; Rai, V.K. Hyaluronic acid based microneedle array: Recent applications in drug delivery and cosmetology. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 267, 118168.

- Essendoubi, M.; Gobinet, C.; Reynaud, R.; Angiboust, J.F.; Manfait, M.; Piot, O. Human skin penetration of hyaluronic acid of different molecular weights as probed by Raman spectroscopy. Skin Res. Technol. 2016, 22, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Katsumi, H.; Liu, S.; Tanaka, Y.; Hitomi, K.; Hayashi, R.; Hirai, Y.; Kusamori, K.; Quan, Y.S.; Kamiyama, F.; Sakane, T.; et al. Development of a novel self-dissolving microneedle array of alendronate, a nitrogen-containing bisphosphonate: Evaluation of transdermal absorption, safety, and pharmacological effects after application in rats. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 101, 3230–3238.

- Zerbinati, N.; Sommatis, S.; Maccario, C.; Capillo, M.C.; Grimaldi, G.; Alonci, G.; Protasoni, M.; Rauso, R.; Mocchi, R. Toward physicochemical and rheological characterization of different injectable hyaluronic acid dermal fillers cross-linked with polyethylene glycol diglycidyl ether. Polymers 2021, 13, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Liu, S.; Jin, M.N.; Quan, Y.S.; Kamiyama, F.; Katsumi, H.; Sakane, T.; Yamamoto, A. The development and characteristics of novel microneedle arrays fabricated from hyaluronic acid, and their application in the transdermal delivery of insulin. J. Control. Release 2012, 161, 933–941.

- Saha, I.; Rai, V.K. Hyaluronic acid based microneedle array: Recent applications in drug delivery and cosmetology. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 267, 118168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Vasvani, S.; Kulkarni, P.; Rawtani, D. Hyaluronic acid: A review on its biology, aspects of drug delivery, route of administrations and a special emphasis on its approved marketed products and recent clinical studies. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 151, 1012–1029.

- Katsumi, H.; Liu, S.; Tanaka, Y.; Hitomi, K.; Hayashi, R.; Hirai, Y.; Kusamori, K.; Quan, Y.S.; Kamiyama, F.; Sakane, T.; et al. Development of a novel self-dissolving microneedle array of alendronate, a nitrogen-containing bisphosphonate: Evaluation of transdermal absorption, safety, and pharmacological effects after application in rats. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 101, 3230–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Rangasami, V.K.; Samanta, S.; Parihar, V.S.; Asawa, K.; Zhu, K.; Varghese, O.P.; Teramura, Y.; Nilsson, B.; Hilborn, J.; Harris, R.A.; et al. Harnessing hyaluronic acid-based nanoparticles for combination therapy: A novel approach for suppressing systemic inflammation and to promote antitumor macrophage polarization. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 254, 117291.

- Liu, S.; Jin, M.N.; Quan, Y.S.; Kamiyama, F.; Katsumi, H.; Sakane, T.; Yamamoto, A. The development and characteristics of novel microneedle arrays fabricated from hyaluronic acid, and their application in the transdermal delivery of insulin. J. Control. Release 2012, 161, 933–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Schumann, J.; Stanko, K.; Schliesser, U.; Appelt, C.; Sawitzki, B. Differences in CD44 surface expression levels and function discriminates IL-17 and IFN-γ producing helper T Cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132479.

- Vasvani, S.; Kulkarni, P.; Rawtani, D. Hyaluronic acid: A review on its biology, aspects of drug delivery, route of administrations and a special emphasis on its approved marketed products and recent clinical studies. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 151, 1012–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Hanoux, V.; Eguida, J.; Fleurot, E.; Levallet, J.; Bonnamy, P.-J. Increase in hyaluronic acid degradation decreases the expression of estrogen receptor alpha in MCF7 breast cancer cell line. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2018, 476, 185–197.

- Rangasami, V.K.; Samanta, S.; Parihar, V.S.; Asawa, K.; Zhu, K.; Varghese, O.P.; Teramura, Y.; Nilsson, B.; Hilborn, J.; Harris, R.A.; et al. Harnessing hyaluronic acid-based nanoparticles for combination therapy: A novel approach for suppressing systemic inflammation and to promote antitumor macrophage polarization. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 254, 117291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Weigel, P.H.; DeAngelis, P.L. Hyaluronan synthases: A decade-plus of novel glycosyltransferases. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 36777–36781.

- Schumann, J.; Stanko, K.; Schliesser, U.; Appelt, C.; Sawitzki, B. Differences in CD44 surface expression levels and function discriminates IL-17 and IFN-γ producing helper T Cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132479. [Google Scholar]Weigel, P.H.; Hascall, V.C.; Tammi, M. Hyaluronan synthases. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 13997-4000.

- Hanoux, V.; Eguida, J.; Fleurot, E.; Levallet, J.; Bonnamy, P.-J. Increase in hyaluronic acid degradation decreases the expression of estrogen receptor alpha in MCF7 breast cancer cell line. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2018, 476, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Vigetti, D.; Karousou, E.; Viola, M.; Deleonibus, S.; De Luca, G.; Passi, A. Hyaluronan: Biosynthesis and signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gen. Subj. 2014, 1840, 2452–2459.

- Weigel, P.H.; DeAngelis, P.L. Hyaluronan synthases: A decade-plus of novel glycosyltransferases. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 36777–36781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Yao, Z.-Y.; Qin, J.; Gong, J.-S.; Ye, Y.-H.; Qian, J.-Y.; Li, H.; Xu, Z.H.; Shi, J.S. Versatile strategies for bioproduction of hyaluronic acid driven by synthetic biology. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 264, 118015.

- Weigel, P.H.; Hascall, V.C.; Tammi, M. Hyaluronan synthases. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 13997-4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Sze, J.H.; Brownlie, J.C.; Love, C.A. Biotechnological production of hyaluronic acid: A mini review. 3 Biotech 2016, 6, 67.

- Vigetti, D.; Karousou, E.; Viola, M.; Deleonibus, S.; De Luca, G.; Passi, A. Hyaluronan: Biosynthesis and signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gen. Subj. 2014, 1840, 2452–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Sheng, J.; Ling, P.; Wang, F. Constructing a recombinant hyaluronic acid biosynthesis operon and producing food-grade hyaluronic acid in Lactococcus lactis. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 42, 197–206.

- Yao, Z.-Y.; Qin, J.; Gong, J.-S.; Ye, Y.-H.; Qian, J.-Y.; Li, H.; Xu, Z.H.; Shi, J.S. Versatile strategies for bioproduction of hyaluronic acid driven by synthetic biology. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 264, 118015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Tien, J.Y.L.; Spicer, A.P. Three vertebrate hyaluronan synthases are expressed during mouse development in distinct spatial and temporal patterns. Dev. Dyn. 2005, 233, 130–141.

- Sheng, J.; Ling, P.; Wang, F. Constructing a recombinant hyaluronic acid biosynthesis operon and producing food-grade hyaluronic acid in Lactococcus lactis. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 42, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Toole, B.P. Hyaluronan in morphogenesis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2001, 12, 79–87.

- Tien, J.Y.L.; Spicer, A.P. Three vertebrate hyaluronan synthases are expressed during mouse development in distinct spatial and temporal patterns. Dev. Dyn. 2005, 233, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Takayama, Y. Role of hyaluronan in wound healing. In Lactoferrin and Its Role in Wound Healing; Takayama, Y., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 25–42.

- Toole, B.P. Hyaluronan in morphogenesis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2001, 12, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Schulz, T.; Schumacher, U.; Prehm, P. Hyaluronan export by the ABC transporter MRP5 and its modulation by intracellular cGMP. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 20999–21004.

- Takayama, Y. Role of hyaluronan in wound healing. In Lactoferrin and Its Role in Wound Healing; Takayama, Y., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Lee, W.-L.; Lee, F.-K.; Wang, P.-H. Application of hyaluronic acid in patients with interstitial cystitis. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2021, 84, 341–343.

- Schulz, T.; Schumacher, U.; Prehm, P. Hyaluronan export by the ABC transporter MRP5 and its modulation by intracellular cGMP. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 20999–21004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Manfrão-Netto, J.H.; Queiroz, E.B.; de Oliveira Junqueira, A.C.; Gomes, A.M.; Gusmao de Morais, D.; Paes, H.C.; Parachin, N.S. Genetic strategies for improving hyaluronic acid production in recombinant bacterial culture. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 132, 822–840.

- Lee, W.-L.; Lee, F.-K.; Wang, P.-H. Application of hyaluronic acid in patients with interstitial cystitis. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2021, 84, 341–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Chen, X.; Sun-Waterhouse, D.; Yao, W.; Li, X.; Zhao, M.; You, L. Free radical-mediated degradation of polysaccharides: Mechanism of free radical formation and degradation, influence factors and product properties. Food Chem. 2021, 365, 130524.

- Manfrão-Netto, J.H.; Queiroz, E.B.; de Oliveira Junqueira, A.C.; Gomes, A.M.; Gusmao de Morais, D.; Paes, H.C.; Parachin, N.S. Genetic strategies for improving hyaluronic acid production in recombinant bacterial culture. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 132, 822–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Fraser, J.R.E.; Laurent, T.C.; Laurent, U.B.G. Hyaluronan: Its nature, distribution, functions and turnover. J. Intern. Med. 1997, 242, 27–33.

- Chen, X.; Sun-Waterhouse, D.; Yao, W.; Li, X.; Zhao, M.; You, L. Free radical-mediated degradation of polysaccharides: Mechanism of free radical formation and degradation, influence factors and product properties. Food Chem. 2021, 365, 130524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Wongprasert, P.; Dreiss, C.A.; Murray, G. Evaluating hyaluronic acid dermal fillers: A critique of current characterization methods. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15453.

- Fraser, J.R.E.; Laurent, T.C.; Laurent, U.B.G. Hyaluronan: Its nature, distribution, functions and turnover. J. Intern. Med. 1997, 242, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]De Paiva, W.K.V.; Medeiros, W.R.; Assis, C.F.; Dos Santos, E.S.; de Sousa Júnior, F.C. Physicochemical characterization and in vitro antioxidant activity of hyaluronic acid produced by Streptococcus zooepidemicus CCT 7546. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2022, 52, 234–243.

- Wongprasert, P.; Dreiss, C.A.; Murray, G. Evaluating hyaluronic acid dermal fillers: A critique of current characterization methods. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Kaul, A.; Short, W.D.; Wang, X.; Keswani, S.G. Hyaluronidases in human diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3204.

- De Paiva, W.K.V.; Medeiros, W.R.; Assis, C.F.; Dos Santos, E.S.; de Sousa Júnior, F.C. Physicochemical characterization and in vitro antioxidant activity of hyaluronic acid produced by Streptococcus zooepidemicus CCT 7546. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2022, 52, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Necas, J.; Bartosikova, L.; Brauner, P.; Kolar, J.J. Hyaluronic acid (hyaluronan): A review. Vet. Med. 2018, 53, 397–411.

- Kaul, A.; Short, W.D.; Wang, X.; Keswani, S.G. Hyaluronidases in human diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Smith, M.J.; Dempsey, S.G.; Veale, R.W.; Duston-Fursman, C.G.; Rayner, C.A.; Javanapong, C.; Gerneke, D.; Dowling, S.G.; Bosque, B.A.; Karnik, T.; et al. Further structural characterization of ovine forestomach matrix and multi-layered extracellular matrix composites for soft tissue repair. J. Biomater. Appl. 2022, 36, 996–1010.

- Smith, M.J.; Dempsey, S.G.; Veale, R.W.; Duston-Fursman, C.G.; Rayner, C.A.; Javanapong, C.; Gerneke, D.; Dowling, S.G.; Bosque, B.A.; Karnik, T.; et al. Further structural characterization of ovine forestomach matrix and multi-layered extracellular matrix composites for soft tissue repair. J. Biomater. Appl. 2022, 36, 996–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Xu, Z.; Liu, G.; Huang, J.; Wu, J. Novel glucose-responsive antioxidant hybrid hydrogel for enhanced diabetic wound repair. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 7680–7689.

- Xu, Z.; Liu, G.; Huang, J.; Wu, J. Novel glucose-responsive antioxidant hybrid hydrogel for enhanced diabetic wound repair. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 7680–7689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Lierova, A.; Kasparova, J.; Filipova, A.; Cizkova, J.; Pekarova, L.; Korecka, L.; Mannova, N.; Bilkova, Z.; Sinkorova, Z. Hyaluronic acid: Known for almost a century, but still in vogue. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 838.

- Lierova, A.; Kasparova, J.; Filipova, A.; Cizkova, J.; Pekarova, L.; Korecka, L.; Mannova, N.; Bilkova, Z.; Sinkorova, Z. Hyaluronic acid: Known for almost a century, but still in vogue. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]D’Ascola, A.; Scuruchi, M.; Ruggeri, R.M.; Avenoso, A.; Mandraffino, G.; Vicchio, T.M.; Campo, S.; Campo, G.M. Hyaluronan oligosaccharides modulate inflammatory response, NIS and thyreoglobulin expression in human thyrocytes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2020, 694, 108598.

- D’Ascola, A.; Scuruchi, M.; Ruggeri, R.M.; Avenoso, A.; Mandraffino, G.; Vicchio, T.M.; Campo, S.; Campo, G.M. Hyaluronan oligosaccharides modulate inflammatory response, NIS and thyreoglobulin expression in human thyrocytes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2020, 694, 108598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Wang, N.; Liu, C.; Wang, X.; He, T.; Li, L.; Liang, X.; Wang, L.; Song, L.; Wei, Y.; Wu, Q.; et al. Hyaluronic acid oligosaccharides improve myocardial function reconstruction and angiogenesis against myocardial infarction by regulation of macrophages. Theranostics 2019, 9, 1980–1992.

- Wang, N.; Liu, C.; Wang, X.; He, T.; Li, L.; Liang, X.; Wang, L.; Song, L.; Wei, Y.; Wu, Q.; et al. Hyaluronic acid oligosaccharides improve myocardial function reconstruction and angiogenesis against myocardial infarction by regulation of macrophages. Theranostics 2019, 9, 1980–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Gupta, R.C.; Lall, R.; Srivastava, A.; Sinha, A. Hyaluronic acid: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic trajectory. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 192.

- Gupta, R.C.; Lall, R.; Srivastava, A.; Sinha, A. Hyaluronic acid: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic trajectory. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parfenova, L.V.; Galimshina, Z.R.; Gil’fanova, G.U.; Alibaeva, E.I.; Danilko, K.V.; Pashkova, T.M.; Kartashova, O.L.; Farrakhov, R.G.; Mukaeva, V.R.; Parfenov, E.V.; et al. Hyaluronic acid bisphosphonates as antifouling antimicrobial coatings for PEO-modified titanium implants. Surf. Interfaces 2022, 28, 101678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasi, A.-M.; Popa, M.I.; Butnaru, M.; Dodi, G.; Verestiuc, L. Chemical functionalization of hyaluronic acid for drug delivery applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2014, 38, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schanté, C.E.; Zuber, G.; Herlin, C.; Vandamme, T.F. Chemical modifications of hyaluronic acid for the synthesis of derivatives for a broad range of biomedical applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 85, 469–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Huang, H. Application of hyaluronic acid as carriers in drug delivery. Drug Deliv. 2018, 25, 766–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Deng, C.; Fu, Y.; Sun, X.; Gong, T.; Zhang, Z. Repeated administration of hyaluronic acid coated liposomes with improved pharmacokinetics and reduced immune response. Mol. Pharm. 2016, 13, 1800–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Bahadur, P. Modified hyaluronic acid based materials for biomedical applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 121, 556–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade del Olmo, J.; Alonso, J.M.; Martínez, V.S.; Ruiz-Rubio, L.; González, R.P.; Vilas-Vilela, J.L.; Pérez-Álvarez, L. Biocompatible hyaluronic acid-divinyl sulfone injectable hydrogels for sustained drug release with enhanced antibacterial properties against Staphylococcus aureus. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 125, 112102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liji, P.; Skariyachan, S.; Thampi, H. Cytotoxic effects of butyric acid derivatives through GPR109A receptor in colorectal carcinoma cells by in silico and in vitro methods. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1243, 130832. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, M.Y.; Wang, C.; Galarraga, J.H.; Puré, E.; Han, L.; Burdick, J.A. Influence of hyaluronic acid modification on CD44 binding towards the design of hydrogel biomaterials. Biomaterials 2019, 222, 119451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campoccia, D.; Hunt, J.A.; Doherty, P.J.; Zhong, S.P.; O’Regan, M.; Benedetti, L.; Williams, D.F. Quantitative assessment of the tissue response to films of hyaluronan derivatives. Biomaterials 1996, 17, 963–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.J.; Kielty, C.M.; Walker, M.G.; Canfield, A.E. A novel hyaluronan-based biomaterial (Hyaff-11®) as a scaffold for endothelial cells in tissue engineered vascular grafts. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 5955–5964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.-Y. Solvent composition is critical for carbodiimide cross-linking of hyaluronic acid as an ophthalmic biomaterial. Materials 2012, 5, 1986–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Sun, Y.-L.; Amadio, P.C.; Tanaka, T.; Ettema, A.M.; An, K.-N. Surface treatment of flexor tendon autografts with carbodiimide-derivatized hyaluronic acid. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2006, 88, 2181–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Este, M.; Eglin, D.; Alini, M. A systematic analysis of DMTMM vs EDC/NHS for ligation of amines to hyaluronan in water. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 108, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khunmanee, S.; Jeong, Y.; Park, H. Crosslinking method of hyaluronic-based hydrogel for biomedical applications. J. Tissue Eng. 2017, 8, 2041731417726464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thirumalaisamy, R.; Aroulmoji, V.; Iqbal, M.N.; Deepa, M.; Sivasankar, C.; Khan, R.; Selvankumar, T. Molecular insights of hyaluronic acid-hydroxychloroquine conjugate as a promising drug in targeting SARS-CoV-2 viral proteins. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1238, 130457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]