| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ZUBAIR AHMED RATAN | + 2772 word(s) | 2772 | 2021-05-14 05:06:43 | | | |

| 2 | Bruce Ren | -21 word(s) | 2751 | 2021-05-17 02:53:54 | | |

Video Upload Options

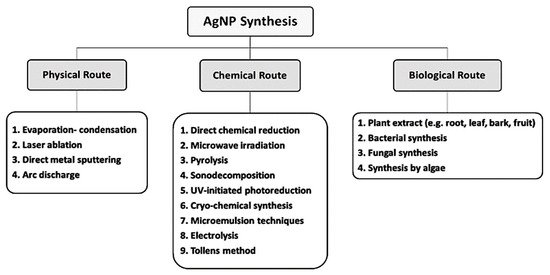

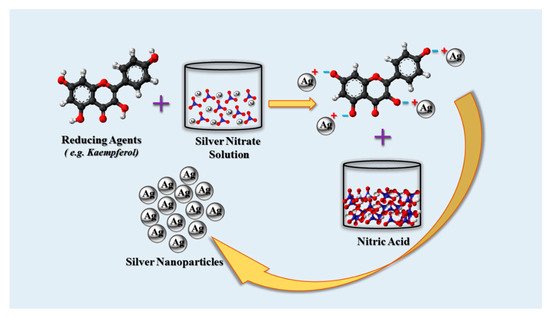

Nanobiotechnology has grown rapidly and become an integral part of modern disease diagnosis and treatment. Biosynthesized silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) are a class of eco-friendly, cost-effective and biocompatible agents that have attracted attention for their possible biomedical and bioengineering applications. Like many other inorganic and organic nanoparticles, such as AuNPs, iron oxide and quantum dots, AgNPs have also been widely studied as components of advanced anticancer agents in order to better manage cancer in the clinic. AgNPs are typically produced by the action of reducing reagents on silver ions. In addition to numerous laboratory-based methods for reduction of silver ions, living organisms and natural products can be effective and superior source for synthesis of AgNPs precursors. Currently, plants, bacteria and fungi can afford biogenic AgNPs precursors with diverse geometries and surface properties.

1. Introduction

2. Properties of AgNPs

2.1. Shape and Size

2.2. Optical Properties

2.3. Electrical Properties

3. Biologic Synthesis of AgNPs

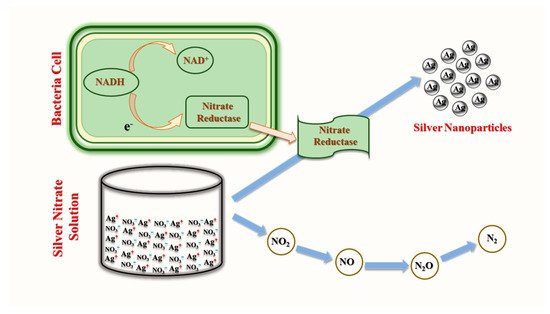

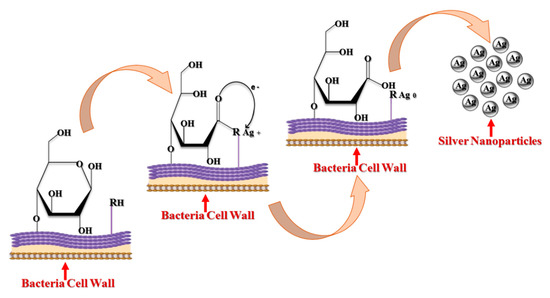

3.1. Bacterial Synthesis of AgNPs

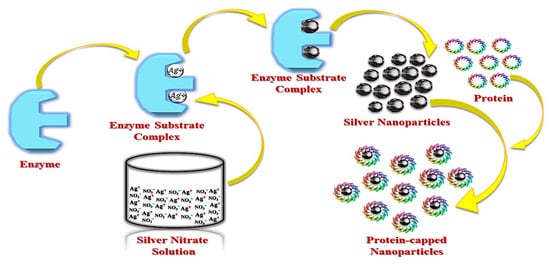

3.2. Fungal Synthesis of AgNPs

3.3. Plant Synthesis of AgNPs

| Plant | Phytochemical | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Alternanthera tenella | Flavonoids | [65] |

| Cocos nucifera | Carbohydrates, alkaloids, terpenoids, tannins, saponins, phenolics and reducing sugars | [68] |

| Lemongrass | Reducing sugars | [69] |

| Ocimum sanctum | Caffeine | [70] |

| Chrysanthemum indicum | Tannins, flavonoids and glycosides | [71] |

| Dalbergia spinose | Reducing sugars and flavonoids | [72] |

| Cinnamomum camphora | Phenolics, terpenoids, polysaccharides and flavones | [73] |

| Eucalyptus hybrid | Flavonoids and terpenoids | [74] |

References

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424.

- Vickers, A. Alternative cancer cures:“Unproven” or “disproven”? CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2004, 54, 110–118.

- Wang, M.; Thanou, M. Targeting nanoparticles to cancer. Pharmacol. Res. 2010, 62, 90–99.

- Chouhan, N. Silver nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization and applications. In Silver Nanoparticles-Fabrication, Characterization and Applications; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018; pp. 21–57.

- Nguyen, K.T. Targeted nanoparticles for cancer therapy: Promises and challenge. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. 2011.

- Li, X.; Cui, R.; Liu, W.; Sun, L.; Yu, B.; Fan, Y.; Feng, Q.; Cui, F.; Watari, F. The use of nanoscaled fibers or tubes to improve biocompatibility and bioactivity of biomedical materials. J. Nanomater. 2013, 2013.

- Russell, A.; Hugo, W. 7 antimicrobial activity and action of silver. Prog. Med. Chem. 1994, 31, 351–370.

- Lee, S.H.; Jun, B.-H. Silver nanoparticles: Synthesis and application for nanomedicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 865.

- Chen, X.; Schluesener, H.J. Nanosilver: A nanoproduct in medical application. Toxicol. Lett. 2008, 176, 1–12.

- Guilger-Casagrande, M.; de Lima, R. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles mediated by fungi: A Review. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 287.

- Ratika, K.; Vedpriya, A. Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from aqueous leaf extracts of Carica papaya and its antibacterial activity. Int. J. Nanomater. Biostructures 2013, 3, 17–20.

- Paulkumar, K.; Gnanajobitha, G.; Vanaja, M.; Rajeshkumar, S.; Malarkodi, C.; Pandian, K.; Annadurai, G. Piper nigrum leaf and stem assisted green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and evaluation of its antibacterial activity against agricultural plant pathogens. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 829894.

- Nair, B.; Pradeep, T. Coalescence of nanoclusters and formation of submicron crystallites assisted by Lactobacillus strains. Cryst. Growth Des. 2002, 2, 293–298.

- Makarov, V.; Love, A.; Sinitsyna, O.; Makarova, S.; Yaminsky, I.; Taliansky, M.; Kalinina, N. “Green” nanotechnologies: Synthesis of metal nanoparticles using plants. Acta Nat. 2014, 6, 35–44.

- Fayaz, A.M.; Balaji, K.; Kalaichelvan, P.; Venkatesan, R. Fungal based synthesis of silver nanoparticles—An effect of temperature on the size of particles. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2009, 74, 123–126.

- Dhanalakshmi, P.; Azeez, R.; Rekha, R.; Poonkodi, S.; Nallamuthu, T. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using green and brown seaweeds. Phykos 2012, 42, 39–45.

- Shiny, P.; Mukherjee, A.; Chandrasekaran, N. Marine algae mediated synthesis of the silver nanoparticles and its antibacterial efficiency. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci 2013, 5, 239–241.

- Mie, R.; Samsudin, M.W.; Din, L.B.; Ahmad, A.; Ibrahim, N.; Adnan, S.N.A. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles with antibacterial activity using the lichen Parmotrema praesorediosum. Int. J. Nanomed. 2014, 9, 121.

- Zhang, X.-F.; Liu, Z.-G.; Shen, W.; Gurunathan, S. Silver nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization, properties, applications, and therapeutic approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1534.

- Hussain, I.; Singh, N.; Singh, A.; Singh, H.; Singh, S. Green synthesis of nanoparticles and its potential application. Biotechnol. Lett. 2016, 38, 545–560.

- Yoon, K.-Y.; Byeon, J.H.; Park, J.-H.; Hwang, J. Susceptibility constants of Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis to silver and copper nanoparticles. Sci. Total Environ. 2007, 373, 572–575.

- Aziz, N.; Sherwani, A.; Faraz, M.; Fatma, T.; Prasad, R. Illuminating the anticancerous efficacy of a new fungal chassis for silver nanoparticle synthesis. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 65.

- Sukirtha, R.; Priyanka, K.M.; Antony, J.J.; Kamalakkannan, S.; Thangam, R.; Gunasekaran, P.; Krishnan, M.; Achiraman, S. Cytotoxic effect of green synthesized silver nanoparticles using Melia azedarach against in vitro HeLa cell lines and lymphoma mice model. Process Biochem. 2012, 47, 273–279.

- Boca-Farcau, S.; Potara, M.; Simon, T.; Juhem, A.; Baldeck, P.; Astilean, S. Folic acid-conjugated, SERS-labeled silver nanotriangles for multimodal detection and targeted photothermal treatment on human ovarian cancer cells. Mol. Pharm. 2014, 11, 391–399.

- Vasanth, K.; Ilango, K.; MohanKumar, R.; Agrawal, A.; Dubey, G.P. Anticancer activity of Moringa oleifera mediated silver nanoparticles on human cervical carcinoma cells by apoptosis induction. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2014, 117, 354–359.

- Kwon, T.; Woo, H.J.; Kim, Y.H.; Lee, H.J.; Park, K.H.; Park, S.; Youn, B. Optimizing hemocompatibility of surfactant-coated silver nanoparticles in human erythrocytes. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2012, 12, 6168–6175.

- Asharani, P.; Hande, M.P.; Valiyaveettil, S. Anti-proliferative activity of silver nanoparticles. BMC Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 65.

- Wiley, B.; Sun, Y.; Mayers, B.; Xia, Y. Shape-controlled synthesis of metal nanostructures: The case of silver. Chem. A Eur. J. 2005, 11, 454–463.

- Yang, Y.; Matsubara, S.; Xiong, L.; Hayakawa, T.; Nogami, M. Solvothermal synthesis of multiple shapes of silver nanoparticles and their SERS properties. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 9095–9104.

- Narayanan, K.B.; Sakthivel, N. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles by phytopathogen Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae strain BXO8. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 23, 1287–1292.

- Klaus, T.; Joerger, R.; Olsson, E.; Granqvist, C.-G. Silver-based crystalline nanoparticles, microbially fabricated. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 13611–13614.

- Ingle, A.; Gade, A.; Pierrat, S.; Sonnichsen, C.; Rai, M. Mycosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using the fungus Fusarium acuminatum and its activity against some human pathogenic bacteria. Curr. Nanosci. 2008, 4, 141–144.

- Chen, S.; Carroll, D.L. Silver nanoplates: Size control in two dimensions and formation mechanisms. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 5500–5506.

- Santhoshkumar, T.; Rahuman, A.A.; Rajakumar, G.; Marimuthu, S.; Bagavan, A.; Jayaseelan, C.; Zahir, A.A.; Elango, G.; Kamaraj, C. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Nelumbo nucifera leaf extract and its larvicidal activity against malaria and filariasis vectors. Parasitol. Res. 2011, 108, 693–702.

- Vilchis-Nestor, A.R.; Sánchez-Mendieta, V.; Camacho-López, M.A.; Gómez-Espinosa, R.M.; Camacho-López, M.A.; Arenas-Alatorre, J.A. Solventless synthesis and optical properties of Au and Ag nanoparticles using Camellia sinensis extract. Mater. Lett. 2008, 62, 3103–3105.

- Kreibig, U.; Vollmer, M. Optical Properties of Metal Clusters; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013.

- Kelly, K.L.; Coronado, E.; Zhao, L.L.; Schatz, G.C. The Optical Properties of Metal Nanoparticles: The Influence of Size, Shape, and Dielectric Environment; ACS Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2003.

- Evanoff, D.D.; Chumanov, G. Size-controlled synthesis of nanoparticles. 2. Measurement of extinction, scattering, and absorption cross sections. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 13957–13962.

- Kajani, A.A.; Zarkesh-Esfahani, S.H.; Bordbar, A.-K.; Khosropour, A.R.; Razmjou, A.; Kardi, M. Anticancer effects of silver nanoparticles encapsulated by Taxus baccata extracts. J. Mol. Liq. 2016, 223, 549–556.

- Kajani, A.A.; Bordbar, A.-K.; Esfahani, S.H.Z.; Khosropour, A.R.; Razmjou, A. Green synthesis of anisotropic silver nanoparticles with potent anticancer activity using Taxus baccata extract. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 61394–61403.

- Lin, L.; Qiu, P.; Cao, X.; Jin, L. Colloidal silver nanoparticles modified electrode and its application to the electroanalysis of Cytochrome c. Electrochim. Acta 2008, 53, 5368–5372.

- Sankar, R.; Karthik, A.; Prabu, A.; Karthik, S.; Shivashangari, K.S.; Ravikumar, V. Origanum vulgare mediated biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles for its antibacterial and anticancer activity. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2013, 108, 80–84.

- Sepeur, S. Nanotechnology: Technical Basics and Applications; Vincentz Network GmbH & Co KG: Hanover, Germany, 2008.

- Meyers, M.A.; Mishra, A.; Benson, D.J. Mechanical properties of nanocrystalline materials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2006, 51, 427–556.

- Thakkar, K.N.; Mhatre, S.S.; Parikh, R.Y. Biological synthesis of metallic nanoparticles. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2010, 6, 257–262.

- Mukherjee, P.; Ahmad, A.; Mandal, D.; Senapati, S.; Sainkar, S.R.; Khan, M.I.; Parishcha, R.; Ajaykumar, P.; Alam, M.; Kumar, R. Fungus-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their immobilization in the mycelial matrix: A novel biological approach to nanoparticle synthesis. Nano Lett. 2001, 1, 515–519.

- Mittal, A.K.; Chisti, Y.; Banerjee, U.C. Synthesis of metallic nanoparticles using plant extracts. Biotechnol. Adv. 2013, 31, 346–356.

- Kalishwaralal, K.; Deepak, V.; Ramkumarpandian, S.; Nellaiah, H.; Sangiliyandi, G. Extracellular biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles by the culture supernatant of Bacillus licheniformis. Mater. Lett. 2008, 62, 4411–4413.

- Sintubin, L.; Verstraete, W.; Boon, N. Biologically produced nanosilver: Current state and future perspectives. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2012, 109, 2422–2436.

- Prabhu, S.; Poulose, E.K. Silver nanoparticles: Mechanism of antimicrobial action, synthesis, medical applications, and toxicity effects. Int. Nano Lett. 2012, 2, 32.

- Karthik, L.; Kumar, G.; Kirthi, A.V.; Rahuman, A.; Rao, K.B. Streptomyces sp. LK3 mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and its biomedical application. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2014, 37, 261–267.

- Vaidyanathan, R.; Gopalram, S.; Kalishwaralal, K.; Deepak, V.; Pandian, S.R.K.; Gurunathan, S. Enhanced silver nanoparticle synthesis by optimization of nitrate reductase activity. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2010, 75, 335–341.

- Kalimuthu, K.; Babu, R.S.; Venkataraman, D.; Bilal, M.; Gurunathan, S. Biosynthesis of silver nanocrystals by Bacillus licheniformis. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2008, 65, 150–153.

- Golinska, P.; Wypij, M.; Ingle, A.P.; Gupta, I.; Dahm, H.; Rai, M. Biogenic synthesis of metal nanoparticles from actinomycetes: Biomedical applications and cytotoxicity. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 8083–8097.

- Van Hullebusch, E.D.; Zandvoort, M.H.; Lens, P.N. Metal immobilisation by biofilms: Mechanisms and analytical tools. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2003, 2, 9–33.

- Lin, Z.; Zhou, C.; Wu, J.; Zhou, J.; Wang, L. A further insight into the mechanism of Ag+ biosorption by Lactobacillus sp. strain A09. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2005, 61, 1195–1200.

- Sintubin, L.; De Windt, W.; Dick, J.; Mast, J.; van der Ha, D.; Verstraete, W.; Boon, N. Lactic acid bacteria as reducing and capping agent for the fast and efficient production of silver nanoparticles. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 84, 741–749.

- Mohanpuria, P.; Rana, N.K.; Yadav, S.K. Biosynthesis of nanoparticles: Technological concepts and future applications. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2008, 10, 507–517.

- Dhillon, G.S.; Brar, S.K.; Kaur, S.; Verma, M. Green approach for nanoparticle biosynthesis by fungi: Current trends and applications. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2012, 32, 49–73.

- Jain, N.; Bhargava, A.; Majumdar, S.; Tarafdar, J.; Panwar, J. Extracellular biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Aspergillus flavus NJP08: A mechanism perspective. Nanoscale 2011, 3, 635–641.

- Kuppusamy, P.; Ichwan, S.J.; Al-Zikri, P.N.H.; Suriyah, W.H.; Soundharrajan, I.; Govindan, N.; Maniam, G.P.; Yusoff, M.M. In vitro anticancer activity of Au, Ag nanoparticles synthesized using Commelina nudiflora L. aqueous extract against HCT-116 colon cancer cells. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2016, 173, 297–305.

- Ramasamy, M.; Lee, J.-H.; Lee, J. Direct one-pot synthesis of cinnamaldehyde immobilized on gold nanoparticles and their antibiofilm properties. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2017, 160, 639–648.

- Kumar, V.; Yadav, S.K. Plant-mediated synthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles and their applications. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2009, 84, 151–157.

- Mukunthan, K.; Balaji, S. Cashew apple juice (Anacardium occidentale L.) speeds up the synthesis of silver nanoparticles. Int. J. Green Nanotechnol. 2012, 4, 71–79.

- Sathishkumar, P.; Vennila, K.; Jayakumar, R.; Yusoff, A.R.M.; Hadibarata, T.; Palvannan, T. Phyto-synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Alternanthera tenella leaf extract: An effective inhibitor for the migration of human breast adenocarcinoma (MCF-7) cells. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2016, 39, 651–659.

- Vijayaraghavan, K.; Nalini, S.K.; Prakash, N.U.; Madhankumar, D. Biomimetic synthesis of silver nanoparticles by aqueous extract of Syzygium aromaticum. Mater. Lett. 2012, 75, 33–35.

- Jasuja, N.D.; Gupta, D.K.; Reza, M.; Joshi, S.C. Green Synthesis of AgNPs Stabilized with biowaste and their antimicrobial activities. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2014, 45, 1325–1332.

- Mariselvam, R.; Ranjitsingh, A.; Nanthini, A.U.R.; Kalirajan, K.; Padmalatha, C.; Selvakumar, P.M. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from the extract of the inflorescence of Cocos nucifera (Family: Arecaceae) for enhanced antibacterial activity. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2014, 129, 537–541.

- Shankar, S.S.; Rai, A.; Ahmad, A.; Sastry, M. Controlling the optical properties of lemongrass extract synthesized gold nanotriangles and potential application in infrared-absorbing optical coatings. Chem. Mater. 2005, 17, 566–572.

- Ramteke, C.; Chakrabarti, T.; Sarangi, B.K.; Pandey, R.-A. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles from the aqueous extract of leaves of Ocimum sanctum for enhanced antibacterial activity. J. Chem. 2012, 2013, 278925.

- Arokiyaraj, S.; Arasu, M.V.; Vincent, S.; Prakash, N.U.; Choi, S.H.; Oh, Y.-K.; Choi, K.C.; Kim, K.H. Rapid green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Chrysanthemum indicum L and its antibacterial and cytotoxic effects: An in vitro study. Int. J. Nanomed. 2014, 9, 379.

- Muniyappan, N.; Nagarajan, N. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles with Dalbergia spinosa leaves and their applications in biological and catalytic activities. Process Biochem. 2014, 49, 1054–1061.

- Vijayaraghavan, K.; Nalini, S.K.; Prakash, N.U.; Madhankumar, D. One step green synthesis of silver nano/microparticles using extracts of Trachyspermum ammi and Papaver somniferum. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2012, 94, 114–117.

- Dubey, M.; Bhadauria, S.; Kushwah, B. Green synthesis of nanosilver particles from extract of Eucalyptus hybrida (safeda) leaf. Dig. J. Nanomater. Biostructures 2009, 4, 537–543.