| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mariela Luján Tomazic | -- | 5226 | 2023-06-16 21:07:22 | | | |

| 2 | Mariela Luján Tomazic | + 2 word(s) | 5228 | 2023-06-17 02:40:58 | | | | |

| 3 | Fanny Huang | Meta information modification | 5228 | 2023-06-19 08:16:36 | | |

Video Upload Options

Poultry is the first source of animal protein for human consumption. Chicken coccidiosis is a highly widespread enteric disease caused by Eimeria spp. which causes significant economic losses to the poultry industry worldwide; however, the impact on family poultry holders or backyard production—which plays a key role in food security and involves mainly rural women—has been little explored. Coccidiosis disease is controlled by good husbandry measures, chemoprophylaxis, and/or live vaccination. Current limitations on the use of live vaccines have led to research in next-generation vaccines based on recombinant or live-vectored vaccines. Next-generation vaccines are required to control this complex parasitic disease, and for this purpose, protective antigens need to be identified.

1. Introduction

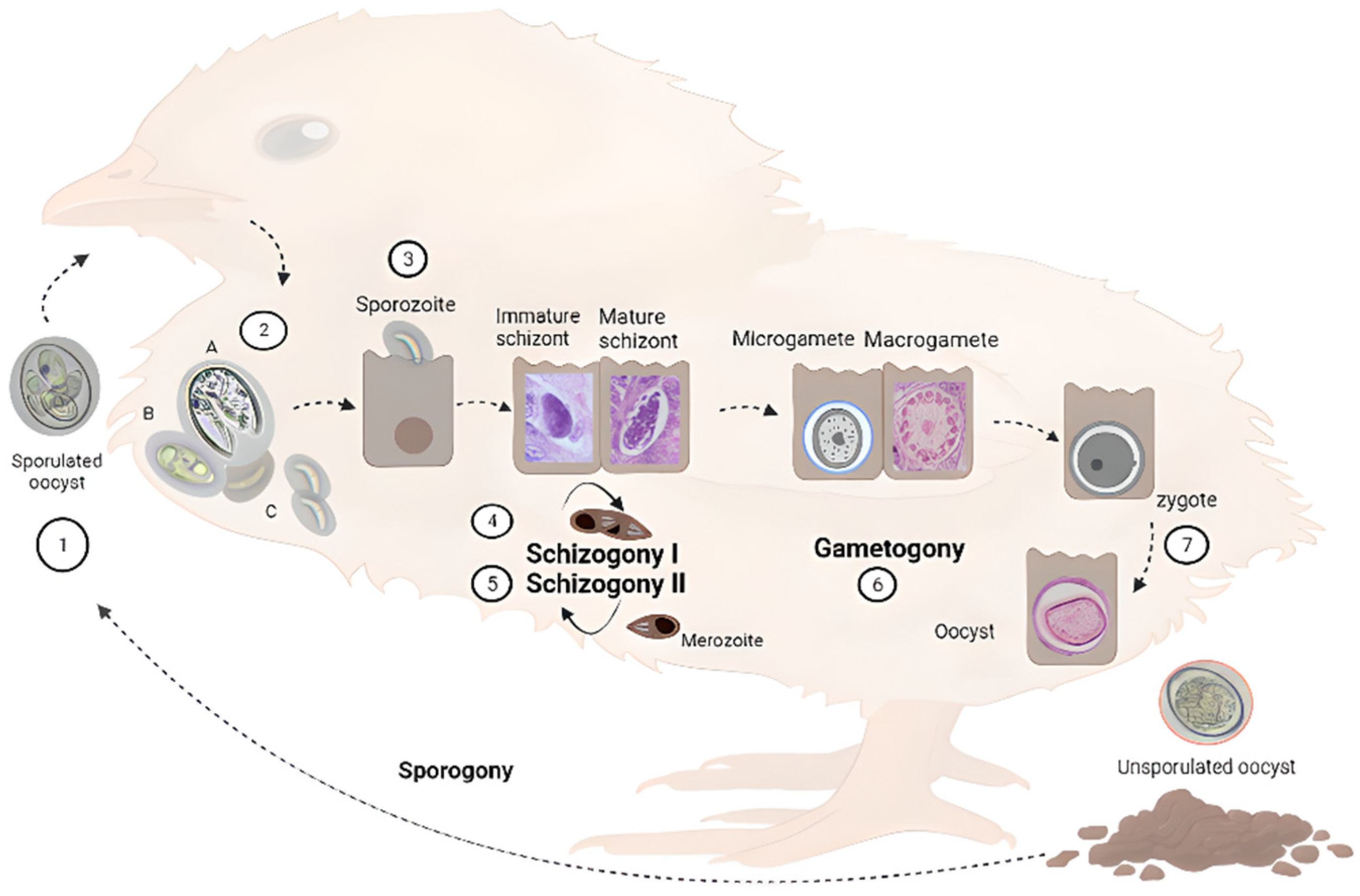

2. Life Cycle of Eimeria spp.

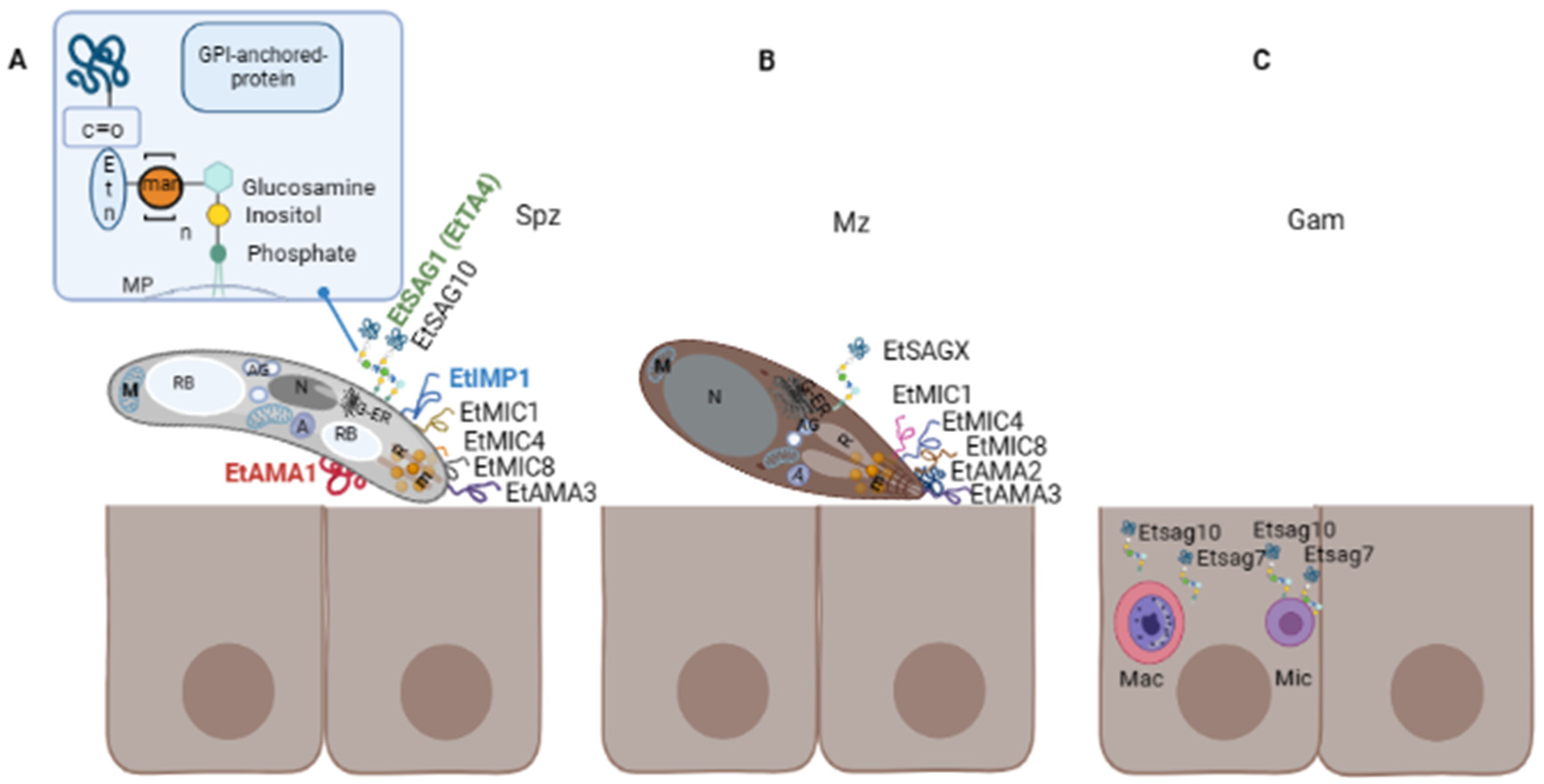

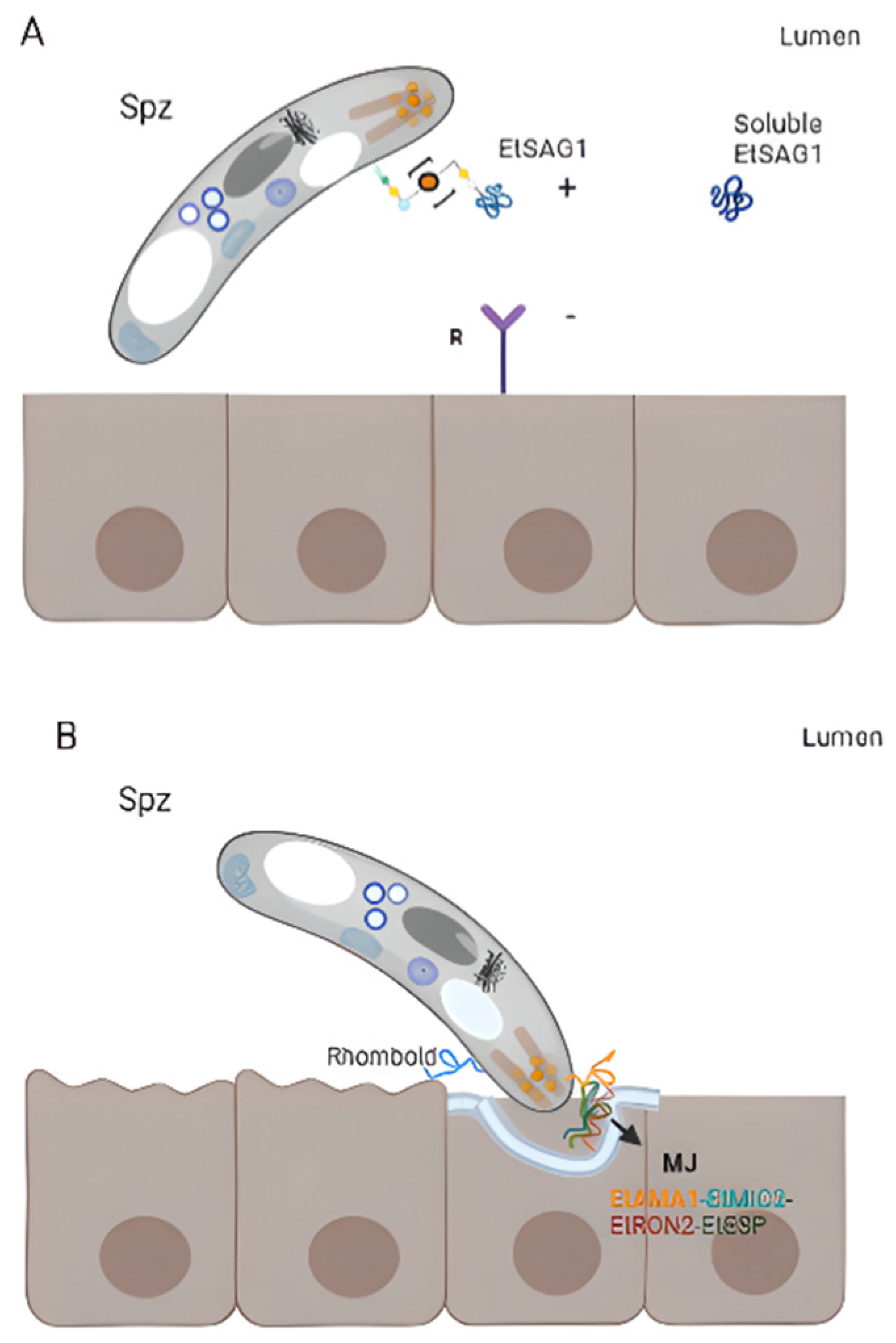

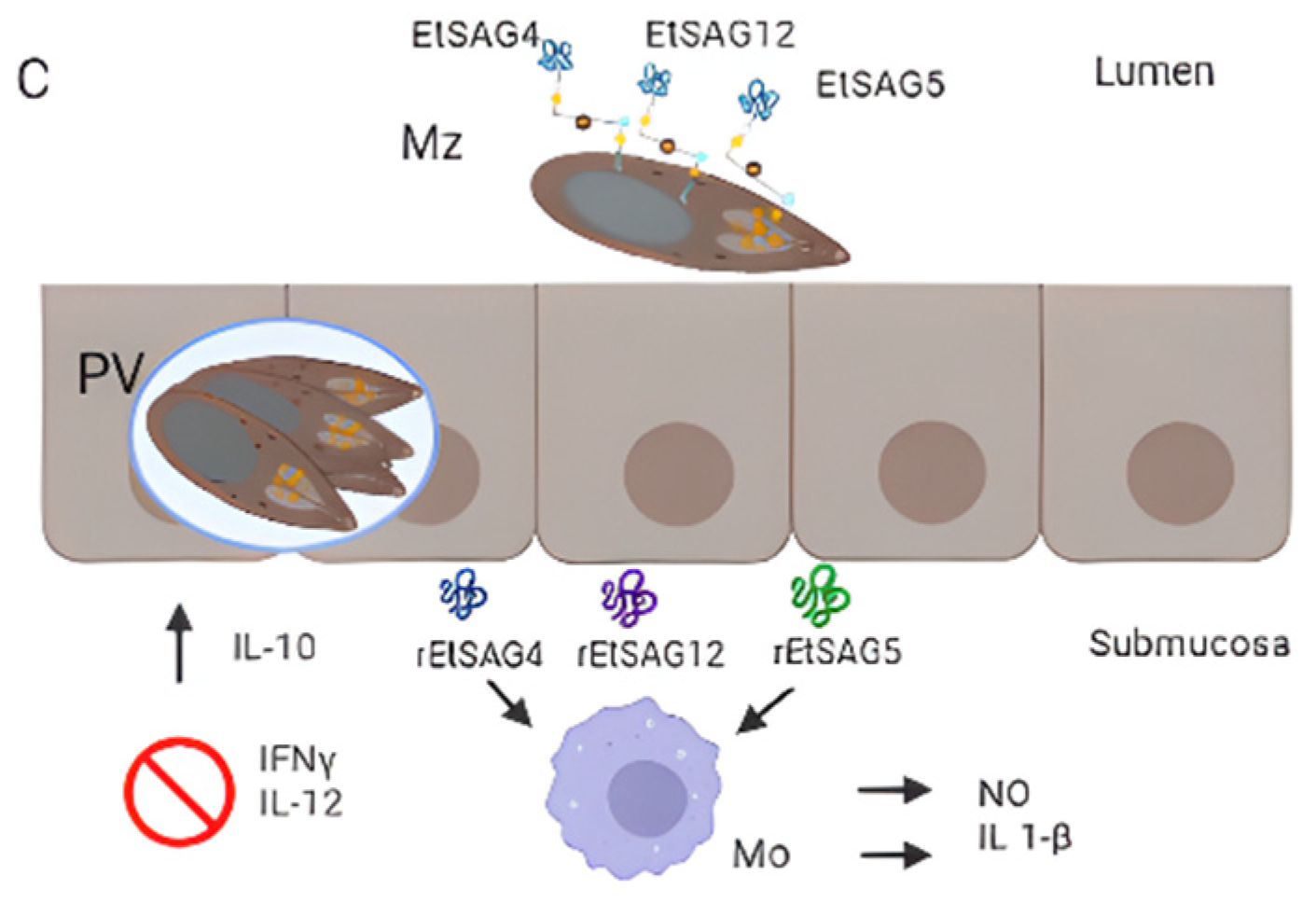

3. Surface Proteins of Eimeria spp.

3.1. Eimeria acervulina

3.2. Eimeria brunetti

3.3. Eimeria maxima

3.4. Eimeria mitis

3.5. Eimeria necatrix

3.6. Eimeria tenella

References

- Adl, S.M.; Simpson, A.G.B.; Lane, C.E.; Lukeš, J.; Bass, D.; Bowser, S.S.; Brown, M.W.; Burki, F.; Dunthorn, M.; Hampl, V.; et al. The Revised Classification of Eukaryotes. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2012, 59, 429–514.

- Blake, D.P.; Worthing, K.; Jenkins, M.C. Exploring Eimeria Genomes to Understand Population Biology: Recent Progress and Future Opportunities. Genes 2020, 11, 1103.

- FAO. Understanding and Integrating Gender Issues in Livestock Proyects and Programmes; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2013.

- Portillo Salgado, R.; Vazquez Martinez, I. Género y Seguridad Alimentaria: Rol e Importancia de La Mujer En La Avicultura de Traspatio En Tetela de Ocampo, Puebla, México. Temas Cienc. Tecnol. 2019, 23, 33–40.

- Ahmed, S.; Begum, M.; Khatun, A.; Gofur, M.R.; Azad, M.T.; Kabir, A.; Haque, T.S. Family Poultry (FP) as a Tool for Improving Gender Equity and Women’s Empowerment in Developing Countries: Evidence from Bangladesh. Eur. J. Agric. Food Sci. 2021, 3, 37–44.

- Kumar, M.; Dahiya, S.P.; Ratwan, P. Backyard Poultry Farming in India: A Tool for Nutritional Security and Women Empowerment. Biol. Rhythm. Res. 2021, 52, 1476–1491.

- Di Pillo, F.; Anríquez, G.; Alarcón, P.; Jimenez-Bluhm, P.; Galdames, P.; Nieto, V.; Schultz-Cherry, S.; Hamilton-West, C. Backyard Poultry Production in Chile: Animal Health Management and Contribution to Food Access in an Upper Middle-Income Country. Prev. Vet. Med. 2019, 164, 41–48.

- Ashenafi, H.; Tadesse, S.; Medhin, G.; Tibbo, M. Study on Coccidiosis of Scavenging Indigenous Chickens in Central Ethiopia. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2004, 36, 693–701.

- Khursheed, A.; Yadav, A.; Sofi, O.M.U.D.; Kushwaha, A.; Yadav, V.; Rafiqi, S.I.; Godara, R.; Katoch, R. Prevalence and Molecular Characterization of Eimeria Species Affecting Backyard Poultry of Jammu Region, North India. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2022, 54, 296.

- Lawal, J.R.; Jajere, S.M.; Ibrahim, U.I.; Geidam, Y.A.; Gulani, I.A.; Musa, G.; Ibekwe, B.U. Prevalence of Coccidiosis among Village and Exotic Breed of Chickens in Maiduguri, Nigeria. Vet. World 2016, 9, 653–659.

- Sharma, S.; Iqbal, A.; Azmi, S.; Mushtaq, I.; Wani, Z.A.; Ahmad, S. Prevalence of Poultry Coccidiosis in Jammu Region of Jammu & Kashmir State. J. Parasit. Dis. 2015, 39, 85–89.

- Andreopoulou, M.; Chaligiannis, I.; Sotiraki, S.; Daugschies, A.; Bangoura, B. Prevalence and Molecular Detection of Eimeria Species in Different Types of Poultry in Greece and Associated Risk Factors. Parasitol. Res. 2022, 121, 2051–2063.

- Godwin, R.M.; Morgan, J.A.T. A Molecular Survey of Eimeria in Chickens across Australia. Vet. Parasitol. 2015, 214, 16–21.

- Rochell, S.J.; Parsons, C.M.; Dilger, R.N. Effects of Eimeria acervulina Infection Severity on Growth Performance, Apparent Ileal Amino Acid Digestibility, and Plasma Concentrations of Amino Acids, Carotenoids, and A1-Acid Glycoprotein in Broilers. Poult. Sci. 2016, 95, 1573–1581.

- Dalibard, P.; Hess, V.; Tutour, L.; Peisker, M.; Peris, S.; Gutierrez, A.P.; Redshaw, M. (Eds.) Amino Acid in Animal Nutrition; EU Feed Additives and Premixtures Association (FEFANA): Brussels, Belgium, 2014; ISBN 9782960128932.

- Mesa-Pineda, C.; Navarro-Ruíz, J.L.; López-Osorio, S.; Chaparro-Gutiérrez, J.J.; Gómez-Osorio, L.M. Chicken Coccidiosis: From the Parasite Lifecycle to Control of the Disease. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 787653.

- Hauck, R.; Carrisosa, M.; Mccrea, B.A.; Dormitorio, T.; Macklin, K.S. Evaluation of Next-Generation Amplicon Sequencing to Identify Eimeria spp. of Chickens. Avian Dis. 2019, 63, 577–583.

- Hinsu, A.T.; Thakkar, J.R.; Koringa, P.G.; Vrba, V.; Jakhesara, S.J.; Psifidi, A.; Guitian, J.; Tomley, F.M.; Rank, D.N.; Raman, M.; et al. Illumina Next Generation Sequencing for the Analysis of Eimeria Populations in Commercial Broilers and Indigenous Chickens. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 176.

- Venkatas, J.; Adeleke, M.A. Emerging Threat of Eimeria Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) on Poultry Production. Parasitology 2019, 146, 1615–1619.

- Blake, D.P.; Vrba, V.; Xia, D.; Jatau, I.D.; Spiro, S.; Nolan, M.J.; Underwood, G.; Tomley, F.M. Genetic and Biological Characterisation of Three Cryptic Eimeria Operational Taxonomic Units That Infect Chickens (Gallus gallus domesticus). Int. J. Parasitol. 2021, 51, 621–634.

- Ojimelukwe, A.E.; Emedhem, D.E.; Agu, G.O.; Nduka, F.O.; Abah, A.E. Populations of Eimeria tenella Express Resistance to Commonly Used Anticoccidial Drugs in Southern Nigeria. Int. J. Vet. Sci. Med. 2018, 6, 192–200.

- Tan, L.; Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Ke, Q.; Lei, W.; Mughal, M.N.; Fang, R.; Zhou, Y.; Shen, B.; Zhao, J. Genetic Diversity and Drug Sensitivity Studies on Eimeria tenella Field Isolates from Hubei Province of China. Parasit. Vectors 2017, 10, 137.

- Xie, Y.; Huang, B.; Xu, L.; Zhao, Q.; Zhu, S.; Zhao, H.; Dong, H.; Han, H. Comparative Transcriptome Analyses of Drug-Sensitive and Drug-Resistant Strains of Eimeria tenella by RNA-Sequencing. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2020, 67, 406–416.

- Norton, C.C.; Joyner, L.P. The Development of Drug-Resistant Strains of Eimeria maxima in the Laboratory. Parasitology 1975, 71, 153–165.

- Blake, D.P. Eimeria Genomics: Where Are We Now and Where Are We Going? Vet. Parasitol. 2015, 212, 68–74.

- Soutter, F.; Werling, D.; Tomley, F.M.; Blake, D.P. Poultry Coccidiosis: Design and Interpretation of Vaccine Studies. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 101.

- Williams, R.B. Historical Article: Fifty Years of Anticoccidial Vaccines for Poultry (1952–2002). Avian Dis. 2002, 46, 775–802.

- Wallach, M.G.; Ashash, U.; Michael, A.; Smith, N.C. Field Application of a Subunit Vaccine against an Enteric Protozoan Disease. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3948.

- Gumina, E.; Hall, J.W.; Vecchi, B.; Hernandez-Velasco, X.; Lumpkins, B.; Mathis, G.; Layton, S. Evaluation of a Subunit Vaccine Candidate (Biotech Vac Cox) against Eimeria spp. in Broiler Chickens. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101329.

- Tomazic, M.L.; Marugan-Hernandez, V.; Rodriguez, A.E. Next-Generation Technologies and Systems Biology for the Design of Novel Vaccines Against Apicomplexan Parasites. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 8, 800361.

- Heitlinger, E.; Spork, S.; Lucius, R.; Dieterich, C. The Genome of Eimeria falciformis—Reduction and Specialization in a Single Host Apicomplexan Parasite. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 696.

- Reid, A.J.; Blake, D.P.; Ansari, H.R.; Billington, K.; Browne, H.P.; Bryant, J.; Dunn, M.; Hung, S.S.; Kawahara, F.; Miranda-Saavedra, D.; et al. Genomic Analysis of the Causative Agents of Coccidiosis in Domestic Chickens. Genome Res. 2014, 24, 1676–1685.

- Mcdonald, V.; Shirley, M.W.; Millard, B.J. A Comparative Study of Two Lines of Eimeria tenella Attenuated Either by Selection for Precocious Development in the Chicken or by Growth in Chicken Embryos. Avian Pathol. 1986, 15, 323–335.

- McDonald, V.; Wisher, M.H.; Rose, M.E.; Jeffers, T.K. Eimeria tenella: Immunological Diversity between Asexual Generations. Parasite Immunol. 1988, 10, 649–660.

- Belli, S.I.; Ferguson, D.J.P.; Katrib, M.; Slapetova, I.; Mai, K.; Slapeta, J.; Flowers, S.A.; Miska, K.B.; Tomley, F.M.; Shirley, M.W.; et al. Conservation of Proteins Involved in Oocyst Wall Formation in Eimeria maxima, Eimeria tenella and Eimeria acervulina. Int. J. Parasitol. 2009, 39, 1063–1070.

- López-Osorio, S.; Chaparro-Gutiérrez, J.J.; Gómez-Osorio, L.M. Overview of Poultry Eimeria Life Cycle and Host-Parasite Interactions. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 384.

- Burrell, A.; Tomley, F.M.; Vaughan, S.; Marugan-Hernandez, V. Life Cycle Stages, Specific Organelles and Invasion Mechanisms of Eimeria Species. Parasitology 2020, 147, 263–278.

- Tyler, J.S.; Boothroyd, J.C. The C-Terminus of Toxoplasma RON2 Provides the Crucial Link between AMA1 and the Host-Associated Invasion Complex. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1001282.

- Bangoura, B.; Daugschies, A. Eimeria. In Parasitic Protozoa of Farm Animals and Pets; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 55–92. ISBN 9783319701325.

- Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Zheng, H.; Xu, Z.; Roellig, D.M.; Li, N.; Frace, M.A.; Tang, K.; Arrowood, M.J.; Moss, D.M.; et al. Comparative Genomics Reveals Cyclospora cayetanensis Possesses Coccidia-like Metabolism and Invasion Components but Unique Surface Antigens. BMC Genom. 2016, 17, 316.

- Tachado, S.D.; Mazhari-Tabrizi, R.; Schofield, L. Specificity in Signal Transduction among Glycosylphosphatidylinositols of Plasmodium falciparum, Trypanosoma brucei, Trypanosoma cruzi and Leishmania spp. Parasite Immunol. 1999, 21, 609–617.

- Gowda, D.C. TLR-Mediated Cell Signaling by Malaria GPIs. Trends Parasitol. 2007, 23, 596–604.

- Debierre-Grockiego, F.; Campos, M.A.; Azzouz, N.; Schmidt, J.; Bieker, U.; Resende, M.G.; Mansur, D.S.; Weingart, R.; Schmidt, R.R.; Golenbock, D.T.; et al. Activation of TLR2 and TLR4 by Glycosylphosphatidylinositols Derived from Toxoplasma gondii. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 1129–1137.

- Delbecq, S. Major Surface Antigens in Zoonotic Babesia. Pathogens 2022, 11, 99.

- Tabarés, E.; Ferguson, D.; Clark, J.; Soon, P.E.; Wan, K.L.; Tomley, F. Eimeria tenella Sporozoites and Merozoites Differentially Express Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-Anchored Variant Surface Proteins. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2004, 135, 123–132.

- Jahn, D.; Matros, A.; Bakulina, A.Y.; Tiedemann, J.; Schubert, U.; Giersberg, M.; Haehnel, S.; Zoufal, K.; Mock, H.P.; Kipriyanov, S.M. Model Structure of the Immunodominant Surface Antigen of Eimeria tenella Identified as a Target for Sporozoite-Neutralizing Monoclonal Antibody. Parasitol. Res. 2009, 105, 655–668.

- Liu, G.; Zhu, S.; Zhao, Q.; Dong, H.; Huang, B.; Zhao, H.; Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Han, H. Molecular Characterization of Surface Antigen 10 of Eimeria tenella. Parasitol. Res. 2019, 118, 2989–2999.

- Carruthers, V.B.; Tomley, F.M. Microneme Proteins in Apicomplexans. Subcell. Biochem. 2008, 47, 33–45.

- Lovett, J.L.; Marchesini, N.; Moreno, S.N.J.; Sibley, L.D. Toxoplasma gondii Microneme Secretion Involves Intracellular Ca2+ Release from Inositol 1,4,5-Triphosphate (IP3)/Ryanodine-Sensitive Stores. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 25870–25876.

- Donahue, C.; Carruthers, V.B.; Gilk, S.D.; Ward, G.E. The Toxoplasma Homolog of Plasmodium Apical Membrane Antigen-1 (AMA-1) Is a Microneme Protein Secreted in Response to Elevated Intracellular Calcium Levels. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2000, 111, 15–30.

- Tomley, F.M.; Bumstead, J.M.; Billington, K.J.; Dunn, P.P. Molecular Cloning and Characterization of a Novel Acidic Microneme Protein (Etmic-2) from the Apicomplexan Protozoan Parasite, Eimeria tenella. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1996, 79, 195–206.

- Tomley, F.M.; Billington, K.J.; Bumstead, J.M.; Clark, J.D.; Monaghan, P. EtMIC4: A Microneme Protein from Eimeria tenella That Contains Tandem Arrays of Epidermal Growth Factor-like Repeats and Thrombospondin Type-I Repeats. Int. J. Parasitol. 2001, 31, 1303–1310.

- Gras, S.; Jackson, A.; Woods, S.; Pall, G.; Whitelaw, J.; Leung, J.M.; Ward, G.E.; Roberts, C.W.; Meissner, M. Parasites Lacking the Micronemal Protein MIC2 Are Deficient in Surface Attachment and Host Cell Egress, but Remain Virulent in Vivo. Wellcome Open Res. 2017, 2, 32.

- Marugan-Hernandez, V.; Fiddy, R.; Nurse-Francis, J.; Smith, O.; Pritchard, L.; Tomley, F.M. Characterization of Novel Microneme Adhesive Repeats (MAR) in Eimeria tenella. Parasit. Vectors 2017, 10, 491.

- Periz, J.; Gill, A.C.; Hunt, L.; Brown, P.; Tomley, F.M. The Microneme Proteins EtMIC4 and EtMIC5 of Eimeria tenella Form a Novel, Ultra-High Molecular Mass Protein Complex That Binds Target Host Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 16891–16898.

- Zhao, N.; Ming, S.; Sun, L.; Wang, B.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, X. Identification and Characterization of Eimeria tenella Microneme Protein (EtMIC8). Microbiol. Spectr. 2021, 9, e0022821.

- Deans, J.A.; Alderson, T.; Thomas, A.W.; Mitchell, G.H.; Lennox, E.S.; Cohen, S. Rat Monoclonal Antibodies Which Inhibit the in Vitro Multiplication of Plasmodium knowlesi. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1982, 49, 297–309.

- Macraild, C.A.; Anders, R.F.; Foley, M.; Norton, R.S. Apical Membrane Antigen. 1 as an Anti-Malarial Drug. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2011, 11, 2039–2047.

- Gaffar, F.R.; Yatsuda, A.P.; Franssen, F.F.J.; de Vries, E. Erythrocyte Invasion by Babesia bovis Merozoites Is Inhibited by Polyclonal Antisera Directed against Peptides Derived from a Homologue of Plasmodium falciparum Apical Membrane Antigen 1. Infect. Immun. 2004, 72, 2947–2955.

- Triglia, T.; Healer, J.; Caruana, S.R.; Hodder, A.N.; Anders, R.F.; Crabb, B.S.; Cowman, A.F. Apical Membrane Antigen 1 Plays a Central Role in Erythrocyte Invasion by Plasmodium Species. Mol. Microbiol. 2000, 38, 706–718.

- Tonkin, M.L.; Crawford, J.; Lebrun, M.L.; Boulanger, M.J. Babesia divergens and Neospora caninum Apical Membrane Antigen 1 Structures Reveal Selectivity and Plasticity in Apicomplexan Parasite Host Cell Invasion. Protein Sci. 2013, 22, 114–127.

- Blake, D.P.; Billington, K.J.; Copestake, S.L.; Oakes, R.D.; Quail, M.A.; Wan, K.L.; Shirley, M.W.; Smith, A.L. Genetic Mapping Identifies Novel Highly Protective Antigens for an Apicomplexan Parasite. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1001279.

- Yin, G.; Lin, Q.; Wei, W.; Qin, M.; Liu, X.; Suo, X.; Huang, Z. Protective Immunity against Eimeria tenella Infection in Chickens Induced by Immunisation with a Recombinant C-Terminal Derivative of EtIMP1. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2014, 162, 117–121.

- Cui, X.; Lei, T.; Yang, D.; Hao, P.; Li, B.; Liu, Q. Toxoplasma gondii Immune Mapped Protein-1 (TgIMP1) Is a Novel Vaccine Candidate against Toxoplasmosis. Vaccine 2012, 30, 2282–2287.

- Cui, X.; Lei, T.; Yang, D.Y.; Hao, P.; Liu, Q. Identification and Characterization of a Novel Neospora caninum Immune Mapped Protein 1. Parasitology 2012, 139, 998–1004.

- Olajide, J.S.; Qu, Z.; Yang, S.; Oyelade, O.J.; Cai, J. Eimeria Proteins: Order amidst Disorder. Parasit. Vectors 2022, 15, 38.

- Jenkins, M.C.; Danforth, H.D.; Lillehoj, H.S.; Fetterer, R.H. CDNA Encoding an Immunogenic Region of a 22 Kilodalton Surface Protein of Eimeria acervulina Sporozoites. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1989, 32, 153–161.

- Jenkins, M.; Lillehoj, H.S.; Dame, A.B.; Jenkins, M.C. Eimeria acervulina: DNA Cloning and Characterization of Recombinant Sporozoite and Merozoite Antigens. Exp. Parasitol. 1988, 66, 96–107.

- Laurent, F.; Bourdieu, C.; Kazanji, M.; Yvore, P.; Pery, P. The Immunodominant Eimer acervulina Sporozoite Antigen Previously Described as P160/P240 Is a 19-Kilodalton Antigen Present in Several Eimeria Species. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1994, 63, 79–86.

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, C.; Lu, Y.; Amer, S.; Xu, P.; Wang, J.; Lu, J.; Bao, Y.; Deng, B.; He, H.; et al. Prokaryotic Expression and Identification of 3-1E Gene of Merozoite Surface Antigen of Eimeria acervulina. Parasitol. Res. 2011, 109, 1361–1365.

- Lillehoj, H.S.; Choi, K.D.; Jenkins, M.C.; Vakharia, V.N.; Song, K.D.; Han, J.Y.; Lillehoj, E.P. A Recombinant Eimeria Protein Inducing Interferon-Gamma Production: Comparison of Different Gene Expression Systems and Immunisation Strategies for Vaccination against Coccidiosis. Avian Dis. 2000, 44, 379–389.

- Ma, D.; Ma, C.; Gao, M.; Li, G.; Niu, Z.; Huang, X. Induction of Cellular Immune Response by DNA Vaccine Coexpressing, E. acervulina 3-1E Gene and Mature CHIl-15 Gene. J. Parasitol. Res. 2012, 2012, 654279.

- Yuelan, Z.; Yiwei, L.; Liyuan, L.; Yue, Z.; Wenbo, C.; Yongzhan, B.; Jianhua, Q. Expression and Identification of the ADF-Linker-3-1E Gene of Eimeria acervulina of Chicken. Parasitol. Res. 2016, 115, 1641–1647.

- Wang, P.; Jia, Y.; Han, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, J.; Guan, C.; Ying, J.; Deng, S.; Wang, J.; et al. Eimeria acervulina Microneme Protein 3 Inhibits Apoptosis of the Chicken Duodenal Epithelial Cell by Targeting the Casitas B-Lineage Lymphoma Protein. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 636809.

- Zhang, Z.C.; Huang, J.W.; Li, M.H.; Sui, Y.X.; Wang, S.; Liu, L.R.; Xu, L.X.; Yan, R.F.; Song, X.K.; Li, X.R. Identification and Molecular Characterization of Microneme 5 of Eimeria acervulina. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e115411.

- Zhang, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Huang, J.; Sun, X.; Haseeb, M.; Ahmed, S.; Shah, M.A.A.; Yan, R.; Song, X.; Xu, L.; et al. Molecular Characterization of a Potential Receptor of Eimeria acervulina Microneme Protein 3 from Chicken Duodenal Epithelial Cells. Parasite 2020, 27, 18.

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, L.; Huang, J.; Wang, S.; Lu, M.; Song, X.; Xu, L.; Yan, R.; Li, X. The Molecular Characterization and Immune Protection of Microneme 2 of Eimeria acervulina. Vet. Parasitol. 2016, 215, 96–105.

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, S.; Huang, J.; Liu, L.; Lu, M.; Li, M.; Sui, Y.; Xu, L.; Yan, R.; Song, X.; et al. Proteomic Analysis of Eimeria acervulina Sporozoite Proteins Interaction with Duodenal Epithelial Cells by Shotgun LC–MS/MS. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2015, 202, 29–33.

- Hoan, T.D.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, J.; Yan, R.; Song, X.; Xu, L.; Li, X. Identification and Immunogenicity of Microneme Protein 2 (EbMIC2) of Eimeria brunetti. Exp. Parasitol. 2016, 162, 7–17.

- Hoan, T.D.; Thao, D.T.; Gadahi, J.A.; Song, X.; Xu, L.; Yan, R.; Li, X. Analysis of Humoral Immune Response and Cytokines in Chickens Vaccinated with Eimeria brunetti Apical Membrane Antigen-1 (EbAMA1) DNA Vaccine. Exp. Parasitol. 2014, 144, 65–72.

- Yang, X.C.; Li, M.H.; Liu, J.H.; Ji, Y.H.; Li, X.R.; Xu, L.X.; Yan, R.F.; Song, X.K. Identification of Immune Protective Genes of Eimeria maxima through CDNA Expression Library Screening. Parasit. Vectors 2017, 10, 85.

- Liu, T.; Huang, J.; Li, Y.; Ehsan, M.; Wang, S.; Zhou, Z.; Song, X.; Yan, R.; Xu, L.; Li, X. Molecular Characterisation and the Protective Immunity Evaluation of Eimeria maxima Surface Antigen Gene. Parasit. Vectors 2018, 11, 325.

- Chen, H.; Huang, C.; Chen, Y.; Mohsin, M.; Li, L.; Lin, X.; Huang, Z.; Yin, G. Efficacy of Recombinant N- and C-Terminal Derivative of EmIMP1 against E. maxima Infection in Chickens. Br. Poult. Sci. 2020, 61, 518–522.

- Jenkins, M.C.; Fetterer, R.; Miska, K.; Tuo, W.; Kwok, O.; Dubey, J.P. Characterization of the Eimeria maxima Sporozoite Surface Protein IMP1. Vet. Parasitol. 2015, 211, 146–152.

- da Silva, J.T.; Alvares, F.B.V.; de Lima, E.F.; Filho, G.M.d.S.; da Silva, A.L.P.; Lima, B.A.; Feitosa, T.F.; Vilela, V.L.R. Prevalence and Diversity of Eimeria spp. in Free-Range Chickens in Northeastern Brazil. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 1031330.

- Xu, L.; Xiang, Q.; Li, M.; Sun, X.; Lu, M.; Yan, R.; Song, X.; Li, X. Pathogenic Effects of Single or Mixed Infections of Eimeria mitis, Eimeria necatrix, and Eimeria tenella in Chickens. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 657.

- Huang, X.; Liu, J.; Tian, D.; Li, W.; Zhou, Z.; Huang, J.; Song, X.; Xu, L.; Yan, R.; Li, X. The Molecular Characterization and Protective Efficacy of Microneme 3 of Eimeria mitis in Chickens. Vet. Parasitol. 2018, 258, 114–123.

- Su, S.; Hou, Z.; Liu, D.; Jia, C.; Wang, L.; Xu, J.; Tao, J. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis of Second- and Third-Generation Merozoites of Eimeria necatrix. Parasit. Vectors 2017, 10, 388.

- Qu, G.; Xu, Z.; Tuo, W.; Li, C.; Lillehoj, H.; Wan, G.; Gong, H.; Huang, J.; Tian, G.; Li, S.; et al. Immunoproteomic Analysis of the Sporozoite Antigens of Eimeria necatrix. Vet. Parasitol. 2022, 301, 109642.

- 105. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. National Library of Medicine. Available online: https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi (accessed on 19 December 2022).

- Song, X.; Gao, Y.; Xu, L.; Yan, R.; Li, X. Partial Protection against Four Species of Chicken Coccidia Induced by Multivalent Subunit Vaccine. Vet. Parasitol. 2015, 212, 80–85.

- Brothers, V.M.; Kuhn, I.; Paul, L.S.; Gabe, J.D.; Andrews, W.H.; Sias, S.R.; McCaman, M.T.; Dragon, E.A.; Files, J.G. Characterization of a Surface Antigen of Eimeria tenella Sporozoites and Synthesis from a Cloned CDNA in Escherichia coli. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1988, 28, 235–247.

- He, X.; Grigg, M.E.; Boothroyd, J.C.; Garcia, K.C. Structure of the Immunodominant Surface Antigen from the Toxoplasma gondii SRS Superfamily. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2002, 9, 606–611.

- Võ, T.C.; Naw, H.; Flores, R.A.; Lê, H.G.; Kang, J.M.; Yoo, W.G.; Kim, W.H.; Min, W.; Na, B.K. Genetic Diversity of Microneme Protein 2 and Surface Antigen 1 of Eimeria tenella. Genes 2021, 12, 1418.

- Chow, Y.P.; Wan, K.L.; Blake, D.P.; Tomley, F.; Nathan, S. Immunogenic Eimeria tenella Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-Anchored Surface Antigens (SAGs) Induce Inflammatory Responses in Avian Macrophages. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e25233.

- Han, H.Y.; Lin, J.J.; Zhao, Q.P.; Dong, H.; Jiang, L.L.; Xu, M.Q.; Zhu, S.H.; Huang, B. Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes in Early Stages of Eimeria tenella by Suppression Subtractive Hybridization and CDNA Microarray. J. Parasitol. 2010, 96, 95–102.

- Liu, L.; Xu, L.; Yan, F.; Yan, R.; Song, X.; Li, X. Immunoproteomic Analysis of the Second-Generation Merozoite Proteins of Eimeria tenella. Vet. Parasitol. 2009, 164, 173–182.

- Walker, R.A.; Sharman, P.A.; Miller, C.M.; Lippuner, C.; Okoniewski, M.; Eichenberger, R.M.; Ramakrishnan, C.; Brossier, F.; Deplazes, P.; Hehl, A.B.; et al. RNA Seq Analysis of the Eimeria tenella Gametocyte Transcriptome Reveals Clues about the Molecular Basis for Sexual Reproduction and Oocyst Biogenesis. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 94.

- Ramly, N.Z.; Dix, S.R.; Ruzheinikov, S.N.; Sedelnikova, S.E.; Baker, P.J.; Chow, Y.P.; Tomley, F.M.; Blake, D.P.; Wan, K.L.; Nathan, S.; et al. The Structure of a Major Surface Antigen SAG19 from Eimeria tenella Unifies the Eimeria SAG Family. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 376.

- Niderman, T.; Genetet, I.; Bruyere, T.; Gees, R.; Stintzi, A.; Legrand, M.; Fritig, B.; Mosinger, E. Pathogenesis-Related PR-1 Proteins Are Antifungal (Isolation and Characterization of Three 14-Kilodalton Proteins of Tomato and of a Basic PR-1 of Tobacco with Inhibitory Activity against Phytophthora Infestans). Plant. Physiol. 1995, 108, 17–27.

- Klessig, D.F.; Durner, J.; Noad, R.; Navarre, D.A.; Wendehenne, D.; Kumar, D.; Zhou, J.M.; Shah, J.; Zhang, S.; Kachroo, P.; et al. Nitric Oxide and Salicylic Acid Signaling in Plant Defense. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 8849–8855.

- Morrissette, J.; Krätzschmar, J.; Haendler, B.; el-Hayek, R.; Mochca-Morales, J.; Martin, B.M.; Patel, J.R.; Moss, R.L.; Schleuning, W.D.; Coronado, R. Primary Structure and Properties of Helothermine, a Peptide Toxin That Blocks Ryanodine Receptors. Biophys. J. 1995, 68, 2280–2288.

- Wang, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Zhu, S.; Huang, B.; Yu, S.; Liang, S.; Wang, H.; Zhao, H.; Han, H.; Dong, H. Further Investigation of the Characteristics and Biological Function of Eimeria tenella Apical Membrane Antigen 1. Parasite 2020, 27, 70.

- Li, C.; Zhao, Q.; Zhu, S.; Wang, Q.; Wang, H.; Yu, S.; Yu, Y.; Liang, S.; Zhao, H.; Huang, B.; et al. Eimeria tenella Eimeria-Specific Protein That Interacts with Apical Membrane Antigen 1 (EtAMA1) Is Involved in Host Cell Invasion. Parasit. Vectors 2020, 13, 373.

- Pastor-Fernández, I.; Kim, S.; Billington, K.; Bumstead, J.; Marugán-Hernández, V.; Küster, T.; Ferguson, D.J.P.; Vervelde, L.; Blake, D.P.; Tomley, F.M. Development of Cross-Protective Eimeria-Vectored Vaccines Based on Apical Membrane Antigens. Int. J. Parasitol. 2018, 48, 505–518.

- Tomley, F.M.; Soldati, D.S. Mix and Match Modules: Structure and Function of Microneme Proteins in Apicomplexan Parasites. Trends Parasitol. 2001, 17, 81–88.