Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yongqiang Wen | -- | 607 | 2023-06-04 03:05:38 | | | |

| 2 | Yongqiang Wen | + 3289 word(s) | 3743 | 2023-06-05 04:48:50 | | | | |

| 3 | Peter Tang | Meta information modification | 3743 | 2023-06-05 04:59:14 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Wen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Zhao, B.; Wang, J. Pharmacological Efficacy of Baicalin in Inflammatory Diseases. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/45167 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Wen Y, Wang Y, Zhao C, Zhao B, Wang J. Pharmacological Efficacy of Baicalin in Inflammatory Diseases. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/45167. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Wen, Yongqiang, Yazhou Wang, Chenxu Zhao, Baoyu Zhao, Jianguo Wang. "Pharmacological Efficacy of Baicalin in Inflammatory Diseases" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/45167 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Wen, Y., Wang, Y., Zhao, C., Zhao, B., & Wang, J. (2023, June 04). Pharmacological Efficacy of Baicalin in Inflammatory Diseases. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/45167

Wen, Yongqiang, et al. "Pharmacological Efficacy of Baicalin in Inflammatory Diseases." Encyclopedia. Web. 04 June, 2023.

Copy Citation

Baicalin is one of the most abundant flavonoids found in the dried roots of Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi (SBG) belonging to the genus Scutellaria. Baicalin is demonstrated to have anti-inflammatory, antiviral, antitumor, antibacterial, anticonvulsant, antioxidant, hepatoprotective, and neuroprotective effects.

baicalin

bioavailability

drug interaction

anti-inflammatory activity

pharmacokinetics

1. Introduction

Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi (SBG), belonging to the genus Scutellaria, grows mainly in Asia, including China, Mongolia, Japan, Korea, and Siberia [1]. In China, SBG is regarded as an authentic traditional medicinal herb that grows widely in desert areas and sunny grassy slopes at altitudes of 60–2000 m [2]. It is mainly found in northern provinces of China such as Hebei, Shandong, Shanxi, and Inner Mongolia [3]. Based on SBG’s growing season and cycle characteristics, Xu et al. (2020) determined that the quality of SBG harvested in autumn and cultivated for three years was the best [2]. The primary active constituents of SBG encompass baicalin, baicalein, wogonin, Han baicalin, and Han baicalein [4]. In the field of clinical practice, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi is frequently employed to treat inflammatory disorders, influenza, diarrhea, jaundice, headache, and abdominal pain [5]. The broad-spectrum pharmacological effect of SBG in diminishing various kinds of diseases is mainly through regulating host immunity [6]. In addition, SBG was reported to have effects such as enhancing immunity, anti-aging, protecting the liver, and anti-osteoporosis [7][8].

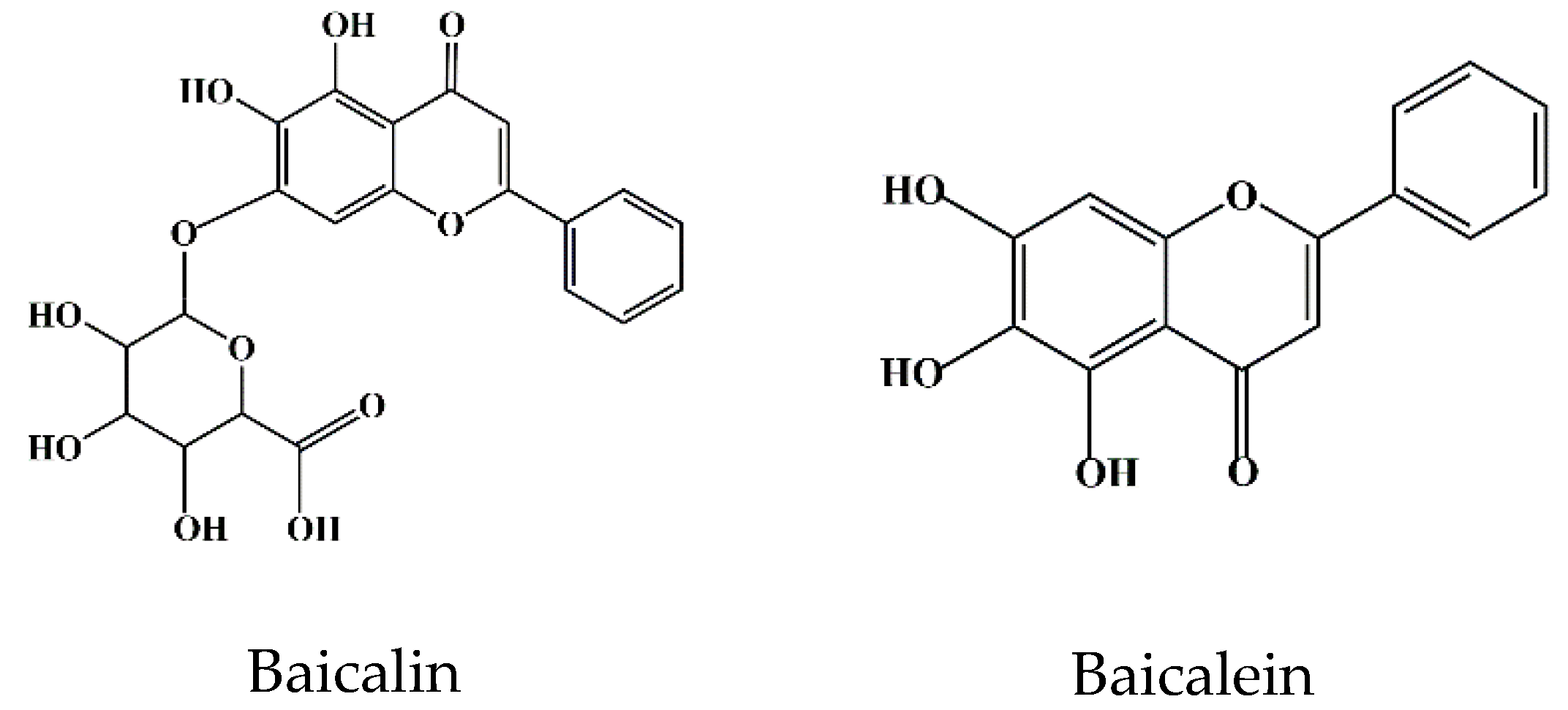

Flavonoids are a class of compounds that are widely distributed in various vegetables and fruits [9]. The consumption of flavonoid-rich fruits and vegetables could reduce the risk of inflammatory diseases [9]. In vivo and in vitro analyses have confirmed that certain flavonoids play a therapeutic effect on diseases. For example, baicalin (7-glucuronic acid, 5,6-dihydroxy-flavone, C21H18O11) has been widely used in recent years for the development of pharmaceutical formulations and the treatment of certain diseases [10]. Baicalin, also known as begalin, is formed by combining the C7 hydroxyl group of baicalein with glucuronic acid [10] (Figure 1). Baicalin is a light-yellow powder under normal conditions; it is bitter in taste, insoluble in alcohols, and soluble in chloroform, nitrobenzene, dimethyl sulfoxide, etc. [11][12][13]. For the function of baicalin, studies have demonstrated that baicalin, containing most of the pharmacological function of SBG in modulating host immunity, plays a therapeutic role in neuroinflammation, enteritis, pneumonia, secondary inflammation, and other diseases in the clinic [14][15][16]. Inflammation is an immune response to invasiveness, which aims to clear away invasive pathogens and initiates tissue repair [17]. Although inflammation has this protective function, inappropriate inflammation can trigger damage to the body and induce the development of diseases [18]. Baicalin has been demonstrated to have anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory functions, most of which are regulated by inhibiting the activation of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) signaling pathway and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor pyrin domain protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome as well as suppressing pro-inflammatory factor expression, such as interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, IL-8, tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), etc. [1][17].

Figure 1. Chemical structure of baicalin and baicalein.

In summary, the pharmacological effects of baicalin are closely related to inhibiting inflammatory reactions. In this entry, the basic physicochemical properties of baicalin and its molecular and immune regulatory mechanisms in the prevention and treatment of inflammatory diseases are reviewed.

2. Bioavailability of Baicalin

In pharmacological studies, bioavailability refers to the degree of drug absorbed into the systemic circulation, reflecting the percentage of drug absorbed by the gastrointestinal tract to the oral amount [19]. Generally, the permeability coefficient of drugs with 1% absorption is about 1.0 × 10−6 cm/s. The permeability coefficient of drugs absorbed between 1% and 100% ranges from 1.0 × 10−6 to 0.1 cm/s, and the permeability coefficient of drugs and peptides absorbed less than 1% is below 1.0 × 10−7 cm/s [20].

Its low water solubility (67.03 ± 1.60 μg/mL) and permeability (0.037 × 10−6 cm/m) determine that baicalin cannot be transported by passive diffusion into the host cell lipid bilayer, which results in poor absorption and the low bioavailability of baicalin [21]. Contrarily, baicalein, a glycoside form of baicalin with good permeability and lipophilicity, can be well absorbed by the gastrointestinal tract [22]. Studies have shown that there is an interconversion between baicalin and baicalein during the absorption process of baicalin [22][23][24]. In particular, after drug administration in animals, baicalin could be hydrolyzed to baicalein by β-glucuronidase derived from intestinal bacteria, and baicalein could be recovered to baicalin by uridine 5′-diphosphate (UDP) glucuronide transferase (UGT) circulating in vivo [25]. This mutual conversion maximizes the full pharmacodynamic functions of baicalin [25]. Due to the better absorption of baicalein compared to baicalin, the conversion of baicalin to baicalein is a key step for the absorption of baicalin in the intestine. Furthermore, the intestinal microbiota was reported to be associated with the conversion of baicalin to baicalein [26]. For instance, the intestinal absorption of baicalin in germ-free rats was significantly reduced compared to conventional rats [26], suggesting that the presence of intestinal flora was conducive to the body’s absorption and utilization of baicalin. In other words, only a small proportion of baicalin is absorbed by the physical body as a raw component, and most of it is hydrolyzed into baicalein by bacteria and absorbed by the physical body. Human serum albumin (HSA) is the main transport medium through which flavonoids (for example, baicalin, catechin, quercetin, etc.) are absorbed and utilized by the physical body [27]. The rate of transport and volume distribution of baicalin in the host depends on the binding degree of baicalin to HSA [28]. Especially, it was confirmed that, based on the area under the time–concentration curve, the relative absorption rate of baicalin was approximately 65% [29]. Further pharmacokinetic analysis showed that the peak concentration of baicalin in rat serum was lower than that of baicalein [30]. To improve the bioavailability of baicalin, investigators focused on the development of new formulations of baicalin, such as solid nanocrystal nano-emulsions, solid–liquid nanoparticles, liposome formulations, phospholipid complex hydrogels, etc. [31][32][33]. The application development of these new technologies and products aims to improve the solubility and absorption of baicalin.

3. Toxicity of Baicalin

Clearing the safe dose range and action time of drugs is crucial for drug properties, as these directly threaten animals’ safety. The determination of baicalin’s safe dosage range and its duration of action holds paramount significance across diverse animal and cellular models [34]. To investigate whether baicalin was involved in the regulation of hepatic insulin resistance and gluconeogenic activity, an ex in vivo study showed that intraperitoneal injection of baicalin (50 mg/kg) not only resulted in body weight loss and insulin resistance (Homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance, HOMA-IR) in obese mice (C57BL/6J) but also reduced glucose intolerance and hyperglycemia. In this study, they also showed that baicalin was not toxic to mice’s liver [35]. In line, baicalin was found to effectively alleviate the development of obesity by inhibiting the expression of p-p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), phosphorylation cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate (cAMP) response binding protein (p-CREB), forkhead transcription factor forkhead box O1A (Foxo1), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivators 1α (PGC-1α), phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK), and glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase) in the liver of obese mice and hepatocytes [35]. Another study performed by Shi et al. (2020) demonstrated that liver toxicity induced by acetaminophen (APAP) in mice was effectively reduced at 6 h, 12 h, and 18 h after baicalin administration, and the necrotic area of liver cells was significantly reduced in mice administrated with 40 mg/kg baicalin [36]. These results indicate that baicalin at a safe dose not only has no cytotoxicity in mice but can also reduce lipotoxicity. In line with this, baicalin was reported to effectively inhibit the occurrence of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced hepatitis in chickens treated with 50, 100, and 200 mg/kg baicalin [37]. An oxidative stress study in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), revealed that baicalin at concentrations ranging from 0.01 nM to 100 μM did not exhibit any cytotoxic effects on HepG2 cells at 24 h and 48 h, as determined by the cholecystokinin (CCK)-8 assay [38].

Baicalin has a significant inhibitory effect on endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. For instance, baicalin (12.5 μM and 25 μM) was found to effectively inhibit the expression of ER stress marker phosphorylated inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (p-IRE1α) and reverse palmitic acid (PA)-induced apoptosis and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production [38]. The main mechanism might be because baicalin reduced PA-induced cytotoxicity by inhibiting ER stress and the activation of thioredoxin-interacting protein (Txnip)/NLRP12 inflammasome [39]. These studies provide a new theoretical basis for the clinical application of baicalin and further improve the cytotoxicity study of baicalin. From a toxicological point of view, baicalin is more toxic than baicalein [39]. Interestingly, intestinal microorganisms might have a protective effect on hepatotoxicity caused by baicalin [39]. To support this, incubation of baicalin with fecal enzymes diminished the cytotoxicity to hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) cells in a dose-dependent manner, suggesting that the conversion from baicalin to baicalein by human fecal enzymes protects against baicalin-induced cytotoxicity to HepG2 cells [40][41]. These studies pave a new theoretical basis for the clinical application of baicalin and further improve the cytotoxicity studies of baicalin.

4. Therapeutic Effects of Baicalin

4.1. Effect of Baicalin on Hepatitis

TNF-α is an important cytokine involved in metabolic diseases such as obesity, insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, and NAFLD [42]. The production of TNF-α in the process of liver injury causes the release of IL-1β and IL-6, which mediates inflammatory response [43]. Hepatotoxicity could activate the toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) through excessive lipid accumulation in hepatocytes [44]. Upon activation of TLR4, a large amount of MyD88 aggregates NF-κB and MAPK [45]. The aggregations of NF-κB and MAPK promote the expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and other pro-inflammatory factors and the infiltration of pro-inflammatory cells, which further aggravates liver injury [46]. For instance, studies showed that baicalin could reduce the expressions levels of TNF-α and NF-κB in liver tissue and the production of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in plasma, thus reducing the degree of liver inflammation [47][48]. In line with this, baicalin reduced systemic inflammation by blocking the NLR pyrin domain containing 3-Gasdermin D signal transduction and by inhibiting TLR4 signal cascade in mice, reducing the release of pro-inflammatory factors (TNF-α, IL-8, and IL-6) [36][37][49]. In addition, studies found that baicalin can initiate the repair of liver injury caused by acetaminophen (APAP) [50]. The main mechanism is to promote liver regeneration after APAP-induced acute liver injury in mice by inducing the accumulation of nuclear factor erythroid2-related factor 2 (NRF2) in the cytoplasm and the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome, which in turn leads to the increase in IL-18 expression and the proliferation of hepatocytes, thus achieving liver-regeneration function [36][50].

4.2. Role of Baicalin in Rheumatoid Arthritis

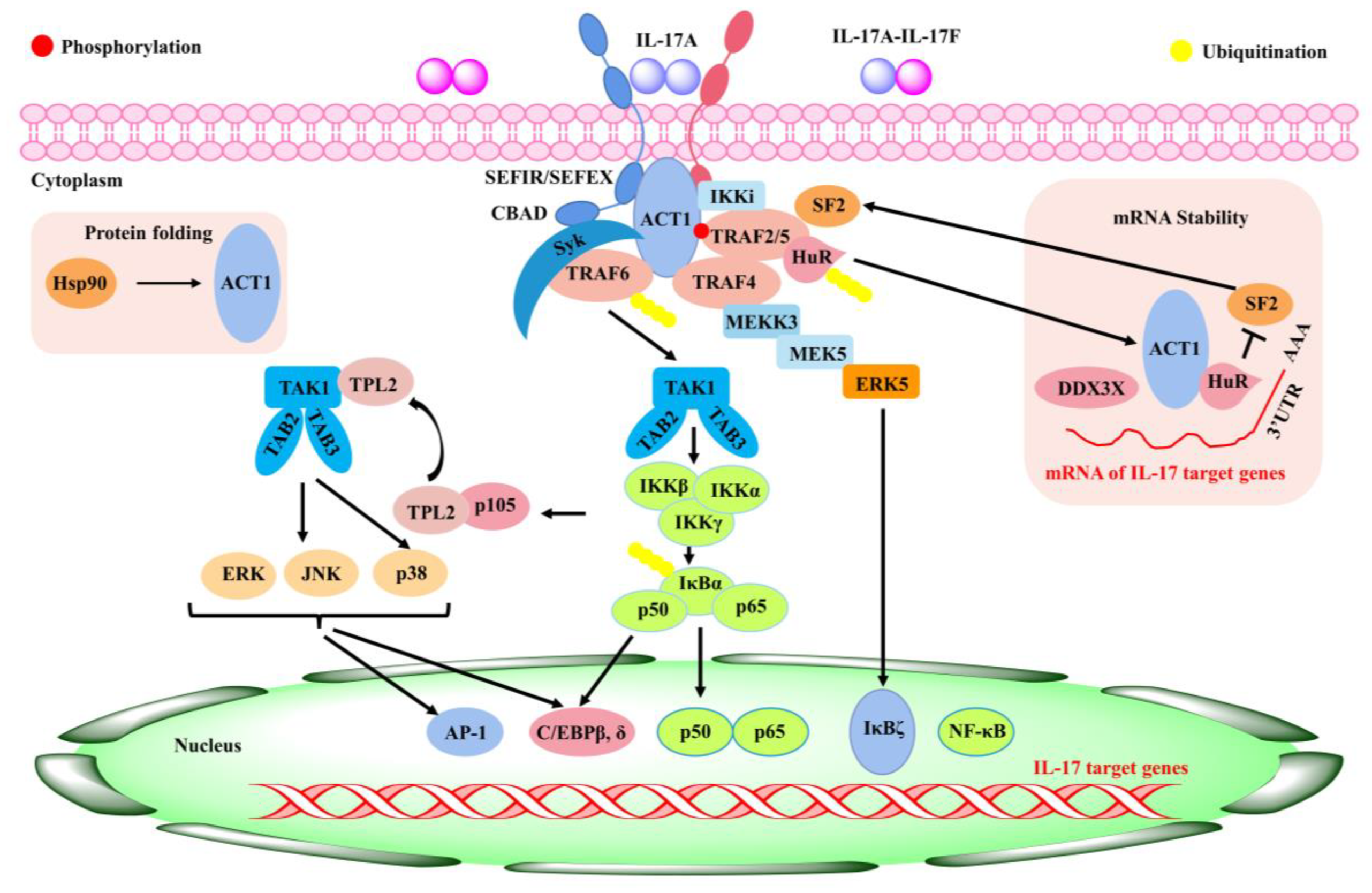

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory disease in the synovium, which can lead to cartilage and bone damage and disability [51]. Factors involved in the development of diseases include genetic factors, infections, and immune dysfunction [52][53]. Currently, RA is managed clinically with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), immunosuppressive drugs, etc. [54]. During the onset and spread of RA, immune T and B lymphocytes activate the effector cells and then release pro-inflammatory mediators such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-17, and TNF-α, which are primarily responsible for synovial joint inflammation and bone erosion [54]. IL-17 is an important cytokine produced by T helper 17 cells (Th17) [55]. As a potent inflammatory cytokine, it could induce the production of a variety of pro-inflammatory factors such as IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β, all of which can lead to an inflammatory response in tissues and cells [56] and a significant increase in IL-17 in both the serum and joint fluid of RA patients relative to osteoarthritis [57]. The production of a range of chemokines induced by IL-17 led to the recruitment of T cells, B cells, monocytes, and neutrophils in diseased joints [58]. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPS), nitric oxide (NO), and nuclear factor-κB (RANK)/RANK ligand (RANKL) receptor activators can be upregulated by IL-17 in both cartilage and osteoblasts, leading to damage in bone and articular cartilage and promoting the development of RA [59][60]. Therefore, inhibition of IL-17 expression might be an important target to improve RA (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Inflammatory signaling mediated by IL-17 [61].

Inactivated Mycobacterium tuberculosis adjuvant-induced arthritis in mice showed that intraperitoneal administration of 100 mg/kg baicalin significantly inhibited the expansion of the spleen Th17 cell population (40%) and attenuated arthritic symptoms such as paw and ankle swelling [62]. A molecular mechanism study showed that baicalin inhibited the expression of the retinoid-related orphan nuclear receptor γt (RORγt) gene, a key transcription factor for Th17 cell differentiation [63]. Furthermore, baicalin treatment in IL-17-contaminated synovial cells for 24 h significantly inhibited lymphocyte adhesion to synovial cells, blocked IL-17-induced inflammatory cascade, and reduced the expression of intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM-1), IL-6, and TNF-α [62]. Additionally, Tong et al. (2018) found that baicalin reduced TLR2 and MyD88 gene expression and the toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88), and NF-κB-p65 protein expression in RA synovial fibroblasts (RA-FLS) [64], suggesting that the mechanism of baicalin’s action might be related to the inhibition of the TLR2/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway. The above studies suggest that baicalin has a positive effect in alleviating RA disease, but more detailed mechanisms of action need to be further investigated.

4.3. Anti-Inflammatory Role of Baicalin in Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes

Obesity refers to excessive total or local fat in the body, which is a “metabolic syndrome” with indicators such as abnormal blood glucose, blood fat, blood pressure, and insulin resistance (IR) [65]. Excessive nutrient intake and lack of exercise are likely to cause obesity, which is associated with insulin resistance and an increased risk of type 2 diabetes [66]. It was established that excessive white adipose tissue (WAT) is associated with the occurrence of chronic, low-grade, and systemic inflammation [67]. NF-κB, as a major pro-inflammatory nuclear transcription factor, directly increases the expression level of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines [68]. The inactive state of NF-κB is chelated with a complex of inhibitor-κB (IKB) inhibitor protein family members in the cytoplasm [68]. Upon cellular activation, IκB kinase β (IKK-β) phosphorylates IκB, leading to its ubiquitination and proteolytic degradation. This in turn releases and translocates NF-κB to the nucleus and further activates target gene transcription in the nucleus [68]. Thus, inhibition of the NF-κB signaling pathway in adipose tissue reduces the incidence of chronic, low-grade, and systemic inflammation and confers a protective mechanism against the development and progression of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes [68].

In most cases, obesity develops from regularly eating a high-fat diet (HFD), and excess obesity can lead to fatty liver disease, known as “NAFLD” [69]. Overexpression of adiponectin, leptin, and TNF-α is a major factor increasing the risk of liver fat accumulation, insulin resistance, pancreatic beta cell dysfunction, and fibrosis [70][71]. Baicalin was shown to reduce the degree of fatty liver degeneration and obesity in a dose-dependent manner, which was attributed to baicalin-dependent inhibition of the hepatic calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase beta (CaMKKβ)/Adenosine 5‘-monophosphate -activated protein ki-nase (AMPK)/acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) pathway [12]. Therefore, AMPK activators may be an effective target for the treatment of obesity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes is an important cause of endocrine and metabolic disorders. Long-term hyperglycemia can cause a variety of chronic complications such as diabetic nephropathy and diabetic retinopathy [72][73]. Studies have shown that baicalin can effectively improve diabetic nephropathy, mainly by activating the NRF2-mediated antioxidant signaling pathway and inhibiting the MAPK-mediated inflammatory signaling pathway [72][73]. In support of this, baicalin was reported to significantly reduce the expression of pro-inflammatory factors IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α through the MAPK pathway [72][73]. Because of the important clinical significance of baicalin in the prevention and treatment of obesity and diabetes, more and more attention is focused on baicalin in obesity and diabetes.

4.4. Role of Baicalin in Respiratory-Related Inflammation

Over the past few years, respiratory diseases have become more prevalent, posing a significant threat to human health and safety. The commonly occurring respiratory diseases include asthma, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) [74]. Asthma, which is recognized as reversible airway obstruction induced by persistent airway inflammation, is caused by airborne pollutants and genetic predisposition factors [75]. IPF or pulmonary fibrosis (PF), characterized by fibroblast proliferation and collagen deposition in lung tissue structure, is a chronic interstitial lung disease caused by pneumonia, excessive smoking, and/or other factors, leading to structural destruction and respiratory failure [76]. Relevant studies reported that a class of small non-coding RNA molecules, such as microRNA-21 (miR-21) [77], miR-29, and miR-155, all involving the progression of IPF, is upregulated by pro-inflammatory cytokines and transforming growth factor β-1 (TGF-β1) [28][74][78]. Baicalin is an effective treatment in patients with respiratory tract diseases [79]. A study in bleomycin (5 U/kg)-induced PF mice showed that intraperitoneal injection of baicalin (120 mg/kg/d) reduced lung fibrosis, collagen deposition, and hydroxyproline levels in lung tissue through reducing TGFβ1-induced extracellular signal-regulated kinaes 1/2 (ERK1/2) signaling compared with the control [79]. To investigate baicalin’s anti-fibrosis effect, a study in mice with knocked-out adenosine A2a receptor (A2aR), which is an inflammatory regulatory receptor, found that, compared with A2aR-positive mice, A2aR-knockout mice had more severe pulmonary fibrosis and higher expression levels of TGF-β1 and phosphorylated ERK1/2 protein [79]. Based on these results, the authors proposed that baicalin might exert its antifibrotic effect by downregulating the elevated levels of TGFβ1 and pERK1/2 and promoting the expression of inflammatory regulatory gene A2aR [79]. The A2aR gene expressed in macrophages, dendritic cells, T cells, B cells, and epithelial cells is considered a novel regulator of inflammation and tissue repair [80]. PAH is characterized by right ventricular hypertrophy and dysfunction due to the deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) protein collagen fibers on the walls of pulmonary arterioles, which further leads to constriction of pulmonary blood vessels [81]. In a related baicalin study, the results in rats with chronic hypoxia pretreated with baicalin (30 mg/kg) showed inhibition of p38 MAPK and a downregulation of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) expression in pulmonary arterioles, thus alleviating PAH and pulmonary heart disease (right-side cardiac dysfunction) [80]. In addition, baicalin was reported to reduce the expression levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in lung tissue by regulating the p38 MAPK signaling pathway, suggesting an anti-inflammatory role of baicalin [82].

4.5. Therapeutical Effects of Baicalin in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic immune disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of abdominal pain, diarrhea, and purulent stool [83]. IBD mainly includes Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) [84][85][86]. Baicalin plays a protective role in IBD by inhibiting oxidative stress, immune regulation, and anti-inflammatory properties [87]. To support this, baicalin was found to affect inflammatory processes by regulating autophagy and the NF-κB signaling pathway in intestinal epithelial cells, thereby improving paracellular permeability [88]. In line with this, baicalin was reported to attenuate the inflammatory response by modulating the polarization of M1 macrophages towards the M2 phenotype in a dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced ulcerative colitis model [84]. Similarly, it was found that baicalin downregulated inflammatory cytokines’ expression of IL-1β, TNF-α, apoptotic genes Bcl-2, and caspase-9 in the colon of 2,4,6-trinitrobenzesulfonic acid (TNBS)-induced UC rats in a dose-dependent fashion [89]. The treatment of baicalin in inflammation is mainly mediated by suppressing the inhibitor-κB (IKB) kinase complex (IKK)/IKB/NF-κB signaling pathway [89]. Especially, the administration of baicalin (5–20 mg/kg) in TNBS-induced UC rats downregulated the expression of TNF-α and IL-6 and inhibited the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway, thereby alleviating UC [90]. Consistently, baicalin (30–120 mg/kg) was reported to have a therapeutic effect in TNBS-induced UC by promoting the activities of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-PX) and by reducing the content of malondialdehyde (MDA) [91]. This study further found that baicalin (100 mg/kg) reduced the production of IL-6, IL-1β, and IL-17 in serum and inhibited the activation of SOD, GSH-PX, and MDA in the UC model under high temperature and humidity [91]. These results suggest that the anti-inflammatory effect of baicalin is attributed to inhibiting the activation of the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways.

In addition, baicalin (50–150 mg/kg) administration decreased myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity, NO content, and the expression of TNF and IL-6 in the colon of DSS-induced UC rats [92]. Another study showed that baicalin (100 mg/kg) attenuated DSS-induced UC by blocking the TLR-4/NF-κB-p65/IL-6 signaling pathway and inhibiting inflammatory cytokines’ expression of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-13 [93]. Consistently, baicalin (10 mg/kg) downregulated the expression of macrophage migration inhibitors monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1 and macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-3a in rat colons of a TNBS-induced UC model [94]. The balance of Th17/regulatory T cells (Treg) has been demonstrated to be associated with UC [95]. For instance, baicalin (20–100 mg/kg) regulated the balance of Th17/Treg by inhibiting MDA and ROS production, reducing GSH and SOD levels, and downregulating the expression of Th17-related factors IL-6 and IL-17 in TNBS-induced UC rats [96][97]. In clinical studies of UC patients, baicalin regulated immune balance and relieved the UC-induced inflammation reaction by promoting the proliferation of CD4(+) CD29(+) cells and modulating immunosuppressive pathways [98].

4.6. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Baicalin in Cardiovascular Diseases

Inflammation is an important link with the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases such as myocardial fibrosis, atherosclerosis (AS), and myocardial depression, and it plays a crucial role in the further development of disease [99]. AS, the pathological basis of cardiovascular disease, could cause angina pectoris and myocardial infarction, etc. [100]. The main pathological mechanism involved is an endothelial function, lipid deposition, oxidative stress damage, immune inflammation, etc. [101][102]. Baicalin is widely used in lipid-lowering studies because of its effectiveness in reducing serum total cholesterol (TC), triacylglycerol (TG), and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels [103]. In an apolipoprotein E (APOE)−/− mouse model of a high-cholesterol diet, baicalin reduced the expression of TG and LDL-C [104]. Their further analysis showed that baicalin promoted the proliferation and viability of Treg cells and the expression of TGF-β and IL-10, which improved the progression of atherosclerotic lesions through lipid regulation and immunomodulation [105]. In the development of AS-induced inflammation, activation of NF-κB increased the production of inflammatory factors and chemokines [106]. Therefore, baicalin has a beneficial effect on the development of AS by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway [107]. It was also shown that baicalin mediated the Wnt1/dickkopf-related protein 1 (DKK1) signaling pathway to prevent AS [108]. In addition, the Th17/Treg balance is inextricably linked to the development of AS, and IL-17A secreted by Th17 triggers the onset of AS-induced inflammation and Treg, a protective T cell, which effectively attenuates the inflammatory response [109]. Patients with AS commonly have a Th17/Treg imbalance; specifically, Th17 cells increase, and Treg cells decrease [110]. Studies conducted by Jiang et al. (2019) and Yang et al. (2012) showed that baicalin had a protective effect on Th17/Treg homeostasis, which is associated with its anti-AS role [111][112]. In hypertension studies, baicalin reduced hypertension-induced inflammation (significant reduction in IL-1β and IL-6) by increasing the expression of tight-junction proteins that could maintain intestinal integrity [113]. Baicalin could also lower blood pressure by lowering calcium levels and causing vascular smooth muscle diastole [114]. In summary, baicalin has a combined effect on the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease.

References

- Liao, H.; Ye, J.; Gao, L.; Liu, Y. The main bioactive compounds of Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi. for alleviation of inflammatory cytokines: A comprehensive review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 133, 110917.

- Xu, N.; Meng, F.; Zhou, G.; Li, Y.; Lu, H. Assessing the suitable cultivation areas for Scutellaria baicalensis in China using the Maxent model and multiple linear regression. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2020, 90, 104052.

- Han, L.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, X.; Huang, J.; Wang, G.; Zhou, C.; Dong, J.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, H.; et al. A candidate drug screen strategy: The discovery of oroxylin a in scutellariae radix against sepsis via the correlation analysis between plant metabolomics and pharmacodynamics. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 861105.

- De, S.; Paul, S.; Manna, A.; Majumder, C.; Pal, K.; Casarcia, N.; Mondal, A.; Banerjee, S.; Nelson, V.K.; Ghosh, S.; et al. Phenolic phytochemicals for prevention and treatment of colorectal cancer: A critical evaluation of in vivo studies. Cancers 2023, 15, 993.

- Zhao, Q.; Chen, X.-Y.; Martin, C. Scutellaria baicalensis, the golden herb from the garden of Chinese medicinal plants. Sci. Bull. 2016, 61, 1391–1398.

- Hong, G.-E.; Kim, J.-A.; Nagappan, A.; Yumnam, S.; Lee, H.-J.; Kim, E.-H.; Lee, W.-S.; Shin, S.-C.; Park, H.-S.; Kim, G.-S. Flavonoids Identified from Korean Scutellaria baicalensis georgi inhibit inflammatory signaling by suppressing activation of NF-κB and MAPK in RAW 264.7 cells. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 912031.

- Kwon, B.-E.; Song, J.-H.; Song, H.-H.; Kang, J.W.; Hwang, S.N.; Rhee, K.-J.; Shim, A.; Hong, E.-H.; Kim, Y.-J.; Jeon, S.-M.; et al. Antiviral activity of oroxylin a against coxsackievirus b3 alleviates virus-induced acute pancreatic damage in mice. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e155784.

- Dong, Q.; Chu, F.; Wu, C.; Huo, Q.; Gan, H.; Li, X.; Liu, H. Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi extract protects against alcohol-induced acute liver injury in mice and affects the mechanism of ER stress. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 13, 3052–3062.

- Tao, H.; Zhao, Y.; Li, L.; He, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Hong, G. Comparative metabolomics of flavonoids in twenty vegetables reveal their nutritional diversity and potential health benefits. Food Res. Int. 2023, 164, 112384.

- Dai, J.; Liang, K.; Zhao, S.; Jia, W.; Liu, Y.; Wu, H.; Lv, J.; Cao, C.; Chen, T.; Zhuang, S.; et al. Chemoproteomics reveals baicalin activates hepatic CPT1 to ameliorate diet-induced obesity and hepatic steatosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E5896–E5905.

- De Oliveira, M.R.; Nabavi, S.F.; Habtemariam, S.; Erdogan, O.I.; Daglia, M.; Nabavi, S.M. The effects of baicalein and baicalin on mitochondrial function and dynamics: A review. Pharmacol. Res. 2015, 100, 296–308.

- Xi, Y.; Wu, M.; Li, H.; Dong, S.; Luo, E.; Gu, M.; Shen, X.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H. Baicalin attenuates high fat diet-induced obesity and liver dysfunction: Dose-response and potential role of CaMKKβ/AMPK/ACC pathway. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 35, 2349–2359.

- Li, H.-B.; Chen, F. Isolation and purification of baicalein, wogonin and oroxylin a from the medicinal plant Scutellaria baicalensis by high-speed counter-current chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2005, 1074, 107–110.

- Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Feng, X.; Nwafor, E.-O.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, R.; Dang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, C.; et al. Baicalin-berberine complex nanocrystals orally promote the co-absorption of two components. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2022, 12, 3017–3028.

- Yu, M.; Han, S.; Wang, M.; Han, L.; Huang, Y.; Bo, P.; Fang, P.; Zhang, Z. Baicalin protects against insulin resistance and metabolic dysfunction through activation of GALR2/GLUT4 signaling. Phytomedicine 2022, 95, 153869.

- Zhou, Y.; Li, R.; Xu, X.; Shen, Q.; Wang, H.; Zeng, Z.; Liu, M.; Wu, G. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of traditional Chinese medicine in the treatment of COVID-19. Curr. Drug Metab. 2022, 23, 508–520.

- Dinda, B.; Dinda, S.; DasSharma, S.; Banik, R.; Chakraborty, A.; Dinda, M. Therapeutic potentials of baicalin and its aglycone, baicalein against inflammatory disorders. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 131, 68–80.

- Behl, T.; Kumar, S.; Singh, S.; Bhatia, S.; Albarrati, A.; Albratty, M.; Meraya, A.M.; Najmi, A.; Bungau, S. Reviving the mutual impact of SARS-COV-2 and obesity on patients: From morbidity to mortality. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 151, 113178.

- Shen, Y.; Zhang, N.; Tian, J.; Xin, G.; Liu, L.; Sun, X.; Li, B. Advanced approaches for improving bioavailability and controlled release of anthocyanins. J. Control. Release 2022, 341, 285–299.

- Artursson, P.; Karlsson, J. Correlation between oral drug absorption in humans and apparent drug permeability coefficients in human intestinal epithelial (Caco-2) cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1991, 175, 880–885.

- Wu, H.; Long, X.; Yuan, F.; Chen, L.; Pan, S.; Liu, Y.; Stowell, Y.; Li, X. Combined use of phospholipid complexes and self-emulsifying microemulsions for improving the oral absorption of a BCS class IV compound, baicalin. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2014, 4, 217–226.

- Kalapos-Kovács, B.; Magda, B.; Jani, M.; Fekete, Z.; Szabó, P.T.; Antal, I.; Krajcsi, P.; Klebovich, I. Multiple ABC transporters efflux baicalin. Phytother. Res. 2015, 29, 1987–1990.

- Noh, K.; Kang, Y.; Nepal, M.R.; Jeong, K.S.; Oh, D.G.; Kang, M.J.; Lee, S.; Kang, W.; Jeong, H.G.; Jeong, T.C. Role of intestinal microbiota in baicalin-induced drug interaction and its pharmacokinetics. Molecules 2016, 21, 337.

- Fong, Y.K.; Li, C.R.; Wo, S.K.; Wang, S.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, L.; Lin, G.; Zuo, Z. In vitro and in situ evaluation of herb–drug interactions during intestinal metabolism and absorption of baicalein. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 141, 742–753.

- Cui, L.; Yuan, T.; Zeng, Z.; Liu, D.; Liu, C.; Guo, J.; Chen, Y. Mechanistic and therapeutic perspectives of baicalin and baicalein on pulmonary hypertension: A comprehensive review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 151, 113191.

- Akao, T.; Kawabata, K.; Yanagisawa, E.; Ishihara, K.; Mizuhara, Y.; Wakui, Y.; Sakashita, Y.; Kobashi, K. Balicalin, the predominant flavone glucuronide of scutellariae radix, is absorbed from the rat gastrointestinal tract as the aglycone and restored to its original form. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2000, 52, 1563–1568.

- Sovrlić, M.; Mrkalić, E.; Jelić, R.; Cendic, S.M.; Stojanović, S.; Prodanović, N.; Tomović, J. Effect of caffeine and flavonoids on the binding of tigecycline to human serum albumin: A spectroscopic study and molecular docking. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 266.

- Liu, H.; Bao, W.; Ding, H.; Jang, J.; Zou, G. Binding modes of flavones to human serum albumin: Insights from experimental and computational studies. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 12938–12947.

- Pang, H.; Wu, T.; Peng, Z.; Tan, Q.; Peng, X.; Zhan, Z.; Song, L.; Wei, B. Baicalin induces apoptosis and autophagy in human osteosarcoma cells by increasing ROS to inhibit PI3K/Akt/mTOR, ERK1/2 and β-catenin signaling pathways. J. Bone Oncol. 2022, 33, 100415.

- Lai, M.-Y.; Hsiu, S.-L.; Tsai, S.-Y.; Hou, Y.-C.; Chao, P.-D.L. Comparison of metabolic pharmacokinetics of baicalin and baicalein in rats. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2003, 55, 205–209.

- Pi, J.; Wang, J.; Feng, X.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yang, W.; Zhang, T.; Guo, P.; Liu, Z.; Qi, D. The Flavonoid components of Scutellaria baicalensis: Biopharmaceutical properties and their improvement using nanoformulation techniques. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2023, 23, 17–29.

- Yadav, N.; Mudgal, D.; Anand, R.; Jindal, S.; Mishra, V. Recent development in nanoencapsulation and delivery of natural bioactives through chitosan scaffolds for various biological applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 220, 537–572.

- Mariadoss, A.; Sivakumar, A.S.; Lee, C.-H.; Kim, S.J. Diabetes mellitus and diabetic foot ulcer: Etiology, biochemical and molecular based treatment strategies via gene and nanotherapy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 151, 113134.

- Li, M.; Shi, A.; Pang, H.; Xue, W.; Li, Y.; Cao, G.; Yan, B.; Dong, F.; Li, K.; Xiao, W.; et al. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of a single ascending dose of baicalein chewable tablets in healthy subjects. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 156, 210–215.

- Fang, P.; Sun, Y.; Gu, X.; Shi, M.; Bo, P.; Zhang, Z.; Bu, L. Baicalin ameliorates hepatic insulin resistance and gluconeogenic activity through inhibition of p38 MAPK/PGC-1α pathway. Phytomedicine 2019, 64, 153074.

- Shi, L.; Zhang, S.; Huang, Z.; Hu, F.; Zhang, T.; Wei, M.; Bai, Q.; Lu, B.; Ji, L. Baicalin promotes liver regeneration after acetaminophen-induced liver injury by inducing NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 160, 163–177.

- Cheng, P.; Wang, T.; Li, W.; Muhammad, I.; Wang, H.; Sun, X.; Yang, Y.; Li, J.; Xiao, T.; Zhang, X. Baicalin alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced liver inflammation in chicken by suppressing TLR4-Mediated NF-κB pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 547.

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Deng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, K. Baicalin protects AML-12 cells from lipotoxicity via the suppression of ER stress and TXNIP/NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2017, 278, 189–196.

- Zhang, S.; Zhong, R.; Tang, S.; Han, H.; Chen, L.; Zhang, H. Baicalin alleviates short-term lincomycin-induced intestinal and liver injury and inflammation in infant mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6072.

- Keumhan, N.; Youra, K.; Mahesh, N.; Ki, J.; Do, O.; Mi, K.; Sangkyu, L.; Wonku, K.; Hye, J.; Tae, J. Role of intestinal microbiota in baicalin-induced drug interaction and its pharmacokinetics. Molecules 2016, 21, 337.

- Khanal, T.; Kim, H.G.; Choi, J.H.; Park, B.H.; Do, M.T.; Kang, M.J.; Yeo, H.K.; Kim, D.H.; Kang, W.; Jeong, T.C. Protective role of intestinal bacterial metabolism against baicalin-induced toxicity in HepG2 cell cultures. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2012, 37, 363–371.

- Felemban, A.H.; Alshammari, G.M.; Yagoub, A.; Al-Harbi, L.N.; Alhussain, M.H.; Yahya, M.A. Activation of AMPK entails the protective effect of royal jelly against high-fat-diet-induced hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in rats. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1471.

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Q.; Jiao, F.; Shi, C.; Pei, M.; Lv, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Gong, Z. TNF-α/HMGB1 inflammation signalling pathway regulates pyroptosis during liver failure and acute kidney injury. Cell Prolif. 2020, 53, e12829.

- Gehrke, N.; Hövelmeyer, N.; Waisman, A.; Straub, B.K.; Weinmann-Menke, J.; Wörns, M.A.; Galle, P.R.; Schattenberg, J.M. Hepatocyte-specific deletion of IL1-RI attenuates liver injury by blocking IL-1 driven autoinflammation. J. Hepatol. 2018, 68, 986–995.

- Long, T.; Liu, Z.; Shang, J.; Zhou, X.; Yu, S.; Tian, H.; Bao, Y. Polygonatum sibiricum polysaccharides play anti-cancer effect through TLR4-MAPK/NF-κB signaling pathways. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 111, 813–821.

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, L.; Liu, M.; Cheng, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Xu, W.; Lu, J.; Liu, J.; Huang, M. Pien-Tze-Huang attenuates neuroinflammation in cerebral ischaemia-reperfusion injury in rats through the TLR4/NF-κB/MAPK pathway. Pharm. Biol. 2021, 59, 828–839.

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Deng, X.; Zhang, N.; Liu, B.; Xin, S.; Li, G.; Xu, K. Baicalin attenuates non-alcoholic steatohepatitis by suppressing key regulators of lipid metabolism, inflammation and fibrosis in mice. Life Sci. 2018, 192, 46–54.

- Liu, J.; Yuan, Y.; Gong, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Q.; Wu, S.; Zhang, X.; Hu, J.; Kuang, G.; Yin, X.; et al. Baicalin and its nanoliposomes ameliorates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease via suppression of TLR4 signaling cascade in mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 80, 106208.

- Zhong, X.; Liu, H. Baicalin attenuates diet induced nonalcoholic steatohepatitis by inhibiting inflammation and oxidative stress via suppressing JNK signaling pathways. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 98, 111–117.

- Shi, L.; Hao, Z.; Zhang, S.; Wei, M.; Lu, B.; Wang, Z.; Ji, L. Baicalein and baicalin alleviate acetaminophen-induced liver injury by activating Nrf2 antioxidative pathway: The involvement of ERK1/2 and PKC. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018, 150, 9–23.

- Smolen, J.S.; Aletaha, D.; Barton, A.; Burmester, G.R.; Emery, P.; Firestein, G.S.; Kavanaugh, A.; McInnes, I.B.; Solomon, D.H.; Strand, V.; et al. Rheumatoid arthritis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2018, 4, 18001.

- Nemtsova, M.V.; Zaletaev, D.V.; Bure, I.V.; Mikhaylenko, D.S.; Kuznetsova, E.B.; Alekseeva, E.A.; Beloukhova, M.I.; Deviatkin, A.A.; Lukashev, A.N.; Zamyatnin, A.J. Epigenetic changes in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 570.

- Chung, I.-M.; Ketharnathan, S.; Thiruvengadam, M.; Rajakumar, G. Rheumatoid Arthritis: The Stride from Research to Clinical Practice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 900.

- Aletaha, D.; Smolen, J.S. Diagnosis and management of rheumatoid arthritis: A review. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2018, 320, 1360–1372.

- Yang, J.; Sundrud, M.S.; Skepner, J.; Yamagata, T. Targeting Th17 cells in autoimmune diseases. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 35, 493–500.

- Ikeuchi, T.; Moutsopoulos, N.M. Osteoimmunology in periodontitis; a paradigm for Th17/IL-17 inflammatory bone loss. Bone 2022, 163, 116500.

- Selimov, P.; Karalilova, R.; Damjanovska, L.; Delcheva, G.; Stankova, T.; Stefanova, K.; Maneva, A.; Selimov, T.; Batalov, A. Rheumatoid arthritis and the proinflammatory cytokine IL-17. Folia Med. 2023, 65, 53–59.

- Schett, G.; Rahman, P.; Ritchlin, C.; McInnes, I.B.; Elewaut, D.; Scher, J.U. Psoriatic arthritis from a mechanistic perspective. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2022, 18, 311–325.

- Agarwal, S.; Misra, R.; Aggarwal, A. Interleukin 17 levels are increased in juvenile idiopathic arthritis synovial fluid and induce synovial fibroblasts to produce proinflammatory cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases. J. Rheumatol. 2008, 35, 515–519.

- Kim, K.-W.; Cho, M.-L.; Park, M.-K.; Yoon, C.-H.; Park, S.-H.; Lee, S.-H.; Kim, H.-Y. Increased interleukin-17 production via a phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt and nuclear factor κB-dependent pathway in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2005, 7, R139–R148.

- Amatya, N.; Garg, A.V.; Gaffen, S.L. IL-17 Signaling: The Yin and the Yang. Trends Immunol. 2017, 38, 310–322.

- Yang, X.; Yang, J.; Zou, H. Baicalin inhibits IL-17-mediated joint inflammation in murine adjuvant-induced arthritis. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2013, 2013, 268065.

- Yang, J.; Yang, X.; Chu, Y.; Li, M. Identification of baicalin as an immunoregulatory compound by controlling TH17 cell differentiation. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17164.

- Tong, W.W.; Zhang, C.; Hong, T.; Liu, D.H.; Wang, C.; Li, J.; He, X.K.; Xu, W.D. Silibinin alleviates inflammation and induces apoptosis in human rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocytes and has a therapeutic effect on arthritis in rats. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3241.

- Rohm, T.V.; Meier, D.T.; Olefsky, J.M.; Donath, M.Y. Inflammation in obesity, diabetes, and related disorders. Immunity 2022, 55, 31–55.

- Olefsky, J.M.; Glass, C.K. Macrophages, inflammation, and insulin resistance. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2010, 72, 219–246.

- Xu, H.; Barnes, G.T.; Yang, Q.; Tan, G.; Yang, D.; Chou, C.J.; Sole, J.; Nichols, A.; Ross, J.S.; Tartaglia, L.A.; et al. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 112, 1821–1830.

- Suganami, T.; Tanimoto-Koyama, K.; Nishida, J.; Itoh, M.; Yuan, X.; Mizuarai, S.; Kotani, H.; Yamaoka, S.; Miyake, K.; Aoe, S.; et al. Role of the toll-like receptor 4/NF-κB pathway in saturated fatty acid–induced inflammatory changes in the interaction between adipocytes and macrophages. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007, 27, 84–91.

- Legaki, A.-I.; Moustakas, I.I.; Sikorska, M.; Papadopoulos, G.; Velliou, R.-I.; Chatzigeorgiou, A. Hepatocyte mitochondrial dynamics and bioenergetics in obesity-related non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2022, 11, 126–143.

- Li, M.; Chi, X.; Wang, Y.; Setrerrahmane, S.; Xie, W.; Xu, H. Trends in insulin resistance: Insights into mechanisms and therapeutic strategy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 216.

- Gao, D.; Jiao, J.; Wang, Z.; Huang, X.; Ni, X.; Fang, S.; Zhou, Q.; Zhu, X.; Sun, L.; Yang, Z.; et al. The roles of cell-cell and organ-organ crosstalk in the type 2 diabetes mellitus associated inflammatory microenvironment. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2022, 66, 15–25.

- Yingrui, W.; Zheng, L.; Guoyan, L.; Hongjie, W. Research progress of active ingredients of Scutellaria baicalensis in the treatment of type 2 diabetes and its complications. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 148, 112690.

- Ma, L.; Wu, F.; Shao, Q.; Chen, G.; Xu, L.; Lu, F. Baicalin alleviates oxidative stress and inflammation in diabetic nephropathy via Nrf2 and MAPK signaling pathway. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2021, 15, 3207–3221.

- Margaritopoulos, G.A.; Romagnoli, M.; Poletti, V.; Siafakas, N.M.; Wells, A.U.; Antoniou, K.M. Recent advances in the pathogenesis and clinical evaluation of pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2012, 21, 48–56.

- Castillo, J.R.; Peters, S.P.; Busse, W.W. Asthma exacerbations: Pathogenesis, Prevention, and Treatment. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pr. 2017, 5, 918–927.

- Mei, Q.; Liu, Z.; Zuo, H.; Yang, Z.; Qu, J. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: An update on pathogenesis. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 797292.

- Liu, G.; Friggeri, A.; Yang, Y.; Milosevic, J.; Ding, Q.; Thannickal, V.J.; Kaminski, N.; Abraham, E. miR-21 mediates fibrogenic activation of pulmonary fibroblasts and lung fibrosis. J. Exp. Med. 2010, 207, 1589–1597.

- Broekelmann, T.J.; Limper, A.H.; Colby, T.V.; McDonald, J.A. Transforming growth factor beta 1 is present at sites of extracellular matrix gene expression in human pulmonary fibrosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 6642–6646.

- Huang, X.; He, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, P.; Gui, D.; Cai, H.; Chen, A.; Chen, M.; Dai, C.; Yao, D.; et al. Baicalin attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis via adenosine A2a receptor related TGF-β1-induced ERK1/2 signaling pathway. BMC Pulm. Med. 2016, 16, 132.

- Scheibner, K.A.; Boodoo, S.; Collins, S.; Black, K.E.; Chan-Li, Y.; Zarek, P.; Powell, J.D.; Horton, M.R. The adenosine a2a receptor inhibits matrix-induced inflammation in a novel fashion. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2009, 40, 251–259.

- Shen, Y.; Goncharov, D.A.; Pena, A.; Baust, J.; Chavez, B.A.; Ray, A.; Rode, A.; Bachman, T.N.; Chang, B.; Jiang, L.; et al. Cross-talk between TSC2 and the extracellular matrix controls pulmonary vascular proliferation and pulmonary hypertension. Sci. Signal. 2022, 15, n2743.

- Yan, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, P.; Chen, A.; Chen, M.; Yao, D.; Xu, X.; Wang, L.; Huang, X. Baicalin attenuates hypoxia-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension to improve hypoxic cor pulmonale by reducing the activity of the p38 MAPK signaling pathway and MMP-9. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 2016, 2546402.

- Flynn, S.; Eisenstein, S. Inflammatory bowel disease presentation and diagnosis. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 99, 1051–1062.

- Rizzo, V.; Ferlazzo, N.; Currò, M.; Isola, G.; Matarese, M.; Bertuccio, M.P.; Caccamo, D.; Matarese, G.; Ientile, R. Baicalin-induced autophagy preserved LPS-stimulated intestinal cells from inflammation and alterations of paracellular permeability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2315.

- Neurath, M.F.; Leppkes, M. Resolution of ulcerative colitis. Semin. Immunopathol. 2019, 41, 747–756.

- Ungaro, R.; Mehandru, S.; Allen, P.B.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Colombel, J.-F. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet 2017, 389, 1756–1770.

- Wang, X.; Xie, L.; Long, J.; Liu, K.; Lu, J.; Liang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Dai, X.; Li, X. Therapeutic effect of baicalin on inflammatory bowel disease: A review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 283, 114749.

- Sun, X.; Pisano, M.; Xu, L.; Sun, F.; Xu, J.; Zheng, W.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, R.; Cui, X. Baicalin regulates autophagy to interfere with small intestinal acute graft-versus-host disease. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6551.

- Shen, J.; Cheng, J.; Zhu, S.; Zhao, J.; Ye, Q.; Xu, Y.; Dong, H.; Zheng, X. Regulating effect of baicalin on IKK/IKB/NF-kB signaling pathway and apoptosis-related proteins in rats with ulcerative colitis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 73, 193–200.

- Cui, L.; Feng, L.; Zhang, Z.H.; Bin Jia, X. The anti-inflammation effect of baicalin on experimental colitis through inhibiting TLR4/NF-κB pathway activation. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2014, 23, 294–303.

- Liang, S.; Deng, X.; Lei, L.; Zheng, Y.; Ai, J.; Chen, L.; Xiong, H.; Mei, Z.; Cheng, Y.-C.; Ren, Y. The comparative study of the therapeutic effects and mechanism of baicalin, baicalein, and their combination on ulcerative colitis rat. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1466.

- Zhang, C.L.; Zhang, S.; He, W.X.; Lu, J.L.; Xu, Y.J.; Yang, J.Y.; Liu, D. Baicalin may alleviate inflammatory infiltration in dextran sodium sulfate-induced chronic ulcerative colitis via inhibiting IL-33 expression. Life Sci. 2017, 186, 125–132.

- Feng, J.; Guo, C.; Zhu, Y.; Pang, L.; Yang, Z.; Zou, Y.; Zheng, X. Baicalin down regulates the expression of TLR4 and NFkB-p65 in colon tissue in mice with colitis induced by dextran sulfate sodium. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2014, 7, 4063–4072.

- Dai, S.-X.; Zou, Y.; Feng, Y.-L.; Liu, H.-B.; Zheng, X.-B. Baicalin down-regulates the expression of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) effectively for rats with ulcerative colitis. Phytother. Res. 2012, 26, 498–504.

- Lv, L.; Chen, Z.; Bai, W.; Hao, J.; Heng, Z.; Meng, C.; Wang, L.; Luo, X.; Wang, X.; Cao, Y.; et al. Taurohyodeoxycholic acid alleviates trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid induced ulcerative colitis via regulating Th1/Th2 and Th17/Treg cells balance. Life Sci. 2023, 318, 121501.

- Zhu, L.; Xu, L.-Z.; Zhao, S.; Shen, Z.-F.; Shen, H.; Zhan, L.-B. Protective effect of baicalin on the regulation of Treg/Th17 balance, gut microbiota and short-chain fatty acids in rats with ulcerative colitis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 5449–5460.

- Zou, Y.; Dai, S.-X.; Chi, H.-G.; Li, T.; He, Z.-W.; Wang, J.; Ye, C.-G.; Huang, G.-L.; Zhao, B.; Li, W.-Y.; et al. Baicalin attenuates TNBS-induced colitis in rats by modulating the Th17/Treg paradigm. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2015, 38, 1873–1887.

- Yu, F.-Y.; Huang, S.-G.; Zhang, H.-Y.; Ye, H.; Chi, H.-G.; Zou, Y.; Lv, R.-X.; Zheng, X.-B. Effects of baicalin in CD4 + CD29 + T cell subsets of ulcerative colitis patients. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 15299–15309.

- Goswami, S.K.; Ranjan, P.; Dutta, R.K.; Verma, S.K. Management of inflammation in cardiovascular diseases. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 173, 105912.

- Ginsberg, H.N.; Packard, C.J.; Chapman, M.J.; Borén, J.; Aguilar-Salinas, C.A.; Averna, M.; Ference, B.A.; Gaudet, D.; Hegele, R.A.; Kersten, S.; et al. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and their remnants: Metabolic insights, role in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and emerging therapeutic strategies—A consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society. Eur. Hear. J. 2021, 42, 4791–4806.

- Wolf, D.; Ley, K. Immunity and inflammation in atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 315–327.

- Nègre-Salvayre, A.; Augé, N.; Camaré, C.; Bacchetti, T.; Ferretti, G.; Salvayre, R. Dual signaling evoked by oxidized LDLs in vascular cells. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 106, 118–133.

- Zhou, Y.; Mao, S.; Zhou, M. Effect of the flavonoid baicalein as a feed additive on the growth performance, immunity, and antioxidant capacity of broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 2790–2799.

- Liao, P.; Liu, L.; Wang, B.; Li, W.; Fang, X.; Guan, S. Baicalin and geniposide attenuate atherosclerosis involving lipids regulation and immunoregulation in ApoE-/-mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 740, 488–495.

- Huang, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Jiang, X.; Li, Z. The mechanism of efferocytosis in the pathogenesis of periodontitis and its possible therapeutic strategies. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2023, 113, 365–375.

- Kutuk, O.; Basaga, H. Inflammation meets oxidation: NF-κB as a mediator of initial lesion development in atherosclerosis. Trends Mol. Med. 2003, 9, 549–557.

- Wang, D.; Tan, Z.; Yang, J.; Li, L.; Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, Q.; et al. Perfluorooctane sulfonate promotes atherosclerosis by modulating M1 polarization of macrophages through the NF-κB pathway. Ecotox. Environ. Safe 2023, 249, 114384.

- Wang, B.; Liao, P.P.; Liu, L.H.; Fang, X.; Li, W.; Guan, S.M. Baicalin and geniposide inhibit the development of atherosclerosis by increasing Wnt1 and inhibiting dickkopf-related protein-1 expression. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2016, 13, 846–854.

- Zhang, S.; Gang, X.; Yang, S.; Cui, M.; Sun, L.; Li, Z.; Wang, G. The alterations in and the role of the Th17/Treg balance in metabolic diseases. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 678355.

- Potekhina, A.V.; Pylaeva, E.; Provatorov, S.; Ruleva, N.; Masenko, V.; Noeva, E.; Krasnikova, T.; Arefieva, T. Treg/Th17 balance in stable CAD patients with different stages of coronary atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2015, 238, 17–21.

- Jiang, X.; Liu, L.; Sun, J.; Yang, J.; Xiang, D.; Yang, Y.; Li, M.; Li, Z.; Gao, L.; Xie, R. Baicalin inhibits IgG production by regulating Treg/Th17 axis in a mouse model of red blood cell transfusion. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 66, 282–287.

- Yang, J.; Yang, X.; Li, M. Baicalin, a natural compound, promotes regulatory T cell differentiation. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 12, 64.

- Wu, D.; Ding, L.; Tang, X.; Wang, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, T. Baicalin protects against hypertension-associated intestinal barrier impairment in part through enhanced microbial production of short-chain fatty acids. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1271.

- Ding, L.; Jia, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhu, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, T. Baicalin relaxes vascular smooth muscle and lowers blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 111, 325–330.

More

Information

Subjects:

Veterinary Sciences

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

934

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

05 Jun 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No