| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Luis Jimenez-Cabello | -- | 3654 | 2023-05-22 10:49:49 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | -5 word(s) | 3649 | 2023-05-23 02:45:58 | | |

Video Upload Options

Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease (EHD) of ruminants is a viral pathology that has significant welfare, social, and economic implications. The causative agent, epizootic hemorrhagic disease virus (EHDV), belongs to the Orbivirus genus and leads to significant regional disease outbreaks among livestock and wildlife in North America, Asia, Africa, and Oceania, causing significant morbidity and mortality.

1. Introduction

2. EHDV, the Etiological Agent of EHD

3. Changes in EHDV Epidemiology

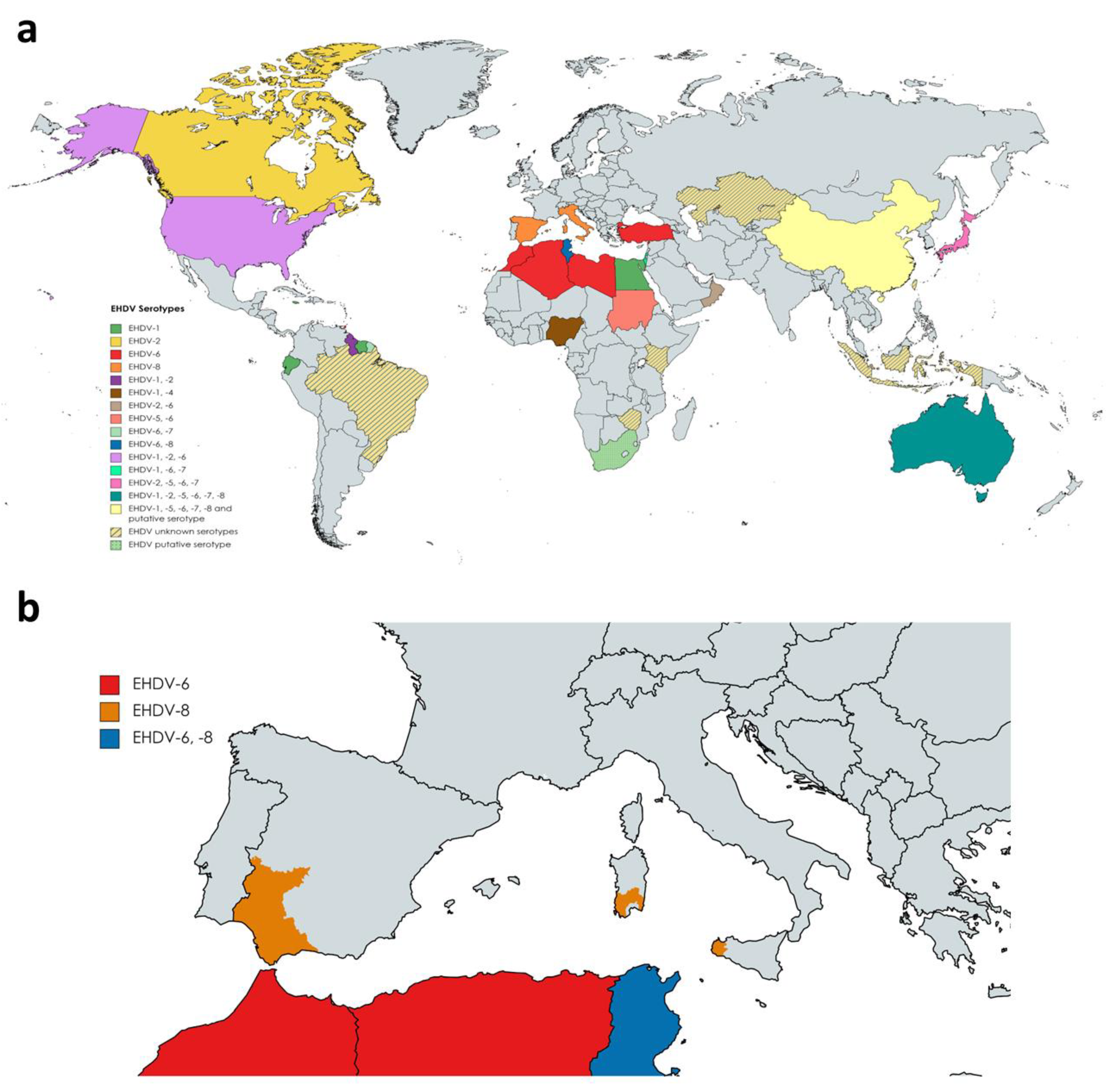

To date, seven serotypes of EHDV have been identified, named as 1–2 and 4–8, designated based on extensive phylogenetic studies, sequencing data, and cross-neutralization assays [10]. Genetic analyses demonstrated that previously identified serotype 3 [32] (Nigerian strain Ib Ar 22619) was serotype 1 [10]. EHDV has been isolated in North and South America, Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and Oceania (Figure 2a). To date, it is endemic in parts of North America, Australia, and certain countries of Asia and Africa [33]. EHDV was first detected in the USA in 1955 when WTD were severely affected showing high mortality [34]. Among the seven serotypes proposed, EHDV-1, 2, and 6 have been reported to be present in North America, where WTD is the most severely affected host and the scale of individual outbreaks increased with time [35][36][37]. In Australia, six out of seven serotypes (EHDV-1, -2, -5, -6, -7, and -8) have been detected over the years [33][38]. Globally, the presence of EHDV has been noted in Japan (serotypes 2 and 7, and serotypes 5 and 6 recently isolated from Culicoides insect vectors), China (serotypes 1, 5, 6, 7, 8), Morocco (serotype 6), Algeria (serotype 6), Libya (serotype 6), Turkey (serotype 6), Tunisia (serotypes 6 and 8), Egypt (serotype 1), Oman (serotype 2 and 6), Sudan (serotype 5 and 6), Nigeria (serotypes 1 and 4), the island of Mayotte (serotype 6), French Guiana (serotypes 6 and 7), Ecuador (serotype 1), Trinidad (serotype 6) and Israel (serotypes 1, 6 and 7) [39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57]. Genome detection or serological evidences also indicate the presence of EHDV (unknown serotypes) in Indonesia, Taiwan, Zimbabwe, Kenya, Kazakhstan, and Brazil [58][59][60][61][62]. Nucleotide sequencing and neutralization tests suggest novel strains of EHDV identified in South Africa and China as new putative serotypes [63][64].

Outbreaks during 2020 in Turkey and North Africa were originated by serotype 6, while serotype 8 was the causative virus of several outbreaks in cattle in Tunisia during 2021 [48]. This was the first evidence of EHDV-8 circulation since 1982, when this serotype was isolated in Australia. In Europe, there was no evidence of the presence of EHDV. However, it emerged on the continent for the first time in October 2022. After BTV-like clinical signs were noticed in some animals, EHDV was identified as the causative agent of cattle disease outbreaks in Sicily and southwestern Sardinia (Figure 2b). Subsequently, it was confirmed that these outbreaks were caused by EHDV-8, an identical strain to the one circulating in Tunisia between 2021 and 2022, pointing to North Africa as the direct origin [65]. Consecutively, EHDV outbreaks were detected in southern Spain, with EHDV serotype 8 confirmed and notified to the WOAH as the causative agent (Figure 2b).

4. Disease and Pathology

5. Experimental Animal Models of EHDV

5.1. White-Tailed Deer (WTD) and Other Cervid Species

5.2. Cattle and Other Farm Animals

5.3. Mouse Models

6. Classic and Novel Vaccine Approaches against EHDV

7. Conclusions

References

- Huismans, H.; Bremer, C.W.; Barber, T.L. The Nucleic Acid and Proteins of Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease Virus. Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 1979, 46, 95–104.

- Stewart, M.; Hardy, A.; Barry, G.; Pinto, R.M.; Caporale, M.; Melzi, E.; Hughes, J.; Taggart, A.; Janowicz, A.; Varela, M.; et al. Characterization of a Second Open Reading Frame in Genome Segment 10 of Bluetongue Virus. J. Gen. Virol. 2015, 96, 3280–3293.

- Belhouchet, M.; Mohd Jaafar, F.; Firth, A.E.; Grimes, J.M.; Mertens, P.P.C.; Attoui, H. Detection of a Fourth Orbivirus Non-Structural Protein. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e25697.

- Mecham, J.O.; Dean, V.C. Protein Coding Assignment for the Genome of Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease Virus. J. Gen. Virol. 1988, 69 Pt 6, 1255–1262.

- Zhang, X.; Boyce, M.; Bhattacharya, B.; Zhang, X.; Schein, S.; Roy, P.; Zhou, Z.H. Bluetongue Virus Coat Protein VP2 Contains Sialic Acid-Binding Domains, and VP5 Resembles Enveloped Virus Fusion Proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 6292–6297.

- Urakawa, T.; Ritter, D.G.; Roy, P. Expression of Largest RNA Segment and Synthesis of VP1 Protein of Bluetongue Virus in Insect Cells by Recombinant Baculovirus: Association of VP1 Protein with RNA Polymerase Activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989, 17, 7395–7401.

- Stäuber, N.; Martinez-Costas, J.; Sutton, G.; Monastyrskaya, K.; Roy, P. Bluetongue Virus VP6 Protein Binds ATP and Exhibits an RNA-Dependent ATPase Function and a Helicase Activity That Catalyze the Unwinding of Double-Stranded RNA Substrates. J. Virol. 1997, 71, 7220–7226.

- Sutton, G.; Grimes, J.M.; Stuart, D.I.; Roy, P. Bluetongue Virus VP4 Is an RNA-Capping Assembly Line. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007, 14, 449–451.

- Wu, W.; Roy, P. Sialic Acid Binding Sites in VP2 of Bluetongue Virus and Their Use during Virus Entry. J. Virol. 2022, 96, e0167721.

- Anthony, S.J.; Maan, S.; Maan, N.; Kgosana, L.; Bachanek-Bankowska, K.; Batten, C.; Darpel, K.E.; Sutton, G.; Attoui, H.; Mertens, P.P.C. Genetic and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Outer-Coat Proteins VP2 and VP5 of Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease Virus (EHDV): Comparison of Genetic and Serological Data to Characterise the EHDV Serogroup. Virus Res. 2009, 145, 200–210.

- Forzan, M.; Marsh, M.; Roy, P. Bluetongue Virus Entry into Cells. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 4819–4827.

- Maan, N.S.; Maan, S.; Potgieter, A.C.; Wright, I.M.; Belaganahalli, M.; Mertens, P.P.C. Development of Real-Time RT-PCR Assays for Detection and Typing of Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease Virus. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2017, 64, 1120–1132.

- Sun, F.; Cochran, M.; Beckham, T.; Clavijo, A. Molecular Typing of Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus Serotypes by One-Step Multiplex RT-PCR. J. Wildl. Dis. 2014, 50, 639–644.

- Anthony, S.J.; Maan, N.; Maan, S.; Sutton, G.; Attoui, H.; Mertens, P.P.C. Genetic and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Core Proteins VP1, VP3, VP4, VP6 and VP7 of Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease Virus (EHDV). Virus Res. 2009, 145, 187–199.

- Mecham, J.O.; Stallknecht, D.; Wilson, W.C. The S7 Gene and VP7 Protein Are Highly Conserved among Temporally and Geographically Distinct American Isolates of Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus. Virus Res. 2003, 94, 129–133.

- Bréard, E.; Viarouge, C.; Donnet, F.; Sailleau, C.; Rossi, S.; Pourquier, P.; Vitour, D.; Comtet, L.; Zientara, S. Evaluation of a Commercial ELISA for Detection of Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease Antibodies in Domestic and Wild Ruminant Sera. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2020, 67, 2475–2481.

- Forzan, M.; Pizzurro, F.; Zaccaria, G.; Mazzei, M.; Spedicato, M.; Carmine, I.; Salini, R.; Tolari, F.; Cerri, D.; Savini, G.; et al. Competitive Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay Using Baculovirus-Expressed VP7 for Detection of Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease Virus (EHDV) Antibodies. J. Virol. Methods 2017, 248, 212–216.

- Serroni, A.; Ulisse, S.; Iorio, M.; Laguardia, C.; Testa, L.; Armillotta, G.; Caporale, M.; Salini, R.; Lelli, D.; Wernery, U.; et al. Development of a Competitive Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay Based on Purified Recombinant Viral Protein 7 for Serological Diagnosis of Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease in Camels. J. Trop. Med. 2022, 2022, 5210771.

- Kusari, J.; Roy, P. Molecular and Genetic Comparisons of Two Serotypes of Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease of Deer Virus. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1986, 47, 1713–1717.

- Nel, L.H.; Picard, L.A.; Huismans, H. A Characterization of the Nonstructural Protein from Which the Virus-Specified Tubules in Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease Virus-Infected Cells Are Composed. Virus Res. 1991, 18, 219–230.

- Owens, R.J.; Limn, C.; Roy, P. Role of an Arbovirus Nonstructural Protein in Cellular Pathogenesis and Virus Release. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 6649–6656.

- Boyce, M.; Celma, C.C.P.; Roy, P. Bluetongue Virus Non-Structural Protein 1 Is a Positive Regulator of Viral Protein Synthesis. Virol. J. 2012, 9, 178.

- Anthony, S.J.; Maan, N.; Maan, S.; Sutton, G.; Attoui, H.; Mertens, P.P.C. Genetic and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Non-Structural Proteins NS1, NS2 and NS3 of Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease Virus (EHDV). Virus Res. 2009, 145, 211–219.

- Theron, J.; Huismans, H.; Nel, L.H. Identification of a Short Domain within the Non-Structural Protein NS2 of Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease Virus That Is Important for Single Strand RNA-Binding Activity. J. Gen. Virol. 1996, 77, 129–137.

- Uitenweerde, J.M.; Theron, J.; Stoltz, M.A.; Huismans, H. The Multimeric Nonstructural NS2 Proteins of Bluetongue Virus, African Horsesickness Virus, and Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus Differ in Their Single-Stranded RNA-Binding Ability. Virology 1995, 209, 624–632.

- Theron, J.; Huismans, H.; Nel, L.H. Site-Specific Mutations in the NS2 Protein of Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease Virus Markedly Affect the Formation of Cytoplasmic Inclusion Bodies. Arch. Virol. 1996, 141, 1143–1151.

- Jensen, M.J.; Wilson, W.C. A Model for the Membrane Topology of the NS3 Protein as Predicted from the Sequence of Segment 10 of Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease Virus Serotype 1. Arch. Virol. 1995, 140, 799–805.

- Hyatt, A.D.; Zhao, Y.; Roy, P. Release of Bluetongue Virus-like Particles from Insect Cells Is Mediated by BTV Nonstructural Protein NS3/NS3A. Virology 1993, 193, 592–603.

- Jensen, M.J.; Cheney, I.W.; Thompson, L.H.; Mecham, J.O.; Wilson, W.C.; Yamakawa, M.; Roy, P.; Gorman, B.M. The Smallest Gene of the Orbivirus, Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease, Is Expressed in Virus-Infected Cells as Two Proteins and the Expression Differs from That of the Cognate Gene of Bluetongue Virus. Virus Res. 1994, 32, 353–364.

- Fablet, A.; Kundlacz, C.; Dupré, J.; Hirchaud, E.; Postic, L.; Sailleau, C.; Bréard, E.; Zientara, S.; Vitour, D.; Caignard, G. Comparative Virus-Host Protein Interactions of the Bluetongue Virus NS4 Virulence Factor. Viruses 2022, 14, 182.

- Ratinier, M.; Shaw, A.E.; Barry, G.; Gu, Q.; Di Gialleonardo, L.; Janowicz, A.; Varela, M.; Randall, R.E.; Caporale, M.; Palmarini, M. Bluetongue Virus NS4 Protein Is an Interferon Antagonist and a Determinant of Virus Virulence. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 5427–5439.

- Campbell, C.H.; George, T.D.S. A Preliminary Report of a Comparison of Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease Viruses from Australia with Others from North America, Japan and Nigeria. Aust. Vet. J. 1986, 63, 233.

- Noronha, L.E.; Cohnstaedt, L.W.; Richt, J.A.; Wilson, W.C. Perspectives on the Changing Landscape of Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus Control. Viruses 2021, 13, 2268.

- Shope, R.E.; Lester, G.M.; Robert, M. Deer Mortality—Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease of Deer. N. J. Outdoors 1955, 6, 17–21.

- Ruder, M.G.; Lysyk, T.J.; Stallknecht, D.E.; Foil, L.D.; Johnson, D.J.; Chase, C.C.; Dargatz, D.A.; Gibbs, E.P.J. Transmission and Epidemiology of Bluetongue and Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease in North America: Current Perspectives, Research Gaps, and Future Directions. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2015, 15, 348–363.

- Ruder, M.G.; Johnson, D.; Ostlund, E.; Allison, A.B.; Kienzle, C.; Phillips, J.E.; Poulson, R.L.; Stallknecht, D.E. The First 10 Years (2006-15) of Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus Serotype 6 in the USA. J. Wildl. Dis. 2017, 53, 901–905.

- Schirtzinger, E.E.; Jasperson, D.C.; Ruder, M.G.; Stallknecht, D.E.; Chase, C.C.L.; Johnson, D.J.; Ostlund, E.N.; Wilson, W.C. Evaluation of 2012 US EHDV-2 Outbreak Isolates for Genetic Determinants of Cattle Infection. J. Gen. Virol. 2019, 100, 556–567.

- Weir, R.P.; Harmsen, M.B.; Hunt, N.T.; Blacksell, S.D.; Lunt, R.A.; Pritchard, L.I.; Newberry, K.M.; Hyatt, A.D.; Gould, A.R.; Melville, L.F. EHDV-1, a New Australian Serotype of Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease Virus Isolated from Sentinel Cattle in the Northern Territory. Vet. Microbiol. 1997, 58, 135–143.

- Ahmed, S.; Mahmoud, M.A.E.-F.; Viarouge, C.; Sailleau, C.; Zientara, S.; Breard, E. Presence of Bluetongue and Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Viruses in Egypt in 2016 and 2017. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2019, 73, 221–226.

- Viarouge, C.; Lancelot, R.; Rives, G.; Bréard, E.; Miller, M.; Baudrimont, X.; Doceul, V.; Vitour, D.; Zientara, S.; Sailleau, C. Identification of Bluetongue Virus and Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus Serotypes in French Guiana in 2011 and 2012. Vet. Microbiol. 2014, 174, 78–85.

- Qi, Y.; Wang, F.; Chang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Li, H.; Yu, L. Identification and Complete-Genome Phylogenetic Analysis of an Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus Serotype 7 Strain Isolated in China. Arch. Virol. 2019, 164, 3121–3126.

- Yadin, H.; Brenner, J.; Bumbrov, V.; Oved, Z.; Stram, Y.; Klement, E.; Perl, S.; Anthony, S.; Maan, S.; Batten, C.; et al. Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease Virus Type 7 Infection in Cattle in Israel. Vet. Rec. 2008, 162, 53–56.

- Temizel, E.M.; Yesilbag, K.; Batten, C.; Senturk, S.; Maan, N.S.; Mertens, P.P.C.; Batmaz, H. Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease in Cattle, Western Turkey. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009, 15, 317–319.

- Verdezoto, J.; Breard, E.; Viarouge, C.; Quenault, H.; Lucas, P.; Sailleau, C.; Zientara, S.; Augot, D.; Zapata, S. Novel Serotype of Bluetongue Virus in South America and First Report of Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease Virus in Ecuador. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2018, 65, 244–247.

- Rajko-Nenow, P.; Brown-Joseph, T.; Tennakoon, C.; Flannery, J.; Oura, C.A.L.; Batten, C. Detection of a Novel Reassortant Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus Serotype 6 in Cattle in Trinidad, West Indies, Containing Nine RNA Segments Derived from Exotic EHDV Strains with an Australian Origin. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2019, 74, 103931.

- Mohammed, M.E.; Aradaib, I.E.; Mukhtar, M.M.; Ghalib, H.W.; Riemann, H.P.; Oyejide, A.; Osburn, B.I. Application of Molecular Biological Techniques for Detection of Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus (EHDV-318) Recovered from a Sentinel Calf in Central Sudan. Vet. Microbiol. 1996, 52, 201–208.

- Aradaib, I.E.; Mohammed, M.E.; Mukhtar, M.M.; Ghalib, H.W.; Osburn, B.I. Serogrouping and Topotyping of Sudanese and United States Strains of Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus Using PCR. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1997, 20, 211–218.

- Sghaier, S.; Sailleau, C.; Marcacci, M.; Thabet, S.; Curini, V.; Ben Hassine, T.; Teodori, L.; Portanti, O.; Hammami, S.; Jurisic, L.; et al. Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease Virus Serotype 8 in Tunisia, 2021. Viruses 2022, 15, 16.

- Duan, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhu, P.; Xiao, L.; Li, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, L.; Zhu, J. A Serologic Investigation of Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus in China between 2014 and 2019. Virol. Sin. 2022, 37, 513–520.

- Mejri, S.; Dhaou, S.B.; Jemli, M.; Bréard, E.; Sailleau, C.; Sghaier, S.; Zouari, M.; Lorusso, A.; Savini, G.; Zientara, S.; et al. Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease Virus Circulation in Tunisia. Vet. Ital. 2018, 54, 87–90.

- Yamamoto, K.; Hiromatsu, R.; Kaida, M.; Kato, T.; Yanase, T.; Shirafuji, H. Isolation of Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus Serotype 7 from Cattle Showing Fever in Japan in 2016 and Improvement of a Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction Assay to Detect Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2021, 83, 1378–1388.

- Mahmoud, A.; Danzetta, M.L.; di Sabatino, D.; Spedicato, M.; Alkhatal, Z.; Dayhum, A.; Tolari, F.; Forzan, M.; Mazzei, M.; Savini, G. First Seroprevalence Investigation of Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease Virus in Libya. Open Vet. J. 2021, 11, 301–308.

- Brown-Joseph, T.; Rajko-Nenow, P.; Hicks, H.; Sahadeo, N.; Harrup, L.E.; Carrington, C.V.; Batten, C.; Oura, C.A.L. Identification and Characterization of Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus Serotype 6 in Cattle Co-Infected with Bluetongue Virus in Trinidad, West Indies. Vet. Microbiol. 2019, 229, 1–6.

- Dommergues, L.; Viarouge, C.; Métras, R.; Youssouffi, C.; Sailleau, C.; Zientara, S.; Cardinale, E.; Cêtre-Sossah, C. Evidence of Bluetongue and Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease Circulation on the Island of Mayotte. Acta Trop. 2019, 191, 24–28.

- Wilson, W.C.; Ruder, M.G.; Klement, E.; Jasperson, D.C.; Yadin, H.; Stallknecht, D.E.; Mead, D.G.; Howerth, E. Genetic Characterization of Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus Strains Isolated from Cattle in Israel. J. Gen. Virol. 2015, 96, 1400–1410.

- Murota, K.; Ishii, K.; Mekaru, Y.; Araki, M.; Suda, Y.; Shirafuji, H.; Kobayashi, D.; Isawa, H.; Yanase, T. Isolation of Culicoides- and Mosquito-Borne Orbiviruses in the Southwestern Islands of Japan between 2014 and 2019. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2021, 21, 796–808.

- Al-Busaidy, S.M.; Mellor, P.S. Epidemiology of Bluetongue and Related Orbiviruses in the Sultanate of Oman. Epidemiol. Infect. 1991, 106, 167–178.

- Gordon, S.J.G.; Bolwell, C.; Rogers, C.W.; Musuka, G.; Kelly, P.; Guthrie, A.; Mellor, P.S.; Hamblin, C. A Serosurvey of Bluetongue and Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease in a Convenience Sample of Sheep and Cattle Herds in Zimbabwe. Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 2017, 84, 1505.

- Toye, P.G.; Batten, C.A.; Kiara, H.; Henstock, M.R.; Edwards, L.; Thumbi, S.; Poole, E.J.; Handel, I.G.; Bronsvoort, B.M.d.C.; Hanotte, O.; et al. Bluetongue and Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease Virus in Local Breeds of Cattle in Kenya. Res. Vet. Sci. 2013, 94, 769–773.

- Lundervold, M.; Milner-Gulland, E.J.; O’Callaghan, C.J.; Hamblin, C.; Corteyn, A.; Macmillan, A.P. A Serological Survey of Ruminant Livestock in Kazakhstan during Post-Soviet Transitions in Farming and Disease Control. Acta Vet. Scand. 2004, 45, 211.

- Favero, C.M.; Matos, A.C.D.; Campos, F.S.; Cândido, M.V.; Costa, É.A.; Heinemann, M.B.; Barbosa-Stancioli, E.F.; Lobato, Z.I.P. Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease in Brocket Deer, Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013, 19, 346–348.

- Inaba, Y. Ibaraki Disease and Its Relationship to Bluetongue. Aust. Vet. J. 1975, 51, 178–185.

- Yang, H.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Yang, Z.; Liao, D.; Zhu, J.; Li, H. Novel Serotype of Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 3081–3083.

- Wright, I.M. Serological and Genetic Characterisation of Putative New Serotypes of Bluetongue Virus and Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease Virus Isolated from an Alpaca. Master’s Thesis, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa, 2014.

- Lorusso, A.; Cappai, S.; Loi, F.; Pinna, L.; Ruiu, A.; Puggioni, G.; Guercio, A.; Purpari, G.; Vicari, D.; Sghaier, S.; et al. First Detection of Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease Virus in the European Union, Italy-2022. bioRxiv 2022.

- Allison, A.B.; Goekjian, V.H.; Potgieter, A.C.; Wilson, W.C.; Johnson, D.J.; Mertens, P.P.C.; Stallknecht, D.E. Detection of a Novel Reassortant Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus (EHDV) in the USA Containing RNA Segments Derived from Both Exotic (EHDV-6) and Endemic (EHDV-2) Serotypes. J. Gen. Virol. 2010, 91, 430–439.

- Allison, A.B.; Holmes, E.C.; Potgieter, A.C.; Wright, I.M.; Sailleau, C.; Breard, E.; Ruder, M.G.; Stallknecht, D.E. Segmental Configuration and Putative Origin of the Reassortant Orbivirus, Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus Serotype 6, Strain Indiana. Virology 2012, 424, 67–75.

- Howerth, E.W.; Stallknecht, D.E.; Kirkland, P.D. Bluetongue, Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease, and Other Orbivirus-Related Diseases. In Infectious Diseases of Wild Mammals; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 77–97. ISBN 978-0-470-34488-0.

- Gaydos, J.K.; Davidson, W.R.; Elvinger, F.; Howerth, E.W.; Murphy, M.; Stallknecht, D.E. Cross-Protection between Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus Serotypes 1 and 2 in White-Tailed Deer. J. Wildl. Dis. 2002, 38, 720–728.

- Brodie, S.J.; Bardsley, K.D.; Diem, K.; Mecham, J.O.; Norelius, S.E.; Wilson, W.C. Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease: Analysis of Tissues by Amplification and in Situ Hybridization Reveals Widespread Orbivirus Infection at Low Copy Numbers. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 3863–3871.

- Noon, T.H.; Wesche, S.L.; Heffelfinger, J.; Fuller, A.; Bradley, G.A.; Reggiardo, C. Hemorrhagic Disease in Deer in Arizona. J. Wildl. Dis 2002, 38, 177–181.

- Roug, A.; Shannon, J.; Hersey, K.; Heaton, W.; van Wettere, A. Investigation into Causes of Antler Deformities in Mule Deer (Odocoileus hemionus) Bucks in Southern Utah, USA. J. Wildl. Dis. 2022, 58, 222–227.

- Raabis, S.M.; Byers, S.R.; Han, S.; Callan, R.J. Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease in a Yak. Can. Vet. J. 2014, 55, 369–372.

- Kedmi, M.; Levi, S.; Galon, N.; Bomborov, V.; Yadin, H.; Batten, C.; Klement, E. No Evidence for Involvement of Sheep in the Epidemiology of Cattle Virulent Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus. Vet. Microbiol. 2011, 148, 408–412.

- Nol, P.; Kato, C.; Reeves, W.K.; Rhyan, J.; Spraker, T.; Gidlewski, T.; VerCauteren, K.; Salman, M. Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Outbreak in a Captive Facility Housing White-Tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus), Bison (Bison bison), Elk (Cervus elaphus), Cattle (Bos taurus), and Goats (Capra hircus) in Colorado, U.S.A. J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2010, 41, 510–515.

- Mills, M.K.; Ruder, M.G.; Nayduch, D.; Michel, K.; Drolet, B.S. Dynamics of Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus Infection within the Vector, Culicoides Sonorensis (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae). PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188865.

- Darpel, K.E.; Langner, K.F.A.; Nimtz, M.; Anthony, S.J.; Brownlie, J.; Takamatsu, H.-H.; Mellor, P.S.; Mertens, P.P.C. Saliva Proteins of Vector Culicoides Modify Structure and Infectivity of Bluetongue Virus Particles. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17545.

- McLaughlin, B.E.; DeMaula, C.D.; Wilson, W.C.; Boyce, W.M.; MacLachlan, N.J. Replication of Bluetongue Virus and Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus in Pulmonary Artery Endothelial Cells Obtained from Cattle, Sheep, and Deer. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2003, 64, 860–865.

- Sharma, P.; Stallknecht, D.E.; Howerth, E.W. Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease Virus Induced Apoptosis in Bovine Carotid Artery Endothelium Is P53 Independent. Vet. Ital. 2016, 52, 363–368.

- Shai, B.; Schmukler, E.; Yaniv, R.; Ziv, N.; Horn, G.; Bumbarov, V.; Yadin, H.; Smorodinsky, N.I.; Bacharach, E.; Pinkas-Kramarski, R.; et al. Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus Induces and Benefits from Cell Stress, Autophagy, and Apoptosis. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 13397–13408.

- Sharma, P.; Stallknecht, D.E.; Murphy, M.D.; Howerth, E.W. Expression of Interleukin-1 Beta and Interleukin-6 in White-Tailed Deer Infected with Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus. Vet. Ital. 2015, 51, 283–288.

- Howerth, E.W. Cytokine Release and Endothelial Dysfunction: A Perfect Storm in Orbivirus Pathogenesis. Vet. Ital. 2015, 51, 275–281.

- Sánchez-Cordón, P.J.; Pedrera, M.; Risalde, M.A.; Molina, V.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, B.; Núñez, A.; Sánchez-Vizcaíno, J.M.; Gómez-Villamandos, J.C. Potential Role of Proinflammatory Cytokines in the Pathogenetic Mechanisms of Vascular Lesions in Goats Naturally Infected with Bluetongue Virus Serotype 1. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2013, 60, 252–262.

- Quist, C.F.; Howerth, E.W.; Stallknecht, D.E.; Brown, J.; Pisell, T.; Nettles, V.F. Host Defense Responses Associated with Experimental Hemorrhagic Disease in White-Tailed Deer. J. Wildl. Dis. 1997, 33, 584–599.

- Wessels, J.E.; Ishida, Y.; Rivera, N.A.; Stirewalt, S.L.; Brown, W.M.; Novakofski, J.E.; Roca, A.L.; Mateus-Pinilla, N.E. The Impact of Variation in the Toll-like Receptor 3 Gene on Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease in Illinois Wild White-Tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus). Genes 2023, 14, 426.

- Stallknecht, D.E.; Howerth, E.W.; Kellogg, M.L.; Quist, C.F.; Pisell, T. In Vitro Replication of Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease and Bluetongue Viruses in White-Tailed Deer Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells and Virus-Cell Association during in Vivo Infections. J. Wildl. Dis. 1997, 33, 574–583.

- Gibbs, E.P.J.; Lawman, M.J.P. Infection of British Deer and Farm Animals with Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease of Deer Virus. J. Comp. Pathol. 1977, 87, 335–343.

- Fletch, A.L.; Karstad, L.H. Studies on the Pathogenesis of Experimental Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease of White-Tailed Deer. Can. J. Comp. Med. 1971, 35, 224–229.

- Shope, R.E.; Macnamara, L.G.; Mangold, R. A virus-induced epizootic hemorrhagic disease of the virginia white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). J. Exp. Med. 1960, 111, 155–170.

- Ruder, M.G.; Stallknecht, D.E.; Allison, A.B.; Mead, D.G.; Carter, D.L.; Howerth, E.W. Host and Potential Vector Susceptibility to an Emerging Orbivirus in the United States: Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus Serotype 6. Vet. Pathol. 2016, 53, 574–584.

- Ruder, M.G.; Allison, A.B.; Stallknecht, D.E.; Mead, D.G.; McGraw, S.M.; Carter, D.L.; Kubiski, S.V.; Batten, C.A.; Klement, E.; Howerth, E.W. Susceptibility of White-Tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus) to Experimental Infection with Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus Serotype 7. J. Wildl. Dis. 2012, 48, 676–685.

- Gaydos, J.K.; Davidson, W.R.; Elvinger, F.; Mead, D.G.; Howerth, E.W.; Stallknecht, D.E. Innate Resistance to Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease in White-Tailed Deer. J. Wildl. Dis. 2002, 38, 713–719.

- Palmer, M.V.; Cox, R.J.; Waters, W.R.; Thacker, T.C.; Whipple, D.L. Using White-Tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus) in Infectious Disease Research. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2017, 56, 350–360.

- Aradaib, I.E.; Sawyer, M.M.; Osburn, B.I. Experimental Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus Infection in Calves: Virologic and Serologic Studies. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 1994, 6, 489–492.

- Bowen, R.A. Serologic Responses of Calves to Sequential Infections with Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus Serotypes. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1987, 48, 1449–1452.

- Marín-Lopez, A.; Calvo-Pinilla, E.; Moreno, S.; Utrilla-Trigo, S.; Nogales, A.; Brun, A.; Fikrig, E.; Ortego, J. Modeling Arboviral Infection in Mice Lacking the Interferon Alpha/Beta Receptor. Viruses 2019, 11, 35.

- Calvo-Pinilla, E.; Rodríguez-Calvo, T.; Anguita, J.; Sevilla, N.; Ortego, J. Establishment of a Bluetongue Virus Infection Model in Mice That Are Deficient in the Alpha/Beta Interferon Receptor. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5171.

- Marín-López, A.; Bermúdez, R.; Calvo-Pinilla, E.; Moreno, S.; Brun, A.; Ortego, J. Pathological Characterization of IFNAR(-/-) Mice Infected with Bluetongue Virus Serotype 4. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2016, 12, 1448–1460.

- Castillo-Olivares, J.; Calvo-Pinilla, E.; Casanova, I.; Bachanek-Bankowska, K.; Chiam, R.; Maan, S.; Nieto, J.M.; Ortego, J.; Mertens, P.P.C. A Modified Vaccinia Ankara Virus (MVA) Vaccine Expressing African Horse Sickness Virus (AHSV) VP2 Protects against AHSV Challenge in an IFNAR−/− Mouse Model. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16503.

- McVey, D.S.; MacLachlan, N.J. Vaccines for Prevention of Bluetongue and Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease in Livestock: A North American Perspective. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2015, 15, 385–396.

- van Rijn, P.A. Prospects of Next-Generation Vaccines for Bluetongue. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 407.

- Sunwoo, S.Y.; Noronha, L.E.; Morozov, I.; Trujillo, J.D.; Kim, I.J.; Schirtzinger, E.E.; Faburay, B.; Drolet, B.S.; Urbaniak, K.; McVey, D.S.; et al. Evaluation of A Baculovirus-Expressed VP2 Subunit Vaccine for the Protection of White-Tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus) from Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease. Vaccines 2020, 8, 59.

- Jiménez-Cabello, L.; Utrilla-Trigo, S.; Calvo-Pinilla, E.; Moreno, S.; Nogales, A.; Ortego, J.; Marín-López, A. Viral Vector Vaccines against Bluetongue Virus. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 42.

- Jiménez-Cabello, L.; Utrilla-Trigo, S.; Barreiro-Piñeiro, N.; Pose-Boirazian, T.; Martínez-Costas, J.; Marín-López, A.; Ortego, J. Nanoparticle- and Microparticle-Based Vaccines against Orbiviruses of Veterinary Importance. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1124.