| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Meng Zhang | -- | 5607 | 2023-02-16 15:41:19 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | + 98 word(s) | 5705 | 2023-02-17 01:24:26 | | |

Video Upload Options

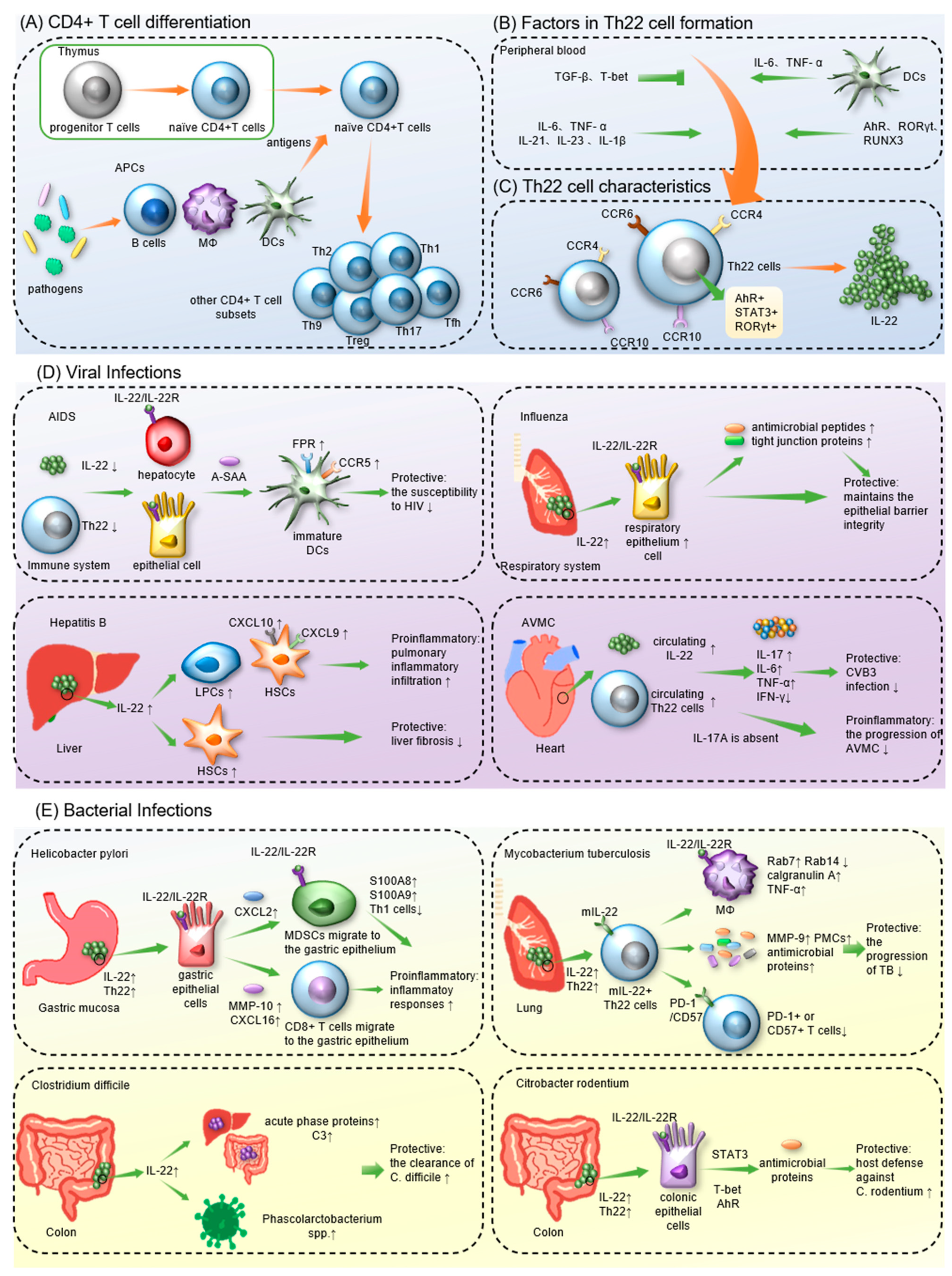

T helper 22 (Th22) cells, a newly defined CD4+ T-cell lineage, are characterized by their distinct cytokine profile, which primarily consists of IL-13, IL-22 and TNF-α. Th22 cells express a wide spectrum of chemokine receptors, such as CCR4, CCR6 and CCR10. The main effector molecule secreted by Th22 cells is IL-22, a member of the IL-10 family, which acts by binding to IL-22R and triggering a complex downstream signaling system. Th22 cells and IL-22 have been found to play variable roles in human immunity. In preventing the progression of infections such as HIV and influenza, Th22/IL-22 exhibited protective anti-inflammatory characteristics, and their deleterious proinflammatory activities have been demonstrated to exacerbate other illnesses, including hepatitis B and Helicobacter pylori infection.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Discovery of IL-22 and Th22 Cells

1.2. Factors in the Formation of Th22 cells and IL-22

1.3. The Effects of Th22/IL-22

2. Th22 Cells in Infectious Diseases

2.1. Th22 Cells in Viral Infections

2.1.1. COVID-19

2.1.2. AIDS

2.1.3. Hepatitis

2.1.4. Influenza

2.1.5. Acute Viral Myocarditis

2.1.6. Other Viral Infections

2.2. Th22 Cells in Bacterial Infections

2.2.1. Mycobacterium tuberculosis

2.2.2. Citrobacter Rodentium

2.2.3. Streptococcus pneumoniae

2.2.4. Helicobacter pylori

2.2.5. Other Bacterial Infections

References

- Ruterbusch, M.; Pruner, K.B.; Shehata, L.; Pepper, M. In Vivo CD4(+) T Cell Differentiation and Function: Revisiting the Th1/Th2 Paradigm. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 38, 705–725.

- Zhou, L.; Chong, M.M.; Littman, D.R. Plasticity of CD4+ T cell lineage differentiation. Immunity 2009, 30, 646–655.

- Xiao, F.; Han, M.; Rui, K.; Ai, X.; Tian, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, F.; Zhao, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Lu, L. New insights into follicular helper T cell response and regulation in autoimmune pathogenesis. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2021, 18, 1610–1612.

- Wang, W.; Sung, N.; Gilman-Sachs, A.; Kwak-Kim, J. T Helper (Th) Cell Profiles in Pregnancy and Recurrent Pregnancy Losses: Th1/Th2/Th9/Th17/Th22/Tfh Cells. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 2025.

- Chatzileontiadou, D.S.M.; Sloane, H.; Nguyen, A.T.; Gras, S.; Grant, E.J. The Many Faces of CD4(+) T Cells: Immunological and Structural Characteristics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 73.

- Dumoutier, L.; Louahed, J.; Renauld, J.C. Cloning and characterization of IL-10-related T cell-derived inducible factor (IL-TIF), a novel cytokine structurally related to IL-10 and inducible by IL-9. J. Immunol. 2000, 164, 1814–1819.

- Wolk, K.; Kunz, S.; Asadullah, K.; Sabat, R. Cutting edge: Immune cells as sources and targets of the IL-10 family members? J. Immunol. 2002, 168, 5397–5402.

- Sheppard, P.; Kindsvogel, W.; Xu, W.; Henderson, K.; Schlutsmeyer, S.; Whitmore, T.E.; Kuestner, R.; Garrigues, U.; Birks, C.; Roraback, J.; et al. IL-28, IL-29 and their class II cytokine receptor IL-28R. Nat. Immunol. 2003, 4, 63–68.

- Gurney, A.L. IL-22, a Th1 cytokine that targets the pancreas and select other peripheral tissues. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2004, 4, 669–677.

- Wolk, K.; Sabat, R. Interleukin-22: A novel T- and NK-cell derived cytokine that regulates the biology of tissue cells. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2006, 17, 367–380.

- Zheng, Y.; Danilenko, D.M.; Valdez, P.; Kasman, I.; Eastham-Anderson, J.; Wu, J.; Ouyang, W. Interleukin-22, a T(H)17 cytokine, mediates IL-23-induced dermal inflammation and acanthosis. Nature 2007, 445, 648–651.

- Kreymborg, K.; Etzensperger, R.; Dumoutier, L.; Haak, S.; Rebollo, A.; Buch, T.; Heppner, F.L.; Renauld, J.C.; Becher, B. IL-22 is expressed by Th17 cells in an IL-23-dependent fashion, but not required for the development of autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 8098–8104.

- Duhen, T.; Geiger, R.; Jarrossay, D.; Lanzavecchia, A.; Sallusto, F. Production of interleukin 22 but not interleukin 17 by a subset of human skin-homing memory T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2009, 10, 857–863.

- Trifari, S.; Kaplan, C.D.; Tran, E.H.; Crellin, N.K.; Spits, H. Identification of a human helper T cell population that has abundant production of interleukin 22 and is distinct from T(H)-17, T(H)1 and T(H)2 cells. Nat. Immunol. 2009, 10, 864–871.

- Eyerich, S.; Eyerich, K.; Pennino, D.; Carbone, T.; Nasorri, F.; Pallotta, S.; Cianfarani, F.; Odorisio, T.; Traidl-Hoffmann, C.; Behrendt, H.; et al. Th22 cells represent a distinct human T cell subset involved in epidermal immunity and remodeling. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 3573–3585.

- Dudakov, J.A.; Hanash, A.M.; van den Brink, M.R. Interleukin-22: Immunobiology and pathology. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 33, 747–785.

- Mousset, C.M.; Hobo, W.; Woestenenk, R.; Preijers, F.; Dolstra, H.; van der Waart, A.B. Comprehensive Phenotyping of T Cells Using Flow Cytometry. Cytometry. Part A J. Int. Soc. Anal. Cytol. 2019, 95, 647–654.

- Fujita, H.; Nograles, K.E.; Kikuchi, T.; Gonzalez, J.; Carucci, J.A.; Krueger, J.G. Human Langerhans cells induce distinct IL-22-producing CD4+ T cells lacking IL-17 production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 21795–21800.

- Sommer, A.; Fabri, M. Vitamin D regulates cytokine patterns secreted by dendritic cells to promote differentiation of IL-22-producing T cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130395.

- Lopez, D.V.; Al-Jaberi, F.A.H.; Damas, N.D.; Weinert, B.T.; Pus, U.; Torres-Rusillo, S.; Woetmann, A.; Ødum, N.; Bonefeld, C.M.; Kongsbak-Wismann, M.; et al. Vitamin D Inhibits IL-22 Production Through a Repressive Vitamin D Response Element in the il22 Promoter. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 715059.

- Huang, R.; Chen, X.; Long, Y.; Chen, R. MiR-31 promotes Th22 differentiation through targeting Bach2 in coronary heart disease. Biosci. Rep. 2019, 39, 986.

- Zeng, C.; Shao, Z.; Wei, Z.; Yao, J.; Wang, W.; Yin, L.; YangOu, H.; Xiong, D. The NOTCH-HES-1 axis is involved in promoting Th22 cell differentiation. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2021, 26, 7.

- Alam, M.S.; Maekawa, Y.; Kitamura, A.; Tanigaki, K.; Yoshimoto, T.; Kishihara, K.; Yasutomo, K. Notch signaling drives IL-22 secretion in CD4+ T cells by stimulating the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010, 107, 5943–5948.

- Niu, Y.; Ye, L.; Peng, W.; Wang, Z.; Wei, X.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Xiang, X.; Zhou, Q. IL-26 promotes the pathogenesis of malignant pleural effusion by enhancing CD4(+) IL-22(+) T-cell differentiation and inhibiting CD8(+) T-cell cytotoxicity. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2021, 110, 39–52.

- Fu, D.; Song, X.; Hu, H.; Sun, M.; Li, Z.; Tian, Z. Downregulation of RUNX3 moderates the frequency of Th17 and Th22 cells in patients with psoriasis. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 13, 4606–4612.

- Yang, J.; Yang, X.; Wang, L.; Li, M. B cells control lupus autoimmunity by inhibiting Th17 and promoting Th22 cells. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 164.

- Yeste, A.; Mascanfroni, I.D.; Nadeau, M.; Burns, E.J.; Tukpah, A.M.; Santiago, A.; Wu, C.; Patel, B.; Kumar, D.; Quintana, F.J. IL-21 induces IL-22 production in CD4+ T cells. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3753.

- Plank, M.W.; Kaiko, G.E.; Maltby, S.; Weaver, J.; Tay, H.L.; Shen, W.; Wilson, M.S.; Durum, S.K.; Foster, P.S. Th22 Cells Form a Distinct Th Lineage from Th17 Cells In Vitro with Unique Transcriptional Properties and Tbet-Dependent Th1 Plasticity. J. Immunol. 2017, 198, 2182–2190.

- Barnes, J.L.; Plank, M.W.; Asquith, K.; Maltby, S.; Sabino, L.R.; Kaiko, G.E.; Lochrin, A.; Horvat, J.C.; Mayall, J.R.; Kim, R.Y.; et al. T-helper 22 cells develop as a distinct lineage from Th17 cells during bacterial infection and phenotypic stability is regulated by T-bet. Mucosal Immunol. 2021, 14, 1077–1087.

- Ouyang, W.; O’Garra, A. IL-10 Family Cytokines IL-10 and IL-22: From Basic Science to Clinical Translation. Immunity 2019, 50, 871–891.

- Logsdon, N.J.; Jones, B.C.; Josephson, K.; Cook, J.; Walter, M.R. Comparison of interleukin-22 and interleukin-10 soluble receptor complexes. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. Off. J. Int. Soc. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2002, 22, 1099–1112.

- Li, J.; Tomkinson, K.N.; Tan, X.Y.; Wu, P.; Yan, G.; Spaulding, V.; Deng, B.; Annis-Freeman, B.; Heveron, K.; Zollner, R.; et al. Temporal associations between interleukin 22 and the extracellular domains of IL-22R and IL-10R2. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2004, 4, 693–708.

- Bleicher, L.; de Moura, P.R.; Watanabe, L.; Colau, D.; Dumoutier, L.; Renauld, J.C.; Polikarpov, I. Crystal structure of the IL-22/IL-22R1 complex and its implications for the IL-22 signaling mechanism. FEBS Lett. 2008, 582, 2985–2992.

- Wolk, K.; Kunz, S.; Witte, E.; Friedrich, M.; Asadullah, K.; Sabat, R. IL-22 increases the innate immunity of tissues. Immunity 2004, 21, 241–254.

- Jiang, Q.; Yang, G.; Xiao, F.; Xie, J.; Wang, S.; Lu, L.; Cui, D. Role of Th22 Cells in the Pathogenesis of Autoimmune Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 688066.

- Ahn, D.; Prince, A. Participation of the IL-10RB Related Cytokines, IL-22 and IFN-λ in Defense of the Airway Mucosal Barrier. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 300.

- Zheng, Y.; Valdez, P.A.; Danilenko, D.M.; Hu, Y.; Sa, S.M.; Gong, Q.; Abbas, A.R.; Modrusan, Z.; Ghilardi, N.; de Sauvage, F.J.; et al. Interleukin-22 mediates early host defense against attaching and effacing bacterial pathogens. Nat. Med. 2008, 14, 282–289.

- Wolk, K.; Witte, E.; Wallace, E.; Döcke, W.D.; Kunz, S.; Asadullah, K.; Volk, H.D.; Sterry, W.; Sabat, R. IL-22 regulates the expression of genes responsible for antimicrobial defense, cellular differentiation, and mobility in keratinocytes: A potential role in psoriasis. Eur. J. Immunol. 2006, 36, 1309–1323.

- Boniface, K.; Bernard, F.X.; Garcia, M.; Gurney, A.L.; Lecron, J.C.; Morel, F. IL-22 inhibits epidermal differentiation and induces proinflammatory gene expression and migration of human keratinocytes. J. Immunol. 2005, 174, 3695–3702.

- Wolk, K.; Haugen, H.S.; Xu, W.; Witte, E.; Waggie, K.; Anderson, M.; Vom Baur, E.; Witte, K.; Warszawska, K.; Philipp, S.; et al. IL-22 and IL-20 are key mediators of the epidermal alterations in psoriasis while IL-17 and IFN-gamma are not. J. Mol. Med. Berl.Ger. 2009, 87, 523–536.

- Hebert, K.D.; McLaughlin, N.; Galeas-Pena, M.; Zhang, Z.; Eddens, T.; Govero, A.; Pilewski, J.M.; Kolls, J.K.; Pociask, D.A. Targeting the IL-22/IL-22BP axis enhances tight junctions and reduces inflammation during influenza infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2020, 13, 64–74.

- Pickert, G.; Neufert, C.; Leppkes, M.; Zheng, Y.; Wittkopf, N.; Warntjen, M.; Lehr, H.A.; Hirth, S.; Weigmann, B.; Wirtz, S.; et al. STAT3 links IL-22 signaling in intestinal epithelial cells to mucosal wound healing. J. Exp. Med. 2009, 206, 1465–1472.

- Sonnenberg, G.F.; Nair, M.G.; Kirn, T.J.; Zaph, C.; Fouser, L.A.; Artis, D. Pathological versus protective functions of IL-22 in airway inflammation are regulated by IL-17A. J. Exp. Med. 2010, 207, 1293–1305.

- Aujla, S.J.; Chan, Y.R.; Zheng, M.; Fei, M.; Askew, D.J.; Pociask, D.A.; Reinhart, T.A.; McAllister, F.; Edeal, J.; Gaus, K.; et al. IL-22 mediates mucosal host defense against Gram-negative bacterial pneumonia. Nat. Med. 2008, 14, 275–281.

- Mitra, A.; Raychaudhuri, S.K.; Raychaudhuri, S.P. IL-22 induced cell proliferation is regulated by PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling cascade. Cytokine 2012, 60, 38–42.

- Li, H.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, Q.; Cui, Y.; Zhu, H.; Fang, M.; Zhou, X.; Sun, Z.; Yu, J. Interleukin-22 secreted by cancer-associated fibroblasts regulates the proliferation and metastasis of lung cancer cells via the PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling pathway. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2019, 11, 4077–4088.

- Nagalakshmi, M.L.; Rascle, A.; Zurawski, S.; Menon, S.; de Waal Malefyt, R. Interleukin-22 activates STAT3 and induces IL-10 by colon epithelial cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2004, 4, 679–691.

- Resham, S.; Saalim, M.; Manzoor, S.; Ahmad, H.; Bangash, T.A.; Latif, A.; Jaleel, S. Mechanistic study of interaction between IL-22 and HCV core protein in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma among liver transplant recipients. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 142, 104071.

- Dumoutier, L.; Van Roost, E.; Colau, D.; Renauld, J.C. Human interleukin-10-related T cell-derived inducible factor: Molecular cloning and functional characterization as an hepatocyte-stimulating factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 10144–10149.

- Quiñones-Mateu, M.E.; Lederman, M.M.; Feng, Z.; Chakraborty, B.; Weber, J.; Rangel, H.R.; Marotta, M.L.; Mirza, M.; Jiang, B.; Kiser, P.; et al. Human epithelial beta-defensins 2 and 3 inhibit HIV-1 replication. AIDS Lond. Engl. 2003, 17, F39–F48.

- Sertorio, M.; Hou, X.; Carmo, R.F.; Dessein, H.; Cabantous, S.; Abdelwahed, M.; Romano, A.; Albuquerque, F.; Vasconcelos, L.; Carmo, T.; et al. IL-22 and IL-22 binding protein (IL-22BP) regulate fibrosis and cirrhosis in hepatitis C virus and schistosome infections. Hepatol. Baltim. Md. 2015, 61, 1321–1331.

- Dumoutier, L.; Lejeune, D.; Colau, D.; Renauld, J.C. Cloning and characterization of IL-22 binding protein, a natural antagonist of IL-10-related T cell-derived inducible factor/IL-22. J. Immunol. 2001, 166, 7090–7095.

- Xu, W.; Presnell, S.R.; Parrish-Novak, J.; Kindsvogel, W.; Jaspers, S.; Chen, Z.; Dillon, S.R.; Gao, Z.; Gilbert, T.; Madden, K.; et al. A soluble class II cytokine receptor, IL-22RA2, is a naturally occurring IL-22 antagonist. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 9511–9516.

- Abood, R.N.; McHugh, K.J.; Rich, H.E.; Ortiz, M.A.; Tobin, J.M.; Ramanan, K.; Robinson, K.M.; Bomberger, J.M.; Kolls, J.K.; Manni, M.L.; et al. IL-22-binding protein exacerbates influenza, bacterial super-infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2019, 12, 1231–1243.

- Trevejo-Nunez, G.; Elsegeiny, W.; Aggor, F.E.Y.; Tweedle, J.L.; Kaplan, Z.; Gandhi, P.; Castillo, P.; Ferguson, A.; Alcorn, J.F.; Chen, K.; et al. Interleukin-22 (IL-22) Binding Protein Constrains IL-22 Activity, Host Defense, and Oxidative Phosphorylation Genes during Pneumococcal Pneumonia. Infect. Immun. 2019, 87, e00550-19.

- Hoffmann, J.P.; Kolls, J.K.; McCombs, J.E. Regulation and Function of ILC3s in Pulmonary Infections. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 672523.

- Pociask, D.A.; Scheller, E.V.; Mandalapu, S.; McHugh, K.J.; Enelow, R.I.; Fattman, C.L.; Kolls, J.K.; Alcorn, J.F. IL-22 is essential for lung epithelial repair following influenza infection. Am. J. Pathol. 2013, 182, 1286–1296.

- Das, S.; St Croix, C.; Good, M.; Chen, J.; Zhao, J.; Hu, S.; Ross, M.; Myerburg, M.M.; Pilewski, J.M.; Williams, J.; et al. Interleukin-22 Inhibits Respiratory Syncytial Virus Production by Blocking Virus-Mediated Subversion of Cellular Autophagy. iScience 2020, 23, 101256.

- Barhoum, P.; Pineton de Chambrun, M.; Dorgham, K.; Kerneis, M.; Burrel, S.; Quentric, P.; Parizot, C.; Chommeloux, J.; Bréchot, N.; Moyon, Q.; et al. Phenotypic Heterogeneity of Fulminant COVID-19--Related Myocarditis in Adults. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 80, 299–312.

- Albayrak, N.; Orte Cano, C.; Karimi, S.; Dogahe, D.; Van Praet, A.; Godefroid, A.; Del Marmol, V.; Grimaldi, D.; Bondue, B.; Van Vooren, J.P.; et al. Distinct Expression Patterns of Interleukin-22 Receptor 1 on Blood Hematopoietic Cells in SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 769839.

- Ahmed Mostafa, G.; Mohamed Ibrahim, H.; Al Sayed Shehab, A.; Mohamed Magdy, S.; AboAbdoun Soliman, N.; Fathy El-Sherif, D. Up-regulated serum levels of interleukin (IL)-17A and IL-22 in Egyptian pediatric patients with COVID-19 and MIS-C: Relation to the disease outcome. Cytokine 2022, 154, 155870.

- Ellison-Hughes, G.M.; Colley, L.; O’Brien, K.A.; Roberts, K.A.; Agbaedeng, T.A.; Ross, M.D. The Role of MSC Therapy in Attenuating the Damaging Effects of the Cytokine Storm Induced by COVID-19 on the Heart and Cardiovascular System. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 602183.

- Guzik, T.J.; Mohiddin, S.A.; Dimarco, A.; Patel, V.; Savvatis, K.; Marelli-Berg, F.M.; Madhur, M.S.; Tomaszewski, M.; Maffia, P.; D’Acquisto, F.; et al. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system: Implications for risk assessment, diagnosis, and treatment options. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 116, 1666–1687.

- Shimabukuro-Vornhagen, A.; Gödel, P.; Subklewe, M.; Stemmler, H.J.; Schlößer, H.A.; Schlaak, M.; Kochanek, M.; Böll, B.; von Bergwelt-Baildon, M.S. Cytokine release syndrome. J. Immunother. Cancer 2018, 6, 56.

- Lee, D.W.; Gardner, R.; Porter, D.L.; Louis, C.U.; Ahmed, N.; Jensen, M.; Grupp, S.A.; Mackall, C.L. Current concepts in the diagnosis and management of cytokine release syndrome. Blood 2014, 124, 188–195.

- Fanales-Belasio, E.; Raimondo, M.; Suligoi, B.; Buttò, S. HIV virology and pathogenetic mechanisms of infection: A brief overview. Ann. Dell’istituto Super. Di Sanita 2010, 46, 5–14.

- Missé, D.; Yssel, H.; Trabattoni, D.; Oblet, C.; Lo Caputo, S.; Mazzotta, F.; Pène, J.; Gonzalez, J.P.; Clerici, M.; Veas, F. IL-22 participates in an innate anti-HIV-1 host-resistance network through acute-phase protein induction. J. Immunol. 2007, 178, 407–415.

- Morou, A.; Brunet-Ratnasingham, E.; Dubé, M.; Charlebois, R.; Mercier, E.; Darko, S.; Brassard, N.; Nganou-Makamdop, K.; Arumugam, S.; Gendron-Lepage, G.; et al. Altered differentiation is central to HIV-specific CD4(+) T cell dysfunction in progressive disease. Nat. Immunol. 2019, 20, 1059–1070.

- Uhlar, C.M.; Burgess, C.J.; Sharp, P.M.; Whitehead, A.S. Evolution of the serum amyloid A (SAA) protein superfamily. Genomics 1994, 19, 228–235.

- McKinnon, L.R.; Kaul, R. Quality and quantity: Mucosal CD4+ T cells and HIV susceptibility. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2012, 7, 195–202.

- Veazey, R.S. Intestinal CD4 Depletion in HIV / SIV Infection. Curr. Immunol. Rev. 2019, 15, 76–91.

- Ryan, E.S.; Micci, L.; Fromentin, R.; Paganini, S.; McGary, C.S.; Easley, K.; Chomont, N.; Paiardini, M. Loss of Function of Intestinal IL-17 and IL-22 Producing Cells Contributes to Inflammation and Viral Persistence in SIV-Infected Rhesus Macaques. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005412.

- Sonnenberg, G.F.; Monticelli, L.A.; Alenghat, T.; Fung, T.C.; Hutnick, N.A.; Kunisawa, J.; Shibata, N.; Grunberg, S.; Sinha, R.; Zahm, A.M.; et al. Innate lymphoid cells promote anatomical containment of lymphoid-resident commensal bacteria. Science 2012, 336, 1321–1325.

- Arias, J.F.; Nishihara, R.; Bala, M.; Ikuta, K. High systemic levels of interleukin-10, interleukin-22 and C-reactive protein in Indian patients are associated with low in vitro replication of HIV-1 subtype C viruses. Retrovirology 2010, 7, 15.

- Campillo-Gimenez, L.; Casulli, S.; Dudoit, Y.; Seang, S.; Carcelain, G.; Lambert-Niclot, S.; Appay, V.; Autran, B.; Tubiana, R.; Elbim, C. Neutrophils in antiretroviral therapy-controlled HIV demonstrate hyperactivation associated with a specific IL-17/IL-22 environment. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 134, 1142–1152.

- Fernandes, S.M.; Pires, A.R.; Matoso, P.; Ferreira, C.; Nunes-Cabaço, H.; Correia, L.; Valadas, E.; Poças, J.; Pacheco, P.; Veiga-Fernandes, H.; et al. HIV-2 infection is associated with preserved GALT homeostasis and epithelial integrity despite ongoing mucosal viral replication. Mucosal Immunol. 2018, 11, 236–248.

- Khaitan, A.; Kilberg, M.; Kravietz, A.; Ilmet, T.; Tastan, C.; Mwamzuka, M.; Marshed, F.; Liu, M.; Ahmed, A.; Borkowsky, W.; et al. HIV-Infected Children Have Lower Frequencies of CD8+ Mucosal-Associated Invariant T (MAIT) Cells that Correlate with Innate, Th17 and Th22 Cell Subsets. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161786.

- Le Bourhis, L.; Martin, E.; Péguillet, I.; Guihot, A.; Froux, N.; Coré, M.; Lévy, E.; Dusseaux, M.; Meyssonnier, V.; Premel, V.; et al. Antimicrobial activity of mucosal-associated invariant T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 701–708.

- Ussher, J.E.; Klenerman, P.; Willberg, C.B. Mucosal-associated invariant T-cells: New players in anti-bacterial immunity. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 450.

- Meyer-Myklestad, M.H.; Medhus, A.W.; Lorvik, K.B.; Seljeflot, I.; Hansen, S.H.; Holm, K.; Stiksrud, B.; Trøseid, M.; Hov, J.R.; Kvale, D.; et al. Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected Immunological Nonresponders Have Colon-Restricted Gut Mucosal Immune Dysfunction. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 225, 661–674.

- Lok, A.S.F.; McMahon, B.J. Chronic hepatitis B. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 1682–1683.

- Manns, M.P.; McHutchison, J.G.; Gordon, S.C.; Rustgi, V.K.; Shiffman, M.; Reindollar, R.; Goodman, Z.D.; Koury, K.; Ling, M.; Albrecht, J.K. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: A randomised trial. Lancet 2001, 358, 958–965.

- Lauer, G.M.; Walker, B.D. Hepatitis C virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 41–52.

- Dambacher, J.; Beigel, F.; Zitzmann, K.; Heeg, M.H.; Göke, B.; Diepolder, H.M.; Auernhammer, C.J.; Brand, S. The role of interleukin-22 in hepatitis C virus infection. Cytokine 2008, 41, 209–216.

- Zenewicz, L.A.; Yancopoulos, G.D.; Valenzuela, D.M.; Murphy, A.J.; Karow, M.; Flavell, R.A. Interleukin-22 but not interleukin-17 provides protection to hepatocytes during acute liver inflammation. Immunity 2007, 27, 647–659.

- Feng, D.; Kong, X.; Weng, H.; Park, O.; Wang, H.; Dooley, S.; Gershwin, M.E.; Gao, B. Interleukin-22 promotes proliferation of liver stem/progenitor cells in mice and patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Gastroenterology 2012, 143, 188–198.

- Zheng, W.P.; Zhang, B.Y.; Shen, Z.Y.; Yin, M.L.; Cao, Y.; Song, H.L. Biological effects of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells on hepatitis B virus in vitro. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 15, 2551–2559.

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Luan, Y.; Zou, Z.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Jin, L.; Zhou, C.; Fu, J.; Gao, B.; et al. Pathological functions of interleukin-22 in chronic liver inflammation and fibrosis with hepatitis B virus infection by promoting T helper 17 cell recruitment. Hepatology 2014, 59, 1331–1342.

- Mo, R.; Wang, P.; Lai, R.; Li, F.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, S.; Zhao, G.; Guo, S.; Zhou, H.; Lin, L.; et al. Persistently elevated circulating Th22 reversely correlates with prognosis in HBV-related acute-on-chronic liver failure. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 32, 677–686.

- Kong, X.; Feng, D.; Wang, H.; Hong, F.; Bertola, A.; Wang, F.S.; Gao, B. Interleukin-22 induces hepatic stellate cell senescence and restricts liver fibrosis in mice. Hepatology 2012, 56, 1150–1159.

- Xiang, X.; Gui, H.; King, N.J.; Cole, L.; Wang, H.; Xie, Q.; Bao, S. IL-22 and non-ELR-CXC chemokine expression in chronic hepatitis B virus-infected liver. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2012, 90, 611–619.

- Gao, W.; Fan, Y.C.; Zhang, J.Y.; Zheng, M.H. Emerging Role of Interleukin 22 in Hepatitis B Virus Infection: A Double-edged Sword. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2013, 1, 103–108.

- Cobleigh, M.A.; Robek, M.D. Protective and pathological properties of IL-22 in liver disease: Implications for viral hepatitis. Am. J. Pathol. 2013, 182, 21–28.

- Foster, R.G.; Golden-Mason, L.; Rutebemberwa, A.; Rosen, H.R. Interleukin (IL)-17/IL-22-producing T cells enriched within the liver of patients with chronic hepatitis C viral (HCV) infection. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2012, 57, 381–389.

- Wu, L.Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Guo, C.; Li, H.; Li, W.; Jin, X.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, P.; Wei, L.; et al. Up-regulation of interleukin-22 mediates liver fibrosis via activating hepatic stellate cells in patients with hepatitis C. Clin. Immunol. 2015, 158, 77–87.

- Kong, F.; Zhang, W.; Feng, B.; Zhang, H.; Rao, H.; Wang, J.; Cong, X.; Wei, L. Abnormal CD4 + T helper (Th) 1 cells and activated memory B cells are associated with type III asymptomatic mixed cryoglobulinemia in HCV infection. Virol. J. 2015, 12, 100.

- De Brito, R.; do Carmo, R.F.; Silva, B.M.S.; Costa, A.C.S.; Rocha, S.W.S.; Vasconcelos, L.R.S.; Pereira, L.; de Moura, P. Liver expression of IL-22, IL-22R1 and IL-22BP in patients with chronic hepatitis C with different fibrosis stages. Cytokine 2022, 150, 155784.

- Zenewicz, L.A. IL-22 Binding Protein (IL-22BP) in the Regulation of IL-22 Biology. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 766586.

- Voglis, S.; Moos, S.; Kloos, L.; Wanke, F.; Zayoud, M.; Pelczar, P.; Giannou, A.D.; Pezer, S.; Albers, M.; Luessi, F.; et al. Regulation of IL-22BP in psoriasis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5085.

- Huber, S.; Gagliani, N.; Zenewicz, L.A.; Huber, F.J.; Bosurgi, L.; Hu, B.; Hedl, M.; Zhang, W.; O’Connor, W.; Murphy, A.J.; et al. IL-22BP is regulated by the inflammasome and modulates tumorigenesis in the intestine. Nature 2012, 491, 259–263.

- Wu, L.; Zhao, J. Does IL-22 protect against liver fibrosis in hepatitis C virus infection? Hepatology 2015, 62, 1919.

- Hebert, K.D.; McLaughlin, N.; Zhang, Z.; Cipriani, A.; Alcorn, J.F.; Pociask, D.A. IL-22Ra1 is induced during influenza infection by direct and indirect TLR3 induction of STAT1. Respir. Res. 2019, 20, 184.

- Guo, H.; Topham, D.J. Interleukin-22 (IL-22) production by pulmonary Natural Killer cells and the potential role of IL-22 during primary influenza virus infection. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 7750–7759.

- Paget, C.; Ivanov, S.; Fontaine, J.; Renneson, J.; Blanc, F.; Pichavant, M.; Dumoutier, L.; Ryffel, B.; Renauld, J.C.; Gosset, P.; et al. Interleukin-22 is produced by invariant natural killer T lymphocytes during influenza A virus infection: Potential role in protection against lung epithelial damages. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 8816–8829.

- Kumar, P.; Thakar, M.S.; Ouyang, W.; Malarkannan, S. IL-22 from conventional NK cells is epithelial regenerative and inflammation protective during influenza infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2013, 6, 69–82.

- Kudva, A.; Scheller, E.V.; Robinson, K.M.; Crowe, C.R.; Choi, S.M.; Slight, S.R.; Khader, S.A.; Dubin, P.J.; Enelow, R.I.; Kolls, J.K.; et al. Influenza A inhibits Th17-mediated host defense against bacterial pneumonia in mice. J. Immunol. 2011, 186, 1666–1674.

- Barthelemy, A.; Sencio, V.; Soulard, D.; Deruyter, L.; Faveeuw, C.; Le Goffic, R.; Trottein, F. Interleukin-22 Immunotherapy during Severe Influenza Enhances Lung Tissue Integrity and Reduces Secondary Bacterial Systemic Invasion. Infect. Immun. 2018, 86, e00706-17.

- Kaarteenaho, R.; Merikallio, H.; Lehtonen, S.; Harju, T.; Soini, Y. Divergent expression of claudin -1, -3, -4, -5 and -7 in developing human lung. Respir. Res. 2010, 11, 59.

- Eaton, D.C.; Helms, M.N.; Koval, M.; Bao, H.F.; Jain, L. The contribution of epithelial sodium channels to alveolar function in health and disease. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2009, 71, 403–423.

- Ivanov, S.; Renneson, J.; Fontaine, J.; Barthelemy, A.; Paget, C.; Fernandez, E.M.; Blanc, F.; De Trez, C.; Van Maele, L.; Dumoutier, L.; et al. Interleukin-22 reduces lung inflammation during influenza A virus infection and protects against secondary bacterial infection. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 6911–6924.

- Xie, Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, L.; Ning, P.; Luo, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, L.; Zheng, Y.; Gao, Z. Specific Cytokine Profiles Predict the Severity of Influenza A Pneumonia: A Prospectively Multicenter Pilot Study. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 9533044.

- Crocker, S.J.; Frausto, R.F.; Whitmire, J.K.; Benning, N.; Milner, R.; Whitton, J.L. Amelioration of coxsackievirus B3-mediated myocarditis by inhibition of tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinase-1. Am. J. Pathol. 2007, 171, 1762–1773.

- Kong, Q.; Wu, W.; Yang, F.; Liu, Y.; Xue, Y.; Gao, M.; Lai, W.; Pan, X.; Yan, Y.; Pang, Y.; et al. Increased expressions of IL-22 and Th22 cells in the coxsackievirus B3-Induced mice acute viral myocarditis. Virol. J. 2012, 9, 232.

- Guo, Y.; Wu, W.; Cen, Z.; Li, X.; Kong, Q.; Zhou, Q. IL-22-producing Th22 cells play a protective role in CVB3-induced chronic myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy by inhibiting myocardial fibrosis. Virol. J. 2014, 11, 230.

- Kong, Q.; Xue, Y.; Wu, W.; Yang, F.; Liu, Y.; Gao, M.; Lai, W.; Pan, X. IL-22 exacerbates the severity of CVB3-induced acute viral myocarditis in IL-17A-deficient mice. Mol. Med. Rep. 2013, 7, 1329–1335.

- Chan, K.P.; Goh, K.T.; Chong, C.Y.; Teo, E.S.; Lau, G.; Ling, A.E. Epidemic hand, foot and mouth disease caused by human enterovirus 71, Singapore. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2003, 9, 78–85.

- Zhang, S.Y.; Xu, M.Y.; Xu, H.M.; Li, X.J.; Ding, S.J.; Wang, X.J.; Li, T.Y.; Lu, Q.B. Immunologic Characterization of Cytokine Responses to Enterovirus 71 and Coxsackievirus A16 Infection in Children. Medicine 2015, 94, e1137.

- Cui, D.; Zhong, F.; Lin, J.; Wu, Y.; Long, Q.; Yang, X.; Zhu, Q.; Huang, L.; Mao, Q.; Huo, Z.; et al. Changes of circulating Th22 cells in children with hand, foot, and mouth disease caused by enterovirus 71 infection. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 29370–29382.

- Hall, C.B. Respiratory syncytial virus and parainfluenza virus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 344, 1917–1928.

- Nair, H.; Nokes, D.J.; Gessner, B.D.; Dherani, M.; Madhi, S.A.; Singleton, R.J.; O’Brien, K.L.; Roca, A.; Wright, P.F.; Bruce, N.; et al. Global burden of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2010, 375, 1545–1555.

- Widmer, K.; Zhu, Y.; Williams, J.V.; Griffin, M.R.; Edwards, K.M.; Talbot, H.K. Rates of hospitalizations for respiratory syncytial virus, human metapneumovirus, and influenza virus in older adults. J. Infect. Dis. 2012, 206, 56–62.

- Geevarghese, B.; Weinberg, A. Cell-mediated immune responses to respiratory syncytial virus infection: Magnitude, kinetics, and correlates with morbidity and age. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2014, 10, 1047–1056.

- Soenjoyo, K.R.; Chua, B.W.B.; Wee, L.W.Y.; Koh, M.J.A.; Ang, S.B. Treatment of cutaneous viral warts in children: A review. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e14034.

- Marie, R.E.M.; Abuzeid, A.; Attia, F.M.; Anani, M.M.; Gomaa, A.H.A.; Atef, L.M. Serum level of interleukin-22 in patients with cutaneous warts: A case-control study. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 20, 1782–1787.

- Ferreira, M.S.; Júnior, P.S.B.; Cerqueira, V.D.; Rivero, G.R.C.; Júnior, C.A.O.; Castro, P.H.G.; Silva, G.A.D.; Silva, W.B.D.; Imbeloni, A.A.; Sousa, J.R.; et al. Experimental yellow fever virus infection in the squirrel monkey (Saimiri spp.) I: Gross anatomical and histopathological findings in organs at necropsy. Mem. Do Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2020, 115, e190501.

- De Rodaniche, E.; Galindo, P. Isolation of yellow fever virus from Haemagogus mesodentatus, H. equinus and Sabethes chloropterus captured in Guatemala in 1956. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1957, 6, 232–237.

- Mendes, C.C.H.; de Sousa, J.R.; Olímpio, F.A.; Falcão, L.F.M.; Carvalho, M.L.G.; da Costa Lopes, J.; Martins Filho, A.J.; do Socorro Cabral Miranda, V.; Dos Santos, L.C.; da Silva Vilacoert, F.S.; et al. Th22 cytokines and yellow fever: Possible implications for the immunopathogenesis of human liver infection. Cytokine 2022, 157, 155924.

- Flynn, J.L.; Chan, J. Immunology of tuberculosis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2001, 19, 93–129.

- Imperiale, B.R.; García, A.; Minotti, A.; González Montaner, P.; Moracho, L.; Morcillo, N.S.; Palmero, D.J.; Sasiain, M.D.C.; de la Barrera, S. Th22 response induced by Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains is closely related to severity of pulmonary lesions and bacillary load in patients with multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2021, 203, 267–280.

- Cowan, J.; Pandey, S.; Filion, L.G.; Angel, J.B.; Kumar, A.; Cameron, D.W. Comparison of interferon-γ-, interleukin (IL)-17- and IL-22-expressing CD4 T cells, IL-22-expressing granulocytes and proinflammatory cytokines during latent and active tuberculosis infection. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2012, 167, 317–329.

- Bunjun, R.; Omondi, F.M.A.; Makatsa, M.S.; Keeton, R.; Wendoh, J.M.; Müller, T.L.; Prentice, C.S.L.; Wilkinson, R.J.; Riou, C.; Burgers, W.A. Th22 Cells Are a Major Contributor to the Mycobacterial CD4(+) T Cell Response and Are Depleted During HIV Infection. J. Immunol. 2021, 207, 1239–1249.

- Treerat, P.; Prince, O.; Cruz-Lagunas, A.; Muñoz-Torrico, M.; Salazar-Lezama, M.A.; Selman, M.; Fallert-Junecko, B.; Reinhardt, T.A.; Alcorn, J.F.; Kaushal, D.; et al. Novel role for IL-22 in protection during chronic Mycobacterium tuberculosis HN878 infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2017, 10, 1069–1081.

- Behrends, J.; Renauld, J.C.; Ehlers, S.; Hölscher, C. IL-22 is mainly produced by IFNγ-secreting cells but is dispensable for host protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e57379.

- Scriba, T.J.; Kalsdorf, B.; Abrahams, D.A.; Isaacs, F.; Hofmeister, J.; Black, G.; Hassan, H.Y.; Wilkinson, R.J.; Walzl, G.; Gelderbloem, S.J.; et al. Distinct, specific IL-17- and IL-22-producing CD4+ T cell subsets contribute to the human anti-mycobacterial immune response. J. Immunol. 2008, 180, 1962–1970.

- Matthews, K.; Wilkinson, K.A.; Kalsdorf, B.; Roberts, T.; Diacon, A.; Walzl, G.; Wolske, J.; Ntsekhe, M.; Syed, F.; Russell, J.; et al. Predominance of interleukin-22 over interleukin-17 at the site of disease in human tuberculosis. Tuberc. Edinb. Scotl. 2011, 91, 587–593.

- Yao, S.; Huang, D.; Chen, C.Y.; Halliday, L.; Zeng, G.; Wang, R.C.; Chen, Z.W. Differentiation, distribution and gammadelta T cell-driven regulation of IL-22-producing T cells in tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1000789.

- Zeng, G.; Chen, C.Y.; Huang, D.; Yao, S.; Wang, R.C.; Chen, Z.W. Membrane-bound IL-22 after de novo production in tuberculosis and anti-Mycobacterium tuberculosis effector function of IL-22+ CD4+ T cells. J. Immunol. 2011, 187, 190–199.

- Ye, Z.J.; Zhou, Q.; Yuan, M.L.; Du, R.H.; Yang, W.B.; Xiong, X.Z.; Huang, B.; Shi, H.Z. Differentiation and recruitment of IL-22-producing helper T cells stimulated by pleural mesothelial cells in tuberculous pleurisy. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 185, 660–669.

- Ardain, A.; Domingo-Gonzalez, R.; Das, S.; Kazer, S.W.; Howard, N.C.; Singh, A.; Ahmed, M.; Nhamoyebonde, S.; Rangel-Moreno, J.; Ogongo, P.; et al. Group 3 innate lymphoid cells mediate early protective immunity against tuberculosis. Nature 2019, 570, 528–532.

- Dhiman, R.; Venkatasubramanian, S.; Paidipally, P.; Barnes, P.F.; Tvinnereim, A.; Vankayalapati, R. Interleukin 22 inhibits intracellular growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by enhancing calgranulin A expression. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 209, 578–587.

- Dhiman, R.; Indramohan, M.; Barnes, P.F.; Nayak, R.C.; Paidipally, P.; Rao, L.V.; Vankayalapati, R. IL-22 produced by human NK cells inhibits growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by enhancing phagolysosomal fusion. J. Immunol. 2009, 183, 6639–6645.

- Hrabec, E.; Strek, M.; Zieba, M.; Kwiatkowska, S.; Hrabec, Z. Circulation level of matrix metalloproteinase-9 is correlated with disease severity in tuberculosis patients. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. Off. J. Int. Union Against Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2002, 6, 713–719.

- Backert, I.; Koralov, S.B.; Wirtz, S.; Kitowski, V.; Billmeier, U.; Martini, E.; Hofmann, K.; Hildner, K.; Wittkopf, N.; Brecht, K.; et al. STAT3 activation in Th17 and Th22 cells controls IL-22-mediated epithelial host defense during infectious colitis. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 3779–3791.

- Basu, R.; O’Quinn, D.B.; Silberger, D.J.; Schoeb, T.R.; Fouser, L.; Ouyang, W.; Hatton, R.D.; Weaver, C.T. Th22 cells are an important source of IL-22 for host protection against enteropathogenic bacteria. Immunity 2012, 37, 1061–1075.

- Brandl, K.; Plitas, G.; Mihu, C.N.; Ubeda, C.; Jia, T.; Fleisher, M.; Schnabl, B.; DeMatteo, R.P.; Pamer, E.G. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci exploit antibiotic-induced innate immune deficits. Nature 2008, 455, 804–807.

- Kinnebrew, M.A.; Buffie, C.G.; Diehl, G.E.; Zenewicz, L.A.; Leiner, I.; Hohl, T.M.; Flavell, R.A.; Littman, D.R.; Pamer, E.G. Interleukin 23 production by intestinal CD103(+)CD11b(+) dendritic cells in response to bacterial flagellin enhances mucosal innate immune defense. Immunity 2012, 36, 276–287.

- Kinnebrew, M.A.; Ubeda, C.; Zenewicz, L.A.; Smith, N.; Flavell, R.A.; Pamer, E.G. Bacterial flagellin stimulates Toll-like receptor 5-dependent defense against vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 201, 534–543.

- Van Maele, L.; Carnoy, C.; Cayet, D.; Ivanov, S.; Porte, R.; Deruy, E.; Chabalgoity, J.A.; Renauld, J.C.; Eberl, G.; Benecke, A.G.; et al. Activation of Type 3 innate lymphoid cells and interleukin 22 secretion in the lungs during Streptococcus pneumoniae infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 210, 493–503.

- Trevejo-Nunez, G.; Elsegeiny, W.; Conboy, P.; Chen, K.; Kolls, J.K. Critical Role of IL-22/IL22-RA1 Signaling in Pneumococcal Pneumonia. J. Immunol. 2016, 197, 1877–1883.

- Dixon, B.; Hossain, R.; Patel, R.V.; Algood, H.M.S. Th17 Cells in Helicobacter pylori Infection: A Dichotomy of Help and Harm. Infect. Immun. 2019, 87, e00363-19.

- Suerbaum, S.; Michetti, P. Helicobacter pylori infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 1175–1186.

- Zhuang, Y.; Cheng, P.; Liu, X.F.; Peng, L.S.; Li, B.S.; Wang, T.T.; Chen, N.; Li, W.H.; Shi, Y.; Chen, W.; et al. A pro-inflammatory role for Th22 cells in Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis. Gut 2015, 64, 1368–1378.

- Lv, Y.P.; Cheng, P.; Zhang, J.Y.; Mao, F.Y.; Teng, Y.S.; Liu, Y.G.; Kong, H.; Wu, X.L.; Hao, C.J.; Han, B.; et al. Helicobacter pylori-induced matrix metallopeptidase-10 promotes gastric bacterial colonization and gastritis. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau6547.

- Dixon, B.R.; Radin, J.N.; Piazuelo, M.B.; Contreras, D.C.; Algood, H.M. IL-17a and IL-22 Induce Expression of Antimicrobials in Gastrointestinal Epithelial Cells and May Contribute to Epithelial Cell Defense against Helicobacter pylori. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148514.

- Carroll, K.C.; Bartlett, J.G. Biology of Clostridium difficile: Implications for epidemiology and diagnosis. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 65, 501–521.

- Hasegawa, M.; Yada, S.; Liu, M.Z.; Kamada, N.; Muñoz-Planillo, R.; Do, N.; Núñez, G.; Inohara, N. Interleukin-22 regulates the complement system to promote resistance against pathobionts after pathogen-induced intestinal damage. Immunity 2014, 41, 620–632.

- Nagao-Kitamoto, H.; Leslie, J.L.; Kitamoto, S.; Jin, C.; Thomsson, K.A.; Gillilland, M.G., 3rd; Kuffa, P.; Goto, Y.; Jenq, R.R.; Ishii, C.; et al. Interleukin-22-mediated host glycosylation prevents Clostridioides difficile infection by modulating the metabolic activity of the gut microbiota. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 608–617.

- Gomez-Simmonds, A.; Greenman, M.; Sullivan, S.B.; Tanner, J.P.; Sowash, M.G.; Whittier, S.; Uhlemann, A.C. Population Structure of Klebsiella pneumoniae Causing Bloodstream Infections at a New York City Tertiary Care Hospital: Diversification of Multidrug-Resistant Isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 2060–2067.

- Ahn, D.; Wickersham, M.; Riquelme, S.; Prince, A. The Effects of IFN-λ on Epithelial Barrier Function Contribute to Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258 Pneumonia. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2019, 60, 158–166.

- Flo, T.H.; Smith, K.D.; Sato, S.; Rodriguez, D.J.; Holmes, M.A.; Strong, R.K.; Akira, S.; Aderem, A. Lipocalin 2 mediates an innate immune response to bacterial infection by sequestrating iron. Nature 2004, 432, 917–921.

- Berger, T.; Togawa, A.; Duncan, G.S.; Elia, A.J.; You-Ten, A.; Wakeham, A.; Fong, H.E.; Cheung, C.C.; Mak, T.W. Lipocalin 2-deficient mice exhibit increased sensitivity to Escherichia coli infection but not to ischemia-reperfusion injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 1834–1839.

- Matthay, M.A.; Ware, L.B.; Zimmerman, G.A. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 2731–2740.

- Broquet, A.; Jacqueline, C.; Davieau, M.; Besbes, A.; Roquilly, A.; Martin, J.; Caillon, J.; Dumoutier, L.; Renauld, J.C.; Heslan, M.; et al. Interleukin-22 level is negatively correlated with neutrophil recruitment in the lungs in a Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia model. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11010.

- Broquet, A.; Besbes, A.; Martin, J.; Jacqueline, C.; Vourc’h, M.; Roquilly, A.; Caillon, J.; Josien, R.; Asehnoune, K. Interleukin-22 regulates interferon lambda expression in a mice model of pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Mol. Immunol. 2020, 118, 52–59.

- Guillon, A.; Brea, D.; Morello, E.; Tang, A.; Jouan, Y.; Ramphal, R.; Korkmaz, B.; Perez-Cruz, M.; Trottein, F.; O’Callaghan, R.J.; et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa proteolytically alters the interleukin 22-dependent lung mucosal defense. Virulence 2017, 8, 810–820.

- Guillon, A.; Brea, D.; Luczka, E.; Hervé, V.; Hasanat, S.; Thorey, C.; Pérez-Cruz, M.; Hordeaux, J.; Mankikian, J.; Gosset, P.; et al. Inactivation of the interleukin-22 pathway in the airways of cystic fibrosis patients. Cytokine 2019, 113, 470–474.

- Hohmann, E.L. Nontyphoidal salmonellosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2001, 32, 263–269.

- Raffatellu, M.; George, M.D.; Akiyama, Y.; Hornsby, M.J.; Nuccio, S.P.; Paixao, T.A.; Butler, B.P.; Chu, H.; Santos, R.L.; Berger, T.; et al. Lipocalin-2 resistance confers an advantage to Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium for growth and survival in the inflamed intestine. Cell Host Microbe 2009, 5, 476–486.

- Liu, J.Z.; Jellbauer, S.; Poe, A.J.; Ton, V.; Pesciaroli, M.; Kehl-Fie, T.E.; Restrepo, N.A.; Hosking, M.P.; Edwards, R.A.; Battistoni, A.; et al. Zinc sequestration by the neutrophil protein calprotectin enhances Salmonella growth in the inflamed gut. Cell Host Microbe 2012, 11, 227–239.

- Kehl-Fie, T.E.; Skaar, E.P. Nutritional immunity beyond iron: A role for manganese and zinc. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2010, 14, 218–224.

- Xiong, L.; Wang, S.; Dean, J.W.; Oliff, K.N.; Jobin, C.; Curtiss, R., 3rd; Zhou, L. Group 3 innate lymphoid cell pyroptosis represents a host defence mechanism against Salmonella infection. Nat. Microbiol. 2022, 7, 1087–1099.