You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jarmo-Charles Julian Kalinski | -- | 1819 | 2022-12-21 12:22:49 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | -3 word(s) | 1816 | 2022-12-22 04:16:56 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Kalinski, J.J.; Polyzois, A.; Waterworth, S.C.; Noundou, X.S.; Dorrington, R.A. Pyrroloiminoquinones. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39041 (accessed on 02 January 2026).

Kalinski JJ, Polyzois A, Waterworth SC, Noundou XS, Dorrington RA. Pyrroloiminoquinones. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39041. Accessed January 02, 2026.

Kalinski, Jarmo-Charles J., Alexandros Polyzois, Samantha C. Waterworth, Xavier Siwe Noundou, Rosemary A. Dorrington. "Pyrroloiminoquinones" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39041 (accessed January 02, 2026).

Kalinski, J.J., Polyzois, A., Waterworth, S.C., Noundou, X.S., & Dorrington, R.A. (2022, December 21). Pyrroloiminoquinones. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39041

Kalinski, Jarmo-Charles J., et al. "Pyrroloiminoquinones." Encyclopedia. Web. 21 December, 2022.

Copy Citation

Pyrroloiminoquinones are a group of cytotoxic alkaloids most commonly isolated from marine sponges. Structurally, they are based on a tricyclic pyrrolo[4,3,2-de]quinoline core and encompass marine natural products such as makaluvamines, tsitsikammamines and discorhabdins.

makaluvamine

damirone

discorhabdin

batzelline

tsitsikammamine

1. Introduction

Pyrroloiminoquinones are a large and diverse group of natural products that have been isolated predominantly from marine sponges [1][2][3][4]. They are considered to be potential drug leads due to their significant inhibition of cell proliferation in various cancer cell lines, including promising in vivo activity against several tumor types [5][6][7][8][9] and inhibition of Plasmodium berghei parasitemia [10] in mouse models. In addition, pyrroloiminoquinones have been shown to exhibit antiviral [11][12], antifungal [13][14][15] and antibacterial [5][12][15][16][17] as well as neuromodulatory [18][19] and antioxidant [20] activities. The mechanisms of bioactivity for these compounds are not yet completely understood with members of this compound class appearing to exert their activity through a number of different modes of action which, for anticancer cell activity, include direct DNA damage [7][8] and inhibition of key cell regulatory enzymes [21].

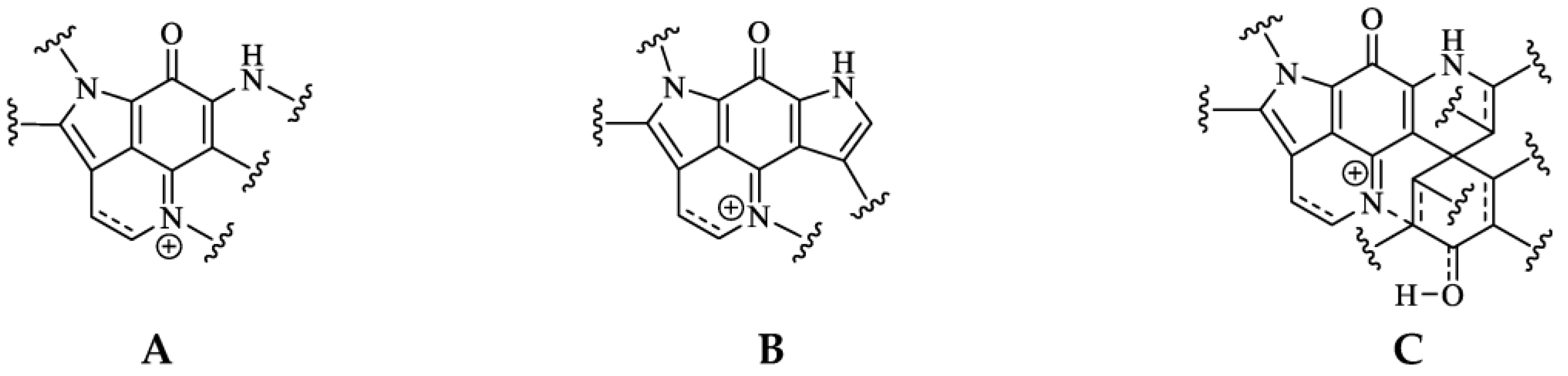

Pyrroloiminoquinone molecular structures are characterized by a condensed tricyclic pyrrolo[4,3,2-de]quinoline core that is also considered the principal pharmacophore of this compound class responsible for their antiproliferative and cytotoxic effects [7][22]. Most compounds of this class can be assigned to one of three major classes exhibiting distinct core structures, namely makaluvamines, bispyrroloiminoquinones and discorhabdins (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Pyrroloiminoquinone structural scaffolds (A)—Makaluvamines, (B)—Bispyrroloiminoquinones, (C)—Discorhabdins.

Pyrroloiminoquinones have been mostly isolated from marine sponges of the order Poecilosclerida, with Latrunculiidae species from temperate and cold-water environments such as New Zealand, South Africa, the Arctic, and Antarctic as well as warm-water Acarnidae species from the Indo-Pacific proving particularly productive sources [2][3][4]. Nevertheless, members of this class of alkaloids have been reported from ascidians [23][24] and simple representatives have also been isolated from cultured myxomycetes [25][26]. Moreover, closely related alkaloids have been reported in hydroids [27][28], terrestrial fungi [29][30][31][32] and marine actinobacteria [33][34]. This wide geographical and phylogenetic distribution of pyrroloiminoquinone producers, as well as the production of related compounds by bacteria raises the question of microbial involvement in their biosynthesis within marine invertebrates.

2. Structures and Host Distribution of Natural Pyrroloiminoquinones and Related Compounds

2.1. Makaluvamines, Bispyrroloiminoquinones and Discorhabdins

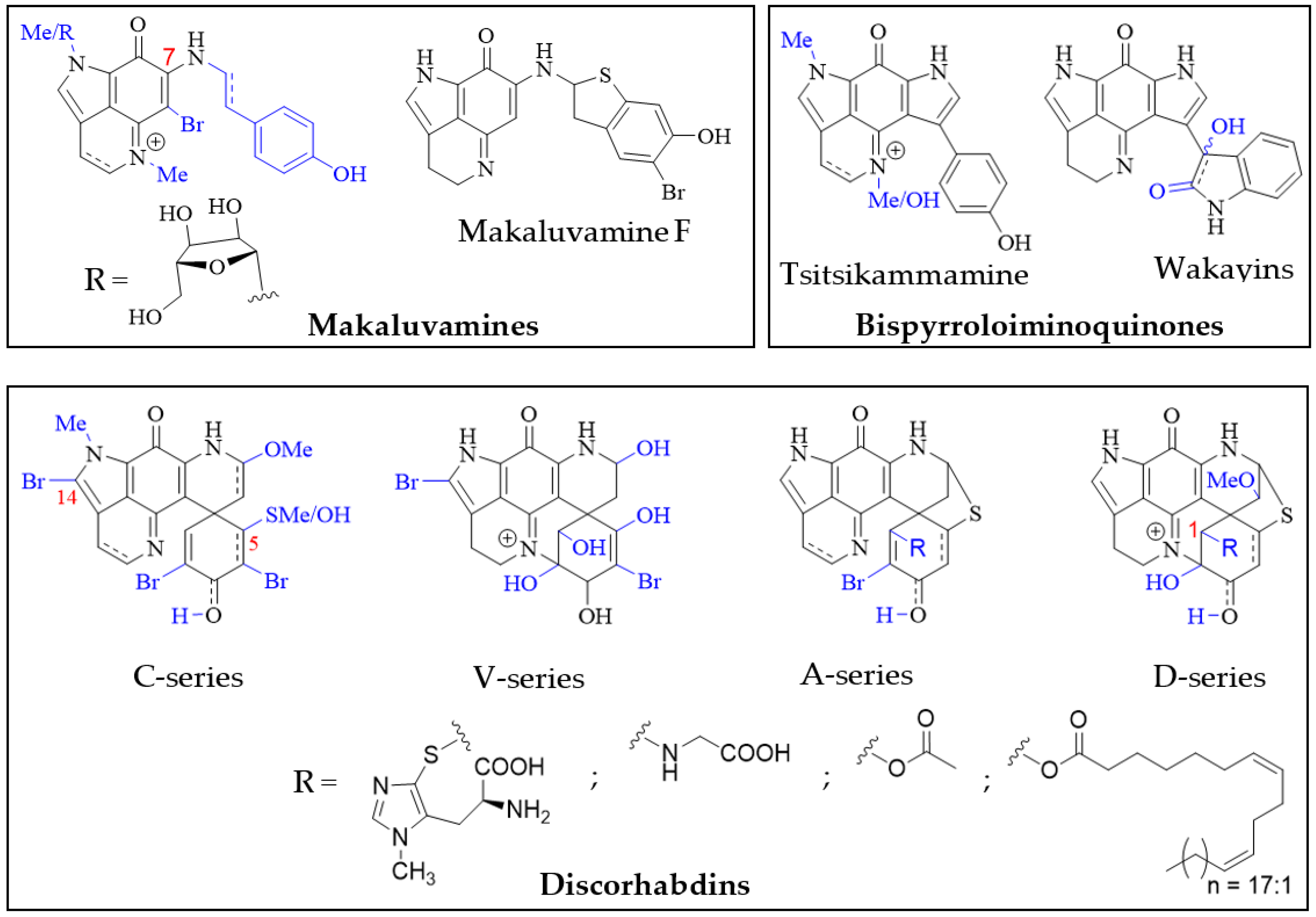

Structurally, the simplest pyrroloiminoquinones are represented by the makaluvamines consisting of the characteristic pyrrolo[4,3,2-de]quinoline core and variable substituents (Figure 2). These include N-methylation of the pyrrole or imine nitrogen, halogenation at C-6, Δ3,4-desaturation and alkylation of N-7 with phenylethyl based side chains. Notable exceptions are makaluvamine O and makaluvamine W and the broad use of the term ‘makaluvamine’ excludes these two structures. Makaluvamines were first reported in 1993 in the sponge Zyzzya fuliginosa collected near the Makaluva Islands, Fiji [7] and since then, have most routinely been isolated from Pacific and Indo-Pacific warm-water sponges of the genus Zyzzya (family Acarnidae) [8][10][11][20][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44]. Makaluvamines have also been isolated from latrunculid sponge species collected off South Africa [22][45][46], the Korean peninsula [16], New Zealand [47] and Australia [21]. Interestingly, simple makaluvamines bearing either no substituents or only exhibiting N-methylation have been purified from cultured myxomycetes, Didymium iridis and Didymium bahiense, isolated from Japanese forest litter samples [25][26]. Makaluvamines are thought to be the biosynthetic precursors to more complex pyrroloiminoquinones and the sulfur-containing makaluvamine F may represent a precursor to sulfur-containing discorhabdins [47].

Figure 2. Main pyrroloiminoquinone classes. Variable substituents encompassing all known compound class members are shown in blue.

Bispyrroloiminoquinones are relatively rare pyrroloiminoquinones containing a characteristic pyrrolo[4,3,2-de]pyrrolo[2,3-h]quinoline core and, depending on the nature of the side-chain, they can be classed as either tsitsikammamines or wakayins (Figure 2). Tsitsikammamines have been reported in the South African marine sponges Tsitsikamma favus and Tsitsikamma nguni [15][22][46][48][49], an Australian Zyzzya sp. [42], Tongan Strongylodesma tongaensis [50] as well as Antarctic Latrunculia biformis [51]. Wakayins (wakayin and 16-hydroxy-17-oxyindolewakayin) on the other hand, have only ever been found in ascidians of the genus Clavelina collected in Micronesia (Wakaya Islands) [23] and Thailand [24].

Pyrroloiminoquinones comprising a pyrido[2,3-h]pyrrolo[4,3,2-de]quinoline core with an additional spiro-fused cyclohexanone/-ol or cyclohexadienone/-ol moiety are known as discorhabdins (Figure 2), some of which are historically also referred to as epinardins or prianosins [52][53][54]. Members of this structurally complex and diverse class of pyrroloiminoquinones are known for particularly potent bioactivities and have attracted significant interest from natural product, medicinal and synthetic chemists alike [5][6][7][9][12][14][15][16][18][21][22][51][55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66][67][68][69][70][71][72][73][74][75]. In contrast to makaluvamines and bispyrroloiminoquinones, discorhabdins have been exclusively found in demosponges, mostly belonging to the family Latrunculiidae. While they all share a characteristic spiro-arrangement flanking the pyrroloiminoquinone core, most known discorhabdins can be divided into distinct structural sub-classes: First, the often multi-brominated, pentacyclic discorhabdins of the C-series and analogous hexacyclic discorhabdins of the V-series exhibiting N(18)-C(2) ring closure and, second, the hexacyclic discorhabdins of the A-series with a bridging sulfur atom connecting C-5 and C-8 and analogous heptacyclic discorhabdins of the D-series displaying N(18)-C(2) ring closure. Some sponges, such as those of genus Tsitsikamma [15][22][46][49], produce only C- and V-series discorhabdins, while the presence of A- and D-series discorhabdins is often accompanied by discorhabdins of the former classes. C-14 bromination also appears to be particular to Tsitsikamma sponges [15][22][46][49] and may represent a chemotaxonomic distinction, while C-5 thiomethylation has only been observed in isolates from a single Caribbean deep-water Strongylodesma purpureus sponge [76] (reassigned from Batzella [77]). A- and D-series discorhabdins often exhibit substitution at C-1 with substituents such as ovothiol, glycine and alkyl esters [22][66][68][72], possibly as a result of increased electrophilic reactivity of the parent compounds [70]. Furthermore, A- and D-series discorhabdins are chiral and enantiomers of opposite parity have been isolated from the same Latrunculia species collected in different locations [65]. To date, all evidence available for comparison suggests that enantiomeric parity does not significantly affect biological activity [65][72].

2.2. Unusual Pyrroloiminoquinones and Related Pyrroloquinolines from Marine Sponges

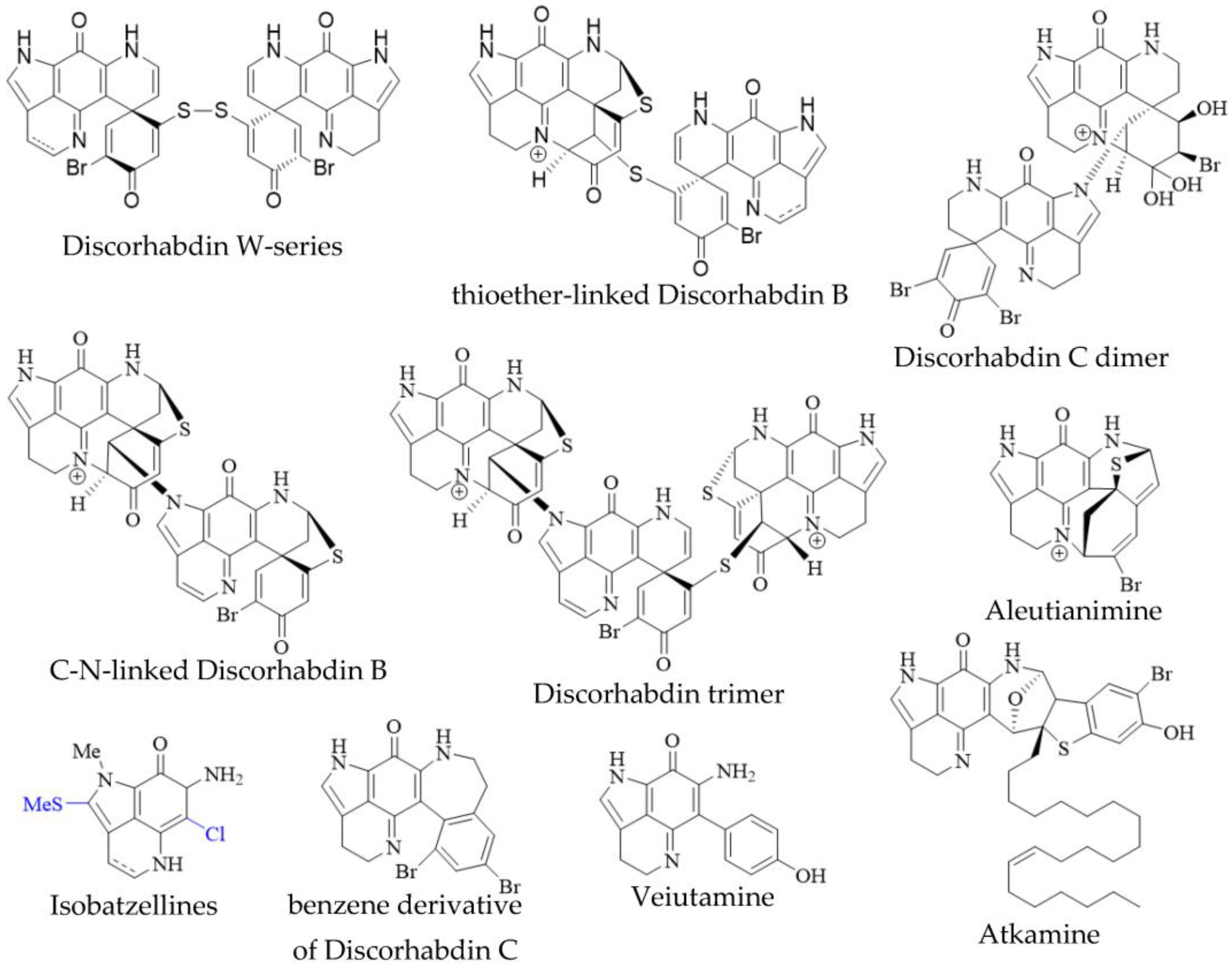

In addition to the monomeric discorhabdins discussed above, several dimeric and trimeric discorhabdins have been isolated from sponges of the genus Latrunculia (Figure 3). These comprise W-series discorhabdins characterized by a disulfide bridge linking two discorhabdin monomers [64][66], thioether-linked discorhabdin dimers [70][74], a C-N-linked discorhabdin C dimer [73], a C-N-linked discorhabdin B dimer as well as a discorhabdin trimer [75]. The saturated discorhabdin W dimer and its monomers have been shown to be interconvertible through reductive cleavage and subsequent UV-irradiation [64], whereas thioether-linked discorhabdin dimers were first discovered as a major degradation product of monomeric discorhabdin stored at −20 °C for a fortnight [70]. Such non-enzymatic dimerization together with the observations that discorhabdins have been shown to be prone to nucleophilic attack at C-1 [70][73] suggest that at least sulfur-bridged discorhabdin dimers may be generated non-enzymatically in situ [73]. Furthermore, LC-MS/MS-driven molecular networking has provided evidence for numerous discorhabdin di- and trimers, some even incorporating makaluvamines, alongside monomeric A- and D-series discorhabdins in extracts of subantarctic Latrunculia apicalis and South African Cyclacanthia bellae [49].

Figure 3. Unusual pyrroloiminoquinones from marine sponges. Variable substituents are shown in blue.

Alike to oligomeric discorhabdins exemplifying a special case of discorhabdin structures, isobatzellines are makaluvamine-like structures that are distinguished by thiomethylation at C-2 or chlorination at C-6 and can thus be regarded as a subgroup of makaluvamines (Figure 3). Isobatzellines exhibiting thiomethylation have been exclusively reported in a Grand Bahaman Strongylodesma nigra specimen [13] (reassigned from Batzella [77]), while those only containing chlorine substituents have also been purified from extracts of Australian and Indopacific Zyzzya sponges [8][11]. Furthermore, two exotic pyrroloiminoquinones, atkamine and aleutianimine (Figure 3), have been isolated from Alaskan Latrunculia sp. [78] and Latrunculia austini [79], respectively. The structure and stereochemistry of atkamine were secured through chemical degradation, as well as comparison of experimental and TDDFT-simulated ECD spectra. Using a similar toolset incorporating DFT-simulated NMR spectra, the same group verified the structure of aleutianimine, providing a compelling example of the usefulness of computational approaches in natural product structure elucidation. Other unusual pyrroloiminoquinones are represented by the benzene derivative of discorhabdin C, isolated alongside various discorhabdins from an Alaskan deep-water Latrunculia sp. [12]. The same compound has been afforded semi-synthetically through dienol-benzene rearrangement [14] and is therefore considered to likely be an isolation artifact [12]. Veiutamine was isolated as a minor secondary metabolite alongside several common pyrroloiminoquinones from Fijian Z. fuliginosa and showed potent in vitro cytotoxicity in a panel of 25 cancer cell lines [80]. Veiutamine exhibits an unusual phenol-substituent directly bound to the pyrroloiminoquinone core and is to date the only known pyrroloiminoquinone with a C-6 p-oxy benzyl substituent.

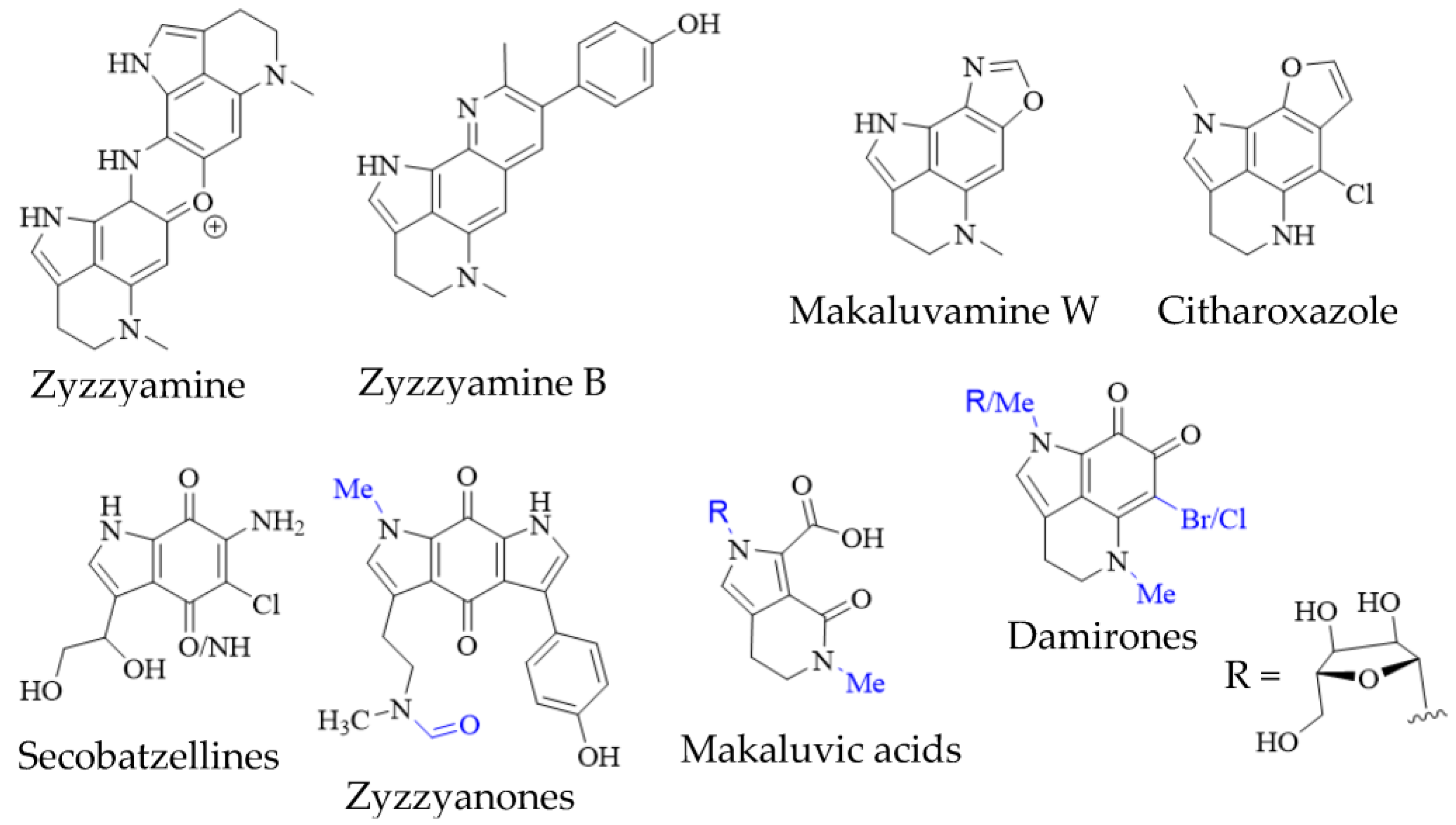

In addition to true pyrroloiminoquinones, several closely related natural products have been isolated from marine sponges, often as minor secondary metabolites alongside makaluvamines, discorhabdins and tsitsikammamines (Figure 4). They include the secobatzellines from a Caribbean Strongylodesma sp. sponge [19] (reassigned from Batzella [81]); zyzzyanones from Australian Z. fuliginosa [42][82]; makaluvic acids from Micronesian Z. fuliginosa [37] and South African Strongylodesma aliwaliensis [83]; the oxazole-containing makaluvamine W from Tongan Strongylodesma tongaensis [50]; the structurally related citharoxazole from Mediterranean Latrunculia citharistae [84] and zyzzyamines from Papua New Guinean Z. fuliginosa [85].

Figure 4. Pyrroloiminoquinone-related marine natural products from sponges. Variable substituents are shown in blue.

Pyrroloiminoquinone isolations commonly result in the recovery of ortho-quinone analogs of makaluvamines, named damirones [86] (Figure 4; some analogs are referred to as batzellines [87] and this structural archetype also encompasses makaluvamine O). As a result, such pyrrolo-ortho-quinones have been isolated from various makaluvamine- and isobatzelline-producing marine sponges including C. bellae (previously Latrunculia bellae [22][88]), S. aliwaliensis [45], Spongosorites sp. [67], Smenospongia aurea [89][90], Zyzzya spp. [7][8][36][38][39][42][43] and T. favus [46], in addition to the myxomycete D. iridis [26]. These compounds generally show greatly decreased cytotoxicity compared to e.g., makaluvamines that contain a pyrroloiminoquinone core [7][22]. Their formation from makaluvamines has been shown to be possible through, alkaline hydrolysis, lyophilization [91] and UV irradiation [92]. This, together with the fact that they in most cases have been isolated alongside makaluvamines, suggests that they may arise simply as degradation products. However, it can currently not be excluded that they may occupy a functional role in pyrroloiminoquinone biosynthesis.

2.3. Pyrroloiminoquinones and Related Pyrroloquinolines from Hydroids, Bacteria and Fungi

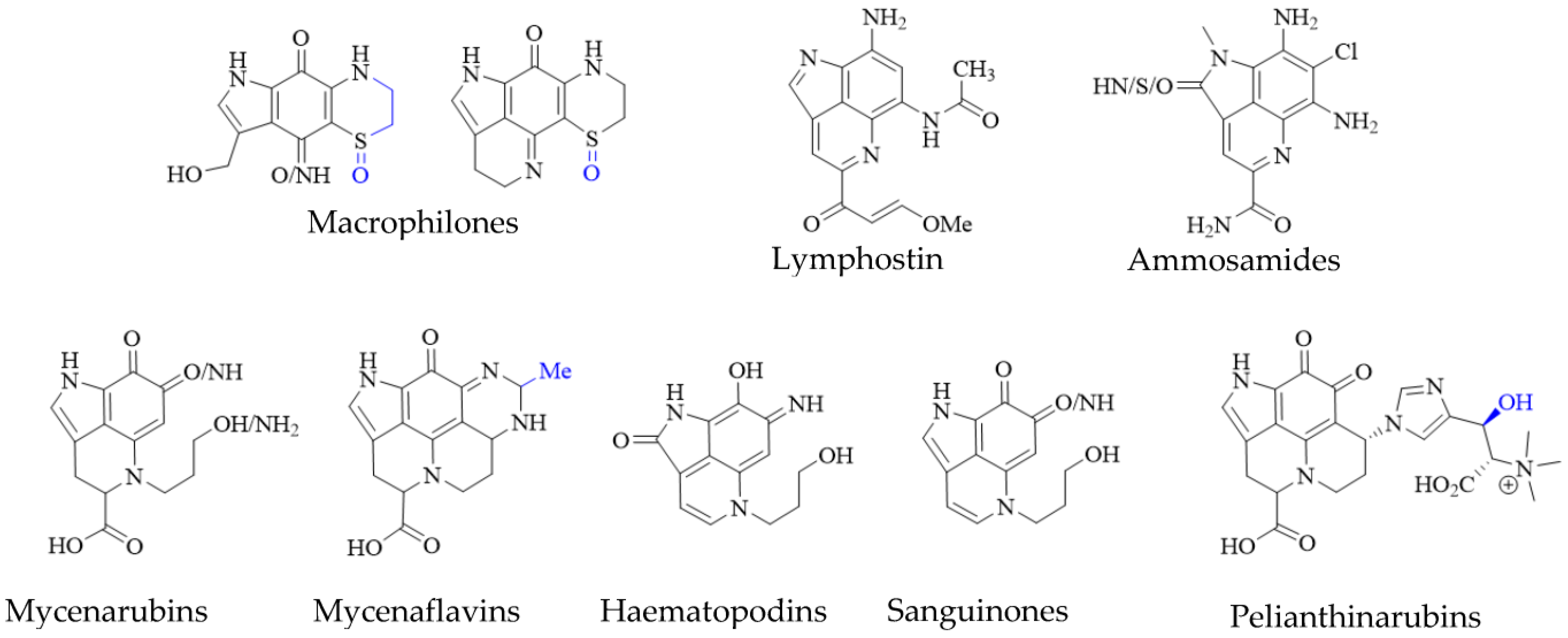

Pyrroloiminoquinone-related compounds have been isolated from several organisms unrelated to marine sponges or ascidians and this occurrence may hold important information to aid the identification of biosynthetic gene clusters or possibly even microbial symbionts responsible for or involved in pyrroloiminoquinone biosynthesis. Such organisms include the Australian marine hydroid Macrorynchia philippina which contains several cytotoxic macrophilones [27][28]. Some of these, exhibit a fully formed pyrroloiminoquinone core and have been shown to inhibit the conjugation of SUMO peptides to target proteins, eliciting greatly decreased levels of proteins involved in ERK signaling, while also exhibiting selective cytotoxicity in the NCI-60 anticancer panel [27][28]. In addition, related pyrroloquinoline alkaloids such as the lymphocyte kinase-inhibiting lymphostin [33] and the selectively cytotoxic ammosamides [34] are produced by marine-derived actinomycetes, Salinispora sp. and Streptomyces sp., respectively (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Pyrroloiminoquinone-related natural products from marine hydroids, marine soil-derived bacteria, and terrestrial fungi. Variable substituents are shown in blue.

While the vast majority of pyrroloiminoquinone structures have been reported from marine sources, terrestrial fungi of the genus Mycena have been shown to produce a range of pigments with clear structural relation to pyrroloiminoquinones (Figure 5). These comprise mycenarubins, mycenaflavins, haematopodins [30][32], sanguinones [29] and pelianthinarubins [31]. Some mycenaflavins have shown cytotoxic activity, while haematopodins and mycenarubins have been reported to exert antibiotic activity against soil bacteria [32]; however, compared with marine pyrroloiminoquinones, the biological activity of these fungal pyrroloquinolines has not been extensively investigated to date.

References

- Urban, S.; Hickford, S.J.H.; Blunt, J.W.; Munro, M.H.G. Bioactive marine alkaloids. Curr. Org. Chem. 2000, 4, 765–807.

- Antunes, E.M.; Copp, B.R.; Davies-Coleman, M.T.; Samaai, T. Pyrroloiminoquinone and related metabolites from marine sponges. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2005, 22, 62–72.

- Hu, J.; Fan, H.; Xiong, J.; Wu, S. Discorhabdins and pyrroloiminoquinone-related alkaloids. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 5465–5491.

- Li, F.; Kelly, M.; Tasdemir, D. Chemistry, Chemotaxonomy and Biological Activity of the Latrunculid Sponges (Order Poecilosclerida, Family Latrunculiidae). Mar. drugs 2021, 19, 27.

- Perry, N.B.; Blunt, J.W.; Munro, M.H.G. Cytotoxic pigments from New Zealand sponges of the genus Latrunculia: Discorhabdins A, B and C. Tetrahedron 1988, 44, 1727–1734.

- Perry, N.B.; Blunt, J.W.; Munro, M.H.G. Discorhabdin D, an Antitumor Alkaloid from the Sponges Latrunculia brevis and Prianos sp. J. Org. Chem. 1988, 53, 4127–4128.

- Radisky, D.C.; Radisky, E.S.; Barrows, L.R.; Copp, B.R.; Kramer, R.A.; Ireland, C.M. Novel cytotoxic topoisomerase II inhibiting pyrroloiminoquinones from Fijian sponges of the genus Zyzzya. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 1632–1638.

- Dijoux, M.-G.; Schnabel, P.C.; Hallock, Y.F.; Boswell, J.L.; Johnson, T.R.; Wilson, J.A.; Ireland, C.M.; van Soest, R.; Boyd, M.R.; Barrows, L.R.; et al. Antitumor activity and distribution of pyrroloiminoquinones in the sponge genus Zyzzya. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005, 13, 6035–6044.

- Harris, E.M.; Strope, J.D.; Beedie, S.L.; Huang, P.A.; Goey, A.K.L.; Cook, K.M.; Schofield, C.J.; Chau, C.H.; Cadelis, M.M.; Copp, B.R.; et al. Preclinical evaluation of discorhabdins in antiangiogenic and antitumor models. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 241.

- Davis, R.A.; Buchanan, M.S.; Duffy, S.; Avery, V.M.; Charman, S.A.; Charman, W.N.; White, K.L.; Shackleford, D.M.; Edstein, M.D.; Andrews, K.T.; et al. Antimalarial activity of pyrroloiminoquinones from the Australian marine sponge Zyzzya sp. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 5851–5858.

- Chang, L.C.; Otero-Quintero, S.; Hooper, J.N.A.; Bewley, C.A. Batzelline D and Isobatzelline E from the Indopacific Sponge Zyzzya fuliginosa. J. Nat. Prod. 2002, 65, 776–778.

- Na, M.; Ding, Y.; Wang, B.; Tekwani, B.L.; Schinazi, R.F.; Franzblau, S.; Kelly, M.; Stone, R.; Li, X.-C.; Ferreira, D.; et al. Anti-infective Discorhabdins from a Deep-Water Alaskan Sponge of the Genus Latrunculia. J. Nat. Prod. 2010, 73, 383–387.

- Sun, H.H.; Sakemi, S.; Burres, N.; McCarthy, P. Isobatzelline A, B, C and D. Cytotoxic and antifungal pyrroloquinoline alkaloids from the marine sponge Batzella sp. J. Org. Chem. 1990, 55, 4964–4966.

- Copp, B.R.; Fulton, K.F.; Perry, N.B.; Blunt, J.W.; Munri, M.H.G. Natural and Synthetic Derivatives of Discorhabdin C, a Cytotoxic Pigment from the New Zealand Sponge Latrunculia cf. bocagei. J. Org. Chem. 1994, 59, 8233–8238.

- Hooper, G.J.; Davies-Coleman, M.T.; Kelly-Borges, M.; Coetzee, P.S. New alkaloids from a South African latrunculid sponge. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996, 37, 7135–7138.

- Jeon, J.; Na, Z.; Jung, M.; Lee, H.; Sim, C.J.; Nahm, K.; Oh, K.-B.; Shin, J. Discorhabdins from the Korean marine sponge Sceptrella sp. J. Nat. Prod. 2010, 73, 258–262.

- Crews, P.; Valeriote, F.A.; Lin, S.; McCauley, E.P.; Lorig-Roach, N.; Tenney, K. Pyrroloquinolin Compounds and Methods of Using Same. U.S. patent US 11,020,488, 1 June 2021.

- Botić, T.; Defant, A.; Zanini, P.; Žužek, M.C.; Frangež, R.; Janussen, D.; Kersken, D.; Knez, Ž.; Mancini, I.; Sepĉić, K. Discorhabdin alkaloids from Antarctic Latrunculia spp. sponges as a new class of cholinesterase inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 136, 294–304.

- Gunasekera, S.P.; McCarthy, P.J.; Longley, R.E.; Pomponi, S.A.; Wright, A.E. Secobatzellines A and B, Two New Enzyme Inhibitors from a Deep-Water Caribbean Sponge of the Genus Batzella. J. Nat. Prod. 1999, 62, 1208–1211.

- Alonso, E.; Alvariño, R.; Leirós, M.; Tabudravu, J.N.; Feussner, K.; Dam, M.A.; Rateb, M.E.; Jaspars, M.; Botana, L.M. Evaluation of the antioxidant activity of the marine pyrroloiminoquinone makaluvamines. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 197.

- Goey, A.K.L.; Chau, C.H.; Sissung, T.M.; Cook, K.M.; Venzon, D.J.; Castro, A.; Ransom, T.R.; Henrich, C.J.; McKee, T.C.; McMahon, J.B.; et al. Screening and biological effects of marine pyrroloiminoquinone alkaloids: Potential inhibitors of the HIF-1α/p300 interaction. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 1267–1275.

- Antunes, E.M.; Beukes, D.R.; Kelly, M.; Samaai, T.; Barrows, L.R.; Marshall, K.M.; Sincich, C.; Davies-Coleman, M.T. Cytotoxic pyrroloiminoquinones from four new species of South African latrunculid sponges. J. Nat. Prod. 2004, 67, 1268–1276.

- Copp, B.R.; Ireland, C.M. Wakayin: A Novel Cytotoxic Pyrroloiminoquinone Alkaloid from the Ascidian Clavelina Species. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 4596–4597.

- Grkovic, T.; Ruchirawat, S.; Kittakoop, P.; Grothaus, P.G.; Evans, J.R.; Britt, J.R.; Newman, D.J.; Mahidol, C.; O’Keefe, B.R. A New Bispyrroloiminoquinone Alkaloid From a Thai Collection of Clavelina sp. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2021, 10, 1647–1649.

- Ishibashi, M.; Iwasaki, T.; Imai, S.; Sakamoto, S.; Yamaguchi, K.; Ito, A. Laboratory culture of the myxomycetes: Formation of fruiting bodies of Didymium bahiense and its plasmodial production of makaluvamine A. J. Nat. Prod. 2001, 64, 108–110.

- Nakatani, S.; Kiyota, M.; Matsumoto, J.; Ishibashi, M. Pyrroloiminoquinone pigments from Didymium iridis. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2005, 33, 323–325.

- Zlotkowski, K.; Hewitt, W.M.; Yan, P.; Bokesch, H.R.; Peach, M.L.; Nicklaus, M.C.; O’Keefe, B.R.; McMahon, J.B.; Gustafson, K.R.; Schneekloth, J.S., Jr. Macrophilone A: Structure Elucidation, Total Synthesis, and Functional Evaluation of a Biologically Active Iminoquinone from the Marine Hydroid Macrorhynchia philippina. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 1726–1729.

- Yan, P.; Ritt, D.A.; Zlotkowski, K.; Bokesch, H.R.; Reinhold, W.C.; Schneekloth, J.S., Jr.; Morrison, D.K.; Gustafson, K.R. Macrophilones from the Marine Hydroid Macrorhynchia philippina Can Inhibit ERK Cascade Signaling. J. Nat. Prod. 2018, 81, 1666–1672.

- Peters, S.; Spiteller, P. Sanguinones A and B, Blue Pyrroloquinoline Alkaloids from the Fruiting Bodies of the Mushroom Mycena sanguinolenta. J. Nat. Prod. 2007, 70, 1274–1277.

- Peters, S.; Jaeger, R.J.R.; Spiteller, P. Red Pyrroloquinoline Alkaloids from the Mushroom Mycena haematopus. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 2008, 319–323.

- Pulte, A.; Wagner, S.; Kogler, H.; Spiteller, P. Pelianthinarubins A and B, Red Pyrroloquinoline Alkaloids from the Fruiting Bodies of the Mushroom Mycena pelianthina. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 873–878.

- Lohmann, J.S.; Wagner, S.; von Nussbaum, M.; Pulte, A.; Steglich, W.; Spiteller, P. Mycenaflavin A, B, C and D: Pyrroloquinoline Alkaloids from the Fruiting Bodies of the Mushroom Mycena haematopus. Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 8609–8614.

- Nagata, H.; Ochiai, K.; Aotani, Y.; Ando, K.; Yoshida, M.; Takahashi, I.; Tamaoki, T. Lymphostin (LK6-A), a Novel Immunosuppressant from Streptomyces sp. KY11783: Taxonomy of the Producing Organism, Fermentation, Isolation, and Biological Activities. J. Antibiot. 1997, 50, 537–542.

- Hughes, C.C.; MacMillan, J.B.; Gaudencio, S.P.; Jensen, P.R.; Fenical, W. The ammosamides: Structures of cell cycle modulators from a marine-derived Streptomyces species. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 725–727.

- Carney, J.R.; Scheuer, P.J.; Kelly-Borges, M. Makaluvamine G, a cytotoxic pigment from an Indonesian sponge Histodermella sp. Tetrahedron 1993, 49, 8483–8486.

- Schmidt, E.W.; Harper, M.K.; Faulkner, D.J. Makaluvamines H-M and damirone C from the Pohnpeian sponge Zyzzya fuliginosa. J. Nat. Prod. 1995, 58, 1861–1867.

- Fu, X.; Ng, P.-L.; Schmitz, F.J.; Hossain, M.B.; van der Helm, D.; Kelly-Borges, M. Makaluvic acids A and B: Novel Alkaloids from the Marine Sponge Zyzzya fuliginosus. J. Nat. Prod. 1996, 59, 1104–1106.

- Venables, D.A.; Concepciόn, G.P.; Matsumoto, S.S.; Barrows, L.R.; Ireland, C.M. Makaluvamine N: A new pyrroloiminoquinone from Zyzzya fuliginosa. J. Nat. Prod. 1997, 60, 408–410.

- Popov, A.M.; Utkina, N.K. Pyrroloquinoline alkaloids from Zyzzya sp. sea sponges: Isolation and antitumor activity characterization. Pharm. Chem. J. 1998, 32, 298–300.

- Tasdemir, D.; Mangalindan, G.C.; Concepción, G.P.; Harper, M.K.; Ireland, C.M. 3,7-Dimethylguanine, a New Purine from a Philippine Sponge Zyzzya fuliginosa. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2001, 49, 1628–1630.

- Casapullo, A.; Cutignano, A.; Bruno, I.; Bifulco, G.; Debitus, C.; Gomez-Paloma, L.; Riccio, R. Makaluvamine P, a New Cytotoxic Pyrroloiminoquinone from Zyzzya cf. fuliginosa. J. Nat. Prod. 2001, 64, 1354–1356.

- Utkina, N.K.; Makarchenko, A.E.; Denisenko, V.A.; Dmitrenok, P.S. Zyzzyanone A, a novel pyrroloindole alkaloid from the Australian marine sponge Zyzzya fuliginosa. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 7491–7494.

- Lin, S.; McCauley, E.P.; Lorig-Roach, N.; Tenney, K.; Naphen, C.N.; Yang, A.; Johnson, T.A.; Hernandez, T.; Rattan, R.; Valeriote, F.A.; et al. Another look at pyrroloiminoquinone alkaloids-perspectives on their therapeutic potential from known structures and semisynthetic analogues. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 98.

- Kudryavtsev, D.S.; Spirova, E.N.; Shelukhina, I.V.; Son, L.V.; Makarova, Y.V.; Utkina, N.K.; Kasheverov, I.E.; Tsetlin, V.I. Makaluvamine G from the Marine Sponge Zyzzia fuliginosa Inhibits Muscle nAChR by Binding at the Orthosteric and Allosteric Sites. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 109.

- Keyzers, R.A.; Samaai, T.; Davies-Coleman, M.T. Novel purroloquinoline ribosides from the South African latrunculid sponge Strongylodesma aliwaliensis. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 9415–9418.

- Kalinski, J.-C.J.; Waterworth, S.C.; Siwe Noundou, X.; Jiwaji, M.; Parker-Nance, S.; Krause, R.W.M.; McPhail, K.L.; Dorrington, R.A. Molecular Networking Reveals Two Distinct Chemotypes in Pyrroloiminoquinone-Producing Tsitsikamma favus Sponges. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 60.

- Lill, R.E.; Major, D.A.; Blunt, J.W.; Munro, M.H.G.; Battershill, C.N.; McLean, M.G.; Baxter, R.L. Studies on the biosynthesis of discorhabdin B in the New Zealand sponge Latrunculia sp. J. Nat. Prod. 1995, 58, 306–311.

- Parker-Nance, S.; Hilliar, S.; Waterworth, S.; Walmsley, T.; Dorrington, R. New species in the sponge genus Tsitsikamma (Poecilosclerida, Latrunculiidae) from South Africa. Zookeys 2019, 126, 101–126.

- Kalinski, J.C.J.; Krause, R.W.; Parker-Nance, S.; Waterworth, S.C.; Dorrington, R.A. Unlocking the diversity of pyrroloiminoquinones produced by Latrunculid sponge species. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 68.

- Taufa, T.; Gordon, R.M.A.; Ali Hashmi, M.; Hira, K.; Miller, J.H.; Lein, M.; Fromont, J.; Northcote, P.T.; Keyzers, R.A. Pyrroloquinoline derivatives from a Tongan specimen of the marine sponge Strongylodesma tongaensis. Tetrahedron Lett. 2019, 60, 1825–1829.

- Li, F.; Pfeifer, C.; Pérez-Victoria, I.; Tasdemir, D. Targeted isolation of tsitsikammamines from the Antarctic deep-sea sponge Latrunculia biformis by molecular networking and anticancer activity. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 268.

- D’Ambrosio, M.; Guerreiro, A.; Chiasera, G.; Pietra, F. Epinardins A-D, new pyrroloiminoquinone alkaloids of undetermined deep-water green demosponges from pre-Antarctic Indian Ocean. Tetrahedron 1996, 26, 8899–8906.

- Kobayashi, J.; Cheng, J.-F.; Ishibashi, M.; Nakamura, H.; Ohizumi, Y.; Hirata, Y.; Sasaki, T.; Lu, H.; Clardy, J. Prianosin A, A Novel Antileukemic Alkaloid from the Okinawan Marine Sponge Prianos melanos. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987, 28, 4939–4942.

- Cheng, J.-F.; Ohizumi, Y.; Wälchli, M.R.; Nakamura, H.; Hirata, Y.; Sasaki, T.; Kobayashi, J. Prianosins B,C, and D, novel sulfur-containing alkaloids with potent antineoplastic activity from the Okinawan marine sponge Prianos melanos. J. Org. Chem. 1988, 53, 4621–4624.

- Harayama, Y.; Kita, Y. Pyrroloiminoquinone Alkaloids: Discorhabdins and Makaluvamines. Curr. Org. Chem. 2005, 9, 1567–1588.

- Wada, Y.; Fujioka, H.; Kita, Y. Synthesis of the Marine Pyrroloiminoquinone Alkaloids, Discorhabdins. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 1394–1416.

- Smith, M.W.; Falk, I.D.; Ikemoto, H.; Burns, N.Z. A convenient C–H functionalization platform for pyrroloiminoquinone alkaloid synthesis. Tetrahedron 2019, 75, 3366–3370.

- Perry, N.B.; Blunt, J.W.; McCombs, J.D.; Munro, M.H.G. Discorhabdin C, a highly cytotoxic pigment from a sponge of the genus Latrunculia. J. Org. Chem. 1986, 51, 5476–5478.

- Yang, A.; Baker, B.J.; Grimwade, J.; Leonard, A.; McClintock, J.B. Discorhabdin alkaloids from the Antarctic sponge Latrunculia apicalis. J. Nat. Prod. 1995, 58, 1596–1599.

- Dijoux, M.-G.; Gamble, W.R.; Hallock, Y.F.; Cardellina, J.H., II; van Soest, R.; Boyd, M.R. A New Discorhabdin from Two Sponge Genera. J. Nat. Prod. 1999, 62, 636–637.

- Gunasekera, S.P.; McCarthy, P.J.; Longley, R.E.; Pomponi, S.A.; Wright, A.E.; Lobkovsky, E.; Clardy, J.J. Discorhabdin P, a new enzyme inhibitor from deep-water Caribbean sponge of the genus Batzella. J. Nat. Prod. 1999, 62, 173–175.

- Ford, J.; Capon, R.J. Disocrhabdin R: A new antibacterial pyrroloiminoquinone from two latrunculid marine sponges, Latrunculia sp. and Negombata sp. J. Nat. Prod. 2000, 63, 1527–1528.

- Reyes, F.; Martín, R.; Rueda, A.; Fernández, R.; Montalvo, D.; Gómez, C.; Sánchez-Puelles, J.M. Discorhabdins I and L, Cytotoxic Alkaloids from the Sponge Latrunculia brevis. J. Nat. Prod. 2004, 67, 463–465.

- Lang, G.; Pinkert, A.; Blunt, J.W.; Munro, M.H.G. Discorhabdin W, the First Dimeric Discorhabdin. J. Nat. Prod. 2005, 68, 1796–1798.

- Grkovic, T.; Ding, Y.; Li, X.-C.; Webb, V.L.; Ferreira, D.; Copp, B.R. Enantiomeric Discorhabdin Alkaloids and Establishment of Their Absolute Configurations Using Theoretical Calculations of Electronic Circular Dichroism Spectra. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 9133–9136.

- Grkovic, T.; Copp, B.R. New natural products in the discorhabdin A- and B-series from New Zealand-sourced Latrunculia spp. sponges. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 6335–6340.

- El-Naggar, M.; Capon, R.J. Discorhabdins Revisited: Cytotoxic Alkaloids from Southern Australian Marine Sponges of the Genera Higginsia and Spongosorites. J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72, 460–464.

- Grkovic, T.; Pearce, A.N.; Munro, M.H.G.; Blunt, J.W.; Davies-Coleman, M.T.; Copp, B.R. Isolation and Characterization of Diastereomers of Discorhabdins H and K and Assignment of Absolute Configuration to Discorhabdins D, N, Q, S, T, and U. J. Nat. Prod. 2010, 73, 1686–1693.

- Makar’eva, T.N.; Krasokhin, V.B.; Guzii, A.G.; Stonik, V.A. Strong ethanol solvate of discorhabdin A isolated from the far-east sponge Latruculia oparinae. Chem. Nat. Comp. 2010, 46, 152–153.

- Lam, C.F.C.; Grkovic, T.; Pearce, N.A.; Copp, B.R. Investigation of the electrophilic reactivity of the cytotoxic marine alkaloid discorhabdin B. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 3092.

- Lam, C.F.C.; Cadelis, M.M.; Copp, B.R. Exploration of the influence of spiro-dienone moiety on biological activity of cytotoxic marine alkaloid discorhabdin P. Tetrahedron 2017, 73, 4779–4785.

- Li, F.; Peifer, C.; Janussen, D.; Tasdemir, D. New Discorhabdin Alkaloids from the Antarctic Deep-Sea Sponge Latrunculia biformis. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 439.

- Lam, C.F.C.; Cadelis, M.M.; Copp, B.R. Exploration of the Electrophilic Reactiovity of the Cytotoxic Marine Alkaloid Discorhabdin C and Subsequent Discovery of a New Dimeric C-1/N-13-Linked Discorhabdin Natural Product. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 404.

- Li, F.; Janussen, D.; Tasdemir, D. New Discorhabdin B Dimers with Anticancer Activity from the Antarctic Deep-Sea Sponge Latrunculia biformis. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 107.

- Li, F.; Pandey, P.; Janussen, D.; Chittiboyina, A.G.; Ferreira, D.; Tasdemir, D. Tridiscorhabdin and Didiscorhabdin, the First Discorhabdin Oligomers Linked with a Direct C-N Bridge from the Sponge Latrunculia biformis Collected from the Deep Sea in Antarctica. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 706–713.

- Gunasekera, S.P.; Zuleta, I.A.; Longley, R.E.; Wright, A.E.; Pomponi, S.A. Discorhabdins S, T, and U, New Cytotoxic Pyrroloiminoquinones from a Deep-Water Caribbean Sponge of the Genus Batzella. J. Nat. Prod. 2003, 66, 1615–1617.

- Samaai, T.; Gibbons, M.J.; Kelly, M. A revision of the genus Strongylodesma Lévi (Porifera: Demospongiae: Latrunculiidae) with descriptions of four new species. J. Mar. Biol. Ass. 2009, 89, 1689–1702.

- Zou, Y.; Hamann, M.T. Atkamine: A New Pyrroloiminoquinone Scaffold from the Cold Water Aleutian Islands Latrunculia Sponge. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 1516–1519.

- Zou, Y.; Wang, X.; Sims, J.; Wang, B.; Pandey, P.; Welsh, C.L.; Stone, R.P.; Avery, M.A.; Doerksen, R.J.; Ferreira, D.; et al. Computationally Assisted Discovery and Assignment of a Highly Strained and PANC-1 Selective Alkaloid from Alaska’s Deep Ocean. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 4338–4344.

- Venables, D.A.; Barrows, L.R.; Lasotta, P.; Ireland, C.M. Veiutamine. A New Alkaloid from the Fijian Sponge Zyzzya fuliginosa. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 721–722.

- Samaai, T.; Keyzers, R.A.; Davies-Coleman, M.T. A new species of Strongylodesma Levi, 1969 (Porifera; Demospongiae; Poecilosclerida; Latrunculiidae) from Aliwal Shoal on the east coast of South Africa. Zootaxa 2004, 584, 1–11.

- Utkina, N.K.; Makarchenko, A.E.; Denisenko, V.A. Zyzzyanones B-D, Dipyrroloquinones from the Marine Sponge Zyzzya fuliginosa. J. Nat. Prod. 2005, 68, 1424–1427.

- Keyzers, R.A.; Arendse, C.E.; Hendricks, D.T.; Samaai, T.; Davies-Coleman, M.T. Makaluvic Acids from the South African Latrunculid Sponge Strongylodesma aliwaliensis. J. Nat. Prod. 2005, 68, 506–510.

- Genta-Jouve, G.; Francezon, N.; Puissant, A.; Auberger, P.; Vacelet, J.; Pérez, T.; Fontana, A.; Al Mourabit, A.; Thomas, O.P. Structure elucidation of the new citharoxazole from the Mediterranean deep-sea sponge Latrunculia (Biannulata) citharistae. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2011, 49, 533–536.

- McCauley, E.P.; Smith, G.C.; Crews, P. Unraveling Structures Containing Highly Conjugated Pyrroloquinoline Cores That Are Deficient in Diagnostic Proton NMR Signals. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 174–178.

- Stierle, D.B.; Faulkner, D.J. Two New Pyrroloquinoline Alkaloids from the Sponge Damiria sp. J. Nat. Prod. 1991, 54, 1131–1133.

- Sakemi, S.; Sun, H.H.; Jefford, C.W.; Bernardinelli, G. Batzellines A, B and C. Novel pyrroloquinoline alkaloids from the sponge Batzella sp. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989, 19, 2517–2520.

- Samaai, T.; Govender, V.; Kelly, M. Cyclacanthia n.g. (Demospongiae: Poecilosclerida: Latrunculiidae incertea sedis), a new genus of marine sponges from South African waters, and description of two new species. Zootaxa 2004, 725, 1–18.

- Hu, J.; Schetz, J.A.; Kelly, M.; Peng, J.; Ang, K.K.H.; Flotow, H.; Yan Leong, C.; Bee Ng, S.; Buss, A.D.; Wilkins, S.P.; et al. New antiinfective and human 5-HT2 receptor binding natural and semisynthetic compounds from the Jamaican sponge Smenospongia aurea. J. Nat. Prod. 2002, 65, 476–480.

- Tasdemir, D.; Bugni, T.S.; Mangalindan, G.C.; Concepción, G.P.; Harper, M.K.; Ireland, C.M. Cytotoxic Bromoindole Derivatives and Terpenes from the Philippine Marine Sponge Smenospongia sp. Z. Für Nat. C 2002, 57, 914–922.

- Utkina, N.K.; Gerasimenko, A.V.; Popov, D.Y. Transformation of tricyclic makaluvamines from the marine sponge Zyzzya fuliginosa into damirones. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2003, 52, 258–260.

- Makarchenko, A.E.; Utkina, N.K. UV-Stability and UV-Protective Activity of Alkaloids from the Marine Sponge Zyzzya fuliginosa. Chem. Nat. Comp. 2006, 42, 78–81.

More

Information

Subjects:

Chemistry, Medicinal

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.3K

Entry Collection:

Biopharmaceuticals Technology

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

22 Dec 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No