Video Upload Options

File:SierraLeoneHofstra3.1.tiff European colonialism and colonization was the policy or practice of acquiring full or partial political control over other societies and territories, creating a colony, occupying it with settlers, and exploiting it economically. Research suggests, the current conditions of postcolonial countries have roots in colonial actions and policies. For example, colonial policies, such as the type of rule implemented, the nature of investments, and identity of the colonizers, are cited as impacting postcolonial states. Examination of the state-building process, economic development, and cultural norms and mores shows the direct and indirect consequences of colonialism on the postcolonial states.

1. History of Colonisation and Decolonization

The era of European colonialism lasted from the 16th to 19th centuries and involved European powers vastly extending their reach around the globe by establishing colonies in the Americas, Africa, and Asia. The dismantling of European empires following World War II saw the process of decolonization begin in earnest.[1] In 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill jointly released the Atlantic Charter, which broadly outlined the goals of the U.S. and British governments. One of the main clauses of the charter acknowledged the right of all people to choose their own government.[2] The document became the foundation for the United Nations and all of its components were integrated into the UN Charter, giving the organization a mandate to pursue global decolonization.[3] Despite a uniform effort by the United Nations, modern postcolonial states vary widely in terms of political and economic stability.

2. Varieties of Colonialism

Historians generally distinguish two main varieties established by European colonials: settler colonialism, where towns and cities were established with primarily European residents and the amenities of a "Neo-Europe" and exploitation colonialism, purely extractive and exploitative colonies whose primary function was to exploit resources.[4] These frequently overlapped or existed on a spectrum.[5]

2.1. Settler Colonialism

Settler colonialism is a form of colonisation where foreign citizens move into a region and create permanent or temporary settlements called colonies. The creation of settler colonies often resulted in the forced migration of indigenous peoples to less desirable territories through forced migration. This practice is exemplified in the colonies established in the United States , New Zealand, South Africa , Canada , Argentina , and Australia . Native populations frequently suffer population collapse due do contact with new diseases.[6]

The resettlement of indigenous peoples frequently occurs along demographic lines, but the central stimulus for resettlement is access to desirable territory. Regions free of tropical disease with easy access to trade routes were favorable.[7] When Europeans settled in these desirable territories, natives were forced out and regional power was transferred to the colonialists. This type of colonial behavior led to the disruption of local customary practices and the transformation of socioeconomic systems. Ugandan academic Mahmood Mamdani cites "the destruction of communal autonomy, and the defeat and dispersal of tribal populations" as one primary factor in colonial oppression.[5] Europeans justified settler colonialism with the belief that the settlers were more capable of utilizing resources and land than the indigenous populations due to the introduction of modern agricultural practices. As agricultural expansion continued through the territories, native populations were further displaced to clear fertile farmland.[7]

Daron Acemoglu, James A. Robinson, and Simon Johnson theorize that Europeans were more likely to form settler colonies in areas where they would not face high mortality rates due to disease and other exogenous factors.[4] Many settler colonies sought to establish European-like institutions and practices that granted personal freedoms and allowed settlers to become wealthy by engaging in trade.[8] Thus, jury trials, freedom from arbitrary arrest, and electoral representation were implemented to allow settlers rights similar to those enjoyed in Europe.[4] Though these rights were generally not extended to the indigenous people.

2.2. Exploitation Colonialism

Since these colonies were created with the intent to extract resources, colonial powers has no incentive to invest in institutions or infrastructure that did not support their immediate goals of exploitation. Therefore, they established authoritarian regimes in these colonies, which had no limits on state power.[4]

Exploitation colonialism is a form of colonisation where foreign citizens conquer a country in order to control and capitalize on its natural resources and indigenous population. Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson argue, "institutions [established by colonials] did not introduce much protection for private property, nor did they provide checks and balances against government expropriation. In fact, the main purpose of the extractive state was to transfer as much of the resources of the colony to the colonizer, with the minimum amount of investment possible."[4] Since these colonies were created with the intent to extract resources, colonial powers has no incentives to invest in institutions or infrastructure that did not support their immediate goals. Thus, Europeans established authoritarian regimes in these colonies, which had no limits on state power.[4]

The policies and practices carried out by King Leopold II of Belgium in the Congo Basin are an extreme example of exploitation colonialism.[4] E. D. Morel, a British journalist, author, pacifist, and politician, detailed the atrocities in multiple articles and books. Morel believed the Belgian system that eliminated traditional, commercial markets in favor of pure exploitation was the root cause of the injustice in the Congo.[9] Under the "veil of philanthropic motive", King Leopold received the consent of multiple international governments (including the United States , Great Britain, and France ) to assume trusteeship of the vast region in order to support the elimination of the slave trade. Leopold positioned himself as proprietor of an area totaling nearly one million square miles, which was home to nearly 20 million Africans.[10]

After establishing dominance in the Congo Basin, Leopold extracted large quantities of ivory, rubber, and other natural resources. It has been estimated that Leopold made 1.1 billion in today's dollars[11] by employing a variety of exploitative tactics. Soldiers demanded unrealistic quantities of rubber be collected by African villagers, and when these goals were not met, the soldiers held women hostage, beat or killed the men, and burned crops.[12] These and other forced labor practices caused the birth rate to decline as famine and disease spread. All of this was done at very little monetary cost to Belgium. M. Crawford Young, Professor Emeritus of Political Science at the University of Wisconsin–Madison observed, "[the Belgian companies] brought little capital – a mere 8000 pounds ... [to the Congo basin] – and instituted a reign of terror sufficient to provoke an embarrassing public-protest campaign in Britain and the United States at a time when the threshold of toleration for colonial brutality was high."[13]

The system of government implemented in the Congo by Belgium was authoritarian and oppressive. Multiple scholars view the roots of authoritarianism under Mobutu as the result of colonial practices.[14][15]

3. Indirect and Direct Rule of the Colonial Political System

Systems of colonial rule can be broken into the binary classifications of direct and indirect rule. During the era of colonisation, Europeans were faced with the monumental task of administrating the vast colonial territories around the globe. The initial solution to this problem was direct rule,[5] which involves the establishment of a centralized European authority within a territory run by colonial officials. In a system of direct rule, the native population is excluded from all but the lowest level of the colonial government.[16] Mamdani defines direct rule as centralized despotism: a system where natives were not considered citizens.[5] By contrast, indirect rule integrates pre-established local elites and native institutions into the administration of the colonial government.[16] Indirect rule maintains good pre-colonial institutions and fosters development within the local culture.[17] Mamdani classifies indirect rule as “decentralized despotism,” where day-to-day operations were handled by local chiefs, but the true authority rested with the colonial powers.[5]

3.1. Indirect Rule

In certain cases, as in India , the colonial power directed all decisions related to foreign policy and defense, while the indigenous population controlled most aspects of internal administration.[18] This led to autonomous indigenous communities that were under the rule of local tribal chiefs or kings. These chiefs were either drawn from the existing social hierarchy or were newly minted by the colonial authority. In areas under indirect rule, traditional authorities acted as intermediaries for the “despotic” colonial rule,[19] while the colonial government acted as an advisor and only interfered in extreme circumstances.[17] Often, with the support of the colonial authority, natives gained more power under indirect colonial rule than they had in the pre-colonial period.[17] Mamdani points out that indirect rule was the dominant form of colonialism and therefore most who were colonized bore colonial rule that was delivered by their fellow natives.[20]

The purpose of indirect rule was to allow natives to govern their own affairs through “customary law.” In practice though, the native authority decided on and enforced its own unwritten rules with the support of the colonial government. Rather than following the rule of law, local chiefs enjoyed judicial, legislative, executive, and administrative power in addition to legal arbitrariness.[20]

3.2. Direct Rule

In systems of direct rule, Europeans colonial officials oversaw all aspects of governance, while natives were placed in an entirely subordinate role. Unlike indirect rule, the colonial government did not convey orders through local elites, but rather oversaw administration directly. European laws and customs were imported to supplant traditional power structures.[16] Joost van Vollenhoven, Governor-General of French West Africa, 1917-1918, described the role of the traditional chiefs in by saying, “his functions were reduced to that of a mouthpiece for orders emanating from the outside…[The chiefs] have no power of their own of any kind. There are not two authorities in the cercle', the French authority and the native authority; there is only one.”[17] The chiefs were therefore ineffective and not highly regarded by the indigenous population. There were even instances where people under direct colonial rule secretly elected a real chief in order to retain traditional rights and customs.[21]

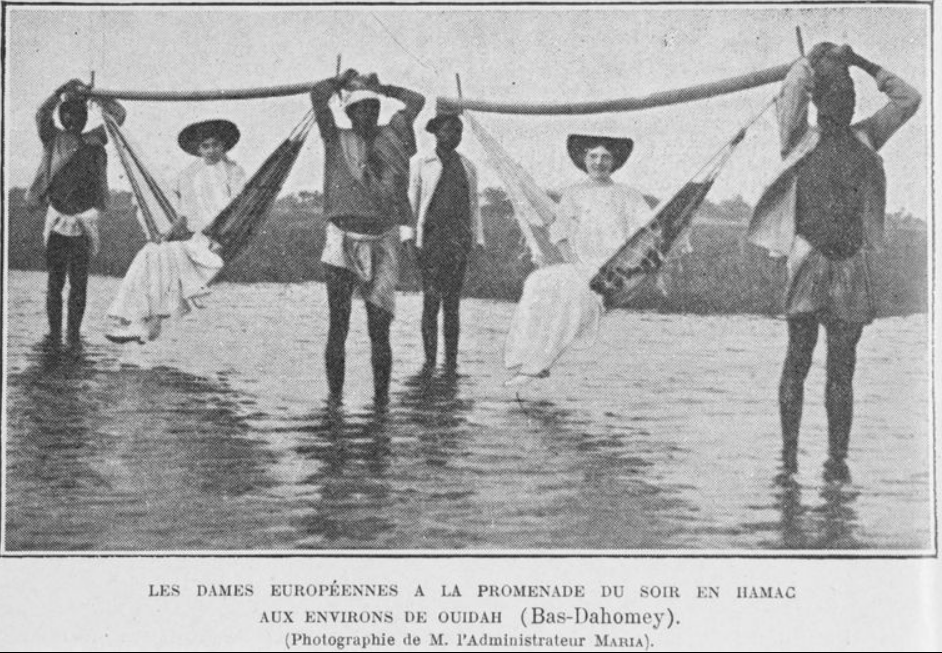

Direct rule deliberately removed traditional power structures in order to implement uniformity across a region. The desire for regional homogeneity was the driving force behind the French colonial doctrine of Assimilation.[22] The French style of colonialism stemmed from the idea that the French Republic was a symbol of universal equality.[23] As part of a civilizing mission, the European principles of equality were translated into legislation abroad. For the French colonies, this mean the enforcement of the French penal code, the right to send a representative to parliament, and imposition of tariff laws as a form of economic assimilation. Requiring natives to assimilate in these and other ways, created an ubiquitous, European-style identity that made no attempt to protect native identities.[24] Indigenous people living in colonized societies were obliged to obey European laws and customs or be deemed “uncivilized” and denied access to any European rights.

3.3. Comparative Outcomes between Indirect and Direct Rule

Both direct and indirect rule have persistent, long term effects on the success of former colonies. Lakshmi Iyer, of Harvard Business School, conducted research to determine the impact type of rule can have on a region, looking at postcolonial India, where both systems were present under British rule. Iyer’s findings suggests that regions which had previously been ruled indirectly were generally better-governed and more capable of establishing effective institutions than areas under direct British rule. In the modern postcolonial period, areas formerly ruled directly by the British perform worse economically and have significantly less access to various public goods, such as health care, public infrastructure, and education.[18]

In his book Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Colonialism, Mamdani claims the two types of rule were each sides of the same coin.[5] He explains that colonialists did not exclusively use one system of rule over another. Instead, European powers divided regions along urban-rural lines and instituted separate systems of government in each area. Mamdani refers to the formal division of rural and urban natives by colonizers as the “bifurcated state.” Urban areas were ruled directly by the colonizers under an imported system of European law, which did not recognize the validity of native institutions.[25] In contrast, rural populations were ruled indirectly by customary and traditional law and were therefore subordinate to the “civilized” urban citizenry. Rural inhabitants were viewed as “uncivilized” subjects and were deemed unfit to receive the benefits of citizenship. The rural subjects, Mamdani observed, had only a “modicum of civil rights,” and were entirely excluded from all political rights.[26]

Mamdani argues that current issues in postcolonial states are the result of colonial government partition, rather than simply poor governance as others have claimed.[27][28] Current systems — in Africa and elsewhere — are riddled with an institutional legacy that reinforces a divided society. Using the examples of South Africa and Uganda, Mamdani observed that, rather than doing away with the bifurcated model of rule, postcolonial regimes have reproduced it.[29] Although he uses only two specific examples, Mamdani maintains that these countries are simply paradigms representing the broad institutional legacy colonialism left on the world.[30] He argues that modern states have only accomplished "deracialization" and not democratization following their independence from colonial rule. Instead of pursuing efforts to link their fractured society, centralized control of the government stayed in urban areas and reform focused on “reorganizing the bifurcated power forged under colonialism.”[31] Native authorities that operated under indirect rule have not been brought into the mainstream reformation process; instead, development has been “enforced” on the rural peasantry.[29] In order to achieve autonomy, successful democratization, and good governance, states must overcome their fundamental schisms: urban versus rural, customary versus modern, and participation versus representation.[32]

4. Colonial Actions and Their Impacts

European colonizers engaged in various actions around the world that had both short term and long term consequences for the colonized. Numerous scholars have attempted to analyze and categorize colonial activities by determining if they have positive or negative outcomes. Stanley Engerman and Kenneth Sokoloff categorized activities, which were driven by regional factor endowments, by determining whether they were associated with high or low levels of economic development.[33] Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson attempted to understand what institutional changes caused previously rich countries to become poor after colonization.[34] Melissa Dell documented the persistent, damaging effects of colonial labor exploitation under the mit'a mining system in Peru; showing significant differences in height and road access between previous mit'a and non-mit'a communities.[35] Miriam Bruhn and Francisco A. Gallego employed a simple tripartite classification: good, bad, and ugly. Regardless of the system of classification, the fact remains, colonial actions produced varied outcomes which continue to be relevant.

In trying to assess the legacy of colonization, some researchers have focused on the type of political and economic institutions that existed before the arrival of Europeans. Heldring and Robinson conclude that while colonization in Africa had overall negative consequences for political and economic development in areas that had previous centralized institutions or that hosted white settlements, it possibly had a positive impact in areas that were virtually stateless, like South Sudan or Somalia.[36] In a complementary analysis, Gerner Hariri observed that areas outside Europe which had State-like institutions before 1500 tend to have less open political systems today. According to the scholar, this is due to the fact that during the colonization, European liberal institutions were not easily implemented.[37] Beyond the military and political advantages, it is possible to explain the domination of European countries over non-European areas by the fact that capitalism did not emerge as the dominant economic institution elsewhere. As Ugo Pipitone argues, prosperous economic institutions that sustain growth and innovation did not prevail in areas like China, the Arab world, or Mesoamerica because of the excessive control of these proto-States on private matters.[38]

4.1. Reorganization of Borders

Defining Borders

Throughout the era of European colonization, those in power routinely partitioned land masses and created borders that are still in place today. It has been estimated that Britain and France traced almost 40% of the entire length of today’s international boundaries.[39][40] Sometimes boundaries were naturally occurring, like rivers or mountains, but other times these borders were artificially created and agreed upon by colonial powers. The Berlin Conference of 1884 systemized European colonization in Africa and is frequently acknowledged as the genesis of the Scramble for Africa. The Conference implemented the Principle of Effective Occupation in Africa which allowed European states with even the most tenuous connection to an African region to claim dominion over its land, resources, and people. In effect, it allowed for the arbitrary construction of sovereign borders in a territory where they had never previously existed.

Jeffrey Herbst has written extensively on the impact of state organization in Africa. He notes, because the borders were artificially created, they generally do not conform to “typical demographic, ethnographic, and topographic boundaries.” Instead, they were manufactured by colonialists to advance their political goals.[41] This led to large scale issues, like the division of ethnic groups; and small scale issues, such as families’ homes being separated from their farms.[42]

William F. S. Miles of Northeastern University, argues that this perfunctory division of the entire continent created expansive ungoverned borderlands. These borderlands persist today and are havens for crimes like human trafficking and arms smuggling.[43]

Modern preservation of the colonially defined borders

Herbst notes a modern paradox regarding the colonial borders in Africa: while they are arbitrary there is a consensus among African leaders that they must be maintained. Organization of African Unity in 1963 cemented colonial boundaries permanently by proclaiming that any changes made were illegitimate.[44] This, in effect, avoided readdressing the basic injustice of colonial partition,[45] while also reducing the likelihood of inter-state warfare as territorial boundaries were considered immutable by the international community.[44]

Modern national boundaries are thus remarkably invariable, though the stability of the nation states has not followed in suit. African states are plagued by internal issues such as inability to effectively collect taxes and weak national identities. Lacking any external threats to their sovereignty, these countries have failed to consolidate power, leading to weak or failed states.[44]

Though the colonial boundaries sometimes caused internal strife and hardship, some present day leaders benefit from the desirable borders their former colonial overlords drew. For example, Nigeria's inheritance of an outlet to the sea — and the trading opportunities a port affords — gives the nation a distinct economic advantage over its neighbor, Niger.[46] Effectively, the early carving of colonial space turned naturally occurring factor endowments into state controlled assets.

4.2. Differing Colonial Investments

When European colonials entered a region, they invariably brought new resources and capital management. Different investment strategies were employed, which included focuses on health, infrastructure, or education. All colonial investments have had persistent effects on postcolonial societies, but certain types of spending have proven to be more beneficial than others. French economist Elise Huillery conducted research to determine specifically what types of public spending were associated with high levels of current development. Her findings were twofold. First, Huillery observes that the nature of colonial investments can directly influence current levels of performance. Increased spending in education lead to higher school attendance; additional doctors and medical facilities decreased preventable illnesses in children; and a colonial focus on infrastructure translated into more modernized infrastructure today. Adding to this, Huillery also learned that early colonial investments instituted a pattern of continued spending that directly influenced the quality and quantity of public goods available today.[47]

4.3. Land, Property Rights, and Labour

Land and property rights

According to Mahmood Mamdani, prior to colonization, indigenous societies did not necessarily consider land private property. Alternately, land was a communal resources that everyone could utilize. Once natives began interacting with colonial settlers, a long history of land abuse followed. Extreme examples of this include Trail of Tears, a series of forced relocations of Native Americans following the Indian Removal Act of 1830, and the apartheid system in South Africa . Australian anthropologist Patrick Wolfe points out that in these instances, natives were not only driven off land, but the land was then transferred to private ownership. He believes that the “frenzy for native land” was due to economic immigrants that belonged to the ranks of Europe’s landless.[7]

Making seemingly contradictory argument, Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson view strong property rights and ownership as an essential component of institutions that produce higher per capita income. They expand on this by saying property rights give individuals the incentive to invest, rather than stockpile, their assets. While this may appear to further encourage colonialists to exert their rights through exploitative behaviors, instead it offers protection to native populations and respects their customary ownership laws. Looking broadly at the European colonial experience, Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson explain that exploitation of natives transpired when stable property rights intentionally did not exist. These rights were never implemented in order to facilitate the predatory extraction of resources from indigenous populations. Bringing the colonial experience to the present that, they maintain that broad property rights set the stage for the effective institutions that are fundamental to strong democratic societies.[48] An example of Acemoglu, Robinson and Johnson hypothesis is in the work of La Porta, et al. In a study of the legal systems in various countries, La Porta, et al. found that in those places that were colonized by the United Kingdom and kept its common-law system, the protection of property right is stronger compared to the countries that kept the French civil law.[49]

In the case of India, Abhijit Banerjee and Lakshmi Iyer found divergent legacies of the British land tenure system in India. The areas where the property rights over the land were given to landlords registered lower productivity and agricultural investments in post-Colonial years compared to areas where land tenure was dominated by cultivators. The former areas also have lower levels of investment in health and education.[50]

Labour exploitation

Prominent Guyanese scholar and political activist Walter Rodney wrote at length about the economic exploitation of Africa by the colonial powers. In particular, he saw labourers as an especially abused group. While a capitalist system almost always employs some form of wage labour, the dynamic between labourers and colonial powers left the way open for extreme misconduct. According to Rodney, African workers were more exploited than Europeans because the colonial system produced a complete monopoly on political power and left the working class small and incapable of collective action. Combined with deep-seated racism, native workers were presented with impossible circumstances. The racism and superiority felt by the colonizers enabled them to justify the systematic underpayment of Africans even when they were working alongside European workers. Colonialists further defended their disparate incomes by claiming a higher cost of living. Rodney challenged this pretext and asserted the European quality of life and cost of living were only possible because of the exploitation of the colonies and African living standards were intentionally depressed in order to maximize revenue. In its wake, Rodney argues colonialism left Africa vastly underdeveloped and without a path forward.[51]

5. Societal Consequences of Colonialism

5.1. Ethnic Identity

The colonial changes to ethnic identity have been explored from the political, sociological, and psychological perspectives. In his book The Wretched of the Earth, Afro-Caribbean psychiatrist and revolutionary Frantz Fanon claims the colonized must “ask themselves the question constantly: ‘who am I?’"[52] Fanon uses this question to express his frustrations with fundamentally dehumanizing character of colonialism. Colonialism in all forms, was rarely an act of simple political control. Fanon argues the very act of colonial domination has the power to warp the personal and ethnic identities of natives because it operates under the assumption of perceived superiority. Natives are thus entirely divorced from their ethnic identities, which has been replaced by a desire to emulate their oppressors.[53]

Ethnic manipulation manifested itself beyond the personal and internal spheres. Scott Straus from the University of Wisconsin describes the ethnic identities that partially contributed to the Rwandan genocide. In April 1994, following the assassination of Rwanda’s President Juvénal Habyarimana, Hutus of Rwanda turned on their Tutsi neighbors and slaughtered between 500,000 and 800,000 people in just 100 days. While politically this situation was incredibly complex, the influence ethnicity had on the violence cannot be ignored. Before the German colonization of Rwanda, the identities of Hutu and Tutsi were not fixed. Germany ruled Rwanda through the Tutsi dominated monarchy and the Belgians continued this following their takeover. Belgian rule reinforced the difference between Tutsi and Hutu. Tutsis were deemed superior and were propped up as a ruling minority supported by the Belgians, while the Hutu were systematically repressed. The country’s power later dramatically shifted following the so-called Hutu Revolution, during which Rwanda gained independence from their colonizers and formed a new Hutu-dominated government. Deep-seated ethnic tensions did not leave with the Belgians. Instead, the new government reinforced the cleavage.[54]

5.2. Civil Society

Joel Migdal of the University of Washington believes weak postcolonial states have issues rooted in civil society. Rather than seeing the state as a singular dominant entity, Migdal describes “weblike societies” composed of social organizations. These organizations are a melange of ethnic, cultural, local, and familial groups and they form the basis of our society. The state is simply one actor in a much larger framework. Strong states are able to effectively navigate the intricate societal framework and exert social control over people’s behavior. Weak states, on the other hand, are lost amongst the fractionalized authority of a complex society.[55]

Migdal expands his theory of state-society relations by examining Sierra Leone. At the time of Migdal’s publication (1988), the country’s leader, President Joseph Saidu Momoh, was widely viewed as weak and ineffective. Just three years later, the country erupted into civil war, which continued for nearly 11 years. The basis for this tumultuous time, in Migdal’s estimation, was the fragmented social control implemented by British colonizers. Using the typical British system of indirect rule, colonizers empowered local chiefs to mediate British rule in the region, and in turn, the chiefs exercised social control. After achieving independence from Great Britain, the chiefs remained deeply entrenched and did not allow for the necessary consolidation of power needed to build a strong state. Migdal remarked, “Even with all the resources at their disposal, even with the ability to eliminate any single strongman, state leaders found themselves severely limited.”[56] It is necessary for the state and society to form a mutually beneficially symbiotic relationship in order for each to thrive. The peculiar nature of postcolonial politics makes this increasingly difficult.[55]

6. Ecological Impacts of Colonialism

European colonialism spread contagious diseases between Europeans and subjugated peoples.

6.1. Countering Disease

The Spain Crown organised a mission (the Balmis expedition) to transport the smallpox vaccine and establish mass vaccination programs in colonies in 1803.[57] By 1832, the federal government of the United States established a smallpox vaccination program for Native Americans.[58] Under the direction of Mountstuart Elphinstone a program was launched to increase smallpox vaccination in India.[59]

From the beginning of the 20th century onwards, the elimination or control of disease in tropical countries became a necessity for all colonial powers.[60] The sleeping sickness epidemic in Africa was arrested due to mobile teams systematically screening millions of people at risk.[61] The biggest population increases in human history occurred during the 20th century due to the decreasing mortality rate in many countries due to medical advances.[62]

6.2. Colonial Policies Contributing to Indigenous Deaths from Disease

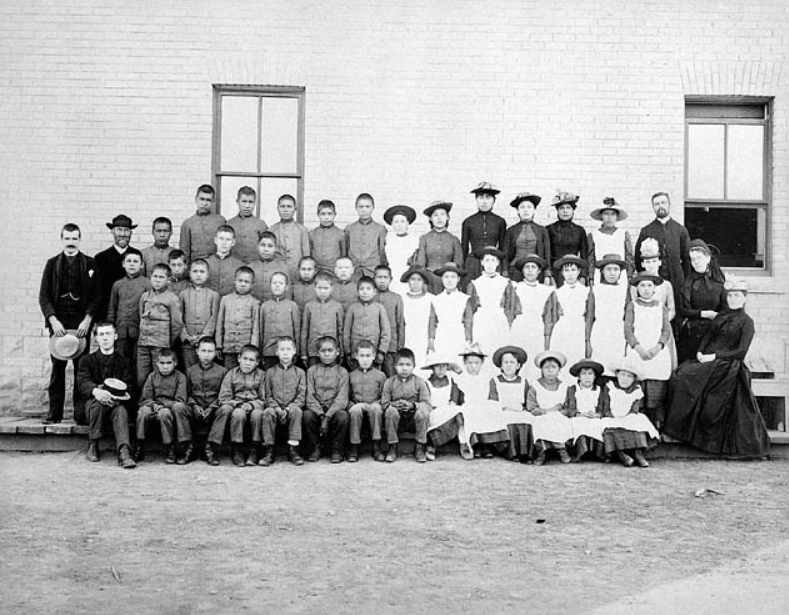

John S. Milloy published evidence indicating that colonialists had intentionally concealed information on the spread of disease in his book A National Crime: The Canadian Government and the Residential School System, 1879 to 1986 (1999). According to Milloy, the Government of Canada was aware of the origins of many diseases but maintained a secretive policy. Medical professionals had knowledge of this policy, and further, knew it was causing a higher death rate among indigenous people, yet the policy continued.[63]

Evidence suggests, government policy was not to treat natives infected with tuberculosis or smallpox, and native children infected with smallpox and tuberculosis were deliberately sent back to their homes and into native villages by residential school administrators. Within the residential schools, there was no segregation of sick students from healthy students, and students infected with deadly illnesses were frequently admitted to the schools, where infections spread among the healthy students and resulted in deaths; death rates were at least 24% and as high as 69%.[64]

Tuberculosis was the leading cause of death in Europe and North America in the 19th century, accounting for about 40% of working-class deaths in cities,[65] and by 1918 one in six deaths in France were still caused by tuberculosis. European governments, and medical professionals in Canada,[66] were well aware that tuberculosis and smallpox were highly contagious, and that deaths could be prevented by taking measures to quarantine patients and inhibit the spread of the disease. They failed to do this, however, and imposed laws that in fact ensured that these deadly diseases spread quickly among the indigenous population. Despite the high death rate among students from contagious disease, in 1920 the Canadian government made attendance at residential schools mandatory for native children, threatening non-compliant parents with fines and imprisonment. John S. Milloy argued that these policies regarding disease were not conventional genocide, but rather policies of neglect aimed at assimilating natives.[64]

Some historians, such as Roland Chrisjohn, director of Native Studies at St. Thomas University, have argued that some European colonists, having discovered that indigenous populations were not immune to certain diseases, deliberately spread diseases to gain military advantages and subjugate local peoples. In his book The Circle Game: Shadows and Substance in the Indian Residential School Experience in Canada, Chrisjohn argues that the Canadian government followed a deliberate policy amounting to genocide against native populations. British officers, including the top British commanding generals Amherst and Gage, ordered, sanctioned, paid for and conducted the use of smallpox against the Native Americans during the siege of Fort Pitt.[67] Historian David Dixon recognized, "there is no doubt that British military authorities approved of attempts to spread smallpox among the enemy."[68] Russell Thornton went further by saying, "it was deliberate British policy to infect the indians with smallpox".[69] While the exact effectiveness of the British attempts at infecting Native Americans is unknown, the outbreak of smallpox among the Indians has been documented.[70] Letters and journals from the colonial period show that British authorities discussed and agreed to the deliberate distribution of blankets infected with smallpox among Indian tribes in 1763,[71] and an incident involving William Trent and Captain Ecuyer has been regarded as one of the first instances of the use of smallpox as a biological weapon in the history of warfare.[72][73]

7. Historic Debates Surrounding Colonialism

Bartolomé de Las Casas (1484-1566) was the first Protector of the Indians appointed by the Spanish crown. During his time in the Spanish West Indies, he bore firsthand witnessed many of the atrocities committed by Spanish colonists against the natives.[74] After this experience, he reformed his view on colonialism and determined the Spanish people would suffer divine punishment if the gross mistreatment in the Indies continued. de Las Casas detailed his opinion in his book The Destruction of the Indies: A Brief Account (1552).[75]

During the sixteenth century, Spain priest and philosopher Francisco Suarez (1548-1617) expressed his objections to colonialism in his work De Bello et de Indis (On War and the Indies). In this text and others, Suarez supported natural law and conveyed his beliefs that all humans had rights to life and liberty. Along these lines, he argued for the limitation of the imperial powers of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor by underscoring the natural rights of indigenous people. Accordingly, native inhabitants of the colonial Spanish West Indies deserved independence and each island should be considered a sovereign state with all the legal powers of Spain.[76]

Prominent French Enlightenment philosopher and Encyclopédie founder Denis Diderot was openly critical of ethnocentrism and the colonisation of Tahiti. In a series of philosophical dialogues entitled Supplément au voyage de Bougainville (1772), Diderot imagines several conversations between Tahitians and Europeans. The two speakers discuss their cultural differences, which acts as a critique of European culture.[77]

8. Modern Theories of Colonialism

The effects of European colonialism have consistently drawn academic attention in the decades since decolonization. New theories continue to emerge. The field of colonial and postcolonial studies has been implemented as a major in multiple universities around the globe.[78][79][80]

8.1. Dependency Theory

The theory was introduced in the 1950s by Raul Prebisch, Director of the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America after observing that economic growth in wealthy countries did not translate into economic growth in poor countries.[81] Dependency theorists believe this is due to the import-export relationship between rich and poor countries. Walter Rodney, in his book How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, used this framework when observing the relationship between European trading companies and African peasants living in postcolonial states. Through the labour of peasants, African countries are able to gather large quantities of raw materials. Rather than being able to export these materials directly to Europe, states must work with a number of trading companies, who collaborated to keep purchase prices low. The trading companies then sold the materials to European manufactures at inflated prices. Finally the manufactured goods were returned to Africa, but with prices so high, that labourers were unable to afford them. This led to a situation where the individuals who labored extensively to gather raw materials were unable to benefit from the finished goods.[51]

8.2. Neocolonialism

Neocolonialism is the continued economic and cultural control of countries that have been decolonized. The first documented use of the term was by Former President of Ghana Kwame Nkrumah in the 1963 preamble of the Organization of African States.[82] Nkrumah expanded the concept of neocolonialism in the book Neo-Colonialism, the Last Stage of Imperialism (1965). In Nkrumah's estimation, traditional forms of colonialism have ended, but many African states are still subject to external political and economic control by Europeans.[83] Neocolonialism is related to dependency theory in that they both acknowledge the financial exploitation of poor counties by the rich,[84] but neocolonialism also includes aspects of cultural imperialism. Rejection of cultural neocolonialism formed the basis of négritude philosophy, which sought to eliminate colonial and racist attitudes by affirming the values of "the black world" and embracing "blackness.”[85][86]

8.3. Benign Colonialism

Benign colonialism is a supposed form of colonialism in which benefits outweighed risks for indigenous populations whose lands, resources, rights and freedoms were preempted by a colonising nation-state. The historical source for the concept of benign colonialism resides with John Stuart Mill who was chief examiner of the British East India Company dealing with British interests in India in the 1820s and 1830s. Mill's most well-known essays on benign colonialism are found in "Essays on some Unsettled Questions of Political Economy."[87]

Mill's view contrasted with Burkean orientalists. Mill promoted the training of a corps of bureaucrats indigenous to India who could adopt the modern liberal perspective and values of 19th century Britain.[88] Mill predicted this group's eventual governance of India would be based on British values and perspectives.

Advocates of the concept cite improved standards of health and education, employment opportunities, liberal markets, developed natural resources and introduced improved governance.[89] The first wave of benign colonialism lasted from c. 1790-1960, according to Mill. The second wave included neocolonial policies exemplified in Hong Kong, where unfettered expansion of the market created a new form of benign colonialism.[90] Political interference and military intervention in independent nation-states, such as Iraq,[88][91] is also discussed under the rubric of benign colonialism in which a foreign power preempts national governance to protect a higher concept of freedom. The term is also used in the 21st century to refer to US, French and China market activities in African countries with massive quantities of underdeveloped nonrenewable natural resources.

These views have support from some academics. Economic historian Niall Ferguson argued that empires can be a good thing provided that they are "liberal empires". He cites the British Empire as being the only example of a "liberal empire" and argues that it maintained the rule of law, benign government, free trade and, with the abolition of slavery, free labour.[92] Historian Rudolf von Albertini agrees that, on balance, colonialism can be good. He argues that colonialism was a mechanism for modernisation in the colonies and imposed a peace by putting an end to tribal warfare.[93]

Historians L.H Gann and Peter Duignan have also argued that Africa probably benefited from colonialism on balance. Although it had its faults, colonialism was probably "one of the most efficacious engines for cultural diffusion in world history".[94] These views, however, are controversial and are rejected by some who, on balance, see colonialism as bad. The economic historian David Kenneth Fieldhouse has taken a kind of middle position, arguing that the effects of colonialism were actually limited and their main weakness wasn't in deliberate underdevelopment but in what it failed to do.[95] Niall Ferguson agrees with his last point, arguing that colonialism's main weaknesses were sins of omission.[92] Marxist historian Bill Warren has argued that whilst colonialism may be bad because it relies on force, he views it as being the genesis of Third World development.[96]

References

- "Inquiring Minds: Studying Decolonization | Library of Congress Blog". 29 July 2013. http://blogs.loc.gov/loc/2013/07/inquiring-minds-studying-decolonization/. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- "The Avalon Project : THE ATLANTIC CHARTER". http://avalon.law.yale.edu/wwii/atlantic.asp.

- Hoopes, Townsend; Brinkley, Douglas (2000-01-01) (in en). FDR and the Creation of the U.N.. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300085532. https://books.google.com/books?id=OztJcfbnpDsC.

- Acemoglu, Daron; Robinson, James (December 2001). "The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation". American Economic Review 91 (5): 1369–1401. doi:10.1257/aer.91.5.1369. https://dx.doi.org/10.1257%2Faer.91.5.1369

- Mamdani, Mahmood (in English). Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism (1st ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691027937. https://www.amazon.com/Citizen-Subject-Contemporary-Colonialism-Princeton/dp/0691027935.

- Schwarz, edited by Henry; Ray, Sangeeta (2005). A companion to postcolonial studies (Reprint ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers. pp. 360–376. ISBN 0631206639.

- Wolfe, Patrick (December 2006). "Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native". Journal of Genocide Research 8 (4): 387–409. doi:10.1080/14623520601056240. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080%2F14623520601056240

- Denoon, Donald (1983). Settler capitalism : the dynamics of dependent development in the southern hemisphere. (Repr. ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0198282915.

- Morel, E. D. 1873–1924 (in English). King Leopold's rule in Africa. Nabu Press. ISBN 9781172036806. https://www.amazon.com/King-Leopolds-Africa-1873-1924-Morel/dp/1172036802.

- Morel 1923, p. 13

- Hochschild, Adam (October 6, 2005). "In the Heart of Darkness". The New York Review of Books. http://www.nybooks.com/articles/2005/10/06/in-the-heart-of-darkness/.

- Morel 1923, pp. 31–39

- Young, Crawford. The African Colonial State in Comparative Perspective. Yale University Press. p. 104. ISBN 9780300058024.

- Callaghy, Thomas M. (in English). The State-Society Struggle: Zaire in Comparative Perspective. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231057219. https://www.amazon.com/State-Society-Struggle-Zaire-Comparative-Perspective/dp/0231057210.

- Young, Crawford; Turner, Thomas Edwin (in English). The Rise and Decline of the Zairian State (1 ed.). University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299101145. https://www.amazon.com/Rise-Decline-Zairian-State/dp/0299101142.

- Doyle, Michael W. (1986). Empires (1. publ. ed.). Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. ISBN 080149334X.

- Crowder, Michael (1 July 1964). "Indirect Rule—French and British Style". Africa 34 (03): 197–205. doi:10.2307/1158021. ISSN 1750-0184. https://dx.doi.org/10.2307%2F1158021

- Iyer, Lakshmi (4 June 2010). "Direct versus Indirect Colonial Rule in India: Long-Term Consequences". Review of Economics and Statistics 92 (4): 693–713. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00023. ISSN 0034-6535. http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1162/REST_a_00023#.Vy1B-2N1odc.

- Mamdani 1996, p. 26

- Mamdani, Mahmood (1996-01-01). "Indirect Rule, Civil Society, and Ethnicity: The African Dilemma". Social Justice 23 (1/2 (63-64)): 145–150.

- Delavignette, R. (in English). Freedom and Authority in French West Africa (First U.K. Edition, First printing ed.). Oxford University Press. https://www.amazon.com/Freedom-Authority-French-West-Africa/dp/B0006D8TI6.

- Crowder, Michael. Senegal: Study in French Assimilation Policy. Institute of Race Relations/Oxford UP. https://www.amazon.com/Senegal-Study-French-Assimilation-Policy/dp/B000QXSU94.

- Betts, Raymond F. (1960-01-01) (in en). Assimilation and Association in French Colonial Theory, 1890-1914. U of Nebraska Press. p. 16. ISBN 0803262477. https://books.google.com/books?id=Qykx505NU1oC.

- Diouf, Mamadou (1998-10-01). "The French Colonial Policy of Assimilation and the Civility of the Originaires of the Four Communes (Senegal): A Nineteenth Century Globalization Project" (in en). Development and Change 29 (4): 671–696. doi:10.1111/1467-7660.00095. ISSN 1467-7660. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1467-7660.00095/abstract.

- Mamdani 1996, pp. 16-17

- Mamdani 1996, p. 17

- Bratton, Michael; van de Walle, Nicholas (in English). Democratic Experiments in Africa: Regime Transitions in Comparative Perspective. Cambridge University Press. p. 63. ISBN 9780521556125. https://www.amazon.com/Democratic-Experiments-Africa-Transitions-Comparative/dp/0521556120/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1462668627&sr=1-1&keywords=Democratic+Experiments+in+Africa%3A+Regime+Transitions+in+Comparative+Perspective.

- Chabal, Patrick; Daloz, Jean-Pascal (in English). Africa Works: Disorder as Political Instrument. Indiana University Press. pp. 37–38. ISBN 9780253212870. https://www.amazon.com/Africa-Works-Disorder-Political-Instrument/dp/0253212871.

- Mamdani 1996, pp. 287-288

- Mamdani, Mahmood (1999). "Commentary: Mahmood Mamdani response to Jean Copans' Review in Transformations 36". Transformation 39: 97–101. http://pdfproc.lib.msu.edu/?file=/DMC/African%20Journals/pdfs/transformation/tran039/tran039006.pdf.

- Mamdani 1996, p. 287

- Mamdani 1996, pp. 296-298

- Engerman, Stanley L.; Sokoloff, Kenneth L. (2002). "Factor Endowments, Inequality, and Paths of Development Among New World Economics". Economía 3 (1): 41–109.

- Acemoglu, Daron; Johnson, Simon; Robinson, James A. (2002). "Reversal of Fortune: Geography and Institutions in the Making of the Modern World Income Distribution" (in en). The Quarterly Journal of Economics 117 (4): 1231–1294. doi:10.1162/003355302320935025. ISSN 0033-5533. https://dx.doi.org/10.1162%2F003355302320935025

- Dell, Melissa (November 2010). "The Persistent Effects of Peru's Mining Mita". Econometrica 78 (6): 1863–1903. doi:10.3982/ecta8121. https://dx.doi.org/10.3982%2Fecta8121

- Heldring, Leander; Robinson, James A. (November 2012). "Colonialism and Economic Development In Africa". NBER Working Paper No. 18566. doi:10.3386/w18566. https://dx.doi.org/10.3386%2Fw18566

- Gerner Hariri, Jacob. "The Autocratic Legacy of Early Statehood". https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/11A9BAFB016B1D89F273DC523B394C7D/S0003055412000238a.pdf/autocratic_legacy_of_early_statehood.pdf.

- Pipitone, Ugo. "¿Por qué no fuera de Europa?". http://aleph.academica.mx/jspui/handle/56789/5414.

- Miles, William F. S. (2014-07-01) (in en). Scars of Partition: Postcolonial Legacies in French and British Borderlands. U of Nebraska Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780803267718. https://books.google.com/books?id=nGyTAwAAQBAJ.

- Imbert-Vier, Simon (2011-01-01) (in fr). Tracer des frontières à Djibouti: des territoires et des hommes aux XIXe et XXe siècles. KARTHALA Editions. ISBN 9782811105068. https://books.google.com/books?id=G-bZiKh9FHkC&dq=Imbert-Vier+2011&lr=&source=gbs_navlinks_s.

- "The Creation and Maintenance of National Boundaries in Africa on JSTOR".

- Miles, William F. S. (2014-01-01) (in en). Scars of Partition: Postcolonial Legacies in French and British Borderlands. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780803248328. https://books.google.com/books?id=KpUqnwEACAAJ.

- Miles 2014, p. 64

- Herbst, Jeffrey (2000-03-06) (in English). States and Power in Africa: Comparative Lessons in Authority and Control (1 ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691010281. https://www.amazon.com/States-Power-Africa-Comparative-International/dp/0691010285.

- Miles 2014, p. 296

- Miles 2014, pp. 47-102

- Huillery, Elise (1 January 2009). "History Matters: The Long-Term Impact of Colonial Public Investments in French West Africa". American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 1 (2): 176–215. doi:10.1257/app.1.2.176. https://dx.doi.org/10.1257%2Fapp.1.2.176

- Acemoglu, Daron; Johnson, Simon; Robinson, James (2005). "Institutions as a Fundamental Cause of Long-Run Growth". Handbook of Economic Growth. 1 (Part A). pp. 385–472. doi:10.1016/S1574-0684(05)01006-3. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS1574-0684%2805%2901006-3

- La Porta, Rafael; Lopez de Silanes, Florencio; Shleifer, Andrei; Vishny, Robert (1998). "Law and Finance". Journal of Political Economy 106 (6): 1113–1155. doi:10.1086/250042. https://dx.doi.org/10.1086%2F250042

- Banerjee, Abhijit; Iyer, Lakshmi (September 2005). "History, Institutions, and Economic Performance: The Legacy of Colonial Land Tenure Systems in India". American Economic Review 95 (4): 1190–1213. doi:10.1257/0002828054825574. https://dx.doi.org/10.1257%2F0002828054825574

- Rodney, Walter (2011-10-01) (in English). How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. Black Classic Press. pp. 147–203. ISBN 9781574780482. https://www.amazon.com/Europe-Underdeveloped-Africa-Walter-Rodney/dp/1574780484.

- Fanon 1961, 201

- Fanon, Frantz (in en). The Wretched of the Earth. Grove/Atlantic, Inc.. ISBN 9780802198853. https://books.google.com/books?id=-XGKFJq4eccC&source=gbs_navlinks_s.

- Straus, Scott (in en). The Order of Genocide: Race, Power, And War in Rwanda. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801444487. https://books.google.com/books?vid=9780801444487.

- "Migdal, J.S.: Strong Societies and Weak States: State-Society Relations and State Capabilities in the Third World. (Paperback)". http://press.princeton.edu/titles/4280.html.

- Migdal 1988, p. 141

- Dr. Francisco de Balmis and his Mission of Mercy, Society of Philippine Health History http://www.doh.gov.ph/sphh/balmis.htm

- Lewis Cass and the Politics of Disease: The Indian Vaccination Act of 1832 http://muse.jhu.edu/login?uri=/journals/wicazo_sa_review/v018/18.2pearson01.html

- Smallpox History - Other histories of smallpox in South Asia http://www.smallpoxhistory.ucl.ac.uk/Other%20Asia/ongoingwork.htm

- Conquest and Disease or Colonialism and Health?, Gresham College | Lectures and Events http://www.gresham.ac.uk/event.asp?PageId=45&EventId=696

- WHO Media centre (2001). Fact sheet N°259: African trypanosomiasis or sleeping sickness. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs259/en/index.html.

- The Origins of African Population Growth, by John Iliffe, The Journal of African HistoryVol. 30, No. 1 (1989), pp. 165-169 https://www.jstor.org/pss/182701

- A National Crime: the Canadian government and the residential school system, 1879-1986'. University of Manitoba Press. 1999. ISBN 978-0-88755-646-3.

- Curry, Bill and Karen Howlett (April 24, 2007). "Natives died in droves as Ottawa ignored warnings". Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/natives-died-in-droves-as-ottawa-ignored-warnings/article754798/. Retrieved February 25, 2012.

- Tuberculosis in Europe and North America, 1800–1922. The Harvard University Library, Open Collections Program: Contagion. http://ocp.hul.harvard.edu/contagion/tuberculosis.html

- Milloy, John S. (1999). A National Crime: the Canadian government and the residential school system, 1879-1986. University of Manitoba Press. ISBN 978-0-88755-646-3.

- Chrisjohn, Roland; Young, Sherri; Maraun, Michael (2006-01-17) (in English). The Circle Game: Shadows and Substance in the Indian Residential School Experience in Canada Revised Edition (Revised ed.). Penticton, BC: Theytus Books. ISBN 9781894778053. https://www.amazon.com/Circle-Game-Substance-Residential-Experience/dp/1894778057.

- Dixon, David; Never Come to Peace Again: Pontiac's Uprising and the Fate of the British Empire in North America; (pg. 152-155); University of Oklahoma Press; 2005; ISBN:0-8061-3656-1 https://books.google.com/books?id=UeaN0-Ra64oC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Thornton, Russel (1987). American Indian Holocaust and Survival: A Population History : Since 1492. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-0-8061-2220-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=9iQYSQ9y60MC&pg=PA79.

- Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 152–55; McConnell, A Country Between, 195–96; Dowd, War under Heaven, 190. For historians who believe the attempt at infection was successful, see Nester, Haughty Conquerors", 112; Jennings, Empire of Fortune, 447–48.

- White, Matthew (2012). The Great Big Book of Horrible Things: The Definitive Chronicle of History's 100 Worst Atrocities. London: W.W. Norton and Co.. pp. 185–6. ISBN 978-0-393-08192-3.

- Ann F. Ramenofsky, Vectors of Death: The Archaeology of European Contact (Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1987):

- Robert L. O'Connell, Of Arms and Men: A History of War, Weapons, and Aggression (NY and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989); Pg. 171

- Zinn, Howard (2011-01-04) (in en). The Zinn Reader: Writings on Disobedience and Democracy. Seven Stories Press. ISBN 9781583229460. https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Zinn_Reader.html?id=VotAP9b-KjkC.

- Casas, Bartolomé de Las (1974-01-01) (in en). The Devastation of the Indies: A Brief Account. JHU Press. ISBN 9780801844300. https://books.google.com/books?id=krP0qAvXK4QC.

- Hill, Benjamin, ed (2012-03-24) (in English). The Philosophy of Francisco Suarez (1 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199583645. https://www.amazon.com/Philosophy-Francisco-Suarez-Benjamin-Hill/dp/0199583641.

- Bougainville, Louis Antoine de; Sir, Banks, Joseph (1772-01-01). Supplément au voyage de M. de Bougainville ou Journal d'un voyage autour du monde, fait par MM. Banks & Solander, Anglois, en 1768, 1769, 1770, 1771. A Paris: Chez Saillant & Nyon, Libraires .... ISBN 0665323697. https://openlibrary.org/books/OL24280417M/Suppl%C3%A9ment_au_voyage_de_M._de_Bougainville_ou_Journal_d'un_voyage_autour_du_monde_fait_par_MM._Banks.

- "Institute for Colonial and Postcolonial Studies - Faculty of Arts - University of Leeds". http://www.leeds.ac.uk/arts/info/20044/institute_for_colonial_and_postcolonial_studies.

- University, La Trobe. "Colonial and Post Colonial Studies". http://www.latrobe.edu.au/humanities/research/specialisations/post-colonial.

- "Tufts University: Colonialism Studies: Home". http://as.tufts.edu/ColonialismStudies/.

- CEPAL. "Textos Esenciales | Raúl Prebisch y los desafíos del Siglo XXI". http://prebisch.cepal.org/en/works/economic-development-latin-america-and-its-principal-problems.

- Tondini, Matteo (2010-02-25) (in en). Statebuilding and Justice Reform: Post-Conflict Reconstruction in Afghanistan. Routledge. ISBN 9781135233181. https://books.google.com/books?id=T0COAgAAQBAJ.

- Nkrumah, Kwame (1974-01-01) (in en). Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism. Panaf. ISBN 9780901787231. https://books.google.com/books?id=53xumwEACAAJ.

- Nkrumah 1965, pp. ix-xx

- Diagne, Souleymane Bachir (2016-01-01). Zalta, Edward N.. ed. Négritude (Spring 2016 ed.). http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2016/entries/negritude/.

- Césaire, Aimé (2001-01-01) (in en). Discourse on Colonialism. NYU Press. ISBN 9781583674109. https://books.google.com/books?id=yaDLD4O5MdIC.

- Mill, John Stuart. 1844. "Essays on some Unsettled Questions of Political Economy." http://www.gutenberg.org/files/12004/12004-8.txt

- Doyle, Michael W. 2006. "Sovereignty and Humanitarian Military Intervention." Columbia University. http://www.princeton.edu/~pcglobal/conferences/normative/papers/Session5_Doyle.pdf

- Robert Woodberry- The Social Impact of Missionary Higher Education http://www.prc.utexas.edu/prec/en/publications/articles/SocialImpact_2007.pdf

- Liu, Henry C. K. 2003. "China: a Case of Self-Delusion: Part 1: From colonialism to confusion." Asia Times. May 14. http://www.atimes.com/atimes/China/EE14Ad01.html

- Campo, Juan E. 2004. "Benign Colonialism? The Iraq War: Hidden Agendas and Babylonian Intrigue." Interventionism. 26:1. Spring. http://hir.harvard.edu/articles/?id=1223

- Niall Ferguson, Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World and Colossus: The Rise and Fall of the American Empire

- Albertini, Rudolph von, and Wirz, Albert. European Colonial Rule, 1880-1914: The Impact of the West on India, South East Asia and Africa

- Lewis H. Gann and Peter Duignan, The Burden of Empire: A Reappraisal of Western Colonialism South of the Sahara

- D. K. Fieldhouse, The West and the Third World

- Warren, Bill (1980). Imperialism: Pioneer of Capitalism. Verso. p. 113.