| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jósé Manuel Guillamón | -- | 2502 | 2022-10-11 14:26:21 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | + 3 word(s) | 2505 | 2022-10-12 03:15:43 | | |

Video Upload Options

Under detrimental conditions such as those found during wine fermentation, yeast populations need to promote adaptive responses in order to survive in this harsh environment. Wine yeast has developed a plethora of genetic mechanisms to adapt to the wine niche, including variation of the copy number of certain genes, structural rearrangements, horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or interspecific hybridization. From this set of genomic adaptations, structural variations leading to duplications of genes, chromosomic segments, full chromosomes or even the complete genome are the major cause of adaptation. Besides its great impact by changing dosage, this structural variation can be the substrate for evolution and even the generation of new genes.

1. Introduction

2. Sugar Transporters (HXT3 and FSY1)

The ability to consume fructose in wine yeast is crucial at the end of fermentation in order to maintain good fermentation rates and therefore to reach dryness. The transport of hexoses in S. cerevisiae occurs by facilitated diffusion carriers encoded by different genes, some of them belonging to HXT family [38]. In S. cerevisiae, from the 17 HXT genes, only seven of them (HXT1–HXT7) are needed to grow on glucose or fructose [39].

3. Cysteine-S-β-lyase IRC7

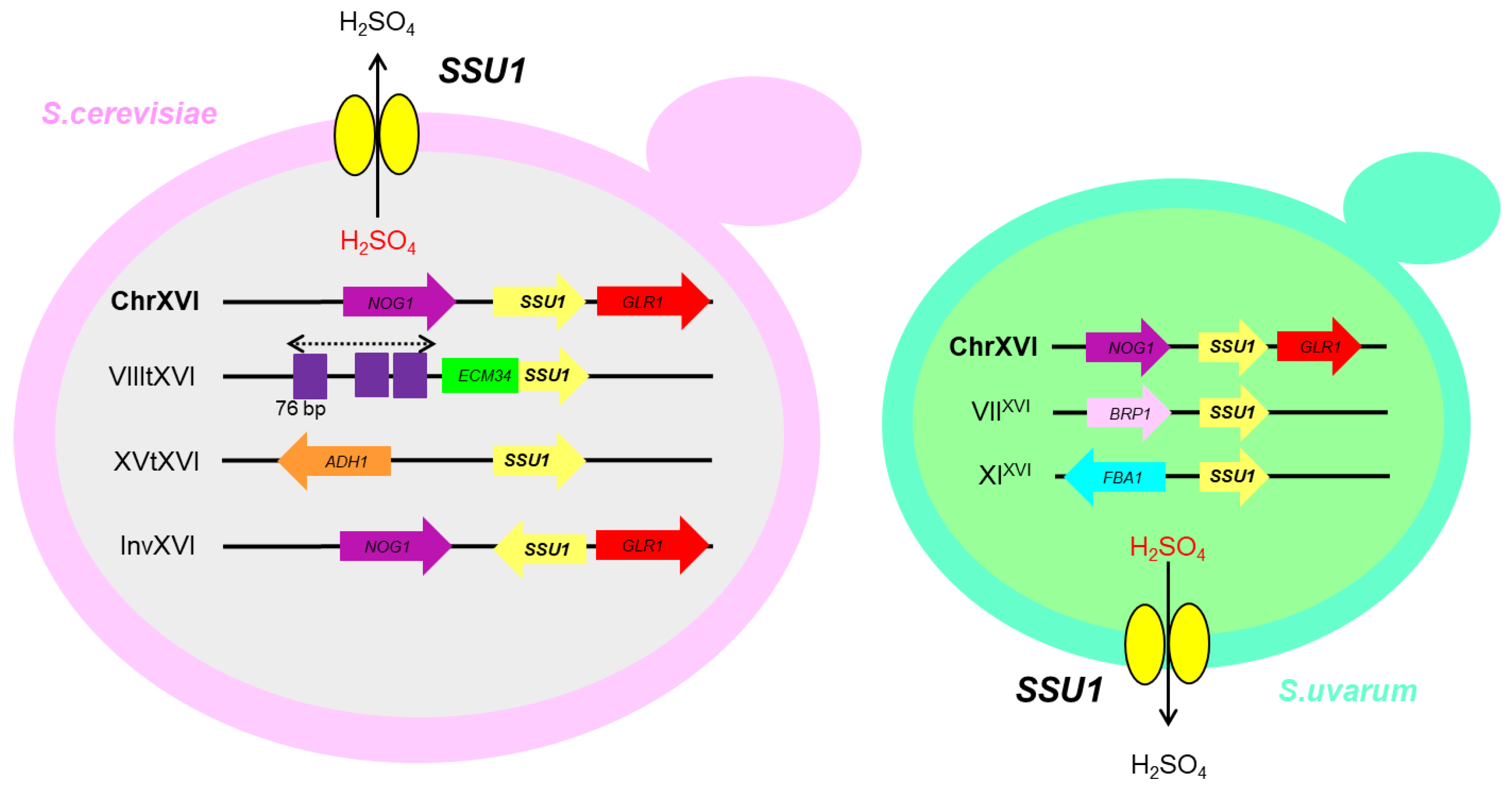

4. Sulphite Resistance

5. Copper Tolerance

6. Oligopeptide Uptake: FOT Genes

7. Biofilm Formation: FLO Genes

Flor strains, which are involved in sherry wine production, are able to form a biofilm on the wine surface when fermentation is finished and change their metabolism from fermentative to oxidative in the presence of ethanol and low amounts of fermentable sugar [24][73][74]. Although flor yeasts are closely related to the wine strains [75], their unique life style have rendered their genetic structure more complex. Recently, genomic analysis stated that flor yeasts are an independent clade that emerged from the wine group through a relatively recent bottleneck event [76].

The ability to form a biofilm is largely dependent on the acquisition of two changes in the FLO11 gene [77], which encodes for hydrophobic cell wall glycoprotein that regulates cell adhesion, pseudohyphae, chronological aging and biofilm formation [78][79][80]. The first change was a 111-nt deletion within the promoter region of FLO11, which led to an increased expression [77][81]. This deletion is characteristic of Spanish, French, Italian, and Hungarian sherry strains [75].

Furthermore, FLO11, like the majority of the genes encoding cell wall proteins, contain intragenic tandem repeats [82]. In this regard, rearrangement in the central tandem repeat section of the ORF was responsible for producing a more hydrophobic FLO11, increasing the capacity of the yeast cells to adhere to each other [77][83]. However, the expanded FLO11 allele present in wild flor yeasts is highly unstable under non-selective conditions [83].

8. Inactivation of Aquaporin Genes

9. Interspecific Hybridization

References

- Steensels, J.L.; Meersman, E.; Snoek, T.; Saels, V.; Verstrepen, K.J. Large-scale selection and breeding to generate industrial yeasts with superior aroma production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 6965–6975.

- Parapouli, M.; Vasileiadis, A.; Afendra, A.S.; Hatziloukas, E. Saccharomyces cerevisiae and its industrial applications. AIMS Microbiol. 2020, 6, 1–31.

- Legras, J.; Galeote, V.; Bigey, F.; Camarasa, C.; Marsit, S.; Nidelet, T.; Sanchez, I.; Couloux, A.; Guy, J.; Franco-duarte, R.; et al. Adaptation of S. cerevisiae to fermented food environments reveals remarkable genome plasticity and the footprints of domestication. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1712–1727.

- Alsammar, H.; Delneri, D. An update on the diversity, ecology and biogeography of the Saccharomyces genus. FEMS Yeast Res. 2020, 20, foaa013.

- Molinet, J.; Cubillos, F.A. Wild yeast for the future: Exploring the use of wild strains for wine and beer fermentation. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 589350.

- García-Ríos, E.; López-Malo, M.; Guillamón, J.M. Global phenotypic and genomic comparison of two Saccharomyces cerevisiae wine strains reveals a novel role of the sulfur assimilation pathway in adaptation at low temperature fermentations. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 1059.

- García-Ríos, E.; Ramos-Alonso, L.; Guillamón, J.M. Correlation between low temperature adaptation and oxidative stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1199.

- García-Ríos, E.; Guillamón, J.M. Mechanisms of yeast adaptation to wine fermentations. Prog. Mol. Subcell. Biol. 2019, 58, 37–59.

- Brice, C.; Sanchez, I.; Bigey, F.; Legras, J.-L.; Blondin, B. A genetic approach of wine yeast fermentation capacity in nitrogen-starvation reveals the key role of nitrogen signaling. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 495.

- Warringer, J.; Zörgö, E.; Cubillos, F.A.; Zia, A.; Gjuvsland, A.; Simpson, J.T.; Forsmark, A.; Durbin, R.; Omholt, S.W.; Louis, E.J.; et al. Trait variation in yeast is defined by population history. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002111.

- Taymaz-Nikerel, H.; Cankorur-Cetinkaya, A.; Kirdar, B. Genome-wide transcriptional response of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to stress-induced perturbations. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2016, 4, 17.

- Steensels, J.; Gallone, B.; Voordeckers, K.; Verstrepen, K.J. Domestication of Industrial Microbes. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, R381–R393.

- Pronk, J.T.; Steensma, H.Y.; Van Dijken, J.P. Pyruvate metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 1996, 12, 1607–1633.

- Belda, I.; Ruiz, J.; Santos, A.; Van Wyk, N.; Pretorius, I.S. Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Trends Genet. 2019, 35, 956–957.

- Piskur, J.; Rozpedowska, E.; Polakova, S.; Merico, A.; Compagno, C. How did Saccharomyces evolve to become a good brewer? Trends Genet. 2006, 22, 183–186.

- Hagman, A.; Säll, T.; Compagno, C.; Piskur, J. Yeast “Make-Accumulate-Consume” life strategy evolved as a multi-step process that predates the whole genome duplication. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68734.

- Pfeiffer, T.; Schuster, S.; Bonhoeffer, S. Cooperation and competition in the evolution of ATP-producing pathways. Science 2001, 292, 504–507.

- Albergaria, H.; Arneborg, N. Dominance of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in alcoholic fermentation processes: Role of physiological fitness and microbial interactions. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 2035–2046.

- Yue, J.-X.; Li, J.; Aigrain, L.; Hallin, J.; Persson, K.; Oliver, K.; Bergström, A.; Coupland, P.; Warringer, J.; Cosentino Lagomarsino, M.; et al. Contrasting genome dynamics between domesticated and wild yeasts. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 913–924.

- Gallone, B.; Steensels, J.; Prahl, T.; Soriaga, L.; Saels, V.; Herrera-Malaver, B.; Merlevede, A.; Roncoroni, M.; Voordeckers, K.; Miraglia, L.; et al. Domestication and divergence of Saccharomyces cerevisiae beer yeasts. Cell 2016, 166, 1397–1410.e16.

- Liti, G.; Carter, D.M.; Moses, A.M.; Warringer, J.; Parts, L.; James, S.A.; Davey, R.P.; Roberts, I.N.; Burt, A.; Koufopanou, V.; et al. Population genomics of domestic and wild yeasts. Nature 2009, 458, 337–341.

- Strope, P.K.; Skelly, D.A.; Kozmin, S.G.; Mahadevan, G.; Stone, E.A.; Magwene, P.M.; Dietrich, F.S.; McCusker, J.H. The 100-genomes strains, an S. cerevisiae resource that illuminates its natural phenotypic and genotypic variation and emergence as an opportunistic pathogen. Genome Res. 2015, 125, 762–774.

- Fay, J.C.; Benavides, J.A. Evidence for domesticated and wild populations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS Genet. 2005, 1, e5.

- Legras, J.L.; Merdinoglu, D.; Cornuet, J.M.; Karst, F. Bread, beer and wine: Saccharomyces cerevisiae diversity reflects human history. Mol. Ecol. 2007, 16, 2091–2102.

- Barbosa, R.; Pontes, A.; Santos, R.O.; Montandon, G.G.; De Ponzzes-Gomes, C.M.; Morais, P.B.; Gonçalves, P.; Rosa, C.A.; Sampaio, J.D.S.P. Multiple rounds of artificial selection promote microbe secondary domestication- the case of cachaça yeasts. Genome Biol. Evol. 2018, 10, 1939–1955.

- Pontes, A.; Hutzler, M.; Brito, P.H.; Sampaio, J.P. Revisiting the taxonomic synonyms and populations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae—phylogeny, phenotypes, ecology and domestication. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 903.

- Peter, J.; De Chiara, M.; Friedrich, A.; Yue, J.-X.; Pflieger, D.; Bergstrom, A.; Sigwalt, A.; Barré, B.; Freel, K.; Llored, A.; et al. Genome evolution across 1,011 Saccharomyces cerevisiae isolates. Nature 2018, 556, 339–344.

- Schacherer, J.; Shapiro, J.A.; Ruderfer, D.M.; Kruglyak, L. Comprehensive polymorphism survey elucidates population structure of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 2009, 458, 342–345.

- Giannakou, K.; Cotterrell, M.; Delneri, D. Genomic adaptation of Saccharomyces species to industrial environments. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 916.

- Guillamón, J.M.; Barrio, E. Genetic polymorphism in wine yeasts: Mechanisms and methods for its detection. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 806.

- Gonçalves, M.; Pontes, A.; Almeida, P.; Barbosa, R.; Serra, M.; Libkind, D.; Hutzler, M.; Gonçalves, P.; Sampaio, J.P. Distinct domestication trajectories in top-fermenting beer yeasts and wine yeasts. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, 2750–2761.

- Marsit, S.; Dequin, S. Diversity and adaptive evolution of Saccharomyces wine yeast: A review. FEMS Yeast Res. 2015, 15, fov067.

- Mendes, I.; Sanchez, I.; Franco-duarte, R.; Camarasa, C.; Schuller, D.; Dequin, S.; Sousa, M.J. Integrating transcriptomics and metabolomics for the analysis of the aroma profiles of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains from diverse origins. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 455.

- Franco-Duarte, R.; Mendes, I.; Umek, L.; Drumonde-Neves, J.; Zupan, B.; Schuller, D. Computational models reveal genotype-phenotype associations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 2014, 31, 265–277.

- Franco-Duarte, R.; Bigey, F.; Carreto, L.; Mendes, I.; Dequin, S.; Santos, M.A.S.; Pais, C.; Schuller, D. Intrastrain genomic and phenotypic variability of the commercial Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain Zymaflore VL1 reveals microevolutionary adaptation to vineyard environments. FEMS Yeast Res. 2015, 15, fov063.

- Liti, G.; Louis, E.J. Yeast Evolution and Comparative Genomics. Annu. Rev. Microbiol 2005, 59, 135–153.

- Bergström, A.; Simpson, J.T.; Salinas, F.; Barré, B.; Parts, L.; Zia, A.; Nguyen Ba, A.N.; Moses, A.M.; Louis, E.J.; Mustonen, V.; et al. A high-definition view of functional genetic variation from natural yeast genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2014, 31, 872–888.

- Kruckeberg, A.L. The hexose transporter family of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Arch. Microbiol. 1996, 166, 283–292.

- Luyten, K.; Riou, C.; Blondin, B. The hexose transporters of Saccharomyces cerevisiae play different roles during enological fermentation. Yeast 2002, 19, 713–726.

- Novo, M.; Dé, F.; Bigey, R.; Beyne, E.; Galeote, V.; Gavory, R.; Mallet, S.; Cambon, B.; Legras, J.-L.J.-L.; Wincker, P.; et al. Eukaryote-to-eukaryote gene transfer events revealed by the genome sequence of the wine yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae EC1118. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 16333–16338.

- Marsit, S.; Mena, A.; Bigey, F.; Sauvage, F.X.; Couloux, A.; Guy, J.; Legras, J.L.; Barrio, E.; Dequin, S.; Galeote, V. Evolutionary advantage conferred by an eukaryote-to-eukaryote gene transfer event in wine yeasts. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 1695–1707.

- Galeote, V.; Novo, M.; Salema-Oom, M.; Brion, C.; Valério, E.; Gonçalves, P.; Dequin, S. FSY1, a horizontally transferred gene in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae EC1118 wine yeast strain, encodes a high-affinity fructose/H+ symporter. Microbiology 2010, 156, 3754–3761.

- Guillaume, C.; Delobel, P.; Sablayrolles, J.M.; Blondin, B. Molecular basis of fructose utilization by the wine yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: A mutated HXT3 allele enhances fructose fermentation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 2432–2439.

- Charpentier, C.; Colin, A.; Alais, A.; Legras, J.L. French Jura flor yeasts: Genotype and technological diversity. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2009, 95, 263–273.

- Roncoroni, M.; Santiago, M.; Hooks, D.O.; Moroney, S.; Harsch, M.J.; Lee, S.A.; Richards, K.D.; Nicolau, L.; Gardner, R.C. The yeast IRC7 gene encodes a β-lyase responsible for production of the varietal thiol 4-mercapto-4-methylpentan-2-one in wine. Food Microbiol. 2011, 28, 926–935.

- Santiago, M.; Gardner, R.C. Yeast genes required for conversion of grape precursors to varietal thiols in wine. FEMS Yeast Res. 2015, 15, fov034.

- Belda, I.; Ruiz, J.; Navascués, E.; Marquina, D.; Santos, A. Improvement of aromatic thiol release through the selection of yeasts with increased β-lyase activity. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 225, 1–8.

- Ruiz, J.; de Celis, M.; Martín-Santamaría, M.; Benito-Vázquez, I.; Pontes, A.; Lanza, V.F.; Sampaio, J.P.; Santos, A.; Belda, I. Global distribution of IRC7 alleles in Saccharomyces cerevisiae populations: A genomic and phenotypic survey within the wine clade. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 23, 3182–3195.

- Cordente, A.G.; Borneman, A.R.; Bartel, C.; Capone, D.; Solomon, M.; Roach, M.; Curtin, C.D. Inactivating mutations in Irc7p are common in wine yeasts, attenuating carbon-sulfur beta-lyase activity and volatile sulfur compound production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85, e02684-18.

- Santiago, M.; Gardner, R.C. The IRC7 gene encodes cysteine desulphydrase activity and confers on yeast the ability to grow on cysteine as a nitrogen source. Yeast 2015, 32, 519–532.

- Zara, G.; Nardi, T. Yeast metabolism and its exploitation in emerging winemaking trends: From sulfite tolerance to sulfite reduction. Fermentation 2021, 7, 57.

- Pérez-Ortín, J.E.; Querol, A.; Puig, S.; Barrio, E. Molecular characterization of a chromosomal rearrangement involved in the adaptive evolution of yeast strains. Genome Res. 2002, 12, 1533–1539.

- Zimmer, A.; Durand, C.; Loira, N.; Durrens, P.; Sherman, D.J.; Marullo, P. QTL dissection of lag phase in wine fermentation reveals a new translocation responsible for Saccharomyces cerevisiae adaptation to sulfite. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86298.

- García-Ríos, E.; Nuévalos, M.; Barrio, E.; Puig, S.; Guillamón, J.M. A new chromosomal rearrangement improves the adaptation of wine yeasts to sulfite. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 21, 1771–1781.

- Martins, V.; Teixeira, A.; Bassil, E.; Hanana, M.; Blumwald, E.; Gerós, H. Copper-based fungicide Bordeaux mixture regulates the expression of Vitis vinifera copper transporters. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2014, 20, 451–458.

- Carpenè, E.; Andreani, G.; Isani, G. Metallothionein functions and structural characteristics. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2007, 21, 35–39.

- Fogel, S.; Welch, J.W. Tandem gene amplification mediates copper resistance in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1982, 79, 5342–5346.

- Adamo, G.M.; Brocca, S.; Passolungui, S.; Salvato, B.; Lotti, M. Laboratory evolution of copper tolerant yeast strains. Microb. Cell Fact. 2012, 11, 1.

- Crosato, G.; Nadai, C.; Carlot, M.; Garavaglia, J.; Ziegler, D.R.; Rossi, R.C.; De Castilhos, J.; Campanaro, S.; Treu, L.; Giacomini, A.; et al. The impact of CUP1 gene copy-number and XVI-VIII/XV-XVI translocations on copper and sulfite tolerance in vineyard Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain populations. FEMS Yeast Res. 2020, 20, foaa028.

- Liu, J.; Martin-Yken, H.; Bigey, F.; Dequin, S.; François, J.M.; Capp, J.P. Natural yeast promoter variants reveal epistasis in the generation of transcriptional-mediated noise and its potential benefit in stressful conditions. Genome Biol. Evol. 2015, 7, 969–984.

- Gerstein, A.C.; Ono, J.; Lo, D.S.; Campbell, M.L.; Kuzmin, A.; Otto, S.P. Too much of a good thing: The unique and repeated paths toward copper adaptation. Genetics 2014, 199, 555–571.

- Henschke, P.A.; Jiranek, V. Yeast: Metabolism of nitrogen compounds. In Wine Microbiology and Biotechnology; Fleet, G.H., Ed.; Harwood Academic Publishers: Cambridge, UK, 1993; pp. 77–164. ISBN 0-415-27850-3.

- Perry, J.R.; Basrai, M.A.; Steiner, H.Y.; Naider, F.; Becker, J.M. Isolation and characterization of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae peptide transport gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994, 14, 104–115.

- Nelissen, B.; De Wachter, R.; Goffeau, A. Classification of all putative permeases and other membrane plurispanners of the major facilitator superfamily encoded by the complete genome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1997, 21, 113–134.

- Hauser, M.; Donhardt, A.M.; Barnes, D.; Naider, F.; Becker, J.M. Enkephalins are transported by a novel eukaryotic peptide uptake system. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 3037–3041.

- Wiles, A.M.; Cai, H.; Naider, F.; Becker, J.M. Nutrient regulation of oligopeptide transport in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiology 2006, 152, 3133–3145.

- Damon, C.; Vallon, L.; Zimmermann, S.; Haider, M.Z.; Galeote, V.; Dequin, S.; Luis, P.; Fraissinet-Tachet, L.; Marmeisse, R. A novel fungal family of oligopeptide transporters identified by functional metatranscriptomics of soil eukaryotes. ISME J. 2011, 5, 1871–1880.

- Becerra-Rodríguez, C.; Marsit, S.; Galeote, V. Diversity of oligopeptide transport in yeast and its impact on adaptation to winemaking conditions. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 602.

- Almeida, P.; Gonçalves, C.; Teixeira, S.; Libkind, D.; Bontrager, M.; Masneuf-Pomarède, I.; Albertin, W.; Durrens, P.; Sherman, D.J.; Marullo, P.; et al. A Gondwanan imprint on global diversity and domestication of wine and cider yeast Saccharomyces uvarum. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4044.

- Marullo, P.; Aigle, M.; Bely, M.; Masneuf-Pomarède, I.; Durrens, P.; Dubourdieu, D.; Yvert, G. Single QTL mapping and nucleotide-level resolution of a physiologic trait in wine Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains. FEMS Yeast Res. 2007, 7, 941–952.

- Ibstedt, S.; Stenberg, S.; Bages, S.; Gjuvsland, A.B.; Salinas, F.; Kourtchenko, O.; Samy, J.K.A.; Blomberg, A.; Omholt, S.W.; Liti, G.; et al. Concerted evolution of life stage performances signals recent selection on yeast nitrogen use. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 153–161.

- MacLean, R.C. The tragedy of the commons in microbial populations: Insights from theoretical, comparative and experimental studies. Heredity 2008, 100, 233–239.

- Alexandre, H. Flor yeasts of Saccharomyces cerevisiae-Their ecology, genetics and metabolism. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 167, 269–275.

- Avdanina, D.; Zghun, A. Sherry wines: Worldwide production, chemical composition and screening conception for flor yeasts. Fermentation 2022, 8, 381.

- Legras, J.-L.; Erny, C.; Charpentier, C. Population structure and comparative genome hybridization of European flor yeast reveal a unique group of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains with few gene duplications in their genome. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e108089.

- Coi, A.L.; Bigey, F.; Mallet, S.; Marsit, S.; Zara, G.; Gladieux, P.; Galeote, V.; Budroni, M.; Dequin, S.; Legras, J.L. Genomic signatures of adaptation to wine biological ageing conditions in biofilm-forming flor yeasts. Mol. Ecol. 2017, 26, 2150–2166.

- Fidalgo, M.; Barrales, R.R.; Ibeas, J.I.; Jimenez, J. Adaptive evolution by mutations in the FLO11 gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 11228–11233.

- Barré, B.P.; Hallin, J.; Yue, J.X.; Persson, K.; Mikhalev, E.; Irizar, A.; Holt, S.; Thompson, D.; Molin, M.; Warringer, J.; et al. Intragenic repeat expansion in the cell wall protein gene HPF1 controls yeast chronological aging. Genome Res. 2020, 30, 697–710.

- Váchová, L.; Štoví, V.; Hlaváček, O.; Chernyavskiy, O.; Štěpánek, L.; Kubínová, L.; Palková, Z. Flo11p, drug efflux pumps, and the extracellular matrix cooperate to form biofilm yeast colonies. J. Cell Biol. 2011, 194, 679–687.

- Douglas, L.M.; Li, L.; Yang, Y.; Dranginis, A.M. Expression and characterization of the flocculin Flo11/Muc1, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae mannoprotein with homotypic properties of adhesion. Eukaryot. Cell 2007, 6, 2214–2221.

- Bumgarner, S.L.; Dowell, R.D.; Grisafi, P.; Gifford, D.K.; Fink, G.R. Toggle involving cis-interfering noncoding RNAs controls variegated gene expression in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 18321–18326.

- Verstrepen, K.J.; Jansen, A.; Lewitter, F.; Fink, G.R. Intragenic tandem repeats generate functional variability. Nat. Genet. 2005, 37, 986–990.

- Fidalgo, M.; Barrales, R.R.; Jimenez, J. Coding repeat instability in the FLO11 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 2008, 25, 879–889.

- Sabir, F.; Loureiro-Dias, M.C.; Prista, C. Comparative analysis of sequences, polymorphisms and topology of yeasts aquaporins and aquaglyceroporins. FEMS Yeast Res. 2016, 16, fow025.

- Will, J.L.; Kim, H.S.; Clarke, J.; Painter, J.C.; Fay, J.C.; Gasch, A.P. Incipient balancing selection through adaptive loss of aquaporins in natural Saccharomyces cerevisiae populations. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6, e1000893.

- Pettersson, N.; Filipsson, C.; Becit, E.; Brive, L.; Hohmann, S. Aquaporins in yeasts and filamentous fungi. Biol. Cell 2005, 97, 487–500.

- Schluter, D. Evidence for ecological speciation and its alternative. Science 2009, 323, 737–741.

- Morales, L.; Dujon, B. Evolutionary role of interspecies hybridization and genetic exchanges in yeasts. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2012, 76, 721–739.

- Stelkens, R.; Bendixsen, D.P. The evolutionary and ecological potential of yeast hybrids. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2022, 76, 101958.

- Bendixsen, D.P.; Frazão, J.G.; Stelkens, R. Saccharomyces yeast hybrids on the rise. Yeast 2022, 39, 40–54.

- Langdon, Q.K.; Peris, D.; Baker, E.P.C.P.; Opulente, D.A.; Bond, U.; Gonçalves, P.; Sampaio, J.P.; Libkind, D.; Nguyen, H.V.; Bond, U.; et al. Fermentation innovation through complex hybridization of wild and domesticated yeasts. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 3, 1576–1586.

- González, S.S.; Gallo, L.; Climent, D.; Barrio, E.; Querol, A.; Climent, M.A.D.; Barrio, E.; Querol, A. Enological characterization of natural hybrids from Saccharomyces cerevisiae and S. kudriavzevii. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007, 116, 11–18.

- Tronchoni, J.; Gamero, A.; Arroyo-López, F.N.; Barrio, E.; Querol, A. Differences in the glucose and fructose consumption profiles in diverse Saccharomyces wine species and their hybrids during grape juice fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2009, 134, 237–243.

- Arroyo-López, F.N.; Orlic, S.; Querol, A.; Barrio, E. Effects of temperature, pH and sugar concentration on the growth parameters of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, S. kudriavzevii and their interspecific hybrid. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2009, 131, 120–127.

- Belloch, C.; Orlic, S.; Barrio, E.; Querol, A. Fermentative stress adaptation of hybrids within the Saccharomyces sensu stricto complex. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 122, 188–195.

- Peris, D.; Pérez-Torrado, R.; Hittinger, C.T.; Barrio, E.; Querol, A. On the origins and industrial applications of Saccharomyces cerevisiae × Saccharomyces kudriavzevii hybrids. Yeast 2009, 26, 545–551.

- Origone, A.C.; del Mónaco, S.M.; Ávila, J.R.; González Flores, M.; Rodríguez, M.E.; Lopes, C.A. Tolerance to winemaking stress conditions of Patagonian strains of Saccharomyces eubayanus and Saccharomyces uvarum. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 123, 450–463.

- Querol, A.; Pérez-Torrado, R.; Alonso-del-Real, J.; Minebois, R.; Stribny, J.; Oliveira, B.M.; Barrio, E. New Trends in the Uses of Yeasts in Oenology, 1st ed.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 85, ISBN 1043-4526.

- García-Ríos, E.; Querol, A.; Guillamón, J.M. iTRAQ-based proteome profiling of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and cryotolerant species S. uvarum and S. kudriavzevii during low-temperature wine fermentation. J. Proteom. 2016, 146, 70–79.

- Alonso-del-Real, J.; Pérez-Torrado, R.; Querol, A.; Barrio, E. Dominance of wine Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains over S. kudriavzevii in industrial fermentation competitions is related to an acceleration of nutrient uptake and utilization. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 21, 1627–1644.

- Minebois, R.; Pérez-Torrado, R.; Querol, A. Metabolome segregation of four strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Saccharomyces uvarum and Saccharomyces kudriavzevii conducted under low temperature oenological conditions. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 22, 3700–3721.

- Navarro, D.P. Genome characterization of natural Saccharomyces hybrids of biotechnological interest. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat de València, València, Spain, 2012.

- Gamero, A.; Tronchoni, J.; Querol, A.; Belloch, C. Production of aroma compounds by cryotolerant Saccharomyces species and hybrids at low and moderate fermentation temperatures. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 114, 1405–1414.

- Stribny, J.; Gamero, A.; Pérez-Torrado, R.; Querol, A. Saccharomyces kudriavzevii and Saccharomyces uvarum differ from Saccharomyces cerevisiae during the production of aroma-active higher alcohols and acetate esters using their amino acidic precursors. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 205, 41–46.

- Replansky, T.; Koufopanou, V.; Greig, D.; Bell, G. Saccharomyces sensu stricto as a model system for evolution and ecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2008, 23, 494–501.

- Erny, C.; Raoult, P.; Alais, A.; Butterlin, G.; Delobel, P.; Matei-Radoi, F.; Casaregola, S.; Legras, J.L. Ecological success of a group of Saccharomyces cerevisiae/Saccharomyces kudriavzevii hybrids in the northern European wine-making environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 3256–3265.

- Lopandic, K.; Gangl, H.; Wallner, E.; Tscheik, G.; Leitner, G.; Querol, A.; Borth, N.; Breitenbach, M.; Prillinger, H.; Tiefenbrunner, W. Genetically different wine yeasts isolated from Austrian vine-growing regions influence wine aroma differently and contain putative hybrids between Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Saccharomyces kudriavzevii. FEMS Yeast Res. 2007, 7, 953–965.

- Naumova, E.S.; Naumov, G.I.; Masneuf-Pomarède, I.; Aigle, M.; Dubourdieu, D. Molecular genetic study of introgression between Saccharomyces bayanus and S. cerevisiae. Yeast 2005, 22, 1099–1115.

- Groth, C.; Hansen, J.; Piskur, J. A natural chimeric yeast containing genetic material from three species. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1999, 49, 1933–1938.

- Naumov, G.I.; James, S.A.; Naumova, E.S.; Louis, E.J.; Roberts, I.N. Three new species in the Saccharomyces sensu stricto complex: Saccharomyces cariocanus, Saccharomyces kudriavzevii and Saccharomyces mikatae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2000, 50, 1931–1942.

- Sampaio, J.P.; Gonçalves, P. Natural populations of Saccharomyces kudriavzevii in Portugal are associated with oak bark and are sympatric with S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 2144–2152.