Under detrimental conditions such as those found during wine fermentation, yeast populations need to promote adaptive responses in order to survive in this harsh environment. Wine yeast has developed a plethora of genetic mechanisms to adapt to the wine niche, including variation of the copy number of certain genes, structural rearrangements, HGT or interspecific hybridization. From this set of genomic adaptations, structural variations leading to duplications of genes, chromosomic segments, full chromosomes or even the complete genome are the major cause of adaptation [133,144]. Besides its great impact by changing dosage, this structural variation can be the substrate for evolution and even the generation of new genes [145].

1. Introduction

Since ancient times, humans have employed the ability of the yeast, mainly

Saccharomyces cerevisiae to transform sugars into ethanol and several desirable compounds in order to produce foods and beverages of which wine and beer are the best-known products obtained from this process [

1,

2,

3]. Somehow, the use of wine yeasts by humans in fermentative processes during millennia could be considered as an unaware directed evolution process.

S. cerevisiae is the most extensively studied yeast belonging to

Saccharomyces genus which is currently formed by eight species, some of them related to industrial environments while others are exclusively located in natural environments such as wild forest [

4,

5].

Saccharomyces cerevisiae is very prone to deal with the stresses encountered in the main industrial niches such as wine and beer, such as osmotic stress, high ethanol levels, temperature, low pH, anaerobiosis, among others [

3,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

S. cerevisiae dominance is mainly due to its huge ability to convert a plethora of sugars into ethanol and CO

2, the latter acting as a potent antimicrobial compound to which

S. cerevisiae is quite resistant [

12]. In this sense,

S. cerevisiae presents the ability to make and accumulate ethanol even in aerobic conditions, as a consequence of the so-called Crabtree effect [

13]. This enhanced fermentative activity likely resulted from a major event in the genetic evolution of this yeast lineage, the whole genome duplication (WGD) event which enabled

S. cerevisiae to have an increased glycolytic flux [

14]. The so-called “make–accumulate–consume” strategy has been widely proposed by several authors as an ecological advantage of

S. cerevisiae to outcompete other microorganisms [

15,

16] and once competitors are overcome, the ethanol can be used in aerobic respiration [

17].

Nowadays, several commercial yeast strains are available for each industrial application [

18]. These industrial strains are genetically and phenotypically divergent from their wild counterparts [

5,

19] and, with very few exceptions, industrial strains can be grouped into several lineages which correlate with their application in the industry [

3,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Adaptation to harsh environments such as winemaking conditions can occur through smaller and/or larger genetic changes [

27,

29,

30]. Small-scale changes including insertions, deletions and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that may generate alteration in the gene expression and/or in the functionality of the encoded protein [

12,

20,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. Larger changes such as chromosomal rearrangements (duplications, translocations, and inversions) which may alter the genomic expression through changes in the genetic environment and copy number variations (CNV) which modify the dosage of a given gene [

19,

36]. Furthermore, interspecific hybridization can generate new genetic combinations through introgression and horizontal gene transfer events that could not be achieved through small-scale changes such as SNPs. Indeed, SNPs are only a small proportion of the genetic changes involved in adaptation [

37] likely due to the fact that adaptation to harsh niches needs to be fast in order to produce drastic changes in the phenotype, and these changes are difficult to acquire with a single nucleotide change.

2. Sugar Transporters (HXT3 and FSY1)

The ability to consume fructose in wine yeast is crucial at the end of fermentation in order to maintain good fermentation rates and therefore to reach dryness. The transport of hexoses in S. cerevisiae occurs by facilitated diffusion carriers encoded by different genes, some of them belonging to HXT family [39]. In S. cerevisiae, from the 17 HXT genes, only seven of them (HXT1–HXT7) are needed to grow on glucose or fructose [40].

In the last decade, the sequencing of the wine yeast EC1118 enabled the identification of three large chromosomal regions, A, B and C acquired through horizontal gene transfer (HGT) independently from different yeast species [

46]. Recently, the distant species

Torulaspora microellipsoides has been identified as the donor source of region C [

47]. This region contains 19 genes, including

FSY1, which codes a high-affinity fructose transporter that may present an advantage when fructose concentration is higher than glucose at the end of the fermentation [

48]. Recent work has shown that this region is widespread in both wine and Flor yeast [

3].

In wine yeast, fructose utilization is crucial in order to maintain a high fermentative rate at the end of the process and lead the wines to dryness [

41], and the strict protocols of wine yeast selection have contributed to the fixation of beneficial alleles in this environment. Flor yeast, when are in the velum form, develop an oxidative metabolism in which the main fermentable carbon source available is the fructose, therefore the acquisition of this fructophilic phenotype may be also beneficial [

48,

49].

3. Cysteine-S-β-lyase IRC7

IRC7 encodes a cysteine-S-β-lyase enzyme involved in the production of thiols in wines [

50,

51]. This gene presents two different alleles, a complete allele (

IRC7F) and a shorter version (

IRC7S) that has a deletion of 38-bp and provokes the expression of a truncated gene [

50]. This deletion produces a truncated protein of about 340 amino acids (aa) instead of the usual 400 aa, which generates an enzyme with lower β-lyase activity [

50].

Curiously, the short version of the enzyme is widespread among commercial wine yeast [

50,

52,

53,

54]. In fact, an analysis of the prevalence of

IRC7S in 223

S. cerevisiae strains showed that 88% of the studied strains bear the truncated

IRC7 allele [

52].

The reason why this truncated version of

IRC7 has been selected in the wine clade remains unclear, even more so when taking into account that the

IRC7F allele is strongly related with the production of desired aromas in wine; however, this is likely related to its biological role in yeast. It has been proposed a role of

IRC7F on cysteine homeostasis [

56], thus a complete

IRC7 may affect the availability of the intracellular cysteine pool and consequently compromise glutathione production. Therefore, due to the paramount role of the sulphur assimilation pathway in oxidative stress protection in wine fermentation,

IRC7s may have a role in this process [

6,

7]. This hypothesis was supported by other work in which authors observed less oxidative damage in strains harboring the short version in an oxidative-stress shock assay [

53].

4. Sulphite Resistance

Sulphite resistance is a paramount trait in wine yeasts due to the use of this compound in wineries as antioxidant and microbial inhibitor [

8,

57].

Saccharomyces species have evolved to adapt to the stress produced by sulphite by different mechanisms, which include an increase in acetaldehyde levels, which binds to SO

32−, the regulation of the sulphite uptake pathway, and the detoxification of sulphite through the plasma membrane pump encoded by the

SSU1 gene [

8]. Wine strains are significantly more resistant to SO

2 than other strains, mainly laboratory strains, and this is due to the evolution of a human-made environment for industrial production.

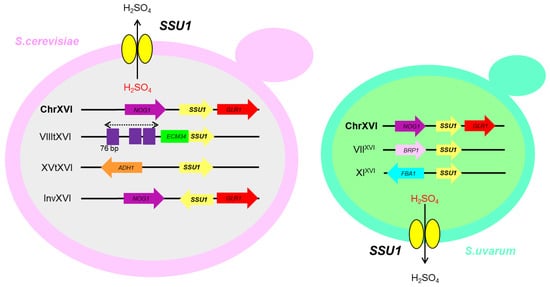

Figure 2 shows the different large chromosomal changes that have been described and linked to higher expression levels of the

SSU1 gene and, therefore to higher sulphite tolerance [

58,

59,

60].

Figure 2. Schematic view of chromosomal rearrangements identified in sulphite-resistant strains of S. cerevisiae and S. uvarum species. VIIItXVI was generated by the homology among the promoters of ECM34 and SSU1 genes. Several 76-bp (in purple) repetitions were found in the promoters, together with a positive correlation between the number of 76-bp repeats and sulfite resistance. XVtXVI involves the ADR1 and FZF1 binding sites of the promoter of ADH1 and SSU1 genes, respectively. InvXVI was produced by microhomology between the sequences of the regulatory regions of the genes SSU1 and GCR1 genes. The translocations found in S. uvarum, VIIXVI and XIXVI, are likely mediated by microhomology regions between BRP1-SSU1 and FBA1-SSU1, respectively.

These results point out to the strong selective pressure cause by sulphite in human-made environments and SSU1 gene promoter region is a hotspot for evolutionary processes at different taxonomic levels. In fact, the continuous discovering of different CR linked to sulphite tolerance in S. cerevisiae and more recently in S. uvarum could indicate that probably in other species present in the initial stage of wine fermentation such as Hanseniospora uvarum, Metschnikowia pulcherrima, Brettanomyces sp. among others, may exist also some sulphite detoxification mechanism. Further research on CR involving these species could be valuable and interesting.

5. Copper Tolerance

The copper-based fungicides namely “Bordeaux mixture” have been used traditionally in vineyards [

65]. However, copper is a toxic compound for several organisms including yeast. Yeasts have developed adaptive mechanisms in order to eliminate copper excesses, but when the intracellular concentrations are elevated can lead to cell death. To overcome this issue, metallothioneins, a class of low molecular weight molecules rich in cysteine residues are able to bind to copper ions to avoid their lethal effects [

66]. In

S. cerevisiae, the

CUP1 gene is the most representative member of this group of metallothioneins [

10,

67]. Wine strains usually present CNV of this gene with an increase dosage because this higher number of

CUP1 copies exert an effective protective mechanism against the copper-based fungicides. Some studies have proposed a positive correlation between higher CNV of

CUP1 gene and copper resistance as an adaptation strategy [

10,

22,

68,

69].

Furthermore, it has been identified a promoter variant in

CUP1 gene in the wine yeast strain EC1118 which is beneficial when dealing stress and indicates that, together with the increase in CNV, modulation of the expression of

CUP1 is another adaptation mechanism in yeast [

72]. In an experimental laboratory evolution work under the presence of copper, 27 of the 34 copper-adapted lines obtained during the evolution process showed an increase in CNV of

CUP1 gene through tandem duplication or aneuploidy of chromosome VIII [

73].

6. Oligopeptide Uptake: FOT Genes

Yeasts require nitrogen in order to construct some other essential molecules such as proteins and DNA and, thus, nitrogen is one of the key regulators in yeast. During fermentation, ammonium and free amino acids are the main nitrogen sources although some other secondary sources, namely oligopeptides and polypeptides, also contribute to the nitrogen levels [

74]. Oligopeptide transport in yeast is carried out by several proton-coupled symporters depending on the peptide length. The proton-dependent Oligopeptide Transporter PTR2 is the best-described transporter of di- and tripeptides together with DAL5, which also transports dipeptides [

75,

76]. OPT1 and OPT2, Oligopeptide Transport family members, are involved in the uptake of tetra- and pentapetides (OPT1) [

77,

78]. The horizontally acquired Region C from

T. microellipsoides, first identified in the wine yeast EC1118 [

46], also contains the genes

FOT1–

2 encoding for oligopeptide transporters, which considerable broaden the range of oligopeptides transported by PTR2 and DAL5 [

79]. Region C, and its rearrangements, are frequent among wine yeast and, even though gene losses and conversion within FOT genes are common, they are very well conserved among the genes of the region C, indicating a possible evolutionary advantage [

47,

80].

Besides FOT genes, several genes from the newly acquired regions present putative nitrogen-related functions [

46]. Furthermore, other introgressions from

S. kudriavzeviii and, mainly,

S. eubayanus were observed in

S. uvarum wine strains [

84]. All the introgressed regions located in chromosome II contained

ASP1 gene encoding the cytosolic L-asparaginase that degrades asparagine to be used as a nitrogen source [

85]. These genes may be an adaptive advantage taking into account that nitrogen can be limited in grape must. These results may indicate the concerted evolution of wine yeast genome associated with nitrogen utilization as recently suggested [

86]. As proposed, in non-limiting conditions, efficiency enhancing mutations cannot be fixed in well-mixed populations because the individuals without these beneficial changes have equal availability of resources compared with those carrying the efficiency enhancing mutations [

87]. However, in winemaking conditions where nitrogen can be limited, yeast carrying efficiency enhancing mutations have an advantage and thus, these changes can be selected in the population [

86].

7. Biofilm Formation: FLO Genes

Flor strains, which are involved in sherry wine production, are able to form a biofilm on the wine surface when fermentation is finished and change their metabolism from fermentative to oxidative in the presence of ethanol and low amounts of fermentable sugar [24,88,89]. Although flor yeasts are closely related to the wine strains [90], their unique life style have rendered their genetic structure more complex. Recently, genomic analysis stated that flor yeasts are an independent clade that emerged from the wine group through a relatively recent bottleneck event [45].

The ability to form a biofilm is largely dependent on the acquisition of two changes in the FLO11 gene [93], which encodes for hydrophobic cell wall glycoprotein that regulates cell adhesion, pseudohyphae, chronological aging and biofilm formation [94,95,96]. The first change was a 111-nt deletion within the promoter region of FLO11, which led to an increased expression [93,97]. This deletion is characteristic of Spanish, French, Italian, and Hungarian sherry strains [90].

Furthermore, FLO11, like the majority of the genes encoding cell wall proteins, contain intragenic tandem repeats [98]. In this regard, rearrangement in the central tandem repeat section of the ORF was responsible for producing a more hydrophobic FLO11, increasing the capacity of the yeast cells to adhere to each other [93,99]. However, the expanded FLO11 allele present in wild flor yeasts is highly unstable under non-selective conditions [99].

8. Inactivation of Aquaporin Genes

Water homeostasis is needed for osmoregulation and many other aspects of yeast life and is often associated with the presence of functional aquaporins (AQY) [

101]. The loss of function of the aquaporins

AQY1 and

AQY2 represents a case of adaptive mechanism by inactivation in wine strains, resulting in an advantage fitness in high-osmolarity environments [

102,

103]. Several deletions or mutations, which lead to premature stop codons, have been observed in AQY genes of wine strains. Aquaporins are crucial for the survival in freeze-thaw environments, such as those founded in natural niches, however, inactivation of both genes provides an increased fitness on high-sugar substrates such as wine fermentation, which could avoid or make more difficult the migration between environmental niches promoting ecological speciation [

102,

104].

9. Interspecific Hybridization

Hybridization between different species is a phenomenon that occurred in all kingdoms of life, which frequently leads to infertile individuals [

106]. This process has played a paramount role in the evolution of eukaryotes by generating new phenotypic diversity involved in the adaptation to new environments among divergent lineages [

107,

108,

109].

Hybrids may have some advantages over parental strains in wine fermentation such as higher resistance to various stresses occurring during fermentation [

106,

110,

111,

112,

113,

114]. In this sense,

S. kudriavzevii and

S. uvarum are more cryotolerant compared with

S. cerevisiae wine strains, while

S. cerevisiae is more tolerant to high levels of ethanol [

115,

116,

117,

118,

119]. Natural hybrids can exhibit interesting traits from both parentals, being able to grow under ethanol and low temperature stress [

113,

120] or produce other desirable aromas such as the fruity thiol 4-mercapto-4-methylpentan-2-one [

121,

122]. The analysis of natural hybrid of

S. cerevisiae ×

S. uvarum isolated from wine [

80] shows better performance in cold fermentations, higher glycerol production, lower acetic acid production and increased production of several interesting aroma compounds.

In the wine niche, hybrids between

Saccharomyces genus species have been naturally found as an adaptation mechanism to human-made fermentative environments. Hybridization could be considered as an adaptation strategy due to their abundance. However, it is also plausible that the harsh environments trigger hybridization events [

123]. Natural hybrids between

S. cerevisiae and

S. kudriavzevii are commonly found in cold-climate European countries where these hybrids even outcompete

S. cerevisiae during fermentation due to low temperature fermentations [

110,

120,

124,

125].

S. cerevisiae ×

S. uvarum hybrids and the triple hybrid

S. cerevisiae ×

S. uvarum ×

S. kudriavzevii have been naturally isolated from wine and cider environments [

110,

126,

127]. Curiously,

S. kudriavzevii has not been isolated from fermentative environments, thus, it remains unclear where these hybrids are generated [

124,

128,

129].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/microorganisms10091811