Under detrimental conditions such as those found during wine fermentation, yeast populations need to promote adaptive responses in order to survive in this harsh environment. Wine yeast has developed a plethora of genetic mechanisms to adapt to the wine niche, including variation of the copy number of certain genes, structural rearrangements, horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or interspecific hybridization. From this set of genomic adaptations, structural variations leading to duplications of genes, chromosomic segments, full chromosomes or even the complete genome are the major cause of adaptation [133,144]. Besides its great impact by changing dosage, this structural variation can be the substrate for evolution and even the generation of new genes [145].

- wine yeast

- chromosomal rearrangements

- copy number variation

- hybridization

1. Introduction

2. Sugar Transporters (HXT3 and FSY1)

The ability to consume fructose in wine yeast is crucial at the end of fermentation in order to maintain good fermentation rates and therefore to reach dryness. The transport of hexoses in S. cerevisiae occurs by facilitated diffusion carriers encoded by different genes, some of them belonging to HXT family [38][39]. In S. cerevisiae, from the 17 HXT genes, only seven of them (HXT1–HXT7) are needed to grow on glucose or fructose [39][40].

In the last decade, the sequencing of the wine yeast EC1118 enabled the identification of three large chromosomal regions, A, B and C acquired through horizontal gene transfer (HGT) independently from different yeast species [40][46]. Recently, the distant species Torulaspora microellipsoides has been identified as the donor source of region C [41][47]. This region contains 19 genes, including FSY1, which codes a high-affinity fructose transporter that may present an advantage when fructose concentration is higher than glucose at the end of the fermentation [42][48]. IRecent has been work has shown that this region is widespread in both wine and Flor yeast [3]. In wine yeast, fructose utilization is crucial in order to maintain a high fermentative rate at the end of the process and lead the wines to dryness [43][41], and the strict protocols of wine yeast selection have contributed to the fixation of beneficial alleles in this environment. Flor yeast, when are in the velum form, develop an oxidative metabolism in which the main fermentable carbon source available is the fructose, therefore the acquisition of this fructophilic phenotype may be also beneficial [42][44][48,49].3. Cysteine-S-β-lyase IRC7

IRC7 encodes a cysteine-S-β-lyase enzyme involved in the production of thiols in wines [45][46][50,51]. This gene presents two different alleles, a complete allele (IRC7F) and a shorter version (IRC7S) that has a deletion of 38-bp and provokes the expression of a truncated gene [45][50]. This deletion produces a truncated protein of about 340 amino acids (aa) instead of the usual 400 aa, which generates an enzyme with lower β-lyase activity [45][50]. Curiously, the short version of the enzyme is widespread among commercial wine yeast [45][47][48][49][50,52,53,54]. In fact, an analysis of the prevalence of IRC7S in 223 S. cerevisiae strains showed that 88% of the studied strains bear the truncated IRC7 allele [47][52]. The reason why this truncated version of IRC7 has been selected in the wine clade remains unclear, even more so when taking into account that the IRC7F allele is strongly related with the production of desired aromas in wine; however, this is likely related to its biological role in yeast. It has been proposed a role of IRC7F on cysteine homeostasis [50][56], thus a complete IRC7 may affect the availability of the intracellular cysteine pool and consequently compromise glutathione production. Therefore, due to the paramount role of the sulphur assimilation pathway in oxidative stress protection in wine fermentation, IRC7s may have a role in this process [6][7][6,7]. This hypothesis was supported by other work in which scautholars observed less oxidative damage in strains harboring the short version in an oxidative-stress shock assay [48][53].4. Sulphite Resistance

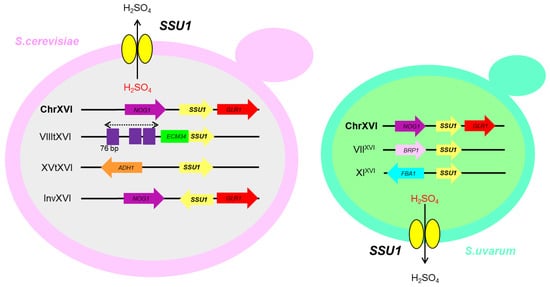

Sulphite resistance is a paramount trait in wine yeasts due to the use of this compound in wineries as antioxidant and microbial inhibitor [8][51][8,57]. Saccharomyces species have evolved to adapt to the stress produced by sulphite by different mechanisms, which include an increase in acetaldehyde levels, which binds to SO32−, the regulation of the sulphite uptake pathway, and the detoxification of sulphite through the plasma membrane pump encoded by the SSU1 gene [8]. Wine strains are significantly more resistant to SO2 than other strains, mainly laboratory strains, and this is due to the evolution of a human-made environment for industrial production. Figure 1 2 shows the different large chromosomal changes that have been described and linked to higher expression levels of the SSU1 gene and, therefore to higher sulphite tolerance [52][53][54][58,59,60].

5. Copper Tolerance

6. Oligopeptide Uptake: FOT Genes

Yeasts require nitrogen in order to construct some other essential molecules such as proteins and DNA and, thus, nitrogen is one of the key regulators in yeast. During fermentation, ammonium and free amino acids are the main nitrogen sources although some other secondary sources, namely oligopeptides and polypeptides, also contribute to the nitrogen levels [62][74]. Oligopeptide transport in yeast is carried out by several proton-coupled symporters depending on the peptide length. The proton-dependent Oligopeptide Transporter PTR2 is the best-described transporter of di- and tripeptides together with DAL5, which also transports dipeptides [63][64][75,76]. OPT1 and OPT2, Oligopeptide Transport family members, are involved in the uptake of tetra- and pentapetides (OPT1) [65][66][77,78]. The horizontally acquired Region C from T. microellipsoides, first identified in the wine yeast EC1118 [40][46], also contains the genes FOT1–2 encoding for oligopeptide transporters, which considerable broaden the range of oligopeptides transported by PTR2 and DAL5 [67][79]. Region C, and its rearrangements, are frequent among wine yeast and, even though gene losses and conversion within FOT genes are common, they are very well conserved among the genes of the region C, indicating a possible evolutionary advantage [41][68][47,80]. Besides FOT genes, several genes from the newly acquired regions present putative nitrogen-related functions [40][46]. Furthermore, other introgressions from S. kudriavzeviii and, mainly, S. eubayanus were observed in S. uvarum wine strains [69][84]. All the introgressed regions located in chromosome II contained ASP1 gene encoding the cytosolic L-asparaginase that degrades asparagine to be used as a nitrogen source [70][85]. These genes may be an adaptive advantage taking into account that nitrogen can be limited in grape must. These results may indicate the concerted evolution of wine yeast genome associated with nitrogen utilization as recently suggested [71][86]. As proposed, in non-limiting conditions, efficiency enhancing mutations cannot be fixed in well-mixed populations because the individuals without these beneficial changes have equal availability of resources compared with those carrying the efficiency enhancing mutations [72][87]. However, in winemaking conditions where nitrogen can be limited, yeast carrying efficiency enhancing mutations have an advantage and thus, these changes can be selected in the population [71][86].7. Biofilm Formation: FLO Genes

Flor strains, which are involved in sherry wine production, are able to form a biofilm on the wine surface when fermentation is finished and change their metabolism from fermentative to oxidative in the presence of ethanol and low amounts of fermentable sugar [24][73][74][24,88,89]. Although flor yeasts are closely related to the wine strains [75][90], their unique life style have rendered their genetic structure more complex. Recently, genomic analysis stated that flor yeasts are an independent clade that emerged from the wine group through a relatively recent bottleneck event [76][45].

The ability to form a biofilm is largely dependent on the acquisition of two changes in the FLO11 gene [77][93], which encodes for hydrophobic cell wall glycoprotein that regulates cell adhesion, pseudohyphae, chronological aging and biofilm formation [78][79][80][94,95,96]. The first change was a 111-nt deletion within the promoter region of FLO11, which led to an increased expression [77][81][93,97]. This deletion is characteristic of Spanish, French, Italian, and Hungarian sherry strains [75][90].

Furthermore, FLO11, like the majority of the genes encoding cell wall proteins, contain intragenic tandem repeats [82][98]. In this regard, rearrangement in the central tandem repeat section of the ORF was responsible for producing a more hydrophobic FLO11, increasing the capacity of the yeast cells to adhere to each other [77][83][93,99]. However, the expanded FLO11 allele present in wild flor yeasts is highly unstable under non-selective conditions [83][99].