| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jianliang Zhou | -- | 2358 | 2022-09-27 08:11:42 | | | |

| 2 | Sirius Huang | Meta information modification | 2358 | 2022-09-28 03:38:08 | | |

Video Upload Options

Valve replacement is the mainstay of treatment for end-stage valvular heart disease, but varying degrees of defects exist in clinically applied valve implants. A mechanical heart valve requires long-term anti-coagulation, but the formation of blood clots is still inevitable. A biological heart valve eventually decays following calcification due to glutaraldehyde cross-linking toxicity and a lack of regenerative capacity. The goal of tissue-engineered heart valves is to replace normal heart valves and overcome the shortcomings of heart valve replacement commonly used in clinical practice. Surface biofunctionalization has been widely used in various fields of research to achieve functionalization and optimize mechanical properties.

1. Introduction

2. Biofunctionalization of the Tissue Engineered Heart Valves

2.1. Non-Glutaraldehyde Cross-Linking

| Cross-Linking Agent | Advantages Compared with GLUT Treatment | Cross-Linking Mechanisms |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

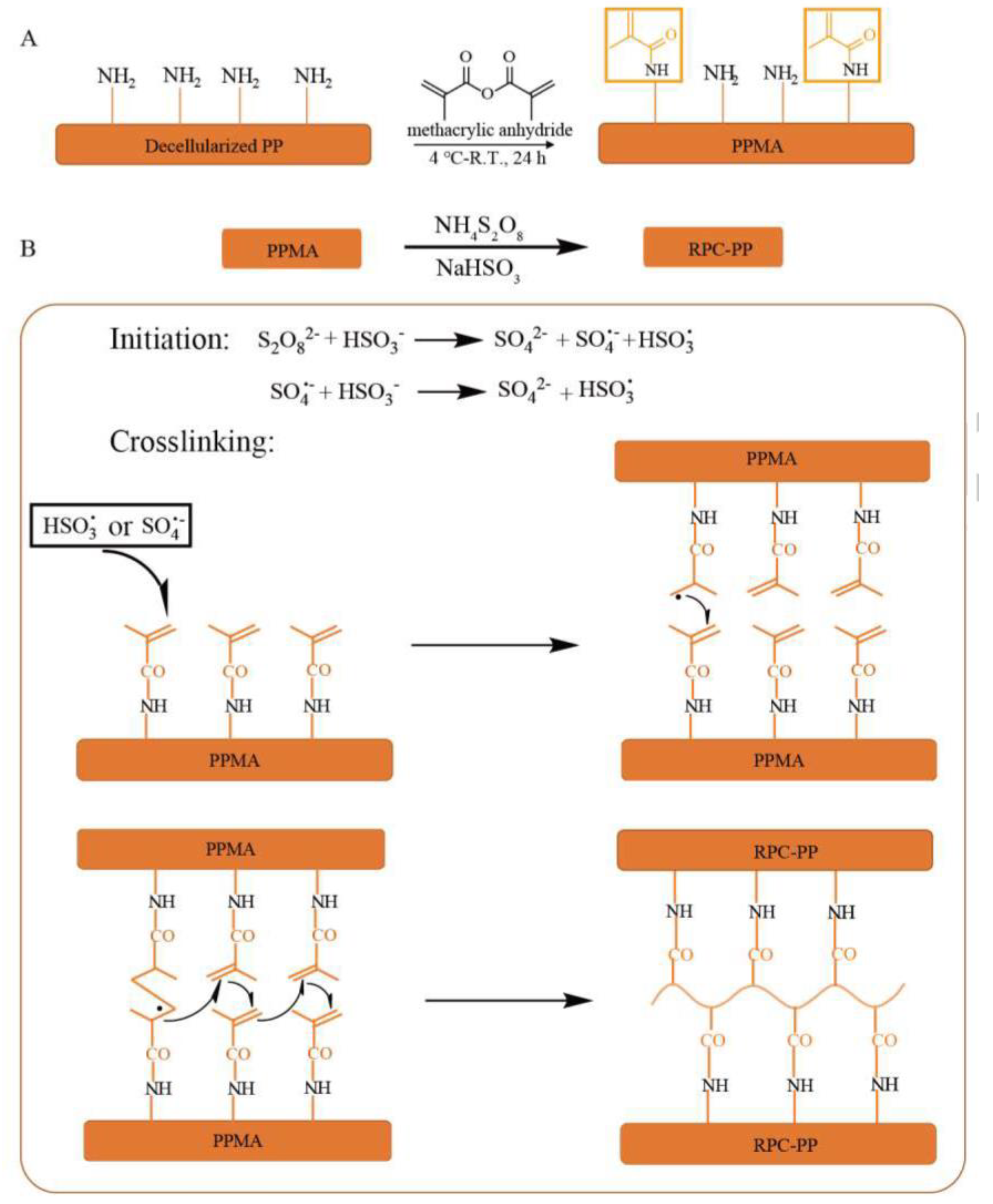

| Methacrylic anhydride | Improve the biocompatibility and anti-calcification performance | Radicals react with vinyl on collagen | [26][27][28] |

| Procyanidins | Anti-calcification | Hydrogen bond | [29][30] |

| Curcumin | Anti-calcification | Hydrogen bond | [31] |

| Quercetin | Increasing significantly the ultimate tensile strength and anti-calcification |

Hydrogen bond | [32] |

| 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide | Improving the biocompatibility | Amide and ester bond formation of side groups |

[41] |

| (3-glycidyloxypropyl) trimethoxysilane | Improving the cytocompatibility, endothelialization, hemocompatibility, and anti-calcification properties |

Epoxy reacts with amino groups; inorganic polymerization | [42] |

| Dialdehyde pectin | Enhancing anti-calcification and anti- coagulation |

Schiff base reaction | [43] |

| Alginate (oxidized alginate) | Improving the cytocompatibility, hemocompatibility, and anti-calcification properties |

Amino reaction with carboxyl groups | [44] |

| Rose Bengal | Less cytotoxicity and better endothelialization potential |

Photoinduced cross-linking | [45] |

| Triglycidyl amine | Anti-calcification | Reactive epoxy reacts with amine groups | [46][47][48][49] |

2.2. Modification Strategies after Decellularization

2.2.1. Hydrogel Coating

| Composition of Hydrogels | Advantages of Hydrogels | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| VEGF-Loaded hyaluronic acid hydrogel |

Improve adhesion and growth potential, with less platelet adhesion and less calcification | Cross-linking the hydroxyl group of hyaluronic acid with the epoxide of BDDE |

[62] |

| VEGF-loaded elastin hydrogel | Improve endothelialization potential | Cross-linking reaction between the amine groups of soluble elastin and hexamethylene diisocyanate | [63] |

| Sulfobetaine methacrylate and methacrylated hyaluronic acid | Improve endothelialization and anti-calcification properties |

Radical polymerization | [65] |

| Hyaluronic acid and hydrophilic polyacrylamide |

Improve endothelialization, biocompatibility, and anticalcifification properties | Ionic and chemical Cross-linking |

[67] |

| SDF-1a-loaded MMP degradable hydrogel | Promote cell growth and mediate the tissue remodeling |

Michael-type addition reaction | [68] |

| Polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane–polyethylene glycol hybrid hydrogel | Have anti-calcification potential | Formation of hydrogel network connecting POSS and MMP peptide using four-arm PEG-MAL | [69] |

| Chondroitin sulfate hydrogel |

Improve endothelialization and shield against deterioration | Polymerization under UV lamps | [70] |

2.2.2. Cross-Linked with Nanocomposite

| Composition of Nanocomposite | Advantages of Nanocomposite | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| TGF-β1-loaded polyethylene glycol nanoparticles | Advantageous biocompatibility | Combining with PEG nanoparticles by carbodiimide | [78] |

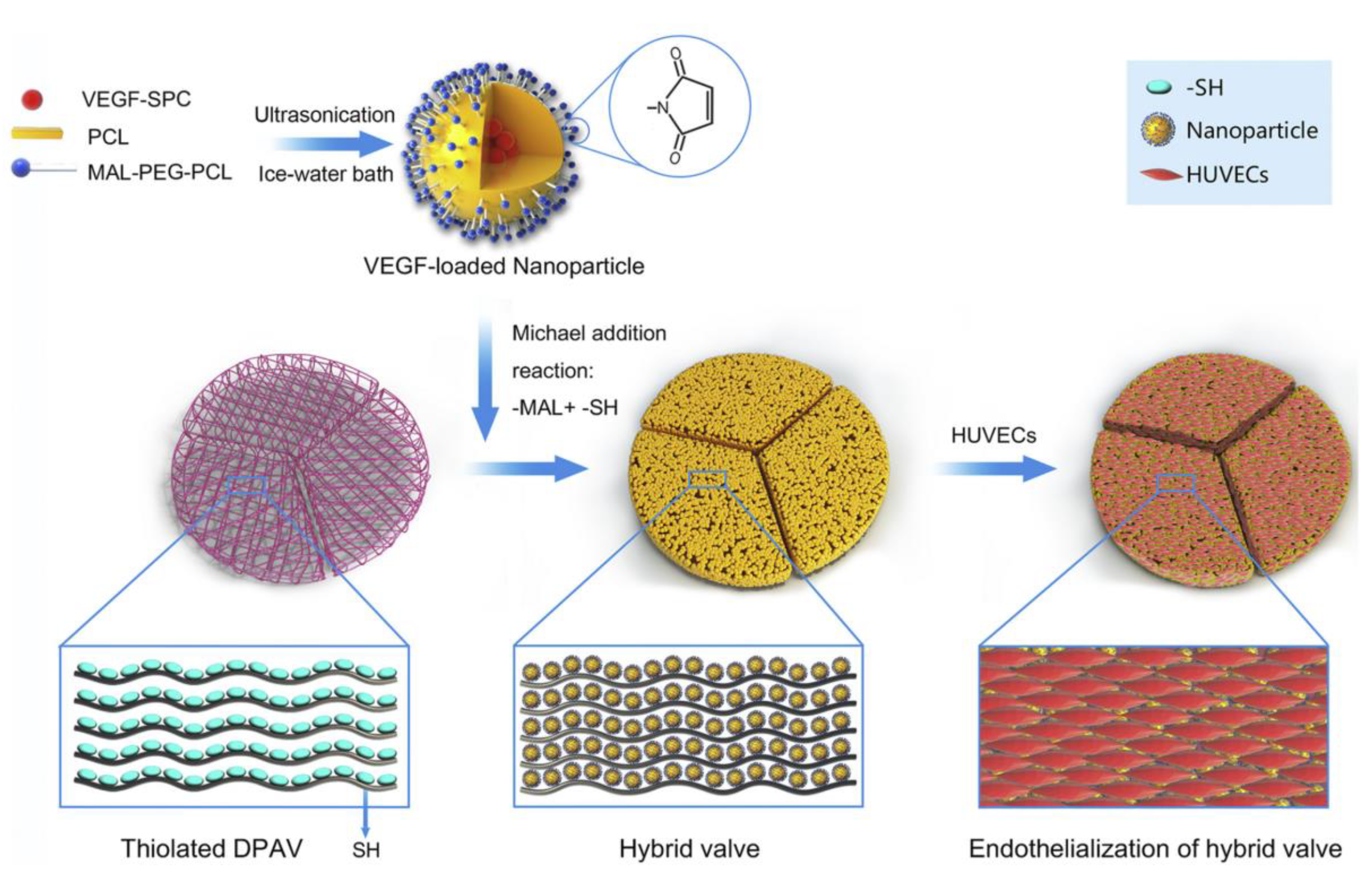

| VEGF-loaded polycaprolactone nanoparticles | Acceleration of endothelialization | Michael addition reaction | [79] |

| RBC-based rapamycin and atorvastatin calcium-loaded poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid nanoparticles | Anticoagulation, anti-inflammation, anti-calcification, and endothelialization properties | Amidation reaction | [80] |

| OPG-loaded polycaprolactone nanoparticles | Anti-calcification | Michael addition reaction | [84] |

| Rivaroxaban-loaded nanogels | Acceleration of endothelialization and antithrombogenicity | Self-assembly | [85] |

| Polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane- nanocomposite |

Acceleration of endothelialization potential | Reaction of the silanol groups of cyclohexanechlorohydrine-functionalized POSS with isocyanate |

[86][87][88] |

References

- Lindroos, M.; Kupari, M.; Heikkilä, J.; Tilvis, R. Prevalence of aortic valve abnormalities in the elderly: An echocardiographic study of a random population sample. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1993, 21, 1220–1225.

- Lim, W.Y.; Lloyd, G.; Bhattacharyya, S. Mechanical and surgical bioprosthetic valve thrombosis. Heart 2017, 103, 1934–1941.

- Vahanian, A.; Beyersdorf, F.; Praz, F.; Milojevic, M.; Baldus, S.; Bauersachs, J.; Capodanno, D.; Conradi, L.; De Bonis, M.; De Paulis, R.; et al. Corrigendum to: 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease: Developed by the Task Force for the management of valvular heart disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 561–632.

- Heidenreich, P.A.; Bozkurt, B.; Aguilar, D.; Allen, L.A.; Byun, J.J.; Colvin, M.M.; Deswal, A.; Drazner, M.H.; Dunlay, S.M.; Evers, L.R.; et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 79, e263–e421.

- Tasoudis, P.T.; Varvoglis, D.N.; Vitkos, E.; Mylonas, K.S.; Sá, M.P.; Ikonomidis, J.S.; Caranasos, T.G.; Athanasiou, T. Mechanical versus bioprosthetic valve for aortic valve replacement: Systematic review and meta-analysis of reconstructed individual participant data. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2022, 62, ezac268.

- Sewell-Loftin, M.K.; Chun, Y.W.; Khademhosseini, A.; Merryman, W.D. EMT-Inducing Biomaterials for Heart Valve Engineering: Taking Cues from Developmental Biology. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2011, 4, 658–671.

- Sacks, M.S.; Schoen, F.J.; Mayer, J.E. Bioengineering Challenges for Heart Valve Tissue Engineering. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2009, 11, 289–313.

- Cannegieter, S.C.; Rosendaal, F.R.; Briët, E. Thromboembolic and bleeding complications in patients with mechanical heart valve prostheses. Circulation 1994, 89, 635–641.

- Schoen, F.J.; Levy, R.J. Calcification of Tissue Heart Valve Substitutes: Progress Toward Understanding and Prevention. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2005, 79, 1072–1080.

- Boroumand, S.; Asadpour, S.; Akbarzadeh, A.; Faridi-Majidi, R.; Ghanbari, H. Heart valve tissue engineering: An overview of heart valve decellularization processes. Regen. Med. 2018, 13, 41–54.

- Nachlas, A.L.; Li, S.; Davis, M.E. Developing a Clinically Relevant Tissue Engineered Heart Valve—A Review of Current Approaches. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2017, 6, 1700918.

- Bezuidenhout, D.; Oosthuysen, A.; Human, P.; Weissenstein, C.; Zilla, P. The effects of cross-link density and chemistry on the calcification potential of diamine-extended glutaraldehyde-fixed bioprosthetic heart-valve materials. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2009, 54, 133–140.

- Nimni, M.E.; Deshmukh, A.; Deshmukh, K. Synthesis of aldehydes and their interactions during the in vitro aging of collagen. Biochemistry 1971, 10, 2337–2342.

- Carpentier, A.; Lemaigre, G.; Robert, L.; Carpentier, S.; Dubost, C. Biological factors affecting long-term results of valvular heterografts. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1969, 58, 467–483.

- Golomb, G.; Schoen, F.J.; Smith, M.S.; Linden, J.; Dixon, M.; Levy, R.J. The role of glutaraldehyde-induced cross-links in calcification of bovine pericardium used in cardiac valve bioprostheses. Am. J. Pathol. 1987, 127, 122–130.

- Dahm, M.; Lyman, W.D.; Schwell, A.B.; Factor, S.M.; Frater, R.W. Immunogenicity of glutaraldehyde-tanned bovine pericardium. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1990, 99, 1082–1090.

- Everts, V.; van der Zee, E.; Creemers, L.; Beertsen, W. Phagocytosis and intracellular digestion of collagen, its role in turnover and remodelling. Histochem. J. 1996, 28, 229–245.

- Stein, P.D.; Wang, C.H.; Riddle, J.M.; Magilligan, D.J., Jr. Leukocytes, platelets, and surface microstructure of spontaneously degen-erated porcine bioprosthetic valves. J. Card. Surg. 1988, 3, 253–261.

- Siddiqui, R.F.; Abraham, J.R.; Butany, J. Bioprosthetic heart valves: Modes of failure. Histopathology 2009, 55, 135–144.

- Manji, R.A.; Menkis, A.H.; Ekser, B.; Cooper, D.K. Porcine bioprosthetic heart valves: The next generation. Am. Heart J. 2012, 164, 177–185.

- Sung, H.-W.; Hsu, C.-S.; Lee, Y.-S. Physical properties of a porcine internal thoracic artery fixed with an epoxy compound. Biomaterials 1996, 17, 2357–2365.

- Jorge-Herrero, E.; Fonseca, C.; Barge, A.; Turnay, J.; Olmo, N.; Fernández, P.; Lizarbe, M.; García-Páez, J. Biocompatibility and calcification of bovine pericardium employed for the construction of cardiac bioprostheses treated with different chemical crosslink methods. Artif Organs. 2010, 34, E168–E176.

- Damink, L.O.; Dijkstra, P.J.; Van Luyn, M.J.A.; Van Wachem, P.B.; Nieuwenhuis, P.; Feijen, J. In vitro degradation of dermal sheep collagen cross-linked using a water-soluble carbodiimide. Biomaterials 1996, 17, 679–684.

- Cao, H.; Xu, S.Y. EDC/NHS-crosslinked type II collagen-chondroitin sulfate scaffold: Characterization and in vitro evaluation. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2008, 19, 567–575.

- Ma, B.; Wang, X.; Wu, C.; Chang, J. Crosslinking strategies for preparation of extracellular matrix-derived cardiovascular scaffolds. Regen. Biomater. 2014, 1, 81–89.

- Jin, L.; Guo, G.; Jin, W.; Lei, Y.; Wang, Y. Cross-Linking Methacrylated Porcine Pericardium by Radical Polymerization Confers Enhanced Extracellular Matrix Stability, Reduced Calcification, and Mitigated Immune Response to Bioprosthetic Heart Valves. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 5, 1822–1832.

- Guo, G.; Jin, L.; Jin, W.; Chen, L.; Lei, Y.; Wang, Y. Radical polymerization-crosslinking method for improving extracellular matrix stability in bioprosthetic heart valves with reduced potential for calcification and inflammatory response. Acta Biomater. 2018, 82, 44–55.

- Xu, L.; Yang, F.; Ge, Y.; Guo, G.; Wang, Y. Crosslinking porcine aortic valve by radical polymerization for the preparation of BHVs with improved cytocompatibility, mild immune response, and reduced calcification. J. Biomater. Appl. 2021, 35, 1218–1232.

- Zhai, W.; Chang, J.; Lü, X.; Wang, Z. Procyanidins-crosslinked heart valve matrix: Anticalcification effect. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2009, 90, 913–921.

- Zhai, W.; Chang, J.; Lin, K.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Q.; Sun, X. Crosslinking of decellularized porcine heart valve matrix by procyanidins. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 3684–3690.

- Liu, J.; Li, B.; Jing, H.; Qin, Y.; Wu, Y.; Kong, D.; Leng, X.; Wang, Z. Curcumin-crosslinked acellular bovine pericardium for the application of calcification inhibition heart valves. Biomed. Mater. 2020, 15, 045002.

- Zhai, W.; Lü, X.; Chang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H. Quercetin-crosslinked porcine heart valve matrix: Mechanical properties, stability, anticalcification and cytocompatibility. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 389–395.

- Calero, P.; Jorge-Herrero, E.; Turnay, J.; Olmo, N.; de Silanes, I.L.; Lizarbe, M.; Maestro, M.; Arenaz, B.; Castillo-Olivares, J. Gelatinases in soft tissue biomaterials. Analysis of different crosslinking agents. Biomaterials 2002, 23, 3473–3478.

- Dewanjee, M.K.; Solis, E.; Lanker, J.; Mackey, S.T.; Lombardo, G.M.; Tidwell, C.; Ellefsen, R.D.; Kaye, M.P. Effect of diphosphonate binding to collagen upon inhibition of calcification and pro-motion of spontaneous endothelial cell coverage on tissue valve prostheses. ASAIO Trans. 1986, 32, 24–29.

- Jorge-Herrero, E.; Fernández, P.; Turnay, J.; Olmo, N.; Calero, P.; García, R.; Freile, I.; Castillo-Olivares, J. Influence of different chemical cross-linking treatments on the properties of bovine pericardium and collagen. Biomaterials 1999, 20, 539–545.

- Lovekamp, J.; Vyavahare, N. Periodate-mediated glycosaminoglycan stabilization in bioprosthetic heart valves. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2001, 56, 478–486.

- Sung, H.W.; Hsu, H.L.; Shih, C.C.; Lin, D.S. Cross-linking characteristics of biological tissues fixed with monofunctional or multi-functional epoxy compounds. Biomaterials 1996, 17, 1405–1410.

- Sung, H.W.; Chang, Y.; Chiu, C.T.; Chen, C.N.; Liang, H.C. Crosslinking characteristics and mechanical properties of a bovine peri-cardium fixed with a naturally occurring crosslinking agent. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1999, 47, 116–126.

- Jayakrishnan, A.; Jameela, S. Glutaraldehyde as a fixative in bioprostheses and drug delivery matrices. Biomaterials 1996, 17, 471–484.

- Van Wachem, P.B.; Brouwer, L.A.; Zeeman, R.; Dijkstra, P.J.; Feijen, J.; Hendriks, M.; Cahalan, P.T.; van Luyn, M.J. In vivo behavior of epoxy-crosslinked porcine heart valve cusps and walls. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2000, 53, 18–27.

- Park, S.-N.; Park, J.-C.; Kim, H.O.; Song, M.J.; Suh, H. Characterization of porous collagen/hyaluronic acid scaffold modified by 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide cross-linking. Biomaterials 2001, 23, 1205–1212.

- Yang, F.; He, H.; Xu, L.; Jin, L.; Guo, G.; Wang, Y. Inorganic-polymerization crosslinked tissue-siloxane hybrid as potential biomaterial for bioprosthetic heart valves. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2020, 109, 754–765.

- Hu, M.; Peng, X.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, X.; Cheng, C.; Yu, X. Dialdehyde pectin-crosslinked and hirudin-loaded decellularized porcine pericardium with improved matrix stability, enhanced anti-calcification and anticoagulant for bioprosthetic heart valves. Biomater. Sci. 2021, 9, 7617–7635.

- Liu, J.; Jing, H.; Qin, Y.; Li, B.; Sun, Z.; Kong, D.; Leng, X.; Wang, Z. Nonglutaraldehyde Fixation for off the Shelf Decellularized Bovine Pericardium in Anticalcification Cardiac Valve Applications. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 5, 1452–1461.

- Yang, F.; Xu, L.; Guo, G.; Wang, Y. Visible light-induced cross-linking of porcine pericardium for the improvement of endotheli-alization, anti-tearing, and anticalcification properties. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2022, 110, 31–42.

- Sacks, M.S.; Hamamoto, H.; Connolly, J.M.; Gorman, R.C.; Gorman, J.H., 3rd; Levy, R.J. In vivo biomechanical assessment of triglyc-idylamine crosslinked pericardium. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 5390–5398.

- Connolly, J.M.; Bakay, M.A.; Alferiev, I.S.; Gorman, R.C.; Gorman, J.H.; Kruth, H.S.; Ashworth, P.E.; Kutty, J.K.; Schoen, F.J.; Bianco, R.W.; et al. Triglycidyl Amine Crosslinking Combined with Ethanol Inhibits Bioprosthetic Heart Valve Calcification. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2011, 92, 858–865.

- Rapoport, H.S.; Connolly, J.M.; Fulmer, J.; Dai, N.; Murti, B.H.; Gorman, R.C.; Gorman, J.H.; Alferiev, I.; Levy, R.J. Mechanisms of the in vivo inhibition of calcification of bioprosthetic porcine aortic valve cusps and aortic wall with triglycidylamine/mercapto bisphosphonate. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 690–699.

- Connolly, J.M.; Alferiev, I.; Eidelman, N.; Sacks, M.; Palmatory, E.; Kronsteiner, A.; DeFelice, S.; Xu, J.; Ohri, R.; Narula, N.; et al. Triglycidylamine Crosslinking of Porcine Aortic Valve Cusps or Bovine Pericardium Results in Improved Biocompatibility, Biomechanics, and Calcification Resistance: Chemical and Biological Mechanisms. Am. J. Pathol. 2005, 166, 1–13.

- Steinhoff, G.; Stock, U.; Karim, N.; Mertsching, H.; Timke, A.; Meliss, R.R.; Pethig, K.; Haverich, A.; Bader, A. Tissue Engineering of Pulmonary Heart Valves on Allogenic Acellular Matrix Conduits: In Vivo Restoration of Valve Tissue. Circulation 2000, 102, Iii-50–Iii-55.

- Booth, C.; Korossis, S.A.; Wilcox, H.E.; Watterson, K.G.; Kearney, J.N.; Fisher, J.; Ingham, E. Tissue engineering of cardiac valve prostheses I: Development and histological char-acterization of an acellular porcine scaffold. J. Heart Valve Dis. 2002, 11, 457–462.

- Korossis, S.A.; Booth, C.; Wilcox, H.E.; Watterson, K.G.; Kearney, J.N.; Fisher, J.; Ingham, E. Tissue engineering of cardiac valve prostheses II: Biomechanical characterization of decellularized porcine aortic heart valves. J. Heart Valve Dis. 2002, 11, 463–471.

- Cebotari, S.; Mertsching, H.; Kallenbach, K.; Kostin, S.; Repin, O.; Batrinac, A.; Ciubotaru, A.; Haverich, A. Construction of autologous human heart valves based on an acellular allograft matrix. Circulation 2002, 106 (Suppl. 1), I-63–I-68.

- Simon, P.; Kasimir, M.; Seebacher, G.; Weigel, G.; Ullrich, R.; Salzer-Muhar, U.; Rieder, E.; Wolner, E. Early failure of the tissue engineered porcine heart valve SYNERGRAFT™ in pediatric patients. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2003, 23, 1002–1006.

- Mol, A.; van Lieshout, M.I.; Veen, C.G.D.-D.; Neuenschwander, S.; Hoerstrup, S.P.; Baaijens, F.P.; Bouten, C.V. Fibrin as a cell carrier in cardiovascular tissue engineering applications. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 3113–3121.

- Flanagan, T.C.; Sachweh, J.S.; Frese, J.; Schnöring, H.; Gronloh, N.; Koch, S.; Tolba, R.H.; Schmitz-Rode, T.; Jockenhoevel, S. In Vivo Remodeling and Structural Characterization of Fibrin-Based Tissue-Engineered Heart Valves in the Adult Sheep Model. Tissue Eng. Part A 2009, 15, 2965–2976.

- Masters, K.S.; Shah, D.N.; Leinwand, L.A.; Anseth, K.S. Crosslinked hyaluronan scaffolds as a biologically active carrier for valvular interstitial cells. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 2517–2525.

- Durst, C.A.; Cuchiara, M.P.; Mansfield, E.G.; West, J.L.; Grande-Allen, K.J. Flexural characterization of cell encapsulated PEGDA hydrogels with applications for tissue engineered heart valves. Acta Biomater. 2011, 7, 2467–2476.

- Tseng, H.; Cuchiara, M.L.; Durst, C.A.; Cuchiara, M.P.; Lin, C.J.; West, J.L.; Grande-Allen, K.J. Fabrication and Mechanical Evaluation of Anatomically-Inspirei Quasilaminate Hydrogel Structures with Layer-Specific Formulations. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2013, 41, 398–407.

- Jiang, H.; Campbell, G.; Boughner, D.; Wan, W.-K.; Quantz, M. Design and manufacture of a polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) cryogel tri-leaflet heart valve prosthesis. Med. Eng. Phys. 2004, 26, 269–277.

- Flanagan, T.C.; Wilkins, B.; Black, A.; Jockenhoevel, S.; Smith, T.J.; Pandit, A.S. A collagen-glycosaminoglycan co-culture model for heart valve tissue engineering applications. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 2233–2246.

- Lei, Y.; Deng, L.; Tang, Y.; Ning, Q.; Lan, X.; Wang, Y. Hybrid Pericardium with VEGF-Loaded Hyaluronic Acid Hydrogel Coating to Improve the Biological Properties of Bioprosthetic Heart Valves. Macromol. Biosci. 2019, 19, e1800390.

- Lei, L.; Tao, X.; Xie, L.; Hong, Z. Vascular endothelial growth factor-loaded elastin-hydrogel modification of the pericardium im-proves endothelialization potential of bioprosthetic heart valves. J. Biomater. Appl. 2019, 34, 451–459.

- Marinval, N.; Morenc, M.; Labour, M.-N.; Samotus, A.; Mzyk, A.; Ollivier, V.; Maire, M.; Jesse, K.; Bassand, K.; Niemiec-Cyganek, A.; et al. Fucoidan/VEGF-based surface modification of decellularized pulmonary heart valve improves the antithrombotic and re-endothelialization potential of bioprostheses. Biomaterials 2018, 172, 14–29.

- Luo, Y.; Huang, S.; Ma, L. Zwitterionic hydrogel-coated heart valves with improved endothelialization and anti-calcification properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 128, 112329.

- Jahnavi, S.; Kumary, T.; Bhuvaneshwar, G.; Natarajan, T.; Verma, R. Engineering of a polymer layered bio-hybrid heart valve scaffold. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2015, 51, 263–273.

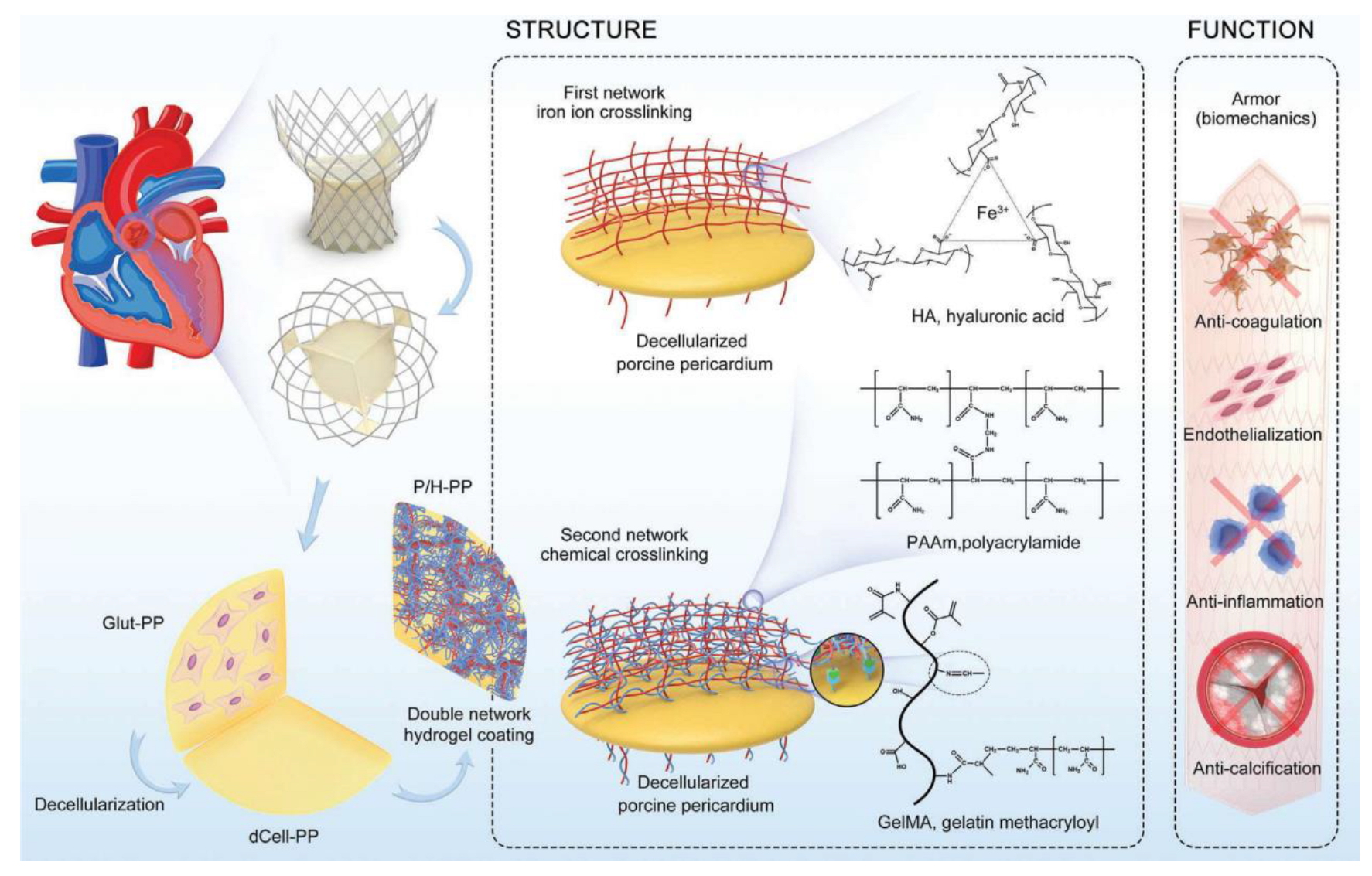

- Cheng, S.; Liu, X.; Qian, Y.; Maitusong, M.; Yu, K.; Cao, N.; Fang, J.; Liu, F.; Chen, J.; Xu, D.; et al. Double-Network Hydrogel Armored Decellularized Porcine Pericardium as Durable Bioprosthetic Heart Valves. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2021, 11, 2102059.

- Dai, J.; Qiao, W.; Shi, J.; Liu, C.; Hu, X.; Dong, N. Modifying decellularized aortic valve scaffolds with stromal cell-derived factor-1α loaded proteolytically degradable hydrogel for recellularization and remodeling. Acta Biomater. 2019, 88, 280–292.

- Guo, R.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, C.; Lu, C.; Yang, G.; Nie, J.; Wang, F.; Dong, N.-G.; Shi, J. Anticalcification Potential of POSS-PEG Hybrid Hydrogel as a Scaffold Material for the Devel-opment of Synthetic Heart Valve Leaflets. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021, 4, 2534–2543.

- Lopez-Moya, M.; Melgar-Lesmes, P.; Kolandaivelu, K.; de la Torre Hernández, J.M.; Edelman, E.R.; Balcells, M. Optimizing Glutaralde-hyde-Fixed Tissue Heart Valves with Chondroitin Sulfate Hydrogel for Endothelialization and Shielding against Deterioration. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 1234–1244.

- Paris, J.L.; Vallet-Regí, M. Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles for Co-Delivery of Drugs and Nucleic Acids in Oncology: A Review. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 526.

- Morrison, C. Alnylam prepares to land first RNAi drug approval. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 156–157.

- Mayer, L.D.; Tardi, P.; Louie, A.C. CPX-351: A nanoscale liposomal co-formulation of daunorubicin and cytarabine with unique biodistribution and tumor cell uptake properties. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 3819–3830.

- Lu, X.Y.; Wu, D.C.; Li, Z.J.; Chen, G.Q. Polymer nanoparticles. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2011, 104, 299–323.

- Zhou, Y.; Quan, G.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Niu, B.; Wu, B.; Huang, Y.; Pan, X.; Wu, C. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles for drug and gene delivery. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2018, 8, 165–177.

- Vallet-Regí, M.; Colilla, M.; Izquierdo-Barba, I.; Manzano, M. Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery: Current Insights. Molecules 2018, 23, 47.

- Arisawa, M. Development of Metal Nanoparticle Catalysis toward Drug Discovery. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2019, 67, 733–771.

- Deng, C.; Dong, N.; Shi, J.; Chen, S.; Xu, L.; Shi, F.; Hu, X.; Zhang, X. Application of decellularized scaffold combined with loaded nanoparticles for heart valve tissue engineering in vitro. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 31, 88–93.

- Zhou, J.; Ding, J.; Zhu, Z.; Xu, J.; Yi, Y.; Li, Y.; Fan, H.; Bai, S.; Yang, J.; Tang, Y.; et al. Surface biofunctionalization of the decellularized porcine aortic valve with VEGF-loaded nano-particles for accelerating endothelialization. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 97, 632–643.

- Hu, C.; Luo, R.; Wang, Y. Heart Valves Cross-Linked with Erythrocyte Membrane Drug-Loaded Nanoparticles as a Biomimetic Strategy for Anti-coagulation, Anti-inflammation, Anti-calcification, and Endothelialization. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 41113–41126.

- Manzano, M.; Colilla, M.; Vallet-Regí, M. Drug delivery from ordered mesoporous matrices. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2009, 6, 1383–1400.

- Manzano, M.; Vallet-Regí, M. New developments in ordered mesoporous materials for drug delivery. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 20, 5593–5604.

- Pinese, C.; Lin, J.; Milbreta, U.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Leong, K.W.; Chew, S.Y. Sustained delivery of siRNA/mesoporous silica nanoparticle complexes from nanofiber scaf-folds for long-term gene silencing. Acta Biomater. 2018, 76, 164–177.

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, J.-L.; Liu, J.-C.; Xu, J.-J.; Tang, Y.-H.; Yi, Y.-P.; Xu, W.-C.; Yu, W.-P.; Lu, C.; et al. Biofunctionalization of decellularized porcine aortic valve with OPG-loaded PCL nanoparticles for anti-calcification. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 11882–11893.

- Wang, Y.; Ma, B.; Liu, K.; Luo, R.; Wang, Y. A multi-in-one strategy with glucose-triggered long-term antithrombogenicity and sequentially enhanced endothelialization for biological valve leaflets. Biomaterials 2021, 275, 120981.

- Ghanbari, H.; Radenkovic, D.; Marashi, S.M.; Parsno, S.; Roohpour, N.; Burriesci, G.; Seifalian, A. Novel heart valve prosthesis with self-endothelialization potential made of modified polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane-nanocomposite material. Biointerphases 2016, 11, 029801.

- Kidane, A.G.; Burriesci, G.; Edirisinghe, M.; Ghanbari, H.; Bonhoeffer, P.; Seifalian, A.M. A novel nanocomposite polymer for devel-opment of synthetic heart valve leaflets. Acta Biomater. 2009, 5, 2409–2417.

- Ghanbari, H.; Kidane, A.G.; Burriesci, G.; Ramesh, B.; Darbyshire, A.; Seifalian, A. The anti-calcification potential of a silsesquioxane nanocomposite polymer under in vitro conditions: Potential material for synthetic leaflet heart valve. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 4249–4260.