Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nur Wahida Abdul Hamid | -- | 1921 | 2022-09-02 06:05:30 | | | |

| 2 | Sirius Huang | Meta information modification | 1921 | 2022-09-02 10:44:12 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Hamid, N.W.A.; Nadarajah, K. Communication Mode between Microorganisms. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/26817 (accessed on 12 January 2026).

Hamid NWA, Nadarajah K. Communication Mode between Microorganisms. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/26817. Accessed January 12, 2026.

Hamid, Nur Wahida Abdul, Kalaivani Nadarajah. "Communication Mode between Microorganisms" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/26817 (accessed January 12, 2026).

Hamid, N.W.A., & Nadarajah, K. (2022, September 02). Communication Mode between Microorganisms. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/26817

Hamid, Nur Wahida Abdul and Kalaivani Nadarajah. "Communication Mode between Microorganisms." Encyclopedia. Web. 02 September, 2022.

Copy Citation

Various processes such as rhizospheric competence, antibiosis, release of enzymes, and induction of systemic resistance in host plants are all used by microbes to influence plant-microbe interactions. These processes are largely founded on chemical signalling. Producing, releasing, detecting, and responding to chemicals are all part of chemical signalling. Different microbes released distinct sorts of chemical signal molecules which interacts with the environment and hosts.

quorum sensing

quorum quenching

autoinducers

1. Introduction

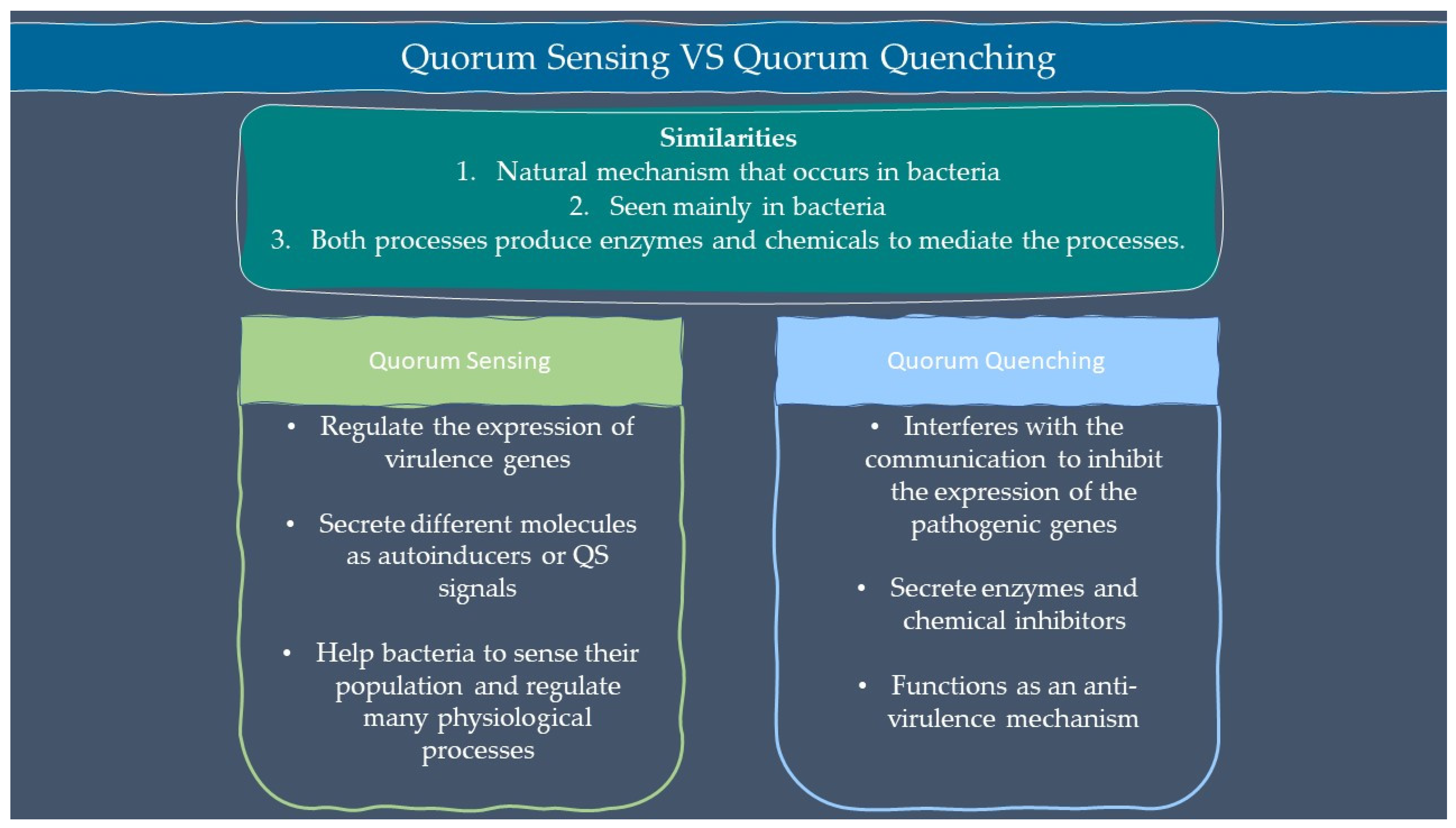

Microbes are sensitive to the changes in their environment. In order to survive harsh environments, microbes alter their gene expression that affects microbial behavior. Microbes need to defend and protect themselves not only against the environment but also against other microbes that exist in the same niche. Communication is an important tool for all organisms to interact with each other. Microorganisms such as bacteria and fungi have a special way of interacting through chemical signal molecules known as autoinducers. These autoinducers trigger chemical communication between microbes. This communication process is called quorum sensing (QS), which allows bacteria and fungi to keep an eye on their surroundings for other bacteria/fungi and adjust their activity on a community scale in response to changes in quantity and species existing within a community. QS is important in microbes as it is used in the production of virulence factors, biofilm formation, and swarming motility [1][2]. Autoinducers are classified into three main types which are AI-1 (N-acyl homoserine lactones, AHLs), oligopeptides or autoinducing peptide and AI-2. Other than the above, there are a few more signalling molecules that are unique and do not belong to any classes such as diffusible signal factor (DSF), Pseudomonas quinolone signal (PQS), and diketopiperazine. AI-1 regulates Gram-negative bacteria QS while oligopeptides are discovered in Gram-positive bacteria. AI-2 is an interspecies autoinducer that is present in many species of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria [3]. Quorum quenching (QQ) on the other hand is a process that interferes with quorum sensing. QQ is believed to have been developed as a natural method by QS-emitting species to clear their own QS signals, or competitive interaction with QS-emitters by QQ organisms. Furthermore, many different species employ QS to control the development and functioning of antimicrobials. Antimicrobial compounds are released by microbes to preserve the population stability which can cause injury or kill the target cells. Next, the capability to colonize a community is greatly influenced by the restricted amount of nutrients in the environment. Microorganisms with specialized metal acquisition systems such as siderophore can bind and promote the absorption of important metals from their environment, thus restricting the capacity of rival microbes to acquire necessary nutrients and able to colonize a community. A summary of quorum sensing and quorum quenching signaling is shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Summary of quorum sensing and quorum quenching.

2. Quorum Sensing

Quorum Sensing is a communication systems used by microorganism, which is critical for the establishment of relationship between the microorganisms and their host [4]. QS is a social characteristic communication between bacteria and the environment in which bacteria creates and senses signal molecules to coordinate their behaviour in a population-dependent manner [1][2]. When QS molecules reach a certain level, bacteria adjust their gene expression pattern to cope with high cell density microbial cell surroundings. Unique extracellular signal molecules known as ‘autoinducers’ are associated with QS. N-acyl homoserine lactones (AHLs) are extensively studied autoinducer in Gram-negative bacteria, that possess an invariant lactone ring and acyl tail of varying lengths, saturations and presence of hydroxyl group [5]. These distinctions in its structure confers species uniqueness as well as differences in genetic regulation depending on the AHL receptor which serves as transcriptional regulator for a variety of bacterial community activities, including biofilm formation and pathogenicity [5].

The biofilm matrix is a harmonious community that helps to protect the microorganism from harsh environment and is vital for colonization [1]. Bacteria in biofilms are known to efficiently sustain communities by secreting extracellular chemicals that allow them to communicate with one another without having to come into direct physical contact. The LuxI is an autoinducer synthase enzyme that synthesizes AHLs, where the AHLs produced will interact with receptor proteins (LuxR homologues) in intracellular spaces of Gram-negative bacteria, and the dimers produced governing the phenotypic gene expression of biofilm formation, enzyme synthesis, manufacturing of antibiotics, and virulence factors [6]. Even at very low concentrations of AHLs, plants may detect their presence and respond in a variety of ways including changes in hormone levels involved in self-defence and the release of hormones associated with growth such as auxin, ethylene and jasmonic acid [7].

Oligopeptide autoinducers are used by Gram-positive bacteria as lead molecules. These autoinducing peptides (AIPs) are ribosomally produced and may have post-translational changes that affect the stability and functionality of their side chains [6]. Peptides typically need transporters to reach the extracellular environment, as they are impermeable to the bacterial membrane [8]. Diffusible signal factors (DSFs) are medium-chain unsaturated fatty acids that regulate QS in a variety of organisms, including Burkholderia cenocepacia, Candida albicans, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, and Xylella fastidiosa, implying the involvement of inter-kingdom signalling pathways. Cis-2-dodecenoic acid, cis-11 methyldode-ca-2,5-dienoic acid, cis-11-methyl-2-dodecenoic acid, cis-10-methyl-2-dodecenoic acid, and trans-2-decenoic acid are examples of DSF compounds [5]. The first discovered DSF was cis-11-methyl-2-dodecenoic acid which was discovered in the Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris. It influences the expression of extracellular enzymes such as Egl and protease, virulence factors and xanthan, as well as the regulation of pathogenicity factors (rpf) genes. The crotonase family enzyme rpfF, acts on fatty acyl carrier protein substrates, and the fatty acyl CoA ligase RpfB is required for X. campestris pv. campestris DSF production. A two-component system for DSF detection and signal transduction consists of the sensor RpfC, and the regulator RpfG [9][10]. Recognition of DSF by RpfC is related to phosphorylation of the HD-GYP which acts as the domain regulator and changes the cellular level of the second messenger cyclic di-GMP. Distinct pathways govern different subsets of Rpf-regulated virulence activities. RpfC favourably influences virulence factor production while adversely regulating DSF synthesis [10].

3. Quorum Quenching

Quorum quenching (QQ) is an interference to the QS system which will disrupt the attack of bacterial population. QQ possesses two main mechanisms; (1) QS signal molecule inhibitors (QSIs), and (2) QS signal molecule degradation enzymes. The QSI mechanism stops signal molecules from interacting with receptor proteins, thus interfering with QS, while the other mechanism reduces signal molecules by generating degrading enzymes, resulting in QQ [8]. Extracts of beans, clover, pea, garlic, geranium, grape, lily, lotus, pepper, strawberry, soybean, vanilla, and yam reduce AHL of QS in a variety of bacterial species [6]. Lactonase present in these plant extracts have QQ action. Lactones such as patulin and penicillic acid found in fungi behave as bacterial AHL signal counterparts. Patulin can be found in apples, pears, peaches, apricots, bananas, and pineapple, making these foods promising anti-QS phyto resources [9].

AHLs can be destroyed or changed by lactone hydrolysis, amidohydrolysis and oxidoreduction [11]. The activity of AHL acylase and AHL lactonase enzymes has been documented to cause AHL degradation that may be caused by multiple phylum members including Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Firmicutes [12]. Furthermore, bacterial oxidoreductases, such as those produced by Rhodococcus sp., have the ability to actively alter AHL [6]. Lactonases that catalyse the hydrolysis of the ester bond to open the AHL ring are classified into several classes based on their folds. Phosphotriesterase-like lactonases are a common type of lactonase which requires two metal ions and a TIM barrel fold (triose-phosphate isomerase) for proper functionality. TIM barrel proteins are crucial because it is needed to support wide range of enzymatic activities [13]. AHL lactonases have been shown to successfully hydrolyzes a variety of lactones, including QS AHLs ranging from C4- to C12-homoserine lactone (HSL) [9], with or without C3 alteration.

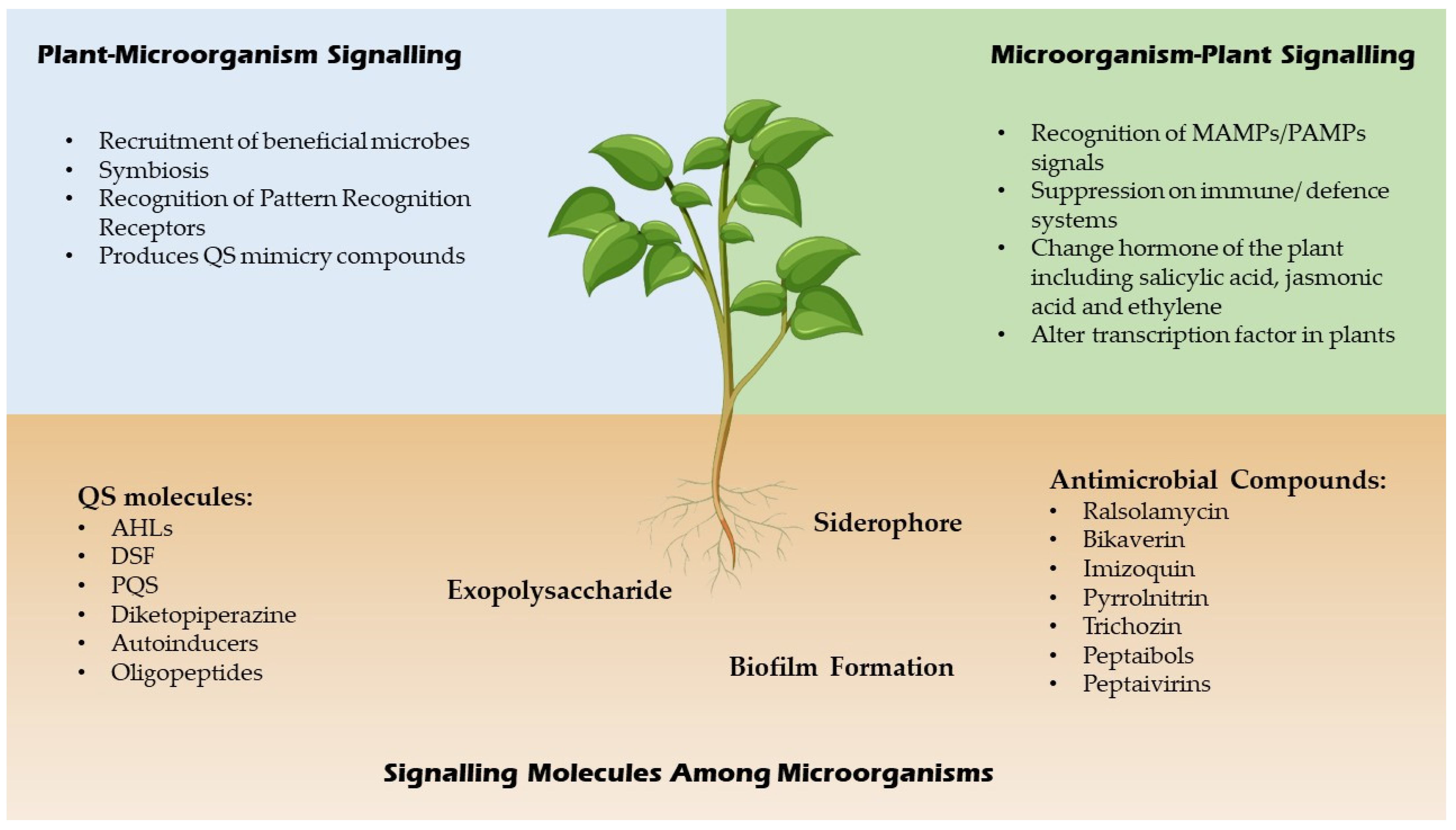

QSI are small molecules which have the capacity to effectively reduce quorum sensing controlled gene expression [14]. These compounds must be stable, specific and resistant to degradation as they will encounter different metabolic reactions in the cell. These compounds alter gene expressions of the targeted genes by binding to different promoters which may interrupt the interaction of the signalling molecules or prevent the synthesis of signal molecules hence inhibit the generation of secondary signals that modulate gene expression [14]. For example, a few Bacillus strains have been associated to aiiiA and TasA genes, which encode for many QSI, including lactonase, and have a broad spectrum antimicrobial action, suggesting that they might be used to manage bacterial diseases biologically [15]. In addition, furanones which are synthesized by fungi have a significant role as QSI for many Gram negative and positive bacteria by triggering the induction of stress response genes in a QS-independent manner [16]. A summary of signalling molecules produced by microbes and plants is shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. Signaling molecules of microbes and plants.

4. Chemical Signalling in Fungi

One of the most prevalent chemical signaling molecule in fungi is farnesol. Following the discovery of farnesol in Candida albicans, it was discovered that lipids (oxylipins), peptides (pheromones), alcohols (tyrosol, farnesol, tryptophol, and 1-phenylethanol), acetaldehydes, and several volatile chemicals are actively engaged in fungal QS systems [14]. QS in fungi is often responsible for germination of spore, production of secondary metabolites, taxonomic transformation and enzyme secretions [17].

Intraspecies of fungi communicate with each other by releasing pheromones. Pheromones are used as signalling molecules to govern spore germination, production of secondary metabolites, structural transformation and enzyme secretion in fungi [17]. Pheromones produced are different based on the alleles expressed at the MAT locus [18]. For instance, Saccharomyces cerevisiae is one of the most popular and broadly described yeast where pheromones generated by this fungus cells are diffusible peptides which are known as a-factor and α-factor. Alleles expressed at the MAT locus will determine the peptide hormone and create only one of the two peptide pheromones. MATα is responsible for α expression where the pheromone precursor is encoded by MFα1 that passes through numerous proteolytic processes before delivering a matured pheromone. MATa meanwhile is responsible for “a” expression, where the a-factor is farnesylated and can be recognized by ABC transporter Ste6p for a-factor secretion [18].

Mycoparasitic fungi such as Trichoderma sp. are commonly used in agriculture to combat other fungal pathogens such as Rhizoctonia solani and Fusarium sp. [19]. Trichoderma sp. produce a few metabolites including harzianopyridone, trichodermin and glivorin which have antifungal or antimicrobial properties that allow them to thrive in various environments [20]. Fusarium produces mycotoxins known as fusaric acid and deoxynivalenol (DON) which can activate defense mechanisms in T. atroviride and Clonostachys rosea which results in mycotoxin detoxification [21][22]. DON and fusaric acid also play an important role as a virulence factor that can cause Fusarium wilt in plant. DON synthesis is related to oxidative stress [23][24] while fusaric acid synthesis is related to metal ion content [25]. This two chemicals can hamper bacteria interaction by QQ of AHL in low concentration, and suppressing phenazine-1-carboxamide production at higher concentrations [26][27]. Other than that, zearalenone (ZEN) is another mycotoxin produced by Fusarium species. C. rosea however was reported to detoxify ZEN by breaking the ring structure of ZEN. Trichoderma sp. turns ZEN into sulphated form and reduces DON into its glycosylated form of deoxynivalenol-3-glucoside [21][28]. Table 1 below shows signal molecules produced by microorganisms and their respective functions.

Table 1. Signal Molecule Produced by Fungi and the Function.

| Organism | Signal Molecule | Role | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fusarium | Fusaric acid |

|

[29][30] |

| S. cerevisiae | Tryptophol |

|

[31] |

| Farnesol |

|

[32] | |

| Debaryomyces nepalensis | Phenylethanol |

|

[33] |

| Penicillium spp. and Aspergillus spp. | Patulin |

|

[34][35] |

| Oxylipins |

|

[36][37] | |

| Penicillium sclerotiorum | Multicolic acid |

|

[17] |

| Fusarium culmorum | Terpenes |

|

[38] |

| Penicillium decumbens | Farnesol |

|

[39] |

| Penicillium expansum | Farnesol |

|

[40] |

| Fusarium graminearum | Farnesol |

|

[40] |

References

- Hartmann, A.; Rothballer, M. Rhizotrophs: Plant Growth Promotion to Bioremediation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 205–217.

- Fatima, K. Insights into Chemical Interaction between Plants and Microbes and its Potential Use in Soil Remediation. Biosci. Rev. 2019, 1, 39–45.

- Guo, M.; Gamby, S.; Zheng, Y.; Sintim, H.O. Small Molecule Inhibitors of AI-2 Signaling in Bacteria: State-of-the-Art and Future Perspectives for Anti-Quorum Sensing Agents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 17694.

- Calatrava-Morales, N.; McIntosh, M.; Soto, M.J. Regulation mediated by N-acyl homoserine lactone quorum sensing signals in the rhizobium-legume symbiosis. Genes 2018, 9, 263.

- Rosier, A.; Bishnoi, U.; Lakshmanan, V.; Sherrier, D.J.; Bais, H.P. A perspective on inter-kingdom signaling in plant–beneficial microbe interactions. Plant Mol. Biol. 2016, 90, 537–548.

- Kim, S.R.; Yeon, K.M. Quorum Sensing as Language of Chemical Signals, 1st ed.; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 81.

- Schenk, S.T.; Schikora, A. AHL-Priming functions via oxylipin and salicylic acid. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 5, 784.

- Saeki, E.K.; Kobayashi, R.K.T.; Nakazato, G. Quorum sensing system: Target to control the spread of bacterial infections. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 142, 104068.

- Achari, G.A.; Ramesh, R. Recent Advances in Quorum Quenching of Plant Pathogenic Bacteria; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019.

- Ryan, R.P.; An, S.; Allan, J.H.; McCarthy, Y.; Dow, J.M. The DSF Family of Cell–Cell Signals: An Expanding Class of Bacterial Virulence Regulators. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1004986.

- Ya’Ar Bar, S.; Dor, S.; Erov, M.; Afriat-Jurnou, L. Identification and Characterization of a New Quorum-Quenching N-acyl Homoserine Lactonase in the Plant Pathogen Erwinia amylovora. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 5652–5662.

- Dessaux, Y.; Grandclément, C.; Faure, D. Engineering the Rhizosphere. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 266–278.

- Halloran, K.T.; Wang, Y.; Arora, K.; Chakravarthy, S.; Irving, T.C.; Bilsel, O.; Brooks, C.L.; Matthews, C.R. Frustration and folding of a TIM barrel protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 16378–16383.

- Padder, S.A.; Prasad, R.; Shah, A.H. Quorum sensing: A less known mode of communication among fungi. Microbiol. Res. 2018, 210, 51–58.

- Yin, X.-T.; Xu, L.-N.; Xu, L.; Fan, S.-S.; Liu, Z.-Y.; Zhang, X.-Y. Evaluation of the efficacy of endophytic Bacillus amyloliquefaciens against Botryosphaeria dothidea and other phytopathogenic microorganisms. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2011, 5, 340–345.

- Landini, P.; Antoniani, D.; Burgess, J.G.; Nijland, R. Molecular mechanisms of compounds affecting bacterial biofilm formation and dispersal. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 86, 813–823.

- Barriuso, J.; Hogan, D.A.; Keshavarz, T.; Martínez, M.J. Role of quorum sensing and chemical communication in fungal biotechnology and pathogenesis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2018, 42, 627–638.

- Cottier, F.; Mühlschlegel, F.A. Communication in Fungi. Int. J. Microbiol. 2012, 2012, 1–9.

- Gorai, P.S.; Barman, S.; Gond, S.K.; Mandal, N.C. Chapter 28—Trichoderma; Amaresan, N., Senthil Kumar, M., Annapurna, K., Kumar, K., Sankaranarayanan, A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 571–591.

- Macías-Rodríguez, L.; Contreras-Cornejo, H.A.; Adame-Garnica, S.G.; del-Val, E.; Larsen, J. The interactions of Trichoderma at multiple trophic levels: Inter-kingdom communication. Microbiol. Res. 2020, 240, 126552.

- Speckbacher, V.; Zeilinger, S. Secondary metabolites of mycoparasitic fungi. In Secondary Metabolites—Sources and Applications; InTech: London, UK, 2018; pp. 37–55.

- Lutz, M.P.; Feichtinger, G.; Défago, G.; Duffy, B. Mycotoxigenic Fusarium and Deoxynivalenol Production Repress Chitinase Gene Expression in the Biocontrol Agent Trichoderma atroviride P1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 3077–3084.

- Montibus, M.; Ducos, C.; Bonnin-Verdal, M.-N.; Bormann, J.; Ponts, N.; Richard-Forget, F.; Barreau, C. The bZIP Transcription Factor Fgap1 Mediates Oxidative Stress Response and Trichothecene Biosynthesis but Not Virulence in Fusarium graminearum. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83377.

- Ponts, N.; Pinson-Gadais, L.; Verdal-Bonnin, M.-N.; Barreau, C.; Richard-Forget, F. Accumulation of deoxynivalenol and its 15-acetylated form is significantly modulated by oxidative stress in liquid cultures of Fusarium graminearum. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2006, 258, 102–107.

- Harborne, J.B. Higher plant–lower plant interactions: Phytoalexins and phytotoxins. In Introduction to Ecological Biochemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1993; pp. 264–297.

- Van Rij, E.T.; Girard, G.; Lugtenberg, B.J.J.; Bloemberg, G.V. Influence of fusaric acid on phenazine-1-carboxamide synthesis and gene expression of Pseudomonas chlororaphis strain PCL1391. Microbiology 2005, 151, 2805–2814.

- Venkatesh, N.; Keller, N.P. Mycotoxins in Conversation with Bacteria and Fungi. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 403.

- Tian, Y.; Tan, Y.; Liu, N.; Yan, Z.; Liao, Y.; Chen, J.; de Saeger, S.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, A. Detoxification of Deoxynivalenol via Glycosylation Represents Novel Insights on Antagonistic Activities of Trichoderma when Confronted with Fusarium graminearum. Toxins 2016, 8, 335.

- López-Díaz, C.; Rahjoo, V.; Sulyok, M.; Ghionna, V.; Martín-Vicente, A.; Capilla, J.; di Pietro, A.; López-Berges, M.S. Fusaric acid contributes to virulence of Fusarium oxysporum on plant and mammalian hosts. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2018, 19, 440–453.

- Ruiz, J.A.; Bernar, E.M.; Jung, K. Production of Siderophores Increases Resistance to Fusaric Acid in Pseudomonas protegens Pf-5. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117040.

- Wongsuk, T.; Pumeesat, P.; Luplertlop, N. Fungal quorum sensing molecules: Role in fungal morphogenesis and pathogenicity. J. Basic Microbiol. 2016, 56, 440–447.

- Guo, H.; Ma, A.; Zhao, G.; Yun, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhuang, G. Effect of Farnesol on Penicillium Decumbens’s Morphology and Cellulase Production. Bioresources 2011, 6, 3252–3259.

- Lei, X.; Deng, B.; Ruan, C.; Deng, L.; Zeng, K. Phenylethanol as a quorum sensing molecule to promote biofilm formation of the antagonistic yeast Debaryomyces nepalensis for the control of black spot rot on jujube. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2022, 185, 111788.

- Jurick, W.M.; Peng, H.; Beard, H.S.; Garrett, W.M.; Lichtner, F.J.; Luciano-Rosario, D.; Macarisin, O.; Liu, Y.; Peter, K.A.; Gaskins, V.L.; et al. Blistering1 modulates penicillium expansum virulence via vesicle-mediated protein secretion. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2020, 19, 344–361.

- Bradshaw, M.J.; Bartholomew, H.P.; Fonseca, J.M.; Gaskins, V.L.; Prusky, D.; Jurick, W.M. Delivering the goods: Fungal secretion modulates virulence during host–pathogen interactions. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2021, 36, 76–86.

- Brodhun, F.; Feussner, I. Oxylipins in fungi. FEBS J. 2011, 278, 1047–1063.

- Yashiroda, Y.; Yoshida, M. Intraspecies cell–cell communication in yeast. FEMS Yeast Res. 2019, 19, 71.

- Schmidt, R.; Etalo, D.W.; de Jager, V.; Gerards, S.; Zweers, H.; de Boer, W.; Garbeva, P. Microbial Small Talk: Volatiles in Fungal-Bacterial Interactions. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 6, 1495.

- Egbe, N.E.; Dornelles, T.O.; Paget, C.M.; Castelli, L.M.; Ashe, M.P. Farnesol inhibits translation to limit growth and filamentation in C. albicans and S. cerevisiae. Microb. Cell 2017, 4, 294.

- Liu, P.; Luo, L.; Guo, J.; Liu, H.; Wang, B.; Deng, B.; Long, C.A.; Cheng, Y. Farnesol induces apoptosis and oxidative stress in the fungal pathogen Penicillium expansum. Mycologia 2010, 102, 311–318.

More

Information

Subjects:

Plant Sciences; Microbiology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.3K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

02 Sep 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No