Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Liqun Liu | -- | 2423 | 2022-07-25 07:23:35 | | | |

| 2 | Liqun Liu | -1385 word(s) | 1038 | 2022-07-25 10:52:36 | | | | |

| 3 | Liqun Liu | + 1394 word(s) | 2432 | 2022-07-25 12:11:47 | | | | |

| 4 | Camila Xu | -62 word(s) | 2346 | 2022-07-27 10:03:35 | | | | |

| 5 | Camila Xu | -2 word(s) | 2344 | 2022-07-27 10:07:48 | | | | |

| 6 | Camila Xu | Meta information modification | 2344 | 2022-07-27 10:12:35 | | | | |

| 7 | Camila Xu | -3 word(s) | 2341 | 2022-07-27 10:19:46 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Han, C.; Liu, L.; Chen, S. Factors Influencing Choices Intention of Online Learning COVID-19. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/25475 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Han C, Liu L, Chen S. Factors Influencing Choices Intention of Online Learning COVID-19. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/25475. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Han, Cunqi, Liqun Liu, Siyu Chen. "Factors Influencing Choices Intention of Online Learning COVID-19" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/25475 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Han, C., Liu, L., & Chen, S. (2022, July 25). Factors Influencing Choices Intention of Online Learning COVID-19. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/25475

Han, Cunqi, et al. "Factors Influencing Choices Intention of Online Learning COVID-19." Encyclopedia. Web. 25 July, 2022.

Copy Citation

Since the COVID-19 outbreak, online learning has become the norm. Primary school students require parental assistance and supervision due to their lack of digital media capabilities and safety concerns. Online learning experiences during the pandemic will affect future parents' choices of online learning, so it is necessary to further clarify the key factors influencing parents' perceptions and attitudes towards online learning during the pandemic. In the post-pandemic era, blended learning, which combines traditional school learning with online learning, is likely to become a common and acceptable way of learning, and parents may face multiple choices of their parents' way of learning.

choice intention

COVID-19

online learning

parents of primary school students

1. Introduction

The outbreak of COVID-19 in late 2019 disrupted regular school education in most schools around the world. In order to ensure the continuous development of education, students at home participate in online learning through network technology (including synchronous or asynchronous and other forms of network learning), which has become one of the most effective emergency measures. However, online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic was significantly different from that before and after the outbreak [1][2]. Students and teachers are not ready for prolonged, subject-wide online learning, but schools must transition from traditional face-to-face learning to technology-driven online learning in the short term. Students, teachers, and parents lack support for technology use, online learning, and training [3], and do not have sufficient knowledge and experience to deal with problems in the process of online learning. Primary school students’ parents are one of the essential participants and policymaker children participate in online learning, especially the lower grade of primary school children. Due to the limited ability of digital media, online contact is not safe and does not exist in learning the appropriate content. Due to the limited ability of digital media, online learning may exist in the process of insecurity, inappropriate content, and too much media use may lead to health problems and risks. As a result, parents face tremendous pressure [4]. Moreover, they need to spend more time and energy supporting, assisting, and supervising the child’s online learning. Studies have shown that the COVID-19 pandemic has a significant negative impact on young children’s learning (children under 11 years of age) [5]. Primary school students lack autonomy in learning and find it difficult to control the learning management system. In the process of online learning, parents are more in need of support and help [6]. As their proxy educators, parents are under tremendous pressure [7].

Parents played an important role in their children’s online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic [8], but parents’ perceptions of their children’s use of online learning to complete schoolwork during the COVID-19 pandemic are mixed. On the one hand, parents approve of online learning, and students have obtained results through online learning. Moreover, the pandemic outbreak led to parents staying at their home office, creating conditions for parents to be involved in their children’s online learning, promoting the parents to participate in the child’s education process to benefit their development [1][9]. On the other hand, online learning during the pandemic also has many problems that parents are worried about, such as eye health problems in children caused by prolonged viewing of electronic screens and financial pressure on families due to the demand for access devices [10].

Online learning experiences during the pandemic will affect future parents’ choices of online learning, so it is necessary to further clarify the key factors influencing parents’ perceptions and attitudes towards online learning during the pandemic. In the post-pandemic era, blended learning, which combines traditional school learning with online learning, is likely to become a common and acceptable way of learning [11], and parents may face multiple choices of their parents’ way of learning.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Online Learning and Parents’ Intention to Choose in the Context of COVID-19

Online learning (e-learning or distance learning) refers to the use of a variety of electronic media and communication technologies such as computers, websites, video conferencing, or virtual classrooms to achieve educational purposes [12][13]. Online learning is a significant way of learning. It can overcome the problem of insufficient teachers and classroom resources, reduce the cost of education, and provide better accessibility. A virtual learning environment may reduce students’ shyness, reduce absenteeism and facilitate students’ active participation in classroom teaching [14]. Surveys have found that distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic was successful in higher education. It does not result in poor academic performance. Students are satisfied with the teacher, the learning process, and the tools [15]. However, existing studies on online learning have focused more on students, teachers, technology, and government policies in the online learning process and paid little attention to parents [16]. While some studies have also noted the importance of parental involvement in student learning during the pandemic, the main focus has been on the motivation and role of parents of special education students and their involvement in student online learning [17][18][19][20]. Existing studies lack systematic research on primary school parents’ perception and evaluation of online learning [21], especially after online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, it is necessary to study further the parents’ cognition, attitude, and choice intention towards online learning.

Previously, a large number of research models and theoretical frameworks has been used to study behavioral intentions such as selection, adoption, and continuous use of online learning. For example, the technology acceptance model (TAM), which is widely used to predict the acceptance of various information technology innovations, is also often used to study students’ intention to use technology and online learning [22]. Students’ perceived ease of use and usefulness of technology are theorized as determinants of their behavioral intentions and actual technology use [23]. Other examples, such as the unified theory of technology acceptance and use (UTAUT), the self-determination theory, and the information system continuity mode are integrated with the TAM and TPB information system achievement model (IS success model) and other common and related research. However, these models and theoretical frameworks mainly focus on the factors that influence the adoption and use of online learning systems, ignoring these factors or the relationship between the use of online learning systems and learning results [24]. In addition, these studies are mainly based on the direct users of online learning systems (mostly students) as the main research object, and lack of investigation on the choice intention of parents of primary school students.

The value-based adoption model (VAM) is used to analyze users’ willingness to use technology and services and the influencing factors behind the intention, which affect consumers’ perceived value and acceptance of the technology and services. Adoption intention is, thus, affected [25]. Benefit and loss are two key factors of perceived value, and “gain” is divided into usefulness and enjoyment, and “profit and loss” are divided into technicality and perceived fee [25]. Some studies have confirmed that the VAM model has better explanatory power and more accurate predictive power than TAM and IS in studying consumers’ adoption intention and behavioral intention [24][26].

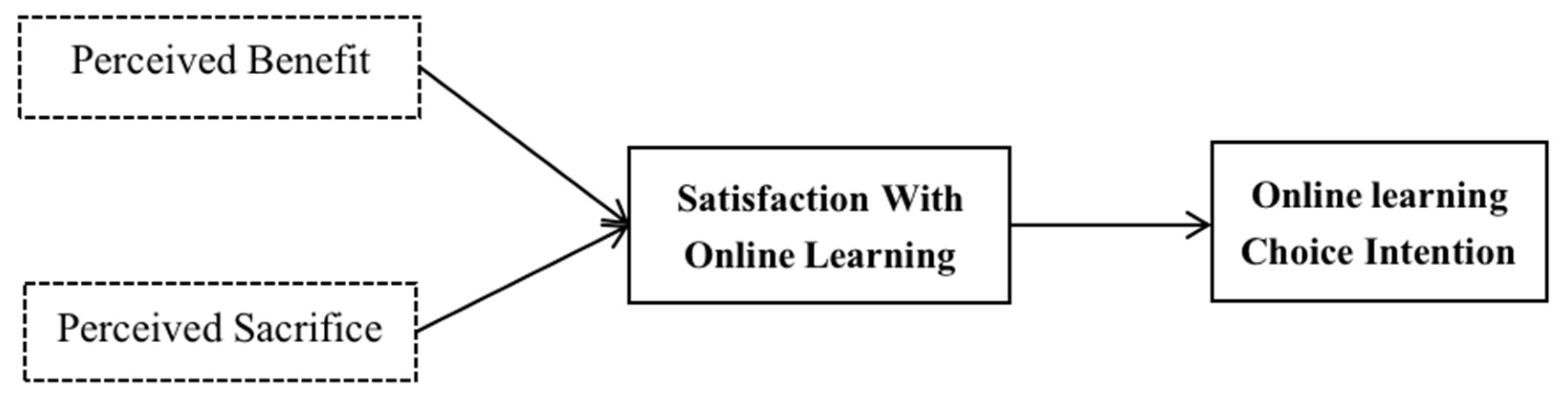

This model has a certain degree of agreement with the study on parents’ intention to choose online learning for primary school students. Parents’ intention to choose online learning means that parents weigh the gains and losses of students’ participation in online learning, comprehensively evaluate the value of online learning, and further decide whether children choose online learning. In this research, the VAM model can be modified and expanded based on the actual technical application scenarios. Firstly, the “adoption intention” in the model is the choice intention of this research. Secondly, “perceived value” is a comprehensive evaluation of parents’ online education experience. In previous literature on online learning and users’ cognition and opinions, “satisfaction” is often used to express and measure learners’ attitudes and opinions towards online learning [12][26][27][28][29]. Therefore, the concept of satisfaction is used to represent “perceived value” in the model. There are many factors that affect learners’ satisfaction [12]. This research divides these factors into two aspects: “perceived benefit” and “perceived sacrifice”, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Analysis framework of primary school parents’ online learning in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 1. Analysis framework of primary school parents’ online learning in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.2.2. Factors Influencing Parents’ Intention to Choose Online Learning

Researchers sorted out the analysis framework of primary school parents’ intention to choose online learning in the pandemic context. The results show that the key to studying the mechanism of their choice of online learning intention is to clarify the perceived gain and loss factors that influence parents’ satisfaction with online learning. The concept of satisfaction comes from the measurement of customer satisfaction by enterprises and is the result of a comparison between expectation and reality [30]. Later, the concept of satisfaction was used in many fields. Parental satisfaction refers to the comparison between the quality of education obtained by parents as guardians of students and the expected quality of education in actual school education [31]. Satisfaction is an important motivation for using an online learning system. In addition, parents are usually not the primary administrators of their children’s formal education, but parents’ satisfaction is of great concern to school administrators and teachers [21]. Analysis of both the studies found that the factors affect online learning satisfaction very much, including the perception of online learning system performance evaluation (usefulness), ease of use, online learning cost, and risk factors, such as logic. These factors can be divided into performance evaluation, perceived ease of use, perceived cost, and perceived risk of four classes.

2.2.1. Performance Evaluation

The technical usefulness of perceived online learning systems has a significant impact on parents’ satisfaction [32][33]. The usefulness of parents’ perception of technology is judged directly by students’ academic performance. Therefore, parents’ perception of students’ academic performance is positively correlated with parents’ satisfaction [31]. Online learning during the pandemic is mainly for students not to miss classes, so the performance evaluation of students’ academic performance is one of the important factors affecting parents’ satisfaction with students’ online learning.

Successful online learning requires students to possess self-management skills, including the abilities and characteristics of planning, time management, and appropriate emotional management. Students’ self-management ability has a positive impact on online learning intentions [34]. Students’ self-management ability is a common concern for parents, especially young pupils who are learning online during the COVID-19 pandemic. Parents are concerned that students cannot maintain self-discipline during the online learning process and that students will have difficulty concentrating and learning efficiently due to long online classes [21][35]. Therefore, the evaluation of students’ self-discipline is related to their learning performance.

Students’ academic performance is also related to the online learning environment. Studies have shown that environmental adaptation of online learning is a key determinant of users’ self-efficacy, and a good environmental adaptation experience will increase users’ motivation to use [36][37]. The online learning environment includes both explicit physical environment factors (such as a computer and network infrastructure, network learning platforms, resources, and equipment tools, etc.) and implicit psychological environment factors (such as interpersonal relationships, cultural atmosphere, etc.), as well as the corresponding learning support and service system. The suitability of the online learning environment for learners during the pandemic affects learners’ learning performance.

In addition, teachers’ support for online learning affects students’ performance [38][39][40]. Teachers, as the main guiders and participants in students’ learning process, play an important role in both an online learning mode and in traditional classroom learning. Parents expect more support and communication from schools or teachers to ensure that their children can learn normally at home. When they do not receive the expected support, parents’ satisfaction decreases [9].

2.2.2. Perceived Ease of Use

Ease of use of technology is also an important factor influencing online satisfaction [27][41]. The technical problems in online learning make parents less confident in supporting their children [42]. Some studies show that parents have low media technology ability or heavy tasks dealing with students’ online learning technical problems. As a result, parents are less satisfied with students’ online learning process during the pandemic [43].

2.2.3. Health Risks

The impact of the use of digital devices on children’s health has always been a research area for scholars, and it is also the focus of parents’ attention to online learning. Parents worry that their children’s long-term exposure to computers, mobile phones, or TV will lead to poor eyesight [44], and that their children’s lack of human interaction will lead to increased loneliness due to long hours of online study. It may exacerbate mental health problems in children [43][45].

2.2.4. Perceived Cost

During the outbreak of online learning, parents worried that households’ equipment (computers, pads, or smartphones, etc.) and learning environment could not meet the needs of online learning. Especially for families with multiple children or parents who need to work at home, not having enough equipment means that people must share or buy a new terminal, and parents and children lack independent work and study space. These situations cause stress and distress to parents [7]. In addition, some studies have concluded that online learning requires parents to pay more time and energy supervising children’s learning and helping with their homework, which brings extra pressure on parents [46]. Therefore, parents’ perceived cost (mainly including money, time, and effort) is a factor affecting satisfaction.

Based on the above analysis, the influencing factors of elementary school students’ parents’ satisfaction can be divided into cognitive gains and perceived benefits of two kinds. For parents of students, learning performance evaluation and perceived ease of use are perceived as benefits. Teachers’ support, parents’ discipline evaluation of students, and the learning environment adaptation degree affect students’ learning results. Therefore, these three factors are a prerequisite for the performance evaluation of factors; perceived cost and perceived risk are a perceived sacrifice, the benefit of a perceived risk is primarily a health risk, and perceived costs include the cost of learning to learn and parents’ time and effort. There could be more factors affecting parents’ satisfaction, especially in the new pandemic under special circumstances, in such a large, and for a long time centralized, discipline of online learning. The factors influencing the evaluation of primary school parents’ satisfaction with online learning have become more complex and diversified. So, it is necessary to explore further the factors influencing parents’ intention to choose online learning during the pandemic and the influencing mechanism of these factors in their intention to choose.

References

- Mishra, N.; Tandon, D.; Tandon, N.; Gupta, I. Online teaching perceptions amidst COVID-19. JIMS8M J. Indian Manag. Strategy 2020, 25, 46–53.

- Liu, X.; Zhou, J.; Chen, L.; Yang, Y.; Tan, J. Impact of COVID-19 epidemic on live online dental continuing education. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2020, 24, 786–789.

- Abu-Rabba, M.Y.; Al-Mughrabib, A.M.; Al-Awidi, H.M. Online learning in the Jordanian kindergartens during COVID-19 pandemic. J. e-Learn. Knowl. Soc. 2021, 17, 59–69.

- Brown, S.M.; Doom, J.R.; Lechuga-Peña, S.; Watamura, S.E.; Koppels, T. Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 110, 104699.

- Spiteri, J.; Deguara, J.; Muscat, T.; Bonello, C.; Farrugia, R.; Milton, J.; Gatt, S.; Said, L. The impact of COVID-19 on children’s learning: A rapid review. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 2022, 39, 1–13.

- Palau, R.; Fuentes, M.; Mogas, J.; Cebrián, G. Analysis of the implementation of teaching and learning processes at Catalan schools during the Covid-19 lockdown. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 2021, 30, 183–199.

- Davis, C.R.; Grooms, J.; Ortega, A.; Rubalcaba, J.A.A.; Vargas, E. Distance learning and parental mental health during COVID-19. Educ. Res. 2021, 50, 61–64.

- Bates, J.; Finlay, J.; O’Connor Bones, U. “Education cannot cease”: The experiences of parents of primary age children (age 4–11) in Northern Ireland during school closures due to COVID-19. Educ. Rev. 2022, 74, 1–23.

- Lau, E.Y.H.; Lee, K. Parents’ views on young children’s distance learning and screen time during COVID-19 class suspension in Hong Kong. Early Educ. Dev. 2021, 32, 863–880.

- Gothwal, V.K.; Kodavati, K.; Subramanian, A. Life in lockdown: Impact of COVID-19 lockdown measures on the lives of visually impaired school-age children and their families in India. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2022, 42, 301–310.

- Devi, B.; Sharma, C. Blended Learning-A Global Solution in the Age of COVID-19. J. Pharm. Res. Int. 2021, 33, 125–136.

- Ozfidan, B.; Fayez, O.; Ismail, H. Student Perspectives of Online Teaching and Learning During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Online Learn. 2021, 25, 461–485.

- Husu, J. Access to equal opportunities: Building of a virtual classroom within two ‘conventional’ schools. J. Educ. Media 2000, 25, 217–228.

- Jacques, S.; Ouahabi, A.; Lequeu, T. Synchronous E-learning in Higher Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Vienna, Austria, 21–23 April 2021; pp. 1102–1109.

- Jacques, S.; Ouahabi, A.; Lequeu, T. Remote Knowledge Acquisition and Assessment During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Eng. Pedagog. 2020, 10, 120–138.

- Yang, C.; Yuan, J. Emergency online education policy and public response during the pandemic of COVID-19 in China. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 2021, 41, 1–16.

- Spear, S.; Parkin, J.; van Steen, T.; Goodall, J. Fostering “parental participation in schooling”: Primary school teachers’ insights from the COVID-19 school closures. Educ. Rev. 2021, 73, 1–20.

- Alabdulaziz, M.S. COVID-19 and the use of digital technology in mathematics education. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 7609–7633.

- Alharthi, M. Parental Involvement in Children’s Online Education During COVID-19; A Phenomenological Study in Saudi Arabia. Early Child. Educ. J. 2022, 50, 1–15.

- Nyanamba, J.M.; Liew, J.; Li, D. Parental burnout and remote learning at home during the COVID-19 pandemic: Parents’ motivations for involvement. Sch. Psychol. 2021, 37, 160–172.

- Hinderliter, H.; Xie, Y.; Ladendorf, K.; Muehsler, H. Path Analysis of Internal and External Factors Associated with Parental Satisfaction over K-12 Online Learning. Comput. Sch. 2022, 38, 354–383.

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.H.; Au, W.; Yates, G. University students’ online learning attitudes and continuous intention to undertake online courses: A self-regulated learning perspective. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2020, 68, 1485–1519.

- Tarhini, A.; Hone, K.; Liu, X. A cross-cultural examination of the impact of social, organisational and individual factors on educational technology acceptance between British and Lebanese university students. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2015, 46, 739–755.

- Islam, A.N. Investigating e-learning system usage outcomes in the university context. Comput. Educ. 2013, 69, 387–399.

- Kim, H.W.; Chan, H.C.; Gupta, S. Value-based adoption of mobile internet: An empirical investigation. Decis. Support Syst. 2007, 43, 111–126.

- Panigrahi, R.; Srivastava, P.R.; Sharma, D. Online learning: Adoption, continuance, and learning outcome—A review of literature. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 43, 1–14.

- Deshwal, P.; Trivedi, A.; Himanshi, H.L.N. Online learning experience scale validation and its impact on learners’ satisfaction. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 112, 2455–2462.

- Liaw, S.S. Investigating students’ perceived satisfaction, behavioral intention, and effectiveness of e-learning: A case study of the Blackboard system. Comput. Educ. 2008, 51, 864–873.

- Zuo, M.; Ma, Y.; Hu, Y.; Luo, H. K-12 students’ online learning experiences during COVID-19: Lessons from China. Front. Educ. China 2021, 16, 1–30.

- Cardozo, R.N. An experimental study of customer effort, expectation, and satisfaction. J. Mark. Res. 1965, 2, 244–249.

- Fantuzzo, J.; Perry, M.A.; Childs, S. Parent satisfaction with educational experiences scale: A multivariate examination of parent satisfaction with early childhood education programs. Early Child. Res. Q. 2006, 21, 142–152.

- Sharma, I.; Kiran, D. Study of parent’s satisfaction for online classes under lockdown due to COVID-19 in India. J. Stat. Manag. Syst. 2021, 24, 17–36.

- Pakaja, F.; Wafa, M. Social family, parental involvement and intentions: Predicting the technology acceptance and interest students learning online. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2021, 29, 1–16.

- Wang, Y.S.; Wu, M.C.; Wang, H.Y. Investigating the determinants and age and gender differences in the acceptance of mobile learning. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2009, 40, 92–118.

- Cui, S.; Zhang, C.; Wang, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Yuan, Q.; Huang, H.; Cheng, F.; Zhang, K.; et al. Experiences and attitudes of elementary school students and their parents toward online learning in China during the COVID-19 pandemic: Questionnaire study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e24496.

- Gui, H.C.; Wong, S.S.L.; Ahmad Zaini, A.; Goh, N.A. Online learning amidst covid-19 pandemic–explicating the nexus between learners’ characteristics, their learning environment and the learning outcomes in built environment studies. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2021, 29, 1–12.

- Kang, Y.J.; Lee, W.J. Self-customization of online service environments by users and its effect on their continuance intention. Serv. Bus. 2015, 9, 321–342.

- Valasidou, A.; Bousiou, D.M. Satisfying distance education students of the Hellenic Open University. E-Mentor 2006, 2, 1–12.

- Schmidt, E.K.; Gallegos, A. Distance learning: Issues and concerns of distance learners. J. Ind. Technol. 2001, 17, 2–5.

- Sahin, I. Predicting student satisfaction in distance education and learning environments. Turk. Online J. Distance Educ. 2007, 8, 113–119.

- Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: System characteristics, user perceptions and behavioral impacts. Int. J. Man-Mach. Stud. 1993, 38, 475–487.

- Anastasiades, P.S.; Vitalaki, E.; Gertzakis, N. Collaborative learning activities at a distance via interactive videoconferencing in elementary schools: Parents’ attitudes. Comput. Educ. 2008, 50, 1527–1539.

- Gritsai, L. Results of Schoolchildren Teaching through Media Technologies in the Context of a Pandemic: Investigation of Parents’Opinions. Media Educ. 2020, 60, 627–635.

- Larreamendy-Joerns, J.; Leinhardt, G. Going the distance with online education. Rev. Educ. Res. 2006, 76, 567–605.

- McMahon, J.; Gallagher, E.A.; Walsh, E.H.; O’Connor, C. Experiences of remote education during COVID-19 and its relationship to the mental health of primary school children. Ir. Educ. Stud. 2021, 40, 457–468.

- Sorensen, C. Learning online at the K-12 level: A parent/guardian perspective. Int. J. Instr. Media 2012, 39, 297–307.

More

Information

Subjects:

Education & Educational Research

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.8K

Entry Collection:

COVID-19

Revisions:

7 times

(View History)

Update Date:

27 Jul 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No