| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Issmat Kassem | -- | 4976 | 2022-06-03 22:27:53 | | | |

| 2 | Dean Liu | -2383 word(s) | 2593 | 2022-06-06 03:56:04 | | |

Video Upload Options

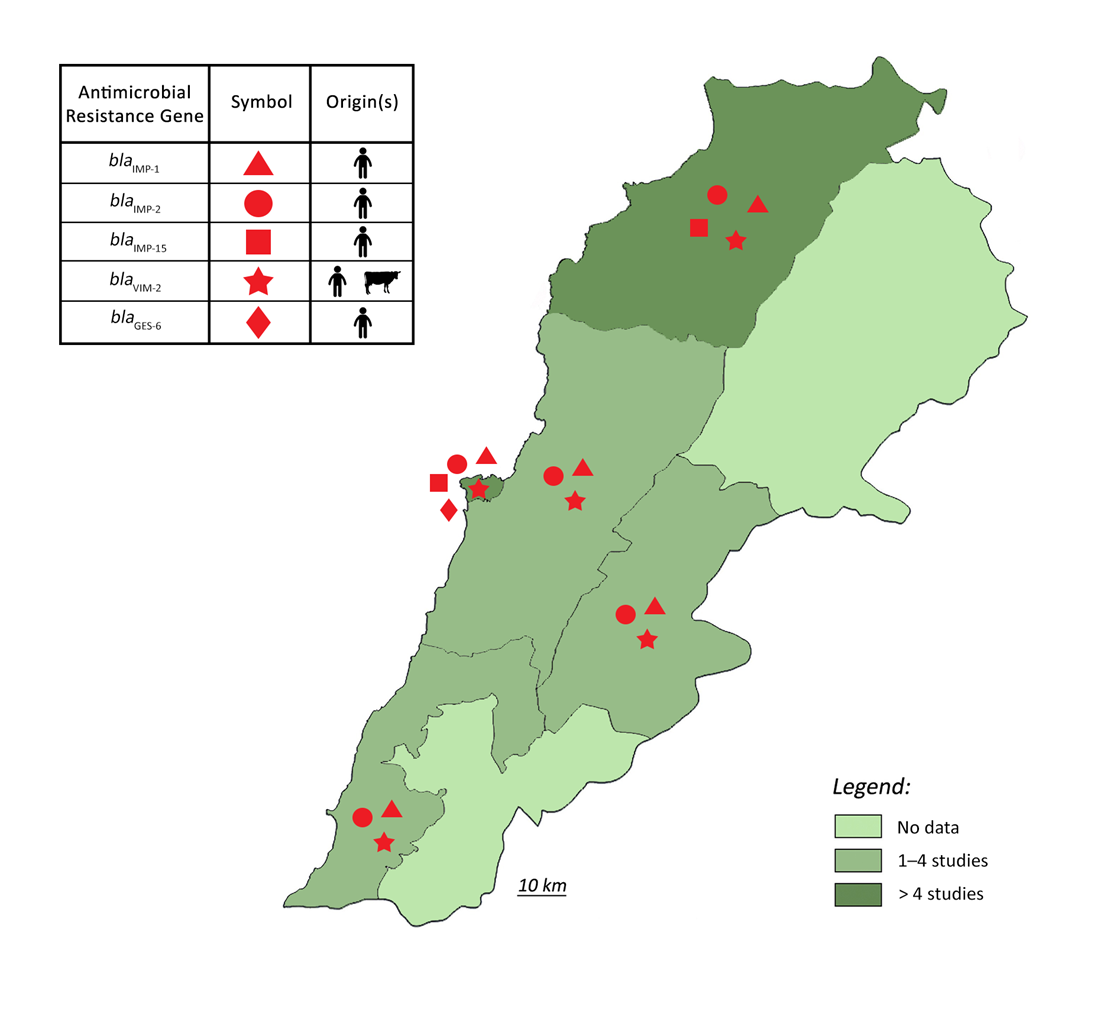

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a common cause of healthcare-associated infections and chronic airway diseases in non-clinical settings. P. aeruginosa is intrinsically resistant to a variety of antimicrobials and has the ability to acquire resistance to others, causing increasingly recalcitrant infections and elevating public health concerns. It is showed that the bacterium was predominant in lesions of patients on mechanical ventilation and in burn patients and those with diabetic foot infections and hematological malignancies. It is also found that carbapenem resistance in P. aeruginosa isolates in Lebanon involved both enzymatic and non-enzymatic mechanisms but depended predominantly on VIM-2 production (40.7%). Additionally, MDR P. aeruginosa was detected in animals, where a study reported the emergence of carbapenemase-producing P. aeruginosa in livestock in Lebanon.

1. Introduction

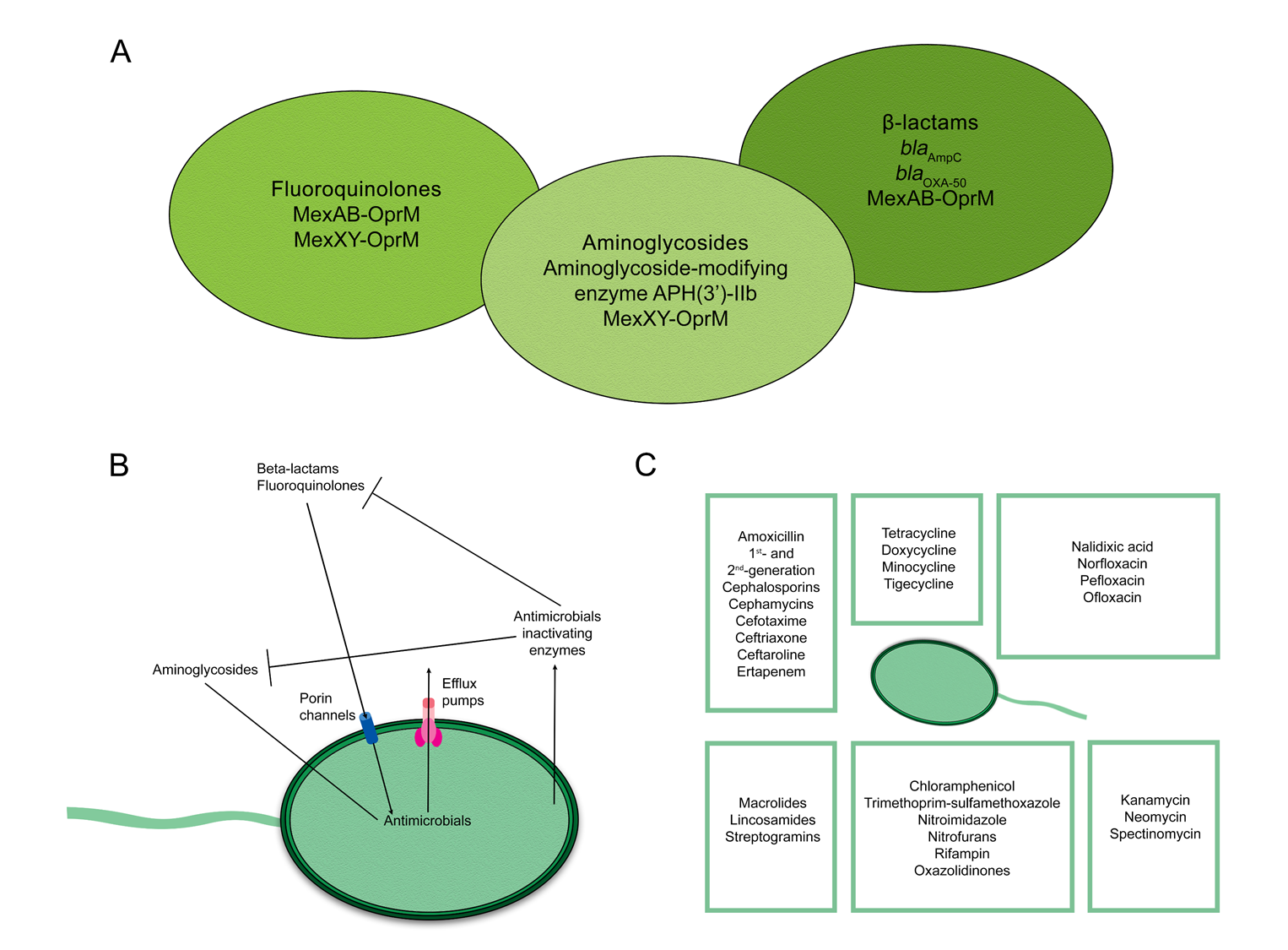

2. Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa

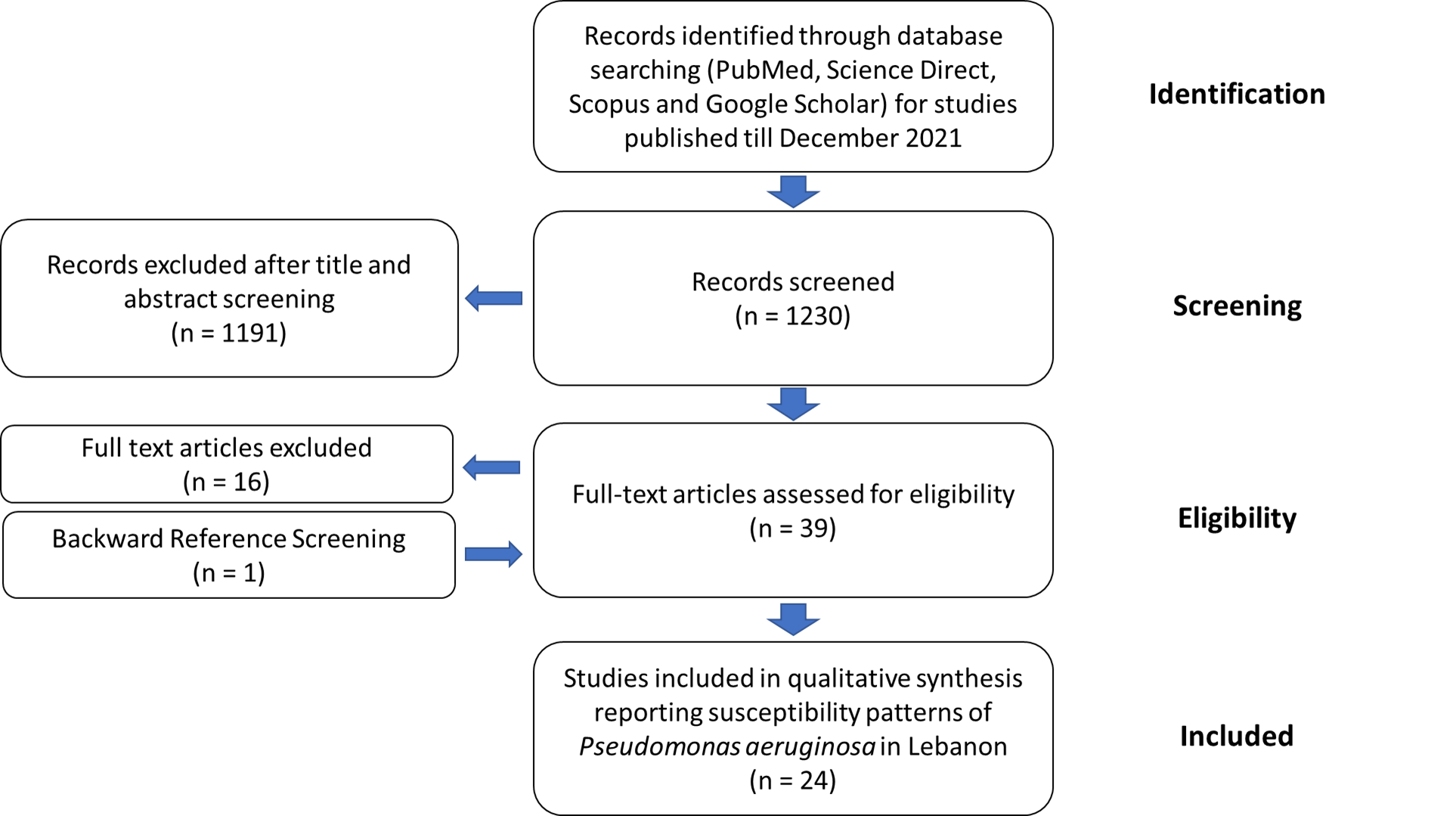

3. Epidemiology of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Resistance in Lebanon

4. Conclusions

References

- Horcajada, J.P.; Montero, M.; Oliver, A.; Sorlí, L.; Luque, S.; Gómez-Zorrilla, S.; Benito, N.; Grau, S. Epidemiology and Treatment of Multidrug-Resistant and Extensively Drug-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 32, e00031-19.

- Filho, F.; Nascimento, A.P.; Costa, M.; Thiago, M.; Menezes, M.; Marisa, N.; Trindade dos Santos, M.; Carvalho-Assef, A.P.; da Silva, F. A systematic strategy to find potential therapeutic targets for Pseudomonas aeruginosa using integrated computational models. Front. Mol. Biosc. 2021, 8, 728129.

- Abbara, A.; Rawson, T.M.; Karah, N.; El-Amin, W.; Hatcher, J.; Tajaldin, B.; Dar, O.; Dewachi, O.; Abu Sitta, G.; Uhlin, B.E.; et al. Antimicrobial resistance in the context of the Syrian conflict: Drivers before and after the onset of conflict and key recommendations. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 73, 1–6.

- Osman, M.; Halimeh, F.B.; Rafei, R.; Mallat, H.; Tom, J.E.; BouRaad, E.; Diene, S.D.; Jamal, S.; Al Atrouni, A.; Dabboussi, F.; et al. Investigation of an XDR-Acinetobacter baumannii ST2 outbreak in an intensive care unit of a Lebanese tertiary care hospital. Future Microbiol. 2020, 15, 1535–1542.

- Hmede, Z.; Kassem, I.I. The Colistin Resistance Gene mcr-1 Is Prevalent in Commensal Escherichia coli Isolated from Preharvest Poultry in Lebanon. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e01304-18.

- Hmede, Z.; Sulaiman, A.A.A.; Jaafar, H.; Kassem, I.I. Emergence of plasmid-borne colistin resistance gene mcr-1 in multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli isolated from irrigation water in Lebanon. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2019, 54, 102–104.

- Al-Omari, S.; Al Mir, H.; Wrayde, S.; Merhabi, S.; Dhaybi, I.; Jamal, S.; Chahine, M.; Bayaa, R.; Tourba, F.; Tantawi, H.; et al. First Lebanese Antibiotic Awareness Week campaign: Knowledge, attitudes and practices towards antibiotics. J. Hosp. Infect. 2019, 101, 475–479.

- Samer, S.; Ghaddar, A.; Hamam, B.; Sheet, I. Antibiotic use and resistance: An unprecedented assessment of university students’ knowledge, attitude and practices (KAP) in Lebanon. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 535.

- Osman, M.; Kasir, D.; Kassem, I.I.; Hamze, M. Shortage of appropriate diagnostics for antimicrobial resistance in Lebanese clinical settings: A crisis amplified by COVID-19 and economic collapse. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2021, 27, 72–74.

- ESCWA. Escwa Warns: More Than Half of Lebanon’s Population Trapped in Poverty 2020. Available online: https://www.unescwa.org/news/lebanon-population-trapped-poverty (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Kassem, I.I.; Osman, M. A brewing storm: The impact of economic collapse on the access to antimicrobials in Lebanon. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2022; ahead of print.

- Dadouch, S.; Durgham, N. Lebanon was Famed for Its Medical Care. Now, Doctors and Nurses are Fleeing in Droves. The Washington Post 2021. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/lebanon-crisis-healthcare-doctors-nurses/2021/11/12/6bf79674-3e33-11ec-bd6f-da376f47304e_story.html (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Dagher, L.A.; Hassan, J.; Kharroubi, S.; Jaafar, H.; Kassem, I.I. Nationwide Assessment of Water Quality in Rivers across Lebanon by Quantifying Fecal Indicators Densities and Profiling Antibiotic Resistance of Escherichia coli. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 883.

- Hassan, J.; Zein Eddine, R.; Mann, D.; Li, S.; Deng, X.; Saoud, I.P.; Kassem, I.I. The mobile colistin resistance gene, mcr-1.1, is carried on Incx4 plasmids in multidrug resistant E. coli isolated from rainbow trout aquaculture. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1636.

- Sourenian, T.; Mann, D.; Li, S.; Deng, X.; Jaafar, H.; Kassem, I.I. Dissemination of multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli harboring the mobile colistin resistance gene mcr-1.1 on transmissible plasmids in the Mediterranean Sea. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020, 22, 84–86.

- Al-Mir, H.; Osman, M.; Drapeau, A.; Hamze, M.; Madec, J.-Y.; Haenni, M. Spread of ESC-, carbapenem- and colistin-resistant Escherichia coli clones and plasmids within and between food workers in Lebanon. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 3135–3143.

- Al-Mir, H.; Osman, M.; Drapeau, A.; Hamze, M.; Madec, J.-Y.; Haenni, M. WGS Analysis of Clonal and Plasmidic Epidemiology of Colistin-Resistance Mediated by mcr Genes in the Poultry Sector in Lebanon. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 624194.

- Osman, M.; Al Mir, H.; Rafei, R.; Dabboussi, F.; Madec, J.-Y.; Haenni, M.; Hamze, M. Epidemiology of antimicrobial resistance in Lebanese extra-hospital settings: An overview. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2019, 17, 123–129.

- Kassem, I.I.; Hijazi, M.A.; Saab, R. On a collision course: The availability and use of colistin-containing drugs in human therapeutics and food-animal farming in Lebanon. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2019, 16, 162–164.

- Kassem, I.I.; Nasser, N.A.; Salibi, J. Prevalence and Loads of Fecal Pollution Indicators and the Antibiotic Resistance Phenotypes of Escherichia coli in Raw Minced Beef in Lebanon. Foods 2020, 9, 1543.

- Blair, J.M.A.; Webber, M.A.; Baylay, A.J.; Ogbolu, D.O.; Piddock, L.J.V. Molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 42–51.

- Pang, Z.; Raudonis, R.; Glick, B.R.; Lin, T.-J.; Cheng, Z. Antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Mechanisms and alternative therapeutic strategies. Biotechnol. Adv. 2019, 37, 177–192.

- Hirsch, E.B.; Brigman, H.V.; Zucchi, P.C.; Chen, A.; Anderson, J.C.; Eliopoulos, G.M.; Cheung, N.; Gilbertsen, A.; Hunter, R.C.; Emery, C.L.; et al. Ceftolozane-tazobactam and ceftazidime-avibactam activity against b-lactam-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and extended-spectrum b-lactamase-producing enterobacterales clinical isolates from U.S. medical centres. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020, 22, 689–694.

- Cultrera, R.; Libanore, M.; Barozzi, A.; D’Anchera, E.; Romanini, L.; Fabbian, F.; De Motoli, F.; Quarta, B.; Stefanati, A.; Bolognesi, N.; et al. Ceftolozane/Tazobactam and Ceftazidime/Avibactam for Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Infections in Immunocompetent Patients: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 640.

- Zamudio, R.; Hijazi, K.; Joshi, C.; Aitken, E.; Oggioni, M.R.; Gould, I.M. Phylogenetic analysis of resistance to ceftazidime/avibactam, ceftolozane/tazobactam and carbapenems in piperacillin/tazobactam-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa from cystic fibrosis patients. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2019, 53, 774–780.

- Ramirez, M.S.; Tolmasky, M.E. Aminoglycoside modifying enzymes. Drug Resist. Updat. 2010, 13, 151–171.

- Zhao, L.; Wang, S.; Li, X.; He, X.; Jian, L. Development of in vitro resistance to fluoroquinolones in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2020, 9, 124.

- Walters, M.S.; Grass, J.E.; Bulens, S.N.; Hancock, E.B.; Phipps, E.C.; Muleta, D.; Mounsey, J.; Kainer, M.A.; Concannon, C.; Dumyati, G.; et al. Carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa at US emerging infections program sites, 2015. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 1281–1288.

- Hamel, M.; Rolain, J.-M.; Baron, S. The History of Colistin Resistance Mechanisms in Bacteria: Progress and Challenges. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 442.

- Fernández, L.; Álvarez-Ortega, C.; Wiegand, I.; Olivares, J.; Kocíncová, D.; Lam, J.S.; Martínez, J.L.; Hancock, R.E.W. Characterization of the Polymyxin B Resistome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 110–119.

- Pathak, A.; Singh, S.; Kumar, A.; Prasad, K. Emergence of chromosome borne colistin resistance gene, mcr-1 in clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 101, 22.

- El-Baky, R.M.A.; Masoud, S.M.; Mohamed, D.S.; Waly, N.G.; Shafik, E.A.; Mohareb, D.A.; Elkady, A.; Elbadr, M.M.; Hetta, H.F. Prevalence and Some Possible Mechanisms of Colistin Resistance Among Multidrug-Resistant and Extensively Drug-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 323–332.

- Liu, Y.-Y.; Chandler, C.E.; Leung, L.M.; McElheny, C.L.; Mettus, R.T.; Shanks, R.M.Q.; Liu, J.-H.; Goodlett, D.R.; Ernst, R.K.; Doi, Y. Structural Modification of Lipopolysaccharide Conferred by mcr-1 in Gram-Negative ESKAPE Pathogens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e00580-17.

- Snesrud, E.; Maybank, R.; Kwak, Y.I.; Jones, A.R.; Hinkle, M.K.; McGann, P. Chromosomally Encoded mcr-5 in Colistin-Nonsusceptible Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e00679-18.

- Abbott, I.J.; Van Gorp, E.; Wijma, R.A.; Dekker, J.; Croughs, P.D.; Meletiadis, J.; Mouton, J.W.; Peleg, A.Y. Efficacy of single and multiple oral doses of fosfomycin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa urinary tract infections in a dynamic in vitro bladder infection model. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 1879–1888.

- Ito, R.; Mustapha, M.M.; Tomich, A.D.; Callaghan, J.D.; McElheny, C.L.; Mettus, R.T.; Shanks, R.M.Q.; Sluis-Cremer, N.; Doi, Y. Widespread Fosfomycin Resistance in Gram-Negative Bacteria Attributable to the Chromosomal fosA Gene. MBio 2017, 8, e00749-17.

- Díez-Aguilar, M.; Morosini, M.I.; Tedim, A.P.; Rodríguez, I.; Aktaş, Z.; Cantón, R. Antimicrobial Activity of Fosfomycin-Tobramycin Combination against Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolates Assessed by Time-Kill Assays and Mutant Prevention Concentrations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 6039–6045.

- Al Bayssari, C.; Dabboussi, F.; Hamze, M.; Rolain, J.-M. Emergence of carbapenemase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii in livestock animals in Lebanon. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 950–951.

- Shaar, T.; Al-Hajjar, R. Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of bacteria at the Makassed General Hospital in Lebanon. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2000, 14, 161–164.

- Araj, G.F.; Uwaydah, M.M.; Alami, S.Y. Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of bacterial isolates at the american university medical center in Lebanon. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1994, 20, 151–158.

- Araj, G.F.; Avedissian, A.Z.; Ayyash, N.S.; Bey, H.A.; El Asmar, R.G.; Hammoud, R.Z.; Itani, L.Y.; Malak, M.R.; Sabai, S.A. A reflection on bacterial resistance to antimicrobial agents at a major tertiary care center in Lebanon over a decade. J. Med. Liban. 2012, 60, 125–135.

- Hamouche, E.; Sarkis, D.K. Evolution of susceptibility to antibiotics of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumanii, in a university hospital center of Beirut between 2005 and 2009. Pathol. Biol. 2012, 60, e15–e20.

- Hamze, M.; Dabboussi, F.; Izard, D. A 4-year study of Pseudomonas aeruginosa susceptibility to antibiotics (1998–2001) in northern Lebanon. Med. Mal. Infect. 2004, 34, 321–324.

- Bourgi, J.; Said, J.M.; Yaakoub, C.; Atallah, B.; Al Akkary, N.; Sleiman, Z.; Ghanimé, G. Bacterial infection profile and predictors among patients Aadmitted to a burn care center: A retrospective study. Burns 2020, 46, 1968–1976.

- Hamze, M.; Osman, M.; Mallat, H.; Achkar, M. Prevalence and antibiotic susceptibility of ear pathogens isolated from patients in Tripoli, north of Lebanon. Int. Arab. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2017, 7, 1–10.

- Osman, M.; Mallat, H.; Hamze, M.; Bou Raad, E. Prevalence and antibiotic susceptibility patterns of bacteria causing urinary uract infections in Youssef hospital center: First report from akkar governorate, north Lebanon. Int. Arab. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2017, 7, 2–4.

- Moghnieh, R.; Araj, G.F.; Awad, L.; Daoud, Z.; Mokhbat, J.E.; Jisr, T.; Abdallah, D.; Azar, N.; Irani-Hakimeh, N.; Balkis, M.M.; et al. A compilation of antimicrobial susceptibility data from a network of 13 Lebanese hospitals reflecting the national situation during 2015–2016. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2019, 8, 41.

- Chamoun, K.; Farah, M.; Araj, G.; Daoud, Z.; Moghnieh, R.; Salameh, P.; Saade, D.; Mokhbat, J.; Abboud, E.; Hamze, M.; et al. Surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in Lebanese hospitals: Retrospective nationwide compiled data. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 46, 64–70.

- Halat, D.H.; Moubareck, C.A.; Sarkis, D.K. Heterogeneity of Carbapenem Resistance Mechanisms Among Gram-Negative Pathogens in Lebanon: Results of the First Cross-Sectional Countrywide Study. Microb. Drug Resist. 2017, 23, 733–743.

- Hammoudi, D.; Moubareck, C.A.; Kanso, A.; Nordmann, P.; Sarkis, D.K. Surveillance of carbapenem non-susceptible Gram negative strains and characterization of carbapenemases of classes A, B, and D in a Lebanese hospital. J. Med. Liban. 2015, 63, 66–73.

- Yaghi, J.; Fattouh, N.; Akkawi, C.; El Chamy, L.; Maroun, R.G.; Khalil, G. Unusually High Prevalence of Cosecretion of Ambler Class A and B Carbapenemases and Nonenzymatic Mechanisms in Multidrug-Resistant Clinical Isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Lebanon. Microb. Drug Resist. 2020, 26, 150–159.

- Dagher, T.N.; Al-Bayssari, C.; Diene, S.; Azar, E.; Rolain, J.-M. Emergence of plasmid-encoded VIM-2–producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from clinical samples in Lebanon. New Microbes New Infect. 2019, 29, 100521.

- Al-Bayssari, C.; Dagher, T.N.; El Hamoui, S.; Fenianos, F.; Makdissy, N.; Rolain, J.-M.; Nasreddine, N. Carbapenem and colistin-resistant bacteria in North Lebanon: Coexistence of MCR-1 and NDM-4 genes in Escherichia coli. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2021, 15, 934-342.

- Al Bayssari, C.; Diene, S.M.; Loucif, L.; Gupta, S.K.; Dabboussi, F.; Mallat, H.; Hamze, M.; Rolain, J.-M. Emergence of VIM-2 and IMP-15 Carbapenemases and Inactivation of oprD Gene in Carbapenem-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa Clinical Isolates from Lebanon. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 4966–4970.

- van Duin, D.; Bonomo, R.A. Ceftazidime/avibactam and ceftolozane/tazobactam: Second-generation b-lactam/b-lactamase inhibitor combinations. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 63, 234–241.

- Araj, G.F.; Berjawi, D.M.; Musharrafieh, U.; El Beayni, N.K. Activity of ceftolozane/tazobactam against commonly encountered antimicrobial resistant Gram-negative bacteria in Lebanon. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2020, 14, 559–564.