Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vinicius Pinto Costa Rocha | -- | 1964 | 2022-05-25 16:02:42 | | | |

| 2 | Jessie Wu | + 1414 word(s) | 3378 | 2022-05-26 02:52:04 | | | | |

| 3 | Jessie Wu | Meta information modification | 3378 | 2022-05-26 02:53:38 | | | | |

| 4 | Jessie Wu | Meta information modification | 3378 | 2022-05-27 08:17:30 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Rocha, V.; Quadros, H.; Meira, C.; , .; Saraiva Hodel, K.; Moreira, D.R. Antiparasitic Activity of Betulinic Acid and Its Derivatives. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23370 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Rocha V, Quadros H, Meira C, , Saraiva Hodel K, Moreira DR. Antiparasitic Activity of Betulinic Acid and Its Derivatives. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23370. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Rocha, Vinicius, Helenita Quadros, Cássio Meira, , Katharine Saraiva Hodel, Diogo Rodrigo Moreira. "Antiparasitic Activity of Betulinic Acid and Its Derivatives" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23370 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Rocha, V., Quadros, H., Meira, C., , ., Saraiva Hodel, K., & Moreira, D.R. (2022, May 25). Antiparasitic Activity of Betulinic Acid and Its Derivatives. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23370

Rocha, Vinicius, et al. "Antiparasitic Activity of Betulinic Acid and Its Derivatives." Encyclopedia. Web. 25 May, 2022.

Copy Citation

Betulinic acid (BA) is a triterpene natural product which has shown antiparasitic activity against Leishmania, Trypanosoma cruzi, and Plasmodium.

betulinic acid

leishmaniasis

treatment

1. Anti-Leishmania Activity of Betulinic Acid

The anti-Leishmania activity of BA and derivatives have been determined and Table 1 summarizes the main activity values of BA present in plant extracts, and as a pure compound, as well as its derivatives tested. BA was found to be one of the biomolecules isolated from Pelliciera rhizophorae, which is an endemic plant from mangroves. Among the biomolecules isolated from this plant, BA was assayed against L. donovani axenic amastigotes. However, this compound did not present significant activity either against Leishmania or T. cruzi. Since BA presented an inhibitory concentration of 50% (IC50) equal to 18 μM against P. falciparum, this suggests the absence or a redundant function of a common drug target in trypanosomatid parasites to explain the absence of activity in trypanosomatids (Table 1) [1]. Similar data were reported by Mamdouh and colleagues (2014), showing that BA isolated from Syzygium samarangense did not present activity against L. major [2]. The BA was also isolated from the dichloromethane fraction from Millettia richardiana barks. This fraction was active against Leishmania, presenting an IC50 10-fold higher than the reference drugs (11.8 µg/mL versus 1.4 µg/mL for pentamidine and 1.2 µg/mL for miltefosine), considering it is an extract compared with a purified drug. However, the BA isolated from this fraction showed moderated activity against L. major and an IC50 of 40 μM (Table 1) [2]. These data suggest that BA, found in many plants which are popularly used based on ethnopharmacological knowledge, presents low activity against Leishmania promastigotes and amastigotes. Therefore, different derivative molecules were synthesized with the aim to improve the anti-Leishmania activity.

Table 1. Summarized activity of betulinic acid against Leishmania.

| Activity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BA Source/Lupane Triterpenoids Derivatives | Leishmania Specie | Promastigotes | Amastigotes | Reference |

| Pelliciera rhizophorae | L. donovani | N.A. | N.A. | [1] |

| Syzygium samarangense | L. major | - | IC50 > 100 μM | [2] |

| Millettia richardiana | L. major | - | IC50 of 40 μM | [3] |

| Semisynthetic lupane triterpenoid 3b-Hydroxy-(20R)-lupan-29-oxo-28-yl-1H-imidazole-1- carboxylate |

L. infantum | IC50 of 50.8 μM | - | [4] |

| Betulinic acid derivative 28-(1H-imidazole-1-yl)-3,28-dioxo-lup-1,20(29)-dien-2-yl-1H-imidazole-1-carboxylate |

L. infantum | IC50 of 25.8 μM | - | [4] |

| Dihydrobetulinic acid | L. donovani | IC50 of 2.6 μM | IC50 of 4.1 μM | [5] |

| Betulonic acid | L. donovani | - | IC50 < 50 μM | [6] |

| Betulin 3-caffeate | L. major | IC50 > 100 | - | [7] |

| Betulinic acid | L. major | IC50 of 2.6 μg/mL | - | [7] |

| Betulin aldehyde | L. amazonensis | IC50 > 300 μg/mL | - | [8] |

| Betulinic acid into nanoformulations containing nanochitosan | L. major | IC50 < 20 µg/mL | IC50 < 20 µg/mL | [9][10] |

| Betulinic acid into PLGA nanoparticles | L. donovani | Significantly reduce amastigote number in infected macrophages | [11] | |

| BA5 | L. amazonensis | IC50 of 4.5 ± 1.1 μM | IC50 of 4.1 ± 0.7 μM | [12] |

| L. major | IC50 of 3.0 ± 0.8 μM | |||

| L. braziliensis | IC50 of 0.9 ± 1.1 μM | |||

| L. infantum | IC50 of 0.15 ± 0.05 μM | |||

N.A.: not active.

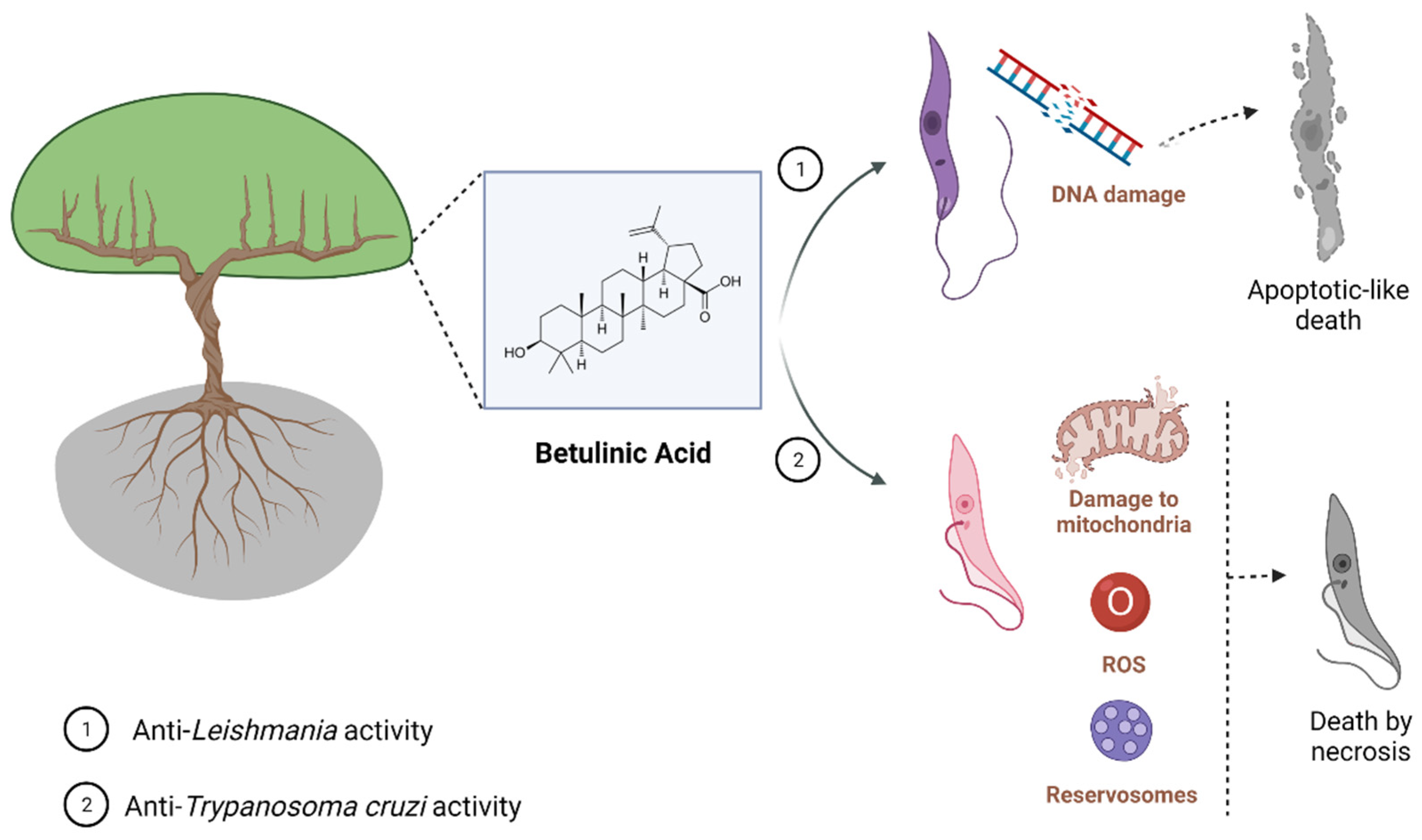

Some BA derivatives produced and tested against Leishmania presented lower IC50 values, suggesting an improvement of its pharmacological effect. The first study of BA derivatives against Leishmania showed that the dihydrobetulinic acid was able to inhibit the interaction between topoisomerases I and II with the parasite DNA, inducing DNA brake and an apoptotic-like death in promastigotes and amastigotes. The IC50 values were significantly lower than that of BA: 2.6 and 4.1 μM for L. donovani promastigotes and amastigotes, respectively [5]. Moreover, dihydrobetulinic acid decreased 92% of the L. donovani infection in golden hamsters when administrated at 10 mg/kg body weight for 6 weeks [5]. On the other hand, other BA derivatives did not present promising results compared to dihydrobetulinic acid, in terms of anti-Leishmania activity and host cell toxicity. This is the case of betulonic acid, betulin 3-caffeate, BA, and betulin aldehyde (Table 1) [6][7][8][9].

The semisynthetic lupane triterpenoids betulin and BA derivatives were developed and assayed against L. infantum promastigotes. Out of sixteen compounds generated, two presented selective cytotoxicity to the parasite, the triterpenoid betulin, and one BA derivative. The compounds 3b-Hydroxy-(20R)-lupan-29-oxo-28-yl-1H-imidazole-1-carboxylate (BT06) and 28-(1H-imidazole-1-yl)-3,28-dioxo-lup-1,20(29)-dien-2-yl-1H-imidazole-1-carboxylate (BT13) showed an IC50 of 50.8 and 25.8 μM, respectively (Table 1). The toxic effect to the parasite was associated with the G0/G1 phase cell cycle arrest, followed by a rounded morphological change, but it was not associated with a significant apoptosis/necrosis induction. This effect seemed to be selective to the parasite, since both drugs did not induce host cell cytotoxicity. Moreover, isobologram analysis showed a synergistic interaction between BT13 with miltefosine, reducing the IC50 from 25.8 to 6 μM [4]. It suggests that BT06 and BT13 may represent a promising structure for the development of potential hits compounds.

Among the heterocyclic betulin derivatives, heterocycloadduct between 3,28-di-O-acetyllupa-12,18-diene and 4-methylurazine presented the highest activity against L. donovani amastigotes. Based on that, 24 derivatives were designed by chemical modifications at positions C-3, C-28, and C-20–C-29 of the lupane skeleton. These derivatives were tested against axenic amastigotes and THP-1-infected human macrophages. The betulonic acid eliminated 98% of axenic amastigotes and 85.3% intracellular parasites at 50 μM (Table 1), and the carbon–carbon double bond seemed to be important for this activity [6]. Modifications in BA backbone can improve the anti-Leishmania activity. In general, these modifications include the C-3 hydroxyl group esterification or oxidation [13].

BA has also been incorporated into nanoformulations containing nanochitosan which showed promising results against Leishmania. BA-containing nanoformulations at a concentration of 20 µg/mL were able to inhibit above 80% the growth of promastigote and amastigote forms of L. major and increased production of nitric oxide (NO), an important metabolite which contributes to anti-Leishmania activity of the host cell, in infected macrophages. A BA-containing nanoformulation was also tested in vivo, and at 20 mg/kg it reduced lesion size in L. major-infected mice (Table 1) [9][10]. A nanoformulation containing BA was also active against L. donovani-infected macrophages, and this activity correlated to the increase of NO e interleukin (IL)-12 and reduction of IL-10 production (Table 1) [11]. These results suggest that a carrier able to increase BA levels at the site of action may improve the activity of this compound in vivo through the direct action of BA against the parasite and, indirectly, by the immunomodulatory activity [14][15]. More studies regarding the use of drug carriers and BA are needed to explore in depth the benefic effects of BA and its derivatives. Moreover, it is well known that cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis are characterized by high inflammatory infiltration, low parasite burden at the lesion site, and tissues necrosis [16][17]. Then, the use of a compound showing dual activity (anti-Leishmania and anti-inflammatory activities) will contribute to the treatment of the clinical manifestations of Leishmaniasis restricted to the skin. Figure 1 shows the main effect found, for now, related to parasite-killing by BA treatment.

Figure 1. Known mechanisms of parasite activity against Leishmania and T. cruzi. Previous work showed that dihydrobetulinic acid inhibits the interaction between topoisomerases I and II with the parasite DNA, inducing DNA brake and an apoptotic-like death in promastigotes and amastigotes. Regarding T. cruzi, it was shown a direct effect of BA5 on plasma membrane integrity, the formation of numerous and atypical vacuoles within the cytoplasm of the parasite, dilatation of some Golgi cisternae, and appearance of profiles of endoplasmatic reticulum involving organelles accompanied by the formation of autophagosomes, which ultimately result in trypomastigote cell death by necrosis. BA5 also reduced M1 markers and upregulated the M2 markers, inducing a regulatory phenotype.

Recently, research group evaluated the leishmanicidal effect of BA5, a BA derivative, previously tested against T. cruzi. The BA5 presented activity against different species of Leishmania promastigotes with an IC50 of 4.5 ± 1.1 μM against L. amazonensis, 3.0 ± 0.8 μM against L. major, 0.9 ± 1.1 μM against L. braziliensis, and 0.15 ± 0.05 μM against L. infantum. This derivative also significantly reduced the percentage and parasitism in infected peritoneal macrophages without host cell toxicity, presenting an IC50 of 4.1 ± 0.7 μM against intracellular parasites. BA5 was able to induce membrane blebbing, flagella damage, and cell shape alterations in treated parasites. Moreover, BA5 acts synergistically to the amphotericin B-killing Leishmania parasite [12].

2. Anti-T. cruzi Activity of Betulinic Acid

The antiparasitic activity of BA has also been validated against Trypanosoma cruzi. Table 2 summarizes the main activity values of BA derived from extracts and as pure compounds. The first evidence that BA has trypanocidal activity was obtained in studies with extracts and fractions containing BA. Campos et al. (2005) evaluated the anti-T. cruzi activity of extracts and fractions from the plant Bertholletia excelsa against trypomastigotes forms (Y strain) [18]. A significant trypanocidal activity of acetone and methanol extract was observed at 500 µg/mL, which promoted a reduction of 100% and 90.3%, respectively, in trypomastigote viability. Furthermore, BA purified from the hexane extract inhibited 75.4% trypomastigotes viability at 500 µg/mL [18]. Extracts and fractions of Ampelozizyphus amazonicus Ducke (Rhamnaceae), a native tree from the Amazon forest, also showed trypanocidal activity against trypomastigotes forms (Y strain) and proved to be a source of bioactive compounds, including BA (Table 2) [19].

Table 2. Summarized activity of betulinic acid against T. cruzi.

| Activity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Strain | Trypomastigotes | Epimastigotes | Amastigotes | Reference |

| Bertholletia excelsa | Y | 100% at 500 µg/mL 1 | - | - | [18] |

| 75.4% at 500 µg/mL 2 | - | - | |||

| BA | Tulahuen | - | IC50 of 50 µg/mL | - | [13] |

| IC50 of 24.16 µg/mL | [20] | ||||

| BA | Tulahuen | IC50 values of 73.43 | [21] | ||

| Semi-synthetic derivative BA5 | Y | IC50 of 1.8 µM | IC50 of 10.6 µM | [22] | |

N.A.: not active. 1 Acetone and methanol extract. 2 Hexane extract.

Most of the subsequent investigations about the trypanocidal effect of BA were carried through in vitro experiments, using Y or Tulahuen T. cruzi strains. Interestingly, BA presented anti-T. cruzi activity against all evolutive forms of T. cruzi. Dominguez-Carmona et al. (2010) showed BA trypanocidal activity against epimastigotes (Tulahuen strain), with an IC50 value of 50 µg/mL [13]. Cretton et al. (2015) demonstrated the activity of BA against T. cruzi amastigote forms (Tulahuen strain), with an IC50 value of 24.16 µg/mL (Table 2) [20]. In addition, Sousa et al. (2017) showed the inhibitory effect of BA on the growth of epimastigotes after 24, 48, and 72 h of incubation with IC50 values of 73.43, 119.8 μM, and 212.2 μM, respectively, in trypomastigotes with IC50 values of 51.88 μM after 24 h of incubation, and in amastigotes with IC50 values of 25.94 μM after 24 or 48 h of incubation (Table 2) [21]. In addition, the mechanism of parasite death was also investigated in epimastigotes forms, indicating that BA promotes alterations in the mitochondrial membrane, increase in reactive oxygen species, and swelling in reservosomes, which leads to parasite cell death by necrosis [21].

Lastly, in order to explore the possibility of improving the trypanocidal activity of BA, semisynthetic derivatives were prepared and evaluated against T. cruzi. Meira et al. (2016) screened a series of amide semisynthetic derivatives of BA and identified the derivative BA5 as a promising trypanocidal agent [22]. BA5 showed a potent anti-T. cruzi activity, with values of IC50 against amastigotes (IC50 = 10.6 µM) and trypomastigotes (IC50 = 1.8 µM) lower than benznidazole (IC50 amastigotes = 13.5 µM; IC50 trypomastigotes = 11.4 µM) (Table 2) [22]. Interestingly, BA5 also demonstrated a potent trypanocidal effect against amastigote forms in an infection model using human cardiomyocytes derived from induced pluripotency stem cells, showing an IC50 value of 3.2 µM, whereas, under the same conditions, benznidazole had an IC50 value of 5.9 µM [23]. Using transmission electron microscopy, it was possible to observe a direct effect of BA5 on plasma membrane integrity, the formation of numerous and atypical vacuoles within the cytoplasm, dilatation of some Golgi cisternae, and appearance of profiles of endoplasmatic reticulum involving organelles accompanied by the formation of autophagosomes, which ultimately result in trypomastigote cell death by necrosis. Most importantly, BA5 combined with benznidazole exhibited synergistic activity against trypomastigotes and amastigotes, which is an interesting finding due to the fact that drug combinations are being largely employed to combat parasitic diseases [4][24][25].

Finally, in a mouse model of chronic Chagas disease, BA5 (at 10 or 1 mg/Kg) decreased inflammation and fibrosis in the hearts of T. cruzi-infected mice. These effects were accompanied by a reduction of proinflammatory cytokines, such as interferon gamma, IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor, and increased IL-10 production. Moreover, BA5 promoted an increase in the expression of macrophage M2 markers, such as arginase 1 and chitanase-3-like protein 1, and a decrease in M1 markers, such as nitric oxide synthase 2, which suggests a polarization to anti-inflammatory/M2 macrophage phenotype in mice treated with BA5 [26].

Altogether, these findings reinforce that BA has trypanocidal activity, and chemical modifications on BA skeleton might enhance trypanocidal activity. However, future investigations in animal models of acute and chronic T. cruzi infection need to be carried out in order to develop BA-based new treatments. Figure 1 shows the main effect found, for now, related to parasite-killing by BA treatment.

3. Anti-Plasmodium Activity of Betulinic Acid

The antiparasitic activity of BA has been also investigated against Plasmodium [27]. Bringmann et al. [28] demonstrated the in vitro antimalarial action of BA isolated, for the first time, from Triphyophyllum peltatum and Ancistrocladus heyneanus, against the P. falciparum asexual blood stages, achieving an IC50 value of 10.46 µg/mL against the chloroquine-sensitive strain NF54. Interestingly, BA isolated from a Tanzanian tree Uapaca nitida Müll-Arg. (Euphorbiaceae) was evaluated for its in vitro activity against T9-69 chloroquine-sensitive and K1 chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum strains. BA was found to have a similar low potency for both strains, with IC50 values of 19.6 µg/mL and 25.9 µg/mL, respectively (Table 3). Moreover, these authors assessed, for the first time, the in vivo activity of BA in a mouse model using P. berghei, but the dosage of 250 mg/kg resulted in animal toxicity and no parasitemia reduction [29]. After these first reports, more studies have been conducted to assess the antimalarial activity of BA and structurally related natural products.

Table 3. Summarized activity of betulinic acid against Plasmodium.

| Source | Strain | Activity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triphyophyllum peltatum | NF54 (chloroquine-sensitive) | IC50 value of 10.46 µg/mL | [28] |

| Ancistrocladus heyneanus | NF54 (chloroquine-sensitive) | IC50 value of 10.46 µg/mL | [28] |

| Uapaca nitida Müll-Arg | T9-69 (chloroquine-sensitive) | IC50 of 19.6 µg/mL | [29] |

| K1 (chloroquine-resistant) | IC50 of 25.9 µg/mL | [29] | |

| Gardenia saxatilis | K1 (chloroquine-resistant) | IC50s of 3.8 µg/mL and 2.9 µg/mL | [30] |

| Diospyros quaesita Thw | D6 (chloroquine-sensitive) | IC50 of 8.1 µM | [31] |

| W2 (chloroquine-resistant) | IC50 of 8.3 µM | [31] | |

| Pure BA | D6 (chloroquine-sensitive) | IC50 of 8.1 µM | [32] |

| W2 (chloroquine-resistant) | IC50 of 8.3 µM | [32] | |

| Psorospermum glaberrimum | W2 (chloroquine-resistant) | IC50 of 5.1 µM | [31] |

| Pentalinon andrieuxii | F32 (chloroquine-sensitive) | IC50 of 22.5 µM | [33] |

| Betulinic acid acetate (BAA) | F32 (chloroquine-sensitive) | IC50 of 11.8 µM | [18] |

| Pure BA | W2 (chloroquine-resistant) | IC50 of 9.89 µM | [34] |

| BAA | W2 (chloroquine-resistant) | IC50 of 5.99 µM | [34] |

| Artesunic acid–betulinic acid hybrid | 3D7 (chloroquine-sensitive) | IC50 of 0.085 µM | [35] |

In a study conducted by Suksamrarn and collaborators [30], 10 triterpenes isolated from Gardenia saxatilis were assessed in vitro against P. falciparum K1, a chloroquine-resistant strain. The results showed that 27-O-p-(Z)- and 27-O-p-(E)-coumarate esters of BA, and a mixture of uncarinic acid E (27-O-p-(E)-coumaroyloxyoleanolic acid) presented a good antiplasmodial activity with IC50 value of 3.8 µg/mL. Additionally, with similar potency, 27-O-p-(Z)- and 27-O-p-(E)-coumarate esters of BA, a mixture of uncarinic acid E (27-O-p-(E)-coumaroyloxyoleanolic acid) and 27-O-p-(E)-coumaroyloxyursolic acid, revealed an IC50 value of 2.9 µg/mL, while BA was not active at the same concentration range (IC50 ≥ 20 µg/mL). Therefore, the addition of a p-coumarate moiety at the 27-position may contribute to increasing the antimalarial properties of BA derivatives (Table 3).

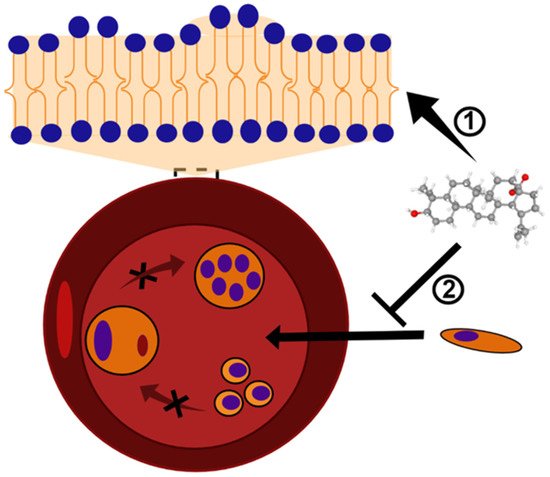

In the study by Ziegler et al. [36], BA and its analogs were evaluated in vitro for their ability to alter the erythrocyte shape and prevent P. falciparum invasion and growth. The BA analogs with a functional chemical group of donating a hydrogen bond caused the formation of echinocyte structures, whereas the analogs lacking this ability induced the formation of stomatocytes. The incorporation of the compounds into the lipid bilayer of erythrocytes may cause a membrane curvature alteration, which apparently presents an inhibitory role for P. falciparum invasion and further development (Figure 2). In agreement, a different study evaluated BA as well as lupeol, another pentacyclic triterpene, and also found that the incorporation of these acids in the host red blood cells consist of a mechanism inhibitory of parasite growth and development by preventing the merozoite internalization [36]. The triterpenoids, including BA, are known to reduce membrane fluidity, and this phenomenon is related to the interaction to the cholesterol-rich membrane rafts. Parasites die into the erythrocyte because its intercellular viability needs the vesicular traffic from the membrane to the vacuole-containing Plasmodium. The erythrocyte membrane modification caused the triterpenoids to affect the traffic of raft-anchored proteins of the erythrocyte host to the internalized Plasmodium vacuoles [37]. This effect of lupane triterpenoids has also been seen in other cell membranes and also mediates other pharmacological effects of BA, such as against malignant cells [38].

Other mechanisms of action for BA and derivatives in Plasmodium infection, such as inhibition of β-hematin formation and modulating calcium pathways in the parasite, have been also investigated [39], but it remains less clear the participation of these mechanisms for the antiparasitic activity of BA.

Other plants have been reported as sources of BA. For instance, Cui-Ying Ma and colleagues [31] produced a chloroform-extract from parts of Diospyros quaesita Thw. (Ebenaceae) and tested for in vitro antimalarial activity on cultures of P. falciparum clones D6 (chloroquine-sensitive) and W2 (chloroquine-resistant). The results showed an antimalarial activity with IC50 values of 8.1 µM and 8.3 µM, respectively (Table 3). In the search for active constituents, the extract went through a series of separations in which seven isolated compounds were generated, including BA. In corroboration with the abovementioned studies [28][29], BA also had a moderated antiplasmodial activity, with an IC50 value of 8.1 µM for D6 and 8.3 µM for W2 (Table 3), being approximately eight-fold lower than betulinic acid 3-caffeate and betulinic acid 3-diacetylcaffeate for both P. falciparum strains; however, differently to these two other compounds, BA did not show cytotoxicity for the cell type tested. Lenta et al. [32] isolated BA from hexane extracts of Psorospermum glaberrimum and evaluated in vitro against P. falciparum W2 strain, showing a moderate activity, with an IC50 of 5.1 µM (Table 3), similar to that reported by Cui-Ying Ma et al. [31].

Chemical modifications to the structure of BA have produced compounds with better antiplasmodial activity. In fact, BA isolated from the crude extract of the leaves of Pentalinon andrieuxii (Apocynaceae) and their semisynthetic betulinic acid acetate (BAA) derivative were evaluated against P. falciparum F32 strain, and both demonstrated antimalarial activity, with IC50 values of 22.5 µM and 11.8 µM, respectively (Table 3). BAA had esterification of the C-3 hydroxyl group, which resulted in an improved activity [13]. In agreement, Cargnin et al. [40] observed that semisynthetic ursolic acid (UA) and BA derivatives modified at C-3 were shown to be more advantageous to antimalarial activity than simultaneous modifications at C-3 and C-28 positions, despite less evidenced, structural modifications at C-27 and C-28 positions also being reported as producing potentiation of the anti-Plasmodium activity [33].

Likewise, Sá and collaborators [41] observed potent in vitro anti-P. falciparum activity of BA and BAA derivative and found similar IC50 values: 9.89 µM and 5.99 µM, respectively (Table 3). However, the lethal dose effective to eliminate the parasite indicated LC50 values four- to six-fold higher than observed for parasite inhibition. Additionally, due to its in vitro activity, BAA was also assessed in vivo, at 10, 50, and 100 mg/kg doses by oral and intraperitoneal routes, in a P. berghei-infection model. The results demonstrated that treatment with BAA by oral route did not alter the levels of parasitemia in mice infected with P. berghei compared to mice treated with saline solution, and, by intraperitoneal route, BAA caused a dose-dependent reduction of parasitemia of at least 70% on the seventh day following infection, when compared to the vehicle-treated group [34].

In the search for effective bioactive hybrid molecules with improved properties compared to their parent compounds, Karagöz et al. [35] developed a series of betulinic acid/betulin-based dimer and hybrid compounds carrying ferrocene and/or artesunic acid moieties by de novo synthesis. These compounds were analyzed in vitro against P. falciparum 3D7 strain and it was found that a series of hybrids/dimers, betulinic acid/betulin, and artesunic acid hybrids showed the most potent antiplasmodial activities. In fact, the results revealed EC50 values of 0.085 µM for artesunic acid–betulinic acid hybrid, 0.0097 µM for artesunic acid, and 1.4 and 3.9 µM for BA and betulin, respectively (Table 3).

The molecular action mechanisms were also investigated in BA and derivatives against P. falciparum strains. Medeiros and collaborators [42] evaluated the in vitro antiplasmodial activity of imidazole derivatives of BA against P. falciparum NF54 and chloroquine-resistant isolated strains and observed that both derivatives presented good IC50s values below 10 µM for both strains. In addition, the BA derivative with ester addition of butyric acid at C-3 also showed maturation inhibition of the parasite’s ring to schizont forms when compared to the start of the treatment, potentiating the antimalarial effect in inhibiting the parasite life cycle. In silico analysis presented a tight bind of BA derivative in the topoisomerase II-DNA complex, which suggests that BA forms a ligand–topoisomerase DNA complex by hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interaction and blocks the cell replication. In addition, both UA and BA derivatives showed synergic effects when combined with artemisinin for both strains, while an additive interaction was observed when combined with chloroquine. Table 3 summarizes the main activity values of BA derived from extracts, and pure BA and its derivative compounds.

Figure 2. BA and analogs may cause deformation in the lipid bilayer and, consequently, alterations in the erythrocyte shape. This mechanism of action results in the formation of echinocytes or stomatocytes structures ➀, and inhibits the Plasmodium invasion and growth ➁. The black X symbol represents a blockage of Plasmodium maturation into erythrocytes. BA structure (CID 64971) was obtained from PubChem [43].

References

- López, D.; Cherigo, L.; Spadafora, C.; Lozamejia, M.A.; Martínez-Luis, S. Phytochemical composition, antiparasitic and α–glucosidase inhibition activities from Pelliciera rhizophorae. Chem. Cent. J. 2015, 9, 53.

- Samy, M.N.; Mamdouh, N.S.; Sugimoto, S.; Matsunami, K.; Otsuka, H.; Kamel, M.S. Taxiphyllin 6′-O-Gallate, Actinidioionoside 6′-O-Gallate and Myricetrin 2″-O-Sulfate from the Leaves of Syzygium Samarangense and Their Biological Activities. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2014, 62, 1013–1018.

- Rajemiarimiraho, M.; Banzouzi, J.-T.; Nicolau-Travers, M.-L.; Ramos, S.; Ali, Z.; Bories, C.; Rakotonandrasana, O.L.; Rakotonandrasana, S.; Andrianary, P.A.; Benoit-Vical, F. Antiprotozoal Activities of Millettia richardiana (Fabaceae) from Madagascar. Molecules 2014, 19, 4200–4211.

- Sousa, M.C.; Varandas, R.; Santos, R.C.; Santos-Rosa, M.; Alves, V.; Salvador, J.A.R. Antileishmanial Activity of Semisynthetic Lupane Triterpenoids Betulin and Betulinic Acid Derivatives: Synergistic Effects with Miltefosine. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89939.

- Chowdhury, A.R.; Mandal, S.; Goswami, A.; Ghosh, M.; Mandal, L.; Chakraborty, D.; Ganguly, A.; Tripathi, G.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; et al. Dihydrobetulinic Acid Induces Apoptosis in Leishmania donovani by Targeting DNA Topoisomerase I and II: Implications in Antileishmanial Therapy. Mol. Med. 2003, 9, 26–36.

- Alakurtti, S.; Bergström, P.; Sacerdoti-Sierra, N.; Jaffe, C.L.; Yli-Kauhaluoma, J. Anti-leishmanial activity of betulin derivatives. J. Antibiot. 2010, 63, 123–126.

- Takahashi, M.; Fuchino, H.; Sekita, S.; Satake, M. In vitro leishmanicidal activity of some scarce natural products. Phytother. Res. 2004, 18, 573–578.

- Gantier, J.-C. Isolation of Leishmanicidal Triterpenes and Lignans from the Amazonian Liana Doliocarpus dentatus (Dilleniaceae). Phytother. Res. 1996, 10, 1–4.

- Zadeh Mehrizi, T.; Shafiee Ardestani, M.; Haji Molla Hoseini, M.; Khamesipour, A.; Mosaffa, N.; Ramezani, A. Novel Nanosized Chitosan-Betulinic Acid Against Resistant Leishmania Major and First Clinical Observation of Such Parasite in Kidney. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11759.

- Mehrizi, T.Z.; Khamesipour, A.; Ardestani, M.S.; Shahmabadi, H.E.; Hoseini, M.H.M.; Mosaffa, N.; Ramezani, A. Comparative analysis between four model nanoformulations of amphotericin B-chitosan, amphotericin B-dendrimer, betulinic acid-chitosan and betulinic acid-dendrimer for treatment of Leishmania major: Real-time PCR assay plus. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 7593–7607.

- Halder, A.; Shukla, D.; Das, S.; Roy, P.; Mukherjee, A.; Saha, B. Lactoferrin-modified Betulinic Acid-loaded PLGA nanoparticles are strong anti-leishmanials. Cytokine 2018, 110, 412–415.

- Magalhães, T.B.D.S.; Silva, D.; keyse, C.; Teixeira, J.D.S.; de Lima, J.D.T.; Barbosa-Filho, J.M.; Moreira, D.R.M.; Guimarães, E.T.; Soares, M.B.P. BA5, a Betulinic Acid Derivative, Induces G0/G1 Cell Arrest, Apoptosis Like-Death, and Morphological Alterations in Leishmania sp. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 5, 732.

- Domínguez-Carmona, D.; Escalante-Erosa, F.; García-Sosa, K.; Ruiz-Pinell, G.; Gutierrez-Yapu, D.; Chan-Bacab, M.; Giménez-Turba, A.; Peña-Rodríguez, L. Antiprotozoal activity of Betulinic acid derivatives. Phytomed. Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2010, 17, 379–382.

- Ríos, J.-L. Effects of triterpenes on the immune system. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 128, 1–14.

- Renda, G.; Gökkaya, I.; Şöhretoğlu, D. Immunomodulatory properties of triterpenes. Phytochem. Rev. 2021, 1–27.

- Volpedo, G.; Pacheco-Fernandez, T.; Holcomb, E.A.; Cipriano, N.; Cox, B.; Satoskar, A.R. Mechanisms of Immunopathogenesis in Cutaneous Leishmaniasis And Post Kala-azar Dermal Leishmaniasis (PKDL). Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 685296.

- Scorza, B.M.; Carvalho, E.M.; Wilson, M.E. Cutaneous Manifestations of Human and Murine Leishmaniasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1296.

- Campos, F.; Januário, A.H.; Rosas, L.V.; Nascimento, S.K.; Pereira, P.S.; Franca, S.; Cordeiro, M.S.; Toldo, M.P.; de Albuquerque, S. Trypanocidal activity of extracts and fractions of Bertholletia excelsa. Fitoterapia 2005, 76, 26–29.

- Rosas, L.; Cordeiro, M.; Campos, F.; Nascimento, S.; Januário, A.; França, S.; Nomizo, A.; Toldo, M.; Albuquerque, S.; Pereira, P. In vitro evaluation of the cytotoxic and trypanocidal activities of Ampelozizyphus amazonicus (Rhamnaceae). Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2007, 40, 663–670.

- Cretton, S.; Bréant, L.; Pourrez, L.; Ambuehl, C.; Perozzo, R.; Marcourt, L.; Kaiser, M.; Cuendet, M.; Christen, P. Chemical constituents from Waltheria indica exert in vitro activity against Trypanosoma brucei and T. cruzi. Fitoterapia 2015, 105, 55–60.

- Sousa, P.L.; Souza, R.O.D.S.; Tessarolo, L.D.; Menezes, R.; Sampaio, T.L.; Canuto, J.A.; Martins, A.M.C. Betulinic acid induces cell death by necrosis in Trypanosoma cruzi. Acta Trop. 2017, 174, 72–75.

- Meira, C.S.; Filho, J.M.B.; Lanfredi-Rangel, A.; Guimarães, E.T.; Moreira, D.R.; Soares, M.B.P. Antiparasitic evaluation of betulinic acid derivatives reveals effective and selective anti-Trypanosoma cruzi inhibitors. Exp. Parasitol. 2016, 166, 108–115.

- Portella, D.C.N.; Rossi, E.A.; Paredes, B.D.; Bastos, T.M.; Meira, C.S.; Nonaka, C.V.K.; Silva, D.N.; Improta-Caria, A.; Moreira, D.R.M.; Leite, A.C.L.; et al. A Novel High-Content Screening-Based Method for Anti-Trypanosoma cruzi Drug Discovery Using Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes. Stem Cells Int. 2021, 2021, 2642807.

- Alirol, E.; Schrumpf, D.; Heradi, J.A.; Riedel, A.; De Patoul, C.; Quere, M.; Chappuis, F. Nifurtimox-Eflornithine Combination Therapy for Second-Stage Gambiense Human African Trypanosomiasis: Médecins Sans Frontières Experience in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2012, 56, 195–203.

- Diniz, L.; Urbina, J.A.; De Andrade, I.M.; Mazzeti, A.L.; Martins, T.A.F.; Caldas, I.; Talvani, A.; Ribeiro, I.; Bahia, M.T. Benznidazole and Posaconazole in Experimental Chagas Disease: Positive Interaction in Concomitant and Sequential Treatments. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2013, 7, e2367.

- Meira, C.S.; Santos, E.D.S.; Espírito-Santo, R.F.D.; Vasconcelos, J.; Orge, I.; Nonaka, C.K.V.; Barreto, B.C.; Caria, A.C.I.; Silva, D.; Filho, J.M.B.; et al. Betulinic Acid Derivative BA5, Attenuates Inflammation and Fibrosis in Experimental Chronic Chagas Disease Cardiomyopathy by Inducing IL-10 and M2 Polarization. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1257.

- Da Silva, G.N.; Maria, N.R.; Schuck, D.C.; Cruz, L.N.; de Moraes, M.S.; Nakabashi, M.; Graebin, C.; Gosmann, G.; Garcia, C.R.; Gnoatto, S.C. Two series of new semisynthetic triterpene derivatives: Differences in anti-malarial activity, cytotoxicity and mechanism of action. Malar. J. 2013, 12, 89.

- Bringmann, G.; Saeb, W.; Assi, L.; François, G.; Narayanan, A.S.S.; Peters, K.; Peters, E.-M. Betulinic Acid: Isolation from Triphyophyllum peltatum and Ancistrocladus heyneanus, Antimalarial Activity, and Crystal Structure of the Benzyl Ester. Planta Med. 1997, 63, 255–257.

- Steele, J.C.P.; Warhurst, D.C.; Kirby, G.C.; Simmonds, M.S.J. In vitro and In vivo evaluation of betulinic acid as an antimalarial. Phytother. Res. 1999, 13, 115–119.

- Suksamrarn, A.; Tanachatchairatana, T.; Kanokmedhakul, S. Antiplasmodial triterpenes from twigs of Gardenia saxatilis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003, 88, 275–277.

- Ma, C.-Y.; Musoke, S.F.; Tan, G.T.; Sydara, K.; Bouamanivong, S.; Southavong, B.; Soejarto, D.D.; Fong, H.H.S.; Zhang, H.-J. Study of Antimalarial Activity of Chemical Constituents fromDiospyros quaesita. Chem. Biodivers. 2008, 5, 2442–2448.

- Ndjakou Lenta, B.; Devkota, K.P.; Ngouela, S.; Fekam Boyom, F.; Naz, Q.; Choudhary, M.I.; Tsamo, E.; Rosenthal, P.J.; Sewald, N. Anti-Plasmodial and Cholinesterase Inhibiting Activities of Some Constituents of Psorospermum Glaberrimum. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2008, 56, 222–226.

- Isah, M.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Mohammed, A.; Aliyu, A.B.; Masola, B.; Coetzer, T. A systematic review of pentacyclic triterpenes and their derivatives as chemotherapeutic agents against tropical parasitic diseases. Parasitology 2016, 143, 1219–1231.

- de Sá, M.S.; Costa, J.F.O.; Krettli, A.U.; Zalis, M.G.; Maia, G.L.D.A.; Sette, I.M.F.; Câmara, C.D.A.; Filho, J.M.B.; Giulietti-Harley, A.M.; Ribeiro Dos Santos, R.; et al. Antimalarial Activity of Betulinic Acid and Derivatives in Vitro against Plasmodium Falciparum and in Vivo in P. Berghei-Infected Mice. Parasitol. Res. 2009, 105, 275–279.

- Karagöz, A.Ç.; Leidenberger, M.; Hahn, F.; Hampel, F.; Friedrich, O.; Marschall, M.; Kappes, B.; Tsogoeva, S.B. Synthesis of New Betulinic Acid/Betulin-Derived Dimers and Hybrids with Potent Antimalarial and Antiviral Activities. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2019, 27, 110–115.

- Ziegler, H.L.; Staalsø, T.; Jaroszewski, J.W. Loading of Erythrocyte Membrane with Pentacyclic Triterpenes Inhibits Plasmodium falciparum Invasion. Planta Med. 2006, 72, 640–642.

- Friedrichson, T.; Kurzchalia, T.V. Microdomains of GPI-anchored proteins in living cells revealed by crosslinking. Nature 1998, 394, 802–805.

- Dubinin, M.V.; Semenova, A.A.; Ilzorkina, A.I.; Mikheeva, I.B.; Yashin, V.A.; Penkov, N.V.; Vydrina, V.A.; Ishmuratov, G.Y.; Sharapov, V.A.; Khoroshavina, E.I.; et al. Effect of betulin and betulonic acid on isolated rat liver mitochondria and liposomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2020, 1862, 183383.

- Silva, G.N.S.; Schuck, D.C.; Cruz, L.N.; Moraes, M.S.; Nakabashi, M.; Gosmann, G.; Garcia, C.R.S.; Gnoatto, S.C.B. Investigation of antimalarial activity, cytotoxicity and action mechanism of piperazine derivatives of betulinic acid. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2014, 20, 29–39.

- Cargnin, S.T.; Staudt, A.F.; Medeiros, P.; de Medeiros Sol Sol, D.; de Azevedo Dos Santos, A.P.; Zanchi, F.B.; Gosmann, G.; Puyet, A.; Garcia Teles, C.B.; Gnoatto, S.B. Semisynthesis, Cytotoxicity, Antimalarial Evaluation and Structure-Activity Relationship of Two Series of Triterpene Derivatives. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 28, 265–272.

- Wicht, K.J.; Mok, S.; Fidock, D.A. Molecular Mechanisms of Drug Resistance in Plasmodium Falciparum Malaria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 74, 431–454.

- Sol Sol de Medeiros, D.; Tasca Cargnin, S.; Azevedo Dos Santos, A.P.; de Souza Rodrigues, M.; Berton Zanchi, F.; Soares de Maria de Medeiros, P.; de Almeida E Silva, A.; Bioni Garcia Teles, C.; Baggio Gnoatto, S.C. Ursolic and Betulinic Semisynthetic Derivatives Show Activity against CQ-Resistant Plasmodium Falciparum Isolated from Amazonia. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2021, 97, 1038–1047.

- Betulinic Acid | C30H48O3—PubChem. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Betulinic-acid#section=2D-Structure (accessed on 27 February 2022).

More

Information

Subjects:

Biology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

855

Revisions:

4 times

(View History)

Update Date:

31 May 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No