Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wen-Chin Lee | -- | 3687 | 2022-04-15 17:33:28 | | | |

| 2 | Vivi Li | -8 word(s) | 3679 | 2022-04-18 04:06:28 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Lee, W.; Tsai, K.; Chen, Y.; , .; Li, L.; Lee, C. SGLT2 Inhibitors. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21825 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Lee W, Tsai K, Chen Y, , Li L, Lee C. SGLT2 Inhibitors. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21825. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Lee, Wen-Chin, Kai-Fan Tsai, Yung-Lung Chen, , Lung-Chih Li, Chien-Te Lee. "SGLT2 Inhibitors" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21825 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Lee, W., Tsai, K., Chen, Y., , ., Li, L., & Lee, C. (2022, April 15). SGLT2 Inhibitors. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21825

Lee, Wen-Chin, et al. "SGLT2 Inhibitors." Encyclopedia. Web. 15 April, 2022.

Copy Citation

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors are a new class of oral glucose-lowering agents. Apart from their glucose-lowering effects, large clinical trials assessing certain SGLT2 inhibitors have revealed cardiac and renal protective effects in non-diabetic patients. These excellent outcomes motivated scientists and clinical professionals to revisit their underlying mechanisms. In addition to the heart and kidney, redox homeostasis is crucial in several human diseases, including liver diseases, neural disorders, and cancers, with accumulating preclinical studies demonstrating the therapeutic benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors.

SGLT2 inhibitors

antioxidants

diabetes

cardiovascular diseases

nephropathy

liver diseases

neural disorders

cancers

1. Introduction

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors are a new class of oral glucose-lowering agents that block renal glucose reabsorption. SGLT2 inhibitors approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and/or similar bureau in the European Union and other countries include empagliflozin, dapagliflozin, canagliflozin, ertugliflozin, ipragliflozin, tofogliflozin, luseogliflozin, and remogliflozin [1]. In addition to lowering blood glucose, SGLT2 inhibitors can reduce body weight, improve visceral adiposity, lower blood pressure, and normalize lipid profile and serum uric acid levels [2][3][4][5]. Notably, recent cardiovascular outcome trials (CVOTs) assessing SGLT2 inhibitors have shown improvements in cardiovascular and renal outcomes in patients with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [6][7][8][9][10][11][12]. Based on accumulating evidence, the American Diabetes Association (ADA)/European Association of the Study for Diabetes (EASD) recommends SGLT2 inhibitors as the mainstay of treatment for T2DM [13].

1.1. Potential Antioxidant Roles of SGLT2 Inhibitors in Cardiorental Benefits in Landmark Clinical Trials

Several mechanisms underlying the renal and cardiovascular benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors have been proposed. SGLT2 inhibitors have been shown to directly reduce high glucose-induced oxidative stress in the proximal tubules [14][15][16]. Other mechanisms include reduced glomerular hyperfiltration via tubuloglomerular feedback, reduced inflammation, ameliorated fibrosis, attenuated sympathetic nervous system activation, and improved mitochondrial function [14][17][18][19]. Interestingly, SGLT2 is not expressed in the adult heart. Proposed mechanisms explaining the cardioprotective effects of SGLT2 inhibitors include osmotic diuresis, natriuresis, improved renal function, blood pressure reduction, improved vascular function, increased hematocrit, changes in tissue sodium handling, reduced adipose tissue-mediated inflammation and proinflammatory cytokine production, a shift toward ketone bodies as the metabolic substrate, lowered serum uric acid levels, suppression of advanced glycation end product (AGE) signaling, and decreased oxidative stress [1][20]. Most of these mechanisms account for the regulatory interplay between the kidney and heart. Notably, SGLT2 inhibitors are capable of reducing oxidative stress in the heart [21] and kidney [14][22]. As potential antioxidants, SGLT2 inhibitors may offer direct cardioprotection and renoprotection.

1.2. SGLT2 Inhibitors Reduce Oxidative Stress in Human Diseases

Oxidative stress, defined as an imbalance between pro-oxidants and antioxidants, is a crucial factor underlying the pathogenesis of multiple human diseases including diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, nephropathies, liver diseases, neural disorders, and cancers [23]. SGLT2 inhibitors act as indirect antioxidants due to their ability to reduce high glucose-induced oxidative stress. In addition, SGLT2 inhibitors have been shown to reduce free radical generation [24], suppress pro-oxidants (e.g., NADPH oxidase 4 [NOX4] and thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances [TBARS]) [25][26], and upregulate antioxidant systems such as superoxide dismutases (SODs) and glutathione (GSH) peroxidases [27][28][29]. SGLT2 inhibitors have been shown to suppress cellular proliferation by reducing oxidative stress in multiple types of cancer [30][31][32][33][34]. Detailed discussion addressing specific markers of pro-oxidants and antioxidants that are examined in various studies is presented in subsequent sections under different disease headings.

1.3. The Anti-Inflammatory Features of SGLT2 Inhibitors

Inflammation plays important roles in diabetes, chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, liver diseases, neural disorders, and cancers. In various experimental disease models, SGLT2 inhibitors have been demonstrated to exert anti-inflammatory effects [35]. They are able to directly downregulate the expression of proinflammatory mediators including monocyte chemoattractant proteinrac (MCP-1), TGF-β, TNF-α, interleukin-6 (IL-6), nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and C-reactive protein (CRP) [26][36][37]. In addition to these direct influences of SGLT2 inhibitors on inflammation, SGLT2 inhibitors are also able to attenuate inflammation by regulating renin-angiotensin system (RAS) activity, tissue hemodynamic alterations and the imbalanced redox state [38][39]. Oxidative stress activates a variety of transcription factors, including hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α, p53, NF-κB, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) γ, and nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 (Nrf2), which, in turn, lead to the expression of various chemokines and inflammatory cytokines [40][41]. By reducing oxidative stress, in various disease models, SGLT2 inhibitors have been shown to attenuate inflammation by regulating transcription factors of these chemokines and cytokines. Detailed pathways will be discussed in subsequent sections in a disease-specific fashion.

1.4. A Unique Perspective of SGLT2 Inhibitors

Oxidative stress plays a crucial role in numerous common but debilitating human diseases. As a result, reducing oxidative stress acts as a promising strategy to offer the unmet needs of existing treatments of these diseases. Accumulating evidence has demonstrated the therapeutic potential of SGLT2 inhibitors in these diseases, but the antioxidant roles of SGLT2 inhibitors in these diseases are yet to be reviewed.

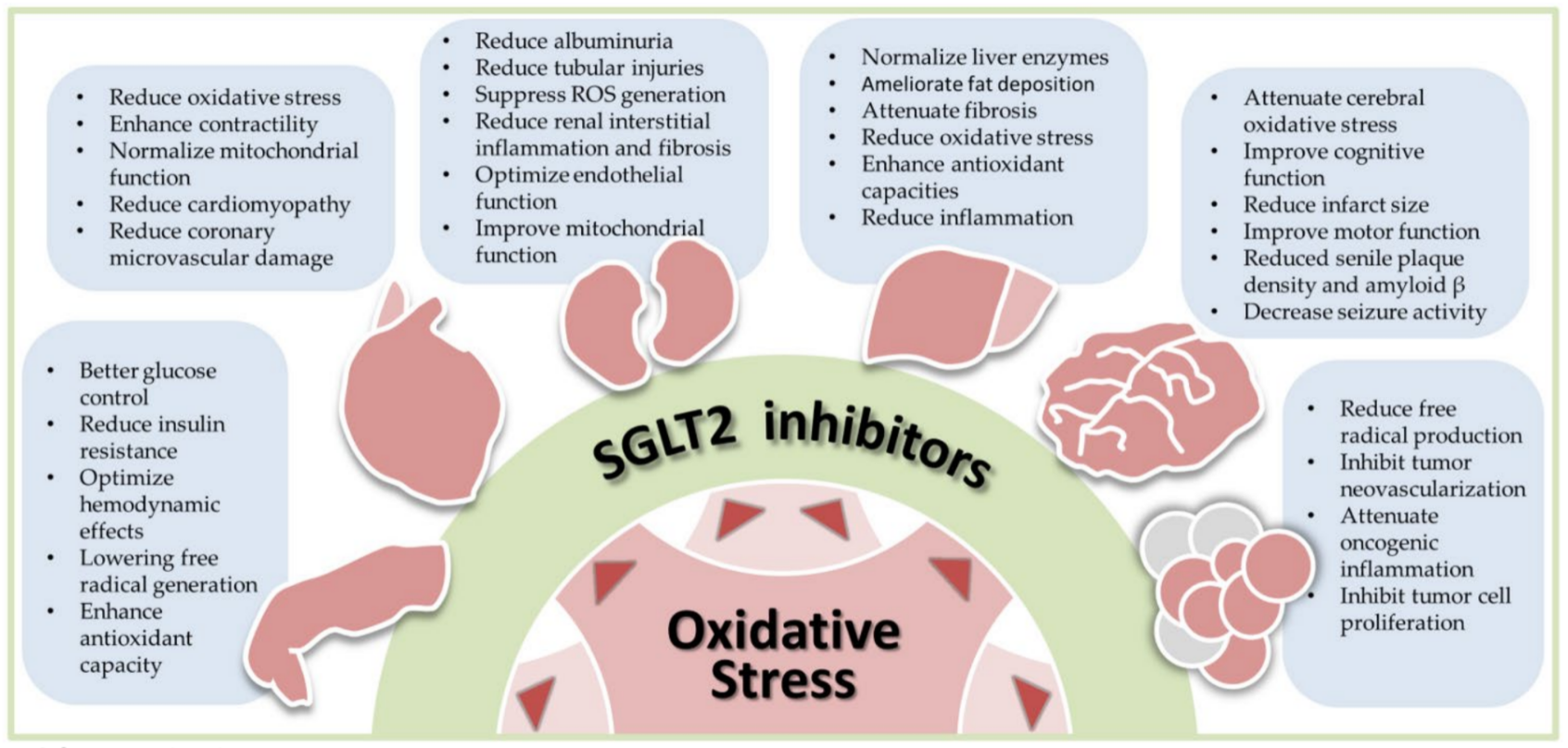

SGLT2 inhibitors have received great attention from scientists and clinicians. The pros and cons of SGTL2 inhibitors have been extensively reviewed in a plethora of papers [1][2][5][42][43][44]. Assessment on the research design, outcomes and limitations of large landmark trials on SGLT2 inhibitors have been thoroughly discussed [1][13][45][46] and are beyond the scope of this entry. This entry focuses on recent advances in SGLT2 inhibitor research from an antioxidant perspective. Researchers searched the Ovid MEDLINE, PubMed, Embase and Cochrane databases for SGLT2 inhibitors, antioxidants, oxidative stress, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, kidney, liver, neural disease, and cancers published up to 30 April 2021. Researchers will discuss how SGLT2 inhibitors reduce oxidative stress in human diseases. Although experimental and clinical evidence supporting SGLT2 inhibitors as antioxidants are not equally present in each disease discussed, researchers structured their entry in a diseases-specific fashion. By presenting this disease-specific entry, researchers hope scientists and medical professionals will better understand the antioxidant roles of SGLT2 inhibitors in the disease-of-interest and quickly find out the research gaps in their fields. Figure 1 illustrates the scope of this entry.

Figure 1. Antioxidant effects of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors in human diseases, including diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, nephropathy, liver diseases, neural disorders, and cancers. Oxidative stress is commonly seen in human diseases. By reducing oxidative stress, SGLT2 inhibitors exhibit the therapeutic potential in these diseases. The bullet points listed in each blue box summarize results of preclinical and clinical studies in each specific disease. ROS, reactive oxygen species.

2. SGLT2 Inhibitors as Antioxidants in Diabetes

T2DM is a major threat to human health, impacting 9.3% of adults globally in 2019, thus resulting in several microvascular and macrovascular complications, including retinopathy, nephropathy, peripheral arterial disease, and cardiovascular disease [47]. Oxidative stress is considered a major hallmark of the pathogenesis of T2DM and its complications. In patients with T2DM, hyperglycemia can upregulate chronic inflammation and increase reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, which ultimately causes endothelial dysfunction and vascular complications; conversely, increased oxidative stress and persistent inflammation can aggravate insulin resistance and exacerbate hyperglycemia in T2DM and prediabetes [48][49]. Furthermore, the dysregulation of mitochondrial oxidation and the complex interplay between nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidases, xanthine oxidase, endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), and AGEs contribute to the elevated oxidative stress and hence deteriorate systemic complications of T2DM [49][50][51][52]. To prevent complications and defer the progression of T2DM, appropriate treatment of hyperglycemia and inhibition of oxidative stress are crucial. Several strategies have been proposed to modulate oxidative stress and inflammation in T2DM, including dietary intervention and medications such as antihypertensives, statins, antiplatelets, probiotics, and glucose-lowering agents [49][53][54][55]. Among these interventions, SGLT2 inhibitors have emerged as newly recognized antioxidant agents, affording their effects not only via glucose control but also by lowering free radical generation and regulating the antioxidant systems such as SODs and GSH peroxidases [27][28][29]. In the following subsections, researchers will focus on the antioxidant mechanisms underlying SGLT2 inhibitors in T2DM, as well as their possible effects on insulin resistance and outcomes of T2DM.

2.1. The Antioxidant Mechanisms Underlying SGLT2 Inhibitors in T2DM

Accumulating evidence from experimental and clinical studies supports the antioxidant roles of SGLT2 inhibitors in T2DM, with mechanisms that involve both inhibition of free radical generation and regulation of antioxidant systems via direct modulative properties, as well as indirect influences from glucose-lowering and hemodynamic effects.

Several studies have described the mechanistic view of SGLT2 inhibitors in free radical suppression during T2DM. Steven et al. examined the antioxidative effects of empagliflozin in Zucker diabetic fatty rats, demonstrating that empagliflozin could prevent the development of systemic oxidative stress, AGE-receptor for AGEs (RAGE) signaling pathway, and inflammation by lowering glucose levels, restoring insulin sensitivity, and improving the redox status [24]. Other studies in diabetic mouse models indicated that SGLT2 inhibitors suppressed NADPH oxidase 4 (NOX4), enhanced Nrf2-heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1)-mediated oxidative stress response, regulated the Sestrin2-mediated adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase-mammalian target of rapamycin (AMPK-mTOR) signaling pathway, decreased oxidative stress, and therefore delivered renal, β cell mass, and cardiovascular benefits [25][56]. In a study utilizing human umbilical vein endothelial cells, SGLT2 inhibitors activated the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT)/eNOS signaling pathway, decreased free radical damage, and ameliorated endothelial dysfunction [57]. Additionally, the antioxidant effects of SGLT2 inhibitors involving other pro-oxidant enzymes and proinflammatory cytokines, such as monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), have been described in animal and in vitro studies [22][58]. Shao et al. and Sa-nguanmoo et al. reported that SGLT2 inhibitors attenuated mitochondrial dysfunction via several pathways, including PPARγ coactivator 1α and mitochondrial transcription factor A signaling in diabetic rat models, which also decreased free radical generation [59][60]. Moreover, in vivo and in vitro findings have indicated that the intrarenal hemodynamic effects and inhibition of the RAS by SGLT2 inhibitors can ameliorate oxidative stress. In clinical studies of dapagliflozin and canagliflozin, decreased 8-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) and oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) levels in patients with T2DM further corroborated the antioxidant effects of SGLT2 inhibitors [39][61].

Antioxidant systems are defense mechanisms against oxidative stress, and mechanistic evidence has indicated the role of SGLT2 inhibitors in antioxidant enhancement. Oshima et al. revealed that empagliflozin increased antioxidant proteins such as SOD2 and catalase in a diabetic rat model [28]. In addition, beneficial effects on manganese/copper/zinc-dependent SODs and GSH peroxidase were observed in SGLT2 inhibitor-treated animal models [29][39]. Improvements in GSH and GSH reductase profiles in leukocytes were documented in a prospective observational study assessing patients with T2DM [62].

Collectively, SGLT2 inhibitors have multifaceted antioxidant effects in T2DM, involving suppressing free radicals and enhancing the antioxidant system. Possible mechanisms include direct alleviation of mitochondrial dysfunction, modulation of pro-oxidant enzymes and proinflammatory cytokines, and upregulation of antioxidant proteins [25][28][29][56][57][58][59][60][62]. Moreover, SGLT2 inhibitors could indirectly ameliorate oxidative stress in T2DM by decreasing AGE-RAGE interactions, with glucose control and regulation of intrarenal hemodynamics and the RAS [24][39][61].

2.2. The Effects of SGLT2 Inhibitors on Insulin Resistance

Insulin resistance is a critical feature in the pathogenesis of T2DM, which also aggravates oxidative stress; conversely, oxidative stress exacerbates insulin resistance, accelerating the progression of prediabetes and T2DM [49]. Emerging investigations have indicated that SGLT2 inhibitors might influence insulin signal transduction, improve peripheral insulin sensitivity, and thus alleviate insulin resistance [63]. Combined with the antioxidant mechanisms mentioned above, SGLT2 inhibitors could disrupt the vicious cycle between insulin resistance and oxidative stress and are therefore an excellent therapeutic option.

The benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors on insulin resistance originate from multiple mechanisms. In patients with diabetes, Goto et al. evaluated the influence of empagliflozin treatment on insulin sensitivity of skeletal muscles; following a one-week regimen, noticeable improvement in insulin sensitivity was detected, which was attributed to a rapid correction of glucotoxicity [64]. Additional experimental and clinical studies have supported the benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors on β-cell function, insulin signaling, and insulin sensitivity via amelioration of glucotoxicity [65][66]. The effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on weight control and visceral fat lowering, attributed to glycosuria-related caloric deposition, are also crucial for insulin sensitivity. Studies in Japanese and Indian diabetic populations have demonstrated that SGLT2 inhibitors contribute to a reduction in body weight and visceral fat, improving insulin sensitivity via alleviation of lipotoxicity [67][68]. In animal models, SGLT2 inhibitors induced white adipose tissue browning and improved fat utilization via an M2 macrophage polarization-dependent mechanism, thereby increasing insulin sensitivity [69]. To maintain better glucose homeostasis and enhance insulin sensitivity, preservation of β-cell function is imperative, and SGLT2 inhibitors reportedly play vital roles in terms of this aspect. Robust clinical evidence [70][71] on the β-cell protection afforded by SGLT2 inhibitors has been documented, with several relevant mechanisms proposed, including deceleration of β cell death and regeneration of pancreatic islet cells via amelioration of glucotoxicity, lipotoxicity, inflammation, fibrosis, and oxidative damage [63][72]. Furthermore, Wei et al. reported that SGLT2 inhibitors induced β-cell self-replication, α-to-β cell conversion, and duct-derived β cell neogenesis in an animal model, partially mediated by the additional promotion of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) secretion [73]. Finally, the attenuative effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on oxidative stress and inflammatory responses are also crucial for restoring insulin sensitivity, as discussed above.

In conclusion, SGLT2 inhibitors can decrease insulin resistance via multiple mechanisms, including glucotoxicity correction, caloric disposition and lipotoxicity modulation, β cell preservation, and attenuation of oxidative stress and inflammation. Collectively, the antioxidant properties and insulin-sensitizing effects of SGLT2 inhibitors could disrupt the interplay between oxidative stress and insulin resistance in T2DM and serve as favorable therapeutic options.

2.3. The Antioxidant Effects of SGLT2 Inhibitors on T2DM Outcomes

With favorable results reported in large clinical trials such as the Empagliflozin Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients-Removing Excess Glucose (EMPA-REG OUTCOME) trial, the Dapagliflozin in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction (DAPA-HF) trial, the Dapagliflozin and Prevention of Adverse Outcomes in Chronic Kidney Disease (DAPA-CKD) trial, Canagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study (CANVAS), and the Canagliflozin and Renal Events in Diabetes with Established Nephropathy Clinical Evaluation (CREDENCE) trial, the cardiorenal protective benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors have been widely recognized. Notably, clinical guidelines recommend SGLT2 inhibitors as the glucose-lowering agent for patients with diabetes presenting a higher cardiovascular risk or renal insufficiency [13][74]. Besides metabolic, hemodynamic, and diuretic mechanisms, the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of SGLT2 inhibitors also contribute to their cardiorenal benefits [19]. Some clinical studies on SGLT2 inhibitors have directly assessed the link between antioxidant effects and their outcome benefits. In the Dapagliflozin Effectiveness on Vascular Endothelial Function and Glycemic Control (DEFENCE) trial, an open-label prospective blinded-endpoint study, patients with T2DM, previously treated with metformin, were randomized to receive either higher doses of metformin or metformin plus dapagliflozin; effects on endothelial function and oxidative stress, as determined by the flow-mediated dilation method and urinary 8-OHdG levels, respectively, were evaluated. After the 16-week study period, the dapagliflozin group demonstrated greater improvement in endothelial function, especially in patients with glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) > 7.0%, and urinary 8-OHdG levels were significantly lower in the dapagliflozin group [75]. In another open-label prospective study evaluating Japanese patients with chronic heart failure and T2DM, the effects of add-on canagliflozin on fat distribution, cardiac natriuretic peptides, renal function, endothelial function, and oxidative stress were examined. During the 12-month treatment period, renal function, endothelial function, and cardiac natriuretic peptides were all improved, and a decline in oxidative stress indicated by ox-LDL was observed [76]. In summary, SGLT2 inhibitors afford additional cardiorenal protection in T2DM, possibly attributed to the antioxidant properties, as supported by experimental and clinical evidence.

3. SGLT2 Inhibitors as Antioxidants in Heart Diseases

In patients with diabetes, aggressive blood sugar control can help prevent or improve small vessel disease (neuropathy, nephropathy, retinopathy), as well as delay the occurrence of nephropathy [77]. However, in diabetic patients with significant vascular diseases, including stroke, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and death due to cardiovascular disease, active blood sugar control may fail to reduce the risk of occurrence [77]. Previously, in addition to metformin, which may reduce myocardial infarction and heart failure, drugs such as sulfonylurea, thiazolidinedione, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors, and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists may increase the incidence of heart failure or present inconclusive results (no class effect) [78][79][80][81][82][83][84]. In contrast to previous oral glucose-lowering agents, SGLT2 inhibitors showed additional benefits in cardiovascular outcomes in three influential studies: the Dapagliflozin Effect on Cardiovascular Events-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 58 (DECLARE-TIMI 58) trial, the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial, and the CANVAS program [8][12][85]. Mounting evidence has revealed that the cardiac benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors may be independent of glycemic control. The DAPA-HF trial and cardiovascular and renal outcomes with empagliflozin in heart failure (EMPEROR-Reduced) trial demonstrated that among patients with heart failure and a reduced ejection fraction, the risk of worsening heart failure or cardiovascular death was lower in those who received SGLT2 inhibitors than in those who received the placebo, regardless of the presence or absence of diabetes [7][86]. In this entry, researchers focus on the relationship between SGLT2 inhibitors and oxidative stress in heart failure and discuss the potential antioxidant role of SGLT2 inhibitors.

3.1. Oxidative Stress, Diabetic Cardiomyopathy and Heart Failure

Heart failure and diabetes both present chronic low-grade inflammation. Cellular ion dysregulation, AMPK inactivation, and ROS production are relevant factors in the development of inflammation [87]. Inflammation may also lead to fibrosis, cell death, and cardiac remodeling. Hence, inhibiting inflammation may be a crucial mechanism for preventing and treating diabetes-related heart failure. Early increased oxidative stress is prominent in heart failure and T2DM pathogenesis [88][89]. Highly reactive ROS can oxidize several proteins, thereby altering the function of these proteins. Furthermore, ROS is an upstream driver of endothelial dysfunction associated with heart failure by increasing the uncoupling of nitric oxide synthase to convert nitric oxide into peroxynitrite [90][91][92][93]. ROS have several detrimental effects on the myocardium, inducing cardiomyocyte electrophysiologic and contractile dysfunction, mitochondrial dysfunction, and increased cardiac fibrosis [94]. Therefore, reducing ROS normalizes the function of many proteins in cardiomyocytes, which may prevent the development of heart failure.

Both heart failure and diabetic cardiomyopathy result in an energy crisis, which is manifested by a decrease in the cardiac phosphocreatine (PCr) to adenosine triphosphate (ATP) ratio. Accordingly, cell low-energy sensors, including sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) and AMPK, are activated. SIRT1 and AMPK are activated not only by starvation but also by cellular stressors, including hypoxia, ROS, injured organelles, and misfolded proteins [95]. SIRT1 eliminates oxidative stress by enhancing antioxidant activity, directly reduces the inflammatory response to oxygen free radicals, and reduces the lethality of oxidative stress [96]. AMPK maintains mitochondrial function, thereby reducing ROS formation and attenuating proinflammatory and pro-apoptotic responses [97]. AMPK activity is increased in failed cardiomyocytes [98]. AMPK acts as an energy sensor and activates catabolism by increasing glucose uptake and glycolysis while impairing anabolic reaction [99]. Targeting the AMPK pathway by increasing AMPK activity has been shown to combat cardiac hypertrophy and myocardial failure [100]. In addition, AMPK activity can be associated with non-metabolic cellular processes, including regulation of vascular tone and inhibition of inflammation [99][101][102].

AGEs mainly originate from the rearrangement of early glycation products [103]. AGEs accumulate in plasma and vascular tissues and directly interact with the extracellular matrix to induce arterial stiffness and reduced elasticity [104]. RAGEs on the surface of endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, and monocytes promote oxidative stress and cause inflammation and fibrosis of the vessel [105][106]. Activation of AGE-RAGE signaling is associated with an increased risk of acute coronary syndrome and heart failure [107].

3.2. The Potential Antioxidant Effects of SGLT2 Inhibitors in Heart Failure

Several mechanisms have been proposed for the cardiovascular effects of SGLT2 inhibitors, including reduced blood pressure, cardiac preload and afterload, plasma volume, increased hematocrit, increased myocardial energetic efficiency, inhibition of Na+/H+ exchanger (NHE), and decreased oxidative stress [1][20][108]. This entry highlights the potential antioxidant effects of SGLT2 inhibitors in heart failure.

Notably, the effect of SGLT2 inhibitors in stimulating the activity of low-energy sensors is not mediated by the SGLT2 protein in cells, as this effect can also be observed in organs that do not express SGLT2 [37][109]. SGLT2 inhibitors activate SIRT1/AMPK and inhibit AKT/mTOR signaling; therefore, they can promote autophagy beyond its effect on glucose or insulin [109][110][111]. In addition, the activation of SIRT1/AMPK and inhibition of AKT/mTOR signal transduction mediated by SGLT2 inhibitors can result in reduced oxidative stress, normalization of mitochondrial structure and function, inhibition of inflammation, reduction of coronary microvascular damage, enhancement of contractility, and reduced incidence of cardiomyopathy [112]. Furthermore, the activation of AMPK/SIRT1 and autophagic flux can be associated with the downregulation of ion exchangers, reportedly involved in the pathogenesis of diabetic cardiomyopathy [113]. Finally, the enhancement of HIF-1α/HIF-2αsignaling by SGLT2 inhibitors may amplify the autophagic flux enhanced by AMPK/SIRT1, which may be an important contribution to the cardiac benefits of these drugs, which are not observed with other glucose-lowering agents [114].

Reportedly, reduced AGE production and inhibition of the AGE-RAGE axis, along with the parallel reduction of oxidative stress following ipragliflozin treatment, improved the endothelial function of diabetic mice [115]. Empagliflozin improved the cardiac diastolic function in a female rodent model of diabetes without normalizing myocardial AGE levels [116]. In cultured H9C2 cells, a hypoxia/reoxygenation model, empagliflozin increased cell viability and maintained ATP levels [117]. These effects were equally present in myocytes stimulated by AGE, and empagliflozin did not alter the expression level of RAGE; this suggested that these pro-survival mechanisms of empagliflozin were not mediated through AGE/RAGE signaling. The importance of AGEs and AGE-RAGE signaling as mediators of SGLT2 inhibitor effects in the human heart remains elusive.

In patients with diabetes, hyperglycemia can promote glucose uptake by cardiomyocytes, which in turn impairs cardiac function [118]. It has been reported that glucose toxicity increases cardiac oxidative stress and exacerbates myocardial injury in patients with T2DM [119]. SGLT2 inhibitors can prevent the absorption of excess glucose by the heart. These inhibitors enhance the β-hydroxybutyrate content and convert the energy supply from fatty acids and glucose to ketones, thus increasing the metabolic efficiency of the myocardium and decreasing oxygen consumption [120]. A study using a non-diabetic porcine model with myocardial infarction revealed that empagliflozin increased myocardial ketone consumption while simultaneously decreasing glucose consumption. Increased myocardial energetics leads to reversed anatomical, metabolic, and neurohormonal remodeling [46]. Although animal studies have confirmed this hypothesis, supportive clinical data are still lacking. In an attempt to translate these preclinical results into the clinical arena, a recent clinical trial using empagliflozin (EMPA-TROPISM trial) was conducted in non-diabetic patients with heart failure [121].

In summary, several lines of evidence emphasize the antioxidant roles of SGLT2 inhibitors in cardiovascular diseases. Although this evidence supports the cardioprotective effects of SGLT2 inhibitors observed in large clinical trials, additional research is critical to further elucidate regulatory pathways and explore novel therapeutic targets that may present synergistic effects with SGLT2 inhibitors in affording cardioprotection.

References

- Cowie, M.R.; Fisher, M. Sglt2 inhibitors: Mechanisms of cardiovascular benefit beyond glycaemic control. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 17, 761–772.

- Alicic, R.Z.; Johnson, E.J.; Tuttle, K.R. Sglt2 inhibition for the prevention and treatment of diabetic kidney disease: A review. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2018, 72, 267–277.

- Bailey, C.J. Uric acid and the cardio-renal effects of sglt2 inhibitors. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2019, 21, 1291–1298.

- Thomas, M.C.; Cherney, D.Z.I. The actions of sglt2 inhibitors on metabolism, renal function and blood pressure. Diabetologia 2018, 61, 2098–2107.

- Saisho, Y. Sglt2 inhibitors: The star in the treatment of type 2 diabetes? Diseases 2020, 8, 14.

- Cannon, C.P.; McGuire, D.K.; Pratley, R.; Dagogo-Jack, S.; Mancuso, J.; Huyck, S.; Charbonnel, B.; Shih, W.J.; Gallo, S.; Masiukiewicz, U.; et al. Design and baseline characteristics of the evaluation of ertugliflozin efficacy and safety cardiovascular outcomes trial (vertis-cv). Am. Heart J. 2018, 206, 11–23.

- McMurray, J.J.V.; Solomon, S.D.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Kober, L.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Martinez, F.A.; Ponikowski, P.; Sabatine, M.S.; Anand, I.S.; Belohlavek, J.; et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1995–2008.

- Neal, B.; Perkovic, V.; Mahaffey, K.W.; de Zeeuw, D.; Fulcher, G.; Erondu, N.; Shaw, W.; Law, G.; Desai, M.; Matthews, D.R.; et al. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 644–657.

- Perkovic, V.; de Zeeuw, D.; Mahaffey, K.W.; Fulcher, G.; Erondu, N.; Shaw, W.; Barrett, T.D.; Weidner-Wells, M.; Deng, H.; Matthews, D.R.; et al. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: Results from the canvas program randomised clinical trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018, 6, 691–704.

- Wiviott, S.D.; Raz, I.; Bonaca, M.P.; Mosenzon, O.; Kato, E.T.; Cahn, A.; Silverman, M.G.; Zelniker, T.A.; Kuder, J.F.; Murphy, S.A.; et al. Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 347–357.

- Yu, Y.; Tse, K.Y.; Lee, H.H.Y.; Chow, K.L.; Tsang, H.W.; Wong, R.W.C.; Cheung, E.T.Y.; Cheuk, W.; Lee, V.W.K.; Chan, W.K.; et al. Predictive biomarkers and tumor microenvironment in female genital melanomas: A multi-institutional study of 55 cases. Mod. Pathol. 2020, 33, 138–152.

- Zinman, B.; Wanner, C.; Lachin, J.M.; Fitchett, D.; Bluhmki, E.; Hantel, S.; Mattheus, M.; Devins, T.; Johansen, O.E.; Woerle, H.J.; et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 2117–2128.

- Buse, J.B.; Wexler, D.J.; Tsapas, A.; Rossing, P.; Mingrone, G.; Mathieu, C.; D’Alessio, D.A.; Davies, M.J. 2019 update to: Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report by the american diabetes association (ada) and the european association for the study of diabetes (easd). Diabetologia 2020, 63, 221–228.

- Lee, W.C.; Chau, Y.Y.; Ng, H.Y.; Chen, C.H.; Wang, P.W.; Liou, C.W.; Lin, T.K.; Chen, J.B. Empagliflozin protects hk-2 cells from high glucose-mediated injuries via a mitochondrial mechanism. Cells 2019, 8, 1085.

- Liu, X.; Xu, C.; Xu, L.; Li, X.; Sun, H.; Xue, M.; Li, T.; Yu, X.; Sun, B.; Chen, L. Empagliflozin improves diabetic renal tubular injury by alleviating mitochondrial fission via ampk/sp1/pgam5 pathway. Metabolism 2020, 111, 154334.

- Lee, Y.H.; Kim, S.H.; Kang, J.M.; Heo, J.H.; Kim, D.J.; Park, S.H.; Sung, M.; Kim, J.; Oh, J.; Yang, D.H.; et al. Empagliflozin attenuates diabetic tubulopathy by improving mitochondrial fragmentation and autophagy. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2019, 317, F767–F780.

- Margonato, D.; Galati, G.; Mazzetti, S.; Cannistraci, R.; Perseghin, G.; Margonato, A.; Mortara, A. Renal protection: A leading mechanism for cardiovascular benefit in patients treated with sglt2 inhibitors. Heart Fail. Rev. 2021, 26, 337–345.

- Scheen, A.J. Effect of sglt2 inhibitors on the sympathetic nervous system and blood pressure. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2019, 21, 70.

- Zelniker, T.A.; Braunwald, E. Mechanisms of cardiorenal effects of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors: Jacc state-of-the-art review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 75, 422–434.

- Verma, S.; McMurray, J.J.V. Sglt2 inhibitors and mechanisms of cardiovascular benefit: A state-of-the-art review. Diabetologia 2018, 61, 2108–2117.

- Li, C.; Zhang, J.; Xue, M.; Li, X.; Han, F.; Liu, X.; Xu, L.; Lu, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Li, T.; et al. Sglt2 inhibition with empagliflozin attenuates myocardial oxidative stress and fibrosis in diabetic mice heart. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2019, 18, 15.

- Ishibashi, Y.; Matsui, T.; Yamagishi, S. Tofogliflozin, a highly selective inhibitor of sglt2 blocks proinflammatory and proapoptotic effects of glucose overload on proximal tubular cells partly by suppressing oxidative stress generation. Horm. Metab. Res. 2016, 48, 191–195.

- Sies, H. Oxidative stress: A concept in redox biology and medicine. Redox Biol. 2015, 4, 180–183.

- Steven, S.; Oelze, M.; Hanf, A.; Kröller-Schön, S.; Kashani, F.; Roohani, S.; Welschof, P.; Kopp, M.; Gödtel-Armbrust, U.; Xia, N.; et al. The sglt2 inhibitor empagliflozin improves the primary diabetic complications in zdf rats. Redox Biol. 2017, 13, 370–385.

- Terami, N.; Ogawa, D.; Tachibana, H.; Hatanaka, T.; Wada, J.; Nakatsuka, A.; Eguchi, J.; Horiguchi, C.S.; Nishii, N.; Yamada, H.; et al. Long-term treatment with the sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor, dapagliflozin, ameliorates glucose homeostasis and diabetic nephropathy in db/db mice. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e100777.

- Tahara, A.; Kurosaki, E.; Yokono, M.; Yamajuku, D.; Kihara, R.; Hayashizaki, Y.; Takasu, T.; Imamura, M.; Li, Q.; Tomiyama, H.; et al. Effects of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 selective inhibitor ipragliflozin on hyperglycaemia, oxidative stress, inflammation and liver injury in streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetic rats. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2014, 66, 975–987.

- Yaribeygi, H.; Atkin, S.L.; Butler, A.E.; Sahebkar, A. Sodium-glucose cotransporter inhibitors and oxidative stress: An update. J. Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 3231–3237.

- Oshima, H.; Miki, T.; Kuno, A.; Mizuno, M.; Sato, T.; Tanno, M.; Yano, T.; Nakata, K.; Kimura, Y.; Abe, K.; et al. Empagliflozin, an sglt2 inhibitor, reduced the mortality rate after acute myocardial infarction with modification of cardiac metabolomes and antioxidants in diabetic rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2019, 368, 524–534.

- Osorio, H.; Coronel, I.; Arellano, A.; Pacheco, U.; Bautista, R.; Franco, M.; Escalante, B. Sodium-glucose cotransporter inhibition prevents oxidative stress in the kidney of diabetic rats. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2012, 2012, 542042.

- Scafoglio, C.R.; Villegas, B.; Abdelhady, G.; Bailey, S.T.; Liu, J.; Shirali, A.S.; Wallace, W.D.; Magyar, C.E.; Grogan, T.R.; Elashoff, D.; et al. Sodium-glucose transporter 2 is a diagnostic and therapeutic target for early-stage lung adenocarcinoma. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018, 10, eaat5933.

- Koepsell, H. The na(+)-d-glucose cotransporters sglt1 and sglt2 are targets for the treatment of diabetes and cancer. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 170, 148–165.

- Komatsu, S.; Nomiyama, T.; Numata, T.; Kawanami, T.; Hamaguchi, Y.; Iwaya, C.; Horikawa, T.; Fujimura-Tanaka, Y.; Hamanoue, N.; Motonaga, R.; et al. Sglt2 inhibitor ipragliflozin attenuates breast cancer cell proliferation. Endocr. J. 2020, 67, 99–106.

- Kaji, K.; Nishimura, N.; Seki, K.; Sato, S.; Saikawa, S.; Nakanishi, K.; Furukawa, M.; Kawaratani, H.; Kitade, M.; Moriya, K.; et al. Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor canagliflozin attenuates liver cancer cell growth and angiogenic activity by inhibiting glucose uptake. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 142, 1712–1722.

- Villani, L.A.; Smith, B.K.; Marcinko, K.; Ford, R.J.; Broadfield, L.A.; Green, A.E.; Houde, V.P.; Muti, P.; Tsakiridis, T.; Steinberg, G.R. The diabetes medication canagliflozin reduces cancer cell proliferation by inhibiting mitochondrial complex-i supported respiration. Mol. Metab. 2016, 5, 1048–1056.

- Ojima, A.; Matsui, T.; Nishino, Y.; Nakamura, N.; Yamagishi, S. Empagliflozin, an inhibitor of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 exerts anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects on experimental diabetic nephropathy partly by suppressing ages-receptor axis. Horm. Metab. Res. 2015, 47, 686–692.

- Han, J.H.; Oh, T.J.; Lee, G.; Maeng, H.J.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, K.M.; Choi, S.H.; Jang, H.C.; Lee, H.S.; Park, K.S.; et al. The beneficial effects of empagliflozin, an sglt2 inhibitor, on atherosclerosis in apoe (-/-) mice fed a western diet. Diabetologia 2017, 60, 364–376.

- Vallon, V.; Rose, M.; Gerasimova, M.; Satriano, J.; Platt, K.A.; Koepsell, H.; Cunard, R.; Sharma, K.; Thomson, S.C.; Rieg, T. Knockout of na-glucose transporter sglt2 attenuates hyperglycemia and glomerular hyperfiltration but not kidney growth or injury in diabetes mellitus. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2013, 304, F156–F167.

- Yaribeygi, H.; Butler, A.E.; Atkin, S.L.; Katsiki, N.; Sahebkar, A. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and inflammation in chronic kidney disease: Possible molecular pathways. J. Cell Physiol. 2018, 234, 223–230.

- Shin, S.J.; Chung, S.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, E.M.; Yoo, Y.H.; Kim, J.W.; Ahn, Y.B.; Kim, E.S.; Moon, S.D.; Kim, M.J.; et al. Effect of sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor, dapagliflozin, on renal renin-angiotensin system in an animal model of type 2 diabetes. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165703.

- Reuter, S.; Gupta, S.C.; Chaturvedi, M.M.; Aggarwal, B.B. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer: How are they linked? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 49, 1603–1616.

- Dandekar, A.; Mendez, R.; Zhang, K. Cross talk between er stress, oxidative stress, and inflammation in health and disease. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015, 1292, 205–214.

- Singh, M.; Kumar, A. Risks associated with sglt2 inhibitors: An overview. Curr. Drug Saf. 2018, 13, 84–91.

- Filippas-Ntekouan, S.; Filippatos, T.D.; Elisaf, M.S. Sglt2 inhibitors: Are they safe? Postgrad. Med. 2018, 130, 72–82.

- Vardeny, O. The sweet spot: Heart failure prevention with sglt2 inhibitors. Am. J. Med. 2020, 133, 182–185.

- Lytvyn, Y.; Bjornstad, P.; Udell, J.A.; Lovshin, J.A.; Cherney, D.Z.I. Sodium glucose cotransporter-2 inhibition in heart failure: Potential mechanisms, clinical applications, and summary of clinical trials. Circulation 2017, 136, 1643–1658.

- Rastogi, A.; Bhansali, A. Sglt2 inhibitors through the windows of empa-reg and canvas trials: A review. Diabetes Ther. 2017, 8, 1245–1251.

- Saeedi, P.; Petersohn, I.; Salpea, P.; Malanda, B.; Karuranga, S.; Unwin, N.; Colagiuri, S.; Guariguata, L.; Motala, A.A.; Ogurtsova, K.; et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the international diabetes federation diabetes atlas, 9(th) edition. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 157, 107843.

- Rehman, K.; Akash, M.S.H. Mechanism of generation of oxidative stress and pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus: How are they interlinked? J. Cell Biochem. 2017, 118, 3577–3585.

- Luc, K.; Schramm-Luc, A.; Guzik, T.J.; Mikolajczyk, T.P. Oxidative stress and inflammatory markers in prediabetes and diabetes. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2019, 70, 809–824.

- Anderson, E.J.; Lustig, M.E.; Boyle, K.E.; Woodlief, T.L.; Kane, D.A.; Lin, C.T.; Price, J.W., 3rd; Kang, L.; Rabinovitch, P.S.; Szeto, H.H.; et al. Mitochondrial h2o2 emission and cellular redox state link excess fat intake to insulin resistance in both rodents and humans. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 573–581.

- Jansen, F.; Yang, X.; Franklin, B.S.; Hoelscher, M.; Schmitz, T.; Bedorf, J.; Nickenig, G.; Werner, N. High glucose condition increases nadph oxidase activity in endothelial microparticles that promote vascular inflammation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2013, 98, 94–106.

- Wan, A.; Rodrigues, B. Endothelial cell-cardiomyocyte crosstalk in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc. Res. 2016, 111, 172–183.

- Wenclewska, S.; Szymczak-Pajor, I.; Drzewoski, J.; Bunk, M.; Śliwińska, A. Vitamin d supplementation reduces both oxidative DNA damage and insulin resistance in the elderly with metabolic disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2891.

- He, L.; Zhang, G.; Wei, M.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, W.; Peng, Q.; Meng, G. Effect of individualized dietary intervention on oxidative stress in patients with type 2 diabetes complicated by tuberculosis in xinjiang, china. Diabetes Ther. 2019, 10, 2095–2105.

- Bordalo Tonucci, L.; Dos Santos, K.M.; De Luces Fortes Ferreira, C.L.; Ribeiro, S.M.; De Oliveira, L.L.; Martino, H.S. Gut microbiota and probiotics: Focus on diabetes mellitus. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 2296–2309.

- Sun, X.; Han, F.; Lu, Q.; Li, X.; Ren, D.; Zhang, J.; Han, Y.; Xiang, Y.K.; Li, J. Empagliflozin ameliorates obesity-related cardiac dysfunction by regulating sestrin2-mediated ampk-mtor signaling and redox homeostasis in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Diabetes 2020, 69, 1292–1305.

- Li, C.Y.; Wang, L.X.; Dong, S.S.; Hong, Y.; Zhou, X.H.; Zheng, W.W.; Zheng, C. Phlorizin exerts direct protective effects on palmitic acid (pa)-induced endothelial dysfunction by activating the pi3k/akt/enos signaling pathway and increasing the levels of nitric oxide (no). Med. Sci. Monit. Basic Res. 2018, 24, 1–9.

- Kawanami, D.; Matoba, K.; Takeda, Y.; Nagai, Y.; Akamine, T.; Yokota, T.; Sango, K.; Utsunomiya, K. Sglt2 inhibitors as a therapeutic option for diabetic nephropathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1083.

- Shao, Q.; Meng, L.; Lee, S.; Tse, G.; Gong, M.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Li, G.; Liu, T. Empagliflozin, a sodium glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitor, alleviates atrial remodeling and improves mitochondrial function in high-fat diet/streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2019, 18, 165.

- Sa-Nguanmoo, P.; Tanajak, P.; Kerdphoo, S.; Jaiwongkam, T.; Pratchayasakul, W.; Chattipakorn, N.; Chattipakorn, S.C. Sglt2-inhibitor and dpp-4 inhibitor improve brain function via attenuating mitochondrial dysfunction, insulin resistance, inflammation, and apoptosis in hfd-induced obese rats. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2017, 333, 43–50.

- Tapia, E.; Sánchez-Lozada, L.G.; García-Niño, W.R.; García, E.; Cerecedo, A.; García-Arroyo, F.E.; Osorio, H.; Arellano, A.; Cristóbal-García, M.; Loredo, M.L.; et al. Curcumin prevents maleate-induced nephrotoxicity: Relation to hemodynamic alterations, oxidative stress, mitochondrial oxygen consumption and activity of respiratory complex i. Free Radic. Res. 2014, 48, 1342–1354.

- Iannantuoni, F.; A, M.d.M.; Diaz-Morales, N.; Falcon, R.; Bañuls, C.; Abad-Jimenez, Z.; Victor, V.M.; Hernandez-Mijares, A.; Rovira-Llopis, S. The sglt2 inhibitor empagliflozin ameliorates the inflammatory profile in type 2 diabetic patients and promotes an antioxidant response in leukocytes. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1814.

- Yaribeygi, H.; Sathyapalan, T.; Maleki, M.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Sahebkar, A. Molecular mechanisms by which sglt2 inhibitors can induce insulin sensitivity in diabetic milieu: A mechanistic review. Life Sci. 2020, 240, 117090.

- Goto, Y.; Otsuka, Y.; Ashida, K.; Nagayama, A.; Hasuzawa, N.; Iwata, S.; Hara, K.; Tsuruta, M.; Wada, N.; Motomura, S.; et al. Improvement of skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity by 1 week of sglt2 inhibitor use. Endocr. Connect. 2020, 9, 599–606.

- Ferrannini, E.; Muscelli, E.; Frascerra, S.; Baldi, S.; Mari, A.; Heise, T.; Broedl, U.C.; Woerle, H.J. Metabolic response to sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition in type 2 diabetic patients. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 499–508.

- Kern, M.; Klöting, N.; Mark, M.; Mayoux, E.; Klein, T.; Blüher, M. The sglt2 inhibitor empagliflozin improves insulin sensitivity in db/db mice both as monotherapy and in combination with linagliptin. Metabolism 2016, 65, 114–123.

- Koike, Y.; Shirabe, S.I.; Maeda, H.; Yoshimoto, A.; Arai, K.; Kumakura, A.; Hirao, K.; Terauchi, Y. Effect of canagliflozin on the overall clinical state including insulin resistance in japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 149, 140–146.

- Singh, A.K.; Unnikrishnan, A.G.; Zargar, A.H.; Kumar, A.; Das, A.K.; Saboo, B.; Sinha, B.; Gangopadhyay, K.K.; Talwalkar, P.G.; Ghosal, S.; et al. Evidence-based consensus on positioning of sglt2i in type 2 diabetes mellitus in indians. Diabetes Ther. 2019, 10, 393–428.

- Xu, L.; Ota, T. Emerging roles of sglt2 inhibitors in obesity and insulin resistance: Focus on fat browning and macrophage polarization. Adipocyte 2018, 7, 121–128.

- Al Jobori, H.; Daniele, G.; Adams, J.; Cersosimo, E.; Solis-Herrera, C.; Triplitt, C.; DeFronzo, R.A.; Abdul-Ghani, M. Empagliflozin treatment is associated with improved β-cell function in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 103, 1402–1407.

- Takahara, M.; Shiraiwa, T.; Matsuoka, T.A.; Katakami, N.; Shimomura, I. Ameliorated pancreatic β cell dysfunction in type 2 diabetic patients treated with a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor ipragliflozin. Endocr. J. 2015, 62, 77–86.

- Cheng, S.T.; Chen, L.; Li, S.Y.; Mayoux, E.; Leung, P.S. The effects of empagliflozin, an sglt2 inhibitor, on pancreatic β-cell mass and glucose homeostasis in type 1 diabetes. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147391.

- Wei, R.; Cui, X.; Feng, J.; Gu, L.; Lang, S.; Wei, T.; Yang, J.; Liu, J.; Le, Y.; Wang, H.; et al. Dapagliflozin promotes beta cell regeneration by inducing pancreatic endocrine cell phenotype conversion in type 2 diabetic mice. Metabolism 2020, 111, 154324.

- de Boer, I.H.; Caramori, M.L.; Chan, J.C.; Heerspink, H.J.; Hurst, C.; Khunti, K.; Liew, A.; Michos, E.D.; Navaneethan, S.D.; Olowu, W.A.; et al. Kdigo 2020 clinical practice guideline for diabetes management in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2020, 98, S1–S115.

- Shigiyama, F.; Kumashiro, N.; Miyagi, M.; Ikehara, K.; Kanda, E.; Uchino, H.; Hirose, T. Effectiveness of dapagliflozin on vascular endothelial function and glycemic control in patients with early-stage type 2 diabetes mellitus: Defence study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2017, 16, 84.

- Sezai, A.; Sekino, H.; Unosawa, S.; Taoka, M.; Osaka, S.; Tanaka, M. Canagliflozin for japanese patients with chronic heart failure and type ii diabetes. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2019, 18, 76.

- Marshall, S.M.; Flyvbjerg, A. Prevention and early detection of vascular complications of diabetes. BMJ 2006, 333, 475–480.

- Romero, S.P.; Andrey, J.L.; Garcia-Egido, A.; Escobar, M.A.; Perez, V.; Corzo, R.; Garcia-Domiguez, G.J.; Gomez, F. Metformin therapy and prognosis of patients with heart failure and new-onset diabetes mellitus. A propensity-matched study in the community. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 166, 404–412.

- UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Uk Prospective Diabetes Study 33. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes. Lancet 1998, 352, 837–853.

- Phung, O.J.; Schwartzman, E.; Allen, R.W.; Engel, S.S.; Rajpathak, S.N. Sulphonylureas and risk of cardiovascular disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet. Med. 2013, 30, 1160–1171.

- Home, P.D.; Pocock, S.J.; Beck-Nielsen, H.; Gomis, R.; Hanefeld, M.; Jones, N.P.; Komajda, M.; McMurray, J.J.; Group, R.S. Rosiglitazone evaluated for cardiovascular outcomes--an interim analysis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 28–38.

- Mahaffey, K.W.; Hafley, G.; Dickerson, S.; Burns, S.; Tourt-Uhlig, S.; White, J.; Newby, L.K.; Komajda, M.; McMurray, J.; Bigelow, R.; et al. Results of a reevaluation of cardiovascular outcomes in the record trial. Am. Heart J. 2013, 166, 240–249.e1.

- Green, J.B.; Bethel, M.A.; Armstrong, P.W.; Buse, J.B.; Engel, S.S.; Garg, J.; Josse, R.; Kaufman, K.D.; Koglin, J.; Korn, S.; et al. Effect of sitagliptin on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 232–242.

- Scirica, B.M.; Braunwald, E.; Raz, I.; Cavender, M.A.; Morrow, D.A.; Jarolim, P.; Udell, J.A.; Mosenzon, O.; Im, K.; Umez-Eronini, A.A.; et al. Heart failure, saxagliptin, and diabetes mellitus: Observations from the savor-timi 53 randomized trial. Circulation 2014, 130, 1579–1588.

- Akinci, B. Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. Reply. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1881.

- Packer, M.; Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Pocock, S.J.; Carson, P.; Januzzi, J.; Verma, S.; Tsutsui, H.; Brueckmann, M.; et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with empagliflozin in heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1413–1424.

- Frati, G.; Schirone, L.; Chimenti, I.; Yee, D.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; Volpe, M.; Sciarretta, S. An overview of the inflammatory signalling mechanisms in the myocardium underlying the development of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc. Res. 2017, 113, 378–388.

- Dey, S.; DeMazumder, D.; Sidor, A.; Foster, D.B.; O’Rourke, B. Mitochondrial ros drive sudden cardiac death and chronic proteome remodeling in heart failure. Circ. Res. 2018, 123, 356–371.

- Shah, M.S.; Brownlee, M. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of cardiovascular disorders in diabetes. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 1808–1829.

- Paulus, W.J.; Tschope, C. A novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Comorbidities drive myocardial dysfunction and remodeling through coronary microvascular endothelial inflammation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 62, 263–271.

- Joshi, M.; Kotha, S.R.; Malireddy, S.; Selvaraju, V.; Satoskar, A.R.; Palesty, A.; McFadden, D.W.; Parinandi, N.L.; Maulik, N. Conundrum of pathogenesis of diabetic cardiomyopathy: Role of vascular endothelial dysfunction, reactive oxygen species, and mitochondria. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2014, 386, 233–249.

- Munzel, T.; Gori, T.; Keaney, J.F., Jr.; Maack, C.; Daiber, A. Pathophysiological role of oxidative stress in systolic and diastolic heart failure and its therapeutic implications. Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 2555–2564.

- Belch, J.J.; Bridges, A.B.; Scott, N.; Chopra, M. Oxygen free radicals and congestive heart failure. Br. Heart J. 1991, 65, 245–248.

- van der Pol, A.; van Gilst, W.H.; Voors, A.A.; van der Meer, P. Treating oxidative stress in heart failure: Past, present and future. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 425–435.

- Packer, M. Sglt2 inhibitors produce cardiorenal benefits by promoting adaptive cellular reprogramming to induce a state of fasting mimicry: A paradigm shift in understanding their mechanism of action. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 508–511.

- Alcendor, R.R.; Gao, S.; Zhai, P.; Zablocki, D.; Holle, E.; Yu, X.; Tian, B.; Wagner, T.; Vatner, S.F.; Sadoshima, J. Sirt1 regulates aging and resistance to oxidative stress in the heart. Circ. Res. 2007, 100, 1512–1521.

- Meijles, D.N.; Zoumpoulidou, G.; Markou, T.; Rostron, K.A.; Patel, R.; Lay, K.; Handa, B.S.; Wong, B.; Sugden, P.H.; Clerk, A. The cardiomyocyte “redox rheostat”: Redox signalling via the ampk-mtor axis and regulation of gene and protein expression balancing survival and death. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2019, 129, 118–129.

- Tian, R.; Musi, N.; D’Agostino, J.; Hirshman, M.F.; Goodyear, L.J. Increased adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase activity in rat hearts with pressure-overload hypertrophy. Circulation 2001, 104, 1664–1669.

- Beauloye, C.; Bertrand, L.; Horman, S.; Hue, L. Ampk activation, a preventive therapeutic target in the transition from cardiac injury to heart failure. Cardiovasc. Res. 2011, 90, 224–233.

- Gelinas, R.; Mailleux, F.; Dontaine, J.; Bultot, L.; Demeulder, B.; Ginion, A.; Daskalopoulos, E.P.; Esfahani, H.; Dubois-Deruy, E.; Lauzier, B.; et al. Ampk activation counteracts cardiac hypertrophy by reducing o-glcnacylation. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 374.

- Cordero, M.D.; Williams, M.R.; Ryffel, B. Amp-activated protein kinase regulation of the nlrp3 inflammasome during aging. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 29, 8–17.

- He, C.; Li, H.; Viollet, B.; Zou, M.H.; Xie, Z. Ampk suppresses vascular inflammation in vivo by inhibiting signal transducer and activator of transcription-1. Diabetes 2015, 64, 4285–4297.

- Vlassara, H.; Bucala, R. Recent progress in advanced glycation and diabetic vascular disease: Role of advanced glycation end product receptors. Diabetes 1996, 45 (Suppl. 3), S65–S66.

- Yan, S.F.; Ramasamy, R.; Naka, Y.; Schmidt, A.M. Glycation, inflammation, and rage: A scaffold for the macrovascular complications of diabetes and beyond. Circ. Res. 2003, 93, 1159–1169.

- Yamagishi, S.; Nakamura, K.; Matsui, T.; Noda, Y.; Imaizumi, T. Receptor for advanced glycation end products (rage): A novel therapeutic target for diabetic vascular complication. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2008, 14, 487–495.

- Goldin, A.; Beckman, J.A.; Schmidt, A.M.; Creager, M.A. Advanced glycation end products: Sparking the development of diabetic vascular injury. Circulation 2006, 114, 597–605.

- Paradela-Dobarro, B.; Agra, R.M.; Alvarez, L.; Varela-Roman, A.; Garcia-Acuna, J.M.; Gonzalez-Juanatey, J.R.; Alvarez, E.; Garcia-Seara, F.J. The different roles for the advanced glycation end products axis in heart failure and acute coronary syndrome settings. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2019, 29, 1050–1060.

- Brito, D.; Bettencourt, P.; Carvalho, D.; Ferreira, J.; Fontes-Carvalho, R.; Franco, F.; Moura, B.; Silva-Cardoso, J.C.; de Melo, R.T.; Fonseca, C. Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors in the failing heart: A growing potential. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2020, 34, 419–436.

- Aragon-Herrera, A.; Feijoo-Bandin, S.; Otero Santiago, M.; Barral, L.; Campos-Toimil, M.; Gil-Longo, J.; Costa Pereira, T.M.; Garcia-Caballero, T.; Rodriguez-Segade, S.; Rodriguez, J.; et al. Empagliflozin reduces the levels of cd36 and cardiotoxic lipids while improving autophagy in the hearts of zucker diabetic fatty rats. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2019, 170, 113677.

- Inoue, M.K.; Matsunaga, Y.; Nakatsu, Y.; Yamamotoya, T.; Ueda, K.; Kushiyama, A.; Sakoda, H.; Fujishiro, M.; Ono, H.; Iwashita, M.; et al. Possible involvement of normalized pin1 expression level and ampk activation in the molecular mechanisms underlying renal protective effects of sglt2 inhibitors in mice. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2019, 11, 57.

- Mizuno, M.; Kuno, A.; Yano, T.; Miki, T.; Oshima, H.; Sato, T.; Nakata, K.; Kimura, Y.; Tanno, M.; Miura, T. Empagliflozin normalizes the size and number of mitochondria and prevents reduction in mitochondrial size after myocardial infarction in diabetic hearts. Physiol. Rep. 2018, 6, e13741.

- Zhou, H.; Wang, S.; Zhu, P.; Hu, S.; Chen, Y.; Ren, J. Empagliflozin rescues diabetic myocardial microvascular injury via ampk-mediated inhibition of mitochondrial fission. Redox Biol. 2018, 15, 335–346.

- Packer, M. Activation and inhibition of sodium-hydrogen exchanger is a mechanism that links the pathophysiology and treatment of diabetes mellitus with that of heart failure. Circulation 2017, 136, 1548–1559.

- Gui, L.; Liu, B.; Lv, G. Hypoxia induces autophagy in cardiomyocytes via a hypoxia-inducible factor 1-dependent mechanism. Exp. Ther. Med. 2016, 11, 2233–2239.

- Salim, H.M.; Fukuda, D.; Yagi, S.; Soeki, T.; Shimabukuro, M.; Sata, M. Glycemic control with ipragliflozin, a novel selective sglt2 inhibitor, ameliorated endothelial dysfunction in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mouse. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2016, 3, 43.

- Habibi, J.; Aroor, A.R.; Sowers, J.R.; Jia, G.; Hayden, M.R.; Garro, M.; Barron, B.; Mayoux, E.; Rector, R.S.; Whaley-Connell, A.; et al. Sodium glucose transporter 2 (sglt2) inhibition with empagliflozin improves cardiac diastolic function in a female rodent model of diabetes. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2017, 16, 9.

- Andreadou, I.; Efentakis, P.; Balafas, E.; Togliatto, G.; Davos, C.H.; Varela, A.; Dimitriou, C.A.; Nikolaou, P.E.; Maratou, E.; Lambadiari, V.; et al. Empagliflozin limits myocardial infarction in vivo and cell death in vitro: Role of stat3, mitochondria, and redox aspects. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 1077.

- Nojima, T.; Matsubayashi, Y.; Yoshida, A.; Suganami, H.; Abe, T.; Ishizawa, M.; Fujihara, K.; Tanaka, S.; Kaku, K.; Sone, H. Influence of an sglt2 inhibitor, tofogliflozin, on the resting heart rate in relation to adipose tissue insulin resistance. Diabet. Med. 2020, 37, 1316–1325.

- Falcao-Pires, I.; Leite-Moreira, A.F. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: Understanding the molecular and cellular basis to progress in diagnosis and treatment. Heart Fail. Rev. 2012, 17, 325–344.

- O’Meara, E.; McDonald, M.; Chan, M.; Ducharme, A.; Ezekowitz, J.A.; Giannetti, N.; Grzeslo, A.; Heckman, G.A.; Howlett, J.G.; Koshman, S.L.; et al. Ccs/chfs heart failure guidelines: Clinical trial update on functional mitral regurgitation, sglt2 inhibitors, arni in hfpef, and tafamidis in amyloidosis. Can. J. Cardiol. 2020, 36, 159–169.

- Santos-Gallego, C.G.; Garcia-Ropero, A.; Mancini, D.; Pinney, S.P.; Contreras, J.P.; Fergus, I.; Abascal, V.; Moreno, P.; Atallah-Lajam, F.; Tamler, R.; et al. Rationale and design of the empa-tropism trial (atru-4): Are the “cardiac benefits” of empagliflozin independent of its hypoglycemic activity? Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2019, 33, 87–95.

More

Information

Subjects:

Medicine, Research & Experimental

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.7K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

18 Apr 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No