| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pietro Molinaro | -- | 1772 | 2022-04-01 10:37:33 | | | |

| 2 | Bruce Ren | + 1 word(s) | 1773 | 2022-04-02 03:44:22 | | |

Video Upload Options

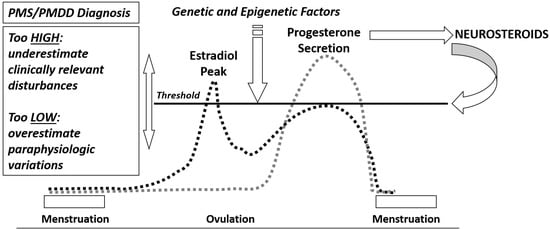

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) encompass a variety of symptoms that occur during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle and impair daily life activities and relationships. Depending on the type and severity of physical, emotional or behavioral symptoms, women of reproductive age followed for at least two prospective menstrual cycles may receive one of the two diagnoses. PMDD is the most severe form of PMS, predominantly characterized by emotional and behavioral symptoms not due to another psychiatric disorder. PMS and PMDD are common neuro-hormonal gynecological disorders with a multifaceted etiology. Gonadal steroid hormones and their metabolites influence a plethora of biological systems involved in the occurrence of specific symptoms, but there is no doubt that PMS/PMDD are centrally based disorders. A more sensitive neuroendocrine threshold to cyclical variations of estrogens and progesterone under physiological and hormonal therapies is present. Moreover, altered brain sensitivity to allopregnanolone, a metabolite of progesterone produced after ovulation potentiating GABA activity, along with an impairment of opioid and serotoninergic systems, may justify the occurrence of emotional and behavioral symptoms. Even neuro-inflammation expressed via the GABAergic system is under investigation as an etiological factor of PMS/PMDD.

1. Introduction

2. Epidemiology and Risks Factors of PMS/PMDD

3. Neuroendocrine Aspects of PMS/PMDD

Estrogens and Progesterone

References

- Critchley, H.O.; Babayev, E.; Bulun, S.E.; Clark, S.; Garcia-Grau, I.; Gregersen, P.K.; Kilcoyne, A.; Kim, J.-Y.J.; Lavender, M.; Marsh, E.E.; et al. Menstruation: Science and society. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 223, 624–664.

- Roeder, H.J.; Leira, E.C. Effects of the Menstrual Cycle on Neurological Disorders. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2021, 21, 34.

- Pinkerton, J.V.; Guico-Pabia, C.J.; Taylor, H.S. Menstrual cycle-related exacerbation of disease. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 202, 221–231.

- Barrington, D.J.; Robinson, H.J.; Wilson, E.; Hennegan, J. Experiences of menstruation in high income countries: A systematic review, qualitative evidence synthesis and comparison to low- and middle-income countries. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255001.

- Matteson, K.A.; Zaluski, K.M. Menstrual Health as a Part of Preventive Health Care. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 46, 441–453.

- Tassorelli, C.; Greco, R.; Allena, M.; Terreno, E.; Nappi, R.E. Transdermal Hormonal Therapy in Perimenstrual Migraine: Why, When and How? Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2012, 16, 467–473.

- Shulman, L.P. Gynecological Management of Premenstrual Symptoms. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2010, 14, 367–375.

- Ismaili, E.; Consensus Group of the International Society for Premenstrual Disorders; Walsh, S.; O’Brien, P.M.S.; Bäckström, T.; Brown, C.; Dennerstein, L.; Eriksson, E.; Freeman, E.W.; Ismail, K.M.K.; et al. Fourth consensus of the International Society for Premenstrual Disorders (ISPMD): Auditable standards for diagnosis and management of premenstrual disorder. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2016, 19, 953–958.

- Sattar, K. Epidemiology of Premenstrual Syndrome, A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2014, 8, 106–109.

- Yonkers, K.A.; Simoni, M.K. Premenstrual disorders. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 218, 68–74.

- Pilver, C.E.; Kasl, S.; Desai, R.; Levy, B.R. Health advantage for black women: Patterns in pre-menstrual dysphoric disorder. Psychol. Med. 2011, 41, 1741–1750.

- Rapkin, A.J.; Winer, S.A. Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: Quality of life and burden of illness. Expert Rev. Pharm. Outcomes Res. 2009, 9, 157–170.

- Gao, M.; Gao, D.; Sun, H.; Cheng, X.; An, L.; Qiao, M. Trends in Research Related to Premenstrual Syndrome and Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder From 1945 to 2018: A Bibliometric Analysis. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 596128.

- Potter, J.; Bouyer, J.; Trussell, J.; Moreau, C. Premenstrual Syndrome Prevalence and Fluctuation over Time: Results from a French Population-Based Survey. J. Women’s Health 2009, 18, 31–39.

- Sander, B.; Gordon, J.L. Premenstrual Mood Symptoms in the Perimenopause. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2021, 23, 73.

- de Wit, A.E.; de Vries, Y.A.; de Boer, M.K.; Scheper, C.; Fokkema, A.; Janssen, C.A.; Giltay, E.J.; Schoevers, R.A. Efficacy of combined oral contraceptives for depressive symptoms and overall symptomatology in premenstrual syndrome: Pairwise and network meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 225, 624–633.

- Choi, S.H.; Hamidovic, A. Association Between Smoking and Premenstrual Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 575526.

- Bertone-Johnson, E.R.; Hankinson, S.E.; Willett, W.C.; Johnson, S.R.; Manson, J.E. Adiposity and the Development of Premenstrual Syndrome. J. Women’s Health 2010, 19, 1955–1962.

- Fernández, M.D.M.; Saulyte, J.; Inskip, H.; Takkouche, B. Premenstrual syndrome and alcohol consumption: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019490.

- Pearce, E.; Jolly, K.; Jones, L.; Matthewman, G.; Zanganeh, M.; Daley, A. Exercise for premenstrual syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BJGP Open 2020, 4, 25.

- Perkonigg, A.; Yonkers, K.A.; Pfister, H.; Lieb, R.; Wittchen, H.-U. Risk Factors for Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder in a Community Sample of Young Women: The role of traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2004, 65, 1314–1322.

- Studd, J. Severe premenstrual syndrome and bipolar disorder: A tragic confusion. Menopause Int. 2012, 18, 82–86.

- Slyepchenko, A.; Minuzzi, L.; Frey, B.N. Comorbid Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder and Bipolar Disorder: A Review. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 719241.

- Pereira, D.; Pessoa, A.R.; Madeira, N.; Macedo, A.; Pereira, A.T. Association between premenstrual dysphoric disorder and perinatal depression: A systematic review. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2021, 25, 61–70.

- Osborn, E.; Brooks, J.; O’Brien, P.M.S.; Wittkowski, A. Suicidality in women with Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder: A systematic literature review. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2021, 24, 173–184.

- Nobles, C.J.; Thomas, J.J.; Valentine, S.E.; Gerber, M.; Ba, A.S.V.; Marques, L. Association of premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder with bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder in a nationally representative epidemiological sample. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2016, 49, 641–650.

- Nappi, R.E.; Nappi, G. Neuroendocrine aspects of migraine in women. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2012, 28, 37–41.

- Stute, P.; Bodmer, C.; Ehlert, U.; Eltbogen, R.; Ging, A.; Streuli, I.; Von Wolff, M. Interdisciplinary consensus on management of premenstrual disorders in Switzerland. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2017, 33, 342–348.

- Amital, D.; Herskovitz, C.; Fostick, L.; Silberman, A.; Doron, Y.; Zohar, J.; Itsekson, A.; Zolti, M.; Rubinow, A.; Amital, H. The Premenstrual Syndrome and Fibromyalgia—Similarities and Common Features. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2010, 38, 107–115.

- Graziottin, A. The shorter, the better: A review of the evidence for a shorter contraceptive hormone-free interval. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2016, 21, 93–105.

- Stahl, S.M. Estrogen Makes the Brain a Sex Organ. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1997, 58, 421–422.

- Backstrom, T.; Sanders, D.; Leask, R.; Davidson, D.; Warner, P.; Bancroft, J. Mood, Sexuality, Hormones, and the Menstrual Cycle. II. Hormone Levels and Their Relationship to the Premenstrual Syndrome. Psychosom. Med. 1983, 45, 503–507.

- Soares, C.N.; Zitek, B. Reproductive hormone sensitivity and risk for depression across the female life cycle: A continuum of vulnerability? J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2008, 33, 331–343.

- Wise, D.D.; Felker, A.; Stahl, S.M. Tailoring treatment of depression for women across the reproductive lifecycle: The importance of pregnancy, vasomotor symptoms, and other estrogen-related events in psychopharmacology. CNS Spectr. 2008, 13, 647–662.

- Genazzani, A.; Gastaldi, M.; Bidzinska, B.; Mercuri, N.; Nappi, R.; Segre, A.; Petraglia, F. The brain as a target organ of gonadal steroids. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1992, 17, 385–390.

- Bernardi, F.; Pluchino, N.; Stomati, M.; Pieri, M.; Genazzani, A.R. CNS: Sex Steroids and SERMs. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2003, 997, 378–388.

- Giatti, S.; Diviccaro, S.; Serafini, M.M.; Caruso, D.; Garcia-Segura, L.M.; Viviani, B.; Melcangi, R.C. Sex differences in steroid levels and steroidogenesis in the nervous system: Physiopathological role. Front. Neuroendocr. 2019, 56, 100804.

- Schweizer-Schubert, S.; Gordon, J.L.; Eisenlohr-Moul, T.A.; Meltzer-Brody, S.; Schmalenberger, K.M.; Slopien, R.; Zietlow, A.-L.; Ehlert, U.; Ditzen, B. Steroid Hormone Sensitivity in Reproductive Mood Disorders: On the Role of the GABAA Receptor Complex and Stress During Hormonal Transitions. Front. Med. 2021, 7, 479646.

- Yonkers, K.A.; O’Brien, P.S.; Eriksson, E. Premenstrual syndrome. Lancet 2008, 371, 1200–1210.

- McEvoy, K.; Osborne, L.; Nanavati, J.; Payne, J.L. Reproductive Affective Disorders: A Review of the Genetic Evidence for Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder and Postpartum Depression. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2017, 19, 94.

- Schmidt, P.J.; Nieman, L.K.; Danaceau, M.A.; Adams, L.F.; Rubinow, D.R. Differential Behavioral Effects of Gonadal Steroids in Women with and in Those without Premenstrual Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 338, 209–216.

- Studd, J.W. A guide to the treatment of depression in women by estrogens. Climacteric 2011, 14, 637–642.

- Bixo, M.; Johansson, M.; Timby, E.; Michalski, L.; Bäckström, T. Effects of GABA active steroids in the female brain with a focus on the premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J. Neuroendocr. 2018, 30, e12553.

- Yen, J.-Y.; Lin, H.-C.; Liu, T.-L.; Long, C.-Y.; Ko, C.-H. Early- and Late-Luteal-Phase Estrogen and Progesterone Levels of Women with Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4352.

- Bäckström, T.; Andreen, L.; Birzniece, V.; Björn, I.; Johansson, I.-M.; Nordenstam-Haghjo, M.; Nyberg, S.; Poromaa, I.S.; Wahlström, G.; Wang, M.; et al. The Role of Hormones and Hormonal Treatments in Premenstrual Syndrome. CNS Drugs 2003, 17, 325–342.

- Oinonen, K.A.; Mazmanian, D. To what extent do oral contraceptives influence mood and affect? J. Affect. Disord. 2002, 70, 229–240.

- Schmidt, P.J.; Rubinow, D.R. Sex Hormones and Mood in the Perimenopause. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009, 1179, 70–85.

- Chan, A.F.; Mortola, J.F.; Wood, S.H.; Yen, S.S. Persistence of premenstrual syndrome during low-dose administration of the pro-gesterone antagonist RU 486. Obstet. Gynecol. 1994, 84, 1001–1005.

- Schmidt, P.J.; Nieman, L.K.; Grover, G.N.; Muller, K.L.; Merriam, G.R.; Rubinow, D.R. Lack of Effect of Induced Menses on Symptoms in Women with Premenstrual Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991, 324, 1174–1179.

- Critchley, H.O.D.; Chodankar, R.R. 90 YEARS OF PROGESTERONE: Selective progesterone receptor modulators in gynaecological therapies. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2020, 65, T15–T33.

- Comasco, E.; Kallner, H.K.; Bixo, M.; Hirschberg, A.L.; Nyback, S.; de Grauw, H.; Epperson, C.N.; Sundström-Poromaa, I. Ulipristal Acetate for Treatment of Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder: A Proof-of-Concept Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Psychiatry 2021, 178, 256–265.

- Baller, E.B.; Wei, S.-M.; Kohn, P.D.; Rubinow, D.R.; Alarcón, G.; Schmidt, P.J.; Berman, K.F. Abnormalities of Dorsolateral Prefrontal Function in Women with Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder: A Multimodal Neuroimaging Study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2013, 170, 305–314.

- Wei, S.-M.; Baller, E.B.; Martinez, P.E.; Goff, A.C.; Li, H.J.; Kohn, P.D.; Kippenhan, J.S.; Soldin, S.J.; Rubinow, D.R.; Goldman, D.; et al. Subgenual cingulate resting regional cerebral blood flow in premenstrual dysphoric disorder: Differential regulation by ovarian steroids and preliminary evidence for an association with expression of ESC/E(Z) complex genes. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 206.

- Kaltsouni, E.; Fisher, P.M.; Dubol, M.; Hustad, S.; Lanzenberger, R.; Frokjaer, V.G.; Wikström, J.; Comasco, E.; Sundström-Poromaa, I. Brain reactivity during aggressive response in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder treated with a selective progesterone receptor modulator. Neuropsychopharmacology 2021, 46, 1460–1467.

- Wyatt, K.M.; Dimmock, P.W.; O’Brien, P.S.; Ismail, K.M.; Jones, P.W. The effectiveness of GnRHa with and without ‘add-back’ therapy in treating premenstrual syndrome: A meta analysis. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2004, 111, 585–593.

- Segebladh, B.; Borgström, A.; Nyberg, S.; Bixo, M.; Sundström-Poromaa, I. Evaluation of different add-back estradiol and progesterone treatments to gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist treatment in patients with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 201, 139.e1–139.e8.