| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Suryani Saallah | + 4137 word(s) | 4137 | 2022-03-08 06:48:46 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | Meta information modification | 4137 | 2022-03-09 10:22:53 | | |

Video Upload Options

Extensive research and development in the production of nanocellulose, a green, bio-based, and renewable biomaterial has paved the way for the development of advanced functional materials for a multitude of applications. From a membrane technology perspective, the exceptional mechanical strength, high crystallinity, tunable surface chemistry, and anti-fouling behavior of nanocellulose, manifested from its structural and nanodimensional properties are particularly attractive. Thus, an opportunity has emerged to exploit these features to develop nanocellulose-based membranes for environmental applications including water filtration, environmental remediation, and for the development of pollutant sensors and energy devices.

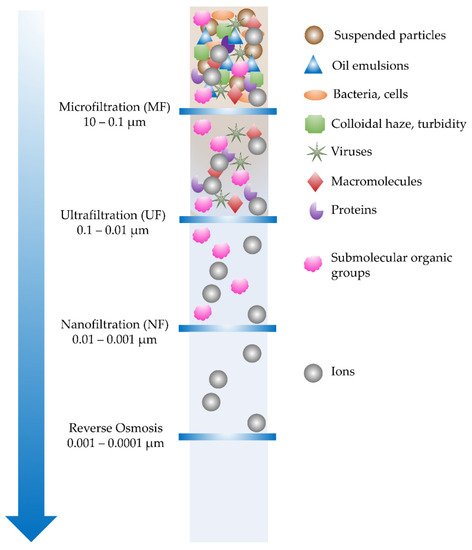

1. Water Filtration

2. Environmental Remediation

2.1. Nanocellulose as Adsorbent

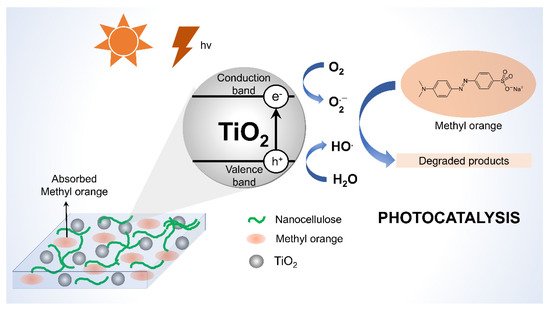

2.2. Nanocellulose as Photocatalyst

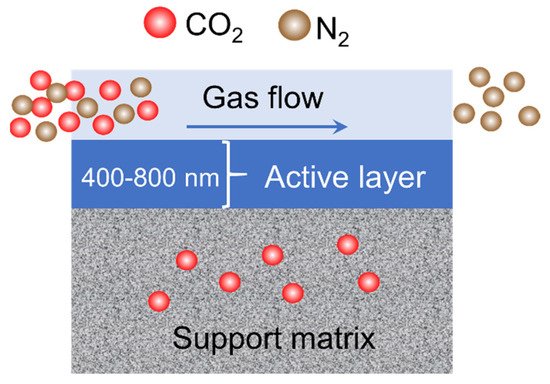

2.3. Nanocellulose for Gas Separation

3. Pollutant Sensors

4. Energy Devices

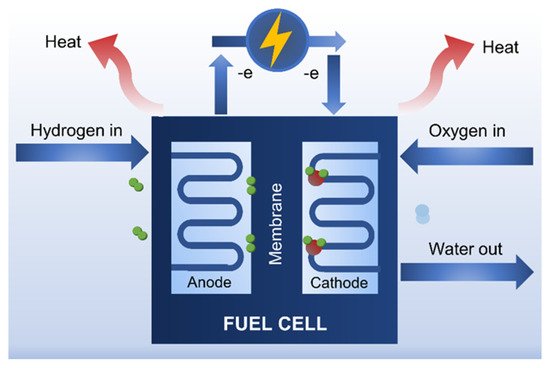

4.1. Fuel Cells

4.2. Solar Cells

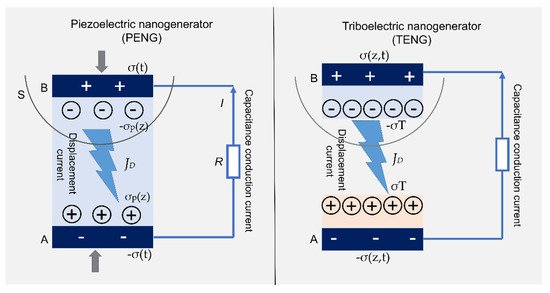

4.3. Nanogenerators

References

- Tan, H.-F.; Ooi, B.; Leo, C. Future perspectives of nanocellulose-based membrane for water treatment. J. Water Process. Eng. 2020, 37, 101502.

- Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Shen, Z. Nanocellulose based filtration membrane in industrial waste water treatment: A review. Materials 2021, 14, 5398.

- Reshmy, R.; Thomas, D.; Philip, E.; Paul, S.A.; Madhavan, A.; Sindhu, R.; Binod, P.; Pugazhendhi, A.; Sirohi, R.; Tarafdar, A.; et al. Potential of nanocellulose for wastewater treatment. Chemosphere 2021, 281, 130738.

- Sharma, P.R.; Sharma, S.K.; Lindström, T.; Hsiao, B.S. Nanocellulose-enabled membranes for water purification: Perspectives. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2020, 4, 1900114.

- Mautner, A. Nanocellulose water treatment membranes and filters: A review. Polym. Int. 2020, 69, 741–751.

- Varanasi, S.; Low, Z.-X.; Batchelor, W. Cellulose nanofibre composite membranes—Biodegradable and recyclable UF membranes. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 265, 138–146.

- Sijabat, E.K.; Nuruddin, A.; Aditiawati, P.; Purwasasmita, B.S. Synthesis and Characterization of Bacterial Nanocellulose from Banana Peel for Water Filtration Membrane Application. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1230, 012085.

- Kargarzadeh, H.; Ioelovich, M.; Ahmad, I.; Thomas, S.; Dufresne, A. Methods for extraction of nanocellulose from various sources. In Handbook of Nanocellulose and Cellulose Nanocomposites; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–49.

- Haafiz, M.M.; Hassan, A.; Khalil, H.A.; Khan, I.; Inuwa, I.; Islam, S.; Hossain, S.; Syakir, M.; Fazita, M.N. Bionanocomposite based on cellulose nanowhisker from oil palm biomass-filled poly(lactic acid). Polym. Test. 2015, 48, 133–139.

- Mokhena, T.C.; Mochane, M.J.; Mtibe, A.; John, M.J.; Sadiku, E.R.; Sefadi, J.S. Electrospun Alginate Nanofibers Toward Various Applications: A Review. Materials 2020, 13, 934.

- Cruz-Tato, P.; Ortiz-Quiles, E.O.; Vega-Figueroa, K.; Santiago-Martoral, L.; Flynn, M.; Díaz-Vázquez, L.M.; Nicolau, E. Metalized Nanocellulose Composites as a Feasible Material for Membrane Supports: Design and Applications for Water Treatment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 4585–4595.

- Goswami, R.; Mishra, A.; Bhatt, N.; Mishra, A.; Naithani, P. Potential of chitosan/nanocellulose based composite membrane for the removal of heavy metal (chromium ion). Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 46, 10954–10959.

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Yu, J.; Zhang, L.; Liu, L.; Zhou, X.; Huang, C.; Fan, Y. Preparation of nanocellulose/filter paper (NC/FP) composite membranes for high-performance filtration. Cellulose 2019, 26, 1183–1194.

- Vetrivel, S.; Saraswathi, M.S.S.A.; Rana, D.; Divya, K.; Nagendran, A. Cellulose acetate ultrafiltration membranes customized with copper oxide nanoparticles for efficient separation with antifouling behavior. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2021, 138.

- Kong, L.; Zhang, D.; Shao, Z.; Han, B.; Lv, Y.; Gao, K.; Peng, X. Superior effect of TEMPO-oxidized cellulose nanofibrils (TOCNs) on the performance of cellulose triacetate (CTA) ultrafiltration membrane. Desalination 2014, 332, 117–125.

- Aguilar-Sanchez, A.; Jalvo, B.; Mautner, A.; Nameer, S.; Pöhler, T.; Tammelin, T.; Mathew, A.P. Waterborne nanocellulose coatings for improving the antifouling and antibacterial properties of polyethersulfone membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 620, 118842.

- Tshikovhi, A.; Mishra, S.B.; Mishra, A.K. Nanocellulose-based composites for the removal of contaminants from wastewater. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 152, 616–632.

- Pagliaro, M.; Ciriminna, R.; Yusuf, M. Application of nanocellulose composites in the environmental engineering as a catalyst, flocculants, and energy storages: A review. J. Compos. Compd. 2021, 3, 114–128.

- Qiao, A.; Cui, M.; Huang, R.; Ding, G.; Qi, W.; He, Z.; Klemes, J.J.; Su, R. Advances in nanocellulose-based materials as adsorbents of heavy metals and dyes. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 272, 118471.

- Marakana, P.G.; Dey, A.; Saini, B. Isolation of nanocellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: Synthesis, characterization, modification, and potential applications. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106606.

- Reshmy, R.; Philip, E.; Madhavan, A.; Pugazhendhi, A.; Sindhu, R.; Sirohi, R.; Awasthi, M.K.; Pandey, A.; Binod, P. Nanocellulose as green material for remediation of hazardous heavy metal contaminants. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127516.

- Sun, H.; Guo, Y.; Zelekew, O.A.; Abdeta, A.B.; Kuo, D.-H.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, Z.; Lin, J.; Chen, X. Biological renewable nanocellulose templated CeO2/TiO2 synthesis and its photocatalytic removal efficiency of pollutants. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 336, 116873.

- Mutar, H.R.; Jasim, K.K. Adsorption study of disperse yellow dye on nanocellulose surface. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 1–7.

- Nematollahi, R.; Ziyadi, H.; Ghasemi, E.; Taheri, H. Cinnamon nanocellulose as a novel catalyst to remove methyl orange from aqueous solution. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2022, 137, 109222.

- Wu, J.; Dong, Z.; Li, X.; Li, P.; Wei, J.; Hu, M.; Geng, L.; Peng, X. Constructing Acid-Resistant Chitosan/Cellulose Nanofibrils Composite Membrane for the Adsorption of Methylene Blue. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4020850 (accessed on 30 January 2022).

- Lebogang, L.; Bosigo, R.; Lefatshe, K.; Muiva, C. Ag3PO4/nanocellulose composite for effective sunlight driven photodegradation of organic dyes in wastewater. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2019, 236, 121756.

- Voisin, H.; Falourd, X.; Rivard, C.; Capron, I. Versatile nanocellulose-anatase TiO2 hybrid nanoparticles in Pickering emulsions for the photocatalytic degradation of organic and aqueous dyes. JCIS Open 2021, 3, 100014.

- Liu, G.-Q.; Pan, X.-J.; Li, J.; Li, C.; Ji, C.-L. Facile preparation and characterization of anatase TiO2/nanocellulose composite for photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2021, 25, 101383.

- Nahi, J.; Radhakrishnan, A.; Beena, B. Green synthesis of zinc oxide incorporated nanocellulose with visible light photocatalytic activity and application for the removal of antibiotic enrofloxacin from aqueousmedia. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 41, 583–589.

- Jahan, Z.; Niazi, M.B.; Hagg, M.-B.; Gregersen, W. Decoupling the effect of membrane thickness and CNC concentration in PVA based nanocomposite membranes for CO2/CH4 separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 204, 220–225.

- Torstensen, J.; Helberg, R.M.; Deng, L.; Gregersen, W.; Syverud, K. PVA/nanocellulose nanocomposite membranes for CO2 separation from flue gas. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2019, 81, 93–102.

- Helberg, R.M.L.; Torstensen, J.O.; Dai, Z.; Janakiram, S.; Chinga-Carrasco, G.; Gregersen, O.W.; Syverud, K.; Deng, L. Nanocomposite membranes with high-charge and size-screened phosphorylated nanocellulose fibrils for CO2 separation. Green Energy Environ. 2021, 6, 585–596.

- Dai, L.; Wang, Y.; Zou, X.; Chen, Z.; Liu, H.; Ni, Y. Ultrasensitive Physical, Bio, and Chemical Sensors Derived from 1-, 2-, and 3-D Nanocellulosic Materials. Small 2020, 16, e1906567.

- Taheri, M.; Ahour, F.; Keshipour, S. Sensitive and selective determination of Cu 2+ at d -penicillamine functionalized nano-cellulose modified pencil graphite electrode. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2018, 117, 180–187.

- Shahi, N.; Lee, E.; Min, B.; Kim, D.-J. Rice Husk-Derived Cellulose Nanofibers: A Potential Sensor for Water-Soluble Gases. Sensors 2021, 21, 4415.

- Pouzesh, M.; Nekouei, S.; Zadeh, M.A.F.; Keshtpour, F.; Wang, S.; Nekouei, F. Fabrication of stable copper nanoparticles embedded in nanocellulose film as a bionanocomposite plasmonic sensor and thereof for optical sensing of cyanide ion in water samples. Cellulose 2019, 26, 4945–4956.

- Riva, L.; Fiorati, A.; Sganappa, A.; Melone, L.; Punta, C.; Cametti, M. Naked-Eye Heterogeneous Sensing of Fluoride Ions by Co-Polymeric Nanosponge Systems Comprising Aromatic-Imide-Functionalized Nanocellulose and Branched Polyethyleneimine. ChemPlusChem 2019, 84, 1512–1518.

- Weishaupt, R.; Siqueira, G.; Schubert, M.; Kämpf, M.M.; Zimmermann, T.; Maniura, K.; Faccio, G. A Protein-Nanocellulose Paper for Sensing Copper Ions at the Nano- to Micromolar Level. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1604291.

- Copur, F.; Bekar, N.; Zor, E.; Alpaydin, S.; Bingol, H. Nanopaper-based photoluminescent enantioselective sensing of L-Lysine by L-Cysteine modified carbon quantum dots. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 279, 305–312.

- Zor, E. Silver nanoparticles-embedded nanopaper as a colorimetric chiral sensing platform. Talanta 2018, 184, 149–155.

- Wang, W.; Zhang, T.-J.; Zhang, D.; Li, H.-Y.; Ma, Y.; Qi, L.; Zhou, Y.-L.; Zhang, X.-X. Amperometric hydrogen peroxide biosensor based on the immobilization of heme proteins on gold nanoparticles–bacteria cellulose nanofibers nanocomposite. Talanta 2011, 84, 71–77.

- Zhang, T.; Wang, W.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, X.; Ma, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Qi, L. Biotemplated Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticle-Bacteria Cellulose Nanofiber Nanocomposites and Their Application in Biosensing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2010, 20, 1152–1160.

- Park, M.; Chang, H.; Jeong, D.H.; Hyun, J. Spatial deformation of nanocellulose hydrogel enhances SERS. BioChip J. 2013, 7, 234–241.

- Tafete, G.A.; Abera, M.K.; Thothadri, G. Review on nanocellulose-based materials for supercapacitors applications. J. Energy Storage 2022, 48, 103938.

- Calle-Gil, R.; Castillo-Martínez, E.; Carretero-González, J. Cellulose Nanocrystals in Sustainable Energy Systems. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2022, 2100395.

- Rogalsky, S.; Bardeau, J.-F.; Makhno, S.; Babkina, N.; Tarasyuk, O.; Cherniavska, T.; Orlovska, I.; Kozyrovska, N.; Brovko, O. New proton conducting membrane based on bacterial cellulose/polyaniline nanocomposite film impregnated with guanidinium-based ionic liquid. Polymer 2018, 142, 183–195.

- Sriruangrungkamol, A.; Chonkaew, W. Modification of nanocellulose membrane by impregnation method with sulfosuccinic acid for direct methanol fuel cell applications. Polym. Bull. 2021, 78, 3705–3728.

- Muhmed, S.; Jaafar, J.; Daud, S.; Hanifah, M.F.R.; Purwanto, M.; Othman, M.; Rahman, M.; Ismail, A. Improvement in properties of nanocrystalline cellulose/poly (vinylidene fluoride) nanocomposite membrane for direct methanol fuel cell application. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105577.

- Ni, C.; Wei, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, B.; Sun, Z.; Gu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Hu, W. Novel proton exchange membranes based on structure-optimized poly(ether ether ketone ketone)s and nanocrystalline cellulose. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 434, 163–175.

- Aguas, H.; Mateus, T.; Vicente, A.; Gaspar, D.; Mendes, M.J.; Schmidt, W.A.; Pereira, L.; Fortunato, E.; Martins, R. Thin Film Silicon Photovoltaic Cells on Paper for Flexible Indoor Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015, 25, 3592–3598.

- Nogi, M.; Karakawa, M.; Komoda, N.; Yagyu, H.; Nge, T.T. Transparent Conductive Nanofiber Paper for Foldable Solar Cells. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17254.

- Jia, C.; Li, T.; Chen, C.; Dai, J.; Kierzewski, I.M.; Song, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, C.; Wang, C.; Hu, L. Scalable, anisotropic transparent paper directly from wood for light management in solar cells. Nano Energy 2017, 36, 366–373.

- Voggu, V.R.; Sham, J.; Pfeffer, S.; Pate, J.; Fillip, L.; Harvey, T.B.; Brown, J.R.M.; Korgel, B.A. Flexible CuInSe2 Nanocrystal Solar Cells on Paper. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 2, 574–581.

- Zhao, Y.; Liao, Q.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, Q.; Liao, X.; Zhang, Y. High output piezoelectric nanocomposite generators composed of oriented BaTiO3 Nano Energy 2015, 11, 719–727.

- Yao, C.; Hernandez, A.; Yu, Y.Y.; Cai, Z.; Wang, X. Triboelectric nanogenerators and power-boards from cellulose nanofibrils and recycled materials. Nano Energy 2016, 30, 103–108.

- Yao, C.; Yin, X.; Yu, Y.; Cai, Z.; Wang, X. Chemically Functionalized Natural Cellulose Materials for Effective Triboelectric Nanogenerator Development. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 794.

- Kim, H.-J.; Yim, E.-C.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, S.-J.; Park, J.-Y.; Oh, I. Bacterial Nano-Cellulose Triboelectric Nanogenerator. Nano Energy 2017, 33, 130–137.

- Bayer, T.; Cunning, B.; Selyanchyn, R.; Nishihara, M.; Fujikawa, S.; Sasaki, K.; Lyth, S.M. High Temperature Proton Conduction in Nanocellulose Membranes: Paper Fuel Cells. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 4805–4814.

- Ram, F.; Velayutham, P.; Sahu, A.K.; Lele, A.K.; Shanmuganathan, K. Enhancing thermomechanical and chemical stability of polymer electrolyte membranes using polydopamine coated nanocellulose. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2020, 3, 1988–1999.

- Hambardzumyan, A.; Vayer, M.; Foulon, L.; Pernes, M.; Devers, T.; Bigarré, J.; Aguie-Beghin, V. Nafion membranes reinforced by cellulose nanocrystals for fuel cell applications: Aspect ratio and heat treatment effects on physical properties. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 4684–4703.

- Ni, C.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, B.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, M.; Hu, W.; Liang, L. Crosslinking effect in nanocrystalline cellulose reinforced sulfonated poly (aryl ether ketone) proton exchange membranes. Solid State Ion. 2018, 323, 5–15.

- Etuk, S.S.; Lawan, I.; Zhou, W.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wei, X.; Zhang, M.; Fernando, G.F.; Yuan, Z. Synthesis and characterization of triazole based sulfonated nanocrystalline cellulose proton conductor. Cellulose 2020, 27, 3197–3209.

- Hubler, A.; Trnovec, B.; Zillger, T.; Ali, M.; Wetzold, N.; Mingebach, M.; Wagenpfahl, A.; Deibel, C.; Dyakonov, V. Printed Paper Photovoltaic Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2011, 1, 1018–1022.

- Shahnaz, T.; Bedadeep, D.; Narayanasamy, S. Investigation of the adsorptive removal of methylene blue using modified nanocellulose. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 200, 162–171.

- Helmiyati, H.; Fitriana, N.; Chaerani, M.L.; Dini, F.W. Green hybrid photocatalyst containing cellulose and γ–Fe2O3–ZrO2 heterojunction for improved visible-light driven degradation of Congo red. Opt. Mater. 2022, 124, 111982.

- Guo, C.; Zhou, L.; Lv, J. Effects of expandable graphite and modified ammonium polyphosphate on the flame-retardant and mechanical properties of wood flour-polypropylene composites. Polym. Polym. Compos. 2013, 21, 449–456.

- Brunetti, F.; Operamolla, A.; Castro-Hermosa, S.; Lucarelli, G.; Manca, V.; Farinola, G.M.; Brown, T.M. Printed Solar Cells and Energy Storage Devices on Paper Substrates. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29.

- Gao, L.; Chao, L.; Hou, M.; Liang, J.; Chen, Y.; Yu, H.-D.; Huang, W. Flexible, transparent nanocellulose paper-based perovskite solar cells. npj. Flex. Electron. 2019, 3, 4.

- Zhang, F.; Li, Y.; Cai, H.; Liu, Q.; Tong, G. Processing nanocellulose foam into high-performance membranes for harvesting energy from nature. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 241, 116253.

- Wang, X.; Yao, C.; Wang, F.; Li, Z. Cellulose-Based Nanomaterials for Energy Applications. Small 2017, 13, 1702240.