Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adriany Amorim | + 2434 word(s) | 2434 | 2022-02-15 09:03:58 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 2434 | 2022-02-24 03:49:21 | | | | |

| 3 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 2434 | 2022-02-24 09:02:13 | | | | |

| 4 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 2434 | 2022-02-28 01:58:13 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Amorim, A. Various Uses of Lycopene. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19819 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Amorim A. Various Uses of Lycopene. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19819. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Amorim, Adriany. "Various Uses of Lycopene" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19819 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Amorim, A. (2022, February 23). Various Uses of Lycopene. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19819

Amorim, Adriany. "Various Uses of Lycopene." Encyclopedia. Web. 23 February, 2022.

Copy Citation

Lycopene is a carotenoid abundantly found in red vegetables. This natural pigment displays an important role in human biological systems due to its excellent antioxidant and health-supporting functions, which show a protective effect against cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, cancers, and diabetes.

lycopene

carotenoids

isomers

antioxidants

cancers

food technology

pharmaceuticals

cosmetics

biotechnology

1. Lycopene Bio-availability

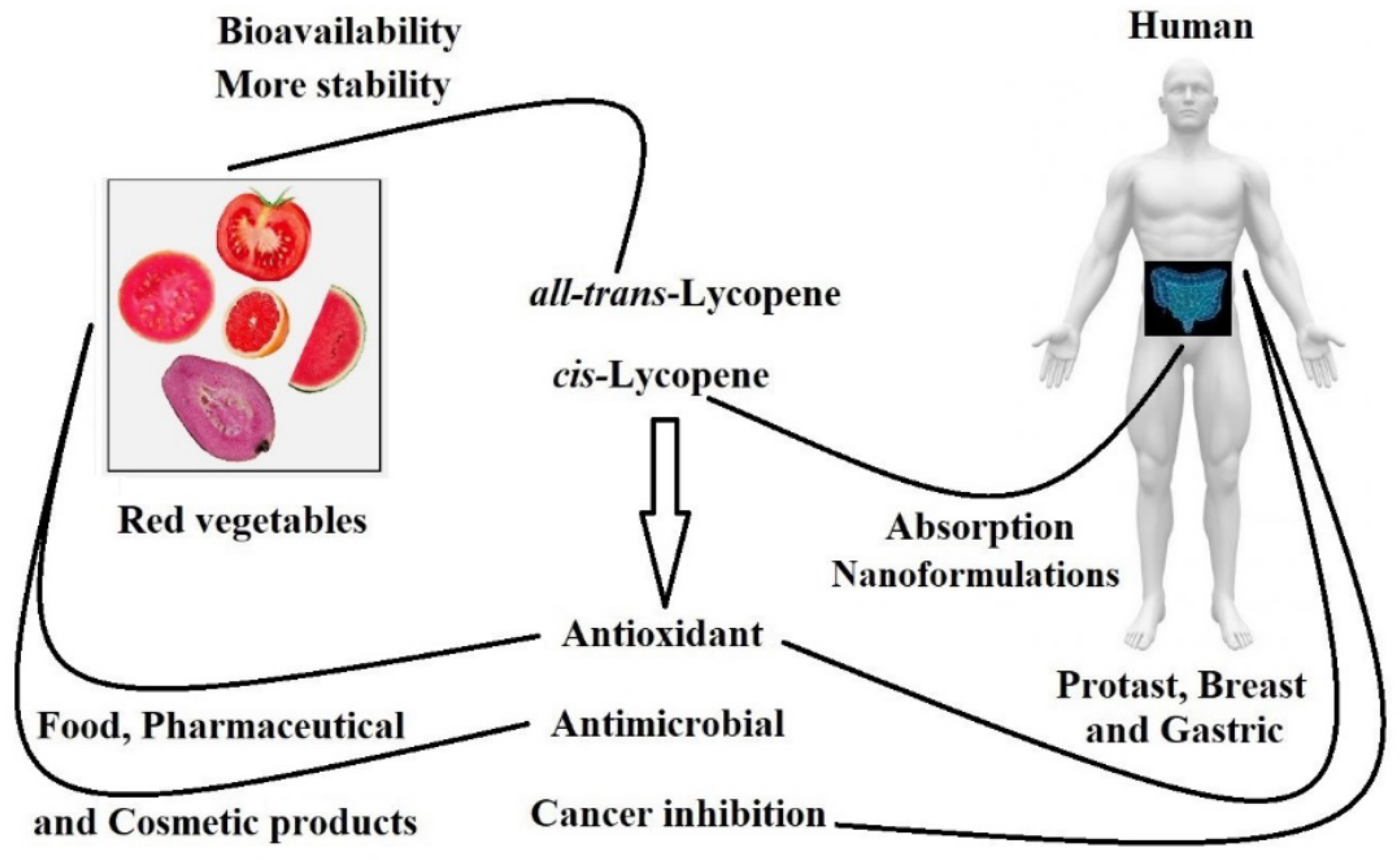

Lycopene is a carotenoid abundantly found in red vegetables (Figure 1). This natural pigment displays an important role in human biological systems due to its excellent antioxidant and health-supporting functions, which show a protective effect against cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, cancers, and diabetes [1][2].

Figure 1. Representation of bio-availability and functions of lycopene in humans as well as products from foods, pharmaceutical and cosmetic products.

Furthermore, studies have shown the potential anticancer activity of lycopene, suggesting that its consumption may prevent prostate, esophagus, stomach, colorectal, pancreas, breast, and cervix cancers. However, the literature has not determined the cause–effect relationship and how the consumption of lycopene-rich food decreases cancer risk [3][4][5][6].

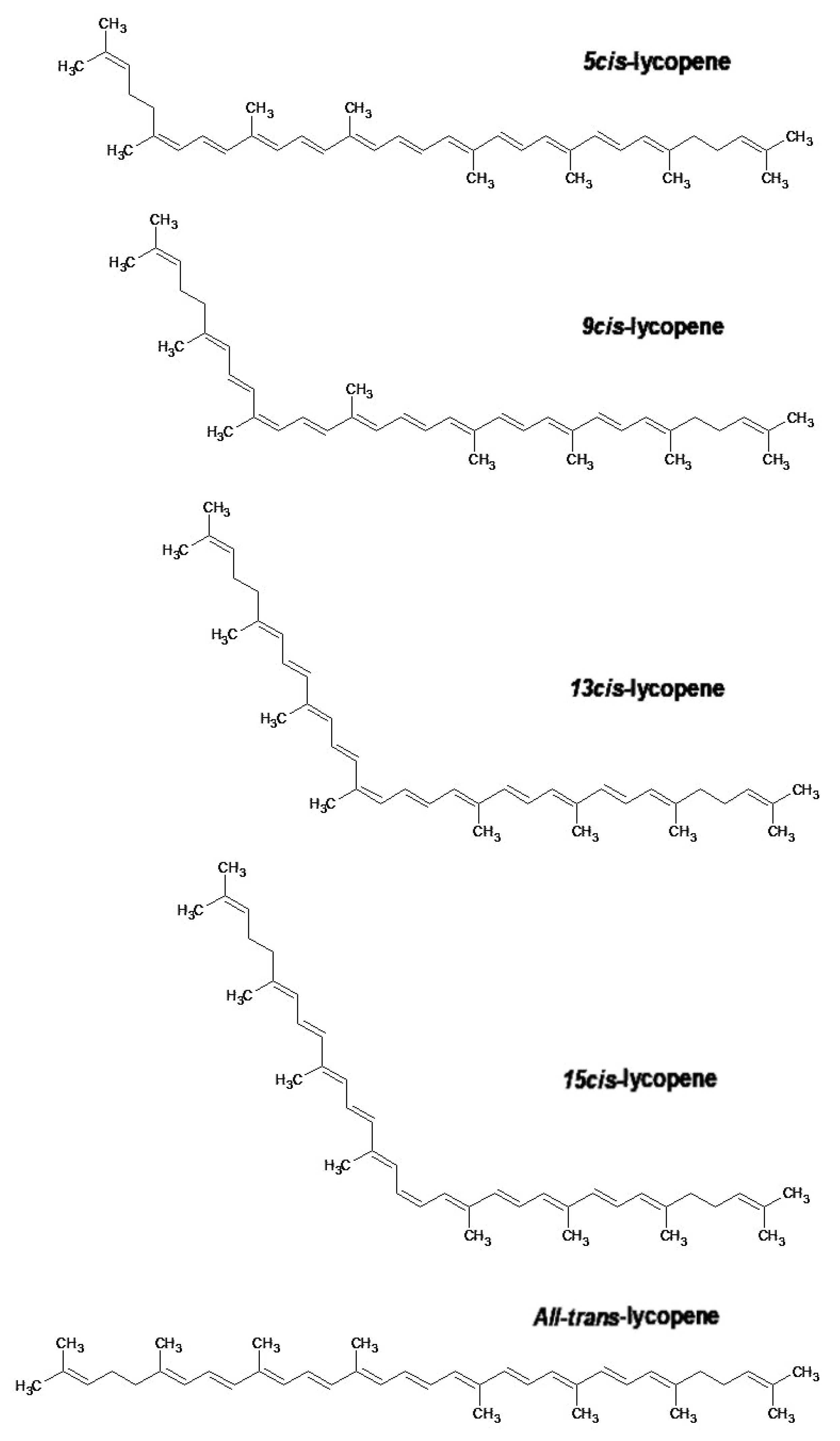

Lycopene is an organic molecule whose molecular formula is C40H56 and molecular weight is 536.85 g·mol−1. It is insoluble in water but soluble in some organic solvents [7][8]. Its molecular structure contains 13 double bonds, 11 of which are conjugated and provide characteristics for lycopene’s antioxidant activity and strong red color [7][9].

These double bonds are affected by the action of oxidants, and can be damaged by light, acid, and heat, which destroy or rearrange the structure of lycopene to different spatial cis configurations from all-trans-isomers [10]. These effects may deteriorate and/or lead to the loss of lycopene bioactivity [5][10]. The latter seems to depend on several factors, including lycopene content, the complex composition of food, and particle size consumed in the digestive process [4].

All-trans-lycopene (Figure 2) is interesting for industrial use in food and pharmaceuticals because of its high stability compared to other isomers of lycopene. All-trans-lycopene presents higher color intensity than cis isomers due to its low extinction coefficient. In nature, the trans-lycopene configuration has better stability compared with the cis isomer [3]. Nevertheless, the industry has also demonstrated interest in cis-lycopene structures (Figure 2) because they seem to have better bio-availability when compared to the all-trans isomer and can also prevent breast and prostate cancer [11][12][13].

The nutritional efficacy and industrial applicability of lycopene is limited due to its insolubility in water. On the other hand, nano-emulsified or micro-encapsulated lycopene, as well as lycopene nanoparticles, have demonstrated great in vitro bio-accessibility throughout the liberation of lycopene content from the nanostructure [3][11][16][17]. Therefore, micro- or nano-encapsulated lycopene may both overcome and avoid the problems related to lycopene structure and can present opportunities for the use of this potent antioxidant.

2. Production and Extraction Process

Several processes for the production and extraction of carotenoids such as lycopene have been proposed (Table 1). The most used method for extraction is solvent extraction and supercritical fluid extraction—SFE (supercritical CO2) [3][18][19]—and for production the most used is biosynthesis in a reactor or flask fermentation using biological strains, such as bacteria and yeasts [1][8][20][21]. Regardless of the method used, the lycopene extracts obtained have a red color, and their color intensity depends on lycopene concentration in the extraction media [22].

Table 1. Type of lycopene obtained from different extraction methods and biosynthesis from 2017 to 2021.

| Technique | Solvent/Mobile Phase/Flow Rate | Device | Temperature/ Pressure/Time/ V/Hz/rpm |

Lycopene Source/ Carotenoid Extracted |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extraction | Hexane | Soxhlet extractor | 37 °C/6 h | Tomato peel and seed/ cis and trans-lycopene |

[19] |

| * SC-CO2/1 mL·min−1 | SFT 110 extractor | 40 and 80 °C/30 and 50 MPa/30, 45, 60, 90, 120, 180, 240 min | |||

| Hexane/Acetone/Ethanol (2:1:1) | Vortex | 2 h | |||

| Washed in 0.1 M NaCl | Tomato peel and seed/ Lycopene and β-carotene |

[22] | |||

| OH pre-treatment | 55 °C/1 min | ||||

| Water/Ethanol (70%) (1:6 w/v) & |

Thermal extraction | 55 °C/15 min | |||

| Water/Ethanol (1:6 w/v) & + OH solution | |||||

| OH application | Ohmic heating (OH) technology (6–11 V·cm−1) pre-treatment |

0–100 °C/30 min/ 60–280 V/ 25 kHz |

|||

| * SC-CO2/1 L·min−1 | SFT 110 extractor | 60 °C and 40 MPa/ 30, 45, 60, 90, 120, 180, 240 min |

Tomato peel and seed/ Highest cis-lycopene content |

[23] | |

| Hexane | Soxhlet extractor/0.22 µm hydrophobic PTFE | 12 h | Tomato peel and seed/ Lycopene |

[24] | |

| Olive oil | Maceration (15 to 150 min)/Magnetic stirrer/Box–Behnken | 40–80 °C/ 200–400 rpm |

|||

| Methanol/Ethyl acetate/ Petroleum ether (1:1:1, v/v/v) |

Tomato peel and seed from 10 varieties/ Lycopene, β-carotene, and lutein |

[25] | |||

| 30% Methanolic potassium hydroxide | Room temperature /6 h |

||||

| Saturated saline solution/ Diethyl ether/ Distilled water |

Washed | ||||

| Dry over anhydrous sodium sulfate |

Rotary evaporator R-124 |

35 °C | |||

| PEF (pre-treatment)1,3; 5 kV·cm−1/0.012 kJ·kg−1, 0.160 kJ·kg−1, 0.475 kJ·kg−1/10 Hz/20 μs | 20 ± 2 °C | Tomato peels/ cis and all trans-lycopene |

[26] | ||

| Acetone (1:40 w/v) & | Extraction flask | 25 °C/0–24 h /160 rpm |

|||

| Ethyl lactate (1:40 w/v) & | |||||

| Ethyl acetate | Thermal extraction | 75 °C/1 or 2 h | Plum tomato peels/ cis and all trans-lycopene |

[27] | |

| Ultrasounds | Approximately 0 °C/30 min | ||||

| Magnesium carbonate (20%) (sample/solution 1:1) | Orbital shaker | 25 °C/2 h | Tomato peels/ Lycopene |

[3] | |

| n-hexane/Acetone (3:1) | Ultrasonic | 50 °C/30 min (10 times) | |||

| Centrifuge | 10 °C/10 min | ||||

| Reduced volume | 40 °C/Low pressure | ||||

| Technique | Substrate | Device | Biological Strain | Carotenoid Produced | References |

| Biosynthesis | Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) as inducer |

Shaking flask (37 °C and 200 rpm) |

E. coli | Lycopene | [20] |

| Glucose | Shake flask (30 °C, 300–600 rpm) |

S. cerevisiae | Lycopene | [21] | |

| Glucose + Glycerol | Shake flask (37 °C, pH = 7.2, 48 h) |

Escherichia coli R122 |

Lycopene | [1] | |

| Glucose | |||||

| Oleic acid | Bioreactor (37 °C, pH = 7.2, 48 h) |

Escherichia coli FA03-PM |

|||

| Glucose | |||||

| Glucose + oleic acid + yeast extract | |||||

| Glucose + waste cooking oil + yeast extract | |||||

| Lactic acid | Flask fermentation (120 h) |

B. trispora NRRL 2895 (+) and N6 (−) |

Lycopene and β-carotene |

[8] |

* SC-CO2 = Supercritical Carbon Dioxide; (w/v) & = sample weight/solvent volume.

High temperatures (above 80 °C), light, oxygen, and exposure time may degrade lycopene, while the type of solvent can increase the isomerization from all-trans-lycopene to cis-lycopene. Acetone, for example, is one of the best solvents for extracting lycopene from fresh material once it provides better solubilization of the lipophilic intracellular content [26].

The use of electric processes to extract carotenoids from food has been successfully applied, with the advantage of promoting a selective extraction and improving carotenoid bio-availability [22]. Although the effects of electric processes on carotenoids are still unknown, applying low voltages could reduce the risk of damage to their structures [26]. These results have ushered in new studies about the factors that influence degradation, as well as “green” methods of lycopene recovery.

Supercritical CO2 is a technique that significantly impacts lycopene extraction, as it is considered an environmentally friendly method when compared with those that use solvents and lower temperatures [1][18][19][26]. The bacteria and yeasts introduced into bioreactors and the species Escherichia coli, Blakeslea trispora, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae stood out for lycopene production [8][20][21]. These microorganisms consume glucose, lactic acid, and fatty acids as nutrients at a temperature of around 30 °C, producing β-carotene and lycopene as final products [1][21].

Therefore, biosynthesis methods followed by ultrasound or enzymatic lysis to damage the cell membrane before supercritical fluid extraction could be an alternative to obtaining lycopene using a clean methodology.

It is noteworthy that the extraction methods applied in obtaining lycopene from red guava are patented methodologies and, for this reason, these methods are not mentioned in Table 1.

3. Lycopene Bio-accessibility and Bio-availability—Novel Technologies

Carotenoids can offer numerous health benefits when consumed consistently (Table 2). Nevertheless, for this purpose, there must be a first release from the food matrix followed by carotenoid diffusion into oil droplets. The bile salts help to create micelles to assist the digestion of lipid forms, converting them in free fatty acids, mono- and diacylglycerides, lysophospholipids, and free cholesterol [28]. The harsh conditions throughout the absorption and assimilation process might conduct lycopene degradation due to exposure to pH changes, increased temperature, and oxidation [29]. Consequently, bio-availability and absorption are much lower than water-soluble molecules [30].

Table 2. Recent examples of methods used to encapsulate lycopene from 2017 to 2021.

| Delivery System | Encapsulation Method | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-cyclodextrins | A mixture of methylene chloride solution of lycopene with ethanol at 37 °C. | Higher stability against oxidizing agents (AAPH and H2O2). | [31] |

| β-cyclodextrins | Lycopene inclusion complexes with β-cyclodextrin were prepared by the precipitation method. |

Increased thermal stability, photostability, and antioxidant activity. | [32] |

| Nanoliposomes | Sonication of lycopene, soybean phosphatidylcholine, cholesterol, and aqueous solution. |

Neuronal protection against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion. Improved therapeutic efficacy and attenuated the cardiotoxicity of the chemotherapy drug doxorubicin. |

[33] |

| Phospholipid nanoliposomes | Nanospheres of phospholipids with lycopene produced by evaporation and nanoliposomes produced by sonication with the presence of buffer and recovered by centrifugation. |

Enhanced antioxidant activity. Prevented reactive oxygen species-induced kidney tissue damage. |

[34] |

| Double-loaded liposomes |

Lycopene, β-cyclodextrins encapsulated with soy lecithin and cholesterol. | Prolonged-release. Improvement of lycopene solubility. Cardioprotective activity tested in vivo. |

[35] |

| Oil-in-water nano-emulsions |

Octenyl succinate anhydride-modified starch mixed with lycopene using high-pressure homogenization and medium-chain triglycerides as carrier oils. | Stable nano-emulsions system with potential application for functional foods. |

[2] |

| Oil-in-water emulsions |

Emulsion of water, pure whey isolate, citric acid, triglycerides, and lycopene created with pressure homogenizer. | Increased lycopene bio-accessibility. System critical for the delivery of lipophilic bioactive compounds in functional drinks. |

[36] |

| Nanodispersions | Homogenization of lycopene dissolved in dichloromethane, aqueous phase, and Tween 20. |

Small-size lycopene nanodispersions. Good stability for application in beverage products. |

[37] |

| Feed emulsions | Homogenization of tomato powders, maltodextrin, and gum Arabic in aqueous solution and encapsulation made by spray-drying. |

Increased lycopene stability. | [38] |

| Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) |

Lycopene-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles using Precirol® ATO 5, Compritol® 888 ATO, and myristic acid by hot homogenization. |

Stable after 2 months in an aqueous medium (4 °C). |

[39] |

| Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) |

Cold homogenization technique with glyceryl monostearate and lycopene. | Gel with a promising antioxidant therapy in periodontal defects. | [40] |

| Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) |

Homogenization-evaporation technique of lycopene-loaded SLN with different ratios of biocompatible Compritol® 888 ATO and gelucire. |

Particles showed in vitro anticancer activity. |

[41] |

| Nanostructure lipid carriers (NLCs) | Ultrasonication of lycopene with Tween 80 and Poloxamer 188. |

Enhanced oral bio-availability. Increased cytotoxicity against human breast tumor cells. |

[42] |

| Nanostructure lipid carriers (NLCs) | Homogenization and ultrasonication method (aqueous phase with Tween 80, lecithin, and lycopene). | Increased lycopene aqueous solubility. Improved solubility masking tomato aftertaste. Increased homogeneity of fortified orange drink. |

[43] |

| Nanostructure lipid carriers (NLCs) | Emulsion created with lycopene, a lipid mixture, Tween 80 followed by pressure homogenization. | Biphasic release pattern with fast release initially and a slower afterward. | [6] |

| Whey protein isolate nanoparticles | Lycopene loaded whey protein isolate nanoparticles. |

Enhance the oral bio-availability of lycopene. Controlled release. Facilitated absorption through the lymphatic pathway. |

[17] |

| Gelatin nanofibers | A mixture of gelatin from bovine skin and tomato extract is used in electrospinning. | Better retention of lycopene. Better antioxidant activity during 14-days storage. |

[44] |

| Ionic gelation | Lycopene watermelon concentrate mixed with sodium alginate or pectin. Encapsulation by dipping in CaCl2 and drying under vacuum. |

More stable lycopene-rich beads. Good application as natural colorants/antioxidants in different types of food products. |

[45] |

| Nano-encapsulation | CPCs (Chlorella pyrenoidosa cells) loaded with lycopene into a complex nutraceutical and exogenous. |

Feasibility of lycopene encapsulation in the CPCs. Combined the activities of both materials. Novel nutraceuticals to reduce cellular oxidative stress. |

[10] |

| Nano-emulsion | Lycopene from guava on nanoemulsifying system of natural oils. | Lycopene nano-emulsion with high stability. Significant inhibition of edema formation, suggesting a potential candidate for anti-inflammatory therapy. |

[16] |

| Lipid-core Nanocapsules | Nano-encapsulation process mixed lycopene extract from guava with polycaprolactone polymer in acetone sorbitan monostearate. | The nanostructure was cytotoxic against cancer cells (human breast adenocarcinoma line MCF-7). | [12] |

| Nanoparticle | Polymer nanoparticle fucan-coated based on acetylated cashew gum and lycopene extract from guava. | Promising results for applicability in hydrophobic compounds carrying systems as lycopene with cytotoxic effect on the breast cancer cell. | [11] |

| Microencapsulation | Microencapsulation of lycopene from tomato peels by complex coacervation and freeze-drying. |

The fine orange-yellow powder could be micro-encapsulated as stable lycopene applied to the food industry with properties against metabolic syndrome. |

[3] |

Strategies have been created to control problems related to the practical application of lycopene, which is strongly restricted due to its high sensitivity when exposed to light, oxygen, and heat, as well as contact with metal ions, besides processing conditions and low water solubility [11][46].

Encapsulation is one of the techniques that frequently uses oligosaccharides, such as cyclodextrins, to associate compounds in a hydrophobic core, while on the outside it forms a hydrophilic shell. The encapsulation protects lycopene from degradation and isomerization besides increasing its solubility in aqueous environments [46]. A report on the lycopene/α- and β-CD complexes pointed that both could provide stable associations in water with profound differences in structure [47]. Maltodextrins were used during tomato processing to powders aiming to increase lycopene stability [48].

Respective delivery systems have been created to enhance lycopene bio-availability and absorption rates (Figure 1) in the gastrointestinal environment [37][49]. During digestion, carotenoids are assimilated with other lipids into mixed micelles containing bile salts and phospholipids, which perform as carriers to solubilize the carotenoids and transport them to the zone of maximum absorption in the intestine. Incorporating lycopene into the oil phase of emulsions is an alternative to protect it from oxidation and chemical degradation, providing better bio-availability and prolonging shelf-life [28]. Nano-emulsions have been reported to be suitable delivery systems with favorable results for the encapsulation of low-solubility compounds, such as lycopene [46]. Recent works have shown efficient delivery systems for lycopene: its incorporation in oil-in-water emulsions for orange beverages [50], lycopene encapsulated in isolate-Xylo-oligosaccharide protein conjugates made by Maillard reaction [49], and oil-in-water emulsions with long- to short-chain triglycerides [37]. The literature also reports the formation of liposomes and nanoliposomes, which are spherical vesicles created with a concentric phospholipid bilayer of hydrophilic center. It was reported that lycopene tends to be entrapped in the hydrophobic bilayer, enhancing bio-accessibility when exposed to the gastrointestinal tract and with increased antioxidant capacity compared with the free form [51][52].

Oil–water nano-emulsions are nanoparticles dispersed in heterogeneous systems with an inner lipidic and an external aqueous phase stabilized by one or two surfactants. Unlike the nano-emulsions, lipid nanoparticles have an internal solid lipid phase since these nanoparticles are totally or mainly composed of solid lipids at room temperature. Such a solid matrix allows the controlled release of the encapsulated molecules and protects them from degradation while increasing the long-term stability of the system [53]. Lycopene-loaded SLNs demonstrated stability in an aqueous medium for two months, producing an applicable system for future in vivo trials in nutraceutical industries [39]. The encapsulation in SLN showed an improvement in lycopene oral delivery, and an ex vivo assessment determined that this carotenoid had better permeation besides causing more cytotoxicity against breast cancer cells [42]. Lycopene loaded into nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC) composed of Eumulgin SG, orange wax, and rice bran oil, employing high pressure in homogenization process, showed chemical stability and delayed degradation when put into cold storage [54].

Moreover, lycopene nano-emulsions have provided more thermal stability for lycopene and significantly inhibited edema formation. For this reason, these nanoparticles may be considered to be a potential candidate for anti-inflammatory therapy [16]. Lipid-core nanocapsules of lycopene, in turn, optimized stability for 7 months at 5 °C storage, and improved its toxicity against breast cancer cells. The nanocapsules also inhibited the production of intracellular peroxyl radicals in human microglial cells and maintained the membrane integrity of erythrocytes, highlighting its potential to be employed in cancer treatment [12].

Lycopene encapsulated in polymeric nanoparticles showed high anti-tumor potential, with cytotoxicity against cancer cells at low concentrations and no toxicity against Galleria mellonella. Additionally, nanoparticles with sizes of 162.10 ± 3.21 nm were efficient with a passive mechanism of permeability for targeting tumor tissues [11].

On the other hand, lycopene powder produced by complex coacervation and freeze-drying after microencapsulation had promising results as a biopolymeric composite with inhibitory effect potential on α-amylase associated with metabolic syndrome, and demonstrated high antioxidant activity in formulations [3].

References

- Liu, N.; Liu, B.; Wang, G.; Soong, Y.-H.V.; Tao, Y.; Liu, W.; Xie, D. Lycopene production from glucose, fatty acid, and waste cooking oil by metabolically engineered Escherichia Coli. Biochem. Eng. J. 2020, 155, 107488.

- Li, D.; Li, L.; Xiao, N.; Li, M.; Xie, X. Physical properties of oil-in-water nanoemulsions stabilized by OSA-modified starch for the encapsulation of lycopene. Colloids Surf. A 2018, 552, 59–66.

- Gheonea, I.; Aprodu, I.; Cîrciumaru, A.; Râpeanu, G.; Bahrim, G.E.; Stănciuc, N. Microencapsulation of lycopene from tomatoes peel by complex coacervation and freeze-drying: Evidence on phytochemical profile, stability, and food applications. J. Food Eng. 2021, 288, 110166.

- Nieva-Echevarría, B.; Goicoechea, E.; Guillén, M.D. Oxidative stability of extra-virgin olive oil-enriched or not with lycopene. Importance of the initial quality of the oil for its performance during in vitro gastrointestinal digestion. Food Res. Int. 2020, 130, 108987.

- Liang, X.; Ma, C.; Yan, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, F. Advances in research on bioactivity, metabolism, stability, and delivery systems of lycopene. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 93, 185–196.

- Yang, C.; Liu, H.; Sund, Q.; Xiong, W.; Yu, J.; Zhang, L. Enriched Z-isomers of lycopene-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers: Physicochemical characterization and in vitro bioaccessibility assessment using a diffusion model. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 111, 767–773.

- Mirahmadi, M.; Azimi-Hashemi, S.; Saburi, E.; Kamalie, H.; Pishbin, M.; Hadizadeh, F. Potential inhibitory effect of lycopene on prostate cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 129, 110459.

- Wang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Fu, J.; Yang, Q.; Feng, L. High-throughput screening of lycopene-overproducing mutants of Blakeslea trispora by combining ARTP mutation with microtiter plate cultivation and transcriptional changes revealed by RNA-seq. Biochem. Eng. J. 2020, 161, 107664.

- Li, W.; Yalcin, M.; Lin, Q.; Ardawi, M.-S.M.; Mousa, S.A. Self-assembly of green tea catechin derivatives in nanoparticles for oral lycopene delivery. J. Control. Release 2017, 248, 117–124.

- Pu, C.; Tang, W. Encapsulation of lycopene in Chlorella pyrenoidosa: Loading properties and stability improvement. Food Chem. 2017, 235, 283–289.

- Andrades, E.O.; Costa, J.M.A.R.; Neto, F.E.M.L.; Araujo, A.R.; Ribeiro, F.O.S.; Vasconcelos, A.G.; Oliveira, A.C.J.; Sobrinho, J.L.S.; Almeida, M.P.; Carvalho, A.P.; et al. Acetylated cashew gum and fucan for incorporation of lycopene rich extract from red guava (Psidium guajava L.) in nanostructured systems: Antioxidant and antitumor capacity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 191, 1026–1037.

- Vasconcelos, A.G.; Valim, M.O.; Amorim, A.G.N.; Amaral, C.P.; Almeida, M.P.; Borges, T.K.S.; Socodato, R.; Portugal, C.C.; Brand, G.D.; Mattos, J.S.C.; et al. Cytotoxic activity of poly-ɛ-caprolactone lipid-core nanocapsules loaded with lycopene-rich extract from red guava (Psidium guajava L.) on breast cancer cells. Food Res. Int. 2020, 136, 109548.

- Santos, R.C.; Ombredane, A.S.; Souza, J.M.T.; Vasconcelos, A.G.; Plácido, A.; Amorim, A.G.N.; Barbosa, E.A.; Lima, F.C.D.A.; Ropke, C.D.; Alves, M.M.M.; et al. Lycopene-rich extract from red guava (Psidium guajava L.) displays cytotoxic effect against human breast adenocarcinoma cell line MCF-7 via an apoptotic-like pathway. Food Res. Int. 2018, 105, 184–196.

- PubChem. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- ACD/Labs. Available online: https://www.acdlabs.com/solutions/academia (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Amorim, A.; Souza, J.; Oliveira, A.; Santos, R.; Vasconcelos, A.; Souza, L.; Araújo, T.; Cabral, W.; Silva, M.; Mafud, A.; et al. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity improvement of lycopene from guava on nanoemulsifying system. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2021, 42, 760–770.

- Jain, A.; Sharma, G.; Ghoshal, G.; Kesharwani, P.; Singh, B.; Shivhare, U.S.; Katare, O.P. Lycopene Loaded Whey Protein Isolate Nanoparticles: An Innovative Endeavor for Enhanced Bioavailability of Lycopene and Anti-Cancer Activity. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 546, 97–105.

- Šojić, B.; Pavlić, B.; Tomović, V.; Kocić-Tanackov, S.; Đurović, S.; Zeković, Z.; Belović, M.; Torbica, A.; Jokanović, M.; Uromović, N.; et al. Tomato pomace extract and organic peppermint essential oil as effective sodium nitrite replacement in cooked pork sausages. Food Chem. 2020, 330, 127202.

- Vallecilla-Yepez, L.; Ciftci, O.N. Increasing cis-lycopene content of the oleoresin from tomato processing by-products using supercritical carbon dioxide. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 95, 354–360.

- Cui, M.; Wang, Z.; Hu, X.; Wang, X. Effects of lipopolysaccharide structure on lycopene production in Escherichia coli. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2019, 124, 9–16.

- Ma, T.; Shi, B.; Ye, Z.; Li, X.; Liu, M.; Chen, Y.; Xia, J.; Nielsen, J.; Deng, Z.; Liu, T. Lipid engineering combined with systematic metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for high-yield production of lycopene. Metab. Eng. 2019, 52, 134–142.

- Coelho, M.; Pereira, R.; Rodrigues, A.S.; Teixeira, J.A.; Pintado, M.E. Extraction of tomato by-products’ bioactive compounds using ohmic technology. Food Bioprod. Process. 2019, 117, 329–339.

- Hatami, T.; Meireles, M.A.A.; Ciftci, O.N. Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of lycopene from tomato processing by-products: Mathematical modeling and optimization. J. Food Eng. 2019, 241, 18–25.

- Kehili, M.; Sayadi, S.; Frikha, F.; Zammel, A.; Allouche, N. Optimization of lycopene extraction from tomato peels industrial by-product using maceration in refined olive oil. Food Bioprod. Process. 2019, 117, 321–328.

- Szabo, K.; Dulf, F.V.; Diaconeasa, Z.; Vodnar, D.C. Antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of tomato processing byproducts and their correlation with the biochemical composition. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 116, 108558.

- Pataro, G.; Carullo, D.; Falcone, M.; Ferrari, G. Recovery of lycopene from industrially derived tomato processing byproducts by pulsed electric fields-assisted extraction. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 63, 102369.

- Martínez-Hernández, G.B.; Castillejo, N.; Artés-Hernández, F. Effect of fresh–cut apples fortification with lycopene microspheres, revalorized from tomato by-products, during shelf life. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2019, 156, 110925.

- Meroni, E.; Raikos, V. Lycopene in Beverage Emulsions: Optimizing Formulation Design and Processing Effects for Enhanced Delivery. Beverages 2018, 4, 14.

- Chacón-Ordóñez, T.; Carle, R.; Schweiggert, R. Bioaccessibility of Carotenoids from Plant and Animal Foods. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 3220–3239.

- García-Hernández, J.; Hernández-Pérez, M.; Peinado, I.; Andrés, A.; Heredia, A. Tomato-Antioxidants Enhance Viability of L. Reuteri under Gastrointestinal Conditions While the Probiotic Negatively Affects Bioaccessibility of Lycopene and Phenols. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 43, 1–7.

- Fernández-García, E.; Pérez-Gálvez, A. Carotenoid: β-Cyclodextrin Stability Is Independent of Pigment Structure. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 1317–1321.

- Wang, H.; Wang, S.; Zhu, H.; Wang, S.; Xing, J. Inclusion Complexes of Lycopene and β-Cyclodextrin: Preparation, Characterization, Stability and Antioxidant Activity. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 314.

- Zhao, Y.; Xin, Z.; Li, N.; Chang, S.; Chen, Y.; Geng, L.; Chang, H.; Shi, H.; Chang, Y.-Z. Nano-Liposomes of Lycopene Reduces Ischemic Brain Damage in Rodents by Regulating Iron Metabolism. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 124, 1–11.

- Stojiljkovic, N.; Ilic, S.; Jakovljevic, V.; Stojanovic, N.; Stojnev, S.; Kocic, H.; Stojanovic, M.; Kocic, G. The Encapsulation of Lycopene in Nanoliposomes Enhances Its Protective Potential in Methotrexate-Induced Kidney Injury Model. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2627917.

- Jhan, S.; Pethe, A.M. Double-Loaded Liposomes Encapsulating Lycopene β-Cyclodextrin Complexes: Preparation, Optimization, and Evaluation. J. Liposome Res. 2020, 30, 80–92.

- Raikos, V.; Hayward, N.; Hayes, H.; Meroni, E.; Ranawana, V. Optimising the Ratio of Long- to Short-Chain Triglycerides of the Lipid Phase to Enhance Physical Stability and Bioaccessibility of Lycopene-Loaded Beverage Emulsions. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 54, 1355–1362.

- Shariffa, Y.N.; Tan, T.B.; Uthumporn, U.; Abas, F.; Mirhosseini, H.; Nehdi, I.A.; Wang, Y.-H.; Tan, C.P. Producing a Lycopene Nanodispersion: Formulation Development and the Effects of High Pressure Homogenization. Food Res. Int. 2017, 101, 165–172.

- Montiel-Ventura, J.; Luna-Guevara, J.J.; Tornero-Campante, M.A.; Delgado-Alvarado, A.; Luna-Guevara, M.L. Study of Encapsulation Parameters to Improve Content of Lycopene in Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) Powders. Acta Aliment. 2018, 47, 135–142.

- Nazemiyeh, E.; Eskandani, M.; Sheikhloie, H.; Nazemiyeh, H. Formulation and Physicochemical Characterization of Lycopene-Loaded Solid Lipid Nanoparticles. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2016, 6, 235–241.

- Tawfik, M.S.; Abdel-Ghaffar, K.A.; Gamal, A.Y.; El-Demerdash, F.H.; Gad, H.A. Lycopene Solid Lipid Microparticles with Enhanced Effect on Gingival Crevicular Fluid Protein Carbonyl as a Biomarker of Oxidative Stress in Patients with Chronic Periodontitis. J. Liposome Res. 2019, 29, 375–382.

- Jain, A.; Sharma, G.; Kushwah, V.; Thakur, K.; Ghoshal, G.; Singh, B.; Jain, S.; Shivhare, U.S.; Katare, O.P. Fabrication and Functional Attributes of Lipidic Nanoconstructs of Lycopene: An Innovative Endeavour for Enhanced Cytotoxicity in MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cells. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2017, 152, 482–491.

- Singh, A.; Neupane, Y.R.; Panda, B.P.; Kohli, K. Lipid Based Nanoformulation of Lycopene Improves Oral Delivery: Formulation Optimization, Ex Vivo Assessment, and Its Efficacy against Breast Cancer. J. Microencapsul. 2017, 34, 416–429.

- Zardini, A.A.; Mohebbi, M.; Farhoosh, R.; Bolurian, S. Production and characterization of nanostructured lipid carriers and solid lipid nanoparticles containing lycopene for food fortification. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 287–298.

- Horuz, T.İ.; Belibağlı, K.B. Nanoencapsulation by electrospinning to improve stability and water solubility of carotenoids extracted from tomato peels. Food Chem. 2018, 268, 86–93.

- Sampaio, G.L.A.; Pacheco, S.; Ribeiro, A.P.O.; Galdeano, M.C.; Gomes, F.S.; Tonon, R.V. Encapsulation of a lycopene-rich watermelon concentrate in alginate and pectin beads: Characterization and stability. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 116, 108589.

- Focsan, A.L.; Polyakov, N.E.; Kispert, L.D. Supramolecular Carotenoid Complexes of Enhanced Solubility and Stability—The Way of Bioavailability Improvement. Molecules 2019, 24, 3947.

- Mele, A.; Mendichi, R.; Selva, A.; Molnar, P.; Toth, G. Non-Covalent Associations of Cyclomaltooligosaccharides (Cyclodextrins) with Carotenoids in Water. A Study on the α- and β-Cyclodextrin/ψ,ψ-Carotene (Lycopene) Systems by Light Scattering, Ionspray Ionization and Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Carbohydr. Res. 2002, 337, 1129–1136.

- Harsha, P.S.C.S.; Lavelli, V. Effects of Maltodextrins on the Kinetics of Lycopene and Chlorogenic Acid Degradation in Dried Tomato. Molecules 2019, 24, 6–1042.

- Jia, C.; Cao, D.; Ji, S.; Lin, W.; Zhang, X.; Muhoza, B. Whey Protein Isolate Conjugated with Xylo-Oligosaccharides via Maillard Reaction: Characterization, Antioxidant Capacity, and Application for Lycopene Microencapsulation. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 118, 108837.

- Meroni, E.; Raikos, V. Formulating Orange Oil-in-Water Beverage Emulsions for Effective Delivery of Bioactives: Improvements in Chemical Stability, Antioxidant Activity and Gastrointestinal Fate of Lycopene Using Carrier Oils. Food Res. Int. 2018, 106, 439–445.

- Tan, C.; Zhang, Y.; Abbas, S.; Feng, B.; Zhang, X.; Xia, S. Modulation of the Carotenoid Bioaccessibility through Liposomal Encapsulation. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2014, 123, 692–700.

- Tan, C.; Xue, J.; Abbas, S.; Feng, B.; Zhang, X.; Xia, S. Liposome as a Delivery System for Carotenoids: Comparative Antioxidant Activity of Carotenoids as Measured by Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power, DPPH Assay and Lipid Peroxidation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 6726–6735.

- Garcês, A.; Amaral, M.H.; Lobo, J.M.S.; Silva, A.C. Formulations Based on Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLN) and Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLC) for Cutaneous Use: A Review. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 112, 159–167.

- Okonogi, S.; Riangjanapatee, P. Physicochemical Characterization of Lycopene-Loaded Nanostructured Lipid Carrier Formulations for Topical Administration. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 478, 726–735.

More

Information

Subjects:

Food Science & Technology; Chemistry, Medicinal; Oncology

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

2.0K

Revisions:

4 times

(View History)

Update Date:

28 Feb 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No