| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Georgios Fevgas | + 5509 word(s) | 5509 | 2022-02-09 07:39:09 | | | |

| 2 | Georgios Fevgas | Meta information modification | 5509 | 2022-02-09 12:37:55 | | | | |

| 3 | Rita Xu | -1114 word(s) | 4395 | 2022-02-10 02:55:53 | | |

Video Upload Options

The coverage path planning (CPP) algorithms aim to cover the total area of interest with minimum overlapping. The goal of the CPP algorithms is to minimize the total covering path and execution time. Significant research has been done in robotics, particularly for multi-unmanned unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) cooperation and energy efficiency in CPP problems.

1. Introduction

2. No Decomposition

3. Exact Cellular Decomposition

4. Trapezoidal Decomposition

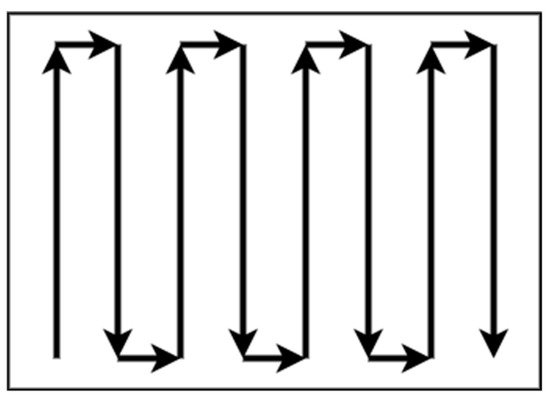

One exact cellular decomposition technique for irregular spaces that can give a complete coverage path is trapezoidal decomposition. This method is classified in the offline category of algorithms because it does not use remote-sensing information [31][32]. Each cell is a trapezoid in this method, and simple methods such as back and forth can be used to cover every cell. The coverage can be achieved by an exhaustive walk that generates a path to cover each cell to execute the path using back and forth motions such as boustrophedon, as shown in Figure 3. Often, this method is used for agriculture applications where the fields are polygonal and clear from obstacles. Oksanen and Visala [33] introduced an algorithm for CPP in agricultural fields and used the path cost function to optimize the final path.

5. Boustrophedon Decomposition

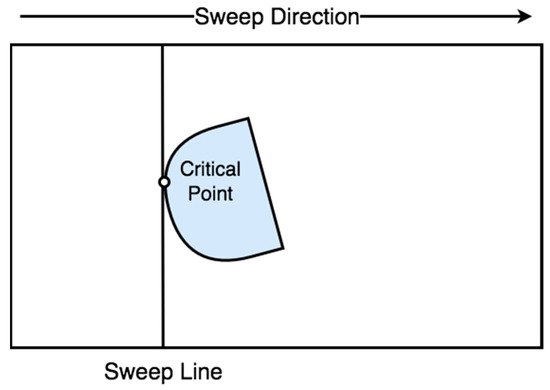

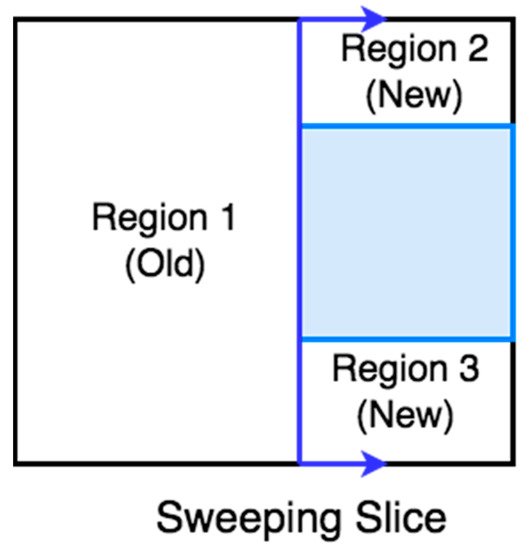

6. Morse-Based Decomposition

7. Online Topological Coverage Algorithm

8. Contact Sensor-Based Coverage of Rectilinear Environments

9. Grid-Based Methods

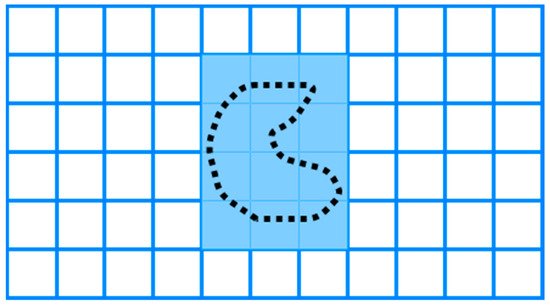

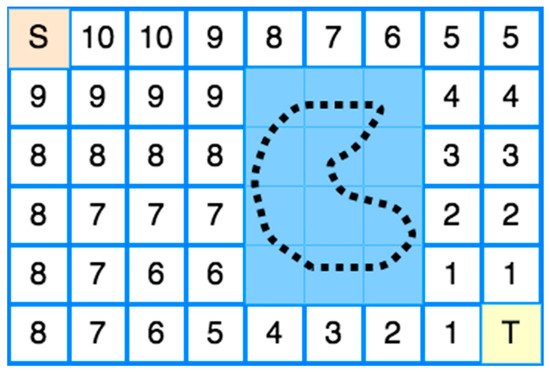

9.1. Wavefront Algorithm

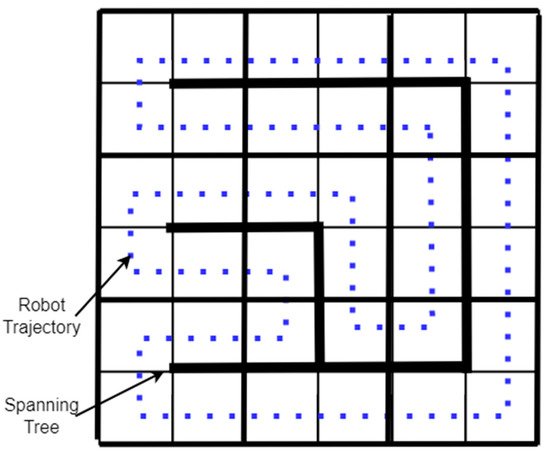

9.2. Spanning Tree Coverage

10. Neural Network-Based Coverage on Grid Maps

| CPP Approach | Decomposition Method | Algorithm Processing | Shape of Area | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boustrophedon | None | Offline | Rectangular | [25][26][27] |

| Square | None | Offline | Square | [28] |

| Boustrophedon, Spiral | Exact cellular | Offline | Polygon, Concave | [29] |

| Back and Forth | Trapezoidal | Offline | Polygon | [31][32] |

| Boustrophedon | Boustrophedon | Offline | Polygon | [25][27] |

| Boustrophedon | Morse-based | Online | Any dimensional | [34] |

| Online Topological | Slice | Online | Polygon | [38] |

| Contact Sensor-based | Exact cellular | Online | Rectilinear | [40] |

| Wavefront | Approximate cellular | Offline | Polygon, Concave | [42] |

| Wavefront | Approximate cellular | Online | Polygon, Concave | [43] |

| STC | Approximate cellular | Offline | Polygon, Concave | [29] |

| Spiral-STC | Approximate cellular | Online | Polygon, Concave | [44] |

| Neural Network-based | Approximate cellular | Online | Polygon, Concave | [45][46] |

11. Multi-Robot CPP Strategies

12. Multi-Robot Boustrophedon Decomposition

13. Multi-Robot Spanning Tree Coverage

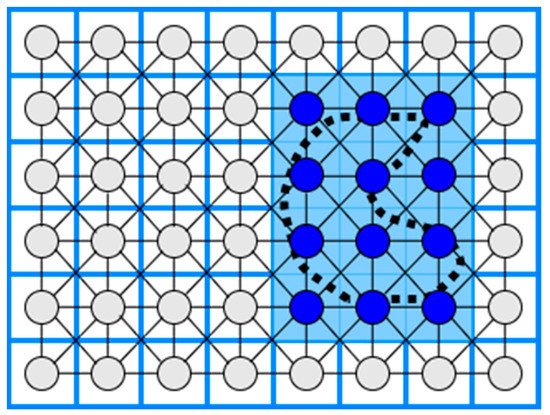

14. Multi-Robot Neural Network-Based Coverage

15. Multi-Robot Graph-Based and Boundary Coverage

16. Multi-UAV CPP Methods

17. Multi-UAV Coverage

18. Back-and-Forth

19. Spiral

20. Multi-Objective Path Planning (MOPP) with Genetic Algorithm (GA)

21. Genetic Algorithm (GA) with Flood Fill Algorithm

Table 3. Multi-UAV CPP strategies.

| CPP Approach | Type of UAVs | Algorithm Processing | Evaluation Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-perimeter method | Homogeneous | Online | Minimize latency | [55] |

| Back-and-Forth | Homogeneous | Online/Offline | Total path length Time coverage |

[23][58] |

| Back-and-Forth | Heterogeneous | Offline | Number of turns | [53] |

| Spiral | Heterogeneous | Offline | Coverage path, Number of turns | [59][60] |

| Multi-Objective Path Planning with GA | Homogeneous | Offline/Online | Mission Completion Time | [65] |

| GA with flood fill algorithm | Homogeneous | Offline/Online | Path length | [66][67] |

22. Energy-Saving CPP Algorithms

Table 4. CPP energy-aware methods.

| CPP Method | Energy-Saving Approach | Type of UAV | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy gain path | Energy exploitation of the wind | Fixed-wing | [68] |

| Back and Forth | Reducing the number of turns and the total flying path | Rotorcraft | [69] |

| Boustrophedon | The direction of the UAV path and the turns according to the wind direction | Fixed-wing | [70] |

| Back and Forth | Altitude maximization according to the Ground Sample Distance to reduce the number of turns | Rotorcraft | [18] |

| Spiral | Wider angle turns to minimize the acceleration and deceleration | Rotorcraft | [72] |

| Three stages energy optimal path | An energy-aware algorithm computes the take-off weight, flight speed, and air friction to generate an energy-optimal path | Rotorcraft | [74] |

| Smoothing turns | Smoothing the turns on a given path to minimize deceleration and acceleration before and after the turning point | Rotorcraft/Fixed-wing | [75] |

| Circular and straight lines with left turns paths | Cooperative coverage algorithm with critical time | Multiple Fixed-wing | [76] |

| Back and Forth | Minimizing the number of stripes and eventually the number of turns | Multiple Fixed-wing | [77] |

| Back and Forth | Reduce computational time, the number of turns, and path overlapping while minimizing the total coverage path | Rotorcraft | [78] |

| Back and Forth | Reducing the computational time and path length for the inter-regional path, the number of turning maneuvers, and path overlapping | Rotorcraft | [79] |

| ACO with Gaussian distribution functions | Path length, rotation angle, and area overlapping rate | Rotorcraft/Fixed-wing | [80] |

References

- Lagkas, T.; Argyriou, V.; Bibi, S.; Sarigiannidis, P. UAV IoT Framework Views and Challenges: Towards Protecting Drones as “Things”. Sensors 2018, 18, 4015.

- Azpúrua, H.; Freitas, G.M.; Macharet, D.G.; Campos, M.F.M. Multi-Robot Coverage Path Planning Using Hexagonal Segmentation for Geophysical Surveys. Robotica 2018, 36, 1144–1166.

- Maes, W.H.; Steppe, K. Perspectives for Remote Sensing with Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in Precision Agriculture. Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24, 152–164.

- Radoglou-Grammatikis, P.; Sarigiannidis, P.; Lagkas, T.; Moscholios, I. A Compilation of UAV Applications for Precision Agriculture. Comput. Netw. 2020, 172, 107148.

- Silvagni, M.; Tonoli, A.; Zenerino, E.; Chiaberge, M. Multipurpose UAV for Search and Rescue Operations in Mountain Avalanche Events. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2017, 8, 18–33.

- Yuan, C.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y. Aerial Images-Based Forest Fire Detection for Firefighting Using Optical Remote Sensing Techniques and Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2017, 88, 635–654.

- Straub, J. Unmanned Aerial Systems: Consideration of the Use of Force for Law Enforcement Applications. Technol. Soc. 2014, 39, 100–109.

- Deng, C.; Wang, S.; Huang, Z.; Tan, Z.; Liu, J. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles for Power Line Inspection: A Cooperative Way in Platforms and Communications. J. Commun. 2014, 9, 687–692.

- Cho, J.; Lim, G.; Biobaku, T.; Kim, S.; Parsaei, H. Safety and Security Management with Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) in Oil and Gas Industry. Procedia Manuf. 2015, 3, 1343–1349.

- Erdelj, M.; Natalizio, E. UAV-assisted disaster management: Applications and open issues. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Computing, Networking and Communications (ICNC), Kauai, HI, USA, 15–18 February 2016; pp. 1–5.

- Pliatsios, D.; Goudos, S.K.; Lagkas, T.; Argyriou, V.; Boulogeorgos, A.A.A.; Sarigiannidis, P. Drone-Base-Station for Next-Generation Internet-of-Things: A Comparison of Swarm Intelligence Approaches. IEEE Open J. Antennas Propag. 2021, 3, 32–47.

- Ballesteros, R.; Ortega, J.F.; Hernández, D.; Moreno, M.A. Applications of Georeferenced High-Resolution Images Obtained with Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Part I: Description of Image Acquisition and Processing. Precis. Agric. 2014, 15, 579–592.

- Barrientos, A.; Colorado, J.; del Cerro, J.; Martinez, A.; Rossi, C.; Sanz, D.; Valente, J. Aerial Remote Sensing in Agriculture: A Practical Approach to Area Coverage and Path Planning for Fleets of Mini Aerial Robots. J. Field Robot. 2011, 28, 667–689.

- Maza, I.; Capitán, J.; Merino, L.; Ollero, A. Multi-UAV cooperation. In Encyclopedia of Aerospace Engineering; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–10.

- Spyridis, Y.; Lagkas, T.; Sarigiannidis, P.; Zhang, J. Modelling and Simulation of a New Cooperative Algorithm for UAV Swarm Coordination in Mobile RF Target Tracking. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2021, 107, 102232.

- Rekleitis, I.; New, A.P.; Rankin, E.S.; Choset, H. Efficient Boustrophedon Multi-Robot Coverage: An Algorithmic Approach. Ann. Math. Artif. Intell. 2008, 52, 109–142.

- Nolan, P.; Paley, D.A.; Kroeger, K. Multi-UAS path planning for non-uniform data collection in precision agriculture. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 4–11 March 2017; pp. 1–12.

- Di Franco, C.; Buttazzo, G. Coverage Path Planning for UAVs Photogrammetry with Energy and Resolution Constraints. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2016, 83, 445–462.

- Choset, H. Coverage for Robotics—A Survey of Recent Results. Ann. Math. Artif. Intell. 2001, 31, 113–126.

- Galceran, E.; Carreras, M. A Survey on Coverage Path Planning for Robotics. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2013, 61, 1258–1276.

- Valente, J.; Del Cerro, J.; Barrientos, A.; Sanz, D. Aerial Coverage Optimization in Precision Agriculture Management: A Musical Harmony Inspired Approach. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2013, 99, 153–159.

- Paull, L.; Thibault, C.; Nagaty, A.; Seto, M.; Li, H. Sensor-Driven Area Coverage for an Autonomous Fixed-Wing Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2014, 44, 1605–1618.

- Xu, A.; Viriyasuthee, C.; Rekleitis, I. Optimal complete terrain coverage using an unmanned aerial vehicle. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Shanghai, China, 9–13 May 2011; pp. 2513–2519.

- Fazli, P.; Davoodi, A.; Mackworth, A.K. Multi-Robot Repeated Area Coverage. Auton. Robots 2013, 34, 251–276.

- Choset, H.; Pignon, P. Path Planning: The Boustrophedon Cellular Decomposition. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Field and Service Robotics, Canberra, Australia, 12 October 1997; pp. 1311–1320.

- Choset, H.; Pignon, P. Coverage path planning: The boustrophedon cellular decompositio. In Field and Service Robotics; Springer: London, UK, 1998; pp. 203–209.

- Choset, H.; Acar, E.; Rizzi, A.A.; Luntz, J. Exact cellular decompositions in terms of critical points of Morse functions. In Proceedings of the 2000 ICRA. Millennium Conference, IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Symposia Proceedings (Cat. No.00CH37065), San Francisco, CA, USA, 24–28 April 2000; Volume 3, pp. 2270–2277.

- Andersen, H.L. Path Planning for Search and Rescue Mission Using Multicopters. 2014. 135. Available online: https://ntnuopen.ntnu.no/ntnu-xmlui/handle/11250/261317 (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- LaValle, S.M. Planning Algorithms; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006.

- Zheng, X.; Jain, S.; Koenig, S.; Kempe, D. Multi-robot forest coverage. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2–6 August 2005; pp. 3852–3857.

- Choset, H.; Lynch, K.M.; Hutchinson, S.; Kantor, G.A.; Burgard, W. Principles of Robot Motion: Theory, Algorithms, and Implementations; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005.

- Latombe, J.-C. Robot Motion Planning; Stanford University, Kluwer Academic Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1991.

- Oksanen, T.; Visala, A. Coverage Path Planning Algorithms for Agricultural Field Machines. J. Field Robot. 2009, 26, 651–668.

- Acar, E.U.; Choset, H.; Rizzi, A.A.; Atkar, P.N.; Hull, D. Morse Decompositions for Coverage Tasks. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2002, 21, 331–344.

- SStein, E.; Milnor, J.W.; Spivak, M.; Wells, R.; Wells, R.; Mather, J.N. Morse Theory; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1963; ISBN 978-0-691-08008-6.

- Acar, E.U.; Choset, H.; Atkar, P.N. Complete sensor-based coverage with extended-range detectors: A hierarchical decomposition in terms of critical points and Voronoi diagrams. In Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Expanding the Societal Role of Robotics in the the Next Millennium (Cat. No.01CH37180), Maui, HI, USA, 29 October–3 November 2001; Volume 3, pp. 1305–1311.

- Acar, E.U.; Choset, H. Sensor-Based Coverage of Unknown Environments: Incremental Construction of Morse Decompositions. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2002, 21, 345–366.

- Wong, S. Qualitative Topological Coverage of Unknown Environments by Mobile Robots; The University of Auckland: Auckland, New Zealand, 2006.

- Wong, S.C.; MacDonald, B.A. Complete coverage by mobile robots using slice decomposition based on natural landmarks. In PRICAI 2004: Trends in Artificial Intelligence; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 683–692.

- Butler, Z.J.; Rizzi, A.A.; Hollis, R.L. Contact sensor-based coverage of rectilinear environments. In Proceedings of the 1999 IEEE International Symposium on Intelligent Control Intelligent Systems and Semiotics (Cat. No.99CH37014), Cambridge, MA, USA, 17 September 1999; pp. 266–271.

- Moravec, H.; Elfes, A. High resolution maps from wide angle sonar. In Proceedings of the 1985 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation Proceedings, St. Louis, MO, USA, 25–28 March 1985; Volume 2, pp. 116–121.

- Zelinsky, A.; Jarvis, R.A.; Byrne, J.C.; Yuta, S. Planning Paths of Complete Coverage of an Unstructured Environment by a Mobile Robot. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Robotics, Tsukuba, Japan, 11 September 1993; Volume 13, pp. 533–538.

- Shivashankar, V.; Jain, R.; Kuter, U.; Nau, D. Real-Time Planning for Covering an Initially-Unknown Spatial Environment. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Fourth International FLAIRS Conference, Palm Beach, FL, USA, 20 March 2011.

- Gabriely, Y.; Rimon, E. Spiral-STC: An on-Line Coverage Algorithm of Grid Environments by a Mobile Robot. In Proceedings of the 2002 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (Cat. No.02CH37292), Washington, DC, USA, 11–15 May 2002; Volume 1, pp. 954–960.

- Luo, C.; Yang, S.X.; Stacey, D.A.; Jofriet, J.C. A Solution to Vicinity Problem of Obstacles in Complete Coverage Path Planning. In Proceedings of the 2002 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (Cat. No.02CH37292), Washington, DC, USA, 11–15 May 2002; Volume 1, pp. 612–617.

- Yang, S.X.; Luo, C. A Neural Network Approach to Complete Coverage Path Planning. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part B Cybern. 2004, 34, 718–724.

- Hazon, N.; Mieli, F.; Kaminka, G.A. Towards Robust On-Line Multi-Robot Coverage. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, ICRA 2006, Orlando, FL, USA, 15–19 May 2006; pp. 1710–1715.

- Luo, C.; Yang, S.X. A real-time cooperative sweeping strategy for multiple cleaning robots. In Proceedings of the of the IEEE Internatinal Symposium on Intelligent Control, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 October 2002; pp. 660–665.

- Luo, C.; Yang, S.X.; Stacey, D.A. Real-time path planning with deadlock avoidance of multiple cleaning robots. In Proceedings of the 2003 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (Cat. No.03CH37422), Taipei, Taiwan, 14–19 September 2003; Volume 3, pp. 4080–4085.

- Easton, K.; Burdick, J. Inspection’. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Barcelona, Spain, 18–22 April 2005; pp. 727–734.

- Ju, C.; Son, H. Multiple UAV Systems for Agricultural Applications: Control, Implementation, and Evaluation. Electronics 2018, 7, 162.

- Vincent, P.; Rubin, I. A framework and analysis for cooperative search using UAV swarms. In Proceedings of the 2004 ACM symposium on Applied Computing, New York, NY, USA, 14 March 2004; pp. 79–86.

- Maza, I.; Ollero, A. Multiple UAV cooperative searching operation using polygon area decomposition and efficient coverage algorithms. In Distributed Autonomous Robotic Systems 6; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2007; pp. 221–230.

- Alotaibi, E.T.; Alqefari, S.S.; Koubaa, A. LSAR: Multi-UAV Collaboration for Search and Rescue Missions. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 55817–55832.

- Acevedo, J.J.; Arrue, B.C.; Maza, I.; Ollero, A. Cooperative Large Area Surveillance with a Team of Aerial Mobile Robots for Long Endurance Missions. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2013, 70, 329–345.

- Acevedo, J.J.; Arrue, B.C.; Maza, I.; Ollero, A. Distributed Approach for Coverage and Patrolling Missions with a Team of Heterogeneous Aerial Robots under Communication Constraints. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2013, 10, 28.

- Acevedo, J.J.; Arrue, B.C.; Diaz-Bañez, J.M.; Ventura, I.; Maza, I.; Ollero, A. One-to-One Coordination Algorithm for Decentralized Area Partition in Surveillance Missions with a Team of Aerial Robots. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2014, 74, 269–285.

- Xu, A.; Viriyasuthee, C.; Rekleitis, I. Efficient Complete Coverage of a Known Arbitrary Environment with Applications to Aerial Operations. Auton. Robots 2014, 36, 365–381.

- Balampanis, F.; Maza, I.; Ollero, A. Area Decomposition, Partition and Coverage with Multiple Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems Operating in Coastal Regions. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Arlington, VA, USA, 7–10 June 2016; pp. 275–283.

- Balampanis, F.; Maza, I.; Ollero, A. Coastal Areas Division and Coverage with Multiple UAVs for Remote Sensing. Sensors 2017, 17, 808.

- Kallmann, M.; Bieri, H.; Thalmann, D. Fully Dynamic Constrained Delaunay Triangulations. In Geometric Modeling for Scientific Visualization; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 241–257.

- Shewchuk, J.R. Mesh generation for domains with small angles. In Proceedings of the Sixteenth Annual Symposium on Computational Geometry, New York, NY, USA, 1 May 2000; pp. 1–10.

- Balampanis, F.; Maza, I.; Ollero, A. Spiral-like coverage path planning for multiple heterogeneous UAS operating in coastal regions. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Miami, FL, USA, 13–16 June 2017; pp. 617–624.

- Balampanis, F.; Maza, I.; Ollero, A. Area Partition for Coastal Regions with Multiple UAS. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2017, 88, 751–766.

- Hayat, S.; Yanmaz, E.; Brown, T.X.; Bettstetter, C. Multi-objective UAV path planning for search and rescue. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Singapore, 29 May–3 June 2017; pp. 5569–5574.

- Trujillo, M.M.; Darrah, M.; Speransky, K.; DeRoos, B.; Wathen, M. Optimized flight path for 3D mapping of an area with structures using a multirotor. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Arlington, VA, USA, 7–10 June 2016; pp. 905–910.

- Darrah, M.; Trujillo, M.M.; Speransky, K.; Wathen, M. Optimized 3D mapping of a large area with structures using multiple multirotors. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Miami, FL, USA, 13–16 June 2017; pp. 716–722.

- Lawrance, N.; Sukkarieh, S. Wind Energy Based Path Planning for a Small Gliding Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. In Proceedings of the AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference, American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Chicago, IL, USA, 10–13 August 2009.

- Torres, M.; Pelta, D.A.; Verdegay, J.L.; Torres, J.C. Coverage Path Planning with Unmanned Aerial Vehicles for 3D Terrain Reconstruction. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 55, 441–451.

- Coombes, M.; Chen, W.-H.; Liu, C. Boustrophedon Coverage Path Planning for UAV Aerial Surveys in Wind. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Miami, FL, USA, 13–16 June 2017; pp. 1563–1571.

- Coombes, M.; Fletcher, T.; Chen, W.-H.; Liu, C. Optimal Polygon Decomposition for UAV Survey Coverage Path Planning in Wind. Sensors 2018, 18, 2132.

- Cabreira, T.M.; Franco, C.D.; Ferreira, P.R.; Buttazzo, G.C. Energy-Aware Spiral Coverage Path Planning for UAV Photogrammetric Applications. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2018, 3, 3662–3668.

- Di Franco, C.; Buttazzo, G. Energy-Aware Coverage Path Planning of UAVs. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Autonomous Robot Systems and Competitions, Vila Real, Portugal, 8–10 April 2015; pp. 111–117.

- Li, D.; Wang, X.; Sun, T. Energy-Optimal Coverage Path Planning on Topographic Map for Environment Survey with Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Electron. Lett. 2016, 52, 699–701.

- Artemenko, O.; Dominic, O.J.; Andryeyev, O.; Mitschele-Thiel, A. Energy-aware trajectory planning for the localization of mobile devices using an unmanned aerial vehicle. In Proceedings of the 2016 25th International Conference on Computer Communication and Networks (ICCCN), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 1–4 August 2016; pp. 1–9.

- Ahmadzadeh, A.; Keller, J.; Pappas, G.; Jadbabaie, A.; Kumar, V. An optimization-based approach to time-critical cooperative surveillance and coverage with UAVs. In Experimental Robotics: The 10th International Symposium on Experimental Robotics; Khatib, O., Kumar, V., Rus, D., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 491–500.

- Araujo, J.F.; Sujit, P.B.; Sousa, J.B. Multiple UAV area decomposition and coverage. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Symposium on Computational Intelligence for Security and Defense Applications (CISDA), Singapore, 16–19 April 2013; pp. 30–37.

- Majeed, A.; Lee, S. A New Coverage Flight Path Planning Algorithm Based on Footprint Sweep Fitting for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Navigation in Urban Environments. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1470.

- Majeed, A.; Hwang, S.O. A Multi-Objective Coverage Path Planning Algorithm for UAVs to Cover Spatially Distributed Regions in Urban Environments. Aerospace 2021, 8, 343.

- Cheng, C.-T.; Fallahi, K.; Leung, H.; Tse, C.K. Cooperative Path Planner for UAVs Using ACO Algorithm with Gaussian Distribution Functions. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems, Taipei, Taiwan, 24–27 May 2009; pp. 173–176.

- Kuiper, E.; Nadjm-Tehrani, S. Mobility Models for UAV Group Reconnaissance Applications. In Proceedings of the 2006 International Conference on Wireless and Mobile Communications (ICWMC’06), Bucharest, Romania, 29–31 July 2006; p. 33.