| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Arnolda Jakovija | + 1837 word(s) | 1837 | 2021-08-24 05:57:41 | | | |

| 2 | Amina Yu | -24 word(s) | 1813 | 2022-01-19 02:52:55 | | |

Video Upload Options

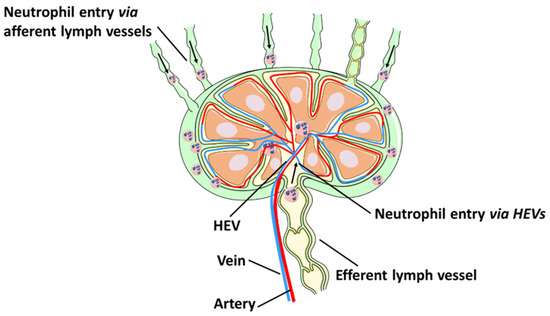

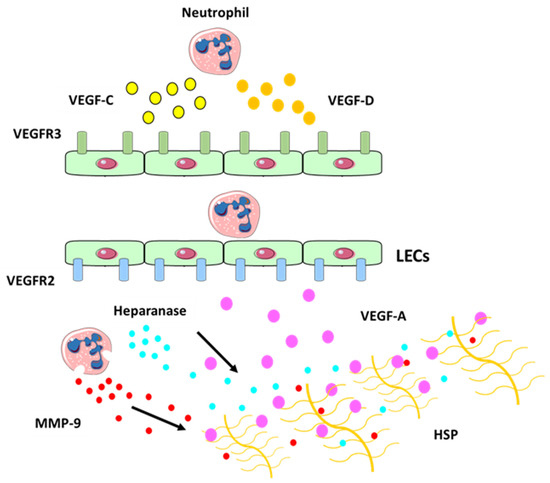

The lymphatic system is a complex network of lymphatic vessels and lymph nodes designed to balance fluid homeostasis and facilitate host immune defence. Neutrophils are rapidly recruited to sites of inflammation to provide the first line of protection against microbial infections. The traditional view of neutrophils as short-lived cells, whose role is restricted to providing sterilizing immunity at sites of infection, is rapidly evolving to include additional functions at the interface between the innate and adaptive immune systems. Neutrophils travel via the lymphatics from the site of inflammation to transport antigens to lymph nodes. They can also enter lymph nodes from the blood by crossing high endothelial venules. Neutrophil functions in draining lymph nodes include pathogen control and modulation of adaptive immunity. Another facet of neutrophil interactions with the lymphatic system is their ability to promote lymphangiogenesis in draining lymph nodes and inflamed tissues.

1. Introduction

2. Neutrophil Contributions to Lymphangiogenesis

3. Conclusions and Perspectives

References

- Harvey, N.L. Lymphatic Vascular Development. Heart Dev. Regen. 2010, 543–565.

- Jackson, D.G. Leucocyte Trafficking via the Lymphatic Vasculature— Mechanisms and Consequences. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 471.

- Liao, S.; von der Weid, P.-Y. Inflammation-induced lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic dysfunction. Angiogenesis 2014, 17, 325–334.

- Lok, L.S.C.; Dennison, T.W.; Mahbubani, K.M.; Saeb-Parsy, K.; Chilvers, E.R.; Clatworthy, M.R. Phenotypically distinct neutrophils patrol uninfected human and mouse lymph nodes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 19083–19089.

- Bogoslowski, A.; Wijeyesinghe, S.; Lee, W.-Y.; Chen, C.-S.; Alanani, S.; Jenne, C.; Steeber, D.A.; Scheiermann, C.; Butcher, E.C.; Masopust, D.; et al. Neutrophils Recirculate through Lymph Nodes to Survey Tissues for Pathogens. J. Immunol. 2020, 204, 2552–2561.

- Rosales, C. Neutrophil: A Cell with Many Roles in Inflammation or Several Cell Types? Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 113.

- Wang, J.; Hossain, M.; Thanabalasuriar, A.; Gunzer, M.; Meininger, C.; Kubes, P. Visualizing the function and fate of neutrophils in sterile injury and repair. Science 2017, 358, 111–116.

- Mathias, J.R.; Perrin, B.J.; Liu, T.X.; Kanki, J.; Look, A.T.; Huttenlocher, A. Resolution of inflammation by retrograde chemotaxis of neutrophils in transgenic zebrafish. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2006, 80, 1281–1288.

- Hampton, H.R.; Bailey, J.; Tomura, M.; Brink, R.; Chtanova, T. Microbe-dependent lymphatic migration of neutrophils modulates lymphocyte proliferation in lymph nodes. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7139.

- Abadie, V.r.; Badell, E.; Douillard, P.; Ensergueix, D.; Leenen, P.J.M.; Tanguy, M.; Fiette, L.; Saeland, S.; Gicquel, B.; Winter, N. Neutrophils rapidly migrate via lymphatics after Mycobacterium bovis BCG intradermal vaccination and shuttle live bacilli to the draining lymph nodes. Blood 2005, 106, 1843–1850.

- Gorlino, C.V.; Ranocchia, R.P.; Harman, M.F.; García, I.A.; Crespo, M.I.; Morón, G.; Maletto, B.A.; Pistoresi-Palencia, M.C. Neutrophils Exhibit Differential Requirements for Homing Molecules in Their Lymphatic and Blood Trafficking into Draining Lymph Nodes. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 1966–1974.

- Arokiasamy, S.; Zakian, C.; Dilliway, J.; Wang, W.; Nourshargh, S.; Voisin, M.-B. Endogenous TNFα orchestrates the trafficking of neutrophils into and within lymphatic vessels during acute inflammation. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44189.

- Kamenyeva, O.; Boularan, C.; Kabat, J.; Cheung, G.Y.C.; Cicala, C.; Yeh, A.J.; Chan, J.L.; Periasamy, S.; Otto, M.; Kehrl, J.H. Neutrophil Recruitment to Lymph Nodes Limits Local Humoral Response to Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1004827.

- Brackett, C.M.; Muhitch, J.B.; Evans, S.S.; Gollnick, S.O. IL-17 Promotes Neutrophil Entry into Tumor-Draining Lymph Nodes following Induction of Sterile Inflammation. J. Immunol. 2013, 191, 4348–4357.

- Bogoslowski, A.; Butcher, E.C.; Kubes, P. Neutrophils recruited through high endothelial venules of the lymph nodes via PNAd intercept disseminating Staphylococcus aureus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 2449–2454.

- Tammela, T.; Alitalo, K. Lymphangiogenesis: Molecular mechanisms and future promise. Cell 2010, 140, 460–476.

- Baluk, P.; Tammela, T.; Ator, E.; Lyubynska, N.; Achen, M.G.; Hicklin, D.J.; Jeltsch, M.; Petrova, T.V.; Pytowski, B.; Stacker, S.A.; et al. Pathogenesis of persistent lymphatic vessel hyperplasia in chronic airway inflammation. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 247–257.

- Tan, K.W.; Chong, S.Z.; Wong, F.H.S.; Evrard, M.; Tan, S.M.-L.; Keeble, J.; Kemeny, D.M.; Ng, L.G.; Abastado, J.-P.; Angeli, V. Neutrophils contribute to inflammatory lymphangiogenesis by increasing VEGF-A bioavailability and secreting VEGF-D. Blood 2013, 122, 3666–3677.

- Christiansen, A.; Detmar, M. Lymphangiogenesis and Cancer. Genes Cancer 2011, 2, 1146–1158.

- Bálint, L.; Jakus, Z. Mechanosensation and Mechanotransduction by Lymphatic Endothelial Cells Act as Important Regulators of Lymphatic Development and Function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3955.

- Coso, S.; Bovay, E.; Petrova, T.V. Pressing the right buttons: Signaling in lymphangiogenesis. Blood 2014, 123, 2614–2624.

- Secker, G.A.; Harvey, N.L. VEGFR signaling during lymphatic vascular development: From progenitor cells to functional vessels. Dev. Dyn. 2015, 244, 323–331.

- Schwager, S.; Detmar, M. Inflammation and Lymphatic Function. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 308.

- Huggenberger, R.; Ullmann, S.; Proulx, S.T.; Pytowski, B.; Alitalo, K.; Detmar, M. Stimulation of lymphangiogenesis via VEGFR-3 inhibits chronic skin inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 2010, 207, 2255–2269.

- Kajiya, K.; Detmar, M. An important role of lymphatic vessels in the control of UVB-induced edema formation and inflammation. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2006, 126, 919–921.

- D’Alessio, S.; Correale, C.; Tacconi, C.; Gandelli, A.; Pietrogrande, G.; Vetrano, S.; Genua, M.; Arena, V.; Spinelli, A.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; et al. VEGF-C-dependent stimulation of lymphatic function ameliorates experimental inflammatory bowel disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 3863–3878.

- Jurisic, G.; Sundberg, J.P.; Detmar, M. Blockade of VEGF receptor-3 aggravates inflammatory bowel disease and lymphatic vessel enlargement. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2013, 19, 1983–1989.

- Guo, R.; Zhou, Q.; Proulx, S.T.; Wood, R.; Ji, R.C.; Ritchlin, C.T.; Pytowski, B.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, Y.J.; Schwarz, E.M.; et al. Inhibition of lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic drainage via vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 blockade increases the severity of inflammation in a mouse model of chronic inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 60, 2666–2676.

- Amouzegar, A.; Chauhan, S.K.; Dana, R. Alloimmunity and Tolerance in Corneal Transplantation. J. Immunol. 2016, 196, 3983–3991.

- Hou, Y.; Bock, F.; Hos, D.; Cursiefen, C. Lymphatic Trafficking in the Eye: Modulation of Lymphatic Trafficking to Promote Corneal Transplant Survival. Cells 2021, 10, 1661.

- Ribatti, D.; Crivellato, E. Immune cells and angiogenesis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2009, 13, 2822–2833.

- Cueni, L.N.; Detmar, M. New Insights into the Molecular Control of the Lymphatic Vascular System and its Role in Disease. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2006, 126, 2167–2177.

- Veikkola, T.; Jussila, L.; Makinen, T.; Karpanen, T.; Jeltsch, M.; Petrova, T.V.; Kubo, H.; Thurston, G.; McDonald, D.M.; Achen, M.G.; et al. Signalling via vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-3 is sufficient for lymphangiogenesis in transgenic mice. Embo J. 2001, 20, 1223–1231.

- Baldwin, M.E.; Halford, M.M.; Roufail, S.; Williams, R.A.; Hibbs, M.L.; Grail, D.; Kubo, H.; Stacker, S.A.; Achen, M.G. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor D Is Dispensable for Development of the Lymphatic System. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 2441–2449.

- Houck, K.A.; Leung, D.W.; Rowland, A.M.; Winer, J.; Ferrara, N. Dual regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor bioavailability by genetic and proteolytic mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 26031–26037.

- Poltorak, Z.; Cohen, T.; Sivan, R.; Kandelis, Y.; Spira, G.; Vlodavsky, I.; Keshet, E.; Neufeld, G. VEGF145, a Secreted Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Isoform That Binds to Extracellular Matrix. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 7151–7158.

- Koch, S.; Claesson-Welsh, L. Signal Transduction by Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptors. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a006502.

- Selders, G.S.; Fetz, A.E.; Radic, M.Z.; Bowlin, G.L. An overview of the role of neutrophils in innate immunity, inflammation and host-biomaterial integration. Regen. Biomater. 2017, 4, 55–68.

- Okuda, K.S.; Misa, J.P.; Oehlers, S.H.; Hall, C.J.; Ellett, F.; Alasmari, S.; Lieschke, G.J.; Crosier, K.E.; Crosier, P.S.; Astin, J.W. A zebrafish model of inflammatory lymphangiogenesis. Biol. Open 2015, 4, 1270–1280.

- Sano, M.; Sasaki, T.; Hirakawa, S.; Sakabe, J.; Ogawa, M.; Baba, S.; Zaima, N.; Tanaka, H.; Inuzuka, K.; Yamamoto, N.; et al. Lymphangiogenesis and Angiogenesis in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89830.

- Ji, R.C. Lymph node lymphangiogenesis: A new concept for modulating tumor metastasis and inflammatory process. Histol. Histopathol. 2009, 24, 377–384.

- Shrestha, B.; Hashiguchi, T.; Ito, T.; Miura, N.; Takenouchi, K.; Oyama, Y.; Kawahara, K.-i.; Tancharoen, S.; Ki-i, Y.; Arimura, N.; et al. B Cell-Derived Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A Promotes Lymphangiogenesis and High Endothelial Venule Expansion in Lymph Nodes. J. Immunol. 2010, 184, 4819–4826.

- Kataru, R.P.; Jung, K.; Jang, C.; Yang, H.; Schwendener, R.A.; Baik, J.E.; Han, S.H.; Alitalo, K.; Koh, G.Y. Critical role of CD11b+ macrophages and VEGF in inflammatory lymphangiogenesis, antigen clearance, and inflammation resolution. Blood 2009, 113, 5650–5659.

- Chyou, S.; Ekland, E.H.; Carpenter, A.C.; Tzeng, T.-C.J.; Tian, S.; Michaud, M.; Madri, J.A.; Lu, T.T. Fibroblast-Type Reticular Stromal Cells Regulate the Lymph Node Vasculature. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 3887–3896.

- Hampton, H.R.; Chtanova, T. The lymph node neutrophil. Semin. Immunol. 2016, 28, 129–136.

- Hampton, H.R.; Chtanova, T. Lymphatic Migration of Immune Cells. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1168.

- Bogoslowski, A.; Kubes, P. Lymph Nodes: The Unrecognized Barrier against Pathogens. ACS Infect. Dis. 2018, 4, 1158–1161.

- Duffy, D.; Perrin, H.; Abadie, V.; Benhabiles, N.; Boissonnas, A.; Liard, C.; Descours, B.; Reboulleau, D.; Bonduelle, O.; Verrier, B.; et al. Neutrophils transport antigen from the dermis to the bone marrow, initiating a source of memory CD8+ T cells. Immunity 2012, 37, 917–929.

- Puerta-Arias, J.D.; Pino-Tamayo, P.A.; Arango, J.C.; Gonzalez, A. Depletion of Neutrophils Promotes the Resolution of Pulmonary Inflammation and Fibrosis in Mice Infected with Paracoccidioides brasiliensis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163985.

- Soehnlein, O.; Libby, P. Targeting inflammation in atherosclerosis—From experimental insights to the clinic. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 589–610.

- Arseneau, K.; Cominelli, F. Targeting Leukocyte Trafficking for the Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin. Pharm. 2015, 97, 22–28.

- Kerjaschki, D.; Huttary, N.; Raab, I.; Regele, H.; Bojarski-Nagy, K.; Bartel, G.; Kröber, S.M.; Greinix, H.; Rosenmaier, A.; Karlhofer, F.; et al. Lymphatic endothelial progenitor cells contribute to de novo lymphangiogenesis in human renal transplants. Nat. Med. 2006, 12, 230–234.

- Cursiefen, C.; Cao, J.; Chen, L.; Liu, Y.; Maruyama, K.; Jackson, D.; Kruse, F.E.; Wiegand, S.J.; Dana, M.R.; Streilein, J.W. Inhibition of Hemangiogenesis and Lymphangiogenesis after Normal-Risk Corneal Transplantation by Neutralizing VEGF Promotes Graft Survival. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2004, 45, 2666.

- Cui, Y.; Liu, K.; Monzon-Medina, M.E.; Padera, R.F.; Wang, H.; George, G.; Toprak, D.; Abdelnour, E.; D’Agostino, E.; Goldberg, H.J.; et al. Therapeutic lymphangiogenesis ameliorates established acute lung allograft rejection. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 4255–4268.

- Kajiya, K.; Hirakawa, S.; Detmar, M. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-A Mediates Ultraviolet B-Induced Impairment of Lymphatic Vessel Function. Am. J. Pathol. 2006, 169, 1496–1503.