| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Niel Karrow | + 3395 word(s) | 3395 | 2021-12-08 04:43:29 | | | |

| 2 | Dean Liu | Meta information modification | 3395 | 2022-01-19 01:33:52 | | | | |

| 3 | Dean Liu | Meta information modification | 3395 | 2022-01-21 09:11:04 | | | | |

| 4 | Dean Liu | Meta information modification | 3395 | 2022-01-21 09:12:04 | | | | |

| 5 | Dean Liu | Meta information modification | 3395 | 2022-01-21 09:16:53 | | | | |

| 6 | Dean Liu | Meta information modification | 3395 | 2022-01-21 09:18:29 | | | | |

| 7 | Dean Liu | Meta information modification | 3395 | 2022-01-21 09:19:17 | | | | |

| 8 | Dean Liu | Meta information modification | 3395 | 2022-01-21 09:20:44 | | | | |

| 9 | Dean Liu | + 2 word(s) | 3397 | 2022-01-21 09:27:05 | | |

Video Upload Options

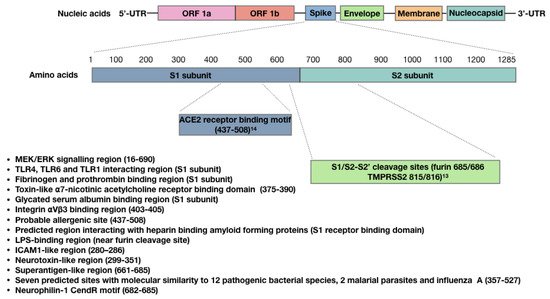

The main host target receptor for the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein is angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), which is involved in maintaining blood pressure and vascular remodeling, and is expressed on adipocytes, other cells at mucosal surfaces, and in the vasculature, heart, kidneys, pancreas and brain.

1. Bioactivity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein

2. The SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Triggers Autoimmune Responses

Autoimmune diseases can be triggered by viral infections and some vaccines, and are more common to females [46]. There is mounting evidence to support the hypothesis that SARS-CoV-2 infection is a risk factor for autoimmune disease in predisposed individuals [47][48][49][50]. Autoimmune diseases manifest as hyper-stimulated immune responses against autoantigens, which are normally tolerated by the immune system. The proposed mechanisms of autoimmune response during SARS-CoV-2 infection have been previously discussed [50][51] and include molecular mimicry, bystander activation, epitope spreading, and polyclonal lymphocyte activation by SARS-CoV-2 superantigens. Molecular mimicry describes structural similarities between SARS-CoV-2 antigens and autoantigens that are recognized by immune cells (i.e., cytotoxic T cells) and immunoglobulins (i.e., autoantibodies and antiphospholipid antibodies) in cross-reactive epitopes. When autoantigens are targeted by these effectors, this can lead to immune-mediated tissue damage, and if autoreactive memory B-cells and T-cells are generated, this can lead to chronic disease. Bystander activation involves immune-mediated tissue damage resulting from a nonspecific and over-reactive antiviral innate immune response, such as the cytokine storm that has been described in severely impacted COVID-19 patients. In this case, tissue and cellular components become exposed during damage, and are then ingested by phagocytic cells and presented as autoantigens to autoreactive T helper and cytotoxic T cells, which contribute to ongoing immune-mediated pathology. Epitope spreading refers to ongoing sensitization to autoantigens as the disease progresses, which can lead to progressive and chronic disease. A recent study by Zuo et al. [52] implicated anti-NET antibodies as potential contributors of COVID-19 thromboinflammation; NETs are neutrophil extracellular traps that are produced by hyperactive neutrophils that have either come into contact with SARS-CoV-2 or have been activated by platelets and prothrombotic antibodies. These NETs are cytotoxic to pulmonary endothelial cells, and Zuo et al. discovered that anti-NET antibodies contribute to NET stabilization, which may impair their clearance and exacerbate thromboinflammation. Very recently, NETs were also implicated in VIPIT following the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine [53], but the potential involvement of anti-NET antibodies remains to be determined.

SARS-CoV-2 spike protein superantigen activity was discussed earlier. Superantigens are known to trigger the cytokine storm that can lead to immune-mediated multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, and this is often followed by immune suppression that can lead to persistent infection [54]. Superantigens such as SEB have been shown to exacerbate autoimmune disorders (i.e., experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and experimental multiple sclerosis) in mice models [55]. Recently, Jacobs proposed that long-COVID could be due in part to SARS-CoV-2 superantigen-mediated immune suppression, leading to persistent systemic SARS-CoV-2 infection [51]. In terms of pregnancy, prenatal exposure of rats to SEB was shown to attenuate the development and function of regulatory T cells in adult offspring [56] and alter the behaviour (i.e., increased anxiety and locomotion) of mice offspring [57].

Among the proposed mechanisms contributing to autoimmune responses during COVID-19, molecular mimicry has recently taken the front stage. A number of studies have found homologies between SARS-CoV-2 amino acid and human protein amino acid residues [58][59], and more specifically, between the spike protein and human proteins [60][61][62]. Additionally, some of these cross-reactive regions were immunogenic epitopes, meaning that they can bind to MHC I or II molecules on antigen-presenting cells, thereby activating autoreactive B and T cells that elicit an autoimmune response. Martínez et al. [61] for example, identified common host-like motifs in the SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins nested in B and T cell epitopes. Morsy and Morsy also identified SARS-CoV-2 spike protein epitopes for MHC I and II molecules that were cross-reactive with the homeobox protein 2.1 (NKX2-1) and ATP-binding cassette sub-family A member 3 (ABCA3) lung proteins [62]. Kanduc and Shoenfeld searched for overlapping SARS-CoV-2 spike protein hexa- and hepta-peptides across mammalian proteomes and found a large number of matches within the human proteome; these authors stated that this is evidence of molecular mimicry, contributing to SARS-CoV-2-associated diseases [60]. Dotan et al. [63] also recently identified 41 immunogenic penta-peptides within the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein that are shared with 27 human proteins related to oogenesis, placentation and/or decidualization, implicating molecular mimicry as a potential contributor to female infertility. Vojdani and Kharrazian also demonstrated that anti-SARS-CoV-2 human IgG monoclonal antibodies cross-reacted with 28 out of 55 human tissue antigens derived from various tissues (i.e., mucosal and blood-brain barrier, thyroid, central nervous system, muscle and connective tissue), and BLAST searches revealed similarities and homologies between the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and human proteins [64]. In terms of the COVID-19 vaccines, molecular mimicry has also been implicated in myocarditis, an AVR associated with the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines [65]. Huynh et al. [66] also recently identified autoantibodies as the potential cause of VIPIT; these autoantibodies were found to bind to PF4 and allowed for Fc receptor-mediated activation of platelets, which could initiate coagulation, leading to thrombocytopenia and thrombosis. These findings have raised concerns over the possibility that anti-SARS-CoV-2 spike protein antibodies may be responsible for VIPIT. Greinacher A et al. [67] investigated this hypothesis and found that SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and PF4 share at least one similar epitope. However, when they used purified anti-PF4 antibodies from patients with VIPIT, none of the anti-PF4 antibodies cross-reacted with SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. They, therefore, concluded that the vaccine-induced immune response against the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein was not the trigger causing VIPIT.

Anti-idiotypic antibodies were also proposed as an autoimmune response following SARS-CoV-2 infection [68]. In this study, Arthur et al. detected ACE2 autoantibodies in convalescent plasma from previously infected patients, which were also correlated with anti-spike protein RBD antibody levels. Since patients with ACE2 autoantibodies also had less plasma ACE2 activity, these authors hypothesized that the ACE2 autoantibodies were anti-idiotypic antibodies that could interfere with ACE2 function and contribute to post-acute sequelae of SARC-CoV-2 infection (PASC, or “long-COVID”). We are unaware of ACE2 autoantibody levels being assessed following COVID-19 vaccination, so this warrants further investigation.

Collectively, the above autoimmune responses triggered by infection with SARS-CoV-2 or the COVID-19 vaccines suggest potential negative outcomes on fetal and neonatal development, and this should be explored in future studies. As with APS, cytokine storms and thromboinflammation are of concern—as is the potential for autoantibody responses that could target fetal/neonatal proteins.

3. The SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein and Antibody-Dependent Enhancement

While antibodies have a number of important effector activities against SARS-CoV-2, including limiting viral attachment to epithelial cells and viral neutralization, non-neutralizing antibodies that enhance viral entry into host cells can sometimes also be generated; this immunological phenomenon is referred to as antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE). Since the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, concerns have been raised about the possibility of ADE occurring, as it has been reported that both SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV infect various animal models via ADE [69][70]. Ricke [70] proposed that SARS-CoV-2 may leverage Fc receptors for host cell invasion, and this may contribute to cytokine storms, leading to adult multi-system inflammatory syndrome, and also infant MIS-C—the latter presumably being mediated by passive transfer of maternal anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies that have become bound to Fc receptors on infant mast cells or macrophages [71]. While the potential risk of this type of ADE occurring in response to COVID-19 vaccines remains unknown, experience with SARS-CoV-1 spike protein vaccines demonstrates that it is indeed a possibility which warrants further investigation [70].

A second type of ADE involves non-neutralizing antibodies binding to and then eliciting conformational changes to viral proteins that can lead to enhanced viral adhesion to host cells [69]. Liu et al. [72] recently screened a panel of anti-SARS-CoV-2 spike protein monoclonal antibodies derived from COVID-19 patients and found that some of these antibodies that bind to the N-terminal domain of the spike protein induce open confirmation of the RBD, which enhances the binding capacity of the spike protein to ACE2 and the infectivity of SARS-CoV-2. Interestingly, these infection-enhancing antibodies have been identified in both uninfected and infected blood donors and have been detected at high levels in severe COVID-19 patients; their presence in uninfected people implies that these individuals may be at risk of severe COVID-19 if they later become infected with SARS-CoV-2 [72]. Another recent study has suggested that people may be at risk of infection by the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant if they were vaccinated against the Wuhan strain spike sequence because the Delta variant is well-recognized by infection-enhancing antibodies targeting the N-terminal domain of the spike protein [73].

A number of murine studies have demonstrated that non-neutralizing maternal antibodies can increase the risk of neonatal disease. For example, pregnant mice infected with different strains of Dengue virus (DENV) display maternal anti-DENV IgG that is passively transferred during gestation and enhances the severity of offspring disease (i.e., hepatocyte vacuolation, vascular leakage, lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia) following infection with the heterotypic strain [74], and breastfeeding has been shown to extend the window of ADE [75]. In terms of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, the passive transfer of anti-SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies has been detected in milk samples collected from women with COVID-19 [76]; however, non-neutralizing antibodies were not assessed. Anti-spike protein antibodies (IgG and IgA) have also been detected in milk samples from lactating mothers who were vaccinated with SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines [77]; however, their neutralization/non-neutralization status was not assessed. Therefore, we have no data to determine whether or not a passive transfer of ADE can occur during SARS-CoV-2 infection or COVID-19 vaccination, and so this warrants further investigation.

References

- Gengler, C.; Dubruc, E.; Favre, G.; Greub, G.; de Leval, L.; Baud, D. SARS-CoV-2 ACE-receptor detection in the placenta throughout pregnancy. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, 489–490.

- Dhaundiyal, A.; Kumari, P.; Jawalekar, S.S.; Chauhan, G.; Kalra, S.; Navik, U. Is highly expressed ACE 2 in pregnant women “a curse” in times of COVID-19 pandemic? Life Sci. 2021, 264, 118676.

- Argueta, L.B.; Lacko, L.A.; Bram, Y.; Tada, T.; Carrau, L.; Zhang, T.; Uhl, S.; Lubor, B.C.; Chandar, V.; Gil, C.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infects Syncytiotrophoblast and Activates Inflammatory Responses in the Placenta. bioRxiv 2021, 17, 2021.

- Flores-Pliego, A.; Miranda, J.; Vega-Torreblanca, S.; Valdespino-Vázquez, Y.; Helguera-Repetto, C.; Espejel-Nuñez, A.; Borboa-Olivares, H.; Espino Y Sosa, S.; Mateu-Rogell, P.; León-Juárez, M.; et al. Molecular Insights into the Thrombotic and Microvascular Injury in Placental Endothelium of Women with Mild or Severe COVID-19. Cells 2021, 10, 364.

- Ogata, A.F.; Cheng, C.-A.; Desjardins, M.; Senussi, Y.; Sherman, A.C.; Powell, M.; Novack, L.; Von, S.; Li, X.; Baden, L.R.; et al. Circulating SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Antigen Detected in the Plasma of mRNA-1273 Vaccine Recipients. Clin Infect Dis. 2021, 20, ciab465.

- Lei, Y.; Zhang, J.; Schiavon, C.R.; He, M.; Chen, L.; Shen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, Q.; Cho, Y.; Andrade, L.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Impairs Endothelial Function via Downregulation of ACE2. bioRxiv 2021, 128, 1323–1326.

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhao, P.; Yang, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhang, L.; Li, Z.; Jia, K.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein enhances ACE2 expression via facilitating Interferon effects in bronchial epithelium. Immunol. Lett. 2021, 237, 33–41.

- Ratajczak, M.Z.; Bujko, K.; Ciechanowicz, A.; Sielatycka, K.; Cymer, M.; Marlicz, W.; Kucia, M. SARS-CoV-2 Entry Receptor ACE2 Is Expressed on Very Small CD45- Precursors of Hematopoietic and Endothelial Cells and in Response to Virus Spike Protein Activates the Nlrp3 Inflammasome. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2021, 17, 266–277.

- Ropa, J.; Cooper, S.; Capitano, M.L.; Van’t Hof, W.; Broxmeyer, H.E. Human Hematopoietic Stem, Progenitor, and Immune Cells Respond Ex Vivo to SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2021, 17, 253–265.

- Colunga Biancatelli, R.M.L.; Solopov, P.A.; Sharlow, E.R.; Lazo, J.S.; Marik, P.E.; Catravas, J.D. The SARS-CoV-2 spike protein subunit S1 induces COVID-19-like acute lung injury in Κ18-hACE2 transgenic mice and barrier dysfunction in human endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2021, 321, L477–L484.

- Suzuki, Y.J.; Nikolaienko, S.I.; Dibrova, V.A.; Dibrova, Y.V.; Vasylyk, V.M.; Novikov, M.Y.; Shults, N.V.; Gychka, S.G. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein-mediated cell signaling in lung vascular cells. Vascul Pharmacol. 2021, 137, 106823.

- Chen, I.-Y.; Chang, S.C.; Wu, H.-Y.; Yu, T.-C.; Wei, W.-C.; Lin, S.; Chien, C.L.; Chang, M.F. Upregulation of the chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 via a severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike-ACE2 signaling pathway. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 7703–7712.

- Nader, D.; Fletcher, N.; Curley, G.F.; Kerrigan, S.W. SARS-CoV-2 uses major endothelial integrin αvβ3 to cause vascular dysregulation in-vitro during COVID-19. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253347.

- Gautam, I.; Storad, Z.; Filipiak, L.; Huss, C.; Meikle, C.K.; Worth, R.G.; Wuescher, L.M. From Classical to Unconventional: The Immune Receptors Facilitating Platelet Responses to Infection and Inflammation. Biology 2020, 9, 343.

- Shen, S.; Zhang, J.; Fang, Y.; Lu, S.; Wu, J.; Zheng, X.; Deng, F. SARS-CoV-2 interacts with platelets and megakaryocytes via ACE2-independent mechanism. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 72.

- Campbell, R.A.; Boilard, E.; Rondina, M.T. Is there a role for the ACE2 receptor in SARS-CoV-2 interactions with platelets? J. Thromb. Haemost. 2021, 19, 46–50.

- Choudhury, A.; Mukherjee, S. In silico studies on the comparative characterization of the interactions of SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein with ACE-2 receptor homologs and human TLRs. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 2105–2113.

- Shirato, K.; Kizaki, T. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein S1 subunit induces pro-inflammatory responses via toll-like receptor 4 signaling in murine and human macrophages. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06187.

- Andonegui, G.; Kerfoot, S.M.; McNagny, K.; Ebbert, K.V.J.; Patel, K.D.; Kubes, P. Platelets express functional Toll-like receptor-4. Blood 2005, 106, 2417–2423.

- Ouyang, W.; Xie, T.; Fang, H.; Gao, C.; Stantchev, T.; Clouse, K.A.; Yuan, K.; Ju, T.; Frucht, D.M. Variable Induction of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines by Commercial SARS CoV-2 Spike Protein Reagents: Potential Impacts of LPS on In Vitro Modeling and Pathogenic Mechanisms In Vivo. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7540.

- Petruk, G.; Puthia, M.; Petrlova, J.; Samsudin, F.; Strömdahl, A.-C.; Cerps, S.; Uller, L.; Kjellström, S.; Bond, P.J.; Schmidtchen, A.A. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein binds to bacterial lipopolysaccharide and boosts proinflammatory activity. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 12, 916–932.

- Grobbelaar, L.M.; Venter, C.; Vlok, M.; Ngoepe, M.; Laubscher, G.J.; Lourens, P.J.; Steenkamp, J.; Kell, D.B.; Pretorius, E. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein S1 induces fibrin(ogen) resistant to fibrinolysis: Implications for microclot formation in COVID-19. Biosci Rep. 2021, 41, BSR20210611.

- IIes, J.K.; Zmuidinaite, R.; Sadee, C.; Gardiner, A.; Lacey, J.; Harding, S.; Ule, J.; Roblett, D.; Heeney, J.L.; Baxendale, H.E.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Binding of Glycated Serum Albumin—Its Potential Role in the Pathogenesis of the COVID-19 Clinical Syndromes and Bias towards Individuals with Pre-Diabetes/Type 2 Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases . 2021, p. 21258871. Available online: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.06.14.21258871v3 (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Lagoumintzis, G.; Chasapis, C.T.; Alexandris, N.; Kouretas, D.; Tzartos, S.; Eliopoulos, E.; Farsalinos, K.; Poulas, K. Nicotinic cholinergic system and COVID-19: In silico identification of interactions between α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor and the cryptic epitopes of SARS-Co-V and SARS-CoV-2 Spike glycoproteins. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021, 149, 112009.

- Cantuti-Castelvetri, L.; Ojha, R.; Pedro, L.D.; Djannatian, M.; Franz, J.; Kuivanen, S.; van der Meer, F.; Kallio, K.; Kaya, T.; Anastasina, M.; et al. Neuropilin-1 facilitates SARS-CoV-2 cell entry and infectivity. Science 2020, 370, 856–860.

- Shiers, S.; Ray, P.R.; Wangzhou, A.; Tatsui, C.E.; Rhines, L.; Li, Y.; Uhelski, M.L.; Dougherty, P.M.; Price, T.J. ACE2 expression in human dorsal root ganglion sensory neurons: Implications for SARS-CoV-2 virus-induced neurological effects . May 2020, p. 2020.05.28.122374. Available online: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.05.28.122374v1 (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- Mao, L.; Jin, H.; Wang, M.; Hu, Y.; Chen, S.; He, Q.; Chang, J.; Hong, C.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, D.; et al. Neurologic Manifestations of Hospitalized Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020, 77, 683–690.

- Daly, J.L.; Simonetti, B.; Klein, K.; Chen, K.-E.; Williamson, M.K.; Antón-Plágaro, C.; Shoemark, D.K.; Simón-Gracia, L.; Bauer, M.; Hollandi, R.; et al. Neuropilin-1 is a host factor for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Science 2020, 370, 861–865.

- Moutal, A.; Martin, L.F.; Boinon, L.; Gomez, K.; Ran, D.; Zhou, Y.; Stratton, H.J.; Cai, S.; Luo, S.; Gonzalez, K.B.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein co-opts VEGF-A/neuropilin-1 receptor signaling to induce analgesia. Pain 2021, 162, 243–252.

- Selvaraj, G.; Kaliamurthi, S.; Peslherbe, G.H.; Wei, D.-Q. Are the Allergic Reactions of COVID-19 Vaccines Caused by mRNA Constructs or Nanocarriers? Immunological Insights. Interdiscip Sci. 2021, 13, 344–347.

- Idrees, D.; Kumar, V. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein interactions with amyloidogenic proteins: Potential clues to neurodegeneration. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 554, 94–98.

- Classen, J.B. COVID-19 RNA Based Vaccines and the Risk of Prion Disease. Microbiol. Infect Dis. 2021, 5. Available online: https://scivisionpub.com/pdfs/covid19-rna-based-vaccines-and-the-risk-of-prion-disease-1503.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- Dakal, T.C. Antigenic sites in SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD show molecular similarity with pathogenic antigenic determinants and harbors peptides for vaccine development. Immunobiology 2021, 226, 152091.

- Noval Rivas, M.; Porritt, R.A.; Cheng, M.H.; Bahar, I.; Arditi, M. COVID-19-associated multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C): A novel disease that mimics toxic shock syndrome-the superantigen hypothesis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 147, 57–59.

- Cheng, M.H.; Zhang, S.; Porritt, R.A.; Noval Rivas, M.; Paschold, L.; Willscher, E.; Binder, M.; Arditi, M.; Bahar, I. Superantigenic character of an insert unique to SARS-CoV-2 spike supported by skewed TCR repertoire in patients with hyperinflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 25254–25262.

- Cheng, M.H.; Porritt, R.A.; Rivas, M.N.; Krieger, J.M.; Ozdemir, A.B.; Garcia, G.; Arumugaswami, V.; Fries, B.C.; Arditi, M.; Bahar, I. A monoclonal antibody against staphylococcal enterotoxin B superantigen inhibits SARS-CoV-2 entry in vitro. Structure 2021, 29, 951–962.

- Arashkia, A.; Jalilvand, S.; Mohajel, N.; Afchangi, A.; Azadmanesh, K.; Salehi-Vaziri, M.; Fazlalipour, M.; Pouriayevali, M.H.; Jalali, T.; Mousavi Nasab, S.D.; et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 spike (S) protein based vaccine candidates: State of the art and future prospects. Rev. Med. Virol. 2021, 31, e2183.

- Verbeke, R.; Lentacker, I.; De Smedt, S.C.; Dewitte, H. The dawn of mRNA vaccines: The COVID-19 case. J. Control Release 2021, 333, 511–520.

- Seneff, S.; Nigh, G. Worse Than the Disease? Reviewing Some Possible Unintended Consequences of the mRNA Vaccines Against COVID-19. Int. J. Vaccine Theory Pract. Res. 2021, 2, 38–79.

- Doshi, P. Covid-19 vaccines: In the rush for regulatory approval, do we need more data? BMJ 2021, 373, n1244.

- Patterson, B.K.; Francisco, E.B.; Yogendra, R.; Long, E.; Pise, A.; Rodrigues, H. Persistence of SARS CoV-2 S1 Protein in CD16+ Monocytes in Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) Up to 15 Months Post-Infection . 2021, p. 449905. Available online: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.06.25.449905v3 (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- Golan, Y.; Prahl, M.; Cassidy, A.; Lin, C.Y.; Ahituv, N.; Flaherman, V.J.; Gaw, S.L. Evaluation of Messenger RNA From COVID-19 BTN162b2 and mRNA-1273 Vaccines in Human Milk. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, 1069–1071.

- Bansal, S.; Perincheri, S.; Fleming, T.; Poulson, C.; Tiffany, B.; Bremner, R.M. Cutting Edge: Circulating Exosomes with COVID Spike Protein Are Induced by BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) Vaccination prior to Development of Antibodies: A Novel Mechanism for Immune Activation by mRNA Vaccines. J. Immunol. 2021, 15, ji2100637.

- Ross, M.; Atalla, H.; Karrow, N.; Mallard, B.A. The bioactivity of colostrum and milk exosomes of high, average, and low immune responder cows on human intestinal epithelial cells. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 2499–2510.

- He, Y.; He, Z.; Leone, S.; Liu, S. Milk Exosomes Transfer Oligosaccharides into Macrophages to Modulate Immunity and Attenuate Adherent-Invasive E. coli (AIEC) Infection. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3198.

- Ciarambino, T.; Para, O.; Giordano, M. Immune system and COVID-19 by sex differences and age. Womens Health 2021, 17, 17455065211022262.

- Cappello, F.; Marino Gammazza, A.; Dieli, F.; Conway de Macario, E.; Macario, A.J. Does SARS-CoV-2 Trigger Stress-Induced Autoimmunity by Molecular Mimicry? A Hypothesis. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2038.

- Liu, Y.; Sawalha, A.H.; Lu, Q. COVID-19 and autoimmune diseases. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2021, 33, 155–162.

- Sacchi, M.C.; Tamiazzo, S.; Stobbione, P.; Agatea, L.; De Gaspari, P.; Stecca, A.; Lauritano, E.C.; Roveta, A.; Tozzoli, R.; Guaschino, R.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection as a trigger of autoimmune response. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2021, 14, 898–907.

- Gupta, M.; Weaver, D.F. COVID-19 as a Trigger of Brain Autoimmunity. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2021, 12, 2558–2561.

- Jacobs, J.J.L. Persistent SARS-2 infections contribute to long COVID-19. Med. Hypotheses 2021, 149, 110538.

- Zuo, Y.; Yalavarthi, S.; Navaz, S.A.; Hoy, C.K.; Harbaugh, A.; Gockman, K.; Zuo, M.; Madison, J.A.; Kanthi, Y.; Knight, J.S. Autoantibodies stabilize neutrophil extracellular traps in COVID-19. JCI Insight 2021, 6, 150111.

- Holm, S.; Kared, H.; Michelsen, A.E.; Kong, X.Y.; Dahl, T.B.; Schultz, N.H.; Nyman, T.A.; Fladeby, C.; Seljeflot, I.; Ueland, T.; et al. Immune complexes, innate immunity, and NETosis in ChAdOx1 vaccine-induced thrombocytopenia. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 18, ehab506.

- Zheng, Y.; Qin, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Li, A.; Wang, M.; Tang, Y.; Kreiswirth, B.N.; Chen, L.; Zhang, H.; et al. The tst gene associated Staphylococcus aureus pathogenicity island facilitates its pathogenesis by promoting the secretion of inflammatory cytokines and inducing immune suppression. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 138, 103797.

- Pakbaz, Z.; Sahraian, M.A.; Noorbakhsh, F.; Salami, S.A.; Pourmand, M.R. Staphylococcal enterotoxin B increased severity of experimental model of multiple sclerosis. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 142, 104064.

- Gao, S.-X.; Sun, J.; Li, H.-H.; Chen, J.; Kashif, M.R.; Zhou, P.; Wei, L.; Zheng, Q.W.; Wu, L.G.; Guan, J.C. Prenatal exposure of staphylococcal enterotoxin B attenuates the development and function of blood regulatory T cells to repeated staphylococcal enterotoxin B exposure in adult offspring rats. J. Med. Microbiol. 2020, 69, 591–599.

- Glass, R.; Norton, S.; Fox, N.; Kusnecov, A.W. Maternal immune activation with staphylococcal enterotoxin A produces unique behavioral changes in C57BL/6 mouse offspring. Brain Behav. Immun. 2019, 75, 12–25.

- Karagöz, I.K.; Munk, M.R.; Kaya, M.; Rückert, R.; Yıldırım, M.; Karabaş, L. Using bioinformatic protein sequence similarity to investigate if SARS CoV-2 infection could cause an ocular autoimmune inflammatory reactions? Exp. Eye Res. 2021, 203, 108433.

- Adiguzel, Y. Molecular mimicry between SARS-CoV-2 and human proteins. Autoimmun. Rev. 2021, 20, 102791.

- Kanduc, D.; Shoenfeld, Y. Molecular mimicry between SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein and mammalian proteomes: Implications for the vaccine. Immunol. Res. 2020, 68, 310–313.

- Martínez, Y.A.; Guo, X.; Portales-Pérez, D.P.; Rivera, G.; Castañeda-Delgado, J.E.; García-Pérez, C.A.; Enciso-Moreno, J.A.; Lara-Ramírez, E.E. The analysis on the human protein domain targets and host-like interacting motifs for the MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV/CoV-2 infers the molecular mimicry of coronavirus. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246901.

- Morsy, S.; Morsy, A. Epitope mimicry analysis of SARS-COV-2 surface proteins and human lung proteins. J. Mol. Graph Model. 2021, 105, 107836.

- Dotan, A.; Kanduc, D.; Muller, S.; Makatsariya, A.; Shoenfeld, Y. Molecular mimicry between SARS-CoV-2 and the female reproductive system. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2021.

- Vojdani, A.; Kharrazian, D. Potential antigenic cross-reactivity between SARS-CoV-2 and human tissue with a possible link to an increase in autoimmune diseases. Clin. Immunol. 2020, 217, 108480.

- Bozkurt, B.; Kamat, I.; Hotez, P.J. Myocarditis With COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines. Circulation 2021, 144, 471–484.

- Huynh, A.; Kelton, J.G.; Arnold, D.M.; Daka, M.; Nazy, I. Antibody epitopes in vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopaenia. Nature 2021, 596, 565–569.

- Greinacher, A.; Selleng, K.; Mayerle, J.; Palankar, R.; Wesche, J.; Reiche, S.; Aebischer, A.; Warkentin, T.E.; Muenchhoff, M.; Hellmuth, J.C.; et al. Anti-Platelet Factor 4 Antibodies Causing VITT do not Cross-React with SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein. Blood 2021, 138, 1269–1277.

- Arthur, J.M.; Forrest, J.C.; Boehme, K.W.; Kennedy, J.L.; Owens, S.; Herzog, C.; Liu, J.; Harville, T.O. Development of ACE2 autoantibodies after SARS-CoV-2 infection. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257016.

- Wen, J.; Cheng, Y.; Ling, R.; Dai, Y.; Huang, B.; Huang, W.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, Y. Antibody-dependent enhancement of coronavirus. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 100, 483–489.

- Ricke, D.O. Two Different Antibody-Dependent Enhancement (ADE) Risks for SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 640093.

- Rothan, H.A.; Byrareddy, S.N. The potential threat of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2021, 32, 17–22.

- Liu, Y.; Soh, W.T.; Kishikawa, J.-I.; Hirose, M.; Nakayama, E.E.; Li, S.; Sasai, M.; Suzuki, T.; Tada, A.; Arakawa, A. An infectivity-enhancing site on the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein targeted by antibodies. Cell 2021, 184, 3452–3466.e18.

- Yahi, N.; Chahinian, H.; Fantini, J. Infection-enhancing anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies recognize both the original Wuhan/D614G strain and Delta variants. A potential risk for mass vaccination? J. Infect. 2021.

- Martínez Gómez, J.M.; Ong, L.C.; Lam, J.H.; Binte Aman, S.A.; Libau, E.A.; Lee, P.X.; St. John, A.L.; Alonso, S. Maternal Antibody-Mediated Disease Enhancement in Type I Interferon-Deficient Mice Leads to Lethal Disease Associated with Liver Damage. PLoS Negl. Trop Dis. 2016, 10, e0004536.

- Lee, P.X.; Ong, L.C.; Libau, E.A.; Alonso, S. Relative Contribution of Dengue IgG Antibodies Acquired during Gestation or Breastfeeding in Mediating Dengue Disease Enhancement and Protection in Type I Interferon Receptor-Deficient Mice. PLoS Negl. Trop Dis. 2016, 10, e0004805.

- Pace, R.M.; Williams, J.E.; Järvinen, K.M.; Belfort, M.B.; Pace, C.D.W.; Lackey, K.A.; Gogel, A.C.; Nguyen-Contant, P.; Kanagaiah, P.; Fitzgerald, T.; et al. Characterization of SARS-CoV-2 RNA, Antibodies, and Neutralizing Capacity in Milk Produced by Women with COVID-19. mBio 2021, 12, e03192-20.

- Baird, J.K.; Jensen, S.M.; Urba, W.J.; Fox, B.A.; Baird, J.R. SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies Detected in Mother’s Milk Post-Vaccination. J. Hum. Lact. 2021.