| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hyun-ouk Kim | + 1886 word(s) | 1886 | 2021-10-12 07:37:32 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | Meta information modification | 1886 | 2021-10-14 04:33:21 | | |

Video Upload Options

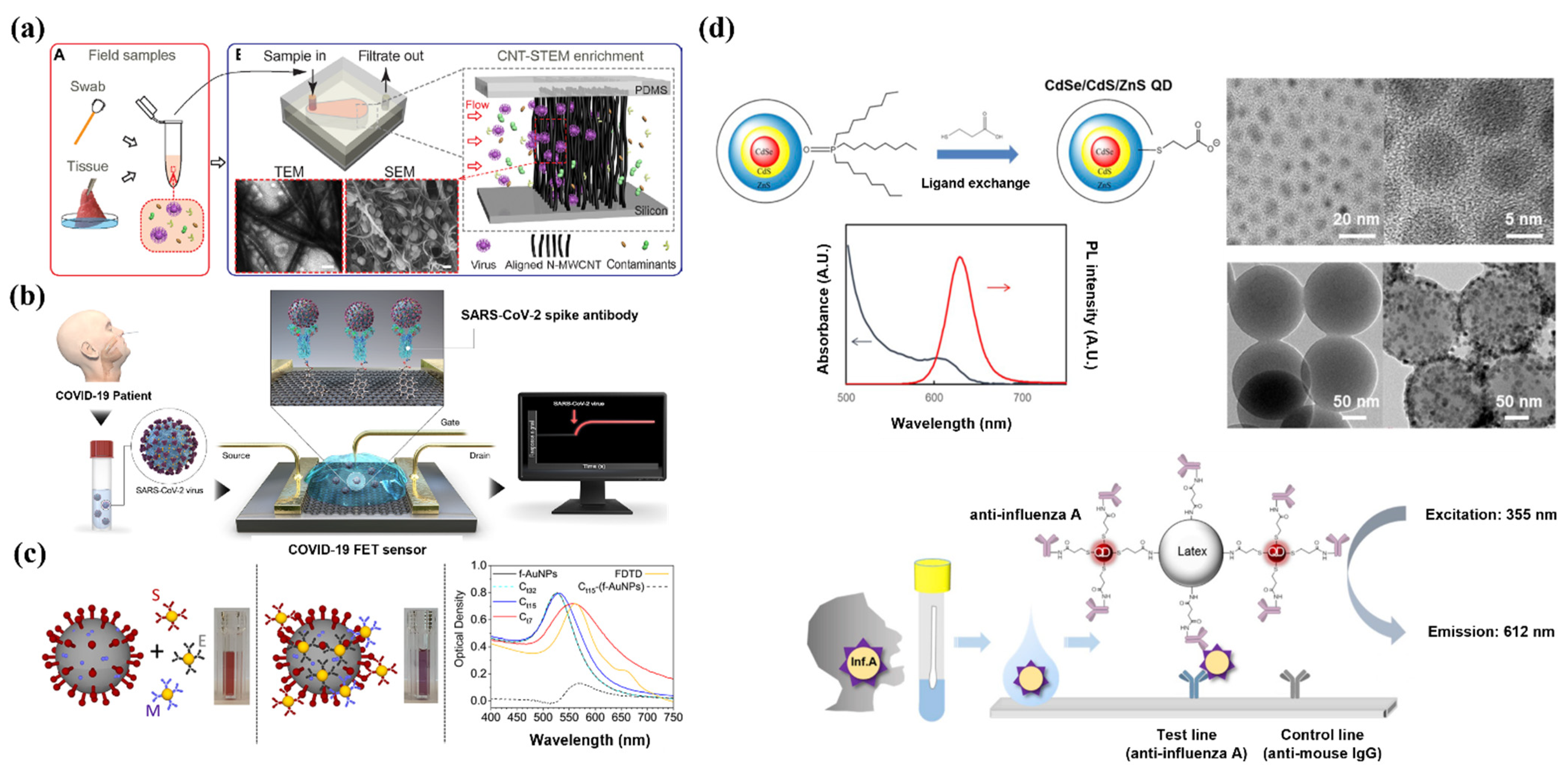

Nanomaterials can be tailored for specific uses by modulating physical and chemical properties, including size, morphology, surface charge, and solubility. Due to these controllable properties, nanomaterials have been used in biosensors to potentiate target-specific reactions that respond to biochemical environments, such as temperature, pH, and the presence of enzymes.

1. Introduction

|

Nanomaterials |

Diagnostic Techniques |

Target |

LOD |

Time |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Carbon nanotubes |

RDT |

DENV |

8.4 × 102 TCID50/mL |

>10 min |

[6] |

|

SARS-CoV-2 |

0.55 fg/mL |

>5 min |

[7] |

||

|

Immunological |

Influenza A Virus (H1N1) |

1 PFU/ml |

30 min |

[8] |

|

|

Graphene |

Immunological |

JEV/AIV |

1 fM/10 fM |

1 h |

[9] |

|

AIV |

1.6 pg/mL |

30 min |

[10] |

||

|

HIV-1 |

2.3 × 10−14 M |

1 h |

[11] |

||

|

Influenza A Virus (H5N1) |

25 PFU/mL |

15 min |

[12] |

||

|

Zika Virus |

450 pmol/L |

5 min |

[13] |

||

|

AuNPs |

Optical |

SARS-CoV-2 |

0.18 ng/μL |

>10 min |

[14] |

|

50 RNA copies per reaction |

30 min |

[15] |

|||

|

4 copies/μL |

40 min |

[16] |

|||

|

Hepatitis B virus |

100 fg/mL |

10–15 min |

[17] |

||

|

Immunological |

SARS-CoV-2 |

370 vp/mL |

15 min |

[18] |

|

|

0.08 ng/mL |

30 min |

[19] |

|||

|

Influenza A Virus |

7.8 HAU |

30 min |

[20] |

||

|

Zika Virus |

0.82 pmol/L |

50 min |

[21] |

||

|

Quantum dots |

ELISA |

Influenza A Virus |

22 pfu/mL |

>35 min |

[22] |

|

Influenza A Virus (H5N1) |

0.016 HAU |

>15 min |

[23] |

||

|

SARS-CoV-2 |

5 pg/mL |

>15 min |

[24] |

||

|

Immunological |

HEV3 |

1.23 fM |

20 min |

[25] |

|

|

SARS-CoV |

0.1 pg/mL |

1 h |

[26] |

||

|

Synthetic polymer |

Immunological |

Influenza A Virus (H1N1) |

5 × 103~104 TCID50 |

9 min |

[27] |

|

Nanofibers |

Immunological |

SARS-CoV-2 |

0.8 pg/mL |

20 min |

[28] |

2. Diagnosis

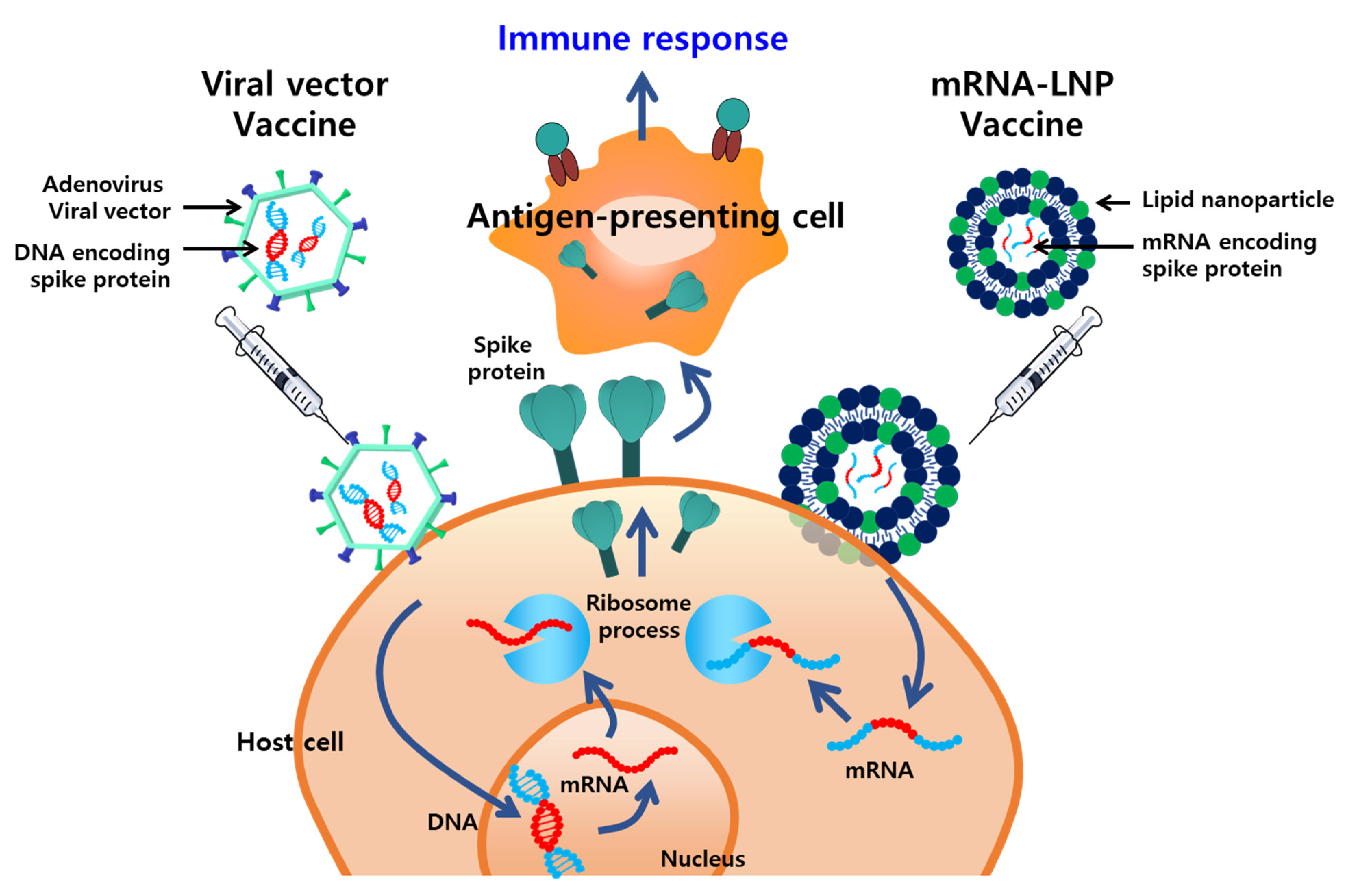

3. NP Vaccines for Emerging Viruses

4. Treatment

References

- Park, S.E. Epidemiology, virology, and clinical features of severe acute respiratory syndrome -coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2; coronavirus disease-19). Clin. Exp. Pediatr. 2020, 63, 119–124.

- Chintagunta, A.D.; Sai Krishna, M.; Nalluru, S.; Sampath Kumar, N.S. Nanotechnology: An emerging approach to combat COVID-19. Emergent Mater. 2021, 1–12.

- Díez-Pascual, A.M. Recent progress in antimicrobial nanomaterials. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2315.

- Huang, H.; Lovell, J.F. Advanced functional nanomaterials for theranostics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1603524.

- Look, M.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Blum, J.S.; Fahmy, T.M. Application of nanotechnologies for improved immune response against infectious diseases in the developing world. Adv. Drug. Deliv. Rev. 2010, 62, 378–393.

- Wasik, D.; Mulchandani, A.; Yates, M.V. A heparin-functionalized carbon nanotube-based affinity biosensor for dengue virus. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 91, 811–816.

- Shao, W.; Shurin, M.R.; Wheeler, S.E.; He, X.; Star, A. Rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2 antigens using high-purity semiconducting single-walled carbon nanotube-based field-effect transistors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 10321–10327.

- Singh, R.; Sharma, A.; Hong, S.; Jang, J. Electrical immunosensor based on dielectrophoretically-deposited carbon nanotubes for detection of influenza virus h1n1. Analyst 2014, 139, 5415–5421.

- Roberts, A.; Chauhan, N.; Islam, S.; Mahari, S.; Ghawri, B.; Gandham, R.K.; Majumdar, S.; Ghosh, A.; Gandhi, S. Graphene functionalized field-effect transistors for ultrasensitive detection of japanese encephalitis and avian influenza virus. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–12.

- Huang, J.; Xie, Z.; Xie, Z.; Luo, S.; Xie, L.; Huang, L.; Fan, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Zeng, T. Silver nanoparticles coated graphene electrochemical sensor for the ultrasensitive analysis of avian influenza virus h7. Anal. Chim. Acta 2016, 913, 121–127.

- Gong, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yang, H. A sensitive impedimetric DNA biosensor for the determination of the hiv gene based on graphene-nafion composite film. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 89, 565–569.

- Li, C.; Zou, Z.; Liu, H.; Jin, Y.; Li, G.; Yuan, C.; Xiao, Z.; Jin, M. Synthesis of polystyrene-based fluorescent quantum dots nanolabel and its performance in h5n1 virus and SARS-CoV-2 antibody sensing. Talanta 2021, 225, 122064.

- Afsahi, S.; Lerner, M.B.; Goldstein, J.M.; Lee, J.; Tang, X.; Bagarozzi, D.A., Jr.; Pan, D.; Locascio, L.; Walker, A.; Barron, F.; et al. Novel graphene-based biosensor for early detection of zika virus infection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 100, 85–88.

- Moitra, P.; Alafeef, M.; Dighe, K.; Frieman, M.B.; Pan, D. Selective naked-eye detection of SARS-CoV-2 mediated by n gene targeted antisense oligonucleotide capped plasmonic nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 7617–7627.

- Jiang, Y.; Hu, M.; Liu, A.A.; Lin, Y.; Liu, L.; Yu, B.; Zhou, X.; Pang, D.W. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 by crispr/cas12a-enhanced colorimetry. ACS Sens. 2021, 6, 1086–1093.

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, M.; Liu, C.; Chen, J.; Luo, X.; Xue, Y.; Liang, Q.; Zhou, L.; Tao, Y.; Li, M.; et al. Sensitive and rapid on-site detection of SARS-CoV-2 using a gold nanoparticle-based high-throughput platform coupled with crispr/cas12-assisted rt-lamp. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 345, 130411.

- Kim, J.; Oh, S.Y.; Shukla, S.; Hong, S.B.; Heo, N.S.; Bajpai, V.K.; Chun, H.S.; Jo, C.H.; Choi, B.G.; Huh, Y.S.; et al. Heteroassembled gold nanoparticles with sandwich-immunoassay lspr chip format for rapid and sensitive detection of hepatitis b virus surface antigen (hbsag). Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 107, 118–122.

- Huang, L.; Ding, L.; Zhou, J.; Chen, S.; Chen, F.; Zhao, C.; Xu, J.; Hu, W.; Ji, J.; Xu, H.; et al. One-step rapid quantification of SARS-CoV-2 virus particles via low-cost nanoplasmonic sensors in generic microplate reader and point-of-care device. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 171, 112685.

- Funari, R.; Chu, K.Y.; Shen, A.Q. Detection of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 spike protein by gold nanospikes in an opto-microfluidic chip. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 169, 112578.

- Liu, Y.J.; Zhang, L.Q.; Wei, W.; Zhao, H.Y.; Zhou, Z.X.; Zhang, Y.J.; Liu, S.Q. Colorimetric detection of influenza a virus using antibody-functionalized gold nanoparticles. Analyst 2015, 140, 3989–3995.

- Steinmetz, M.; Lima, D.; Viana, A.G.; Fujiwara, S.T.; Pessoa, C.A.; Etto, R.M.; Wohnrath, K. A sensitive label-free impedimetric DNA biosensor based on silsesquioxane-functionalized gold nanoparticles for zika virus detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 141, 111351.

- Bai, Z.K.; Wei, H.J.; Yang, X.S.; Zhu, Y.H.; Peng, Y.J.; Yang, J.; Wang, C.W.; Rong, Z.; Wang, S.Q. Rapid enrichment and ultrasensitive detection of influenza a virus in human specimen using magnetic quantum dot nanobeads based test strips. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 325, 128780.

- Wu, F.; Yuan, H.; Zhou, C.H.; Mao, M.; Liu, Q.; Shen, H.B.; Cen, Y.; Qin, Z.F.; Ma, L.; Li, L.S. Multiplexed detection of influenza a virus subtype h5 and h9 via quantum dot-based immunoassay. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 77, 464–470.

- Wang, C.; Yang, X.; Zheng, S.; Cheng, X.; Xiao, R.; Li, Q.; Wang, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, S. Development of an ultrasensitive fluorescent immunochromatographic assay based on multilayer quantum dot nanobead for simultaneous detection of SARS-CoV-2 antigen and influenza a virus. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 345, 130372.

- Ngo, D.B.; Chaibun, T.; Yin, L.S.; Lertanantawong, B.; Surareungchai, W. Electrochemical DNA detection of hepatitis e virus genotype 3 using pbs quantum dot labelling. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2021, 413, 1027–1037.

- Roh, C.; Jo, S.K. Quantitative and sensitive detection of sars coronavirus nucleocapsid protein using quantum dots-conjugated rna aptamer on chip. J. Chem. Technol. Biot. 2011, 86, 1475–1479.

- Son, S.U.; Seo, S.B.; Jane, S.; Choi, J.; Lim, J.W.; Lee, D.K.; Kim, H.; Seo, S.; Kang, T.; Jung, J.; et al. Naked-eye detection of pandemic influenza a (ph1n1) virus by polydiacetylene (pda)-based paper sensor as a point-of-care diagnostic platform. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 291, 257–265.

- Eissa, S.; Zourob, M. Development of a low-cost cotton-tipped electrochemical immunosensor for the detection of SARS-CoV-2. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 1826–1833.

- Yeh, Y.T.; Tang, Y.; Sebastian, A.; Dasgupta, A.; Perea-Lopez, N.; Albert, I.; Lu, H.G.; Terrones, M.; Zheng, S.Y. Tunable and label-free virus enrichment for ultrasensitive virus detection using carbon nanotube arrays. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1601026.

- Seo, G.; Lee, G.; Kim, M.J.; Baek, S.H.; Choi, M.; Ku, K.B.; Lee, C.S.; Jun, S.; Park, D.; Kim, H.G.; et al. Rapid detection of COVID-19 causative virus (SARS-CoV-2) in human nasopharyngeal swab specimens using field-effect transistor-based biosensor (vol 14, pg 5135, 2020). ACS Nano 2020, 14, 12257–12258.

- Della Ventura, B.; Cennamo, M.; Minopoli, A.; Campanile, R.; Censi, S.B.; Terracciano, D.; Portella, G.; Velotta, R. Colorimetric test for fast detection of SARS-CoV-2 in nasal and throat swabs. ACS Sens. 2020, 5, 3043–3048.

- Yezhelyev, M.V.; Gao, X.; Xing, Y.; Al-Hajj, A.; Nie, S.M.; O’Regan, R.M. Emerging use of nanoparticles in diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2006, 7, 657–667.

- Kevadiya, B.D.; Machhi, J.; Herskovitz, J.; Oleynikov, M.D.; Blomberg, W.R.; Bajwa, N.; Soni, D.; Das, S.; Hasan, M.; Patel, M.; et al. Diagnostics for SARS-CoV-2 infections. Nat. Mater. 2021, 20, 593–605.

- Hou, H.Y.; Wang, T.; Zhang, B.; Luo, Y.; Mao, L.; Wang, F.; Wu, S.J.; Sun, Z.Y. Detection of igm and igg antibodies in patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2020, 9, e1136.

- Long, Q.X.; Liu, B.Z.; Deng, H.J.; Wu, G.C.; Deng, K.; Chen, Y.K.; Liao, P.; Qiu, J.F.; Lin, Y.; Cai, X.F.; et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 845.

- Padoan, A.; Sciacovelli, L.; Basso, D.; Negrini, D.; Zuin, S.; Cosma, C.; Faggian, D.; Matricardi, P.; Plebani, M. Iga-ab response to spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19: A longitudinal study. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2020, 507, 164–166.

- Petherick, A. Developing antibody tests for SARS-CoV-2. Lancet 2020, 395, 1101–1102.

- Hildebrandt, N.; Spillmann, C.M.; Algar, W.R.; Pons, T.; Stewart, M.H.; Oh, E.; Susumu, K.; Diaz, S.A.; Delehanty, J.B.; Medintz, I.L. Energy transfer with semiconductor quantum dot bioconjugates: A versatile platform for biosensing, energy harvesting, and other developing applications. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 536–711.

- Kim, H.O.; Na, W.; Yeom, M.; Choi, J.; Kim, J.; Lim, J.W.; Yun, D.; Chun, H.; Park, G.; Park, C.; et al. Host cell mimic polymersomes for rapid detection of highly pathogenic influenza virus via a viral fusion and cell entry mechanism. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1800960.

- Farzin, L.; Shamsipur, M.; Samandari, L.; Sheibani, S. Hiv biosensors for early diagnosis of infection: The intertwine of nanotechnology with sensing strategies. Talanta 2020, 206, 120201.

- Tymm, C.; Zhou, J.H.; Tadimety, A.; Burklund, A.; Zhang, J.X.J. Scalable COVID-19 detection enabled by lab-on-chip biosensors. Cell Mol. Bioeng. 2020, 13, 313–329.

- Reed, S.G.; Orr, M.T.; Fox, C.B. Key roles of adjuvants in modern vaccines. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 1597–1608.

- Smith, D.M.; Simon, J.K.; Baker Jr, J.R. Applications of nanotechnology for immunology. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 592–605.

- Kim, M.-G.; Park, J.Y.; Shon, Y.; Kim, G.; Shim, G.; Oh, Y.-K. Nanotechnology and vaccine development. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 9, 227–235.

- van Riet, E.; Ainai, A.; Suzuki, T.; Kersten, G.; Hasegawa, H. Combatting infectious diseases; nanotechnology as a platform for rational vaccine design. Adv. Drug Deliv. 2014, 74, 28–34.

- Kim, E.; Lim, E.K.; Park, G.; Park, C.; Lim, J.W.; Lee, H.; Na, W.; Yeom, M.; Kim, J.; Song, D. Advanced nanomaterials for preparedness against (re-) emerging viral diseases. Adv. Mater. 2021, 2005927.

- Elberry, M.H.; Darwish, N.H.; Mousa, S.A. Hepatitis c virus management: Potential impact of nanotechnology. Virol. J. 2017, 14, 1–10.

- Yan, Y.; Wang, X.; Lou, P.; Hu, Z.; Qu, P.; Li, D.; Li, Q.; Xu, Y.; Niu, J.; He, Y. A nanoparticle-based hepatitis c virus vaccine with enhanced potency. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 221, 1304–1314.

- Tian, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Mao, L.; Chen, W.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, W.; Zheng, W.; Zhao, Y.; Kong, D.; et al. A peptide-based nanofibrous hydrogel as a promising DNA nanovector for optimizing the efficacy of hiv vaccine. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 1439–1445.

- Liu, Y.; Chen, C. Role of nanotechnology in hiv/aids vaccine development. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 103, 76–89.

- Shin, H.N.; Iwasaki, A. A vaccine strategy that protects against genital herpes by establishing local memory t cells. Nature 2012, 491, 463.

- Luo, M.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Cai, H.; Lu, Z.; Li, Y.; Du, M.; Huang, G.; Wang, C.; Chen, X. A sting-activating nanovaccine for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2017, 12, 648–654.

- Zhu, G.; Zhang, F.; Ni, Q.; Niu, G.; Chen, X. Efficient nanovaccine delivery in cancer immunotherapy. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 2387–2392.

- Lou, Z.Y.; Sun, Y.N.; Rao, Z.H. Current progress in antiviral strategies. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 35, 86–102.

- De Clercq, E. Antiviral agents active against influenza a viruses. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006, 5, 1015–1025.

- Riva, L.; Yuan, S.F.; Yin, X.; Martin-Sancho, L.; Matsunaga, N.; Pache, L.; Burgstaller-Muehlbacher, S.; De Jesus, P.D.; Teriete, P.; Hull, M.V.; et al. Discovery of SARS-CoV-2 antiviral drugs through large-scale compound repurposing. Nature 2020, 586, 113.

- Medhi, R.; Srinoi, P.; Ngo, N.; Tran, H.V.; Lee, T.R. Nanoparticle-based strategies to combat COVID-19. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 8557–8580.