| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rabia Ikram | + 2736 word(s) | 2736 | 2021-08-06 17:35:29 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 2736 | 2021-08-17 08:43:26 | | |

Video Upload Options

The increased production of waste materials is a significant concern due to their effect on public health and the environment. Mismanagement of food waste, in particular, has become a major global issue, thus prompting the need for better solutions that use these materials in different applications. Among various applications, food waste can be considered to be a sustainable alternative for additives in drilling fluids used in the oil and gas drilling industry. Chemical additives to drilling fluids are necessary components to facilitate drilling operations by enhancing the fluids’ properties, including rheology and filtrate loss. Studies have demonstrated that waste-derived materials, including food waste, have the potential to provide an environmentally safe alternative to toxic conventional chemical additives used in water-based drilling fluids.

1. Drilling Fluids and Rheological Properties

1.1. Mud Density or Weight

1.2. Plastic Viscosity

1.3. Yield Point

1.4. Gel Strength

1.5. Filtrate Loss and Mud Cake Thickness

2. Waste Derivatives in Drilling Fluids

2.1. Emergence of Waste Materials in the Environment

2.2. Waste Materials in Drilling Fluids

| Types of Wastes Materials | Process Parameters | Range of Particle Size | Amount of Waste Used (g) | Yield Point (lb/100 ft2) |

Plastic Viscosity (cP) | Filtrate Loss (% Reduction) |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basil Seed Powder (BSP) | 90–150 °C | 5–10 µm | 1 | 5–45 Pa | 5–28 mPa.s | 10.2–67.9% | [45] |

| Carboxymethyl cellulose carton waste (CMC) | - | - | 1–5 g | - | - | 0.4–10% | [46] |

| Wild Jujube Pit Powder (WJPP) | 6.9 MPa | 54, 75, 100 µm | - | 1.5–2.5 Pa | 3–4 mPa.s | 30–47.5% | [47] |

| Banana Peel Powder (BPP) | - | - | 6–18 g | 10–16 | 6–12 | 39–54% | [48] |

| Black Sunflower Seeds Shell Powder | 250 °F, 500 psi | 52–400 µm | 3.5–24.5 g | 26–47 | 7–13 | 0.3–25% | [33] |

| Brachystegia eurycoma rice husk | - | - | 20 | - | - | 35.62% | [49] |

| Detarium microcarpum rice husk | - | - | 15 | - | - | 44.44% | [49] |

| Fibrous Food Waste Material (FFWM) | 100 psi | 2% | - | 13 | 8 | 7.0 cc/30 min | [50] |

| Green Olive Pits’ Powder (GOPP) | - | 1.5% | 9 | 26 | 7 | 11.5 cc/30 min | [51] |

| Henna leaf extract | 78 °F, 300 °F, 100 psi | - | 10–40 | 33–52 | 23–45 | 29.9- 32% | [52] |

| Hibiscus leaf extract | 78 °F, 300 °F, 100 psi | - | 10–40 | 73–148 | 41–75 | 31.0- 35.1% | [52] |

| Palm Tree Leaves Powder (PTLP) | 55 °C | 3% | 22 | 5 | 9 | 8.9 cc/30 min | [53] |

| Potato Peels Powder (PPP) | 73 °F | 4% | 6 | 6 | 10 | 8.75 cc/30 min | [54] |

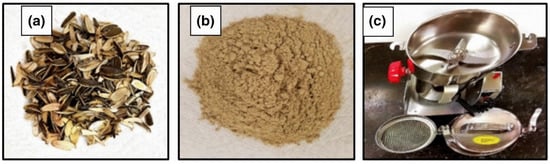

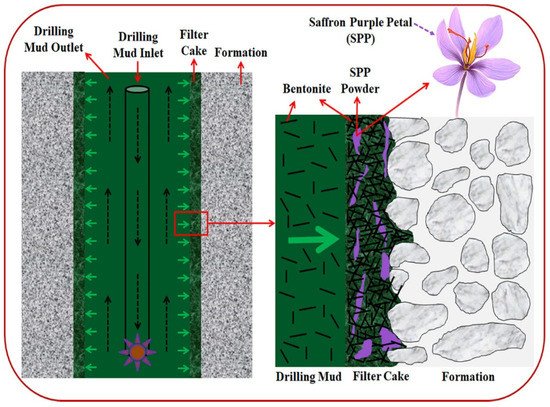

| Saffron Purple Petals (SPP) | 100 psi | - | 50 g | 6.04–10.67 Pa | 0.016–0.039 Pa.s | 23–45% | [38] |

| Durian rind | - | 44–2000 µm | 5–10 ppb | 2–75 | 10–80 | 17–60% | [55] |

| Mandarin peels powder (MPP) | - | 1–4% | - | 14–57 | 14–63 | 44.0–68.0% | [31] |

| Date Seed Powder | 100 psi | 300 µm | 0.25–2 ppb | 4 | 9 | 8–20% | [56] |

| Pistachio Shell Powder (PSP) | 104.44 °C, 3.45 MPa | 75–150 µm | 5–9 g | 12.2–13.5 | 19.8–24 | 15.3–44% | [57] |

| Soybean Peel Powder (SB) | 100 psi | - | 5 ppb | 23 | 4 | 60% | [58] |

| Grass | - | 35–300 µm | 0.25 -1 ppb | 3.5–5 | 8–9 | 11.0–14.6% | [59] |

| Corn Starch | 170–200 °F | <125 µm | 6 | - | 2.67–5 | 31% | [60] |

| Rice husk | - | 125µm | 5–20 | 9.56 Pa | 0.008 Pa.s | 16.0–42.5% | [61] |

| Agarwood | - | 45µm, 90µm | - | 22 | 11.9 | 14.0 | [62] |

| Sawdust | 70 °C | 1 mm | - | - | - | 8.6% | [63] |

| Walnut shells | - | 2–6 mm | 20–60 | 110–180 | 55–80 | 11.0–14.5% | [64] |

2.3. Bentonite in Drilling Fluids

References

- Karakosta, K.; Mitropoulos, A.C.; Kyzas, G.Z. A review in nanopolymers for drilling fluids applications. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1227, 129702.

- Werner, B.; Myrseth, V.; Saasen, A. Viscoelastic properties of drilling fluids and their influence on cuttings transport. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2017, 156, 845–851.

- Dantas, A.; Leite, R.; Nascimento, R.; Amorim, L. The influence of chemical additives in filtration control of inhibited drilling fluids. Braz. J. Pet. Gas. 2014, 8.

- Das, B.; Chatterjee, R. Wellbore stability analysis and prediction of minimum mud weight for few wells in Krishna-Godavari Basin, India. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2017, 93, 30–37.

- Ebikapaye, J. Effects of temperature on the density of water based drilling mud. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 2018, 22, 406–408.

- Ahmadi, M.A.; Shadizadeh, S.R.; Shah, K.; Bahadori, A. An accurate model to predict drilling fluid density at wellbore conditions. Egypt. J. Pet. 2018, 27, 1–10.

- Elkatatny, S. Enhancing the rheological properties of water-based drilling fluid using micronized starch. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2019, 44, 5433–5442.

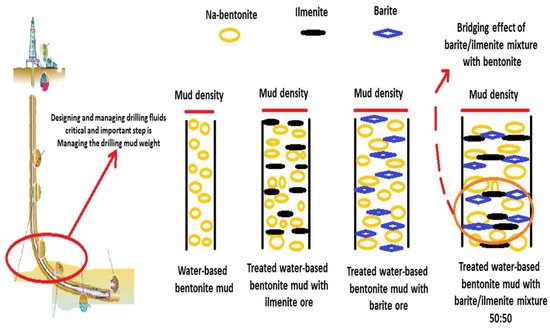

- Basfar, S.; Mohamed, A.; Elkatatny, S.; Al-Majed, A. A Combined Barite–Ilmenite Weighting Material to Prevent Barite Sag in Water-Based Drilling Fluid. Materials 2019, 12, 1945.

- Delikesheva, D.; Syzdykov, A.K.; Ismailova, J.; Kabdushev, A.; Bukayeva, G. Measurement of the Plastic Viscosity and Yield Point of Drilling Fluids. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2020, 13, 58–65.

- Maiti, M.; Ranjan, R.; Chaturvedi, E.; Bhaumik, A.K.; Mandal, A. Formulation and characterization of water-based drilling fluids for gas hydrate reservoirs with efficient inhibition properties. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2021, 42, 338–351.

- Alakbari, F.; Elkatatny, S.; Kamal, M.S.; Mahmoud, M. Optimizing the gel strength of water-based drilling fluid using clays for drilling horizontal and multi-lateral wells. In SPE Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Annual Technical Symposium and Exhibition; OnePetro: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2018.

- Mohamed, A.; Al-Afnan, S.; Elkatatny, S.; Hussein, I. Prevention of barite sag in water-based drilling fluids by a urea-based additive for drilling deep formations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2719.

- Novriansyah, A. Experimental analysis of cassava starch as a fluid loss control agent on drilling mud. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 39, 1094–1098.

- Dejtaradon, P.; Hamidi, H.; Chuks, M.H.; Wilkinson, D.; Rafati, R. Impact of ZnO and CuO nanoparticles on the rheological and filtration properties of water-based drilling fluid. Colloids Surf. A 2019, 570, 354–367.

- Ali, M.; Jarni, H.H.; Aftab, A.; Ismail, A.R.; Saady, N.M.C.; Sahito, M.F.; Keshavarz, A.; Iglauer, S.; Sarmadivaleh, M. Nanomaterial-based drilling fluids for exploitation of unconventional reservoirs: A review. Energies 2020, 13, 3417.

- Bologna, M.; Aquino, G. Deforestation and world population sustainability: A quantitative analysis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7631.

- Rautela, R.; Arya, S.; Vishwakarma, S.; Lee, J.; Kim, K.-H.; Kumar, S. E-waste management and its effects on the environment and human health. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 773, 145623.

- Castillo-Giménez, J.; Montañés, A.; Picazo-Tadeo, A.J. Performance and convergence in municipal waste treatment in the European Union. Waste Manag. 2019, 85, 222–231.

- Hoornweg, D.; Bhada-Tata, P. What a Waste: A Global Review of Solid Waste Management. 2012. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/17388 (accessed on 1 March 2012).

- Hoornweg, D.; Bhada-Tata, P.; Kennedy, C. Environment: Waste production must peak this century. Nat. News 2013, 502, 615.

- Demirbas, A. Waste management, waste resource facilities and waste conversion processes. Energy Convers. Manag. 2011, 52, 1280–1287.

- Khatib, I.A. Municipal solid waste management in developing countries: Future challenges and possible opportunities. Integr. Waste Manag. 2011, 2, 35–48.

- Gaur, V.K.; Sharma, P.; Sirohi, R.; Awasthi, M.K.; Dussap, C.-G.; Pandey, A. Assessing the impact of industrial waste on environment and mitigation strategies: A comprehensive review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 398, 123019.

- Kumar, U.; Goonetilleke, D.; Gaikwad, V.; Pramudita, J.C.; Joshi, R.K.; Sharma, N.; Sahajwalla, V. Activated carbon from e-waste plastics as a promising anode for sodium-ion batteries. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 10310–10322.

- Suchorab, Z.; Franus, M.; Barnat-Hunek, D. Properties of Fibrous Concrete Made with Plastic Optical Fibers from E-Waste. Materials 2020, 13, 2414.

- Prochon, M.; Marzec, A.; Dzeikala, O. Hazardous Waste Management of Buffing Dust Collagen. Materials 2020, 13, 1498.

- Tanskanen, P. Management and recycling of electronic waste. Acta Mater. 2013, 61, 1001–1011.

- Yan, N.; Chen, X. Sustainability: Don’t waste seafood waste. Nat. News 2015, 524, 155.

- Huang, Y.; Mei, L.; Chen, X.; Wang, Q. Recent developments in food packaging based on nanomaterials. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 830.

- Dankwa, O.; Ackumey, S.; Amorin, R. Investigating the potential use of waste vegetable oils to produce synthetic base fluids for drilling mud formulation. In SPE Nigeria Annual International Conference and Exhibition; OnePetro: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2018.

- Al-Hameedi, A.T.T.; Alkinani, H.H.; Dunn-Norman, S.; Al-Alwani, M.A.; Alshammari, A.F.; Alkhamis, M.M.; Mutar, R.A.; Al-Bazzaz, W.H. Experimental investigation of environmentally friendly drilling fluid additives (mandarin peels powder) to substitute the conventional chemicals used in water-based drilling fluid. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2020, 10, 407–417.

- Al-Hameedi, A.T.T.; Alkinani, H.H.; Dunn-Norman, S.; Al-Alwani, M.A.; Alshammari, A.F.; Albazzaz, H.W.; Alkhamis, M.M.; Alashwak, N.F.; Mutar, R.A. Insights into the application of new eco-friendly drilling fluid additive to improve the fluid properties in water-based drilling fluid systems. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 183, 106424.

- Al-Hameedi, A.T.T.; Alkinani, H.H.; Alkhamis, M.M.; Dunn-Norman, S. Utilizing a new eco-friendly drilling mud additive generated from wastes to minimize the use of the conventional chemical additives. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2020, 10, 3467–3481.

- Bayat, A.E.; Moghanloo, P.J.; Piroozian, A.; Rafati, R. Experimental investigation of rheological and filtration properties of water-based drilling fluids in presence of various nanoparticles. Colloids Surf. A 2018, 555, 256–263.

- Fazelabdolabadi, B.; Khodadadi, A.A.; Sedaghatzadeh, M. Thermal and rheological properties improvement of drilling fluids using functionalized carbon nanotubes. Appl. Nanosci. 2015, 5, 651–659.

- Hassani, S.; Vu, T.N.; Rosli, N.R.; Esmaeely, S.N.; Choi, Y.-S.; Young, D.; Nesic, S. Wellbore integrity and corrosion of low alloy and stainless steels in high pressure CO2 geologic storage environments: An experimental study. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 2014, 23, 30–43.

- Li, X.; Jiang, G.; Shen, X.; Li, G. Poly-L-arginine as a high-performance and biodegradable shale inhibitor in water-based drilling fluids for stabilizing wellbore. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 1899–1907.

- Ghaderi, S.; Haddadi, S.A.; Davoodi, S.; Arjmand, M. Application of sustainable saffron purple petals as an eco-friendly green additive for drilling fluids: A rheological, filtration, morphological, and corrosion inhibition study. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 315, 113707.

- da Silva, Í.G.; Lucas, E.F.; Advincula, R. On the use of an agro waste, Miscanthus x. Giganteus, as filtrate reducer for water-based drilling fluids. J. Disper. Sci. Technol. 2020, 1–10.

- Joshi, P.; Goyal, S.; Singh, R.; Thakur, K. Development of water based drilling fluid using tamarind seed powder. Mater. Today Proc. 2021.

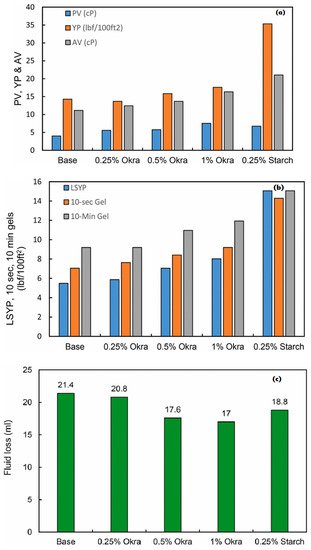

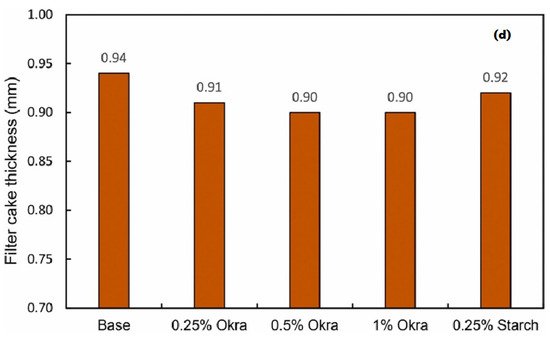

- Murtaza, M.; Tariq, Z.; Zhou, X.; Al-Shehri, D.; Mahmoud, M.; Kamal, M.S. Okra as an environment-friendly fluid loss control additive for drilling fluids: Experimental & modeling studies. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 204, 108743.

- Wiśniowski, R.; Skrzypaszek, K.; Małachowski, T. Selection of a Suitable Rheological Model for Drilling Fluid Using Applied Numerical Methods. Energies 2020, 13, 3192.

- Magzoub, M.I.; Ibrahim, M.H.; Nasser, M.S.; El-Naas, M.H.; Amani, M. Utilization of Steel-Making Dust in Drilling Fluids Formulations. Processes 2020, 8, 538.

- Haile, A.; Gelebo, G.G.; Tesfaye, T.; Mengie, W.; Mebrate, M.A.; Abuhay, A.; Limeneh, D.Y. Pulp and paper mill wastes: Utilizations and prospects for high value-added biomaterials. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2021, 8, 35.

- Zhong, H.; Gao, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, A.; Qiu, Z.; Kong, X.; Huang, W. Minimizing the filtration loss of water-based drilling fluid with sustainable basil seed powder. Petroleum 2021.

- Rita, N.; Khalid, I.; Efras, M.R. Drilling mud performances consist of CMC made by carton waste and Na2CO3 for reducing lost circulation. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 39, 1099–1102.

- Zhou, G.; Qiu, Z.; Zhong, H.; Zhao, X.; Kong, X. Study of Environmentally Friendly Wild Jujube Pit Powder as a Water-Based Drilling Fluid Additive. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 1436–1444.

- Al-Hameedi, A.T.T.; Alkinani, H.H.; Dunn-Norman, S.; Salem, E.; Knickerbocker, M.D.; Alashwak, N.F.; Mutar, R.A.; Al-Bazzaz, W.H. Laboratory Study of Environmentally Friendly Drilling Fluid Additives Banana Peel Powder for Modifying the Drilling Fluid Characteristics in Water-Based Muds. In International Petroleum Technology Conference; OnePetro: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2020.

- Okon, A.N.; Akpabio, J.U.; Tugwell, K.W. Evaluating the locally sourced materials as fluid loss control additives in water-based drilling fluid. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04091.

- Al-Hameedi, A.T.T.; Alkinani, H.H.; Dunn-Norman, S.; Alashwak, N.A.; Alshammari, A.F.; Alkhamis, M.M.; Mutar, R.A.; Ashammarey, A. Evaluation of environmentally friendly drilling fluid additives in water-based drilling mud. In SPE Europec Featured at 81st EAGE Conference and Exhibition; OnePetro: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2019.

- Al-Hameedi, A.T.T.; Alkinani, H.H.; Dunn-Norman, S.; Alkhamis, M.M.; Feliz, J.D. Full-set measurements dataset for a water-based drilling fluid utilizing biodegradable environmentally friendly drilling fluid additives generated from waste. Data Brief 2020, 28, 104945.

- Ismail, A.R.; Mohd, N.M.; Basir, N.F.; Oseh, J.O.; Ismail, I.; Blkoor, S.O. Improvement of rheological and filtration characteristics of water-based drilling fluids using naturally derived henna leaf and hibiscus leaf extracts. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2020, 10, 3541–3556.

- Al-Hameedi, A.T.T.; Alkinani, H.H.; Dunn-Norman, S.; Al-Alwani, M.A.; Al-Bazzaz, W.H.; Alshammari, A.F.; Albazzaz, H.W.; Mutar, R.A. Experimental investigation of bio-enhancer drilling fluid additive: Can palm tree leaves be utilized as a supportive eco-friendly additive in water-based drilling fluid system? J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2020, 10, 595–603.

- Al-Hameedi, A.T.T.; Alkinani, H.H.; Dunn-Norman, S.; Alashwak, N.A.; Alshammari, A.F.; Alkhamis, M.M.; W Albazzaz, H.; Mutar, R.A.; Alsaba, M.T. Environmental friendly drilling fluid additives: Can food waste products be used as thinners and fluid loss control agents for drilling fluid? In SPE Symposium: Asia Pacific Health, Safety, Security, Environment and Social Responsibility; OnePetro: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2019.

- Majid, N.F.F.; Katende, A.; Ismail, I.; Sagala, F.; Sharif, N.M.; Yunus, M.A.C. A comprehensive investigation on the performance of durian rind as a lost circulation material in water based drilling mud. Petroleum 2019, 5, 285–294.

- Wajheeuddin, M.; Hossain, M.E. Development of an environmentally-friendly water-based mud system using natural materials. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2018, 43, 2501–2513.

- Davoodi, S.; SA, A.R.; Jamshidi, S.; Jahromi, A.F. A novel field applicable mud formula with enhanced fluid loss properties in high pressure-high temperature well condition containing pistachio shell powder. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2018, 162, 378–385.

- Al-Saba, M.; Amadi, K.; Al-Hadramy, K.; Al Dushaishi, M.; Al-Hameedi, A.; Alkinani, H. Experimental investigation of bio-degradable environmental friendly drilling fluid additives generated from waste. In SPE International Conference and Exhibition on Health, Safety, Security, Environment, and Social Responsibility; OnePetro: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2018.

- Hossain, M.E.; Wajheeuddin, M. The use of grass as an environmentally friendly additive in water-based drilling fluids. Pet. Sci. 2016, 13, 292–303.

- Ghazali, N.A.; Mohd, T.A.T.; Alias, N.H.; Azizi, A.; Harun, A.A. The Effect of Lemongrass as Lost Circulation Material (LCM) to the Filtrate and Filter Cake Formation; Trans Tech Publications Ltd.: Stafa-Zurich, Switzerland, 2014.

- Okon, A.N.; Udoh, F.D.; Bassey, P.G. Evaluation of rice husk as fluid loss control additive in water-based drilling mud. In SPE Nigeria Annual International Conference and Exhibition; OnePetro: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2014.

- Azizi, A.; Ibrahim, M.S.N.; Hamid, K.H.K.; Sauki, A.; Ghazali, N.A.; Mohd, T.A.T. Agarwood waste as a new fluid loss control agent in water-based drilling fluid. Int. J. Sci. Eng. 2013, 5, 101–105.

- Adebayo, T.A.; Chinonyere, P.C. Sawdust as a filtration control and density additives in water-based drilling mud. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2012, 3, 1–2.

- Iscan, A.; Kok, M. Effects of walnut shells on the rheological properties of water-based drilling fluids. Energy Sources Part A 2007, 29, 1061–1068.

- Alcheikh, I.; Ghosh, B. A comprehensive review on the advancement of non-damaging drilling fluids. Int. J. Petrochem. Res. 2017, 1, 61–72.

- Li, M.-C.; Wu, Q.; Lei, T.; Mei, C.; Xu, X.; Lee, S.; Gwon, J. Thermothickening Drilling Fluids Containing Bentonite and Dual-Functionalized Cellulose Nanocrystals. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 8206–8215.

- da Câmara, P.C.; Madruga, L.Y.; Marques, N.d.N.; Balaban, R.C. Evaluation of polymer/bentonite synergy on the properties of aqueous drilling fluids for high-temperature and high-pressure oil wells. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 327, 114808.

- Dong, W.; Pu, X.; Ren, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Gao, F.; Xie, W. Thermoresponsive bentonite for water-based drilling fluids. Materials 2019, 12, 2115.

- Abdou, M.; Al-Sabagh, A.; Ahmed, H.E.-S.; Fadl, A. Impact of barite and ilmenite mixture on enhancing the drilling mud weight. Egypt. J. Pet. 2018, 27, 955–967.

- Magzoub, M.; Mahmoud, M.; Nasser, M.; Hussein, I.; Elkatatny, S.; Sultan, A. Thermochemical upgrading of calcium bentonite for drilling fluid applications. J. Energy Res. Technol. 2019, 141, 042902.

- Karagüzel, C.; Çetinel, T.; Boylu, F.; Cinku, K.; Çelik, M. Activation of (Na, Ca)-bentonites with soda and MgO and their utilization as drilling mud. Appl. Clay Sci. 2010, 48, 398–404.

- Li, M.-C.; Wu, Q.; Han, J.; Mei, C.; Lei, T.; Lee, S.-Y.; Gwon, J. Overcoming Salt Contamination of Bentonite Water-Based Drilling Fluids with Blended Dual-Functionalized Cellulose Nanocrystals. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 11569–11578.

- Xie, B.; Tchameni, A.P.; Luo, M.; Wen, J. A novel thermo-associating polymer as rheological control additive for bentonite drilling fluid in deep offshore drilling. Mater. Lett. 2021, 284, 128914.