Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Oxana Galzitskaya | + 2135 word(s) | 2135 | 2021-07-15 09:43:20 |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Galzitskaya, O.; Grishin, S. Amyloidogenic Regions in bPaS1. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/12241 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Galzitskaya O, Grishin S. Amyloidogenic Regions in bPaS1. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/12241. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Galzitskaya, Oxana, Sergei Grishin. "Amyloidogenic Regions in bPaS1" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/12241 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Galzitskaya, O., & Grishin, S. (2021, July 20). Amyloidogenic Regions in bPaS1. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/12241

Galzitskaya, Oxana and Sergei Grishin. "Amyloidogenic Regions in bPaS1." Encyclopedia. Web. 20 July, 2021.

Copy Citation

Bacterial S1 protein is a functionally important ribosomal protein. It is a part of the 30S ribosomal subunit and is also able to interact with mRNA and tmRNA. An important feature of the S1 protein family is a strong tendency towards aggregation.

ribosomal S1 proteins

amyloidogenic regions

toxicity

antibacterial peptides

amyloid

mass spectrometry

1. Introduction

The study of amyloids as ordered fibrillar protein aggregates is of great importance for elucidating their role in human pathologies, especially in neurodegenerative diseases [1][2][3]. It is known that, under certain conditions, most proteins and peptides tend not only to aggregation, but also to form amyloid-like fibrils [4][5][6]; in a particular case, the formation of amyloids of some proteins can be induced by other amyloidogenic proteins and peptides [7][8]. Currently, interest in the study of amyloids is also associated with the fact that they can be used in various nano- and bio-technological developments, including as antimicrobial agents against pathogenic microorganisms [9][10][11]. In recent reviews of scientific articles, the prospects of using antimicrobial peptides in medicine are discussed [12][13], including those acting by the mechanism of directed coaggregation with the target protein due to the interaction of amyloidogenic sites that constitute the spine of amyloid fibrils [14]. Disruption of the native structure of the most important bacterial proteins, in particular ribosomal ones, caused by directed aggregation, can be accompanied by a loss of the functional activity of the protein, which, in turn, can lead to a change in normal cellular metabolism and the death of bacteria.

The ribosomal S1 protein is the largest bacterial protein of the 30S ribosomal subunit and can perform, in addition to structural, many other functions, interacting with both RNA and other proteins [15][16][17][18]. It was shown that amber mutation and knockout of the gene encoding the bS1 protein lead to the death of bacterial cells [19][20]. The bS1 protein, which is present only in bacterial cells, contains, depending on the taxonomic affiliation of the microorganism, from one to six domains of the S1 protein (D1–D6), separated by flexible regions [21][22]. It is important that the S1 domain is a structural variant of the oligosaccharide/oligonucleotide-binding fold (OB-fold) [23][24] and can exhibit amyloidogenic properties, like another analog of the OB-fold, the cold shock domain [25]. Previously, peptides with amyloidogenic properties and antimicrobial activity against Thermus thermophilus were synthesized and studied based on the sequences of the S1 domains of the ribosomal S1 protein of the model organism T. thermophilus [26].

P. aeruginosa is a pathogenic bacterium that can cause nosocomial infections [27][28], and for which cases of multiple antibiotic resistance are increasingly being reported [29][30]. Recently, antimicrobial peptides have been considered as an alternative to classical antibiotics for the treatment of diseases caused by multidrug-resistant strains of P. aeruginosa [31][32][33]. Information about the amyloidogenic regions in the structure of the ribosomal S1 protein from P. aeruginosa (bPaS1) will allow the development of new antimicrobial peptides that specifically interact with this target protein and cause its aggregation, which will ultimately lead to disruption of the functioning of the ribosomal S1 protein and suppress the vital activity of this pathogenic bacteria.

The main contribution to the formation of amyloids is made by amino acid residues, which contribute to a denser packing of the protein structure [34][35]. Consequently, protein regions included in the spine of amyloid fibrils are characterized by high resistance to protease treatment, which is used to determine amyloidogenic regions in products of limited proteolysis of aggregates [36][37].

In the present work, amyloidogenic fragments were identified in the amino acid sequence of bPaS1, using the programs for searching and predicting amyloidogenic regions FoldAmyloid [38], Waltz [39], Pasta 2.0 [40] and AGGRESCAN [41], and experimentally by analyzing the products of limited proteolysis of bPaS1 aggregates using high performance liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry (LC-MS). The tendency to amyloid formation of peptides synthesized on the basis of amyloidogenic regions of bPaS1 was studied by electron microscopy (EM) and fluorescence spectroscopy (using thioflavin T (ThT)), which are widely used to detect amyloids [42][43][44].

2. Isolation and Purification of bPaS1

The E. coli strain was obtained, the genetic construct allows us to obtain the recombinant bPaS1 with additional inserts: an N-terminal sequence with 6 His, which allows the use of affinity chromatography purification; a specific TEV protease recognition site for cleaving intact bPaS1. Nucleic acids were precipitated with streptomycin sulfate and the precipitates were removed from protein samples. The degree of purification of bPaS1 preparations was assessed by electrophoresis of samples under denaturing conditions. The resulting final preparation had a purity of at least 90%.

3. Prediction and Experimental Determination of bPaS1 Regions Prone to Aggregation

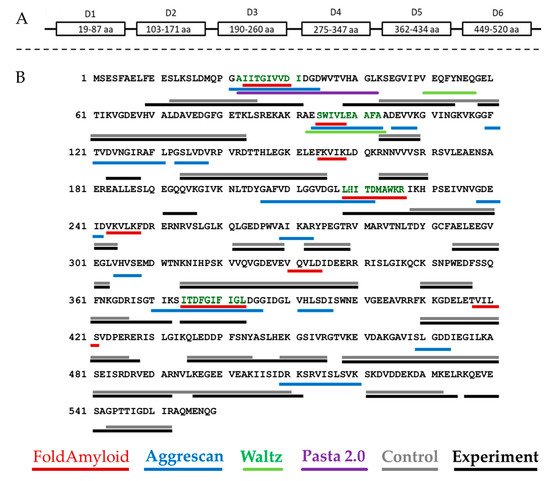

The ability of a protein to aggregate and form amyloid-like fibrils is primarily determined by the presence of amyloidogenic regions in its structure, which can be predicted using special programs developed for this purpose. Prediction of amyloidogenic sites for bPaS1 was performed using four programs: FoldAmyloid, Waltz, AGGRESCAN, and Pasta 2.0 (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the domain organization of bPaS1 (A) and comparison of predicting amyloidogenic regions using programs with the results of peptide coverage after LC-MS analysis of hydrolysates of control and experimental (aggregate) protein preparations (B). The peptides identified in the control and experimental samples, respectively, are underlined in gray and black. The bPaS1 sequence is taken from the UniProt database (UniProt. Available online: https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q9HZ71 (accessed on 20 January 2021)). The regions of bPaS1, prototype peptide synthesis, are shown black–green color.

Each program predicts at least one region prone to amyloid formation in the bPaS1 sequence. However, the prediction results differ between different programs as they use different algorithms to find amyloidogenic regions. Subsequently, an experimental search for protein regions resistant to the action of proteases was carried out in the course of limited proteolysis and analysis of hydrolysates by LC-MS. In total, 146 significant peptides were found in the products of limited proteolysis of bPaS1 aggregates. At the same time, only 96 significant peptides were detected in the control sample without incubation for aggregation. Subsequently, significant peptides identified in the hydrolysates of control and experimental bPaS1 samples were ranked by length, the longest of them was compared with the bPaS1 sequence in order to determine the regions most protected from the action of proteases in aggregates and control preparations (Figure 1).

As shown in Figure 1B, the overall peptide coverage for protein aggregate hydrolysates and controls is similar. At the same time, additional amino acid sequences for aggregates have been identified that may play a role in the formation of associates. LC-MS data were analyzed, and peptides with a length of at least five amino acid residues were selected (similar to the selection criterion in programs predicting amyloidogenic sequences of at least five amino acid residues), which are present only in hydrolysates of aggregates and are not observed in control samples (Table 1).

Table 1. Unique peptides identified as a result of comparing data from LC-MS analysis of hydrolysates of bPaS1 aggregates.

| Peptide | Prediction of Amyloidogenicity | Percentage of Most Non-Polar a.a. [45] (V,I,F,C,L,A,M), % | Observed Mass, Da | Theoretical Mass, Da | Measurement Error, ppm * | Molecular Ion, m/z | Charge (z) | Value of the Function T ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEESLK (9–14 a.a.) |

No | 0 | 751.376 | 751.3752 | 0.5 | 376.6951 | +2 | 35.71 |

| AIITGIVVDI (22–31 a.a.) | AGGRESCAN, Pasta 2.0, partially FoldAmyloid (23–30 a.a.) |

70 | 1012.618 | 1012.6168 | 0.9 | 507.3162 | +2 | 41.51 |

| VHAGLK (38–43 a.a.) |

Pasta 2.0 | 50 | 623.374 | 623.3755 | –1.8 | 312.6945 | +2 | 17.19 |

| DVNGIR (123–128 a.a.) |

AGGRESCAN | 33 | 672.356 | 672.3555 | 0.7 | 337.1852 | +2 | 32 |

| E (+27.99) GQQVK *** (191–196 a.a.) | No | 17 | 715.35 | 715.35 | –0.3 | 358.6822 | +2 | 16.8 |

| LHITDMAWKR (218–227 a.a.) | FoldAmyloid, partially AGGRESCAN (218–223 a.a.) |

40 | 1269.666 | 1269.6652 | 0.4 | 635.8401 | +2 | 114.36 |

| ISGTIK (367–372 a.a.) |

partially AGGRESCAN (370–372 a.a.) |

33 | 617.375 | 617.3748 | 0.7 | 309.6949 | +2 | 27.5 |

| ITDFGIFIGL (374–383 a.a.) | AGGRESCAN, partially FoldAmyloid (375–382 a.a.) |

60 | 1094.601 | 1094.6012 | –0.1 | 548.3078 | +2 | 76.43 |

| ASLHEK (445–450 a.a.) |

No | 33 | 683.361 | 683.3602 | 1 | 342.6877 | +2 | 30.93 |

| KQEVESA (536–542 a.a.) |

No | 29 | 789.388 | 789.3868 | 1.1 | 395.7011 | +2 | 41.89 |

*—The accuracy of molecular weight measurement of 1 ppm (parts per million) corresponds to 0.001 Da for an ion with a molecular weight of 1000 Da. **—For the PEAKS Studio 7.5 software we used (Bioinformatics Solution Inc., Waterloo, ON N2L 6J2, Canada) the value of the function T = –10 lgP, where P is the probability that a false identification of a peptide in the current search will achieve the same or better conformity score. For peptide mapping, only peptides for which a T value > 15 were used, which corresponds to the p-criterion < 0.03 [46]. ***—Mass shift (+27.99) means amino acid post-isolation modification (formylation) at the N-termini for peptide EGQQVK.

As follows from Table 1, the results of bioinformatic analysis and experimental determination of amyloidogenic regions in the bPaS1 sequence do not coincide for all protease-resistant peptides found in protein aggregates. At the same time, for the identified peptides FEESLK, AIITGIVVDI, DVNGIR, LHITDMAWKR, ITDFGIFIGL, ASLHEK, KQEVESA, the accuracy of molecular weight measurement was no worse than 1.8 ppm, and the T function value was at least two times higher than the threshold value, which on the whole indicates a high reliability of the experimental determination. Thus, the bPaS1 regions that overlap with the results of predicting amyloidogenicity by at least two programs, or are identified only in the products of limited proteolysis of bPaS1 aggregates, were used as prototypes for the synthesis of peptides: AIITGIVVDI, SWIVLEAAFA, ITDFGIFIGL and LHITDMAWKR (Figure 1B). Interestingly, the local distribution of non-polar amino acid residues, especially V, I, F, C, can be used to assess the propensity of a peptide to form amyloid structures [45]. The AIITGIVVDI, SWIVLEAAFA, ITDFGIFIGL fragments are characterized by a high percentage of nonpolar amino acid residues (70%, 70%, and 60%, respectively), in contrast to the LHITDMAWKR peptide (40%).

The bPaS1 regions, which are theoretically predicted to be amyloidogenic and experimentally resistant to the action of proteases, are of interest for further study and discussion of the prospects for using antimicrobial peptides acting on the basis of directed coaggregation in the development of antimicrobial peptides.

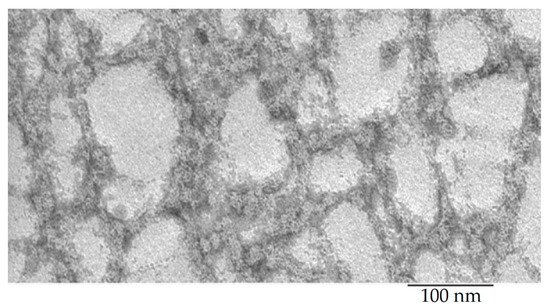

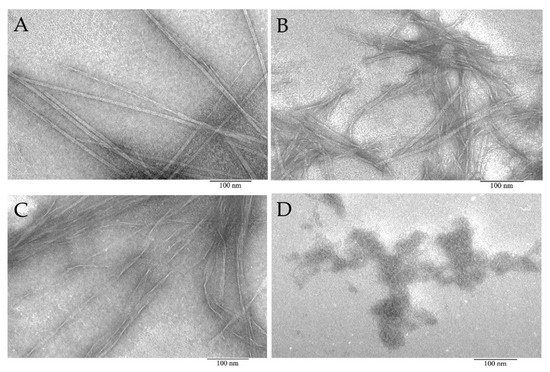

4. Electron Microscopic Images of Aggregates

Recombinant bPaS1 was isolated, purified and analyzed using the EM method. According to EM data (Figure 2), bPaS1 under conditions of 50 mM TrisHCl, pH 8.0; 100 mM NaCl; 10 mM MgCl2; 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol forms disordered aggregates. That is, as in the case of the recombinant protein bS1 from T. thermophilus [47], bPaS1 does not form fibrils. However, it should be noted that bPaS1, in contrast to the previously studied bS1 from T. thermophilus, is less prone to aggregation and forms small and less dense aggregates of various sizes [47]. The images of amyloids/aggregates of peptide synthesized based on the predicted amyloidogenic regions in the bPaS1 amino acid sequence are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2. Electron microscopic image of the bPaS1 protein under conditions of 50 mM TrisHCl, pH 8.0; 100 mM NaCl; 10 mM MgCl2; 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol.

Figure 3. Electron microscopic images of aggregates formed from peptide preparations synthesized based on the bPaS1 sequence: AIITGIVVDI (A), SWIVLEAAFA (B), ITDFGIFIGL (C), and disordered aggregates of the LHITDMAWKR peptide (D).

According to EM data, it was shown that the AIITGIVVDI, SWIVLEAAFA, and ITDFGIFIGL peptides under conditions of 50 mM TrisHCl, pH 7.5; 150 mM NaCl, incubation for 5 h at 37 °C are able to form amyloid-like fibrils of various morphologies. Under the same conditions, the LHITDMAWKR peptide did not form fibrils, but only disordered aggregates.

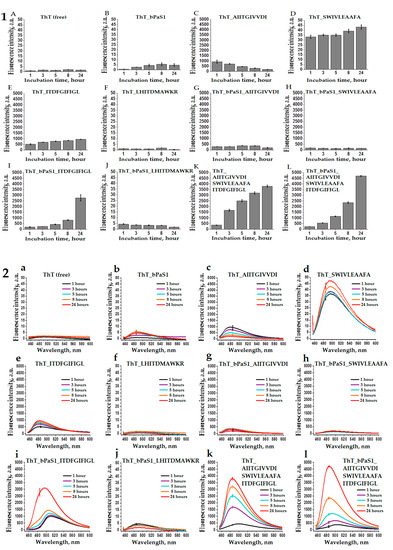

5. Thioflavin T Fluorescence Assay for Aggregation of bPaS1 and Peptides

The property of thioflavin T to bind to amyloid fibrils with a simultaneous multiple increase in fluorescence at a wavelength of ~485 nm [48] was used by us to analyze the tendency towards the formation of amyloids in bPaS1 preparations and AIITGIVVDI, SWIVLEAAFA, ITDFGIFIGL, LHITDMAWKR peptides (Figure 4). In Figure 4 (Part 1), the ThT fluorescence intensity at a wavelength of ~485 nm, exceeding the control values for free ThT by a factor of ten or more, was obtained for preparations of the AIITGIVVDI, SWIVLEAAFA, ITDFGIFIGL peptides (Figure 4C–E,K, Part 1), as well as in a mixture of these peptides with bPaS1 (Figure 4G–I,L, Part 1). At the same time, for bPaS1 preparations and the LHITDMAWKR peptide (Figure 4B,F, Part 1), as well as for their mixture in solution (Figure 4J, Part 1), a multiple increase in the ThT fluorescence intensity was not observed.

Figure 4. Histograms (1) and spectra (2) of fluorescence intensity of free thioflavin T (A,a) and in solution with bPaS1 (B,b), individual peptides AIITGIVVDI (C,c), SWIVLEAAFA (D,d), ITDFGIFIGL (E,e), LHITDMAWKR (F,f), a mixture of peptides (K,k), as well as in mixtures of bPaS1 with peptides (G,g), (H,h), (I,i), (J,j), (L,l). Error bars with standard deviations for the mean values of the measured fluorescence intensity after 1, 3, 5, 8, and 24 h of incubation are shown.

Thus, the presence of the effect of a multiple increase in the ThT fluorescence intensity upon incubation with preparations of the AIITGIVVDI, SWIVLEAAFA, ITDFGIFIGL peptides and the absence of such an effect for preparations with the LHITDMAWKR peptide is consistent with the data of electron microscopy that the AIITGIVVDI, SWIVLEAAFA, ITDFGIFIGL peptides form amyloid fibrils, while only disordered aggregates of the peptide are found in the LHITDMAWKR preparations.

It should be noted that when testing the propensity for coaggregation of individual peptides with bPaS1, the greatest increase in the ThT fluorescence intensity was observed in a mixture of the ITDFGIFIGL peptide with bPaS1 after 24 h of incubation (Figure 4i, Part 2).

Thus, although bPaS1 preparations do not form amyloid-like fibrils, they affect the change in the relative intensity and wavelength of the maximum intensity of ThT fluorescence in mixtures with amyloidogenic peptides. No such effects were observed in mixtures of bPaS1 with the non-amyloidogenic LHITDMAWKR peptide.

References

- A. A. Nizhnikov; K. S. Antonets; S. G. Inge-Vechtomov; Amyloids: from pathogenesis to function. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2015, 80, 1127-1144, 10.1134/s0006297915090047.

- Y. Y. Stroylova; G. G. Kiselev; E. V. Schmalhausen; V. I. Muronetz; Prions and chaperones: Friends or foes?. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2014, 79, 761-775, 10.1134/s0006297914080045.

- Jacques Fantini; Henri Chahinian; Nouara Yahi; Progress toward Alzheimer's disease treatment: Leveraging the Achilles' heel of Aβ oligomers?. Protein Science 2020, 29, 1748-1759, 10.1002/pro.3906.

- A. B. Matiiv; N. P. Trubitsina; A. G. Matveenko; Y. A. Barbitoff; G. A. Zhouravleva; S. A. Bondarev; Amyloid and Amyloid-Like Aggregates: Diversity and the Term Crisis. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2020, 85, 1011-1034, 10.1134/s0006297920090035.

- Mariya Yu. Suvorina; Olga M. Selivanova; Elizaveta I. Grigorashvili; Alexey D. Nikulin; Victor V. Marchenkov; Alexey K. Surin; Oxana V. Galzitskaya; Studies of Polymorphism of Amyloid-β 42 Peptide from Different Suppliers. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease 2015, 47, 583-593, 10.3233/jad-150147.

- Yana A. Zabrodskaya; Dmitry V. Lebedev; Marja A. Egorova; Aram A. Shaldzhyan; Alexey Shvetsov; Alexander Kuklin; Daria S. Vinogradova; Nikolay V. Klopov; Oleg V. Matusevich; Taisiia Cheremnykh; et al.Rajeev DattaniVladimir V. Egorov The amyloidogenicity of the influenza virus PB1-derived peptide sheds light on its antiviral activity. Biophysical Chemistry 2018, 234, 16-23, 10.1016/j.bpc.2018.01.001.

- Rundong Hu; Baiping Ren; Mingzhen Zhang; Hong Chen; Yonglan Liu; Lingyun Liu; Xiong Gong; Binbo Jiang; Jie Ma; Jie Zheng; et al. Seed-Induced Heterogeneous Cross-Seeding Self-Assembly of Human and Rat Islet Polypeptides. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 784-792, 10.1021/acsomega.6b00559.

- Ibrahim Javed; Zhenzhen Zhang; Jozef Adamcik; Nicholas Andrikopoulos; Yuhuan Li; Daniel E. Otzen; Sijie Lin; Raffaele Mezzenga; Thomas P. Davis; Feng Ding; et al.Pu Chun Ke Accelerated Amyloid Beta Pathogenesis by Bacterial Amyloid FapC. Advanced Science 2020, 7, 202001299, 10.1002/advs.202001299.

- Pu Chun Ke; Ruhong Zhou; Louise C. Serpell; Roland Riek; Tuomas P. J. Knowles; Hilal A. Lashuel; Ehud Gazit; Ian W. Hamley; Thomas P. Davis; Marcus Fändrich; et al.Daniel Erik OtzenMatthew R. ChapmanChristopher M. DobsonDavid S. EisenbergRaffaele Mezzenga Half a century of amyloids: past, present and future. Chemical Society Reviews 2020, 49, 5473-5509, 10.1039/c9cs00199a.

- Annalisa Pastore; Francesco Raimondi; Lawrence Rajendran; Piero Andrea Temussi; Why does the Aβ peptide of Alzheimer share structural similarity with antimicrobial peptides?. Communications Biology 2020, 3, 1-7, 10.1038/s42003-020-0865-9.

- Nir Salinas; Einav Tayeb-Fligelman; Massimo D. Sammito; Daniel Bloch; Raz Jelinek; Dror Noy; Isabel Usón; Meytal Landau; The amphibian antimicrobial peptide uperin 3.5 is a cross-α/cross-β chameleon functional amyloid. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118, e2014442118, 10.1073/pnas.2014442118.

- Giovanna Batoni; Giuseppantonio Maisetta; Semih Esin; Therapeutic Potential of Antimicrobial Peptides in Polymicrobial Biofilm-Associated Infections. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 482, 10.3390/ijms22020482.

- Mithoor Divyashree; Madhu K. Mani; Dhanasekhar Reddy; Ranjith Kumavath; Preetam Ghosh; Vasco Azevedo; Debmalya Barh; Clinical Applications of Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs): Where do we Stand Now?. Protein & Peptide Letters 2020, 27, 120-134, 10.2174/0929866526666190925152957.

- Stanislav R. Kurpe; Sergei Yu. Grishin; Alexey K. Surin; Alexander V. Panfilov; Mikhail V. Slizen; Saikat D. Chowdhury; Oxana V. Galzitskaya; Antimicrobial and Amyloidogenic Activity of Peptides. Can Antimicrobial Peptides Be Used Against SARS-CoV-2?. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 9552, 10.3390/ijms21249552.

- Nusrat Shahin Qureshi; Jasleen Kaur Bains; Sridhar Sreeramulu; Harald Schwalbe; Boris Fürtig; Conformational switch in the ribosomal protein S1 guides unfolding of structured RNAs for translation initiation. Nucleic Acids Research 2018, 46, 10917-10929, 10.1093/nar/gky746.

- Paul E Lund; Surajit Chatterjee; May Daher; Nils G Walter; Protein unties the pseudoknot: S1-mediated unfolding of RNA higher order structure. Nucleic Acids Research 2019, 48, 2107-2125, 10.1093/nar/gkz1166.

- Muhammad S. Azam; Carin K. Vanderpool; Translation inhibition from a distance: The small RNA SgrS silences a ribosomal protein S1‐dependent enhancer. Molecular Microbiology 2020, 114, 391-408, 10.1111/mmi.14514.

- Z. S. Kutlubaeva; H. V. Chetverina; A. B. Chetverin; The Contribution of Ribosomal Protein S1 to the Structure and Function of Qβ Replicase. Acta Naturae 1970, 9, 24-30.

- Madoka Kitakawa; Katsumi Isono; An amber mutation in the gene rpsA for ribosomal protein S1 in Escherichia coli. Molecular Genetics and Genomics 1982, 185, 445-447, 10.1007/bf00334137.

- Michael A. Sorensen; Jens Fricke; Steen Pedersen; Ribosomal protein S1 is required for translation of most, if not all, natural mRNAs in Escherichia coli in vivo. Journal of Molecular Biology 1998, 280, 561-569, 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1909.

- Evgenia I. Deryusheva; Andrey V. Machulin; Maxim A. Matyunin; Oxana V. Galzitskaya; Investigation of the Relationship between the S1 Domain and Its Molecular Functions Derived from Studies of the Tertiary Structure.. Molecules 2019, 24, 3681, 10.3390/molecules24203681.

- Andrey Machulin; Evgenia Deryusheva; Mikhail Lobanov; Oxana Galzitskaya; Repeats in S1 Proteins: Flexibility and Tendency for Intrinsic Disorder. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20, 2377, 10.3390/ijms20102377.

- Mohd. Amir; Vijay Kumar; Ravins Dohare; Asimul Islam; Faizan Ahmad; Imtaiyaz Hassan; Sequence, structure and evolutionary analysis of cold shock domain proteins, a member of OB fold family. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 2018, 31, 1903-1917, 10.1111/jeb.13382.

- Evgenia Deryusheva; Andrey Machulin; Olga M. Selivanova; Oxana V. Galzitskaya; Taxonomic distribution, repeats, and functions of the S1 domain-containing proteins as members of the OB-fold family. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics 2017, 85, 602-613, 10.1002/prot.25237.

- Sergey G. Guryanov; Olga M. Selivanova; Alexey D. Nikulin; Gennady A. Enin; Bogdan Melnik; Dmitry Kretov; Igor N. Serdyuk; Lev P. Ovchinnikov; Formation of Amyloid-Like Fibrils by Y-Box Binding Protein 1 (YB-1) Is Mediated by Its Cold Shock Domain and Modulated by Disordered Terminal Domains. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e36969, 10.1371/journal.pone.0036969.

- Stanislav R. Kurpe; Sergei Yu. Grishin; Alexey K. Surin; Olga M. Selivanova; Roman S. Fadeev; Ylyana F. Dzhus; Elena Yu. Gorbunova; Leila G. Mustaeva; Vyacheslav N. Azev; Oxana V. Galzitskaya; et al. Antimicrobial and Amyloidogenic Activity of Peptides Synthesized on the Basis of the Ribosomal S1 Protein from Thermus Thermophilus. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 6382, 10.3390/ijms21176382.

- Carlos Juan; Carmen Peña; Antonio Oliver; Host and Pathogen Biomarkers for Severe Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infections. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2017, 215, S44-S51, 10.1093/infdis/jiw299.

- Yu‐Xuan Ma; Chen‐Yu Wang; Yuan‐Yuan Li; Jing Li; Qian‐Qian Wan; Ji‐Hua Chen; Franklin R. Tay; Li‐Na Niu; Considerations and Caveats in Combating ESKAPE Pathogens against Nosocomial Infections. Advanced Science 2019, 7, 1901872, 10.1002/advs.201901872.

- Wontae Hwang; Sang Sun Yoon; Virulence Characteristics and an Action Mode of Antibiotic Resistance in Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 1-15, 10.1038/s41598-018-37422-9.

- Mohd W. Azam; Asad U. Khan; Updates on the pathogenicity status of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Drug Discovery Today 2019, 24, 350-359, 10.1016/j.drudis.2018.07.003.

- Hyun Kim; Ju Hye Jang; Sun Chang Kim; Ju Hyun Cho; Development of a novel hybrid antimicrobial peptide for targeted killing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2020, 185, 111814, 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111814.

- Muhammad Yasir; Debarun Dutta; Mark D. P. Willcox; Comparative mode of action of the antimicrobial peptide melimine and its derivative Mel4 against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 1-12, 10.1038/s41598-019-42440-2.

- Songhita Mukhopadhyay; A. S. Bharath Prasad; Chetan H. Mehta; Usha Y. Nayak; Antimicrobial peptide polymers: no escape to ESKAPE pathogens—a review. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2020, 36, 1-14, 10.1007/s11274-020-02907-1.

- Robert Dec; Wojciech Dzwolak; Extremely Amyloidogenic Single-Chain Analogues of Insulin’s H-Fragment: Structural Adaptability of an Amyloid Stretch. Langmuir 2020, 36, 12150-12159, 10.1021/acs.langmuir.0c01747.

- Hafida Bouziane; Abdallah Chouarfia; Sequence- and structure-based prediction of amyloidogenic regions in proteins. Soft Computing 2019, 24, 3285-3308, 10.1007/s00500-019-04087-z.

- Vitaly V. Kushnirov; Alexander A. Dergalev; Alexander I. Alexandrov; Proteinase K resistant cores of prions and amyloids. Prion 2019, 14, 11-19, 10.1080/19336896.2019.1704612.

- Alexey K. Surin; Sergei Yu. Grishin; Oxana V. Galzitskaya; Determination of amyloid core regions of insulin analogues fibrils. Prion 2020, 14, 149-162, 10.1080/19336896.2020.1776062.

- Sergiy Garbuzynskiy; Michail Yu. Lobanov; Oxana V. Galzitskaya; FoldAmyloid: a method of prediction of amyloidogenic regions from protein sequence. Bioinformatics 2009, 26, 326-332, 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp691.

- Mikael Oliveberg; Waltz, an exciting new move in amyloid prediction. Nature Methods 2010, 7, 187-188, 10.1038/nmeth0310-187.

- Ian Walsh; Flavio Seno; Silvio C.E. Tosatto; Antonio Trovato; PASTA 2.0: an improved server for protein aggregation prediction. Nucleic Acids Research 2014, 42, W301-W307, 10.1093/nar/gku399.

- Oscar Conchillo-Solé; Natalia S. De Groot; Francesc X. Avilés; Josep Vendrell; Xavier Daura; Salvador Ventura; AGGRESCAN: a server for the prediction and evaluation of "hot spots" of aggregation in polypeptides. BMC Bioinformatics 2007, 8, 65-17, 10.1186/1471-2105-8-65.

- Olga M. Selivanova; Elizaveta I. Grigorashvili; Mariya Yu. Suvorina; Ulyana F. Dzhus; Alexey D. Nikulin; Victor V. Marchenkov; Alexey K. Surin; Oxana V. Galzitskaya; X-ray diffraction and electron microscopy data for amyloid formation of Aβ40 and Aβ42. Data in Brief 2016, 8, 108-113, 10.1016/j.dib.2016.05.020.

- Mantas Ziaunys; Vytautas Smirnovas; Additional Thioflavin-T Binding Mode in Insulin Fibril Inner Core Region. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2019, 123, 8727-8732, 10.1021/acs.jpcb.9b08652.

- Xue-Jiao Ma; Yin-Juan Zhang; Cheng-Ming Zeng; Inhibition of amyloid aggregation of bovine serum albumin by sodium dodecyl sulfate at submicellar concentrations. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2018, 83, 60-68, 10.1134/s000629791801008x.

- Jan Johansson; Charlotte Nerelius; Hanna Willander; Jenny Presto; Conformational preferences of non-polar amino acid residues: An additional factor in amyloid formation. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2010, 402, 515-518, 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.10.062.

- Jing Zhang; Lei Xin; Baozhen Shan; Weiwu Chen; Mingjie Xie; Denis Yuen; Weiming Zhang; Zefeng Zhang; Gilles A. Lajoie; Bin Ma; et al. PEAKS DB: De Novo Sequencing Assisted Database Search for Sensitive and Accurate Peptide Identification. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 2012, 11, M111.010587, 10.1074/mcp.m111.010587.

- Sergei Grishin; U. F. Dzhus; O. M. Selivanova; V. A. Balobanov; A. K. Surin; O. V. Galzitskaya; Comparative Analysis of Aggregation of Thermus thermophilus Ribosomal Protein bS1 and Its Stable Fragment. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2020, 85, 344-354, 10.1134/s0006297920030104.

- Matthew Biancalana; Shohei Koide; Molecular mechanism of Thioflavin-T binding to amyloid fibrils. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics 2010, 1804, 1405-1412, 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.04.001.

More

Information

Subjects:

Biochemistry & Molecular Biology; Microbiology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.2K

Entry Collection:

Peptides for Health Benefits

Revision:

1 time

(View History)

Update Date:

20 Jul 2021

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No