| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pelin TELKOPARAN AKILLILAR | + 3546 word(s) | 3546 | 2021-05-14 11:30:27 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | Meta information modification | 3546 | 2021-05-26 08:49:33 | | |

Video Upload Options

Nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) and its major negative modulator Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1) are main players of the cellular defense mechanisms against internal and external cell stressors.

1. Introduction

Cancer is a non-communicable disease with an increasing incidence and mortality in many countries worldwide, which is expected to become the leading cause of death in every continent by the end of this century. According to the global statistical data published by (World Health Organization (WHO), Geneva, Switzerland) the main reason behind the growth of cancer-related deaths is the expansion of the world’s aging population [1]. Another critical phenomenon is that common cancer profiles have been changing in a way that infection and or poverty-related cancers tend to decrease while cancers that are associated with Westernized lifestyle tend to augment [2]. In this context, it is of great importance that researchers define the roles of critical molecular players related to tumor formation, progression, and metastasis. At the molecular level, cell division and death of damaged/mutated cells are tightly controlled by several pathways in order to prevent survival of damaged cells bearing mutations and pass those mutations to the next generations. Sometimes a critically damaged cell can take a life-changing decision and takes steps to secure its own survival despite the cost of transforming into a tumor cell. The steps to be taken in the way of transformation by a precancerous cell are described in the highly cited Weinberg review in detail [3]. Genes and signal transduction pathways common to more than one hallmark of cancer recently gained extra attention as promising therapeutic targets. Among the others, redox signaling emerged as a signal transduction pathway involved in every step of carcinogenesis [4]. Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2), also known as NFE2L2, is considered as the leading transcription factor controlling cellular redox homeostasis and antioxidant pathways [5]. Being the major stress regulator of the cell, NRF2 is involved in tumor formation, progression, and metastasis [6]. For this reason, a large number of studies is currently ongoing to better characterize NRF2 pathway and its roles in cancer. NRF2 displays a complex behavior in carcinogenesis [7]. To fully address the importance of NRF2 pathway in cancer, it is necessary to provide a description of its negative regulator KEAP1, that interacts with NRF2 to downmodulate its expression in cells and strictly control cellular homeostasis [8]. Under normal or low/moderate stress conditions, there is a tight balance between KEAP1 activity and NRF2 protein levels, which provides regulated antioxidant response, detoxification, and prevention of cancer. However, excessive stress, continuous overexpression of NRF2 or downregulation of KEAP1 cause a shift in this balance, which, in turn, acts in favor of carcinogenesis. Unraveling these roles would provide researchers to target NRF2 pathway in a more selective way to fully eradicate cancer without promoting its pro-oncogenic functions also known as the “dark side” of NRF2 [9]. In this respect, experimental studies wherein NRF2 function was abrogated with genetic or chemical approaches, support the notion that this transcription factor plays a cytoprotective role, acting as a tumor suppressor in specific contexts [10][11]. It has also been reported that NRF2 loss is strongly associated with tumor malignancy and metastatic behavior of cancer cells [12]. Moreover, partial or complete depletion of KEAP1 has been shown to promote cancer initiation and growth suggesting that KEAP1 can be also regarded as a tumor suppressor, similarly to NRF2 [13][14]. Based on collective data on NRF2 and KEAP1, there is a growing interest in better defining the therapeutic use of natural obtained or chemically synthesized activators of NRF2 with tumor-suppressing properties [15]. Yet, none of these compounds, either from natural or chemical sources, showed a consistent, stable, and dose-dependent effect to become a solid anticancer drug candidate, due to the context-dependent effects of NRF2 pathway in tumors [16]. Moreover, many studies reported that the abnormal activation of NRF2 is a common event in tumor cells, caused by several factors like somatic mutations, oncogenic signaling, epigenetic changes, metabolic reprograming and altered redox balance in cancer cells [17]. Indeed, abnormal NRF2 expression has been detected in various tumors such as lung, esophageal, laryngeal, skin, pancreas and liver cancers [18]. Despite these observations might argue against the assumption of NRF2 being a tumor suppressor, they actually indicate that NRF2, is a context-dependent transcription factor that can act as an oncogene under certain circumstances. In addition, abnormal KEAP1 expression has been observed in several cancers including lung, liver, pancreas, and ovarian cancers [19]. Thus, based on these data, it appears that there is a fine-tuning between KEAP1 and NRF2 levels and this determines which effect of this pathway will be more prominent under specific circumstances of a certain type of tumor. On the other hand, extensive research is focusing on NRF2 inhibitors in consideration of its cancer promoting roles, especially in the later stages of tumorigenesis [16]. However, these inhibitors may lack specificity and therefore interact with other downstream pathways causing undesired effects. Thus, it is of great importance that these drug candidates will be meticulously tested in large clinical studies in order to identify the specific cohorts of patients and the clinical context most likely having beneficial effects and minimal side toxicity.

2. NRF2 and KEAP1 Signaling Pathway

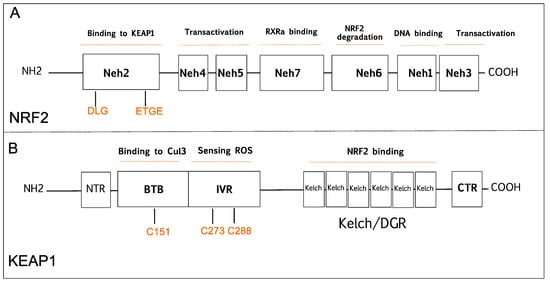

NRF2 was discovered in 1994 and belongs to the Cap and Collar (CNC) basic-region leucine zipper transcription factor family [20]. NRF2 has seven conserved NRF2-ECH homology domains comprising Neh1 to Neh7 (Figure 1A). Neh1, Neh3, Neh4, and Neh5 domains are involved in the transcriptional activation of NRF2 by binding its co-activators. Neh2, Neh6, and Neh7 control the stability of NRF2 through responding as a negative regulatory domain [16]. Neh1 domain is known as a CNC-bZIP domain that allows NRF2 to bind antioxidant response element (ARE), also known as the electrophile response element (EpRE) through interaction with other factors like small musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma (sMAF) [21]. Neh2 domain functions as a major regulatory domain of NRF2 containing ETGE and DLG regions that are required for the interaction with KEAP1. In addition, Neh2 domain has lysine rich residues responsible for the ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation of NRF2 [22]. Neh3 is the transactivation domain recruiting co-activators that are necessary for the transactivation of NRF2 [23]. NRF2 also possesses Neh4 and Neh5 domains containing acid-rich residues that interact with CREB-binding protein with histone acetyltransferase activity (CBP) [24]. The Neh6 domain contains serine-rich residues that can be phosphorylated by Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3b (GSK-3β) and leads to proteasomal degradation of NRF2 through cullin 1 (Cul1)-dependent ubiquitination [25]. The Neh7 domain mediates the binding of RXRα (retinoid X receptor α) that inhibits the NRF2 transcriptional activity [26].

Figure 1. Schematic diagram is showing domain structures of nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (NRF2), and Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1). (A) NRF2 has seven domains (Neh1-7). The Neh1 domain is responsible for DNA binding. The Neh2 domain contains DLG and ETGE motifs that are critical for KEAP1 binding. The Neh3, Neh4, and Neh5 are known transactivation domains. The Neh6 is important for proteasomal degradation of NRF2. The Neh7 domain is responsible for RXRα binding. (B) KEAP1 has five domains; NTR, CTR, BTB, Bric-a-Brac domain binds to Cul3 that is critical for KEAP1 dimerization; IVR, intervening region contains cysteine residues 273 (C273) and 288 (C288) that are important for sensing reactive oxygen species (ROS); the Kelch/DGR domain is important for NRF2 binding. BTB, Broad complex/Tramtrack/Bric-a-Brac; CTR, carboxy-terminal domain; Cul3, Cullin E3 ubiquitin ligase; IVR, Intervening region; Neh, NRF2-ECH homology; NTR, N-terminal region; RXRα, retinoid X receptor-alpha.

KEAP1 was identified as a negative regulator of NRF2 that consists of five functional domains, namely, the N-terminal domain, Broad complex/Tramtrack, Bric-a-Brac domain (BTB), a cysteine-rich intervening region (IVR), Kelch domain, or double glycine repeat (DGR), and carboxyterminal domain (Figure 1B) [27]. The BTB domain is required for homo dimerization of KEAP1 and plays a critical role in ubiquitination of NRF2 through the interaction with the CUL3-based E3 ubiquitin ligase complex [28]. The IVR domain has highly reactive cysteine residues that are responsible for sensing reactive oxygen species (ROS), reactive nitrogen species (RNS), and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) [29][30][31]. The Kelch/DGR domain functions as an NRF2 repressor, and it contains of six Kelch motif repeats, which are required for interaction with Neh2 domain of NRF2 [32].

NRF2 increases cellular antioxidant capacity by controlling the expression of detoxifying and antioxidant genes. Hence, NRF2 has been previously known as a transcription factor that inhibits cancer development. Under homeostatic conditions, KEAP1 plays a critical role in NRF2 activity by binding to DLG/ETGE motifs in the Neh2 domain, and keeps NRF2 protein at low levels in the cytoplasm by promoting its polyubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation [33]. However, under stress conditions, highly reactive cysteine residues in KEAP1 are oxidized, and this modification disrupts the binding of KEAP1 to NRF2 promoting its nuclear translocation, wherein NRF2 forms NRF2-sMaf heterodimers via its Neh1 domain and induces gene expression by binding to the ARE sequences in the promoter regions of NRF2 target genes [33].

KEAP1-NRF2 pathway is one of the major signaling cascades that promote antioxidant defense in normal cells, which is a crucial mechanism in the prevention of cancer development. Many studies have shown that KEAP1 and NRF2 proteins function as tumor suppressors, as their absence leads to tumorigenesis while other work indicates that NRF2 can also promote tumor progression. In the following sections, we will briefly discuss past and present studies focused on this seemingly paradoxical aspect.

2.1. The Tumor Suppressive Role of NRF2 Pathway

A strong indication supporting a tumor-suppressive role of the NRF2 signaling derives from a number of in vivo studies comparing the sensitivity to chemically induced carcinogenesis in NRF2-knockout mice (Nfe2l2-/-) and wild-type mice. In this respect, it was found that NRF2-null mice are more susceptible to developing bladder, skin, and stomach cancer when exposed to chemical carcinogens compared to wild-type mice [34]. In addition, the basal expression level of ARE-mediated genes such as GCL, GST, HMOX1, NQO1, and UGT was found to be significantly suppressed in NRF2-deficient mice compared to the wild-type counterpart [11][35][36]. The mechanism, by which NRF2 protects cells from chemical-induced carcinogenesis, appears to depend on its role in detoxification of chemical carcinogens and ROS, and the induction of DNA damage repair mechanisms that ultimately prevent mutations. In a study with mice harboring SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphisms) in the promoter region of the NRF2 gene, it was shown that reduced NRF2 expression made mice more susceptible to lung injury due to hypoxia [37]. SNP-bearing individuals have lower NRF2 mRNA levels causing an elevated risk of developing non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [13][14].

2.2. The Tumor Suppressive Role of KEAP1

To investigate the direct role of KEAP1 in tumor development, Wakabayashi et al. generated Keap1-knockout mice (Keap1-/-) [38]. Unfortunately, these animals developed hyperkeratosis of the esophagus and fore stomach and showed postnatal lethality within the first 3 weeks [38]. Moreover, Keap1-deficient mice demonstrated upregulation of detoxifying enzymes, including GST and NQO1, and higher NRF2 signaling before death [38]. KEAP1 was also reported to target NRF2/S100P (S100 calcium-binding protein P) pathway in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells, acting as a tumor suppressor. Thus, it was suggested that KEAP1 can be used as a biomarker to monitor NSCLC progression [39].

2.3. The Carcinogenic Role of NRF2

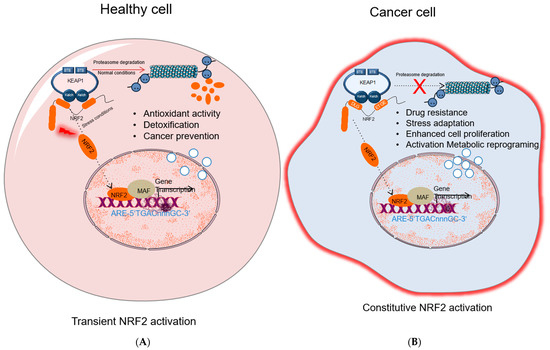

While many studies show that activation of NRF2 protects normal cells against various toxic substances and diseases, it has been shown that the overactivation of NRF2 also supports cancer progression and protects cancer cells from oxidative damage leading to chemoresistance and radioresistance (Figure 2). Elevated levels of NRF2 in cancer induce the upregulation of glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD), transketolase (TKT), 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (PGD), and other metabolic enzymes [40]. The augmented activation of these metabolic enzymes increases the synthesis of purine and amino acids and refills the NADPH pool via the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) leading to metabolic reprogramming for cell proliferation and enhanced antioxidant capacity. Moreover, NRF2 regulates the basal expression of Mdm2, a direct inhibitor of p53 [41]. Therefore, increased Nrf2 expression indirectly downregulates p53 and contributes to tumor survival by suppressing p53-related apoptotic signals.

Figure 2. NRF2 activation in healthy and cancer cells. (A) In healthy cell, under normal conditions NRF2 level is inhibited by KEAP1-mediated proteasomal degradation; under stress conditions, NRF2 dissociates from KEAP1, accumulates in nucleus and activates cytoprotective gene expression. (B) In cancer cells, different molecular mechanisms cause constitutive NRF2 activation that results in drug resistance, stress adaptation, cells proliferation, and activation of metabolic reprogramming and induces expression of genes related to tumor progression. NRF2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; KEAP1, Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1; MAF, small musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma protein; Pol II; RNA polymerase II; ARE: antioxidant response element.

Recent studies have demonstrated that NRF2 plays a critical role in promoting intrinsic and acquired chemoresistance of cancer cells to common chemotherapeutics by activating drug resistance proteins and drug transporters such as UDP-glucuronosyl-transferase 1A1 (UGT1A) and multidrug-resistance-associated protein-1 (MRP1). In a study conducted in human doxorubicin-resistant ovarian cancer cells, NRF2 level was found to be elevated compared to the control cell line, and silencing of NRF2 expression via siRNA restored drug sensitivity [42]. In another study, chemical activation of NRF2 provided a survival advantage to neuroblastoma cells in response to cancer drugs such as cisplatin, doxorubicin, and etoposide [43]. Based on these findings, Cho et al. demonstrated that depletion of NRF2 expression via siRNA knockdown increased the effectiveness of cisplatin in ovarian cancer cells [14].

Moreover, persistent activation of NRF2 was reported to attenuate the toxicity of ionizing radiation and drug treatment in human lung cancer cells, while NRF2 knockdown enhanced cellular response to ionizing radiation and chemotherapeutic drugs. These findings suggest that targeting NRF2 activity alone or in combination with other drugs could be an effective strategy to improve the sensitivity of malignant cells to anticancer therapies [44][45].

Furthermore, recent studies demonstrate the role of NRF2 in tumor metastasis. Constitutively active NRF2 promotes lung cancer via inhibiting degradation of a pro-metastatic transcription factor Bach1 [46]. Overexpression of NRF2 in breast cancer leads to cell proliferation and metastasis by activating the RhoA gene and its downstream signal proteins [47]. The critical role of NRF2 in tumor metastasis and proliferation has been shown in human hepatocellular carcinoma via regulating expression of Bcl-xL and Metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) genes [48]. NRF2 also activates epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) and invasion in pancreatic adenosquamous carcinoma cells by decreasing E-cadherin gene expression [49]. In addition, depletion of NRF2 decreases radiation-induced NSCLC invasion through promoting E-cadherin expression and reducing N-cadherin and MMP2/9 expression [50].

2.4. The Carcinogenic Role of KEAP1

Despite protective effects on cancer progression, studies have also demonstrated the carcinogenic role of KEAP1 mutations in various cancers such as gallbladder, prostate, liver, colorectal, lung, breast, and prostate cancers [51][52][53][54]. Some mutations found in the N-terminal and BTB domains of KEAP1 prevented ubiquitination of NRF2 through the disruption of KEAP1-CUL3 formation, and other mutations in the Kelch domains inhibited interaction of KEAP1-NRF2 and caused stabilization of NRF2 [45][46][55]. Additionally, mutations in KEAP1 were also detected in liver and gallbladder, which caused over expression of antioxidant and phase II detoxification enzymes that have roles in cancer chemo-resistance [53][56].

3. NRF2 Activation Mechanisms in Cancer

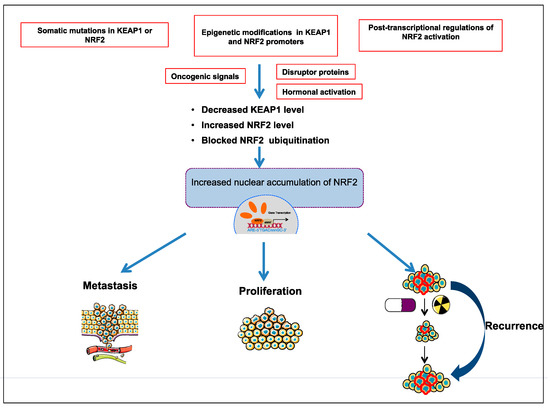

Comprehensive studies validated that NRF2-KEAP1 signaling pathway is activated in several cancers such as skin, lung, bladder, hepatocellular carcinoma, esophagus, ovarian, prostate, pancreatic, and breast cancer [6][52][53][55][57]. The molecular mechanisms responsible for the activation of NRF2 in cancer are schematized in Figure 3 and further details are discussed below:

Figure 3. Different molecular mechanisms are responsible for activation of NRF2-KEAP1 pathway in cancer; somatic mutations in KEAP1 or NRF2; epigenetic modifications in KEAP1 and NRF2 promoter; post-transcriptional activation of NRF2; oncogenic signals; hormonal activation.

3.1. The Somatic Mutations in KEAP1 or NRF2

In cancer, somatic loss of function mutations in KEAP1 or NFE2L2 genes are the most known mechanisms that reduce NRF2-KEAP1 binding and prevent degradation of NRF2 through KEAP1/CUL3/RBX1 E3-ubiquitin ligase complex [45][51]. Increasing evidence has established that the inhibition of NRF2-KEAP1 interaction leads to the overexpression of NRF2 in cancer cells that, in turn, enhances the activation of antioxidant defense system, and proteins involved in chemoresistance and radioresistance system via activating ARE-containing gene expression. Most of the inactivating mutations in the NFE2L2 gene were detected within ETGE and DLG motifs in various cancers such as lung, head, neck, and esophageal carcinoma [53]. It was also reported that the exon2 loss of the NF2EL2 pre-mRNA abolishes the KEAP1–NRF2 protein–protein interaction, thereby inducing NRF2 accumulation and transcriptional activation of its target genes in lung, head, and neck cancers [58].

Inactivating mutations in KEAP1 gene occur frequently in many cancer types and largely affect the NRF2-KEAP1 interaction. Unlike NFE2L2, KEAP1 mutations can be missense or nonsense mutations and observed on the entire gene [45][55]. Some of the mutations in KEAP1 gene lead to deregulation of apoptosis, autophagy, and inflammation by accumulation of BCL2 and p62 proteins [59][60]. The first loss-of-function mutations in Kelch/DGR domain of KEAP1 were reported in human lung adenocarcinoma cell lines [54]. Then, somatic mutations in Kelch/IVR domain of KEAP1 were detected in both human NSCLC cell lines and clinical NSCLC patients’ tumor samples [45][55]. Recently, different research groups also reported that KEAP1 genetic alterations could be novel molecular hallmarks in high neuroendocrine gene expressing lung cancers [61][62].

3.2. Epigenetic Modifications in KEAP1 and NRF2 Promoters

Besides somatic mutations, epigenetic changes at KEAP1 and NFE2L2 promoters may promote to the accumulation of NRF2 and depletion of KEAP1 in cancer cells. Several studies indicate that epigenetic mechanisms play a role in the regulation of KEAP1/NRF2 signaling. In particular, silencing of KEAP1 by different epigenetic mechanisms in many tumors causes NRF2 accumulation. In lung, colon, and prostate cancers, KEAP1 promoter was found to be significantly hypermethylated [43][63][64][65]. Moreover, hypermethylation within the promoter region of KEAP1 was associated with poor clinical prognoses in patients with glioma [66]. On the other hand, it has been shown that NFE2L2 promoter demethylation resulted in NRF2 accumulation and chemoresistance in colon cancer cells [67]. Therefore, from a therapeutic perspective, KEAP1 methylation or NFE2L2 demethylation can be targeted to inhibit abnormal NRF2 expression in different cancers.

3.3. Post-Transcriptional Regulation of NRF2 Activation

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small, 19–25 nucleotides in length, non-coding RNA molecules that play roles in regulating gene expression by sequence-specific binding to mRNA sequences [68]. Several studies concluded that KEAP1 and NRF2 levels can be regulated at the post-transcriptional level in different cancers by abnormal expression of miRNAs targeting these genes. For example, miR-507, miR-634, miR-450a, and miR-129-5p directly target and suppress NRF2 activity. Studies have shown that these miRNAs are downregulated in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and lead to upregulation of NRF2 mRNA [69].

Furthermore, miR-27a, miR-141, miR-144, miR-153, miR-200a, miR-432, and miR-23a modulate KEAP1 mRNA expression and induce NRF2 activation [70]. It was reported that miR-141 is overexpressed in breast and ovarian cancer, and additionally, overexpression of this miRNA increased chemoresistance of HCC cells to 5-fluorouracil through the activation of NRF2-driven antioxidant pathways [71][72].

3.4. Disruptor Proteins

Several disrupting proteins are involved in the activation of NRF2 in cancer. Moreover, p62, also known as sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1), is an autophagy receptor protein that contains the STGE motif, which is similar to the ETGE motif of NRF2. This protein competes with NRF2 for KEAP1 binding and promotes autophagic degradation of KEAP1 [73][74][75][76]. Studies proved that when p62 expression was decreased by siRNA-mediated knockdown, NRF2 and its target genes were downregulated, while the half-life of KEAP1 increased by twofold [73][76]. In addition, elevated p62 contributed to renal cancer progression and hepatocellular carcinoma through the activation of NRF2 [77][78][79]. These studies emphasize the critical role of p62 and NRF2 axis in the regulation of tumor development.

Besides, p21, which is a direct target of p53, associates with ETGE and/or DLG motifs in NRF2 and disrupts NRF2-KEAP1 binding causing NRF2 accumulation [80]. Furthermore, Wilms tumor gene on the X chromosome (WTX) and partner and localizer of BRCA2, also known as PALB2 proteins have been shown to bind KEAP1 and suppress NRF2 ubiquitination [81][82]. Similarly, the protein dipeptidyl peptidase 3 (DPP3) was shown to inhibit NRF2 ubiquitination through binding to KEAP1, thus activating NRF2-dependent gene transcription in breast cancer [83].

3.5. Oncogenic Signals

Oncogenic signals contribute to abnormal NRF2 activation in cancer through transcriptional upregulation of NRF2. DeNicola et al. reported that NRF2 level can be increased by the activation of oncogenic alleles of KRAS, BRAF, and C-MYC (KRASG12D, BRAFV619E, and C-MYCERT12) [84]. In addition, they also demonstrated that K-RAS and B-RAF activated Jun and Myc transcription factors, which, in turn, promoted cancer cell survival and chemoresistance [84]. Similarly, disruption of tumor suppressor phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN) protein-activated NRF2 in human cancers [85]. Moreover, KRAS-ERK signaling pathway plays a critical role in elevation of NRF2 transcription via 12-O Tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) response element that localizes in a regulator site in NRF2 exon1 [86]. Furthermore, the phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-Kinase (PI3K) serine/threonine kinase (AKT) signaling pathway also upregulated NRF2 transcription through the inhibition of GSK3-β-TrCP-induced proteasomal degradation of NRF2 [87].

3.6. Hormonal Activation

Several studies validated the effects of hormonal activation of NRF2 on cancer progression. Gonadotropins and sex steroid hormones, including follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), estrogen (E2), and luteinizing hormone (LH), have been reported to be critical in activation of NRF2 through the induction of ROS that inhibit KEAP1 by oxidation of its cysteine residues [88]. In addition, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) is known to induce expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and hypoxia inducible factor 1α (HIF1α). Thus, FSH contributes to tumor angiogenesis through ROS-mediated NRF2 signaling [89].

References

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424.

- Ferlay, J.; Colombet, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Mathers, C.; Parkin, D.M.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Bray, F. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 144, 1941–1953.

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674.

- Hornsveld, M.; Dansen, T.B. The Hallmarks of Cancer from a Redox Perspective. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2016, 25, 300–325.

- Marengo, B.; Nitti, M.; Furfaro, A.L.; Colla, R.; De Ciucis, C.; Marinari, U.M.; Pronzato, M.A.; Traverso, N.; Domenicotti, C. Redox homeostasis and cellular antioxidant systems: Crucial players in cancer growth and therapy. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 6235641.

- Rojo de la Vega, M.; Chapman, E.; Zhang, D.D. NRF2 and the Hallmarks of Cancer. Cancer Cell 2018, 34, 21–43.

- Wu, S.; Lu, H.; Bai, Y. Nrf2 in cancers: A double-edged sword. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 2252–2267.

- Motohashi, H.; Yamamoto, M. Nrf2–Keap1 defines a physiologically important stress response mechanism. Trends Mol. Med. 2004, 10, 549–557.

- Menegon, S.; Columbano, A.; Giordano, S. The Dual Roles of NRF2 in Cancer. Trends Mol. Med. 2016, 22, 578–593.

- Osburn, W.O.; Karim, B.; Dolan, P.M.; Liu, G.; Yamamoto, M.; Huso, D.L.; Kensler, T.W. Increased colonic inflammatory injury and formation of aberrant crypt foci in Nrf2-deficient mice upon dextran sulfate treatment. Int. J. Cancer 2007, 121, 1883–1891.

- Wakabayashi, N.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Holtzclaw, W.D.; Kang, M.I.; Kobayashi, A.; Yamamoto, M.; Kensler, T.W.; Talalay, P. Protection against electrophile and oxidant stress by induction of the phase 2 response: Fate of cysteines of the Keap1 sensor modified by inducers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 2040–2045.

- Rachakonda, G.; Sekhar, K.R.; Jowhar, D.; Samson, P.C.; Wikswo, J.P.; Beauchamp, R.D.; Datta, P.K.; Freeman, M.L. Increased cell migration and plasticity in Nrf2-deficient cancer cell lines. Oncogene 2010, 29, 3703–3714.

- Yamamoto, T.; Yoh, K.; Kobayashi, A.; Ishii, Y.; Kure, S.; Koyama, A.; Sakamoto, T.; Sekizawa, K.; Motohashi, H.; Yamamoto, M. Identification of polymorphisms in the promoter region of the human NRF2 gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 321, 72–79.

- Suzuki, T.; Shibata, T.; Takaya, K.; Shiraishi, K.; Kohno, T.; Kunitoh, H.; Tsuta, K.; Furuta, K.; Goto, K.; Hosoda, F.; et al. Regulatory Nexus of Synthesis and Degradation Deciphers Cellular Nrf2 Expression Levels. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2013, 33, 2402–2412.

- Panieri, E.; Saso, L. Potential applications of NRF2 inhibitors in cancer therapy. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019.

- Panieri, E.; Telkoparan-Akillilar, P.; Suzen, S.; Saso, L. The nrf2/keap1 axis in the regulation of tumor metabolism: Mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 791.

- Liu, Y.; Lang, F.; Yang, C. NRF2 in human neoplasm: Cancer biology and potential therapeutic target. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 107664.

- Jung, B.J.; Yoo, H.S.; Shin, S.; Park, Y.J.; Jeon, S.M. Dysregulation of NRF2 in cancer: From molecular mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Biomol. Ther. 2018, 26, 57–68.

- Leinonen, H.M.; Kansanen, E.; Pölönen, P.; Heinäniemi, M.; Levonen, A.L. Role of the keap1-Nrf2 Pathway in Cancer. Adv. Cancer Res. 2014, 122, 281–320.

- Moi, P.; Chan, K.; Asunis, I.; Cao, A.; Kan, Y.W. Isolation of NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), a NF-E2-like basic leucine zipper transcriptional activator that binds to the tandem NF-E2/AP1 repeat of the β-globin locus control region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 9926–9930.

- Motohashi, H.; Katsuoka, F.; Engel, J.D.; Yamamoto, M. Small Maf proteins serve as transcriptional cofactors for keratinocyte differentiation in the Keap1-Nrf2 regulatory pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 6379–6384.

- Zhang, D.D.; Lo, S.; Cross, J.V.; Templeton, D.J.; Hannink, M. Keap1 is aredox-regulated substrate adaptor protein for a Cul3-dependent ubiquitinligase complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 10941–10953.

- Nioi, P.; Nguyen, T.; Sherratt, P.J.; Pickett, C.B. The Carboxy-Terminal Neh3 Domain of Nrf2 Is Required for Transcriptional Activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 10895–10906.

- Katoh, Y.; Itoh, K.; Yoshida, E.; Miyagishi, M.; Fukamizu, A.; Yamamoto, M. Two domains of Nrf2 cooperatively bind CBP, a CREB binding protein, and synergistically activate transcription. Genes Cells 2001, 6, 857–868.

- Rada, P.; Rojo, A.I.; Chowdhry, S.; McMahon, M.; Hayes, J.D.; Cuadrado, A. SCF/ -TrCP Promotes Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3-Dependent Degradation of the Nrf2 Transcription Factor in a Keap1-Independent Manner. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2011, 31, 1121–1133.

- Wang, H.; Liu, K.; Geng, M.; Gao, P.; Wu, X.; Hai, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Luo, L.; Hayes, J.D.; et al. RXRα inhibits the NRF2-ARE signaling pathway through a direct interaction with the Neh7 domain of NRF2. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 3097–3108.

- Magesh, S.; Chen, Y.; Hu, L. Small Molecule Modulators of Keap1-Nrf2-ARE Pathway as Potential Preventive and Therapeutic Agents. Med. Res. Rev. 2012, 32, 687–726.

- Zipper, L.M.; Timothy Mulcahy, R. The Keap1 BTB/POZ dimerization function is required to sequester Nrf2 in cytoplasm. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 36544–36552.

- Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Holtzclaw, W.D.; Cole, R.N.; Itoh, K.; Wakabayashi, N.; Katoh, Y.; Yamamoto, M.; Talalay, P. Direct evidence that sulfhydryl groups of Keap1 are the sensors regulating induction of phase 2 enzymes that protect against carcinogens and oxidants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 11908–11913.

- Um, H.C.; Jang, J.H.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, C.; Surh, Y.J. Nitric oxide activates Nrf2 through S-nitrosylation of Keap1 in PC12 cells. Nitric Oxide 2011.

- Xie, L.; Gu, Y.; Wen, M.; Zhao, S.; Wang, W.; Ma, Y.; Meng, G.; Han, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, G.; et al. Hydrogen sulfide induces Keap1 S-sulfhydration and suppresses diabetes-accelerated atherosclerosis via Nrf2 activation. Diabetes 2016.

- Itoh, K.; Wakabayashi, N.; Katoh, Y.; Ishii, T.; Igarashi, K.; Engel, J.D.; Yamamoto, M. Keap1 represses nuclear activation of antioxidant responsive elements by Nrf2 through binding to the amino-terminal Neh2 domain. Genes Dev. 1999, 13, 76–86.

- Itoh, K.; Mimura, J.; Yamamoto, M. Discovery of the negative regulator of Nrf2, keap1: A historical overview. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2010, 13, 1665–1678.

- Ramos-Gomez, M.; Dolan, P.M.; Itoh, K.; Yamamoto, M.; Kensler, T.W. Interactive effects of nrf2 genotype and oltipraz on benzo[a]pyrene-DNA adducts and tumor yield in mice. Carcinogenesis 2003, 24, 461–467.

- Itoh, K.; Chiba, T.; Takahashi, S.; Ishii, T.; Igarashi, K.; Katoh, Y.; Oyake, T.; Hayashi, N.; Satoh, K.; Hatayama, I.; et al. An Nrf2/small Maf heterodimer mediates the induction of phase II detoxifying enzyme genes through antioxidant response elements. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997, 236, 313–322.

- Kwak, M.K.; Egner, P.A.; Dolan, P.M.; Ramos-Gomez, M.; Groopman, J.D.; Itoh, K.; Yamamoto, M.; Kensler, T.W. Role of phase 2 enzyme induction in chemoprotection by dithiolethiones. Mutat. Res. Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2001, 480–481, 305–315.

- Hye-Youn Cho, A.E.J. Role of NRF2 in Protection against Hyperoxic Lung Injury in Mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002, 26, 75–182.

- Wakabayashi, N.; Itoh, K.; Wakabayashi, J.; Motohashi, H.; Noda, S.; Takahashi, S.; Imakado, S.; Kotsuji, T.; Otsuka, F.; Roop, D.R.; et al. Keap1-null mutation leads to postnatal lethality due to constitutive Nrf2 activation. Nat. Genet. 2003, 35, 238–245.

- Chien, M.H.; Lee, W.J.; Hsieh, F.K.; Li, C.F.; Cheng, T.Y.; Wang, M.Y.; Chen, J.S.; Chow, J.M.; Jan, Y.H.; Hsiao, M.; et al. Keap1-Nrf2 interaction suppresses cell motility in lung adenocarcinomas by targeting the S100P protein. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 4719–4732.

- Mitsuishi, Y.; Taguchi, K.; Kawatani, Y.; Shibata, T.; Nukiwa, T.; Aburatani, H.; Yamamoto, M.; Motohashi, H. Nrf2 Redirects Glucose and Glutamine into Anabolic Pathways in Metabolic Reprogramming. Cancer Cell 2012, 22, 66–79.

- You, A.; Nam, C.W.; Wakabayashi, N.; Yamamoto, M.; Kensler, T.W.; Kwak, M.K. Transcription factor Nrf2 maintains the basal expression of Mdm2: An implication of the regulation of p53 signaling by Nrf2. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2011, 507, 356–364.

- Shim, G.S.; Manandhar, S.; Shin, D.H.; Kim, T.H.; Kwak, M.K. Acquisition of doxorubicin resistance in ovarian carcinoma cells accompanies activation of the NRF2 pathway. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009, 47, 1619–1631.

- Wang, X.J.; Sun, Z.; Villeneuve, N.F.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, F.; Li, Y.; Chen, W.; Yi, X.; Zheng, W.; Wondrak, G.T.; et al. Nrf2 enhances resistance of cancer cells to chemotherapeutic drugs, the dark side of Nrf2. Carcinogenesis 2008, 29, 1235–1243.

- Yoshino, H.; Murakami, K.; Nawamaki, M.; Kashiwakura, I. Effects of Nrf2 knockdown on the properties of irradiated cell conditioned medium from A549 human lung cancer cells. Biomed. Reports 2018, 8, 461–465.

- Singh, A.; Misra, V.; Thimmulappa, R.K.; Lee, H.; Ames, S.; Hoque, M.O.; Herman, J.G.; Baylin, S.B.; Sidransky, D.; Gabrielson, E.; et al. Dysfunctional KEAP1-NRF2 interaction in non-small-cell lung cancer. PLoS Med. 2006, 3, 1865–1876.

- Lignitto, L.; LeBoeuf, S.E.; Homer, H.; Jiang, S.; Askenazi, M.; Karakousi, T.R.; Pass, H.I.; Bhutkar, A.J.; Tsirigos, A.; Ueberheide, B.; et al. Nrf2 Activation Promotes Lung Cancer Metastasis by Inhibiting the Degradation of Bach1. Cell 2019.

- Zhang, C.; Wang, H.J.; Bao, Q.C.; Wang, L.; Guo, T.K.; Chen, W.L.; Xu, L.L.; Zhou, H.S.; Bian, J.L.; Yang, Y.R.; et al. NRF2 promotes breast cancer cell proliferation and metastasis by increasing RhoA/ROCK pathway signal transduction. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 73593–73606.

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Q.; Zhou, S.; Wen, Q.; Wang, J. Nrf2 is a potential prognostic marker and promotes proliferation and invasion in human hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2015.

- Arfmann-Knubel, S.; Struck, B.; Genrich, G.; Helm, O.; Sipos, B.; Sebens, S.; Schafer, H. The Crosstalk between Nrf2 and TGF-β1 in the Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition of Pancreatic Duct Epithelial Cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132978.

- Zhao, Q.; Mao, A.; Guo, R.; Zhang, L.; Yan, J.; Sun, C.; Tang, J.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H. Suppression of radiation-induced migration of non-small cell lung cancer through inhibition of Nrf2-Notch Axis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 36603.

- Yoo, N.J.; Kim, H.R.; Kim, Y.R.; An, C.H.; Lee, S.H. Somatic mutations of the KEAP1 gene in common solid cancers. Histopathology 2012, 60, 943–952.

- Konstantinopoulos, P.A.; Spentzos, D.; Fountzilas, E.; Francoeur, N.; Sanisetty, S.; Grammatikos, A.P.; Hecht, J.L.; Cannistra, S.A. Keap1 mutations and Nrf2 pathway activation in epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 5081–5089.

- Shibata, T.; Kokubu, A.; Gotoh, M.; Ojima, H.; Ohta, T.; Yamamoto, M.; Hirohashi, S. Genetic Alteration of Keap1 Confers Constitutive Nrf2 Activation and Resistance to Chemotherapy in Gallbladder Cancer. Gastroenterology 2008, 135, 1358–1368.

- Padmanabhan, B.; Tong, K.I.; Ohta, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Scharlock, M.; Ohtsuji, M.; Kang, M.I.; Kobayashi, A.; Yokoyama, S.; Yamamoto, M. Structural basis for defects of Keap1 activity provoked by its point mutations in lung cancer. Mol. Cell 2006, 21, 689–700.

- Ohta, T.; Iijima, K.; Miyamoto, M.; Nakahara, I.; Tanaka, H.; Ohtsuji, M.; Suzuki, T.; Kobayashi, A.; Yokota, J.; Sakiyama, T.; et al. Loss of Keap1 function activates Nrf2 and provides advantages for lung cancer cell growth. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 1303–1309.

- Gañán-Gómez, I.; Wei, Y.; Yang, H.; Boyano-Adánez, M.C.; García-Manero, G. Oncogenic functions of the transcription factor Nrf2. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 65, 750–764.

- Panieri, E.; Buha, A.; Telkoparan-akillilar, P.; Cevik, D.; Kouretas, D.; Veskoukis, A.; Skaperda, Z.; Tsatsakis, A.; Wallace, D.; Suzen, S.; et al. Potential applications of NRF2 modulators in cancer therapy. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 193.

- Goldstein, L.D.; Lee, J.; Gnad, F.; Klijn, C.; Schaub, A.; Reeder, J.; Daemen, A.; Bakalarski, C.E.; Holcomb, T.; Shames, D.S.; et al. Recurrent Loss of NFE2L2 Exon 2 Is a Mechanism for Nrf2 Pathway Activation in Human Cancers. Cell Rep. 2016, 16, 2605–2617.

- Lebovitz, C.B.; Robertson, A.G.; Goya, R.; Jones, S.J.; Morin, R.D.; Marra, M.A.; Gorski, S.M. Cross-cancer profiling of molecular alterations within the human autophagy interaction network. Autophagy 2015, 11, 1668–1687.

- Tian, H.; Zhang, B.F.; Di, J.H.; Jiang, G.; Chen, F.F.; Li, H.Z.; Li, L.T.; Pei, D.S.; Zheng, J.N. Keap1: One stone kills three birds Nrf2, IKKβ and Bcl-2/Bcl-xL. Cancer Lett. 2012, 325, 26–34.

- Derks, J.L.; Leblay, N.; Lantuejoul, S.; Dingemans, A.M.C.; Speel, E.J.M.; Fernandez-Cuesta, L. New Insights into the Molecular Characteristics of Pulmonary Carcinoids and Large Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinomas, and the Impact on Their Clinical Management. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2018, 13, 752–766.

- Fernandez-Cuesta, L.; Peifer, M.; Lu, X.; Sun, R.; Ozretić, L.; Danila, S.; Zander, T.; Leenders, F.; George, J.; Müller, C.; et al. Frequent mutations in chromatin-remodeling genes in pulmonary carcinoids. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3518.

- Muscarella, L.A.; Parrella, P.; D’Alessandro, V.; la Torre, A.; Barbano, R.; Fontana, A.; Tancredi, A.; Guarnieri, V.; Balsamo, T.; Coco, M.; et al. Frequent epigenetics inactivation of KEAP1 gene in non-small cell lung cancer. Epigenetics 2011, 6, 710–719.

- Hanada, N.; Takahata, T.; Zhou, Q.; Ye, X.; Sun, R.; Itoh, J.; Ishiguro, A.; Kijima, H.; Mimura, J.; Itoh, K.; et al. Methylation of the KEAP1 gene promoter region in human colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer 2012, 12, 1–11.

- Zhang, P.; Singh, A.; Yegnasubramanian, S.; Esopi, D.; Bodas, M.; Wu, H.; Bova, G.S.; Biswal, S. Loss of keap 1 Function in prostate Cancer Cells Causes Chemo- and Radio-resistance and Promotes Tumor Growth. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2011, 9, 1–18.

- Muscarella, L.A.; Barbano, R.; D’Angelo, V.; Copetti, M.; Coco, M.; Balsamo, T.; la Torre, A.; Notarangelo, A.; Troiano, M.; Parisi, S.; et al. Regulation of KEAP1 expression by promoter methylation in malignant gliomas and association with patient’s outcome. Epigenetics 2011, 6, 317–325.

- Zhao, X.Q.; Zhang, Y.F.; Xia, Y.F.; Zhou, Z.M.; Cao, Y.Q. Promoter demethylation of nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 gene in drug-resistant colon cancer cells. Oncol. Lett. 2015, 10, 1287–1292.

- Esquela-Kerscher, A.; Slack, F.J. Oncomirs—MicroRNAs with a role in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 259–269.

- Yamamoto, S.; Inoue, J.; Kawano, T.; Kozaki, K.I.; Omura, K.; Inazawa, J. The impact of miRNA-based molecular diagnostics and treatment of NRF2-stabilized tumors. Mol. Cancer Res. 2014, 12, 58–68.

- Zimta, A.A.; Cenariu, D.; Irimie, A.; Magdo, L.; Nabavi, S.M.; Atanasov, A.G.; Berindan-Neagoe, I. The role of Nrf2 activity in cancer development and progression. Cancers 2019, 11, 1755.

- Shi, L.; Wu, L.; Chen, Z.; Yang, J.; Chen, X.; Yu, F.; Zheng, F.; Lin, X. MiR-141 activates Nrf2-dependent antioxidant pathway via down-regulating the expression of keap1 conferring the resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma cells to 5-fluorouracil. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 35, 2333–2348.

- Wei, J.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Z.; Bi, S.; Song, D.; Dai, Y.; Wang, T.; Qiu, L.; Wen, L.; et al. Aldose reductase regulates miR-200a-3p/141-3p to coordinate Keap1-Nrf2, Tgfβ1/2, and Zeb1/2 signaling in renal mesangial cells and the renal cortex of diabetic mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 67, 91–102.

- Copple, I.M.; Lister, A.; Obeng, A.D.; Kitteringham, N.R.; Jenkins, R.E.; Layfield, R.; Foster, B.J.; Goldring, C.E.; Park, B.K. Physical and functional interaction of sequestosome 1 with Keap1 regulates the Keap1-Nrf2 cell defense pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 16782–16788.

- Jain, A.; Lamark, T.; Sjøttem, E.; Larsen, K.B.; Awuh, J.A.; Øvervatn, A.; McMahon, M.; Hayes, J.D.; Johansen, T. p62/SQSTM1 is a target gene for transcription factor NRF2 and creates a positive feedback loop by inducing antioxidant response element-driven gene transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 22576–22591.

- Komatsu, M.; Kurokawa, H.; Waguri, S.; Taguchi, K.; Kobayashi, A.; Ichimura, Y.; Sou, Y.S.; Ueno, I.; Sakamoto, A.; Tong, K.I.; et al. The selective autophagy substrate p62 activates the stress responsive transcription factor Nrf2 through inactivation of Keap1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010, 12, 213–223.

- Lau, A.; Wang, X.-J.; Zhao, F.; Villeneuve, N.F.; Wu, T.; Jiang, T.; Sun, Z.; White, E.; Zhang, D.D. A Noncanonical Mechanism of Nrf2 Activation by Autophagy Deficiency: Direct Interaction between Keap1 and p62. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010, 30, 3275–3285.

- Genschik, P.; Sumara, I.; Lechner, E. The emerging family of CULLIN3-RING ubiquitin ligases (CRL3s): Cellular functions and disease implications. EMBO J. 2013, 32, 2307–2320.

- Inami, Y.; Waguri, S.; Sakamoto, A.; Kouno, T.; Nakada, K.; Hino, O.; Watanabe, S.; Ando, J.; Iwadate, M.; Yamamoto, M.; et al. Persistent activation of Nrf2 through p62 in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. J. Cell Biol. 2011, 193, 275–284.

- Umemura, A.; He, F.; Taniguchi, K.; Nakagawa, H.; Yamachika, S.; Font-Burgada, J.; Zhong, Z.; Subramaniam, S.; Raghunandan, S.; Duran, A.; et al. p62, Upregulated during Preneoplasia, Induces Hepatocellular Carcinogenesis by Maintaining Survival of Stressed HCC-Initiating Cells. Cancer Cell 2016, 29, 935–948.

- Chen, W.; Sun, Z.; Wang, X.J.; Jiang, T.; Huang, Z.; Fang, D.; Zhang, D.D. Direct Interaction between Nrf2 and p21Cip1/WAF1 Upregulates the Nrf2-Mediated Antioxidant Response. Mol. Cell 2009, 34, 663–673.

- Camp, N.D.; James, R.G.; Dawson, D.W.; Yan, F.; Davison, J.M.; Houck, S.A.; Tang, X.; Zheng, N.; Major, M.B.; Moon, R.T. Wilms Tumor Gene on X Chromosome (WTX) Inhibits Degradation of NRF2 Protein through Competitive Binding to KEAP1 Protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 6539–6550.

- Ma, J.; Cai, H.; Wu, T.; Sobhian, B.; Huo, Y.; Alcivar, A.; Mehta, M.; Cheung, K.L.; Ganesan, S.; Kong, A.-N.T.; et al. PALB2 Interacts with KEAP1 To Promote NRF2 Nuclear Accumulation and Function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2012, 32, 1506–1517.

- Lu, K.; Alcivar, A.L.; Ma, J.; Foo, T.K.; Zywea, S.; Mahdi, A.; Huo, Y.; Kensler, T.W.; Gatza, M.L.; Xia, B. NRF2 induction supporting breast cancer cell survival is enabled by oxidative stress-induced DPP3-KEAP1 interaction. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 2881–2892.

- Denicola, G.M.; Karreth, F.A.; Humpton, T.J.; Gopinathan, A.; Wei, C.; Frese, K.; Mangal, D.; Yu, K.H.; Yeo, C.J.; Calhoun, E.S.; et al. Oncogene-induced Nrf2 transcription promotes ROS detoxification and tumorigenesis. Nature 2011, 475, 106–110.

- Rojo, A.I.; Rada, P.; Mendiola, M.; Ortega-Molina, A.; Wojdyla, K.; Rogowska-Wrzesinska, A.; Hardisson, D.; Serrano, M.; Cuadrado, A. The PTEN/NRF2 axis promotes human carcinogenesis. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 21, 2498–2514.

- Tao, S.; Wang, S.; Moghaddam, S.J.; Ooi, A.; Chapman, E.; Wong, P.K.; Zhang, D.D. Oncogenic KRAS Confers Chemoresistance by Upregulating NRF2. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 7430–7441.

- Chowdhry, S.; Zhang, Y.; Mcmahon, M. Nrf2 is controlled by two distinct β -TrCP recognition motifs in its Neh6 domain, one of which can be modulated by GSK-3 activity. Oncogene 2014, 32, 3765–3781.

- Liao, H.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Yi, X.; Feng, Y. NRF2 is overexpressed in ovarian epithelial carcinoma and is regulated by gonadotrophin and sex-steroid hormones. Oncol. Rep. 2012, 27, 1918–1924.

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Ma, J.; Yi, X.; Zhu, Y.; Xi, X.; Feng, Y.; Jin, Z. AntiReactive oxygen species regulate FSH-induced expression of vascular endothelial growth factor via Nrf2 and HIF1a signaling in human epithelial ovarian cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2013, 29, 1429–1434.