Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ferenc Papp | + 3114 word(s) | 3114 | 2021-12-22 09:05:40 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | Meta information modification | 3114 | 2021-12-23 01:41:56 | | | | |

| 3 | Ferenc Papp | + 33 word(s) | 3147 | 2021-12-29 09:42:49 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Papp, F. Peptide Inhibitors of Kv1.5. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17448 (accessed on 16 January 2026).

Papp F. Peptide Inhibitors of Kv1.5. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17448. Accessed January 16, 2026.

Papp, Ferenc. "Peptide Inhibitors of Kv1.5" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17448 (accessed January 16, 2026).

Papp, F. (2021, December 22). Peptide Inhibitors of Kv1.5. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17448

Papp, Ferenc. "Peptide Inhibitors of Kv1.5." Encyclopedia. Web. 22 December, 2021.

Copy Citation

The human voltage gated potassium channel Kv1.5 that conducts the IKur current is a key determinant of the atrial action potential. This channel is an attractive target for the management of Atrial Fibrillation (AF). A wide range of peptide toxins from venomous animals are targeting ion channels, including mammalian channels. These peptides usually have a much larger interacting surface with the ion channel compared to small molecule inhibitors and thus, generally confer higher selectivity to the peptide blockers. To date, literature has known two peptides that inhibit IKur: Ts6 and Osu1. T

Kv1.5

IKur

peptide inhibitor

atrial fibrillation

1. Diseases Related to Kv1.5

The most well-known channelopathy associated with the Kv1.5 channel is atrial fibrillation (AF). Today, a plethora of mutations have already been identified as causes of AF. Among them there are loss of function (LOF) mutations (E375X, Y155C, D469E and P488S), which make the atrial action potential (AP) prolonged, and gain of function (GOF) mutations (E48G, A305T and D332H), which shorten the AP. In the former case, the prolongation of the AP and the effective refractory period (ERP) increases the probability of early afterdepolarizations (EADs). However, during GOF mutations, the shortening of the ERP will increase the excitability of the atrial tissue as a potential mechanism behind AF [1][2].

Besides atrial fibrillation, mutations of the Kv1.5 channel gene can result in various diseases. Remillard and colleagues identified 17 single-nucleotide polymorphisms of the Kv1.5 gene in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) patients [3], which may contribute to the downregulation of KCNA5, causing the increase of the vascular tone. Fu and colleagues [4] found that in intrauterine growth retardation, while Kv1.5 expression was decreased, the tyrosine-phosphorylation of these channels was significantly increased. This process led to the proliferation of the pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells, which eventually resulted in the thickening of the pulmonary arterial wall, i.e., PAH. MacFarlane and Sontheimer [5] showed in astrocytes that Kv1.5 is associated with Src family protein tyrosine kinases, which are responsible for astrocyte proliferation. This connection between Kv1.5 and astrocyte proliferation stimulated numerous tumor-related studies. Preussat and colleagues [6] found high Kv1.5 expression in human gliomas, which was the most prominent in astrocytomas, moderate in oligodendrogliomas and low in glioblastomas. Bielanska and colleagues pointed out that in stomach, pancreatic and breast cancer, the high expression of Kv1.5 was due to the presence of infiltrating inflammatory cells [7]. However, in bladder, skin, ovary and lymph node cancers, Kv1.5 was highly expressed in the tumorigenic cells. According to Vallejo-Gracia and colleagues [8], Kv1.5 expression shows an inverse correlation with lymphoma aggressiveness; therefore, the level of this protein can be useful in prognosis, treatment and outcome prediction as well.

2. Atrial Fibrillation and Possible Pharmacological Treatments

AF is characterized by an irregular and often rapid heart rate. In people with AF, blood flow is significantly slowed in the atria, which may cause blood to pool, greatly increasing the chances of blood clot formation. When a piece of a clot breaks off, it can travel to the brain and cause a stroke, which is one of the most serious consequences of AF. However, blood clots may circulate to other organs as well, blocking blood flow and causing ischemia. AF is the most common serious abnormal heart rhythm and, as of 2020, affects more than 33 million people worldwide [9]. As of 2014, it affected about 2 to 3% of the population of Europe and North America [10]. Due to AF, some patients need to constantly take blood thinners (platelet aggregation inhibitors and/or anticoagulants) to prevent blood clots, which can be very costly and can have very serious side effects, such as bleeding or hemorrhagic stroke.

The possible pharmacological strategies for AF treatment are the following:

- -

-

Development and improvement of existing antiarrhythmic agents: Amiodarone derivates, Multi-channel blockers, etc.

- -

-

Atrial selective therapeutic agents (ARDA): IKur blocker; IK,Ach blocker; INa, IKr blockers

- -

-

Upstream therapy agents, drugs affecting: structural remodeling, inflammation, hypertrophy, oxidative stress, etc.

- -

-

Gap junction modulators: Antiarrhythmic peptides affecting connexins Cx40 and Cx43

The most promising strategy to treat AF that avoids ventricular proarrhythmic side effects is the development of drugs known as “atrial selective drugs”. This concept would exploit distinct differences in expression patterns of individual ion channels and their different contribution to refractoriness between atrial and ventricular myocytes. Such atrial specific targets would be the following three known atrial specific ionic currents: (a) the ultra-rapid delayed rectified potassium current (IKur); (b) the acetylcholine-sensitive inward rectifier potassium current (IK,ACh); (c) the constitutively active IK,ACh currents (i.e., which are active even in the absence of agonists at muscarinic receptors).

Inhibition of the ion flow through Kv1.5, i.e., blocking IKur, eliminates a component of the repolarizing current during atrial AP, thus prolonging the duration of the AP [11]. Almost all of the known Kv1.5 blockers are exclusively small molecules [12][13][14][15]. Pharmaceutical companies have made great efforts to develop selective IKur blockers as new pharmacological agents against AF. As a result, many new IKur blockers have been developed and tested since the beginning of this century: AVE0118, XEN-D101, DPO-1, vernakalant, etc.

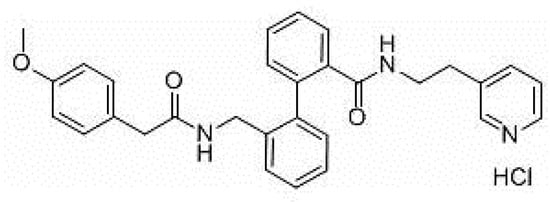

AVE0118 (Figure 1) is a biphenyl derivative developed by Sanofi-Aventis. AVE0118 blocks IKur at micromolar concentrations in both native human atrial cells and Kv1.5 channel systems. In addition to the blocking of IKur, the drug also blocked Ito and IK,ACh currents at a similar concentration range [16][17].

Figure 1. Structure of AVE0118.

AVE0118 shortened APD and ERP in atrial tissue from patients in sinus rhythm (SR), whereas APD/ERP was only slightly prolonged in tissues from patients in AF [17]. This observation is consistent with a previous study with the non-selective IKur blocker 4-aminopyridine [18]. AVE0118 has not been published in clinical trials and it appears that its development as a potential antirrhythmic drug is likely to have been halted. However, the compound was recently proposed as a new pharmacological tool for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea [19].

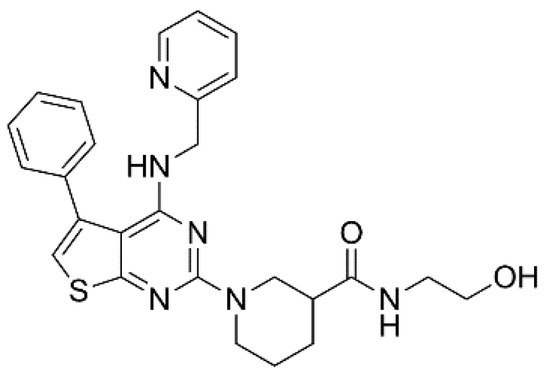

XEN-D0101 (Figure 2) is an experimental compound developed by a small R&D company (Xention Ltd., Cambridge, UK). A first clinical trial with XEN-D0103 did not reduce the burden of AF in patients with paroxysmal AF [20].

Figure 2. Structure of XEN-D0101.

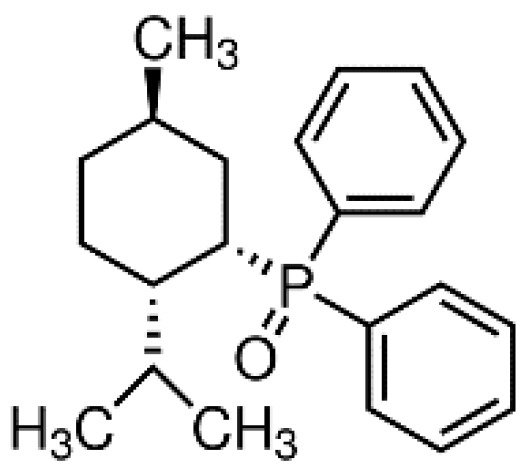

DPO-1 (Diphenylphosphine oxide, Figure 3). DPO-1 blocks IKur rate-dependently at nanomolar concentrations in isolated human atrial myocytes. DPO-1 blocks other currents (such as Ito) at higher micromolar concentrations. Furthermore, DPO-1 induced prolongation of APD in AF plateau, elevation and shortening in SR only in human atrial tissue and not in the ventricle [21].

Figure 3. Structure of DPO-1.

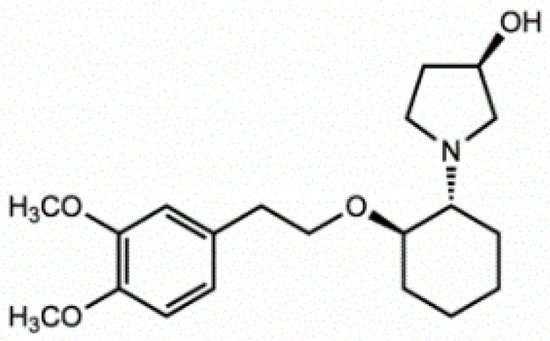

Vernakalant (RSD1235, Cardiome and Astellas, Figure 4) is the molecule in the most advanced phase of study. It was approved by the European authorities, but the FDA did not allow intravenous conversion of AF. Vernakalant inhibited IKur in a positive frequency-dependent manner [22][23]. However, in human atrial cardiomyocytes, its effects on Ito1 are small. In human atrial preparations vernakalant suppresses upstroke velocity, suggesting relevant inhibition of INa [22][23], so it can be considered a multichannel inhibitor rather than a selective IKur blocker. Vernakalant has rapid offset kinetics at sodium channels, so it was not expected to cause proarrhythmia and conduction disturbances at low heart rates [24][25]. However, vernakalant slowed conduction velocity at physiological heart rate both in the atria and in the ventricles of human hearts, calling into question the atrial selectivity of the drug effect [26]. Numerous clinical studies have shown the safety and efficacy of vernakalant in the transformation of AF. The AVRO study (phase III clinical study) demonstrated that vernakalant has superior efficacy compared with amiodarone in the acute conversion of recent cardiac arrhythmias AF [27][28]. In another study, vernakalant was shown to be safe and effective in combination with electrical cardioversion [29] and was approved for clinical practice in the European Union in 2010 (but not in the US [30]).

Figure 4. Stucture of Vernakalant.

3. Peptide Modulators of the Kv Channels

Animal venoms are a complex cocktail of oligopeptides, free amino acids, nucleotides, low molecular weight salts, organic compounds, peptides and proteins [31]. These venoms are employed for prey hunting and protection against predators [32]. In this complex mixture of bioactive molecules, the lethal toxin often represents only a minor proportion, along which many other non-lethal components with interesting bioactivities are present, which can be used for the development of pharmaceutical agents, insecticides and research tools in the characterization of ion channels [33].

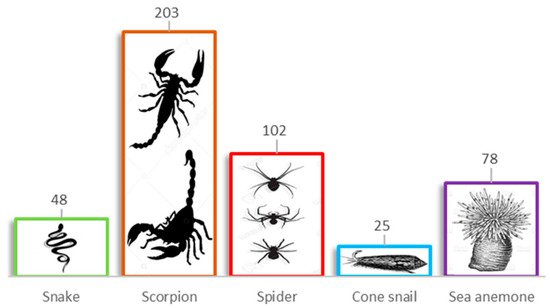

Research on peptide modulators of Kv channels started in the 1980s [15]. To date, ~460 toxins have been reported exclusively for voltage-gated K+ channels (Figure 5), scorpion venoms being the major source of these molecules with 203 entries, followed by the spider venoms with 102 [34][35][36]. These arachnid venom-derived peptides interact with Kv channels in two different modes: either as pore blockers or as gating modifiers, with a very specific interaction with different regions of the ion channels.

Figure 5. Peptide modulators of the voltage-gated potassium (Kv) channels. Numbers above the boxes indicate the number of toxins isolated to target Kv channels.

3.1. Pore Blocker Peptides

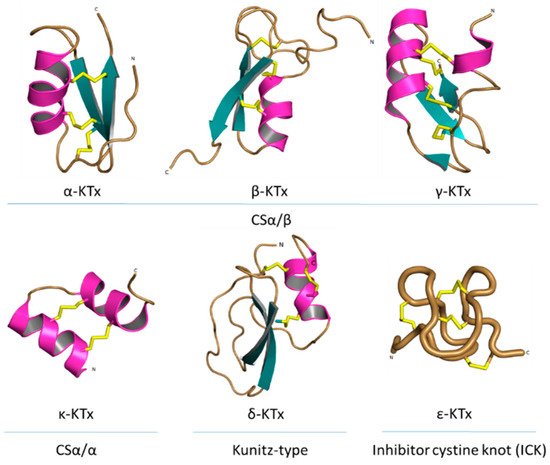

All known scorpion toxins affecting potassium channels (KTx) physically occlude the channel pore, which makes them pore blockers [37]. Based on homology, cysteine pairing pattern and activity, KTxs have been classified into six families: α-KTx, β-KTx, γ-KTx, κ-KTx, δ-KTx [38] and ε-KTx (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Structural folds present in the KTx families. α-KTx: MgTx (1MTX), β-KTx: HgeScplp1 (5IPO), γ-KTx: Ergtoxin (1PX9), κ-KTx: OmTx2 (1WQC), δ-KTx: LmKTT-1a (2M01) and ε-KTx: Ts11 (2MSF). PDB entries are shown in parentheses.

The α-KTx family is the largest family, with 174 members grouped in 31 subfamilies, followed by the β-KTx family with 35 members grouped in 3 subfamilies and the γ-KTx family with 30 members grouped in 5 subfamilies [36][39][40][41]. All these three families share a common structural motif comprising one or two α-helices connected to a triple-stranded antiparallel β-sheet stabilized by three or four disulfide bonds (CSα/β) [40]. The majority of the members of the α-KTx family have been isolated from the venoms of scorpions of the Buthidae family [42]. These peptides range from 23 to 43 residues in size and recognize Shaker-type Kv channels and Ca2+-activated K+ channels [43]. β-KTx peptides are longer than the α-KTx, ranging from 45 to 75 residues in size. The difference between the sizes of these families can be explained by an N-terminus α-helix with cytolytic and/or antimicrobial activity, followed by the C-terminal region with a CSα/β motif that confers the K+ channels blocking activity [44]. Peptides of the γ-KTx family were discovered in the venom of scorpions of the genus Centruroides, Mesobuthus and Buthus [45]. Their length ranges from 36 to 47 residues, and they are described as mainly targeting K+ channels of the ERG (ether-á-go-go gene) family [46].

The κ-KTx family is comprised of 18 members grouped in 5 subfamilies. All these peptides have been isolated from scorpion venoms of the genus Heterometrus and Opisthacanthus. Peptides of this family consist of 22 to 28 amino acid residues and are considered weak inhibitors of K+ channels (all of them showing effect in the µM range). The structure of κ-KTx peptides is characterized by two parallel α-helices linked by two disulfide bridges (CSα/α) [47].

The δ-KTx family is comprised of 7 members grouped in 3 subfamilies, ranging from 59 to 70 residues, which have been isolated from the venom of scorpions of the genus Hadrurus, Mesobuthus and Lychas. The members of the δ-KTx family are characterized by a Kunitz-type fold, which is represented by two antiparallel β-strands and two, or more often, one helical region [48]. Moreover, δ-KTx members possess a dual activity inhibiting proteolytic enzymes (e.g., trypsin) in nanomolar concentration and blocking Kv channels [49].

The ε-KTx family is the smallest one. It is comprised of only two members (29 amino acid residues length), both of them isolated from the venom of the scorpion Tityus serrulatus. The structure of these peptides consists of an inhibitor cystine knot type scaffold (ICK). However, the structure is completely devoid of the classical secondary structure elements (α-helix and/or β-strand) [50].

In previous works, a seventh family of KTx is mentioned [42][51]. This family, known as λ-KTx, also presents an ICK scaffold, but unlike the ε-KTx family, the structure is a CSα/β fold. The best-characterized peptide of this family, the λ-MeuTx-1, showed a blocking effect in the Shaker K+ channel but not in other Kv channels [52]. However, nowadays, this peptide has been reclassified into the scorpion calcin-like family, which is why the λ-KTx family does not appear in the classification of the KTx anymore.

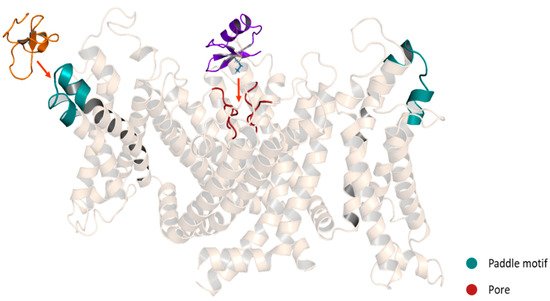

Mechanism of Action of the Pore Blockers

KTxs can interact with Kv channels through different mechanisms. However, three major mechanisms have been described. The first one is the so-called “functional dyad” model, which is the most frequently identified and the best characterized. The dyad is composed of two highly conserved amino acid residues. In the first position, there is a lysine and in the second position, a neighboring aromatic or aliphatic residue [1]. In this model, the β-sheet side of the toxin faces the entrance of the channel pore and the lysine side chain in the selectivity filter (Figure 7). The hydrophobic interaction of the second amino acid is involved mostly in the high-affinity binding [43]. The lysine side chain is attracted to the pore, where a ring of aspartate or glutamate residues surrounds it [53], while the aromatic or aliphatic residue might interact with a tyrosine or tryptophan residue of one of the channel α-subunits [54]. The second mechanism is called the “ring of basic residues”. This mechanism has been demonstrated for the entire α-KTx subfamily 5 and α-KTx4.2 interacting with the KCa2.x channels. In this model, a cluster of basic residues (2-4 Arg and Lys) interacts with residues of the channel situated at the turret and the bottom of the vestibule. However, this cluster is located in the α-helix of the toxin instead of the β-hairpin [54][55]. The last model involved the interaction of the γ-KTxs with the ERG channels. The binding occurs in a hydrophobic binding site comprising an amphipathic α-helix located in the S5-P linker and the P-S6 linker. In this interaction, the toxins bind in an off-center position in the outer vestibule; however, the lack of the Lys residue found in the functional dyad lead to a reduction but not a total occlusion of K+ current [56].

Figure 7. Schematic representation of Kv modulators binding sites. Purple: ChTx, pore blocker. Orange: HaTx1, gating modifier. A chimeric structure of the channels Kv1.2-2.1 is shown (5WIE). Helices in front and behind the structure were removed for a better appreciation.

3.2. Gating Modifiers Peptides

In contrast to scorpion venom peptides, spider venom peptides are mostly gating modifiers. These peptides range from 29 to 35 residues and were isolated mainly from the venoms of the Theraphosidae family. They are characterized by a promiscuous selectivity between Ca2+, Na+ and K+ channels. For example, the Hanatoxin (HaTx1) [57] and HpTx1 [58] (patent) toxins show effect on Ca2+ and K+ channels. On the other hand, the VsTx1 [59], PaTx1 [60][61], HmTx1 [62][63] and GiTx1 [64] toxins have been reported as Na+ and K+ channel modulators. Furthermore, it has been discovered that in the toxin-channel interaction, the lipids in the cell membrane are also involved [65][66]. For Kv channels, the selectivity of these toxins becomes a little tighter since all of these peptides affect mainly Kv2 and/or Kv4 subfamilies [51]. Although, peptides as the GiTx1 [64] and JZTX-1 [67] have shown an effect on hERG channels.

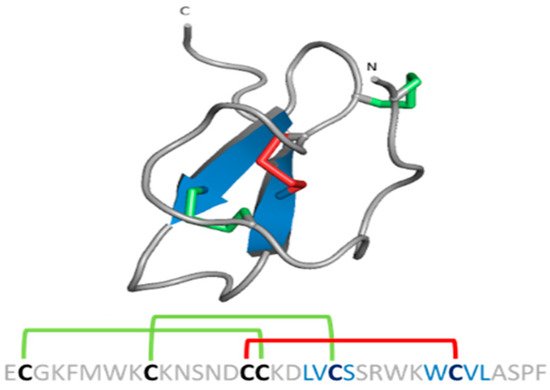

Spider gating modifier peptides present an ICK scaffold, where the β-sheet typically comprises two β strands (a third strand in the N-terminal can be present sometimes) stabilized by a cysteine knot. This knot comprises a ring formed by two disulfides and the intervening polypeptide backbone, with a third disulfide bridge going through the ring to create a pseudo-knot (Figure 8) [68]. The ICK turns these peptides into hyperstable proteins with tremendous chemical, thermal and biological stability [69].

Figure 8. ICK scaffold in peptide gating modifiers. Sequence and structure of the VsTx1 toxin. Disulfide bridge ring is shown in green.

Mechanism of Action of the Gating Modifiers

Spider gating modifier peptides bind to a region of the channel that changes conformation during gating and influences the gating mechanism by altering the relative stability of closed, open or inactivated states [70]. Most of the peptides possess a cluster of solvent-exposed hydrophobic residues (hydrophobic patch) surrounded by highly polar residues (charge belt), enhancing the affinity for the Kv channels by allowing the toxins to partition into the membrane [71]. These peptides interact with the Kv channel in the VSD region, specifically with the paddle motif, a mobile helix-turn-helix motif composed of the C-terminal portion of S3, and the S4 helix (Figure 7). The specific interactions have been revealed for several toxins. For example, in the binding between the HaTx1 and the Kv2.1 channel, the interaction with the F274 and E277 in the C-terminal portion of S3 plays a crucial role [72]. These molecular determinants are shared for the JZTX-XI toxin and the Kv2.1 channel interaction [73] and possibly for the interaction between the JZTX toxins and the hERG channels since the binding sites in the paddle motif of Kv2.1 (I273, F274 and E277) are conserved in the paddle motif of the hERG channel (I512, F513 and E518) [67]. On the other hand, despite HpTx2 binding to the same paddle motif in the Kv4 channel, HpTx2 binding does not require a charged amino acid for the interaction since hydrophobic residues (L275 and V276) are the most important for the binding [74]. Moreover, in experiments using chimera constructs in which the linker region S3-S4 of the Kv2.1 channel (TLTx1-insensitive) was replaced by the corresponding Kv4.2 domain, it was observed that the Kv2.1 channel became sensitive to TLTx1 [75]. These data suggest that even if toxins share the same binding site (paddle motif), the molecular determinants for the interaction can change between different families of Kv channels.

4. Osu1 and Ts6: The Known Peptide Modulators of the Kv1.5

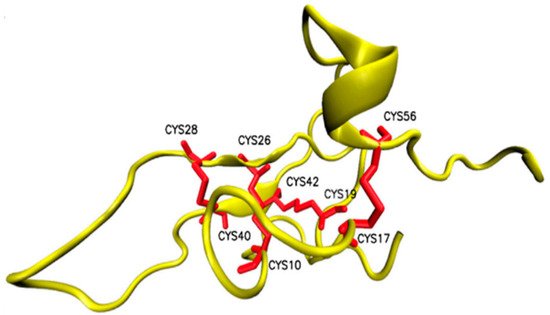

Osu1 is a peptide isolated from the venom of a tarantula, called Oculicosa supermirabilis. It is a 64 amino acid peptide with a mass of 7478 Da, and its spatial structure is formed by four disulfide bridges (Figure 9) [76]. Electrophysiological recordings showed that the total venom of Oculicosa supermirabilis, as well as the native and recombinant Osu1, slowed the activation kinetics of the Kv1.5 current at ~μM peptide concentration. The slowing of the activation kinetics of the current was consistent with a ~40 mV shift in the conductance vs. membrane potential (G-V) relationship of the Osu1 bound channels, as compared to the toxin-free clontrol. In other words, the membrane potential at which 50% of the Kv1.5 channels are open (V1/2) is about 40 mV more positive when Osu1 is present. This rightward shift in the G-V indicates that Osu1 is most likely not bound to the pore of Kv1.5 but rather to the VSD, hindering its movement at depolarization; thus, Kv1.5 opens only at more positive voltages. As a result, in a certain membrane potential range, especially at mild depolarizations close to the activation threshold of the channel, the binding of Osu1 to the voltage sensor appears as an inhibitory effect. Based on this, it is possible to reduce the IKur current through Kv1.5 using Osu1 and thereby influence the shape and duration of the AP in the atrium of the heart.

Figure 9. Structure of Osu1 peptide based on homology model.

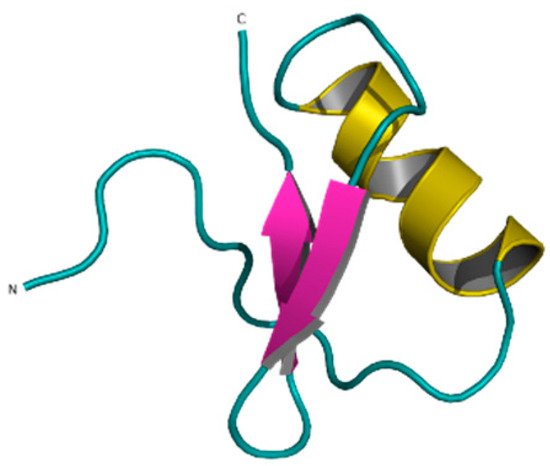

Ts6 (α-KTx 12.1), previously known as butantoxin, also known as TsTX-IV, is the other known Kv1.5 modulating peptide. This peptide was isolated from the venom of the scorpion Tityus serrulatus. It consists of 40 amino acids with a molecular mass of 4506 Da and with 8 cysteine residues (Figure 10) [77][78][79].

Figure 10. Ts6 toxin (1C56).

References

- Olson, T.M.; Alekseev, A.E.; Liu, X.K.; Park, S.; Zingman, L.; Bienengraeber, M.; Sattiraju, S.; Ballew, J.D.; Jahangir, A.; Terzic, A. Kv1.5 channelopathy due to KCNA5 loss-of-function mutation causes human atrial fibrillation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006, 15, 2185–2191.

- Christophersen, I.E.; Olesen, M.S.; Liang, B.; Andersen, M.N.; Larsen, A.P.; Nielsen, J.B.; Haunsø, S.; Olesen, S.-P.; Tveit, A.; Svendsen, J.H.; et al. Genetic variation in KCNA5: Impact on the atrial-specific potassium current IKur in patients with lone atrial fibrillation. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 1517–1525.

- Remillard, C.V.; Tigno, D.D.; Platoshyn, O.; Burg, E.D.; Brevnova, E.E.; Conger, D.; Nicholson, A.; Rana, B.K.; Channick, R.N.; Rubin, L.J.; et al. Function of Kv1.5 channels and genetic variations ofKCNA5in patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2007, 292, C1837–C1853.

- Fu, L.; Lv, Y.; Zhong, Y.; He, Q.; Liu, X.; Du, L. Tyrosine phosphorylation of Kv1.5 is upregulated in intrauterine growth retardation rats with exaggerated pulmonary hypertension. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2017, 50, e6237.

- Macfarlane, S.N.; Sontheimer, H. Modulation of Kv1.5 Currents by Src Tyrosine Phosphorylation: Potential Role in the Differentiation of Astrocytes. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 5245–5253.

- Preussat, K.; Beetz, C.; Schrey, M.; Kraft, R.; Wölfl, S.; Kalff, R.; Patt, S. Expression of voltage-gated potassium channels Kv1.3 and Kv1.5 in human gliomas. Neurosci. Lett. 2003, 346, 33–36.

- Bielanska, J.; Hernandez-Losa, J.; Perez-Verdaguer, M.; Moline, T.; Somoza, R.; Cajal, S.R.Y.; Condom, E.; Ferreres, J.C.; Felipe, A. Voltage-dependent potassium channels Kv1.3 and Kv1.5 in human cancer. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2009, 9, 904–914.

- Vallejo-Gracia, A.; Bielanska, J.; Hernández-Losa, J.; Castellví, J.; Ruiz-Marcellan, M.C.; Cajal, S.R.Y.; Condom, E.; Manils, J.; Soler, C.; Comes, N.; et al. Emerging role for the voltage-dependent K+ channel Kv1.5 in B-lymphocyte physiology: Expression associated with human lymphoma malignancy. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2013, 94, 779–789.

- Chung, M.K.; Eckhardt, L.L.; Chen, L.Y.; Ahmed, H.M.; Gopinathannair, R.; Joglar, J.A.; Noseworthy, P.A.; Pack, Q.R.; Sanders, P.; Trulock, K.M. Lifestyle and Risk Factor Modification for Reduction of Atrial Fibrillation: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020, 141, e750–e772.

- Conen, D. Epidemiology of atrial fibrillation. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 1323–1324.

- Guo, X.; Chen, W.; Sun, H.; You, Q. Kv1.5 Inhibitors for Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation: A Tradeoff between Selectivity and Non-selectivity. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2016, 16, 1843–1854.

- Gutman, G.A.; Chandy, K.G.; Grissmer, S.; Lazdunski, M.; McKinnon, D.; Pardo, L.; Robertson, G.A.; Rudy, B.; Sanguinetti, M.C.; Stühmer, W.; et al. International Union of Pharmacology. LIII. Nomenclature and Molecular Relationships of Voltage-Gated Potassium Channels. Pharmacol. Rev. 2005, 57, 473–508.

- Wettwer, E.; Terlau, H. Pharmacology of voltage-gated potassium channel Kv1.5—Impact on cardiac excitability. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2014, 15, 115–121.

- Attali, B.; Chandy, K.G.; Giese, M.H.; Grissmer, S.; Gutman, G.A.; Jan, L.Y.; Lazdunski, M.; McKinnon, D.; Nerbonne, J.; Pardo, L.A.; et al. Voltage-gated potassium channels (version 2019.4) in the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to Pharmacology Database. IUPHAR/BPS Guide Pharmacol. CITE 2019, 2019.

- Bajaj, S.; Han, J. Venom-Derived Peptide Modulators of Cation-Selective Channels: Friend, Foe or Frenemy. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 58.

- Wirth, K.J.; Paehler, T.; Rosenstein, B.; Knobloch, K.; Maier, T.; Frenzel, J.; Brendel, J.; Busch, A.E.; Bleich, M. Atrial effects of the novel K+-channel-blocker AVE0118 in anesthetized pigs. Cardiovasc. Res. 2003, 60, 298–306.

- Christ, T.; Wettwer, E.; Voigt, N.; Hála, O.; Radicke, S.; Matschke, K.; Várro, A.; Dobrev, D.; Ravens, U. Pathology-specific effects of the IKur/Ito/IK,ACh blocker AVE0118 on ion channels in human chronic atrial fibrillation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 154, 1619–1630.

- Wettwer, E.; Hála, O.; Christ, T.; Heubach, J.F.; Dobrev, D.; Knaut, M.; Varró, A.; Ravens, U. Role of IKur in controlling action potential shape and contractility in the human atrium: Influence of chronic atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2004, 110, 2299–2306.

- Wirth, K.J.; Steinmeyer, K.; Ruetten, H. Sensitization of Upper Airway Mechanoreceptors as a New Pharmacologic Principle to Treat Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Investigations with AVE0118 in Anesthetized Pigs. Sleep 2013, 36, 699–708.

- Shunmugam, S.R.; Sugihara, C.; Freemantle, N.; Round, P.; Furniss, S.; Sulke, N. A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, cross-over study assessing the use of XEN-D0103 in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and implanted pacemakers allowing continuous beat-to-beat monitoring of drug efficacy. J. Interv. Card. Electrophysiol. 2018, 51, 191–197.

- Lagrutta, A.; Wang, J.; Fermini, B.; Salata, J.J. Novel, potent inhibitors of human Kv1.5 K+ channels and ultrarapidly activating delayed rectifier potassium current. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006, 317, 1054–1063.

- Fedida, D.; Orth, P.M.; Chen, J.Y.; Lin, S.; Plouvier, B.; Jung, G.; Ezrin, A.M.; Beatch, G.N. The Mechanism of Atrial Antiarrhythmic Action of RSD1235. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2005, 16, 1227–1238.

- Wettwer, E.; Christ, T.; Endig, S.; Rozmaritsa, N.; Matschke, K.; Lynch, J.J.; Pourrier, M.; Gibson, J.K.; Fedida, D.; Knaut, M.; et al. The new antiarrhythmic drug vernakalant: Ex vivo study of human atrial tissue from sinus rhythm and chronic atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2013, 98, 145–154.

- Dobrev, D.; Hamad, B.; Kirkpatrick, P. Vernakalant. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010, 9, 915–916.

- Burashnikov, A.; Pourrier, M.; Gibson, J.K.; Lynch, J.J.; Antzelevitch, C. Rate-dependent effects of vernakalant in the isolated non-remodeled canine left atria are primarily due to block of the sodium channel: Comparison with ranolazine and dl-sotalol. Circ. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2012, 5, 400–408.

- van Middendorp, L.B.; Strik, M.; Houthuizen, P.; Kuiper, M.; Maessen, J.G.; Auricchio, A.; Prinzen, F.W. Electrophysiological and haemodynamic effects of vernakalant and flecainide in dyssynchronous canine hearts. Europace 2014, 16, 1249–1256.

- Camm, A.J.; Capucci, A.; Hohnloser, S.H.; Torp-Pedersen, C.; Van Gelder, I.C.; Mangal, B.; Beatch, G. A Randomized Active-Controlled Study Comparing the Efficacy and Safety of Vernakalant to Amiodarone in Recent-Onset Atrial Fibrillation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 57, 313–321.

- Cialdella, P.; Pedicino, D.; Santangeli, P. Novel Agents for the Acute Conversion of Atrial Fibrillation: Focus on Vernakalant. Recent Patents Cardiovasc. Drug Discov. 2011, 6, 1–8.

- Simon, A.; Niederdoeckl, J.; Janata, K.; Spiel, A.O.; Schuetz, N.; Schnaubelt, S.; Herkner, H.; Cacioppo, F.; Laggner, A.N.; Domanovits, H. Vernakalant and electrical cardioversion for AF–Safe and effective. IJC Heart Vasc. 2019, 24, 100398.

- Hall, A.J.; Mitchell, A. Introducing Vernakalant into Clinical Practice. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. Rev. 2019, 8, 70–74.

- Bergeron, Z.L.; Bingham, J.P. Scorpion toxins specific for potassium (K+) channels: A historical overview of peptide bioengineering. Toxins 2012, 4, 1082–1119.

- Rash, L.; Hodgson, W.C. Pharmacology and biochemistry of spider venoms. Toxicon 2002, 40, 225–254.

- King, G.F.; Gentz, M.C.; Escoubas, P.; Nicholson, G.M. A rational nomenclature for naming peptide toxins from spiders and other venomous animals. Toxicon 2008, 52, 264–276.

- Jungo, F.; Bairoch, A. Tox-Prot, the toxin protein annotation program of the Swiss-Prot protein knowledgebase. Toxicon 2005, 45, 293–301.

- Jungo, F.; Estreicher, A.; Bairoch, A.; Bougueleret, L.; Xenarios, I. Animal Toxins: How is Complexity Represented in Databases? Toxins 2010, 2, 262–282.

- Jungo, F.; Bougueleret, L.; Xenarios, I.; Poux, S. The UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot Tox-Prot program: A central hub of integrated venom protein data. Toxicon 2012, 60, 551–557.

- Quintero-Hernández, V.; Jiménez-Vargas, J.; Gurrola, G.; Valdivia, H.; Possani, L. Scorpion venom components that affect ion-channels function. Toxicon 2013, 76, 328–342.

- Kuzmenkov, A.I.; Krylov, N.; Chugunov, A.O.; Grishin, E.V.; Vassilevski, A.A. Kalium: A database of potassium channel toxins from scorpion venom. Database 2016, 2016, baw056.

- Tytgat, J.; Chandy, K.G.; Garcia, M.L.; Gutman, G.A.; Martin-Eauclaire, M.F.; van der Walt, J.J.; Possani, L.D. A unified nomenclature for short-chain peptides isolated from scorpion venoms: Alpha-KTx molecular subfamilies. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1999, 20, 444–447.

- de la Vega, R.C.R.; Possani, L.D. Current views on scorpion toxins specific for K+-channels. Toxicon 2004, 43, 865–875.

- Zhu, S.; Gao, B.; Aumelas, A.; Rodríguez, M.D.C.; Lanz-Mendoza, H.; Peigneur, S.; Diego-Garcia, E.; Martin-Eauclaire, M.-F.; Tytgat, J.; Possani, L.D. MeuTXKβ1, a scorpion venom-derived two-domain potassium channel toxin-like peptide with cytolytic activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Proteins Proteom. 2010, 1804, 872–883.

- Kuzmenkov, A.I.; Grishin, E.V.; Vassilevski, A.A. Diversity of Potassium Channel Ligands: Focus on Scorpion Toxins. Biochemistry 2015, 80, 1764–1799.

- Bartok, A.; Panyi, G.; Varga, Z. Potassium Channel Blocking Peptide Toxins from Scorpion Venom. In Scorpion Venoms; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 493–527.

- Diego-García, E.; Schwartz, E.F.; D’Suze, G.; González, S.A.R.; Batista, C.V.; García, B.I.; de la Vega, R.C.R.; Possani, L.D. Wide phylogenetic distribution of Scorpine and long-chain beta-KTx-like peptides in scorpion venoms: Identification of “orphan” components. Peptides 2007, 28, 31–37.

- Jiménez-Vargas, J.; Restano-Cassulini, R.; Possani, L. Toxin modulators and blockers of hERG K+ channels. Toxicon 2012, 60, 492–501.

- Corona, M.; Gurrola, G.B.; Merino, E.; Cassulini, R.R.; Valdez-Cruz, N.A.; García, B.; Ramírez-Domínguez, M.E.; Coronas, F.I.; Zamudio, F.Z.; Wanke, E.; et al. A large number of novel Ergtoxin-like genes and ERG K+-channels blocking peptides from scorpions of the genus Centruroides. FEBS Lett. 2002, 532, 121–126.

- Chagot, B.; Pimentel, C.; Dai, L.; Pil, J.; Tytgat, J.; Nakajima, T.; Corzo, G.; Darbon, H.; Ferrat, G. An unusual fold for potassium channel blockers: NMR structure of three toxins from the scorpion Opisthacanthus madagascariensis. Biochem. J. 2005, 388, 263–271.

- Zhao, R.; Dai, H.; Qiu, S.; Li, T.; He, Y.; Ma, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wu, Y.; Li, W.; Cao, Z. SdPI, The First Functionally Characterized Kunitz-Type Trypsin Inhibitor from Scorpion Venom. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e27548.

- Chen, Z.-Y.; Hu, Y.-T.; Yang, W.-S.; He, Y.-W.; Feng, J.; Wang, B.; Zhao, R.-M.; Ding, J.-P.; Cao, Z.-J.; Li, W.-X.; et al. Hg1, Novel Peptide Inhibitor Specific for Kv1.3 Channels from First Scorpion Kunitz-type Potassium Channel Toxin Family. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 13813–13821.

- Cremonez, C.M.; Maiti, M.; Peigneur, S.; Cassoli, J.S.; Dutra, A.A.A.; Waelkens, E.; Lescrinier, E.; Herdewijn, P.; De Lima, M.E.; Pimenta, A.M.C.; et al. Structural and Functional Elucidation of Peptide Ts11 Shows Evidence of a Novel Subfamily of Scorpion Venom Toxins. Toxins 2016, 8, 288.

- Jiménez-Vargas, J.M.; Possani, L.D.; Luna-Ramírez, K. Arthropod toxins acting on neuronal potassium channels. Neuropharmacology 2017, 127, 139–160.

- Gao, B.; Harvey, P.J.; Craik, D.J.; Ronjat, M.; De Waard, M.; Zhu, S. Functional evolution of scorpion venom peptides with an inhibitor cystine knot fold. Biosci. Rep. 2013, 33, 513–527.

- Banerjee, A.; Lee, A.; Campbell, E.B.; MacKinnon, R. Structure of a pore-blocking toxin in complex with a eukaryotic voltage-dependent K+ channel. eLife 2013, 2, e00594.

- Mouhat, S.; Mosbah, A.; Visan, V.; Wulff, H.; Delepierre, M.; Darbon, H.; Grissmer, S.; De Waard, M.; Sabatier, J.-M. The functional dyad of scorpion toxin Pi1 is not itself a prerequisite for toxin binding to the voltage-gated Kv1.2 potassium channels. Biochem. J. 2004, 377, 25–36.

- Cui, M.; Shen, J.; Briggs, J.M.; Fu, W.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, X.; Chi, Z.; Ji, R.; Jiang, H.; et al. Brownian dynamics simulations of the recognition of the scorpion toxin P05 with the small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. J. Mol. Biol. 2002, 318, 417–428.

- Pardo-Lopez, L.; Zhang, M.; Liu, J.; Jiang, M.; Possani, L.D.; Tseng, G.N. Mapping the binding site of a human ether-a-go-go-related gene-specific peptide toxin (ErgTx) to the channel’s outer vestibule. J. Mol. Biol. 2002, 277, 16403–16411.

- Li-Smerin, Y.; Swartz, K.J. Gating modifier toxins reveal a conserved structural motif in voltage-gated Ca2+ and K+ channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 8585–8589.

- Sanguinetti, M.C.; Johnson, J.H.; Hammerland, L.G.; Kelbaugh, P.R.; Volkmann, R.A.; Saccomano, N.A.; Mueller, A.L. Heteropodatoxins: Peptides isolated from spider venom that block Kv4.2 potassium channels. Mol. Pharmacol. 1997, 51, 491–498.

- Redaelli, E.; Cassulini, R.R.; Silva, D.F.; Clement, H.; Schiavon, E.; Zamudio, F.Z.; Odell, G.; Arcangeli, A.; Clare, J.J.; Alagón, A.; et al. Target Promiscuity and Heterogeneous Effects of Tarantula Venom Peptides Affecting Na+ and K+ Ion Channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 4130–4142.

- Diochot, S.; Drici, M.-D.; Moinier, D.; Fink, M.; Lazdunski, M. Effects of phrixotoxins on the Kv4 family of potassium channels and implications for the role of Ito1 in cardiac electrogenesis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999, 126, 251–263.

- Park, J.H.; Carlin, K.P.; Wu, G.; Ilyin, V.I.; Musza, L.L.; Blake, P.R.; Kyle, D.J. Studies Examining the Relationship between the Chemical Structure of Protoxin II and Its Activity on Voltage Gated Sodium Channels. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 6623–6631.

- Escoubas, P.; Diochot, S.; Célérier, M.L.; Nakajima, T.; Lazdunski, M. Novel tarantula toxins for subtypes of voltage-dependent potassium channels in the Kv2 and Kv4 subfamilies. Mol. Pharmacol. 2002, 62, 48–57.

- Osteen, J.D.; Herzig, V.; Gilchrist, J.; Emrick, J.J.; Zhang, C.; Wang, X.; Castro, J.; Garcia-Caraballo, S.; Grundy, L.; Rychkov, G.Y.; et al. Selective spider toxins reveal a role for the Nav1.1 channel in mechanical pain. Nature 2016, 534, 494–499.

- Montandon, G.G.; Cassoli, J.S.; Peigneur, S.; Verano-Braga, T.; dos Santos, D.M.; Paiva, A.L.B.; de Moraes, É.R.; Kushmerick, C.; Borges, M.H.; Richardson, M.; et al. GiTx1(β/κ-theraphotoxin-Gi1a), a novel toxin from the venom of Brazilian tarantula Grammostola iheringi (Mygalomorphae, Theraphosidae): Isolation, structural assessments and activity on voltage-gated ion channels. Biochimie 2020, 176, 138–149.

- Lee, S.-Y.; MacKinnon, R. A membrane-access mechanism of ion channel inhibition by voltage sensor toxins from spider venom. Nature 2004, 430, 232–235.

- Wee, C.L.; Bemporad, D.; Sands, Z.A.; Gavaghan, D.; Sansom, M.S. SGTx1, a Kv Channel Gating-Modifier Toxin, Binds to the Interfacial Region of Lipid Bilayers. Biophys. J. 2007, 92, L07–L09.

- Wang, Y.; Luo, Z.; Lei, S.; Li, S.; Li, X.; Yuan, C. Effects and mechanism of gating modifier spider toxins on the hERG channel. Toxicon 2021, 189, 56–64.

- Saez, N.J.; Senff, S.; Jensen, J.E.; Er, S.Y.; Herzig, V.; Rash, L.D.; King, G.F. Spider-Venom Peptides as Therapeutics. Toxins 2010, 2, 2851–2871.

- Colgrave, M.L.; Craik, D.J. Thermal, Chemical, and Enzymatic Stability of the Cyclotide Kalata B1: The Importance of the Cyclic Cystine Knot. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 5965–5975.

- Swartz, K.J. Tarantula toxins interacting with voltage sensors in potassium channels. Toxicon 2007, 49, 213–230.

- Ozawa, S.-I.; Kimura, T.; Nozaki, T.; Harada, H.; Shimada, I.; Osawa, M. Structural basis for the inhibition of voltage-dependent K+ channel by gating modifier toxin. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14226.

- Li-Smerin, Y.; Swartz, K.J. Localization and Molecular Determinants of the Hanatoxin Receptors on the Voltage-Sensing Domains of a K+ Channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 2000, 115, 673–684.

- Tao, H.; Chen, X.; Deng, M.; Xiao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, S.; He, Y.; Liang, S. Interaction site for the inhibition of tarantula Jingzhaotoxin-XI on voltage-gated potassium channel Kv2.1. Toxicon 2016, 124, 8–14.

- DeSimone, C.V.; Lu, Y.; Bondarenko, V.E.; Morales, M.J. S3b Amino Acid Substitutions and Ancillary Subunits Alter the Affinity of Heteropoda venatoria Toxin 2 for Kv4.3. Mol. Pharmacol. 2009, 76, 125–133.

- Ebbinghaus, J.; Legros, C.; Nolting, A.; Guette, C.; Celerier, M.-L.; Pongs, O.; Bähring, R. Modulation of Kv4.2 channels by a peptide isolated from the venom of the giant bird-eating tarantula Theraphosa leblondi. Toxicon 2004, 43, 923–932.

- Alvarado, D.; Cardoso-Arenas, S.; Corrales-García, L.-L.; Clement, H.; Arenas, I.; Montero-Dominguez, P.A.; Olamendi-Portugal, T.; Zamudio, F.; Csoti, A.; Borrego, J.; et al. A Novel Insecticidal Spider Peptide that Affects the Mammalian Voltage-Gated Ion Channel hKv1.5. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11, 1937.

- Cerni, F.A.; Pucca, M.B.; Peigneur, S.; Cremonez, C.M.; Bordon, K.C.F.; Tytgat, J.; Arantes, E.C. Electrophysiological Characterization of Ts6 and Ts7, K+ Channel Toxins Isolated through an Improved Tityus serrulatus Venom Purification Procedure. Toxins 2014, 6, 892–913.

- Martin-Eauclaire, M.F.; Pimenta, A.M.; Bougis, P.E.; De Lima, M.E. Potassium channel blockers from the venom of the Brazilian scorpion Tityus serrulatus (Lutz and Mello, 1922). Toxicon 2016, 119, 253–265.

- Zoccal, K.F.; da Silva Bitencourt, C.; Sorgi, C.A.; Bordon, K.D.C.F.; Sampaio, S.V.; Arantes, E.C.; Faccioli, L.H. Ts6 and Ts2 from Tityus serrulatus venom induce inflammation by mechanisms dependent on lipid mediators and cytokine production. Toxicon 2013, 61, 1–10.

More

Information

Subjects:

Biology; Biophysics; Physiology

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

2.0K

Entry Collection:

Peptides for Health Benefits

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

30 Dec 2021

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No