| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dennis Özcelik | + 3992 word(s) | 3992 | 2021-05-08 08:15:33 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | Meta information modification | 3992 | 2021-05-20 08:03:47 | | | | |

| 3 | Peter Tang | Meta information modification | 3992 | 2021-05-20 08:07:32 | | |

Video Upload Options

Inflammation is one key process in driving cellular redox homeostasis toward oxidative stress, which perpetuates inflammation. In the brain, this interplay results in a vicious cycle of cell death, the loss of neurons, and leakage of the blood–brain barrier. Hence, the neuroinflammatory response fuels the development of acute and chronic inflammatory diseases. Interrogation of the interplay between inflammation, oxidative stress, and cell death in neurological tissue in vivo is very challenging. The complexity of the underlying biological process and the fragility of the brain limit our understanding of the cause and the adequate diagnostics of neuroinflammatory diseases. Notable redox biomarkers for imaging with positron emission tomography (PET) tracers are the 18 kDa translocator protein (TSPO) and monoamine oxygenase B (MAO–B).

1. Introduction

Neuroinflammation is a complex and poorly understood phenomenon with high clinical relevance. A large number of disorders of the central nervous system (CNS) show a substantial neuroinflammatory component. Notable examples are neuropsychiatric diseases, such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder [1][2][3]. Inflammatory processes also play an important role in many autoimmune disorders of the CNS, of which multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common one [4]. Despite the rapidly increasing incidence, the cause of MS is still under debate [5]. It is clear, however, that the immune system eliminates the myelin layers of nerve fibers [6]. These continuous attacks result in local inflammation sites within the myelin sheath and, eventually, recognizable lesions in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. These inflammation events disrupt the neuronal networks and, hence, are responsible for a highly diverse array of symptoms. Neurodegenerative diseases are another group of CNS disorders that display chronic inflammation of the brain. A notable representative of this group is Alzheimer’s disease (AD), which is also the leading cause of dementia [7].

A growing body of research provides evidence for chronic neuroinflammation as a cause for AD development, which is comprehensively summarized elsewhere [8][9]. For example, a number of studies found an elevated level of inflammation markers, e.g., the cytokines interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), in mouse models and AD patients [8][10][11][12]. Another study demonstrated that the innate immunity protein interferon-induced transmembrane protein 3 (IFITM3) is associated with Aβ production [13]. This study also linked the age-dependent increase of inflammatory markers, such as type I interferons [14], to concomitantly increased IFITM3 levels in the elderly, ultimately matching the clinical manifestation of AD as a late-developing neurological disease. Other studies showed that anti-inflammatory molecules enhance [15], or that proinflammatory molecules decrease Aβ clearance by the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM-2) [16][17][18]. We refer the interested reader to the up-to-date review from Shi and Holtzman on the role of TREM-2, APOE, and disease-associated microglia in inflammation in AD [19].

In contrast to AD and other neurodegenerative diseases, which are associated with chronic inflammation, ischemic stroke is a representative example of a pathology that is associated with acute inflammation [20]. In ischemic stroke, occlusion of, usually, the middle cerebral artery reduces or blocks the blood flow in the human brain, which causes hypoxia in cortical brain areas [21]. Low oxygen levels trigger a vast and complex biochemical cascade encompassing inflammation, which finally causes neuronal cell death and impaired brain function [22].

A major factor for neuronal cell death in inflammation is oxidative stress. Oxidative stress is characterized by a relative increase of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which leads to an imbalance of the tightly regulated redox homeostasis of the cell [23][24]. This imbalance jeopardizes cellular function and survival, because ROS can react with a wide variety of biological biomolecules, causing, for instance, DNA damage [25] and protein modification [26], and eventually leading to apoptosis [27]. Moreover, ROS and oxidative stress can activate inflammatory signaling pathways and, hence, induce the production of numerous proinflammatory cytokines that drive inflammation [28]. Proinflammatory cytokines activate immune cells, amplifying both inflammation and ROS generation. Hence, the neuroinflammatory response fuels oxidative stress, which perpetuates inflammation.

Initial causes of the inflammatory responses and oxidative stress are perturbation in the cellular metabolism due to genetic anomalies or environmental factors. Typical examples of such environmental factors comprise lifestyle choices, for instance, physical exercise, diet, smoking, and alcohol consumption [29][30]. Consequently, these factors correlate with the development of stroke [31][32][33], neurodegenerative disorders [34][35], and other inflammatory brain diseases [36][37]. Other known external factors are pathogens, e.g., viruses and bacteria [38], and physical injuries, e.g., traumatic brain injury [39]. Environmental pollutants are another important factor that is connected to inflammation [40]. Many pollutants, e.g., metals [41], pesticides [42][43][44], and microplastic [45][46], are suspected to impair well-being. Furthermore, a large amount of research has established over the years that air pollution is associated with inflammatory processes in the body, including the brain [47][48][49]. For instance, a very recent study showed a correlation between air quality and the development of neurodegeneration [50].

In order to diagnose and treat many CNS diseases, it is crucial to understand, assess, and monitor the neuroinflammatory response in the brain. This, however, is a major challenge because of the complexity of the underlying biochemical processes of inflammation, particularly in the brain. Consequently, a lack of tools prohibits interrogating neuroinflammatory components and pathways for diagnostic and clinical purposes. The advent of chemical and synthetic biology might provide the research community and clinical professionals with novel means to trace the development of inflammatory processes in the human brain.

2. Redox Biology of Inflammation

2.1. Interplay of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation

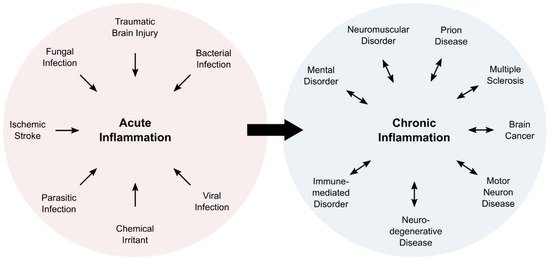

Inflammation is a complex physiological process, which is associated with five characteristic symptoms: pain, redness, swelling, heat, and loss of function. Typically, inflammatory processes can be classified as acute or chronic inflammation (Figure 1). Acute inflammation is a direct response of the body and fades within a limited amount of time, usually within a few days. Subacute inflammation persists up to six weeks, whereas longer periods are deemed chronic. Chronic inflammation can last for years, and is associated with numerous pathologies (Figure 1).

Upon exposure to a pathogen, an irritant, or cell damage, leukocytes enter the affected tissue in order to eliminate the intruding pathogen, limit propagation of damage, and stimulate tissue repair processes [51]. Cells in the surrounding area secrete cytokines, in particular, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, to further attract and to activate cells of the immune system from the bloodstream or the local tissue [52][53]. An important effect of the inflammatory response is the alteration of redox environment [54][55].

The redox environment is tightly regulated to enable controlled biochemical reactions and molecular interactions in the cell and the organism [23][56][57][58]. In this environment, oxygen very often takes the prominent role as the terminal electron acceptor. The electron transfer to oxygen results in by-products, in particular, ROS that include superoxide anion (O2•−), hydroxyl radical (OH•), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Naturally, cells produce a basal level of ROS in the mitochondria, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and the peroxisomes [59]. The major sources of intracellular ROS in these organelles are nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidases (NOXs), mitochondrial electron transport chains, as well as ER oxidoreductases [60][61][62]. Under normal conditions, the cell is able to contain ROS, but overproduction leads to oxidative stress that impairs other physiological pathways [24][63].

A large number of studies established the interlocked nature of inflammation and oxidative stress. For instance, ROS regulate T cell responses, which indicates that oxidative stress can trigger an erroneous immune response, which fuels ongoing immune reactions [64][65]. In addition, ROS react with redox-sensitive proteins in the cell, and thus modulate crucial inflammatory signaling pathways, such as the MAPK/ERK pathway [66][67][68] or the NF-κB pathway [69][70][71]. Another important example of the interplay of oxidative stress and inflammation is the induction of the “respiratory burst” in phagocytic cells of the immune system, e.g., neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages. This rapid production of ROS and other radicals, such as nitric oxide (NO•), serves to eliminate the pathogen and to stimulate the cytokine response by the leukocytes [72][73]. The central component of the increased ROS production is the NADPH oxidase 2, which is also termed NOX2 in humans [74][75]. NOX2 is present in multiple cell types and is responsible for the production of constitutive but low levels of ROS. During the respiratory burst, however, NOX2 activity increases substantially in phagocytes, which is associated with an up to 100-fold increase in oxygen consumption, and causes the physiologically induced oxidative stress event [76][77].

A large body of research provides compelling evidence for the important contribution of both oxidative stress and inflammation to the development of pathogen-independent inflammatory diseases, such as cancer, diabetes, or neurodegenerative diseases [78][79]. If left unchecked, inflammation and oxidative stress mutually perpetuate each other, driving the affected tissue in a vicious cycle to massive damage. Hence, the interplay of the redox landscape and inflammation draws considerable attention in current research efforts.

2.2. Induction of the Inflammatory Response

Activation of inflammatory signaling pathways is facilitated by various signals that also include oxidative stress. Upon recognition of an external stimulus, the innate immune system induces an inflammatory response. This recognition is mediated by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that sense pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). Besides membrane-bound PPRs, e.g., the Toll-like receptors (TLRs), that sense extracellular or endosomal signals, intracellular PPRs, including the nucleotide-binding domain and leucine-rich repeat-containing receptors (NLRs), and absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2)-like receptors (ALRs), recognize intracellular signals. A subgroup of cytosolic PPRs contributes to the assembly of the inflammasome [80]. The inflammasome is an intracellular multiprotein complex that activates and secretes the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1b and IL-18 [81]. Inflammasome activation depends on a number of factors, and ROS are known modulators of inflammasome activity [82].

It has been shown that H2O2 produced by the mitochondrial enzyme monoamine oxidase B (MAO–B) is crucially involved in the activation of the inflammasome [83]. This remarkable study also suggested that MAO–B could be exploited as a target for therapeutic modulation of inflammatory signaling. Besides direct modulation of inflammasomal activity, redox signaling can also indirectly regulate the inflammasome. For instance, an earlier study showed that liposomes could activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, which involves ROS and ROS-dependent calcium influx [84]. A more recent study showed that the 18 kDa translocator protein (TSPO), located in the outer mitochondrial membrane, is a key regulator of calcium homeostasis [85]. Since calcium signaling and mitochondrial destabilization induce the NLRP3 inflammasome [86], it seems to be plausible that TSPO contributes to the regulation of inflammasomal activity.

The activity of the inflammasome induces an inflammatory cascade that results in pyroptosis, a certain type of programmed cell death [87]. Pyroptosis requires activation of caspases, e.g., caspase-1, and stimulates the production of proinflammatory cytokines and gasdermins [88]. Gasdermins are pore-forming proteins that rupture the cell membrane, enabling the release of cytokines and DAMPs that perpetuate the inflammatory response by recruiting immune cells to the tissue [89][90]. Hence, inflammasomes play a key role in the inflammatory response, and were initially studied in cells of the innate immune system. PPRs are expressed in macrophages, NK cells, neutrophils, mast cells, and other cells of the innate immune system. Nevertheless, a large body of research also described inflammasomes in epithelial cells [80].

Given the central role in the inflammatory response, the inflammasome has drawn considerable attention as a drug target to tackle inflammatory diseases [91]. Inflammasome activation and cytokines production have been targeted by antagonists of the IL-1 receptor (e.g., anakinra), IL-1b neutralizing antibodies (e.g., canakinumab), and soluble decoy receptors for IL-1b and IL-1a (e.g., rilonacept) [92]. In addition, several compounds have been described for targeting subunits of the inflammasomes, such as NLRP3, caspase-1, and gasdermin D [93][94]. Despite all efforts, our current understanding of inflammasome signaling and the inflammatory response is still very limited, particularly in CNS inflammation.

2.3. The Neuroinflammatory Response

The brain, but also the entire central nervous system (CNS), is an immunologically privileged site, and possesses a distinct immune system that protects neuronal cells against pathogens [95][96]. The neuroimmune system comprises the highly diverse group of nonneuronal glial cells, which can roughly be divided into macroglia (e.g., astrocytes, enteric glial cells, ependymal cells, oligodendrocytes, radial glia, satellite cells, and Schwann cells) and microglia [97]. The latter ones are the major components of the neuroimmune system, and act as resident macrophages in the CNS [98]. They also express PPRs [99]; however, inflammatory signaling was also described for neurons [100], astrocytes [101], perivascular CNS macrophages [102], oligodendrocytes [103], and endothelial cells [104].

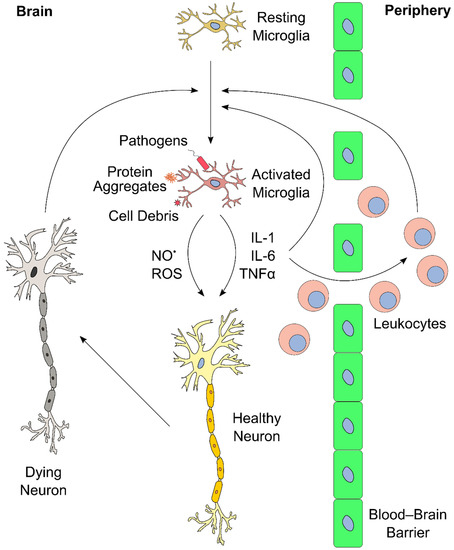

Upon activation, microglia release proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α [52][105][106]. Like the immune cells of the bloodstream, microglia are also capable of undergoing respiratory burst phases that are mediated by an increase in NOX2 activity. ROS production is a crucial tool that microglia utilize in response to pathogens, protein aggregates, or cell debris [107][108]. For more detailed information on ROS generation in microglia, the interested reader is referred to a comprehensive review by Simpson and Oliver [109].

The inflammatory response in the brain and elsewhere is tightly regulated. Limited inflammation can fail to clear an infection, whereas overreaction can induce massive tissue damage [51][110][111]. Similarly, ongoing and chronic inflammation lead to severe side effects and physiological complications. A notable consequence of neuroinflammation affects the blood–brain barrier (BBB) [112]. The BBB consists of a layer of endothelial cells that create a highly selective semipermeable boundary, which separates the CNS from the circulating blood, and protects it from pathogens [113]. The BBB also prevents the passage of antibodies and immune cells. Moreover, the BBB limits the uptake of certain drugs, including antibiotics, to the CNS, making the BBB a considerable obstacle in the treatment of CNS diseases. Neuroinflammation can lead to increased permeability of the BBB, enabling infiltration of leukocytes, which can then participate in perpetuating the inflammatory response [51][111]. An overview of the neuroinflammatory response is presented in Figure 2.

Proinflammatory cytokines directly and indirectly increase neuronal cell damage. For instance, IL-1β causes neurotoxic effects by a variety of pathways [114], including the induction of oxidative stress [115][116]. IL-6 has an important function in neuronal tissue homeostasis, but overproduction leads to neurodegeneration [117][118]. Furthermore, IL-6 also mediates upregulation of VCAM-1 that leads to permeability of the BBB, allowing infiltration of leukocytes [119]. TNF-α recruits leukocytes from the periphery into the brain, and directly affects endothelial cells, eventually leading to increased BBB permeability [120]. In addition, TNF-α potentiates glutamate-induced cell death in hippocampal slides: it inhibits glutamate transporters, increases the expression of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors, and, ultimately, elevates the levels of the oxidative effector nitric oxide synthase, which yields oxidative stress [121].

As illustrated, the redox landscape plays a crucial role in the development and progression of neurological diseases. Hence, experimental and translational methods are necessary to interrogate the progression of inflammatory and oxidative biomarkers in neurological diseases.

3. Tools and Methods to Monitor the Redox Landscape of Neuroinflammation

3.1. Monitoring the Redox Landscape in the Laboratory

Since inflammation and oxidative stress are tightly connected, the monitoring of ROS can provide valuable information about the biological processes during inflammation. One major challenge in this area of research is the limitation of available tools to monitor and to detect oxidative stress and inflammation. Over the years, scientists have developed a plethora of tools to study the production of ROS in cellular models. In general, there are two types of sensors to monitor the redox state in living cellular systems: genetically encoded redox proteins and small-molecule probes. These tools have been described numerous times, and we recommend a selection of comprehensive overviews that provide a detailed summary of genetically encoded redox proteins [122] and small-molecule redox sensors, including recent positron emission tomography (PET) tracers [123][124].

A significant body of research is devoted to the development and improvement of genetically encoded redox proteins. Recent advances led to novel fluorophores, for instance, a fluorescent protein that displays a redox-dependent change from green to blue [125]. Further, many studies reported the development of sensors for specific biomolecules that play an important role in the redox landscape, such as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) [126]. Furthermore, a recent study presented redox sensors for the cytosolic glutathione system, the major antioxidant system of the cell [127]. These genetically encoded redox proteins are very useful for monitoring the redox landscape under experimental conditions [128]. For instance, these sensors enable the study of molecular pathologies in animal models, such as the oxidative stress-mediated neurodegeneration of motor neurons in zebrafish [129]. Unfortunately, redox protein sensors depend on specific model systems, which prevents their application for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes in the human patient.

By contrast, redox sensors based on small molecules can be applied theoretically to humans, since the administration of compounds is not restricted to a defined model organism. Some recent examples include nicotinamide molecules that are conjugated to fluorophores, and serve as effective redox sensors in biological systems [130]. Other advances are multichannel redox sensors that combine chromogenic, fluorescent, and electrochemical signals for monitoring intracellular H2O2 in vivo [131]. However, small-molecule-based redox sensors require a specific chemical interaction between the compound and the target molecule; hence, their application is limited by the availability, selectivity, reversibility, and kinetics of the sensing reaction [123].

Besides the development of novel tools, another promising path for monitoring redox states in cellular model systems is the improvement of imaging devices. One recent example is the development of fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy for single-cell ROS detection (FLIM–ROX) [132]. FLIM has been used before to detect the redox state in cells via reduction of NADH; however, the authors of this study applied FLIM in conjunction with selected ROS reporter dyes. The combination of the dye with the microscopic technique improved the sensitivity and reliability of ROS detection in lifetime imaging.

Research also explores some entirely novel approaches for monitoring oxidative stress in biological systems. A very recent and highly innovative approach to study the redox landscape in vivo in real-time was presented by Baltsavias et al. [133]. This group developed a small implant that is capable of measuring the balance of oxidants and reductants that are produced by the interplay of host, microbe, and diet in the gut. After implanting in rats, the device was powered externally with ultrasonic waves, and was able to monitor the redox state in the gut of the living animal for almost two weeks. This approach enables long-term experimental testing of redox pathophysiology mechanisms, and facilitates translation to disease diagnosis and treatment applications in the future.

3.2. Positron Emission Tomography (PET) for Monitoring Oxidative Stress

Noninvasive imaging methods provide diagnostic and prognostic information on functional states of the brain, and support effectivity assessment of new drug candidates [134][135]. Positron emission tomography (PET) is a molecular imaging modality, in which the administration of a positron emission radiotracer enables visualization and quantification of biochemical processes in vivo [136]. In neuroimaging, this radiotracer is often a small molecule that is labeled with fluorine-18 (half-life of 109.8 min) or carbon-11 (half-life of 20.3 min) radionuclides. An ideal PET radiotracer displays a high signal-to-noise ratio, which is defined as the ratio of specific to nonspecific binding, and increases its signal under a pathological versus a baseline (i.e., physiological) condition. Ideally, this signal also correlates with disease severity and responds to known therapeutic agents.

One proposed strategy for detecting ROS using PET relies on the change in cell permeability of dihydroethidium (DHT) tracers upon oxidation. A neutral fluorine-18 labelled DHT analog is BBB permeable, and becomes positively charged upon reacting with O2•−, trapping it intracellularly [137]. In a lipopolysaccharide (LPS) lesion model, this tracer showed enhanced accumulation in the ipsilateral side of the mouse brain, and the PET signal intensity correlated with the severity of the clinical symptoms [138]. Another family of O2•− sensitive PET tracers is based on the dihydroisoquinoline scaffold. A carbon-11 labeled hydromethidine was initially described to accumulate in the rat brain after a LPS injury [139]. A fluorine-18 analog recently confirmed the retention of the tracer in the affected region [140]. However, this strategy detects only intracellular ROS, since the cationized tracer is only retained if formed inside the cell.

A notable study explored the differential uptake kinetics of oxidized versus reduced ascorbic acid, and overcame this limitation [141]. Ascorbic acid was labeled with carbon-11, and, after reacting with H2O2 or O2•−, it yielded [11C]dehydroascorbic acid ([11C]DHA), which is transported to cells ten times faster than ascorbic acid. Differential uptake of [11C]DHA was demonstrated in both cancer cell lines and also in human neutrophils, validating this approach. Another way of detecting extracellular ROS with PET focuses on the equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (ENT1). Here, the endogenous thymidine substrate was modified with a H2O2 carbamate-boronate-sensitive linker, and labeled with fluorine-18. Upon reaction with H2O2, the linker decomposes, making it a better substrate for ENT1-mediated internalization. Once inside the cell, the thymidine substrate cannot be further metabolized because of the fluorine-18 modification, which impairs enzyme recognition, eventually leading to intracellular tracer accumulation [142]. As a note, this tracer is also cell-permeable via passive diffusion and, hence, reports both intra- and extracellular ROS. The tracer signal responded to H2O2 dose-dependently, and was blocked by co-incubation with high concentrations of thymidine. However, the described applications were limited to cellular carcinoma models, perhaps due to the carbonate linker instability in vivo.

Only a few PET tracers were used in clinical studies to specifically probe redox processes in vivo. One of them is the copper chelator [62/64Cu]Cu-ATSM. After reacting with ROS, the reduced radioactive 62/64Cu+ dissociates from the complex, and is retained in the tissue [143]. This tracer was also applied in neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), as well as in cancer [124][144]. Unlike the previously described tracers, which are reactive toward endogenous ROS, the [18F]fluoropropyl-glutamate tracer [18F]FSPG provides a measure of cellular antioxidant response via imaging a major contributor to the cellular redox homeostasis, i.e., the cystine/glutamate antiporter system xC−. [18F]FSPG is a substrate of system xC−, and cancer cells under oxidative stress upregulate this transporter, which is expressed at a low level in normal cells [145][146]. In a recent clinical trial, [18F]FSPG PET was used for the diagnosis of prostate cancer, confirming the high signal-to-background uptake levels [147]. Interestingly, this tracer was employed previously to detect the inflammatory component of the autoimmune disease sarcoidosis, even though it did not outperform the sugar analog [18F]FDG, which is routinely applied in PET [148].

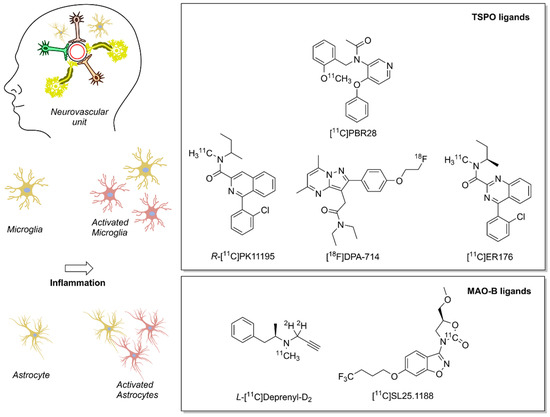

4. Imaging Redox Biomarkers of Neuroinflammation in the Clinic

Several biomarkers and associated radiotracers were proposed for the detection of different steps in the neuroinflammation biochemical cascade. We refer the interested reader to two detailed and comprehensive overviews of recent neuroinflammation PET biomarkers [149][150]. Here, we provide a brief overview of two imaging biomarkers for neuroinflammation, which are linked to the redox landscape: TSPO and MAO–B (Figure 3). Both imaging biomarkers play an important role in the cellular redox landscape, and are associated with clinically validated tracers. TSPO is involved in mitochondrial activity, whereas MAO–B generates H2O2 in the mitochondria [151][152]. As of now, PET is one of the few methods that warrants adequate sensitivity for measuring the abundance of transiently expressed redox-related biomarkers of neuroinflammation with translational potential.

Figure 3. Positron emission tomography (PET) radioligands for translational molecular imaging of two biomarkers of neuroinflammation. The 18 kDa translocator protein (TSPO) and the enzyme monoamine oxidase B (MAO–B) are overexpressed in response to inflammation predominately in microglia and astrocytes, respectively.

References

- Yuan, N.; Chen, Y.; Xia, Y.; Dai, J.; Liu, C. Inflammation-related biomarkers in major psychiatric disorders: A cross-disorder assessment of reproducibility and specificity in 43 meta-analyses. Transl. Psychiatry 2019, 9, 233.

- Radtke, F.A.; Chapman, G.; Hall, J.; Syed, Y.A. Modulating Neuroinflammation to Treat Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 5071786.

- Meyer, J.H.; Cervenka, S.; Kim, M.J.; Kreisl, W.C.; Henter, I.D.; Innis, R.B. Neuroinflammation in psychiatric disorders: PET imaging and promising new targets. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 1064–1074.

- Matthews, P.M. Chronic inflammation in multiple sclerosis—Seeing what was always there. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 15, 582–593.

- Vaughn, C.B.; Jakimovski, D.; Kavak, K.S.; Ramanathan, M.; Benedict, R.H.B.; Zivadinov, R.; Weinstock-Guttman, B. Epidemiology and treatment of multiple sclerosis in elderly populations. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 15, 329–342.

- Thompson, A.J.; Baranzini, S.E.; Geurts, J.; Hemmer, B.; Ciccarelli, O. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet 2018, 391, 1622–1636.

- Scheltens, P.; Blennow, K.; Breteler, M.M.; de Strooper, B.; Frisoni, G.B.; Salloway, S.; Van der Flier, W.M. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 2016, 388, 505–517.

- Kinney, J.W.; Bemiller, S.M.; Murtishaw, A.S.; Leisgang, A.M.; Salazar, A.M.; Lamb, B.T. Inflammation as a central mechanism in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018, 4, 575–590.

- Heneka, M.T.; Carson, M.J.; El Khoury, J.; Landreth, G.E.; Brosseron, F.; Feinstein, D.L.; Jacobs, A.H.; Wyss-Coray, T.; Vitorica, J.; Ransohoff, R.M.; et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 388–405.

- Schwab, C.; Klegeris, A.; McGeer, P.L. Inflammation in transgenic mouse models of neurodegenerative disorders. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1802, 889–902.

- Park, J.C.; Han, S.H.; Mook-Jung, I. Peripheral inflammatory biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease: A brief review. BMB Rep. 2020, 53, 10–19.

- Ng, A.; Tam, W.W.; Zhang, M.W.; Ho, C.S.; Husain, S.F.; McIntyre, R.S.; Ho, R.C. IL-1beta, IL-6, TNF- alpha and CRP in Elderly Patients with Depression or Alzheimer’s disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12050.

- Hur, J.Y.; Frost, G.R.; Wu, X.; Crump, C.; Pan, S.J.; Wong, E.; Barros, M.; Li, T.; Nie, P.; Zhai, Y.; et al. The innate immunity protein IFITM3 modulates gamma-secretase in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 2020, 586, 735–740.

- Baruch, K.; Deczkowska, A.; David, E.; Castellano, J.M.; Miller, O.; Kertser, A.; Berkutzki, T.; Barnett-Itzhaki, Z.; Bezalel, D.; Wyss-Coray, T.; et al. Aging. Aging-induced type I interferon response at the choroid plexus negatively affects brain function. Science 2014, 346, 89–93.

- Turnbull, I.R.; Gilfillan, S.; Cella, M.; Aoshi, T.; Miller, M.; Piccio, L.; Hernandez, M.; Colonna, M. Cutting edge: TREM-2 attenuates macrophage activation. J. Immunol. 2006, 177, 3520–3524.

- Zheng, H.; Liu, C.C.; Atagi, Y.; Chen, X.F.; Jia, L.; Yang, L.; He, W.; Zhang, X.; Kang, S.S.; Rosenberry, T.L.; et al. Opposing roles of the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 and triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-like transcript 2 in microglia activation. Neurobiol. Aging 2016, 42, 132–141.

- Bouchon, A.; Hernandez-Munain, C.; Cella, M.; Colonna, M. A DAP12-mediated pathway regulates expression of CC chemokine receptor 7 and maturation of human dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 2001, 194, 1111–1122.

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Zhao, Y.; Dua, P.; Rogaev, E.I.; Lukiw, W.J. microRNA-34a-Mediated Down-Regulation of the Microglial-Enriched Triggering Receptor and Phagocytosis-Sensor TREM2 in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150211.

- Shi, Y.; Holtzman, D.M. Interplay between innate immunity and Alzheimer disease: APOE and TREM2 in the spotlight. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 759–772.

- Campbell, B.C.V.; Khatri, P. Stroke. Lancet 2020, 396, 129–142.

- Sommer, C.J. Ischemic stroke: Experimental models and reality. Acta Neuropathol. 2017, 133, 245–261.

- He, Z.; Ning, N.; Zhou, Q.; Khoshnam, S.E.; Farzaneh, M. Mitochondria as a therapeutic target for ischemic stroke. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 146, 45–58.

- Jones, D.P.; Sies, H. The Redox Code. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2015, 23, 734–746.

- Sies, H.; Berndt, C.; Jones, D.P. Oxidative Stress. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017, 86, 715–748.

- Jena, N.R. DNA damage by reactive species: Mechanisms, mutation and repair. J. Biosci. 2012, 37, 503–517.

- Berlett, B.S.; Stadtman, E.R. Protein oxidation in aging, disease, and oxidative stress. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 20313–20316.

- Redza-Dutordoir, M.; Averill-Bates, D.A. Activation of apoptosis signalling pathways by reactive oxygen species. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1863, 2977–2992.

- Naik, E.; Dixit, V.M. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species drive proinflammatory cytokine production. J. Exp. Med. 2011, 208, 417–420.

- McEwen, B.S. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators: Central role of the brain. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 8, 367–381.

- Jackson, P.A.; Pialoux, V.; Corbett, D.; Drogos, L.; Erickson, K.I.; Eskes, G.A.; Poulin, M.J. Promoting brain health through exercise and diet in older adults: A physiological perspective. J. Physiol. 2016, 594, 4485–4498.

- Niewada, M.; Michel, P. Lifestyle modification for stroke prevention: Facts and fiction. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2016, 29, 9–13.

- Galimanis, A.; Mono, M.L.; Arnold, M.; Nedeltchev, K.; Mattle, H.P. Lifestyle and stroke risk: A review. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2009, 22, 60–68.

- Altobelli, E.; Angeletti, P.M.; Rapacchietta, L.; Petrocelli, R. Overview of Meta-Analyses: The Impact of Dietary Lifestyle on Stroke Risk. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3582.

- Popa-Wagner, A.; Dumitrascu, D.I.; Capitanescu, B.; Petcu, E.B.; Surugiu, R.; Fang, W.H.; Dumbrava, D.A. Dietary habits, lifestyle factors and neurodegenerative diseases. Neural Regen. Res. 2020, 15, 394–400.

- Madore, C.; Yin, Z.; Leibowitz, J.; Butovsky, O. Microglia, Lifestyle Stress, and Neurodegeneration. Immunity 2020, 52, 222–240.

- Ruiz-Nunez, B.; Pruimboom, L.; Dijck-Brouwer, D.A.; Muskiet, F.A. Lifestyle and nutritional imbalances associated with Western diseases: Causes and consequences of chronic systemic low-grade inflammation in an evolutionary context. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2013, 24, 1183–1201.

- Mintzer, J.; Donovan, K.A.; Kindy, A.Z.; Lock, S.L.; Chura, L.R.; Barracca, N. Lifestyle Choices and Brain Health. Front. Med. 2019, 6, 204.

- Dando, S.J.; Mackay-Sim, A.; Norton, R.; Currie, B.J.; St John, J.A.; Ekberg, J.A.; Batzloff, M.; Ulett, G.C.; Beacham, I.R. Pathogens penetrating the central nervous system: Infection pathways and the cellular and molecular mechanisms of invasion. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 27, 691–726.

- Simon, D.W.; McGeachy, M.J.; Bayir, H.; Clark, R.S.; Loane, D.J.; Kochanek, P.M. The far-reaching scope of neuroinflammation after traumatic brain injury. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2017, 13, 171–191.

- Suzuki, T.; Hidaka, T.; Kumagai, Y.; Yamamoto, M. Environmental pollutants and the immune response. Nat. Immunol. 2020, 21, 1486–1495.

- Sharma, R.K.; Agrawal, M. Biological effects of heavy metals: An overview. J. Environ. Biol. 2005, 26, 301–313.

- Patel, S.; Sangeeta, S. Pesticides as the drivers of neuropsychotic diseases, cancers, and teratogenicity among agro-workers as well as general public. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2019, 26, 91–100.

- Lee, G.H.; Choi, K.C. Adverse effects of pesticides on the functions of immune system. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 235, 108789.

- Gangemi, S.; Gofita, E.; Costa, C.; Teodoro, M.; Briguglio, G.; Nikitovic, D.; Tzanakakis, G.; Tsatsakis, A.M.; Wilks, M.F.; Spandidos, D.A.; et al. Occupational and environmental exposure to pesticides and cytokine pathways in chronic diseases (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2016, 38, 1012–1020.

- Li, B.; Ding, Y.; Cheng, X.; Sheng, D.; Xu, Z.; Rong, Q.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Ji, X.; Zhang, Y. Polyethylene microplastics affect the distribution of gut microbiota and inflammation development in mice. Chemosphere 2020, 244, 125492.

- Hwang, J.; Choi, D.; Han, S.; Jung, S.Y.; Choi, J.; Hong, J. Potential toxicity of polystyrene microplastic particles. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7391.

- Jayaraj, R.L.; Rodriguez, E.A.; Wang, Y.; Block, M.L. Outdoor Ambient Air Pollution and Neurodegenerative Diseases: The Neuroinflammation Hypothesis. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2017, 4, 166–179.

- Block, M.L.; Calderon-Garciduenas, L. Air pollution: Mechanisms of neuroinflammation and CNS disease. Trends Neurosci. 2009, 32, 506–516.

- Babadjouni, R.M.; Hodis, D.M.; Radwanski, R.; Durazo, R.; Patel, A.; Liu, Q.; Mack, W.J. Clinical effects of air pollution on the central nervous system; a review. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2017, 43, 16–24.

- Calderon-Garciduenas, L.; Gonzalez-Maciel, A.; Reynoso-Robles, R.; Hammond, J.; Kulesza, R.; Lachmann, I.; Torres-Jardon, R.; Mukherjee, P.S.; Maher, B.A. Quadruple abnormal protein aggregates in brainstem pathology and exogenous metal-rich magnetic nanoparticles (and engineered Ti-rich nanorods). The substantia nigrae is a very early target in young urbanites and the gastrointestinal tract a key brainstem portal. Environ. Res. 2020, 191, 110139.

- Medzhitov, R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature 2008, 454, 428–435.

- Turner, M.D.; Nedjai, B.; Hurst, T.; Pennington, D.J. Cytokines and chemokines: At the crossroads of cell signalling and inflammatory disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1843, 2563–2582.

- Kany, S.; Vollrath, J.T.; Relja, B. Cytokines in Inflammatory Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 6008.

- Forrester, S.J.; Kikuchi, D.S.; Hernandes, M.S.; Xu, Q.; Griendling, K.K. Reactive Oxygen Species in Metabolic and Inflammatory Signaling. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 877–902.

- Mittal, M.; Siddiqui, M.R.; Tran, K.; Reddy, S.P.; Malik, A.B. Reactive oxygen species in inflammation and tissue injury. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 20, 1126–1167.

- Schieber, M.; Chandel, N.S. ROS function in redox signaling and oxidative stress. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, R453–R462.

- Sies, H.; Jones, D.P. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) as pleiotropic physiological signalling agents. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 363–383.

- Dickinson, B.C.; Chang, C.J. Chemistry and biology of reactive oxygen species in signaling or stress responses. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 7, 504–511.

- Yoboue, E.D.; Sitia, R.; Simmen, T. Redox crosstalk at endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane contact sites (MCS) uses toxic waste to deliver messages. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9.

- Boveris, A.; Oshino, N.; Chance, B. The cellular production of hydrogen peroxide. Biochem. J. 1972, 128, 617–630.

- Reczek, C.R.; Chandel, N.S. ROS-dependent signal transduction. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2015, 33, 8–13.

- Narayanan, D.; Ma, S.N.; Ozcelik, D. Targeting the Redox Landscape in Cancer Therapy. Cancers 2020, 12, 1706.

- Sies, H. Oxidative stress: A concept in redox biology and medicine. Redox Biol. 2015, 4, 180–183.

- Oberkampf, M.; Guillerey, C.; Mouries, J.; Rosenbaum, P.; Fayolle, C.; Bobard, A.; Savina, A.; Ogier-Denis, E.; Enninga, J.; Amigorena, S.; et al. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species regulate the induction of CD8(+) T cells by plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2241.

- Holmdahl, R.; Sareila, O.; Pizzolla, A.; Winter, S.; Hagert, C.; Jaakkola, N.; Kelkka, T.; Olsson, L.M.; Wing, K.; Backdahl, L. Hydrogen peroxide as an immunological transmitter regulating autoreactive T cells. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 18, 1463–1474.

- Matsukawa, J.; Matsuzawa, A.; Takeda, K.; Ichijo, H. The ASK1-MAP kinase cascades in mammalian stress response. J. Biochem. 2004, 136, 261–265.

- Lee, K.; Esselman, W.J. cAMP potentiates H2O2-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation without the requirement for MEK1/2 phosphorylation. Cell Signal. 2001, 13, 645–652.

- Cargnello, M.; Roux, P.P. Activation and function of the MAPKs and their substrates, the MAPK-activated protein kinases. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2011, 75, 50–83.

- Yin, J.; Duan, J.L.; Cui, Z.J.; Ren, W.K.; Li, T.J.; Yin, Y.L. Hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress activates NF-kappa B and Nrf2/Keap1 signals and triggers autophagy in piglets. Rsc Adv. 2015, 5, 15479–15486.

- Morgan, M.J.; Liu, Z.G. Crosstalk of reactive oxygen species and NF-kappaB signaling. Cell Res. 2011, 21, 103–115.

- Christian, F.; Smith, E.L.; Carmody, R.J. The Regulation of NF-kappaB Subunits by Phosphorylation. Cells 2016, 5, 12.

- Luo, B.; Wang, J.; Liu, Z.; Shen, Z.; Shi, R.; Liu, Y.Q.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, M.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Z. Phagocyte respiratory burst activates macrophage erythropoietin signalling to promote acute inflammation resolution. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12177.

- El-Benna, J.; Hurtado-Nedelec, M.; Marzaioli, V.; Marie, J.C.; Gougerot-Pocidalo, M.A.; Dang, P.M. Priming of the neutrophil respiratory burst: Role in host defense and inflammation. Immunol. Rev. 2016, 273, 180–193.

- Schroder, K. NADPH oxidase-derived reactive oxygen species: Dosis facit venenum. Exp. Physiol. 2019, 104, 447–452.

- Singel, K.L.; Segal, B.H. NOX2-dependent regulation of inflammation. Clin. Sci. 2016, 130, 479–490.

- Light, D.R.; Walsh, C.; O’Callaghan, A.M.; Goetzl, E.J.; Tauber, A.I. Characteristics of the cofactor requirements for the superoxide-generating NADPH oxidase of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Biochemistry 1981, 20, 1468–1476.

- Decoursey, T.E.; Ligeti, E. Regulation and termination of NADPH oxidase activity. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2005, 62, 2173–2193.

- Lugrin, J.; Rosenblatt-Velin, N.; Parapanov, R.; Liaudet, L. The role of oxidative stress during inflammatory processes. Biol. Chem. 2014, 395, 203–230.

- Hunter, P. The inflammation theory of disease. The growing realization that chronic inflammation is crucial in many diseases opens new avenues for treatment. EMBO Rep. 2012, 13, 968–970.

- Zindel, J.; Kubes, P. DAMPs, PAMPs, and LAMPs in Immunity and Sterile Inflammation. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2020, 15, 493–518.

- Broz, P.; Dixit, V.M. Inflammasomes: Mechanism of assembly, regulation and signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 407–420.

- Abais, J.M.; Xia, M.; Zhang, Y.; Boini, K.M.; Li, P.L. Redox regulation of NLRP3 inflammasomes: ROS as trigger or effector? Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2015, 22, 1111–1129.

- Sanchez-Rodriguez, R.; Munari, F.; Angioni, R.; Venegas, F.; Agnellini, A.; Castro-Gil, M.P.; Castegna, A.; Luisetto, R.; Viola, A.; Canton, M. Targeting monoamine oxidase to dampen NLRP3 inflammasome activation in inflammation. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2020.

- Zhong, Z.; Zhai, Y.; Liang, S.; Mori, Y.; Han, R.; Sutterwala, F.S.; Qiao, L. TRPM2 links oxidative stress to NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1611.

- Gatliff, J.; East, D.A.; Singh, A.; Alvarez, M.S.; Frison, M.; Matic, I.; Ferraina, C.; Sampson, N.; Turkheimer, F.; Campanella, M. A role for TSPO in mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis and redox stress signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e2896.

- Horng, T. Calcium signaling and mitochondrial destabilization in the triggering of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Trends Immunol. 2014, 35, 253–261.

- Bergsbaken, T.; Fink, S.L.; Cookson, B.T. Pyroptosis: Host cell death and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 99–109.

- Zheng, D.; Liwinski, T.; Elinav, E. Inflammasome activation and regulation: Toward a better understanding of complex mechanisms. Cell Discov. 2020, 6, 36.

- Orning, P.; Lien, E.; Fitzgerald, K.A. Gasdermins and their role in immunity and inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 2019, 216, 2453–2465.

- Broz, P.; Pelegrin, P.; Shao, F. The gasdermins, a protein family executing cell death and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 143–157.

- Swanson, K.V.; Deng, M.; Ting, J.P. The NLRP3 inflammasome: Molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 477–489.

- Dinarello, C.A.; Simon, A.; van der Meer, J.W. Treating inflammation by blocking interleukin-1 in a broad spectrum of diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2012, 11, 633–652.

- Schwaid, A.G.; Spencer, K.B. Strategies for Targeting the NLRP3 Inflammasome in the Clinical and Preclinical Space. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 101–122.

- Mangan, M.S.J.; Olhava, E.J.; Roush, W.R.; Seidel, H.M.; Glick, G.D.; Latz, E. Targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome in inflammatory diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 588–606.

- Marin, I.A.; Kipnis, J. Central Nervous System: (Immunological) Ivory Tower or Not? Neuropsychopharmacology 2017, 42, 28–35.

- Galea, I.; Bechmann, I.; Perry, V.H. What is immune privilege (not)? Trends Immunol. 2007, 28, 12–18.

- Hartenstein, V.; Giangrande, A. Connecting the nervous and the immune systems in evolution. Commun. Biol. 2018, 1, 64.

- Bennett, M.L.; Bennett, F.C. The influence of environment and origin on brain resident macrophages and implications for therapy. Nat. Neurosci. 2020, 23, 157–166.

- Lannes, N.; Eppler, E.; Etemad, S.; Yotovski, P.; Filgueira, L. Microglia at center stage: A comprehensive review about the versatile and unique residential macrophages of the central nervous system. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 114393–114413.

- Kaushal, V.; Dye, R.; Pakavathkumar, P.; Foveau, B.; Flores, J.; Hyman, B.; Ghetti, B.; Koller, B.H.; LeBlanc, A.C. Neuronal NLRP1 inflammasome activation of Caspase-1 coordinately regulates inflammatory interleukin-1-beta production and axonal degeneration-associated Caspase-6 activation. Cell Death Differ. 2015, 22, 1676–1686.

- Freeman, L.; Guo, H.; David, C.N.; Brickey, W.J.; Jha, S.; Ting, J.P. NLR members NLRC4 and NLRP3 mediate sterile inflammasome activation in microglia and astrocytes. J. Exp. Med. 2017, 214, 1351–1370.

- Kawana, N.; Yamamoto, Y.; Ishida, T.; Saito, Y.; Konno, H.; Arima, K.; Satoh, J.-I. Reactive astrocytes and perivascular macrophages express NLRP3 inflammasome in active demyelinating lesions of multiple sclerosis and necrotic lesions of neuromyelitis optica and cerebral infarction. Clin. Exp. Neuroimmunol. 2013, 4, 296–304.

- McKenzie, B.A.; Mamik, M.K.; Saito, L.B.; Boghozian, R.; Monaco, M.C.; Major, E.O.; Lu, J.Q.; Branton, W.G.; Power, C. Caspase-1 inhibition prevents glial inflammasome activation and pyroptosis in models of multiple sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E6065–E6074.

- Gong, Z.; Pan, J.; Shen, Q.; Li, M.; Peng, Y. Mitochondrial dysfunction induces NLRP3 inflammasome activation during cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury. J. Neuroinflamm. 2018, 15, 242.

- Welser-Alves, J.V.; Milner, R. Microglia are the major source of TNF-alpha and TGF-beta1 in postnatal glial cultures; regulation by cytokines, lipopolysaccharide, and vitronectin. Neurochem. Int. 2013, 63, 47–53.

- West, P.K.; Viengkhou, B.; Campbell, I.L.; Hofer, M.J. Microglia responses to interleukin-6 and type I interferons in neuroinflammatory disease. Glia 2019, 67, 1821–1841.

- Herzog, C.; Pons Garcia, L.; Keatinge, M.; Greenald, D.; Moritz, C.; Peri, F.; Herrgen, L. Rapid clearance of cellular debris by microglia limits secondary neuronal cell death after brain injury in vivo. Development 2019, 146.

- Claude, J.; Linnartz-Gerlach, B.; Kudin, A.P.; Kunz, W.S.; Neumann, H. Microglial CD33-related Siglec-E inhibits neurotoxicity by preventing the phagocytosis-associated oxidative burst. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 18270–18276.

- Simpson, D.S.A.; Oliver, P.L. ROS Generation in Microglia: Understanding Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Neurodegenerative Disease. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 743.

- Elenkov, I.J.; Iezzoni, D.G.; Daly, A.; Harris, A.G.; Chrousos, G.P. Cytokine dysregulation, inflammation and well-being. Neuroimmunomodulation 2005, 12, 255–269.

- Chen, L.; Deng, H.; Cui, H.; Fang, J.; Zuo, Z.; Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L. Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 7204–7218.

- Varatharaj, A.; Galea, I. The blood-brain barrier in systemic inflammation. Brain Behav. Immun. 2017, 60, 1–12.

- Profaci, C.P.; Munji, R.N.; Pulido, R.S.; Daneman, R. The blood-brain barrier in health and disease: Important unanswered questions. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217.

- Fogal, B.; Hewett, S.J. Interleukin-1beta: A bridge between inflammation and excitotoxicity? J. Neurochem. 2008, 106, 1–23.

- Floyd, R.A.; Hensley, K.; Jaffery, F.; Maidt, L.; Robinson, K.; Pye, Q.; Stewart, C. Increased oxidative stress brought on by pro-inflammatory cytokines in neurodegenerative processes and the protective role of nitrone-based free radical traps. Life Sci. 1999, 65, 1893–1899.

- Thornton, P.; Pinteaux, E.; Gibson, R.M.; Allan, S.M.; Rothwell, N.J. Interleukin-1-induced neurotoxicity is mediated by glia and requires caspase activation and free radical release. J. Neurochem. 2006, 98, 258–266.

- Campbell, I.L.; Abraham, C.R.; Masliah, E.; Kemper, P.; Inglis, J.D.; Oldstone, M.B.; Mucke, L. Neurologic disease induced in transgenic mice by cerebral overexpression of interleukin 6. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 10061–10065.

- Fattori, E.; Lazzaro, D.; Musiani, P.; Modesti, A.; Alonzi, T.; Ciliberto, G. IL-6 expression in neurons of transgenic mice causes reactive astrocytosis and increase in ramified microglial cells but no neuronal damage. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1995, 7, 2441–2449.

- Eugster, H.P.; Frei, K.; Kopf, M.; Lassmann, H.; Fontana, A. IL-6-deficient mice resist myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-induced autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Eur. J. Immunol. 1998, 28, 2178–2187.

- Beattie, E.C.; Stellwagen, D.; Morishita, W.; Bresnahan, J.C.; Ha, B.K.; Von Zastrow, M.; Beattie, M.S.; Malenka, R.C. Control of synaptic strength by glial TNFalpha. Science 2002, 295, 2282–2285.

- Zou, J.Y.; Crews, F.T. TNF alpha potentiates glutamate neurotoxicity by inhibiting glutamate uptake in organotypic brain slice cultures: Neuroprotection by NF kappa B inhibition. Brain Res. 2005, 1034, 11–24.

- Schwarzlander, M.; Dick, T.P.; Meyer, A.J.; Morgan, B. Dissecting Redox Biology Using Fluorescent Protein Sensors. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2016, 24, 680–712.

- Jiang, X.; Wang, L.; Carroll, S.L.; Chen, J.; Wang, M.C.; Wang, J. Challenges and Opportunities for Small-Molecule Fluorescent Probes in Redox Biology Applications. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2018, 29, 518–540.

- Ikawa, M.; Okazawa, H.; Nakamoto, Y.; Yoneda, M. PET Imaging for Oxidative Stress in Neurodegenerative Disorders Associated with Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 861.

- Sugiura, K.; Mihara, S.; Fu, N.; Hisabori, T. Real-time monitoring of the in vivo redox state transition using the ratiometric redox state sensor protein FROG/B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 16019–16026.

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zou, Y.; Yang, Y. Visualization of Nicotine Adenine Dinucleotide Redox Homeostasis with Genetically Encoded Fluorescent Sensors. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2018, 28, 213–229.

- Hatori, Y.; Kubo, T.; Sato, Y.; Inouye, S.; Akagi, R.; Seyama, T. Visualization of the Redox Status of Cytosolic Glutathione Using the Organelle- and Cytoskeleton-Targeted Redox Sensors. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 129.

- Kostyuk, A.I.; Panova, A.S.; Kokova, A.D.; Kotova, D.A.; Maltsev, D.I.; Podgorny, O.V.; Belousov, V.V.; Bilan, D.S. In Vivo Imaging with Genetically Encoded Redox Biosensors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8164.

- Formella, I.; Svahn, A.J.; Radford, R.A.W.; Don, E.K.; Cole, N.J.; Hogan, A.; Lee, A.; Chung, R.S.; Morsch, M. Real-time visualization of oxidative stress-mediated neurodegeneration of individual spinal motor neurons in vivo. Redox Biol. 2018, 19, 226–234.

- Leslie, K.G.; Kolanowski, J.L.; Trinh, N.; Carrara, S.; Anscomb, M.D.; Yang, K.; Hogan, C.F.; Jolliffe, K.A.; New, E.J. Nicotinamide-Appended Fluorophores as Fluorescent Redox Sensors. Aust. J. Chem. 2020, 73, 895–902.

- Ni, Y.; Liu, H.; Dai, D.; Mu, X.; Xu, J.; Shao, S. Chromogenic, Fluorescent, and Redox Sensors for Multichannel Imaging and Detection of Hydrogen Peroxide in Living Cell Systems. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 10152–10158.

- Balke, J.; Volz, P.; Neumann, F.; Brodwolf, R.; Wolf, A.; Pischon, H.; Radbruch, M.; Mundhenk, L.; Gruber, A.D.; Ma, N.; et al. Visualizing Oxidative Cellular Stress Induced by Nanoparticles in the Subcytotoxic Range Using Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging. Small 2018, 14, e1800310.

- Baltsavias, S.; Van Treuren, W.; Weber, M.J.; Charthad, J.; Baker, S.; Sonnenburg, J.L.; Arbabian, A. In Vivo Wireless Sensors for Gut Microbiome Redox Monitoring. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 67, 1821–1830.

- Massoud, T.F.; Gambhir, S.S. Molecular imaging in living subjects: Seeing fundamental biological processes in a new light. Genes Dev. 2003, 17, 545–580.

- Willmann, J.K.; van Bruggen, N.; Dinkelborg, L.M.; Gambhir, S.S. Molecular imaging in drug development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 591–607.

- Piel, M.; Vernaleken, I.; Rosch, F. Positron emission tomography in CNS drug discovery and drug monitoring. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 9232–9258.

- Chu, W.; Chepetan, A.; Zhou, D.; Shoghi, K.I.; Xu, J.; Dugan, L.L.; Gropler, R.J.; Mintun, M.A.; Mach, R.H. Development of a PET radiotracer for non-invasive imaging of the reactive oxygen species, superoxide, in vivo. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 12, 4421–4431.

- Hou, C.; Hsieh, C.J.; Li, S.; Lee, H.; Graham, T.J.; Xu, K.; Weng, C.C.; Doot, R.K.; Chu, W.; Chakraborty, S.K.; et al. Development of a Positron Emission Tomography Radiotracer for Imaging Elevated Levels of Superoxide in Neuroinflammation. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018, 9, 578–586.

- Wilson, A.A.; Sadovski, O.; Nobrega, J.N.; Raymond, R.J.; Bambico, F.R.; Nashed, M.G.; Garcia, A.; Bloomfield, P.M.; Houle, S.; Mizrahi, R.; et al. Evaluation of a novel radiotracer for positron emission tomography imaging of reactive oxygen species in the central nervous system. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2017, 53, 14–20.

- Egami, H.; Nakagawa, S.; Katsura, Y.; Kanazawa, M.; Nishiyama, S.; Sakai, T.; Arano, Y.; Tsukada, H.; Inoue, O.; Todoroki, K.; et al. (18)F-Labeled dihydromethidine: Positron emission tomography radiotracer for imaging of reactive oxygen species in intact brain. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020, 18, 2387–2391.

- Carroll, V.N.; Truillet, C.; Shen, B.; Flavell, R.R.; Shao, X.; Evans, M.J.; VanBrocklin, H.F.; Scott, P.J.; Chin, F.T.; Wilson, D.M. [(11)C]Ascorbic and [(11)C]dehydroascorbic acid, an endogenous redox pair for sensing reactive oxygen species using positron emission tomography. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 4888–4890.

- Carroll, V.; Michel, B.W.; Blecha, J.; Van Brocklin, H.; Keshari, K.; Wilson, D.; Chang, C.J. A boronate-caged [(1)(8)F]FLT probe for hydrogen peroxide detection using positron emission tomography. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 14742–14745.

- Fujibayashi, Y.; Taniuchi, H.; Yonekura, Y.; Ohtani, H.; Konishi, J.; Yokoyama, A. Copper-62-ATSM: A new hypoxia imaging agent with high membrane permeability and low redox potential. J. Nucl. Med. 1997, 38, 1155–1160.

- Gangemi, V.; Mignogna, C.; Guzzi, G.; Lavano, A.; Bongarzone, S.; Cascini, G.L.; Sabatini, U. Impact of [(64)Cu][Cu(ATSM)] PET/CT in the evaluation of hypoxia in a patient with Glioblastoma: A case report. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 1197.

- Lewerenz, J.; Hewett, S.J.; Huang, Y.; Lambros, M.; Gout, P.W.; Kalivas, P.W.; Massie, A.; Smolders, I.; Methner, A.; Pergande, M.; et al. The cystine/glutamate antiporter system x(c)(-) in health and disease: From molecular mechanisms to novel therapeutic opportunities. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 18, 522–555.

- Koglin, N.; Mueller, A.; Berndt, M.; Schmitt-Willich, H.; Toschi, L.; Stephens, A.W.; Gekeler, V.; Friebe, M.; Dinkelborg, L.M. Specific PET imaging of xC- transporter activity using a (1)(8)F-labeled glutamate derivative reveals a dominant pathway in tumor metabolism. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 6000–6011.

- Park, S.Y.; Na, S.J.; Kumar, M.; Mosci, C.; Wardak, M.; Koglin, N.; Bullich, S.; Mueller, A.; Berndt, M.; Stephens, A.W.; et al. Clinical Evaluation of (4S)-4-(3-[(18)F]Fluoropropyl)-L-glutamate ((18)F-FSPG) for PET/CT Imaging in Patients with Newly Diagnosed and Recurrent Prostate Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 5380–5387.

- Chae, S.Y.; Choi, C.M.; Shim, T.S.; Park, Y.; Park, C.S.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, S.J.; Oh, S.J.; Kim, S.Y.; Baek, S.; et al. Exploratory Clinical Investigation of (4S)-4-(3-18F-Fluoropropyl)-L-Glutamate PET of Inflammatory and Infectious Lesions. J. Nucl. Med. 2016, 57, 67–69.

- Kreisl, W.C.; Kim, M.-J.; Coughlin, J.M.; Henter, I.D.; Owen, D.R.; Innis, R.B. PET imaging of neuroinflammation in neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 940–950.

- Jain, P.; Chaney, A.M.; Carlson, M.L.; Jackson, I.M.; Rao, A.; James, M.L. Neuroinflammation PET Imaging: Current Opinion and Future Directions. J. Nucl. Med. 2020, 61, 1107–1112.

- Betlazar, C.; Middleton, R.J.; Banati, R.; Liu, G.-J. The Translocator Protein (TSPO) in Mitochondrial Bioenergetics and Immune Processes. Cells 2020, 9, 512.

- Zorov, D.B.; Juhaszova, M.; Sollott, S.J. Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and ROS-Induced ROS Release. Physiol. Rev. 2014, 94, 909–950.