| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Isabel González-Gascón y Marín | + 1253 word(s) | 1253 | 2021-04-15 08:49:17 | | | |

| 2 | Dean Liu | -31 word(s) | 1222 | 2021-04-27 02:42:04 | | |

Video Upload Options

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is an extremely heterogeneous disease. With the advent of oral targeted agents (Tas) the treatment of CLL has undergone a revolution, which has been accompanied by an improvement in patient’s survival and quality of life.

1. Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most frequent chronic leukemia in Western countries. The diagnosis is usually incidental in a routine blood test and its outcome is extremely heterogeneous. Some patients present with a rapidly progressive evolution, while others remain at an indolent state for the rest of their lives. Antitumor therapy is only required if active disease is documented, according to the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (iwCLL) criteria [1]. Furthermore, response to treatment is also variable and may be predicted by different biomarkers. This is of vital importance at this time, in which treatment algorithms have drastically changed and chemoimmunotherapy (CIT) has been replaced by targeted agents (Tas) for most patients [2][3]. Research is moving ahead at a staggering speed and, consequently, the therapeutic arsenal is growing. Oral targeted treatments approved and available worldwide are: ibrutinib, the first generation of Bruton Tirosine Kinase inhibitors (BTKi); idelalisib, the first generation of phosphatidyl-inositol 3-kinase inhibitors (PI3Ki); and venetoclax (BCL-2 inhibitor). The European Medicine Agency (EMA) has just approved acalabrutinib, a second class BTKi. The second class PI3Ki, duvelisib is also available in some countries. Other second class BTKi (zanubrutinib), PI3Ki (umbralisib) or new reversible, non-covalent BTKi (pirtobrutinib, ARQ 531) are under investigation and will hopefully be available soon [4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18]. Therefore, the identification of prognostic and predictive biomarkers is relevant, not only for patient counseling but also for planning follow-up or selecting treatment at a time where a shift towards personalized medicine is taking place.

The difference between the terms prognostic and predictive biomarker has been previously addressed in depth [19][20]. In brief, prognostic biomarkers separate groups of patients with different outcomes regardless of treatment. On the contrary, a predictive biomarker provides information about the possible benefit of a specific treatment and can be used in the clinical decision-making process [21]. Many of the most powerful prognostic and predictive biomarkers were identified in the CIT era [22][23][24][25][26][27][28] but the validity of most of them has been evaluated also with oral Tas [6][11][12][29][30][31].

Although individual factors can be a very important prognostic tool, reality is more complex, as each patient may harbor several biomarkers with different prognostic value. To overcome this issue, prognostic scores have been developed integrating biomarkers into models. The Rai and Binet systems, proposed almost half a century ago, were the pioneers and, despite their limitations, they are still in force today [32][33]. Since then, various prognostic models and nomograms were proposed that can be applied at different moments during the course of the disease. The most established today is the CLL-International Prognostic Index (CLL-IPI), which has demonstrated its ability to predict overall survival (OS), time to first therapy (TTFT) and progression-free survival (PFS) in the CIT setting [34][35]. It has also shown to predict TTFT in early-stage CLL [36] and community-based cohorts of patients [37][38]. However, its utility to predict PFS and even OS in patients treated with Tas is limited [39]. Thus, other models have recently emerged to evaluate prognosis in this setting [40][41].

2. Prognostic Biomarkers: All That Glitters Is Not Gold

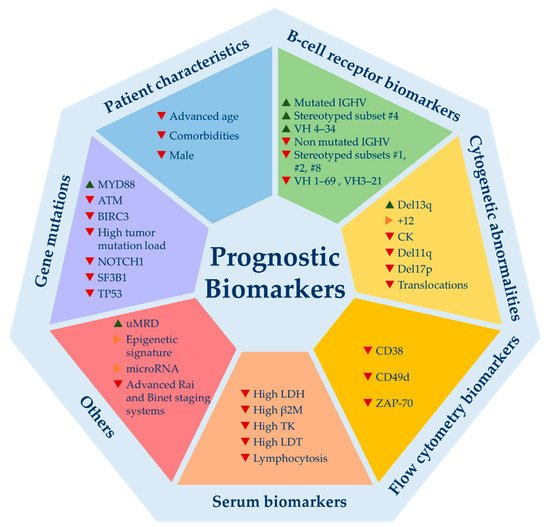

Over the last 50 years, plenty of biomarkers with ability to predict CLL evolution were identified. The most relevant, classified by categories, are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Relevant prognostic biomarkers for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Del13q = 13q deletion; +12 = trisomy 12; CK = complex karyotype; del11q = 11q deletion; del17p = 17p deletion; LDH = lactate dehydrogenase levels; β2M = beta-2-microglobulin levels; TK = thymidine kinase; LDT = lymphocyte doubling time; uMRD = undetectable minimal residual disease. ▲ indicates good prognosis; ▶ indicates good and bad prognosis or intermediate prognosis; ▼ indicates poor prognosis.

Even though they emerged in the era of CIT, most are valid today, since they are capable to predict time to first treatment (TTFT), which is not influenced by the choice of therapy [22][23][24][25][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65]. The mutational status of immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region (IGHV) gene, cytogenetic abnormalities detected by FISH, CD49d expression and TP53 mutations are the biomarkers that have been consolidated as the most powerful ones and are supported by the best scientific evidence [50][66]. Others such as ZAP-70 and CD-38 have lost their strength, although their prognostic value is unquestionable. These flow cytometry biomarkers may be useful if IGHV mutation status is not available, as they act as surrogate markers. Among B-cell receptor biomarkers, a selective usage of IGHV genes in CLL has been described, with an overuse of certain genes. Some of these gene usages have been associated with clinical outcome such as VH1-69, VH3-21 (bad outcome) or VH 4-34 (good outcome) [67][68][69][70]. In addition, almost a third of CLL patients express stereotyped B cell receptor immunoglobulins (BcR IG). Some of these subsets also harbor prognostic value highlighting subsets #1, #2, #8 (bad prognosis) and #4 (good prognosis) [63][71]. Recently, a single point mutation in IGLV3-21 (R110-mutated IGLV3-21) has been studied, identifying an aggressive biological subtype of CLL [72].

Recurrent gene mutations identified by next generation whole exome or whole genome sequencing carry important prognostic information [61][73][74]. However, its implementation in routine practice has not been fully recommended to date, with the exception of TP53 mutation [1]. A great variety of mutations have been identified, but only a few occur in more than ~5% of the patients. Among them stand out NOTCH1, SF3B1, ATM, BIRC3, POT1 and MYD88. All but MYD88 have been associated with adverse outcome and other poor prognostic biomarkers [75]. Some patient-related and tumor-load variables such as age, comorbidities, beta-2-microglobulin levels (B2M), lymphocytosis or lymphocyte doubling time (LDT) are available in virtually all patients and remain valid in predicting TTFT [76][77]. Novel markers such as complex karyotype (CK), stereotyped subsets, micro-RNAs or epigenetic subsets need more evidence to be used in the routine setting. Finally, minimal residual disease (MRD) is one of the strongest predictors of PFS and OS in CLL patients treated with CIT [78]. Indeed, undetectable MRD (uMRD) is considered a surrogate marker for PFS in the context of clinical trials. Regarding targeted treatments, BTKi or PI3Ki obtain very long PFS despite their low rates of complete responses (CR) and uMRD. Therefore, uMRD is not a valid prognostic biomarker for patients treated with BTK or PI3K inhibitors [5][6][11][12][13]. Conversely, venetoclax-based regimens induce high rates of uMRD enabling a fixed-duration treatment which has established uMRD as a therapeutic goal for these combinations. Moreover, the prognostic value of achieving uMRD with venetoclax has been demonstrated, not only in the relapsed/refractory (R/R) setting but also as a frontline treatment (Murano and CLL14 phase 3 trials) [10][31]. Combos of novel agents (TA) between them +/− anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies or, less frequently, with CIT is what immediate future holds. Preliminary results of trials using these combinations are impressive with the highest rates of uMRD ever seen (>50–70%), which might turn uMRD as the most powerful biomarker to predict prognosis in CLL patients that require treatment [79][80][81][82][83]. In fact, it could be used to guide treatment decisions in the near future by helping to decide when to stop or intensify therapy. Nevertheless, questions such as how to proceed with MRD results after a fixed duration schedule (stop, continue or change treatment) remain open. In summary, despite this large amount of biomarkers, not all have been externally and prospectively validated and, furthermore, few are valuable for clinical decision-making.

References

- Hallek, M.; Cheson, B.D.; Catovsky, D.; Caligaris-Cappio, F.; Dighiero, G.; Döhner, H.; Hillmen, P.; Keating, M.; Montserrat, E.; Chiorazzi, N.; et al. iwCLL guidelines for diagnosis, indications for treatment, response assessment, and supportive management of CLL. Blood 2018, 131, 2745–2760.

- Eichhorst, B.; Robak, T.; Montserrat, E.; Ghia, P.; Niemann, C.U.; Kater, A.P.; Gregor, M.; Cymbalista, F.; Buske, C.; Hillmen, P.; et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 23–33.

- NCCN. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia/Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma Version 2.2021. Available online: (accessed on 9 February 2021).

- Byrd, J.C.; Furman, R.R.; Coutre, S.E.; Flinn, I.W.; Burger, J.A.; Blum, K.; Sharman, J.P.; Wierda, W.; Zhao, W.; Heerema, N.A.; et al. Ibrutinib Treatment for First-Line and Relapsed/Refractory Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Final Analysis of the Pivotal Phase Ib/II PCYC-1102 Study. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 3918–3927.

- Burger, J.A.; Barr, P.M.; Robak, T.; Owen, C.; Ghia, P.; Tedeschi, A.; Bairey, O.; Hillmen, P.; Coutre, S.E.; Devereux, S.; et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of first-line ibrutinib treatment for patients with CLL/SLL: 5 years of follow-up from the phase 3 RESONATE-2 study. Leukemia 2020, 34, 787–798.

- Munir, T.; Brown, J.R.; O’Brien, S.; Barrientos, J.C.; Barr, P.M.; Reddy, N.M.; Coutre, S.; Tam, C.S.; Mulligan, S.P.; Jaeger, U.; et al. Final analysis from RESONATE: Up to six years of follow-up on ibrutinib in patients with previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia or small lymphocytic lymphoma. Am. J. Hematol. 2019, 94, 1353–1363.

- Woyach, J.A.; Ruppert, A.S.; Heerema, N.A.; Zhao, W.; Booth, A.M.; Ding, W.; Bartlett, N.L.; Brander, D.M.; Barr, P.M.; Rogers, K.A.; et al. Ibrutinib Regimens versus Chemoimmunotherapy in Older Patients with Untreated CLL. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2517–2528.

- Shanafelt, T.D.; Wang, X.V.; Kay, N.E.; Hanson, C.A.; O’Brien, S.; Barrientos, J.; Jelinek, D.F.; Braggio, E.; Leis, J.F.; Zhang, C.C.; et al. Ibrutinib-Rituximab or Chemoimmunotherapy for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 432–443.

- Kater, A.P.; Seymour, J.F.; Hillmen, P.; Eichhorst, B.; Langerak, A.W.; Owen, C.; Verdugo, M.; Wu, J.; Punnoose, E.A.; Jiang, Y.; et al. Fixed Duration of Venetoclax-Rituximab in Relapsed/Refractory Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Eradicates Minimal Residual Disease and Prolongs Survival: Post-Treatment Follow-Up of the MURANO Phase III Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 269–277.

- Al-Sawaf, O.; Zhang, C.; Tandon, M.; Sinha, A.; Fink, A.-M.; Robrecht, S.; Samoylova, O.; Liberati, A.M.; Pinilla-Ibarz, J.; Opat, S.; et al. Venetoclax plus obinutuzumab versus chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab for previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL14): Follow-up results from a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 1188–1200.

- Ghia, P.; Pluta, A.; Wach, M.; Lysak, D.; Kozak, T.; Simkovic, M.; Kaplan, P.; Kraychok, I.; Illes, A.; de la Serna, J.; et al. ASCEND: Phase III, Randomized Trial of Acalabrutinib Versus Idelalisib Plus Rituximab or Bendamustine Plus Rituximab in Relapsed or Refractory Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 2849–2861.

- Sharman, J.P.; Egyed, M.; Jurczak, W.; Skarbnik, A.; Pagel, J.M.; Flinn, I.W.; Kamdar, M.; Munir, T.; Walewska, R.; Corbett, G.; et al. Calabrutinib with or without obinutuzumab versus chlorambucil and obinutuzumab for treatment-naive chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (ELEVATE-TN): A randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2020, 395, 1278–1291.

- Sharman, J.P.; Coutre, S.E.; Furman, R.R.; Cheson, B.D.; Pagel, J.M.; Hillmen, P.; Barrientos, J.C.; Zelenetz, A.D.; Kipps, T.J.; Flinn, I.W.; et al. Final results of a randomized, phase iii study of rituximab with or without idelalisib followed by open-label idelalisib in patients with relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 1391–1402.

- Flinn, I.W.; Hillmen, P.; Montillo, M.; Nagy, Z.; Illés, Á.; Etienne, G.; Delgado, J.; Kuss, B.J.; Tam, C.S.; Gasztonyi, Z.; et al. The phase 3 DUO trial: Duvelisib vs ofatumumab in relapsed and refractory CLL/SLL. Blood 2018, 132, 2446–2455.

- Tam, C.S.; Trotman, J.; Opat, S.; Burger, J.A.; Cull, G.; Gottlieb, D.; Harrup, R.; Johnston, P.B.; Marlton, P.; Munoz, J.; et al. Phase 1 study of the selective BTK inhibitor zanubrutinib in B-cell malignancies and safety and efficacy evaluation in CLL. Blood 2019, 134, 851–859.

- Danilov, A.V.; Herbaux, C.; Walter, H.S.; Hillmen, P.; Rule, S.A.; Kio, E.A.; Karlin, L.; Dyer, M.J.S.; Mitra, S.S.; Yi, P.C.; et al. Phase Ib Study of Tirabrutinib in Combination with Idelalisib or Entospletinib in Previously Treated Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 2810–2818.

- Mato, A.R.; Ghosh, N.; Schuster, S.J.; Lamanna, N.; Pagel, J.M.; Flinn, I.W.; Barrientos, J.; Rai, K.R.; Reeves, J.A.; Cheson, B.D.; et al. Phase 2 Study of the Safety and Efficacy of Umbralisib in Patients with CLL Who are Intolerant to BTK or PI3Kδ Inhibitor Therapy. Blood 2020.

- Iskierka-Jażdżewska, E.; Robak, T. Investigational treatments for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: A focus on phase 1 and 2 clinical trials. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2020, 1–14.

- Rossi, D.; Gerber, B.; Stüssi, G. Predictive and prognostic biomarkers in the era of new targeted therapies for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk. Lymphoma 2017, 58, 1548–1560.

- Montserrat, E.; Gale, R.P. Predicting the outcome of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Progress and uncertainty. Cancer 2019, 125, 3699–3705.

- Califf, R.M. Biomarker definitions and their applications. Exp. Biol. Med. 2018, 243, 213–221.

- Döhner, H.; Stilgenbauer, S.; Benner, A.; Leupolt, E.; Kröber, A.; Bullinger, L.; Döhner, K.; Bentz, M.; Lichter, P. Genomic Aberrations and Survival in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 343, 1910–1916.

- Damle, R.N.; Wasil, T.; Fais, F.; Ghiotto, F.; Valetto, A.; Allen, S.L.; Buchbinder, A.; Budman, D.; Dittmar, K.; Kolitz, J.; et al. Ig V Gene Mutation Status and CD38 Expression as Novel Prognostic Indicators in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Blood 1999, 94, 1840–1847.

- Hamblin, T.J.; Davis, Z.; Gardiner, A.; Oscier, D.G.; Stevenson, F.K. Unmutated Ig V(H) genes are associated with a more aggressive form of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 1999, 94, 1848–1854.

- Crespo, M.; Bosch, F.; Villamor, N.; Bellosillo, B.; Colomer, D.; Rozman, M.; Marcé, S.; López-Guillermo, A.; Campo, E.; Montserrat, E. ZAP-70 Expression as a Surrogate for Immunoglobulin-Variable-Region Mutations in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 1764–1775.

- Baumann, T.; Delgado, J.; Santacruz, R.; Martínez-Trillos, A.; Rozman, M.; Aymerich, M.; López, C.; Costa, D.; Carrió, A.; Villamor, N.; et al. CD49d (ITGA4) expression is a predictor of time to first treatment in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and mutatedIGHVstatus. Br. J. Haematol. 2016, 172, 48–55.

- Ghia, P.; Guida, G.; Stella, S.; Gottardi, D.; Geuna, M.; Strola, G.; Scielzo, C.; Caligaris-Cappio, F. The pattern of CD38 expression defines a distinct subset of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients at risk of disease progression. Blood 2003, 101, 1262–1269.

- Herling, C.D.; Klaumünzer, M.; Rocha, C.K.; Altmüller, J.; Thiele, H.; Bahlo, J.; Kluth, S.; Crispatzu, G.; Herling, M.; Schiller, J.; et al. Complex karyotypes and KRAS and POT1 mutations impact outcome in CLL after chlorambucil-based chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy. Blood 2016, 128, 395–404.

- Brown, J.R.; Hillmen, P.; O’Brien, S.; Barrientos, J.C.; Reddy, N.M.; Coutre, S.E.; Tam, C.S.; Mulligan, S.P.; Jaeger, U.; Barr, P.M.; et al. Extended follow-up and impact of high-risk prognostic factors from the phase 3 RESONATE study in patients with previously treated CLL/SLL. Leukemia 2018, 32, 83–91.

- Tausch, E.; Schneider, C.; Robrecht, S.; Zhang, C.; Dolnik, A.; Bloehdorn, J.; Bahlo, J.; Al-Sawaf, O.; Ritgen, M.; Fink, A.-M.; et al. Prognostic and predictive impact of genetic markers in patients with CLL treated with obinutuzumab and venetoclax. Blood 2020.

- Kater, A.P.; Wu, J.Q.; Kipps, T.; Eichhorst, B.; Hillmen, P.; D’Rozario, J.; Assouline, S.; Owen, C.; Robak, T.; de la Serna, J.; et al. Venetoclax Plus Rituximab in Relapsed Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: 4-Year Results and Evaluation of Impact of Genomic Complexity and Gene Mutations from the MURANO Phase III Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 4042–4054.

- Binet, J.L.; Auquier, A.; Dighiero, G.; Chastang, C.; Piguet, H.; Goasguen, J.; Vaugier, G.; Potron, G.; Colona, P.; Oberling, F.; et al. A new prognostic classification of chronic lymphocytic leukemia derived from a multivariate survival analysis. Cancer 1981, 48, 198–206.

- Rai, K.R.; Sawitsky, A.; Cronkite, E.P.; Chanana, A.D.; Levy, R.N.; Pasternack, B.S. Clinical staging of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 1975, 46, 219–234.

- International CLL-IPI Working Group. An international prognostic index for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL-IPI): A meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 779–790.

- Gentile, M.; Shanafelt, T.D.; Mauro, F.R.; Reda, G.; Rossi, D.; Laurenti, L.; Del Principe, M.I.; Cutrona, G.; Angeletti, I.; Coscia, M.; et al. Predictive value of the CLL-IPI in CLL patients receiving chemo-immunotherapy as first-line treatment. Eur. J. Haematol. 2018.

- Molica, S.; Shanafelt, T.D.; Giannarelli, D.; Gentile, M.; Mirabelli, R.; Cutrona, G.; Levato, L.; Di Renzo, N.; Di Raimondo, F.; Musolino, C.; et al. The chronic lymphocytic leukemia international prognostic index predicts time to first treatment in early CLL: Independent validation in a prospective cohort of early stage patients. Am. J. Hematol. 2016, 91, 1090–1095.

- Da Cunha-Bang, C.; Christiansen, I.; Niemann, C.U. The CLL-IPI applied in a population-based cohort. Blood 2016, 128, 2181–2183.

- Muñoz-Novas, C.; Poza-Santaella, M.; Marín, I.G.-G.Y., I; Hernández-Sánchez, M.; Rodríguez-Vicente, A.-E.; Infante, M.-S.; Heras, C.; Foncillas, M.-Á.; Marín, K.; Hernández-Rivas, J.-M.; et al. The International Prognostic Index for Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia has the Higher Value in Predicting Overall Outcome Compared with the Barcelona-Brno Biomarkers Only Prognostic Model and the MD Anderson Cancer Center Prognostic Index. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 9506979.

- Molica, S.; Giannarelli, D.; Mirabelli, R.; Levato, L.; Shanafelt, T.D. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia international prognostic index (CLL-IPI) in patients receiving chemoimmuno or targeted therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Hematol. 2018, 97, 2005–2008.

- Soumerai, J.D.; Ni, A.; Darif, M.; Londhe, A.; Xing, G.; Mun, Y.; Kay, N.E.; Shanafelt, T.D.; Rabe, K.G.; Byrd, J.C.; et al. Prognostic risk score for patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia treated with targeted therapies or chemoimmunotherapy: A retrospective, pooled cohort study with external validations. Lancet Haematol. 2019, 6, e366–e374.

- Ahn, I.E.; Tian, X.; Ipe, D.; Cheng, M.; Albitar, M.; Tsao, L.C.; Zhang, L.; Ma, W.; Herman, S.E.M.; Gaglione, E.M.; et al. Prediction of Outcome in Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Treated with Ibrutinib: Development and Validation of a Four-Factor Prognostic Model. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, JCO2000979.

- Van Dyke, D.L.; Werner, L.; Rassenti, L.Z.; Neuberg, D.; Ghia, E.; Heerema, N.A.; Dal Cin, P.; Dell Aquila, M.; Sreekantaiah, C.; Greaves, A.W.; et al. The Dohner fluorescence in situ hybridization prognostic classification of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL): The CLL Research Consortium experience. Br. J. Haematol. 2016, 173, 105–113.

- Autore, F.; Strati, P.; Innocenti, I.; Corrente, F.; Trentin, L.; Cortelezzi, A.; Visco, C.; Coscia, M.; Cuneo, A.; Gozzetti, A.; et al. Elevated Lactate Dehydrogenase has Prognostic Relevance in Treatment-Naïve Patients Affected by Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia with Trisomy 12. Cancers 2019, 11, 896.

- Delgado, J.; Pratt, G.; Phillips, N.; Briones, J.; Fegan, C.; Nomdedeu, J.; Pepper, C.; Aventin, A.; Ayats, R.; Brunet, S.; et al. Beta2-microglobulin is a better predictor of treatment-free survival in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia if adjusted according to glomerular filtration rate. Br. J. Haematol. 2009, 145, 801–805.

- Hallek, M.; Langenmayer, I.; Nerl, C.; Knauf, W.; Dietzfelbinger, H.; Adorf, D.; Ostwald, M.; Busch, R.; Kuhn-Hallek, I.; Thiel, E.; et al. Elevated serum thymidine kinase levels identify a subgroup at high risk of disease progression in early, nonsmoldering chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 1999, 93, 1732–1737.

- Montserrat, E.; Sanchez-Bisono, J.; Viñolas, N.; Rozman, C. Lymphocyte doubling time in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: Analysis of its prognostic significance. Br. J. Haematol. 1986, 62, 567–575.

- Tadmor, T.; Braester, A.; Najib, D.; Aviv, A.; Herishanu, Y.; Yuklea, M.; Shvidel, L.; Rahimi-Levene, N.; Ruchlemer, R.; Arad, A.; et al. A new risk model to predict time to first treatment in chronic lymphocytic leukemia based on heavy chain immunoparesis and summated free light chain. Eur. J. Haematol. 2019, 103, 335–341.

- Catovsky, D.; Fooks, J.; Richards, S. Prognostic factors in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: The importance of age, sex and response to treatment in survival. Br. J. Haematol. 1989, 72, 141–149.

- Strugov, V.; Stadnik, E.; Virts, Y.; Andreeva, T.; Zaritskey, A. Impact of age and comorbidities on the efficacy of FC and FCR regimens in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Ann. Hematol. 2018, 97, 2153–2161.

- Bulian, P.; Shanafelt, T.D.; Fegan, C.; Zucchetto, A.; Cro, L.; Nückel, H.; Baldini, L.; Kurtova, A.V.; Ferrajoli, A.; Burger, J.A.; et al. CD49d is the Strongest Flow Cytometry-Based Predictor of Overall Survival in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 897–904.

- Ibrahem, L.; Elderiny, W.E.; Elhelw, L.; Ismail, M. CD49d and CD26 are independent prognostic markers for disease progression in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 2015, 55, 154–160.

- Hernández, J.A.; Rodríguez, A.E.; González, M.; Benito, R.; Fontanillo, C.; Sandoval, V.; Romero, M.; Martín-Núñez, G.; de Coca, A.G.; Fisac, R.; et al. A high number of losses in 13q14 chromosome band is associated with a worse outcome and biological differences in patients with B-cell chronic lymphoid leukemia. Haematologica 2009, 94, 364–371.

- Cavazzini, F.; Hernandez, J.A.; Gozzetti, A.; Rossi, A.R.; de Angeli, C.; Tiseo, R.; Bardi, A.; Tammiso, E.; Crupi, R.; Lenoci, M.P.; et al. Chromosome 14q32 translocations involving the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia identify a disease subset with poor prognosis. Br. J. Haematol. 2008, 142, 529–537.

- Hernández, J.Á.; Hernández-Sánchez, M.; Rodríguez-Vicente, A.E.; Grossmann, V.; Collado, R.; Heras, C.; Puiggros, A.; Martín, A.Á.; Puig, N.; Benito, R.; et al. A Low Frequency of Losses in 11q Chromosome is Associated with Better Outcome and Lower Rate of Genomic Mutations in Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143073.

- Marín, I.G.-G.Y.; Hernández-Sánchez, M.; Rodríguez-Vicente, A.-E.; Sanzo, C.; Aventín, A.; Puiggros, A.; Collado, R.; Heras, C.; Muñoz, C.; Delgado, J.; et al. A high proportion of cells carrying trisomy 12 is associated with a worse outcome in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Hematol. Oncol. 2016, 34, 84–92.

- Delgado, J.; Espinet, B.; Oliveira, A.C.; Abrisqueta, P.; de la Serna, J.; Collado, R.; Loscertales, J.; Lopez, M.; Hernandez-Rivas, J.A.; Ferra, C.; et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia with 17p deletion: A retrospective analysis of prognostic factors and therapy results. Br. J. Haematol. 2012, 157, 67–74.

- Heerema, N.A.; Muthusamy, N.; Zhao, Q.; Ruppert, A.S.; Breidenbach, H.; Andritsos, L.A.; Grever, M.R.; Maddocks, K.J.; Woyach, J.; Awan, F.; et al. Prognostic significance of translocations in the presence of mutated IGHV and of cytogenetic complexity at diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Haematologica 2020.

- Pérez-Carretero, C.; Hernández-Sánchez, M.; González, T.; Quijada-Álamo, M.; Martín-Izquierdo, M.; Hernández-Sánchez, J.-M.; Vidal, M.-J.; de Coca, A.G.; Aguilar, C.; Vargas-Pabón, M.; et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients with IGH translocations are characterized by a distinct genetic landscape with prognostic implications. Int. J. Cancer 2020, 147, 2780–2792.

- Baliakas, P.; Hadzidimitriou, A.; Sutton, L.-A.; Minga, E.; Agathangelidis, A.; Nichelatti, M.; Tsanousa, A.; Scarfò, L.; Davis, Z.; Yan, X.-J.; et al. Clinical effect of stereotyped B-cell receptor immunoglobulins in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: A retrospective multicentre study. Lancet Haematol. 2014, 1, e74–e84.

- Marín, I.G.-G.Y., I; Hernández, J.A.; Martín, A.; Alcoceba, M.; Sarasquete, M.E.; Rodríguez-Vicente, A.; Heras, C.; de Las Heras, N.; Fisac, R.; García de Coca, A.; et al. Mutation Status and Immunoglobulin Gene Rearrangements in Patients from Northwest and Central Region of Spain with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 257517.

- Landau, D.A.; Tausch, E.; Taylor-Weiner, A.N.; Stewart, C.; Reiter, J.G.; Bahlo, J.; Kluth, S.; Bozic, I.; Lawrence, M.; Böttcher, S.; et al. Mutations driving CLL and their evolution in progression and relapse. Nature 2015, 526, 525–530.

- Puente, X.S.; Pinyol, M.; Quesada, V.; Conde, L.; Ordóñez, G.R.; Villamor, N.; Escaramis, G.; Jares, P.; Beà, S.; González-Díaz, M.; et al. Whole-genome sequencing identifies recurrent mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nature 2011, 475, 101–105.

- Jaramillo, S.; Agathangelidis, A.; Schneider, C.; Bahlo, J.; Robrecht, S.; Tausch, E.; Bloehdorn, J.; Hoechstetter, M.; Fischer, K.; Eichhorst, B.; et al. Prognostic impact of prevalent chronic lymphocytic leukemia stereotyped subsets: Analysis within prospective clinical trials of the German CLL Study Group (GCLLSG). Haematologica 2020, 105, 2598–2607.

- Queirós, A.C.; Villamor, N.; Clot, G.; Martinez-Trillos, A.; Kulis, M.; Navarro, A.; Penas, E.M.M.; Jayne, S.; Majid, A.; Richter, J.; et al. A B-cell epigenetic signature defines three biologic subgroups of chronic lymphocytic. Leukemia 2015, 29, 598–605.

- Baliakas, P.; Puiggros, A.; Xochelli, A.; Sutton, L.-A.; Nguyen-Khac, F.; Gardiner, A.; Plevova, K.; Minga, E.; Hadzidimitriou, A.; Walewska, R.; et al. Additional trisomies amongst patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia carrying trisomy 12: The accompanying chromosome makes a difference. Haematologica 2016, 101, e299–e302.

- Parikh, S.A.; Strati, P.; Tsang, M.; West, C.P.; Shanafelt, T.D. Should IGHV status and FISH testing be performed in all CLL patients at diagnosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood 2016, 127, 1752–1760.

- Thorsélius, M.; Kröber, A.; Murray, F.; Thunberg, U.; Tobin, G.; Bühler, A.; Kienle, D.; Albesiano, E.; Maffei, R.; Dao-Ung, L.-P.; et al. Strikingly homologous immunoglobulin gene rearrangements and poor outcome in VH3-21-using chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients independent of geographic origin and mutational status. Blood 2006, 107, 2889–2894.

- Ghia, P.; Stamatopoulos, K.; Belessi, C.; Moreno, C.; Stella, S.; Guida, G.; Michel, A.; Crespo, M.; Laoutaris, N.; Montserrat, E.; et al. Geographic patterns and pathogenetic implications of IGHV gene usage in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: The lesson of the IGHV3-21 gene. Blood 2005, 105, 1678–1685.

- Tobin, G.; Rosén, A.; Rosenquist, R. What is the current evidence for antigen involvement in the development of chronic lymphocytic leukemia? Hematol. Oncol. 2006, 24, 7–13.

- Xochelli, A.; Baliakas, P.; Kavakiotis, I.; Agathangelidis, A.; Sutton, L.-A.; Minga, E.; Ntoufa, S.; Tausch, E.; Yan, X.-J.; Shanafelt, T.; et al. Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia with Mutated IGHV4-34 Receptors: Shared and Distinct Immunogenetic Features and Clinical Outcomes. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 5292–5301.

- Agathangelidis, A.; Darzentas, N.; Hadzidimitriou, A.; Brochet, X.; Murray, F.; Yan, X.-J.; Davis, Z.; van Gastel-Mol, E.J.; Tresoldi, C.; Chu, C.C.; et al. Stereotyped B-cell receptors in one-third of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: A molecular classification with implications for targeted therapies. Blood 2012, 119, 4467–4475.

- Nadeu, F.; Royo, R.; Clot, G.; Duran-Ferrer, M.; Navarro, A.; Martin, S.; Lu, J.; Zenz, T.; Baumann, T.S.; Jares, P.; et al. IGLV3-21R110 identifies an aggressive biological subtype of chronic lymphocytic leukemia with intermediate epigenetics. Blood 2020.

- Puente, X.S.; Beà, S.; Valdés-Mas, R.; Villamor, N.; Gutiérrez-Abril, J.; Martín-Subero, J.I.; Munar, M.; Rubio-Pérez, C.; Jares, P.; Aymerich, M.; et al. Non-coding recurrent mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nature 2015, 526, 519–524.

- Landau, D.A.; Carter, S.L.; Stojanov, P.; McKenna, A.; Stevenson, K.; Lawrence, M.S.; Sougnez, C.; Stewart, C.; Sivachenko, A.; Wang, L.; et al. Evolution and Impact of Subclonal Mutations in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Cell 2013, 152, 714–726.

- Bosch, F.; Dalla-Favera, R. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: From genetics to treatment. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 16, 684–701.

- Yun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X. Recent progress of prognostic biomarkers and risk scoring systems in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Biomark. Res. 2020, 8, 40.

- Rigolin, G.M.; Cavallari, M.; Quaglia, F.M.; Formigaro, L.; Lista, E.; Urso, A.; Guardalben, E.; Liberatore, C.; Faraci, D.; Saccenti, E.; et al. In CLL, comorbidities and the complex karyotype are associated with an inferior outcome independently of CLL-IPI. Blood 2017, 129, 3495–3498.

- Kovacs, G.; Robrecht, S.; Fink, A.M.; Bahlo, J.; Cramer, P.; von Tresckow, J.; Maurer, C.; Langerbeins, P.; Fingerle-Rowson, G.; Ritgen, M.; et al. Minimal Residual Disease Assessment Improves Prediction of Outcome in Patients With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) Who Achieve Partial Response: Comprehensive Analysis of Two Phase III Studies of the German CLL Study Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 3758–3765.

- Tam, C.S.; Siddiqi, T.; Allan, J.N.; Kipps, T.J.; Flinn, I.W.; Kuss, B.J.; Opat, S.; Barr, P.M.; Tedeschi, A.; Jacobs, R.; et al. Ibrutinib (Ibr) Plus Venetoclax (Ven) for First-Line Treatment of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL)/Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma (SLL): Results from the MRD Cohort of the Phase 2 CAPTIVATE Study. Blood 2019, 134, 35.

- Jain, N.; Keating, M.; Thompson, P.; Ferrajoli, A.; Burger, J.; Borthakur, G.; Takahashi, K.; Estrov, Z.; Fowler, N.; Kadia, T.; et al. Ibrutinib and Venetoclax for First-Line Treatment of CLL. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 2095–2103.

- Lampson, B.L.; Tyekucheva, S.; Crombie, J.L.; Kim, A.I.; Merryman, R.W.; Lowney, J.; Montegaard, J.; Patterson, V.; Jacobson, C.A.; Jacobsen, E.D.; et al. Preliminary Safety and Efficacy Results from a Phase 2 Study of Acalabrutinib, Venetoclax and Obinutuzumab in Patients with Previously Untreated Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL). Blood 2019, 134, 32.

- Munir, T.; Webster, N.; Boucher, R.; Dalal, S.; Brock, K.; Yates, F.J.; Sankhalpara, C.; MacDonald, D.; Fegan, C.; McCaig, A.; et al. Continued Long Term Responses to Ibrutinib + Venetoclax Treatment for Relapsed/Refractory CLL in the Blood Cancer UK TAP Clarity Trial. Blood 2020, 136, 17–18.

- Wierda, W.G.; Tam, C.; Allan, J.N.; Siddiqi, T.; Kipps, T.; Opat, S.; Tedeschi, A.; Badoux, X.C.; Kuss, B.J.; Jackson, B.; et al. Ibrutinib (Ibr) Plus Venetoclax (Ven) for First-Line Treatment of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL)/Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma (SLL): 1-Year Disease-Free Survival (DFS) Results from the MRD Cohort of the Phase 2 CAPTIVATE Study. Blood 2020, 136, 16–17.