| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ludmila Zylinska | + 1390 word(s) | 1390 | 2021-04-14 10:27:07 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | Meta information modification | 1390 | 2021-04-26 11:46:16 | | |

Video Upload Options

Ca2+-ATPases are key components of Ca2+ extrusion machinery and thus are pivotal for preservation of neuronal function.

1. Introduction

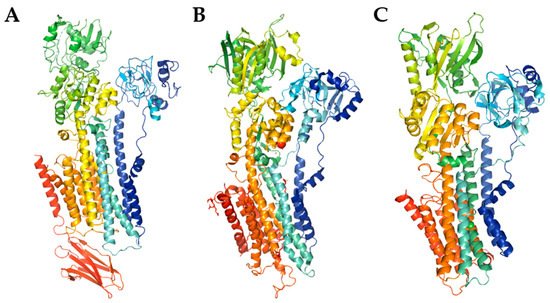

Ca2+-ATPases are key components of Ca2+ extrusion machinery and thus are pivotal for preservation of neuronal function. Among three main calcium pumps, the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA) and sarco/endoplasmic Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) are known for decades while the secretory pathway Ca2+-ATPase has been discovered in 2000s by two independent laboratories that described novel mutations leading to Hailey-Hailey disease [1][2][3]. All pumps have high affinity for Ca2+ and function to restore cytosolic Ca2+ concentration [Ca2+]c to the resting, nanomolar level following neuronal stimulations. They belong to the superfamily of mammalian P-type ATPases and are characterized by formation of a phosphorylated enzyme intermediate during catalytic cycle [1]. However, they have a low (~15%) degree of sequency identity [1], and differ in several other key features including tissue distribution, regulatory mechanisms, and contribution to neuronal Ca2+ homeostasis. Each pump is encoded by multiple genes giving rise to a number of isoforms and further splice variants, which often possess distinguishable kinetic parameters and are dedicated to unique and highly regulated neural processes [4]. Naturally, the pumps share essential basic properties such as membrane topology, catalytic mechanism and probably the general features of 3D structure [5][6], although the structure of SPCA pump has not been solved yet (Figure 1). The rapid expansion of the knowledge on pumps peculiar role, which run parallel to the advances in neuronal Ca2+ signaling, led to the identification of several diseases associated either directly or indirectly with Ca2+ pumps malfunction. Most of these defects have genetic background and the number of studies have been aimed to characterize their severity, effect on neuronal Ca2+ homeostasis and signaling as well as neuronal survival. Besides known neuropathologies, defects in Ca2+ pumps and alterations in the mechanisms regulating their activity may also produce subtle, tissue-specific disturbances that are not clinically manifested, yet they may affect neuronal machinery controlling and processing Ca2+ signal.

Figure 1. The model of PMCA ((A), PDB entry code 6A69) and SERCA ((B), PDB entry code 3W5C) structures, and SPCA structure prediction using SWISS-MODEL (C). The cartoon models were generated with PyMOL.

2. Calmodulin—Ubiquitous Ca2+ Sensor in Neurons

Most commonly, detection and transduction of Ca2+ signals in neurons are orchestrated by ubiquitous messenger called calmodulin. CaM is known as a relatively small (149aa; 16.7 kDa) and highly conserved calcium-binding sensor synthesized in all eukaryotic cells. It is particularity involved in synaptic signaling processes, neurotransmitter release and neuroplasticity by modulation (called “calmodulation”) of a large array of binding partners such as enzymes (e.g., adenylate cyclase, calcineurin, cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase, nitric oxide synthase, and certain kinases), transcription factors (e.g., CREB, NeuroD2, NFAT and MEF2) as well as various ion channels and transporters [7][8][9][10].

In human, CaM is encoded by three independent genes CALM1, CALM2, CALM3 located on chromosomes 14q32.11; 2p21; and 19q13.32, respectively, which are collectively transcribed into at least eight mRNAs using different alternative polyadenylation signals (reviewed in [7][11]). Next, the resulting protein is susceptible to undergo various post-translational modifications, mainly phosphorylation on tyrosine (Thr26, Thr29, Thr44, Thr79, Tyr99, Thr117, and Tyr138) and serine (Ser81, and Ser101) sites [12]; acetylation of the N-terminal alanine [13]; trimethylation of the Lys115 [14]; and proteolytic cleavage at the C-terminal domain [15], all collectively regulating CaM biological activity. The crystal structure of mature CaM contains two independently folded lobes (N-lobe and C-lobe) connected by a flexible central α-helical linker, that differ by calcium affinity and kinetics of calcium dissociation. Each of these globular clusters can bind up to two free Ca2+ ions via a pair of helix-loop-helix motives (EF-hands) in a cooperative manner (Kd = 5 · 10−7 M to 5 · 10−6 M) [16][17][18]. Because of subtle structural differences between these lobes resulting from evolutionary processes [19], EF hands in the C-lobe exhibit a three- to five times higher affinity for Ca2+. However, they possess slower rate of ion binding than the regions of EF hands located in the N-lobe, establishing the broad range of CaM sensitivity to the changes in calcium concentrations in the intracellular space [20]. CaM is susceptible to dramatic structural rearrangements via partially exposed hydrophobic patch on the C-terminal domain which may interact with CaM-binding proteins (CaMBPs) in a Ca2+ -free (apo-CaM) state or in partially calcium-saturated forms (two Ca2+ ions bound to the C-terminus) [16]. Up to date, over three hundred different calmodulin targets with specific binding sites and unique affinities for CaM, many of which located in the central nervous system (CNS) neurons [21], have been validated and extensively characterized [22]. The analysis of over 80 CaM complexes compiled in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) has revealed that CaM binding sites not always contain defined consensus sequence but rather share some common biochemical and biophysical properties such as high helix-forming propensities, positively charged binding region and the presence of hydrophobic anchor residues [8][22]. Thus, the classification of several CaM-binding motifs is determined by the spacing between these anchor residues as was extensively discussed by Mruk and colleagues [23]. As observed from sequence analysis of several CaMBPs, their IQ motif ([FILV]Qxxx[RK]Gxxx[RK]xx[FILVWY]) with highly conserved amino acid residues at positions 1, 2, 5, 6, 11, and 14 or IQ-like ([FILV]Qxxx[RK]Gxxxxxxxx) motif may also bind CaM in the presence or absence of Ca2+ [23][24].

Considering the diversity of CaM interactions and its abundance in the brain (up to 100 μM range) [25], it seems rational to suspect that disruption of these multifunctional interactions regulating Ca2+-dependent intracellular signal transduction cascades may be implicated in the development of numerous neuropsychiatric disorders. Moreover, there is increasing evidence suggesting that pathophysiology of these states is intimately related to the disturbed neuronal calcium homeostasis also mediated by ATP-driven pumps located in the plasma membrane, in the membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), or Golgi compartments.

3. Plasma Membrane Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA)—The Only Calcium Pump Directly Regulated by Calmodulin

PMCA is one of the most important and sensitive players in maintaining of low resting Ca2+ concentration, and ensuring a fast recovery of [Ca2+]c to the basal level following neuronal excitation [26]. The enzyme was first described by Schatzmann in 1960s as ATP-powered mechanism that removes calcium from red blood cells [27], whereas further studies revealed the presence of PMCA in other cells, including neurons [28][29][30] Structurally, PMCA comprises of ten transmembrane segments with N- and C- terminal tails both located on the cytosolic site [31]. Most of the regulatory regions including acidic phospholipids, protein kinase C (PKC), protein kinase A (PKA) and the crucial natural activator—CaM, are located at the C- terminus. The important regulatory role of CaM in stimulating of PMCA is associated with increasing the affinity of the pump for calcium and the maximum rate of calcium extrusion. In the activation process, CaM removes the auto-inhibitory C-terminal domain from the active site and releases the enzyme from auto-inhibition [32]. It is also worth mentioning that PMCA is so far the only known calcium pump directly activated by CaM [26].

In mammals, four isoforms of PMCA (PMCA1-PMCA4), structurally similar to each other, have been found [4] but their expression depends on cell type (Table 1). The PMCA1 and PMCA4 are widely expressed in virtually all animal tissues and both play a house-keeping role.

Table 1. Properties of PMCA isoforms. Modified based on [1].

| PMCA1 | PMCA2 | PMCA3 | PMCA4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue Distribution | Ubiquitous | Restricted (brain) |

Restricted (brain) |

Ubiquitous |

| Developmental Expression/Switch | Isoform switch fetal/adult | Isoform switch fetal/adult | Isoform switch fetal/adult | Isoform switch fetal/adult |

| Affinity CaM (Kd nM) | 40–50 | 2–4 | 8 | 3–40 |

Expression of PMCA2 and PMCA3 is highly restricted to excitable cells and their high concentration has been detected in the CNS [4]. PMCA2 is especially abundant in cerebellar Purkinje cells and granule cells, but it also localizes to the cerebral cortex and hippocampus [33]. PMCA3, in turn, is present predominantly in cerebellar granule cells and in the choroid plexus [34] what suggests its role in generation and release of cerebrospinal fluid. Additionally, PMCA isoforms are characterized by distinct calmodulin sensitivity (Table 1) and specific kinetic properties. PMCA2 and PMCA3 are referred to as “fast” isoforms due to their high basal activity and high affinity for CaM, whereas PMCA1 and PMCA4 are much slower despite their strong stimulation by CaM [1]. It has been suggested that the cell response to a physiological stimulus depends on significant differences in the kinetic parameters of the individual isoforms. In the brain, distribution of PMCA isoforms clearly alters during development, what may indicate their specific role in embryogenesis and further in postnatal period [35].

References

- Brini, M.; Carafoli, E. Calcium Pumps in Health and Disease. Physiol. Rev. 2009, 89, 1341–1378.

- Hu, Z.; Bonifas, J.M.; Beech, J.; Bench, G.; Shigihara, T.; Ogawa, H.; Ikeda, S.; Mauro, T.M.; Epstein, E.H., Jr. Mutations in ATP2C1, encoding a calcium pump, cause Hailey-Hailey disease. Nat. Genet. 2000, 24, 61–65.

- Sudbrak, R.; Brown, J.M.; Dobson-Stone, C.; Carter, S.A.; Ramser, J.; White, J.; Healy, E.; Dissanayake, M.; Larrègue, M.; Perrussel, M.; et al. Hailey-Hailey disease is caused by mutations in ATP2C1 encoding a novel Ca2+ pump. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000, 9, 1131–1140.

- Strehler, E.E.; Zacharias, D.A. Role of Alternative Splicing in Generating Isoform Diversity Among Plasma Membrane Calcium Pumps. Physiol. Rev. 2001, 81, 21–50.

- Gong, D.; Chi, X.; Ren, K.; Huang, G.; Zhou, G.; Yan, N.; Lei, J.; Zhou, Q. Structure of the human plasma membrane Ca. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3623.

- Toyoshima, C.; Iwasawa, S.; Ogawa, H.; Hirata, A.; Tsueda, J.; Inesi, G. Crystal structures of the calcium pump and sarcolipin in the Mg2+-bound E1 state. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 495, 260–264.

- Friedberg, F.; Rhoads, A.R.; Friedberg, A.R. Evolutionary Aspects of Calmodulin. IUBMB Life 2001, 51, 215–221.

- Hoeflich, K.P.; Ikura, M. Calmodulin in action: Diversity in target recognition and activation mechanisms. Cell 2002, 108, 739–742.

- Vetter, S.W.; Leclerc, E. Novel aspects of calmodulin target recognition and activation. JBIC J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 270, 404–414.

- Jiang, X.; Lautermilch, N.J.; Watari, H.; Westenbroek, R.E.; Scheuer, T.; Catterall, W.A. Modulation of CaV2.1 channels by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II bound to the C-terminal domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 105, 341–346.

- Kortvely, E.; Gulya, K. Calmodulin, and various ways to regulate its activity. Life Sci. 2004, 74, 1065–1070.

- Villalobo, A. The multifunctional role of phospho-calmodulin in pathophysiological processes. Biochem. J. 2018, 475, 4011–4023.

- Cobb, J.A.; Roberts, D.M. Structural Requirements for N-Trimethylation of Lysine 115 of Calmodulin. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 18969–18975.

- Hofmann, N.R. Calmodulin methylation: Another layer of regulation in calcium signaling. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 4284.

- Thulin, E.; Andersson, A.; Drakenberg, T.; Forsén, S.; Vogel, H.J. Metal ion and drug binding to proteolytic fragments of calmodulin: Proteolytic cadmium-113 and proton nuclear magnetic resonance studies. Biochem. J. 1984, 23, 1862–1870.

- Chin, D.; Means, A.R. Calmodulin: A prototypical calcium sensor. Trends Cell Biol. 2000, 10, 322–328.

- Grabarek, Z. Structural Basis for Diversity of the EF-hand Calcium-binding Proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 359, 509–525.

- Gifford, J.L.; Walsh, M.P.; Vogel, H.J. Structures and metal-ion-binding properties of the Ca2+-binding helix–loop–helix EF-hand motifs. Biochem. J. 2007, 405, 199–221.

- Kawasaki, H.; Soma, N.; Kretsinger, R.H. Molecular Dynamics Study of the Changes in Conformation of Calmodulin with Calcium Binding and/or Target Recognition. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10688.

- Jensen, H.H.; Brohus, M.; Nyegaard, M.; Overgaard, M.T. Human Calmodulin Mutations. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018, 11, 396.

- Burgoyne, R.D. Neuronal calcium sensor proteins: Generating diversity in neuronal Ca2+ signalling. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007, 8, 182–193.

- Tidow, H.; Nissen, P. Structural diversity of calmodulin binding to its target sites. FEBS J. 2013, 280, 5551–5565.

- Mruk, K.; Farley, B.M.; Ritacco, A.W.; Kobertz, W.R. Calmodulation meta-analysis: Predicting calmodulin binding via canonical motif clustering. J. Gen. Physiol. 2014, 144, 105–114.

- Bähler, M.; Rhoads, A. Calmodulin signaling via the IQ motif. FEBS Lett. 2001, 513, 107–113.

- Biber, A.; Schmid, G.; Hempel, K. Calmodulin content in specific brain areas. Exp. Brain Res. 1984, 56, 323–326.

- Calì, T.; Brini, M.; Carafoli, E. Regulation of Cell Calcium and Role of Plasma Membrane Calcium ATPases. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2017, 332, 259–296.

- Schatzmann, H.J. ATP-dependent Ca+-Extrusion from human red cells. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 1966, 22, 364–365.

- Boczek, T.; Radzik, T.; Ferenc, B.; Zylinska, L. The Puzzling Role of Neuron-Specific PMCA Isoforms in the Aging Process. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 6338.

- Guerini, D.; García-Martin, E.; Gerber, A.; Volbracht, C.; Leist, M.; Merino, C.G.; Carafoli, E. The Expression of Plasma Membrane Ca2+ Pump Isoforms in Cerebellar Granule Neurons Is Modulated by Ca2+. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 1667–1676.

- Padányi, R.; Pászty, K.; Hegedűs, L.; Varga, K.; Papp, B.; Penniston, J.T.; Enyedi, Á. Multifaceted plasma membrane Ca2+ pumps: From structure to intracellular Ca2+ handling and cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Bioenerg. 2016, 1863, 1351–1363.

- Monteith, G.R.; Wanigasekara, Y.; Roufogalis, B.D. The plasma membrane calcium pump, its role and regulation: New complexities and possibilities. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 1998, 40, 183–190.

- Falchetto, R.; Vorherr, T.; Brunner, J.; Carafoli, E. The plasma membrane Ca2+ pump contains a site that interacts with its calmodulin-binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 2930–2936.

- Burette, A.; Rockwood, J.M.; Strehler, E.E.; Weinberg, R.J. Isoform-specific distribution of the plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase in the rat brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 2003, 467, 464–476.

- Eakin, T.J.; Antonelli, M.C.; Malchiodi, E.L.; Baskin, D.G.; Stahl, W.L. Localization of the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase isoform PMCA3 in rat cerebellum, choroid plexus and hippocampus. Mol. Brain Res. 1995, 29, 71–80.

- Zacharias, D.; Kappen, C. Developmental expression of the four plasma membrane calcium ATPase (Pmca) genes in the mouse. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Gen. Subj. 1999, 1428, 397–405.