| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Catia Giovannini | + 1801 word(s) | 1801 | 2021-04-07 10:54:36 | | | |

| 2 | Lily Guo | Meta information modification | 1801 | 2021-04-22 08:16:29 | | |

Video Upload Options

The Notch family includes evolutionary conserved genes that encode for single-pass transmembrane receptors involved in stem cell maintenance, development and cell fate determination of many cell lineages. Upon activation by different ligands, and depending on the cell type, Notch signaling plays pleomorphic roles in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) affecting neoplastic growth, invasion capability and stem like properties. A specific knowledge of the deregulated expression of each Notch receptor and ligand, coupled with resultant phenotypic changes, is still lacking in HCC. Therefore, while interfering with Notch signaling might represent a promising therapeutic approach, the complexity of Notch/ligands interactions and the variable consequences of their modulations raises concerns when performed in undefined molecular background. The gamma-secretase inhibitors (GSIs), representing the most utilized approach for Notch inhibition in clinical trials, are characterized by important adverse effects due to the non-specific nature of GSIs themselves and to the lack of molecular criteria guiding patient selection.

1. Introduction

Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) accounts for 80–90% of liver cancers and represents the third leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide. Over the past two decades, the incidence of HCC has doubled in many countries including Europe and United States [1]. While approximately 75% of HCCs were associated with hepatitis B or C infection, other major risk factors including aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) exposure, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), chronic alcohol consumption and obesity are now gaining more and more relevance [2]. Among treatment options, surgical resection and percutaneous ablation are considered “curative” modalities; however, they can be performed in a restricted fraction of patients, particularly those detected at early stages. When diagnosed at, or progressed to, intermediate-stage, the standard of care is transarterial chemoembolization [3], while large tumors or HCC with vascular invasion can be considered for radioembolization with selective internal radiation treatment (SIRT). When diagnosed at advanced stages or in the presence of extra-hepatic spread, only systemic treatments can be administered. Sorafenib, the first oral multikinase inhibitor (MKI) entering the treatment of HCC, has been the standard of care for almost ten years [4]. It inhibits angiogenesis and cell proliferation by targeting platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGF-R), vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR-2/3), c-Kit, Flt3 and Raf kinases involved in the MAPK/ERK pathway [5].The second tyrosine kinase inhibitor to be approved for the first line treatment of advanced HCC is lenvatinib, based on its non-inferiority to sorafenib [6]. In the setting of second line treatments, regorafenib and cabozantinib were approved for patients with HCC progression and ramucirumab for patients previously treated with sorafenib, with a serum AFP (Alpha-Fetoprotein) level ≥400 ng/mL [7]. Beside these molecularly-targeted agents, immuno-oncology has opened the way to a novel class of drugs modulating the expression of Immune Check Point Inhibitors (ICPI), whose aberrant expression results in the immune escape of cancer cells [8]. Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD1), Programmed Death-Ligand 1 (PDL1), Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte-Associated Protein 4 (CTLA4) are the most targeted ICPI in HCC proving to be more effective than Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (TKI), especially in combination regimens [9]. The most interesting results have been obtained so far with the association of Atezolizumab and Bevacizumab [10], however other promising combinations are under clinical investigation. Large clinical trials are however still needed for validation of these effects and for the identification of biomarkers helping the allocation of patients to the most effective treatment option in a personalized perspective. In addition, beside the fraction of patients who are non-responders to ICPIs, others may experience adverse events which prevent the prosecution of treatment. Unfortunately, the molecular classification of HCC has not entered clinical practice so far; thus, genetic and epigenetic factors driving response or resistance to each treatment are still poorly understood.Deregulation of multiple molecular signaling pathways such as Wnt/β-catenin, Ras mitogen-activated protein kinase (Ras/Raf/MAPK), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), Janus kinase (Jak)-signal transducer activator of transcription factor (Stat) (JAK/STAT) and the Hippo signaling pathway are essential for HCC development and progression [11]. Understanding the critical genes and signaling molecules in different HCC subgroups will help to develop tailored therapeutic strategies. Inhibition of a single signaling cascade may induce feedback activation of other pathways; hence, combination of different molecularly targeted agents is expected to show synergistic activity. Notch signaling modulates the development and functions of several immune cell lineages. Among these, Notch1 and Dll4 interaction participates in T cells’ lineage commitment, while Notch2-Dll1 interaction contributes to the development of marginal zone B cells [12]. In the peripheral T and B cell compartment, Notch signaling activates T cells’ proliferation and cytokine production, which, in line, are down-regulated by GSI-mediated inhibition of Notch. Similarly, Notch1 and Notch2 activation promotes naive CD8+ T cells to cytotoxic T lymphocytes, which, in turn, drive the antitumoral response and are the targets of ICPIs.Investigations on Notch signaling in T cells functions might lead to a more effective avenue for combined intervention in cancer treatment.The aim of this review is to discuss recent advances in molecular mechanisms involved in Notch signaling regulation that could represent new challenges for HCC therapy. Studies described in this review might contribute to the identification of key molecules responsible for Notch pathway regulation that could represent new therapeutic targets.

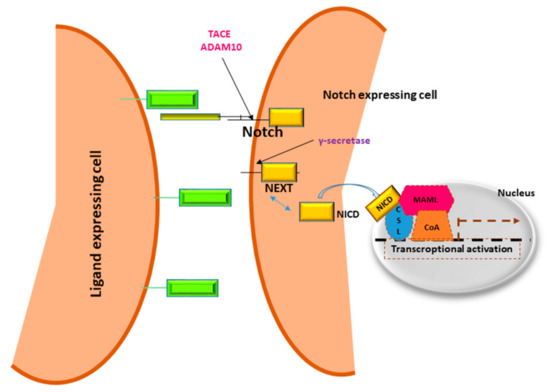

2. Notch Genes

In 1911, Morgan and colleagues described a Drosophila with a notch on a wing margin caused by a heterozygous deletion of a gene located on the X chromosome that was consequently named “NOTCH” [13]. Many years later an initial description of Notch structure and functions was provided by Wharton and colleagues and it was shown to be a conserved intracellular pathway involved in a variety of cellular processes [14]. Despite the simplicity of its activation, a fine regulation of Notch signaling is required to avoid pathological effects including cancer development. Four Notch receptors (Notch1, Notch2, Notch3, Notch4) have been identified in humans. These receptors transduce signals by interacting with transmembrane ligands of the Delta-like (DLL1, 3 and 4) and Jagged (Jagged1 and 2) protein family on neighboring cells [15]. Once processed in the Endoplasmic Reticulum and in the Golgi, Notch receptors migrate to the cell membrane where they are activated by ligand interaction [16][17]. Upon ligand binding, the Notch receptor is cleaved by the protease ADAM10 or by TACE. The resulting fragment, called Notch extracellular truncation (NEXT), is then cleaved by γ-secretase and the Notch Intra Cellular Domain (NICD) is translocated to the nucleus allowing the transcription of Notch target genes including the Hairy enhancer of split homologs’ transcription factors (Hes and Hey) [18][19] (Figure 1). Low levels of NICD are sufficient to activate transcription because it acts as a transcriptional coactivator on the RBP-JK factor constantly bound to the promoter of target genes [20]. The activation of Notch signaling is finely regulated in different tissues driving organ morphogenesis during development [21]. Figure 1. Notch signaling pathway.Notch receptors are heterodimeric cell membrane proteins containing an extracellular subunit and a fragment that includes a transmembrane and an intracellular domain. Upon binding with ligand expressed on the surface of neighboring cells, two proteolytic cleavages occur. The first one takes place outside the trans-membrane domain by metalloproteinase TACE/ADAM10. The resultant Notch fragment, called Notch extracellular truncation (NEXT), is necessary for the second cleavage performed by γ-secretase within the trans-membrane region. This last proteolytical event releases Notch intracellular domain (NICD) that translocates to the nucleus, interacts with DNA binding proteins CSL (CBF1 Suppressor of Hairless Lag1) otherwise known as RBP-JK and Mastermind (MAML) transactivating target genes.

Figure 1. Notch signaling pathway.Notch receptors are heterodimeric cell membrane proteins containing an extracellular subunit and a fragment that includes a transmembrane and an intracellular domain. Upon binding with ligand expressed on the surface of neighboring cells, two proteolytic cleavages occur. The first one takes place outside the trans-membrane domain by metalloproteinase TACE/ADAM10. The resultant Notch fragment, called Notch extracellular truncation (NEXT), is necessary for the second cleavage performed by γ-secretase within the trans-membrane region. This last proteolytical event releases Notch intracellular domain (NICD) that translocates to the nucleus, interacts with DNA binding proteins CSL (CBF1 Suppressor of Hairless Lag1) otherwise known as RBP-JK and Mastermind (MAML) transactivating target genes.

Notch Signaling in HCC

In the liver, hepatoblasts are the precursors of hepatocytes and cholangiocytes. Notch signaling can inhibit the differentiation of hepatoblasts into hepatocytes, allowing cholangiocyte formation [22][23]. Both the loss and gain of Notch functions may contribute to liver cancer development including both cholangiocarcinoma (CC) and HCC and different Notch receptors have different functions during liver cancer development [24]. Jagged1 plays a central role in the differentiation of hepatocyte progenitor cells (HPCs) and in hepatocyte proliferation during rat liver regeneration suggesting its possible involvement in HCC development [25][26]. Moreover, Jagged1 DNA copy number variation is associated with poor survival after liver cancer surgical resection [27] and its gene expression is comparable to Notch1 expression, suggesting an activation of Notch signaling that might be responsible for HCC development [27][28]. Occurrence of HCC in mice was reported after constitutive activation of NICD. Using bigenic the AFP-Notch Intracellular Domain (AFP-NICD) mice, in which Cre-mediated recombination in embryonic hepatoblasts results in the expression of a constitutively active form of Notch1 in >95% of cholangiocytes and hepatoblasts, Villanueva et al. showed HCC development in 100% of mice [29]. The analysis of differentially expressed genes revealed significant up-regulation of Notch target genes such as Hes1, and Hey2 and the activation of Notch signaling correlated with the transcriptional induction of insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2), an HCC promoter gene [30]. Aberrant Notch expression is frequently found in HCC tissue [31][32][33] where it participates in almost all the hallmarks of cancer, including resistance to anticancer treatments [33]. In line with this, several strategies inhibiting Notch increase treatment efficacy in preclinical models. Among these, γ-secretase inhibition (GSI) represents one the first approaches tested, including in clinical trials [34]. GSIs are a class of small molecules able to prevent the proteolytic cleavage of Notch receptors and the subsequent release of the Notch intracellular domain (NICD), which results from ligand interaction. Remarkably, gamma secretases are membrane-bound proteases involved in the cleavage of several other substrates including the beta-amyloid precursor, which accounts for their use in Alzheimer’s disease. Due to the pan-inhibition nature of GSIs, adverse effects have been described in clinical trials on advanced tumors, such as gastro-intestinal side effects, resulting from the blocking of the high constitutive expression of Notch in the GI tract. The poor results obtained in clinical trials in terms of tumor shrinkage or overall-survival (OS) might be related both to the absence of molecularly-based inclusion criteria and to the blockade of all four Notch receptors irrespective of their ligands. Indeed, experimental evidence shows that each Notch receptor is involved in specific and different functions. In addition, the downstream effects of Notch activation are strongly influenced by the interaction with specific ligands. Thus, alternative strategies have been considered, such as monoclonal antibodies targeting single Notch receptors or specific ligands. Many reviews have already summarized the current knowledge of Notch signaling in HCC development and have outlined the therapeutic potential of targeting Notch signaling in HCC [35][36][37]. Importantly, Notch plays pleomorphic roles in HCC, which relies both on the aberrant expression of specific Notch receptors and on their activation by specific ligands. A precise knowledge on the deregulated expression of each Notch receptor and ligand, coupled with phenotypic changes, is still lacking in HCC. This hampers the development of molecularly-targeted approaches. Notwithstanding, given the relevance of Notch aberrant activation in HCC, also in terms of resistance to treatments, this pathway is very attractive when hypothesizing combined treatment. Thus, in this review we highlighted the mechanisms involved in Notch signaling pathway regulation which might deserve attention when planning therapeutic strategies modulating Notch.

References

- Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Dikshit, R.; Eser, S.; Mathers, C.; Rebelo, M.; Parkin, D.M.; Forman, D.; Bray, F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, E359–E386.

- Kulik, L.; El-Serag, H.B. Epidemiology and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 477–491.e1.

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic Address EEE, European Association for the Study of the L. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 182–236.

- Llovet, J.M.; Ricci, S.; Mazzaferro, V.; Hilgard, P.; Gane, E.; Blanc, J.F.; De Oliveira, A.C.; Santoro, A.; Raoul, J.L.; Forner, A.; et al. Sorafenib in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 378–390.

- Wilhelm, S.M.; Adnane, L.; Newell, P.; Villanueva, A.; Llovet, J.M.; Lynch, M. Preclinical Overview of Sorafenib, a Multikinase Inhibitor That Targets Both Raf and VEGF and PDGF Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Signaling. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008, 7, 3129–3140.

- Kudo, M.; Finn, R.S.; Qin, S.; Han, K.-H.; Ikeda, K.; Piscaglia, F.; Baron, A.; Park, J.-W.; Han, G.; Jassem, J.; et al. Lenvatinib versus Sorafenib in First-Line Treatment of Patients with Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Randomised Phase 3 Non-inferiority Trial. Lancet 2018, 391, 1163–1173.

- Da Fonseca, L.G.; Reig, M.; Bruix, J. Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin. Liver Dis. 2020, 24, 719–737.

- Constantinidou, A.; Alifieris, C.; Trafalis, D.T. Targeting Programmed Cell Death-1 (PD-1) and Ligand (PD-L1): A New Era in Cancer Active Immunotherapy. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 194, 84–106.

- Duffy, A.G.; Ulahannan, S.V.; Makorova-Rusher, O.; Rahma, O.; Wedemeyer, H.; Pratt, D.; Davis, J.L.; Hughes, M.S.; Heller, T.; ElGindi, M.; et al. Tremelimumab in Combination with Ablation in Patients with Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2017, 66, 545–551.

- Finn, R.S.; Qin, S.; Ikeda, M.; Galle, P.R.; Ducreux, M.; Kim, T.-Y.; Kudo, M.; Breder, V.; Merle, P.; Kaseb, A.O. Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1894–1905.

- Moeini, A.; Cornella, H.; Villanueva, A. Emerging Signaling Pathways in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Liver Cancer 2012, 1, 83–93.

- Radtke, F.; Fasnacht, N.; MacDonald, H.R. Notch Signaling in the Immune System. Immunity 2010, 32, 14–27.

- Morgan, T.H. The Origin of Nine Wing Mutations in Drosophila. Science 1911, 33, 496–499.

- Wharton, K.A.; Johansen, K.M.; Xu, T.; Artavanis-Tsakonas, S. Nucleotide Sequence from the Neurogenic Locus Notch Implies a Gene Product That Shares Homology with Proteins Containing EGF-Like Repeats. Cell 1985, 43, 567–581.

- Miller, A.C.; Lyons, E.L.; Herman, T.G. Cis-Inhibition of Notch by Endogenous Delta Biases the Outcome of Lateral Inhibition. Curr. Biol. 2009, 19, 1378–1383.

- Luo, Y.; Haltiwanger, R.S. O-Fucosylation of Notch Occurs in the Endoplasmic Reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 11289–11294.

- Blaumueller, C.M.; Qi, H.; Zagouras, P.; Artavanis-Tsakonas, S. Intracellular Cleavage of Notch Leads to a Heterodimeric Receptor on the Plasma Membrane. Cell 1997, 90, 281–291.

- Kopan, R. Notch Signaling. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012, 4, a011213.

- Borggrefe, T.; Oswald, F. The Notch Signaling Pathway: Transcriptional Regulation at Notch Target Genes. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2009, 66, 1631–1646.

- Schroeter, E.H.; Kisslinger, J.A.; Kopan, R. Notch-1 Signalling Requires Ligand-Induced Proteolytic Release of Intracellular Domain. Nat. Cell Biol. 1998, 393, 382–386.

- Siebel, C.; Lendahl, U. Notch Signaling in Development, Tissue Homeostasis, and Disease. Physiol. Rev. 2017, 97, 1235–1294.

- Gil-García, B.; Baladrón, V. The Complex Role of NOTCH Receptors and Their Ligands in the Development of Hepatoblastoma, Cholangiocarcinoma and Hepa-Tocellular Carcinoma. Biol. Cell 2015, 108, 29–40.

- Rauff, B.; Malik, A.; Bhatti, Y.A.; Chudhary, S.A.; Qadri, I.; Rafiq, S. Notch Signalling Pathway in Development of Cholangiocarcinoma. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2020, 12, 957–974.

- Huntzicker, E.G.; Hötzel, K.; Choy, L.; Che, L.; Ross, J.; Pau, G.; Sharma, N.; Siebel, C.W.; Chen, X.; French, D.M. Differential Effects of Targeting Notch Receptors in a Mouse Model of Liver Cancer. Hepatology 2015, 61, 942–952.

- Gao, J.; Chen, C.; Hong, L.; Wang, J.; Du, Y.; Song, J.; Shao, X.; Zhang, J.; Han, H.; Liu, J.; et al. Expression of Jagged1 and its Association with Hepatitis B Virus X Protein in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 356, 341–347.

- Paranjpe, S.; Bowen, W.C.; Bell, A.W.; Nejak-Bowen, K.; Luo, J.-H.; Michalopoulos, G.K. Cell Cycle Effects Resulting from Inhibition of Hepatocyte Growth Factor and Its Receptor C-Met in Regenerating Rat Livers by RNA Interference. Hepatology 2007, 45, 1471–1477.

- Kawaguchi, K.; Honda, M.; Yamashita, T.; Okada, H.; Shirasaki, T.; Nishikawa, M.; Nio, K.; Arai, K.; Sakai, Y.; Yamashita, T.; et al. Jagged1 DNA Copy Number Variation Is Associated with Poor Outcome in Liver Cancer. Am. J. Pathol. 2016, 186, 2055–2067.

- Wang, M.; Xue, L.; Cao, Q.; Lin, Y.; Ding, Y.; Yang, P.; Che, L. Expression of Notch1, Jagged1 and β-Catenin and Their Clinicopathological Significance in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Neoplasma 2009, 56, 533–541.

- Villanueva, A.; Alsinet, C.; Yanger, K.; Hoshida, Y.; Zong, Y.; Toffanin, S.; Rodriguez–Carunchio, L.; Solé, M.; Thung, S.; Stanger, B.Z.; et al. Notch Signaling Is Activated in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Induces Tumor Formation in Mice. Gastroenterology 2012, 143, 1660–1669.e7.

- Tovar, V.; Alsinet, C.; Villanueva, A.; Hoshida, Y.; Chiang, D.Y.; Solé, M.; Thung, S.; Moyano, S.; Toffanin, S.; Mínguez, B.; et al. IGF Activation in a Molecular Subclass of Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Pre-Clinical Efficacy of IGF-1R Blockage. J. Hepatol. 2010, 52, 550–559.

- Giovannini, C.; Gramantieri, L.; Chieco, P.; Minguzzi, M.; Lago, F.; Pianetti, S.; Ramazzotti, E.; Marcu, K.B.; Bolondi, L. Selective Ablation of Notch3 in HCC Enhances Doxorubicin’s Death Promoting Effect by a p53 Dependent Mechanism. J. Hepatol. 2009, 50, 969–979.

- Gramantieri, L.; Giovannini, C.; Lanzi, A.; Chieco, P.; Ravaioli, M.; Venturi, A.; Grazi, G.L.; Bolondi, L. Aberrant Notch3 and Notch4 Expression in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Liver Int. 2007, 27, 997–1007.

- Zhang, Q.; Lu, C.; Fang, T.; Wang, Y.; Hu, W.; Qiao, J.; Liu, B.; Liu, J.; Chen, N.; Li, M.; et al. Notch3 Functions as a Regulator of Cell Self-Renewal by Interacting with the β-Catenin Pathway in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 3669–3679.

- Moore, G.; Annett, S.; McClements, L.; Robson, T. Top Notch Targeting Strategies in Cancer: A Detailed Overview of Recent Insights and Current Perspectives. Cells 2020, 9, 1503.

- Morell, C.M.; Fiorotto, R.; Fabris, L.; Strazzabosco, M. Notch Signalling beyond Liver Development: Emerging Concepts in Liver Repair and Oncogenesis. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2013, 37, 447–454.

- Huang, Q.; Li, J.; Zheng, J.; Wei, A. The Carcinogenic Role of the Notch Signaling Pathway in the Development of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Cancer 2019, 10, 1570–1579.

- Giovannini, C.; Bolondi, L.; Gramantieri, L. Targeting Notch3 in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 18, 56.