| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Steven Mitchell | + 2396 word(s) | 2396 | 2021-03-23 04:23:37 | | | |

| 2 | Vivi Li | -1 word(s) | 2395 | 2021-03-31 06:01:17 | | |

Video Upload Options

Parkinson’s disease is the most common age-related motoric neurodegenerative disease. In addition to the cardinal motor symptoms of tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural instability, there are numerous non-motor symptoms as well. Among the non-motor symptoms, autonomic nervous system dysfunction is common. Autonomic symptoms associated with Parkinson’s disease include sialorrhea, hyperhidrosis, gastrointestinal dysfunction, and urinary dysfunction. Botulinum neurotoxin has been shown to potentially improve these autonomic symptoms.

1. Introduction

First described in 1817 by James Parkinson in his work “An Essay on the Shaking Palsy” [1], Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the most common age-related motoric neurodegenerative disease [2][3][4]. Estimates indicate that in 2010 the prevalence of PD in those over age 45 was 680,000 in the United States, with that number estimated to rise to 1,238,000 in 2030 [5]. The four cardinal features of PD are resting tremor, rigidity (i.e., increased resistance throughout the range of passive limb movement), bradykinesia (i.e., slowness of movement), and postural instability [6][7][8]. The non-motor aspects of PD include a variety of domains such as sleep disorders, pain, cognitive dysfunction, and autonomic dysfunction (i.e., dysautonomia) [2][7][9].

Idiopathic PD has traditionally been considered the most common form of parkinsonism [7][10][11]. More recently, however, the concept of idiopathic PD as a single entity has been challenged [7][8][12]. As we learn more about clinical subtypes, pathogenic genes, and possible causative environmental agents of PD, it seems logical that PD is more diagnostically complex than initially thought [7][12][13].

Pathologically, PD is associated with Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites consisting of misfolded and aggregated alpha-synuclein protein [7][14][15]. Physiologically, PD results in loss of dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta and subsequent basal ganglia dysfunction [4][15], as well as reduction in mitochondrial activity [4][7][16]. In addition, it has been found that disruption of non-dopaminergic pathways (e.g., noradrenergic, glutamatergic, serotonergic, and adenosine pathways) also occurs in PD and may account for the various non-motor symptoms [7][17].

Carbidopa-levodopa is considered the gold standard treatment for PD and mainly acts by replenishing dopamine in the nigrostriatal pathway [2][7][18]. Carbidopa-levodopa improves motor symptoms to a variable extent but does not substantially affect non-motor aspects of the disease [7][19][20]. With prolonged use, patients become less responsive to dopaminergic agents and experience a narrowing therapeutic window with side effects such as motor fluctuations, dyskinesias, autonomic nervous system dysfunction, and various neuropsychiatric symptoms [7][18][21]. Alternative therapies for PD include dopamine agonists, anticholinergics, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), catechol-O-methyl transferase inhibitors (COMTIs), deep brain stimulation, focused ultrasound lesioning, and botulinum neurotoxins [2][7][8][22].

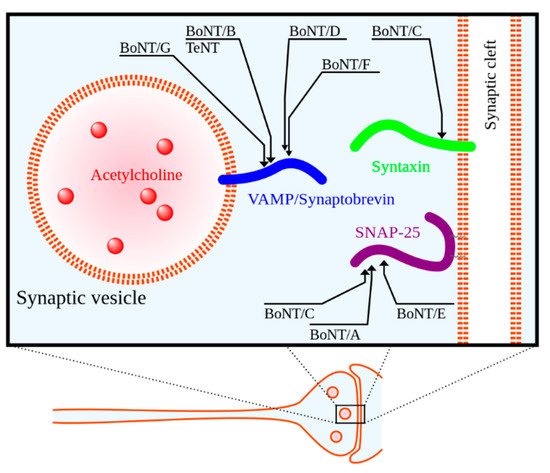

Botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT), regarded as the most potent toxin known to mankind, is produced by the anaerobic spore-forming Gram-positive bacillus Clostridium botulinum [23][24][25]. BoNT is a zinc protease that cleaves neuronal vesicle-associated proteins responsible for acetylcholine release into the neuromuscular junction [23]. See Figure 1 for a depiction of the mechanism of action. BoNT was first approved for medical use in Canada in the late 1980s for the treatment of strabismus (i.e., eye misalignment) [23]. FDA approval for clinical use of BoNT in the United States for strabismus and blepharospasm was subsequently granted in 1989 [23]. Since that time, the indications and use of BoNT have expanded.

Figure 1. Molecular targets of clostridial neurotoxins in presynaptic cell. BoNT/A–G = botulinum toxin serotypes A–G, TeNT = tetanus toxin. Reproduced from Wikipedia Commons. Adapted by Y tambe from [26]. 2005, Emerg. Infect. Dis.

There are seven biological serotypes of BoNT, with two of these serotypes used in clinical practice [24][25]. BoNT serotypes A and B, of which there are four formulations currently on the market, are used for a variety of medical indications including glabellar lines (i.e., facial wrinkles), dystonia (a disorder of involuntary muscle contractions causing repetitive or twisting movements), spasticity, and migraines [24][25][27][28]. See Table 1 for a summary of the four BoNT formulations currently available.

Table 1. Summary of botulinum neurotoxin formulations currently available for clinical use. Adapted from a review by Shukla and Malaty [27].

|

Toxin Property |

OnabotulinumtoxinA |

AbobotulinumtoxinA |

RimabotulinumtoxinB |

IncobotulinmtoxinA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Year introduced |

1989 |

1991 |

2000 |

2005 |

|

Trade name |

BOTOX® |

Dysport® |

Myobloc/NeuroBloc® |

Xeomin® |

|

Mechanism of action |

Cleaves SNAP 25 |

Cleaves SNAP 25 |

Cleaves VAMP |

Cleaves SNAP 25 |

|

Molecular weight (kD) |

900 |

500–900 |

700 |

150 |

|

Total protein (ng/vial) |

~5 |

~5 |

~50 |

~0.6 |

|

Units/vial |

50, 100, or 200 |

300 or 500 |

2500, 5000, or 10,000 |

50 or 100 |

|

Shelf life (months) |

36 |

24 |

24 |

36 |

|

Formulation |

Vacuum dried |

Freeze dried |

Sterile solution |

Freeze dried |

|

pH after reconstitution |

7.4 |

7.4 |

5.6 |

7.4 |

|

FDA-approved uses (in adults unless indicated) |

Cervical dystonia (16 years and up), blepharospasm (12 years and up), hyperactive bladder, upper and lower limb spasticity, strabismus (12 years and up), glabellar lines, axillary hyperhidrosis, and chronic migraine |

Cervical dystonia, glabellar lines, upper limb spasticity, and lower limb spasticity (2 years and up) |

Cervical dystonia and chronic sialorrhea |

Cervical dystonia, chronic sialorrhea, blepharospasm, and upper limb spasticity (2 years and up) |

|

Off-label uses |

Sialorrhea, hemifacialspasm, focal limb dystonia, oromandibular dystonia, tremors, tics, and tardive dyskinesia |

Sialorrhea, focal limb dystonia, oromandibular dystonia, and tremors |

Focal limb dystonia and oromandibular dystonia |

Focal limb dystonia and oromandibular dystonia |

Abbreviations: FDA = Food and Drug Administration, SNAP 25 = synaptosomal-associated protein 25, VAMP = vesicle associated membrane protein.

2. Botulinum Neurotoxin for Sialorrhea

Sialorrhea, otherwise known as excessive salivation or drooling, is a common non-motor symptom seen in approximately 50–70% of PD patients [29][30]. Sialorrhea is likely multifactorial and is thought to occur from either increased saliva secretion or inadequate clearance [27]. Dysphagia, or difficulty swallowing, can contribute to inadequate clearance and is likely the primary mechanism of drooling in PD [30]. In addition, patients with more advanced stages of PD often exhibit a flexed neck posture, which in conjunction with an open jaw can contribute to drooling [27][30]. Excessive drooling can unfortunately lead to social embarrassment and worsening depression [31], as well as poor oral and perioral hygiene and respiratory tract infections [30].

Ultrasound (US)-guided injection of BoNT into parotid and submandibular glands can be recommended as first line treatment for sialorrhea, especially when anticholinergic oral medications are not indicated due to the risk of confusion, cognitive decline, or psychosis [32][30]. Oral glycopyrrolate, a muscarinic anticholinergic, can be used for sialorrhea [31], however, long-term studies on it are lacking [29]. Sublingual atropine 1% has also been suggested as an alternative therapy for sialorrhea in PD [33], however, no randomized controlled trials have been carried out.

Several recent studies have confirmed the efficacy of BoNT for sialorrhea [34][35][36]. A small study in 2018 showed efficacy of incobotulinumtoxinA for reducing sialorrhea in children with post-anoxic cerebral palsy [35]. An earlier retrospective cohort study of 45 neurologically impaired children also found that US-guided BoNT type A injections into the salivary glands was safe and efficacious for drooling, with an approximately 5 month mean duration of effect [36] and onset of action approximately 1 week following BoNT injection [30]. In a systematic review by Seppi and colleagues, BoNT type A and type B were both deemed efficacious and with acceptable risk on the basis of well-designed randomized clinical trials for the treatment of drooling in PD patients when administered by well-trained physicians with specialized monitoring techniques, such as US guidance [34].

As with any invasive procedure, infection, hematoma, and pain are known risks of BoNT injection [37]. A single case report of parotitis and sialolithiasis (i.e., salivary gland stones) following injection with rimabotulinumtoxinB was found in our literature review [37]. In addition, BoNT injection into the parotid and submandibular glands may lead to transient dysphagia [30] or xerostomia (i.e., dry mouth) [38]. Nevertheless, a study conducted in 2017 by Tiigimäe-Saar and colleagues indicates that use of BoNT (particularly BoNT type A) can effectively slow salivary flow rate without changing the salivary composition. This indicates that BoNT can effectively treat sialorrhea without impacting the oral health of the patient [39].

3. Botulinum Neurotoxin for Hyperhidrosis

Hyperhidrosis, defined as excessive sweating, has been reported in 65% of patients with PD [40]. Those PD patients with chronic hyperhidrosis tend to have a higher burden of autonomic symptoms [41][42] as well as higher dyskinesia scores, higher depression and anxiety, and worse quality of life [42]. Hyperhidrosis is usually related to off states or to severe dyskinesia with high energy output [30]. Carbidopa-levodopa and dopamine agonists, two of the most common classes of medications used to treat PD, unfortunately have sweating as a potential side effect as well [7].

Recent reviews highlight the fact that no randomized controlled trials on the use of BoNT for hyperhidrosis in PD have been performed [34][30][40]. Nevertheless, the use of BoNT type A for the treatment of axillary hyperhidrosis has a level A (i.e., established as effective) recommendation [25][27][30][40]. Following local anesthesia, intradermal BoNT injections of the axilla may be performed. By blocking acetylcholine release from sympathetic nerve fibers, BoNT effectively denervates eccrine sweat glands [30]. Treatment is effective for up to 9 months [30]. It is important to note that hyperhidrosis in PD is usually generalized in nature [30], and given the focal nature of BoNT injections, this treatment will only be effective in regions treated.

4. Botulinum Neurotoxin for Gastrointestinal Dysfunction

Gastrointestinal (GI) dysfunction in PD includes dysphagia (i.e., difficulty swallowing), gastroparesis (i.e., delayed gastric emptying), and constipation [43][44][30][38]. Some have proposed that abnormal accumulations of alpha-synuclein in the periphery may account for the GI dysfunctions observed in PD patients [43][44][45], and the much-debated Braak hypothesis proposes that sporadic PD originates from Lewy pathology in the GI tract [46]. BoNT can be useful for dysphagia, gastroparesis, and constipation.

Dysphagia may lead to aspiration and subsequent pneumonia [47], which unfortunately is a leading cause of death in PD [48]. Dysphagia may be classified as either oropharyngeal or esophageal in etiology [43]. Oropharyngeal dysphagia is estimated to occur in up to 80% of PD patients, while esophageal dysphagia is probably less common [43]. BoNT may be useful for both types [49][43][38]. BoNT injection of the cricopharyngeal muscle has shown benefit for oropharyngeal dysphagia, as evidenced by videofluoroscopy or high-resolution pharyngeal manometry [43][38], while BoNT injection of the lower esophagus and esophago-gastric junction has shown benefit for esophageal dysphagia [49][43]. Benefits from cricopharyngeal muscle injection can last 16–20 weeks [38], and favorable response to percutaneous injection of BoNT type A into the cricopharyngeal muscle may be a useful tool in identifying patients who could benefit from surgical myotomy [47].

Gastroparesis in the form of nausea and vomiting occurs in approximately 25% of PD patients, while abdominal bloating is reported in up to 45% of PD patients [43]. Gastroparesis may not only affect nutrition but also secondarily cause delayed absorption of oral levodopa leading to worsening of motor fluctuations [43][30]. Endoscopic injection of 100–200 units of BoNT into the pylorus of nine PD patients by Triadafilopoulos and colleagues resulted in subjective improvement in early satiety, bloating, epigastric pain, and nausea [49]. As noted by Sławek and colleagues, earlier studies using onabotulinumtoxinA and incobotulinumtoxinA injection of the pylorus also showed possible benefit in a small number of PD patients, but no double-blinded randomized controlled studies have confirmed these findings [30].

Constipation affects approximately 60% of PD patients [43][38]. Constipation in PD likely occurs from either slow transit, outlet obstruction from focal dystonia of pelvic floor muscles, or a combination of both [43][50][38]. Importantly, constipation is considered a prodromal symptom in PD and may predate onset of motor symptoms by up to 16 years [41][51]. As noted in a review by Jocson and colleagues, two small open label studies in the early 2000s suggested that onabotulinumtoxinA injection of the puborectalis muscle is effective for constipation from outlet-type obstruction [38]. The study by Triadafilopoulos and colleagues included two patients who received BoNT injection of the anal sphincter or puborectalis muscle, one with improvement in constipation from paradoxical anal contraction and the other with improvement in constipation from slow transit [49]. Fecal incontinence is a potential side effect of BoNT injection into these muscles [30].

5. Botulinum Neurotoxin for Urinary Dysfunction

Prevalence of urinary dysfunction in PD patients is estimated to be as low as 35% [40] or as high as 64–67% [38][41]. Lower urinary tract symptoms include both dysfunction of urinary storage and urinary voiding [52]. Storage symptoms include urgency, frequency, and nocturia (i.e., frequent urination at night), while voiding symptoms include slow or interrupted stream, terminal dribble, hesitancy, and straining [29][52]. Neurogenic overactive bladder manifesting as nocturia is the most reported urinary symptom in PD patients [30][38]. Complications from urinary tract dysfunction include upper urinary tract damage and recurrent urinary tract infections [53]. Detrusor muscle overactivity and detrusor-sphincter dyssynergy are frequently implicated [27][54][53].

OnabotulinumtoxinA is an effective and approved treatment for neurogenic detrusor overactivity when antimuscarinic medications are not effective or cause side effects [55][56][53][57]. Intradetrusor injection with up to 360 units of onabotulinumtoxinA may be administered as frequently as every 3 months [53], although effects may last up to 9 months [56][30]. Transient urinary retention following BoNT injection of the detrusor muscle is a potential complication and may require intermittent or indwelling catheterization [55][53][40]. A 2016 phase 3 clinical trial of abobotulinumtoxinA for the treatment of neurogenic detrusor overactivity appears to have been terminated in 2019 due to low patient recruitment [58].

Interestingly, a recent cross-sectional study of over 300 PD patients found that despite no difference in overall urinary symptom prevalence, men with PD are more likely than women to receive a medication, such as BoNT, for urinary symptom treatment [59]. Miller-Patterson and colleagues suggest that men may be more likely than women to be screened for urinary dysfunction, however, the reasons for this disparity are ultimately unclear [59].

6. Botulinum Neurotoxin for Pain

Pain is unfortunately a commonly reported symptom in patients with PD [20][60][61][62]. One 2008 study conducted in Norway found that pain was reported by more than 80% of PD patients (n = 146), with these patients experiencing significantly more pain than the general population [63]. Pain in PD is usually multifactorial and can include musculoskeletal pain, dystonic pain, neuropathic pain, and central pain [60][61]. The mechanisms of pain in PD are complex and poorly understood [64], but musculoskeletal pain and dystonic pain seem to be the most common etiologies [30], with the former typically related to rigidity or motor fluctuations and the latter more commonly associated with end-of-medication or peak-of-medication dosing [60]. BoNT has been shown to alleviate some PD related pain symptoms, particularly painful dystonia [65].

A small randomized controlled crossover study in 2017 showed a mild but non-significant reduction in musculoskeletal and dystonic pain 4 weeks after treatment with BoNT type A, with even greater but still non-significant reduction in dystonic pain on subgroup analysis [66]. In another randomized placebo-controlled trial, injection of incobotulinumtoxinA with 100 units into either the flexor digitorum brevis or flexor digitorum longus was effective in reducing pain associated with plantar flexion of toe dystonia [67]. Finally, as discussed previously, BoNT can help with painful myotonus or spasms in the esophagus, pylorus, anal sphincter, and detrustor muscle [68].

7. Botulinum Neurotoxin for Other Indications

It is worth noting that BoNT may be useful for the motor aspects of PD as well [24][25][27][69]. BoNT is increasingly being used for additional PD-related indications including blepharospasm (i.e., involuntary eyelid closure), oromandibular dystonia, cervical dystonia, limb dystonia, and tremors [27][69]. Although more common in atypical parkinsonism, blepharospasm can be seen in patients with idiopathic PD [70][71]. BoNT injection of the orbicularis oculi is effective and represents the first-line therapy for blepharospasm [72][73].

References

- Parkinson, J. An essay on the shaking palsy 1817. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2002, 14, 223–236.

- Mhyre, T.R.; Boyd, J.T.; Hamill, R.W.; Maguire-Zeiss, K.A. Parkinson’s disease. Subcell Biochem. 2012, 65, 389–455.

- Gitler, A.D.; Dhillon, P.; Shorter, J. Neurodegenerative disease: Models, mechanisms, and a new hope. Dis. Models Mech. 2017, 10, 499–502.

- Reeve, A.; Simcox, E.; Turnbull, D. Ageing and Parkinson’s disease: Why is advancing age the biggest risk factor? Ageing Res. Rev. 2014, 14, 19–30.

- Marras, C.; Beck, J.C.; Bower, J.H.; Roberts, E.; Ritz, B.; Ross, G.; Tanner, C.M.; on behalf of the Parkinson’s Foundation P4 Group. Prevalence of Parkinson’s disease across North America. NPJ Parkinson’s Dis. 2018, 4, 1–7.

- Jankovic, J. Parkinson’s disease: Clinical features and diagnosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2008, 79, 368–376.

- Jankovic, J.; Tan, E.K. Parkinson’s disease: Etiopathogenesis and treatment. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2020, 91, 8.

- Armstrong, M.J.; Okun, M.S. Diagnosis and treatment of Parkinson disease. JAMA 2020, 323, 548–560.

- Pfeiffer, R.F. Non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2016, 22, S119–S122.

- Aerts, M.B.; Esselink, R.A.J.; Post, B.; van de Warrenburg, B.P.; Bloem, B.R. Improving the diagnostic accuracy in parkinsonism: A three-pronged approach. Pract. Neurol. 2012, 12, 77–87.

- Munhoz, R.P.; Werneck, L.C.; Teive, H.A.G. The differential diagnoses of parkinsonism: Findings from a cohort of 1528 patients and a 10 years comparison in tertiary movement disorders clinics. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2010, 112, 431–435.

- Espay, A.J.; Schwarzschild, M.A.; Tanner, C.M.; Fernandez, H.H.; Simon, D.K.; Leverenz, J.B.; Lang, A.E. Biomarker-driven phenotyping in Parkinson’s disease: A translational missing link in disease-modifying clinical trials. Mov. Disord. 2017, 32, 319–324.

- Trifonova, O.P.; Maslov, D.L.; Balashova, E.E.; Urazgildeeva, G.R.; Abaimov, D.A.; Fedotova, E.Y.; Lokhov, P.G. Parkinson’s disease: Available clinical and promising omics tests for diagnostics, disease risk assessment, and pharmacotherapy personalization. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 339.

- Espay, A.J.; Vizcarra, J.A.; Marsili, L.; Lang, A.E.; Simon, D.K.; Merola, A.; Leverenz, J.B. Revisiting protein aggregation as pathogenic in sporadic Parkinson and Alzheimer diseases. Neurology 2019, 92, 329–337.

- Giguère, N.; Burke Nanni, S.; Trudeau, L.E. On cell loss and selective vulnerability of neuronal populations in Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurol. 2018, 19, 455.

- Annesley, S.J.; Lay, S.T.; De Piazza, S.W.; Sanislav, O.; Hammersley, E.; Allan, C.Y.; Fisher, P.R. Immortalized Parkinson’s disease lymphocytes have enhanced mitochondrial respiratory activity. Dis. Models Mech. 2016, 9, 1295–1305.

- Chaudhuri, K.R.; Sauerbier, A. Unravelling the nonmotor mysteries of Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2016, 12, 10–11.

- Pezzoli, G.; Zini, M. Levodopa in Parkinson’s disease: From the past to the future. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2010, 11, 627–635.

- Fabbri, M.; Coelho, M.; Guedes, L.C.; Chendo, I.; Sousa, C.; Rosa, M.M.; Ferreira, J.J. Response of non-motor symptoms to levodopa in late-stage Parkinson’s disease: Results of a levodopa challenge test. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2017, 39, 37–43.

- Rana, A.Q.; Ahmed, U.A.; Chaudry, Z.M.; Vasan, S. Parkinson’s disease: A review of non-motor symptoms. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2015, 15, 549–562.

- Heusinkveld, J.E.; Hacker, M.L.; Turchan, M.; Davis, T.L.; Charles, D. Impact of tremor on patients with early stage Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 628.

- Emamzadeh, F.N.; Surguchov, A. Parkinson’s disease: Biomarkers, treatment, and risk factors. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 612.

- Dhaked, R.K.; Singh, M.K.; Singh, P.; Gupta, P. Botulinum toxin: Bioweapon & magic drug. Indian J. Med. Res. 2010, 132, 489–503.

- Jankovic, J. Botulinum toxin: State of the art. Mov. Disord. 2017, 32, 1131–1138.

- Mills, R.; Bahroo, L.; Pagan, F. An update on the use of botulinum toxin therapy in Parkinson’s disease. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2015, 15, 511.

- Barr, J.R.; Moura, H.; Boyer, A.E.; Woolfitt, A.R.; Kalb, S.R.; Pavlopoulos, A. Botulinum neurotoxin detection and differentiation by mass spectrometry. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005, 11, 1578–1583.

- Shukla, A.W.; Malaty, I.A. Botulinum toxin therapy for Parkinson’s disease. Semin Neurol. 2017, 37, 193–204.

- Abrams, S.B.; Hallett, M. Clinical utility of different botulinum neurotoxin preparations. Toxicon 2013, 67, 81–86.

- Kulshreshtha, D.; Ganguly, J.; Jog, M. Managing autonomic dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: A review of emerging drugs. Expert Opin. Emerg. Drugs 2020, 25, 37–47.

- Sławek, J.; Madaliński, M. Botulinum toxin therapy for nonmotor aspects of Parkinson’s disease. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2017, 134, 1111–1142.

- Quarracino, C.; Otero-Losada, M.; Capani, F.; Pérez-Lloret, S. State-of-the-art pharmacotherapy for autonomic dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2020, 21, 445–457.

- Hayes, M.W.; Fung, V.S.C.; Kimber, T.E.; O’Sullivan, J.D. Updates and advances in the treatment of Parkinson disease. Med. J. Aust. 2019, 211, 277–283.

- Papesh, K.; Nguyen, J. Atropine as alternate therapy for treatment of sialorrhea in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2019, 34 (Suppl. 2), S72–S73.

- Seppi, K.; Ray Chaudhuri, K.; Coelho, M.; Fox, S.H.; Katzenschlager, R.; Perez Lloret, S.; Djamshidian-Tehrani, A. Update on treatments for nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease—An evidence-based medicine review. Mov. Disord. 2019, 34, 180–198.

- Foresti, C.; Stabile, A. Botulinum toxin treatment of sialorrhea in children. Toxicon 2018, 156 (Suppl. 1), S34–S35.

- Khan, W.U.; Campisi, P.; Nadarajah, S.; Shakur, Y.A.; Khan, N.; Semenuk, D.; Connolly, B. Botulinum toxin A for treatment of sialorrhea in children: An effective, minimally invasive approach. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2011, 137, 339–344.

- Papesh, K.; Nguyen, J. Parotitis as adverse event following BoNT injections for sialorrhea. Mov. Disord. 2019, 34 (Suppl. 2), S72.

- Jocson, A.; Lew, M. Use of botulinum toxin in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2019, 59, 57–64.

- Tiigimäe-Saar, J.; Tamme, T.; Taba, P. Saliva changes and the oral health in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2017, 32 (Suppl. 2), 35.

- Tater, P.; Pandey, S. Botulinum toxin in movement disorders. Neurol. India 2018, 66, S79–S89.

- Chen, Z.; Li, G.; Liu, J. Autonomic dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: Implications for pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020, 134, 104700.

- Van Wamelen, D.J.; Leta, V.; Podlewska, A.M.; Wan, Y.M.; Krbot, K.; Jaakkola, E.; Chaudhuri, K.R. Exploring hyperhidrosis and related thermoregulatory symptoms as a possible clinical identifier for the dysautonomic subtype of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. 2019, 266, 1736–1742.

- Ramprasad, C.; Douglas, J.Y.; Moshiree, B. Parkinson’s disease and current treatments for its gastrointestinal neurogastromotility effects. Curr. Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2018, 16, 489–510.

- Mendoza-Velásquez, J.J.; Flores-Vázquez, J.F.; Barrón-Velázquez, E.; Sosa-Ortiz, A.L.; Illigens, B.M.W.; Siepmann, T. Autonomic dysfunction in α-synucleinopathies. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 363.

- Nóbrega, A.C.; Rodrigues, B.; Torres, A.C.; Scarpel, R.D.A.; Neves, C.A.; Melo, A. Is drooling secondary to a swallowing disorder in patients with Parkinson’s disease? Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2008, 14, 243–245.

- Braak, H.; de Vos, R.A.; Bohl, J.; Del Tredici, K. Gastric alpha-synuclein immunoreactive inclusions in Meissner’s and Auerbach’s plexuses in cases staged for Parkinson’s disease-related brain pathology. Neurosci. Lett. 2006, 396, 67–72.

- Barbagelata, E.; Nicolini, A.; Tognetti, P. Swallowing dysfunctions in Parkinson’s disease patients: A novel challenge for the internist. Ital. J. Med. 2019, 13, 91–94.

- Akbar, U.; Dham, B.; He, Y. Trends of aspiration pneumonia in Parkinson’s disease in the United States, 1979–2010. Parkinson Relat. Disord. 2015, 21, 1082–1086.

- Triadafilopoulos, G.; Gandhy, R.; Barlow, C. Pilot cohort study of endoscopic botulinum neurotoxin injection in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2017, 44, 33–37.

- Sharma, A.; Kurek, J.; Morgan, J.C.; Wakade, C.; Rao, S.S.C. Constipation in Parkinson’s disease: A nuisance or nuanced answer to the pathophysiological puzzle? Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2018, 20, 1.

- Fereshtehnejad, S.M.; Yao, C.; Pelletier, A.; Montplaisir, J.Y.; Gagnon, J.F.; Postuma, R.B. Evolution of prodromal Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies: A prospective study. Brain J. Neurol. 2019, 142, 2051–2067.

- McDonald, C.; Winge, K.; Burn, D.J. Lower urinary tract symptoms in Parkinson’s disease: Prevalence, aetiology and management. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2017, 35, 8–16.

- Mehnert, U.; Chartier-Kastler, E.; de Wachter, S.; van Kerrebroeck, P.E.V.A.; van Koeveringe, G.A. The management of urine storage dysfunction in the neurological patient. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2019, 3, 160–182.

- Sakakibara, R.; Tateno, F.; Yamamoto, T.; Uchiyama, T.; Yamanishi, T. Urological dysfunction in synucleinopathies: Epidemiology, pathophysiology and management. Clin. Auton. Res. 2018, 28, 83–101.

- Brucker, B.M.; Kalra, S. Parkinson’s disease and its effect on the lower urinary tract: Evaluation of complications and treatment strategies. Urol. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 44, 415–428.

- Madan, A.; Ray, S.; Burdick, D.; Agarwal, P. Management of lower urinary tract symptoms in Parkinson’s disease in the neurology clinic. Int. J. Neurosci. 2017, 127, 1136–1149.

- Jost, W.H. Autonomic dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: Cardiovascular symptoms, thermoregulation, and urogenital symptoms. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2017, 134, 771–785.

- ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). Identifier NCT02660359. Dysport® Treatment of Urinary Incontinence in Adults Subjects With Neurogenic Detrusor Overactivity (NDO) Due to Spinal Cord Injury or Multiple Sclerosis—Study 2 (CONTENT2). 21 January 2016. Available online: (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Miller-Patterson, C.; Edwards, K.A.; Chahine, L.M. Sex disparities in autonomic symptom treatment in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2020, 7, 718–719.

- Karnik, V.; Farcy, N.; Zamorano, C.; Bruno, V. Current status of pain management in Parkinson’s disease. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 47, 336–343.

- Tai, Y.C.; Lin, C.H. An overview of pain in Parkinson’s disease. Clin. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2020, 2, 1–8.

- Valkovic, P.; Minar, M.; Singliarova, H.; Harsany, J.; Hanakova, M.; Martinkova, J.; Benetin, J. Pain in Parkinson’s disease: A cross-sectional study of its prevalence, types, and relationship to depression and quality of life. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136541.

- Beiske, A.G.; Loge, J.H.; Rønningen, A.; Svensson, E. Pain in Parkinson’s disease: Prevalence and characteristics. Pain 2009, 141, 173–177.

- Buhidma, Y.; Rukavina, K.; Chaudhuri, K.R.; Duty, S. Potential of animal models for advancing the understanding and treatment of pain in Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Parkinson’s Dis. 2020, 6, 1.

- Rana, A.Q.; Qureshi, D.; Sabeh, W.; Mosabbir, A.; Rahman, E.; Sarfraz, Z.; Rana, R. Pharmacological therapies for pain in Parkinson’s disease—A review paper. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2017, 17, 1209–1219.

- Bruno, V.; Freitas, M.E.; Mancini, D.; Lui, J.P.; Miyasaki, J.; Fox, S.H. Botulinum toxin type A for pain in advanced Parkinson’s disease. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2018, 45, 23–29.

- Rieu, I.; Degos, B.; Castelnovo, G.; Vial, C.; Durand, E.; Pereira, B.; Durif, F. Incobotulinum toxin A in Parkinson’s disease with foot dystonia: A double blind randomized trial. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2018, 46, 9–15.

- Buhmann, C.; Kassubek, J.; Jost, W.H. Management of pain in Parkinson’s disease. J. Parkinson’s Dis. 2020, 10, S37–S48.

- Safarpour, Y.; Jabbari, B. Botulinum toxin treatment of movement disorders. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 2018, 20, 4.

- Rana, A.Q.; Kabir, A.; Dogu, O.; Patel, A.; Khondker, S. Prevalence of blepharospasm and apraxia of eyelid opening in patients with parkinsonism, cervical dystonia and essential tremor. Eur. Neurol. 2012, 68, 318–321.

- Hallett, M.; Evinger, C.; Jankovic, J.; Stacy, M. BEBRF International Workshop. Update on blepharospasm: Report from the BEBRF International Workshop. Neurology 2008, 71, 1275–1282.

- Savitt, J.; Aouchiche, R. Management of visual dysfunction in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J. Parkinson’s Dis. 2020, 10, S49–S56.

- Green, K.E.; Rastall, D.; Eggenberger, E. Treatment of blepharospasm/hemifacial spasm. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 2017, 19, 41.