Parkinson’s disease is the most common age-related motoric neurodegenerative disease. In addition to the cardinal motor symptoms of tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural instability, there are numerous non-motor symptoms as well. Among the non-motor symptoms, autonomic nervous system dysfunction is common. Autonomic symptoms associated with Parkinson’s disease include sialorrhea, hyperhidrosis, gastrointestinal dysfunction, and urinary dysfunction. Botulinum neurotoxin has been shown to potentially improve these autonomic symptoms.

- autonomic

- botulinum neurotoxin

- botulinum toxin

- non-motor

- Parkinson’s disease

1. Introduction

First described in 1817 by James Parkinson in his work “An Essay on the Shaking Palsy” [1], Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the most common age-related motoric neurodegenerative disease [2,3,4]. Estimates indicate that in 2010 the prevalence of PD in those over age 45 was 680,000 in the United States, with that number estimated to rise to 1,238,000 in 2030 [5]. The four cardinal features of PD are resting tremor, rigidity (i.e., increased resistance throughout the range of passive limb movement), bradykinesia (i.e., slowness of movement), and postural instability [6,7,8]. The non-motor aspects of PD include a variety of domains such as sleep disorders, pain, cognitive dysfunction, and autonomic dysfunction (i.e., dysautonomia) [2,7,9].

Idiopathic PD has traditionally been considered the most common form of parkinsonism [7,10,11]. More recently, however, the concept of idiopathic PD as a single entity has been challenged [7,8,12]. As we learn more about clinical subtypes, pathogenic genes, and possible causative environmental agents of PD, it seems logical that PD is more diagnostically complex than initially thought [7,12,13].

Pathologically, PD is associated with Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites consisting of misfolded and aggregated alpha-synuclein protein [7,14,15]. Physiologically, PD results in loss of dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta and subsequent basal ganglia dysfunction [4,15], as well as reduction in mitochondrial activity [4,7,16]. In addition, it has been found that disruption of non-dopaminergic pathways (e.g., noradrenergic, glutamatergic, serotonergic, and adenosine pathways) also occurs in PD and may account for the various non-motor symptoms [7,17].

Carbidopa-levodopa is considered the gold standard treatment for PD and mainly acts by replenishing dopamine in the nigrostriatal pathway [2,7,18]. Carbidopa-levodopa improves motor symptoms to a variable extent but does not substantially affect non-motor aspects of the disease [7,19,20]. With prolonged use, patients become less responsive to dopaminergic agents and experience a narrowing therapeutic window with side effects such as motor fluctuations, dyskinesias, autonomic nervous system dysfunction, and various neuropsychiatric symptoms [7,18,21]. Alternative therapies for PD include dopamine agonists, anticholinergics, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), catechol-O-methyl transferase inhibitors (COMTIs), deep brain stimulation, focused ultrasound lesioning, and botulinum neurotoxins [2,7,8,22].

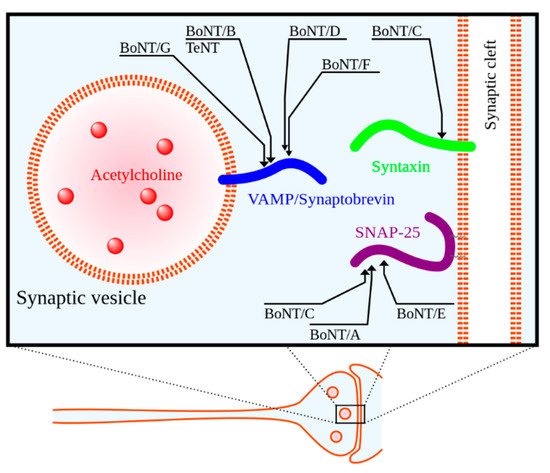

Botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT), regarded as the most potent toxin known to mankind, is produced by the anaerobic spore-forming Gram-positive bacillus Clostridium botulinum [23,24,25]. BoNT is a zinc protease that cleaves neuronal vesicle-associated proteins responsible for acetylcholine release into the neuromuscular junction [23]. See Figure 1 for a depiction of the mechanism of action. BoNT was first approved for medical use in Canada in the late 1980s for the treatment of strabismus (i.e., eye misalignment) [23]. FDA approval for clinical use of BoNT in the United States for strabismus and blepharospasm was subsequently granted in 1989 [23]. Since that time, the indications and use of BoNT have expanded.

There are seven biological serotypes of BoNT, with two of these serotypes used in clinical practice [24,25]. BoNT serotypes A and B, of which there are four formulations currently on the market, are used for a variety of medical indications including glabellar lines (i.e., facial wrinkles), dystonia (a disorder of involuntary muscle contractions causing repetitive or twisting movements), spasticity, and migraines [24,25,27,28]. See Table 1 for a summary of the four BoNT formulations currently available.

Table 1. Summary of botulinum neurotoxin formulations currently available for clinical use. Adapted from a review by Shukla and Malaty [27].

|

Toxin Property |

OnabotulinumtoxinA |

AbobotulinumtoxinA |

RimabotulinumtoxinB |

IncobotulinmtoxinA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Year introduced |

1989 |

1991 |

2000 |

2005 |

|

Trade name |

BOTOX® |

Dysport® |

Myobloc/NeuroBloc® |

Xeomin® |

|

Mechanism of action |

Cleaves SNAP 25 |

Cleaves SNAP 25 |

Cleaves VAMP |

Cleaves SNAP 25 |

|

Molecular weight (kD) |

900 |

500–900 |

700 |

150 |

|

Total protein (ng/vial) |

~5 |

~5 |

~50 |

~0.6 |

|

Units/vial |

50, 100, or 200 |

300 or 500 |

2500, 5000, or 10,000 |

50 or 100 |

|

Shelf life (months) |

36 |

24 |

24 |

36 |

|

Formulation |

Vacuum dried |

Freeze dried |

Sterile solution |

Freeze dried |

|

pH after reconstitution |

7.4 |

7.4 |

5.6 |

7.4 |

|

FDA-approved uses (in adults unless indicated) |

Cervical dystonia (16 years and up), blepharospasm (12 years and up), hyperactive bladder, upper and lower limb spasticity, strabismus (12 years and up), glabellar lines, axillary hyperhidrosis, and chronic migraine |

Cervical dystonia, glabellar lines, upper limb spasticity, and lower limb spasticity (2 years and up) |

Cervical dystonia and chronic sialorrhea |

Cervical dystonia, chronic sialorrhea, blepharospasm, and upper limb spasticity (2 years and up) |

|

Off-label uses |

Sialorrhea, hemifacialspasm, focal limb dystonia, oromandibular dystonia, tremors, tics, and tardive dyskinesia |

Sialorrhea, focal limb dystonia, oromandibular dystonia, and tremors |

Focal limb dystonia and oromandibular dystonia |

Focal limb dystonia and oromandibular dystonia |

Abbreviations: FDA = Food and Drug Administration, SNAP 25 = synaptosomal-associated protein 25, VAMP = vesicle associated membrane protein.

2. Discussion

2.1. Botulinum Neurotoxin for Sialorrhea

2.2. Botulinum Neurotoxin for Hyperhidrosis

2.3. Botulinum Neurotoxin for Gastrointestinal Dysfunction

2.4. Botulinum Neurotoxin for Urinary Dysfunction

2.5. Botulinum Neurotoxin for Pain

2.6. Botulinum Neurotoxin for Other Indications

It is worth noting that BoNT may be useful for the motor aspects of PD as well [24,25,27,56]. BoNT is increasingly being used for additional PD-related indications including blepharospasm (i.e., involuntary eyelid closure), oromandibular dystonia, cervical dystonia, limb dystonia, and tremors [27,56]. Although more common in atypical parkinsonism, blepharospasm can be seen in patients with idiopathic PD [72,73]. BoNT injection of the orbicularis oculi is effective and represents the first-line therapy for blepharospasm [60,74].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/toxins13030226