1. Introduction

Global climate change, along with local disturbances, are enhancing habitat degradation and biodiversity loss at an alarming rate and extension that is comparable only with past mass-extinction events [1]. Historically, restoration science has played a crucial role in the recovery of ecosystem properties and functions. However, with the current acceleration of environmental degradation, traditional restoration practices may no longer be sufficient [2][3]. Ecological restoration has become a major focus of conservation and natural resource management, as well as a strategy that can potentially provide realistic, context-specific pathways to a sustainable future. A meta-analysis estimated that global restoration practices had increased the provision of biodiversity and ecosystem services by an average of 25%–44% of what had been degraded [4], and some ecosystem services did recover with the success of restoration activities [5]. However, the restoration of marine ecological systems (including seagrasses) is still underdeveloped compared to terrestrial environments [6]. Although progress in restoration has been achieved for important marine ecosystems such as coral reefs, kelp forests, and seagrasses [7][8][9][10], the genetic research required for a proper restoration plan is not always applied, remaining more as a theoretical assumption rather than a practical action. In addition, legal issues on how to manage the genetic component of restoration are unclear [3][11].

Seagrasses are marine flowering plants that form extensive meadows in temperate and tropical waters of all continents except for Antarctica [12]. These meadows provide key ecological functions and ecosystem services to coastal areas and human livelihoods [13][14], ranking among the most valuable ecosystems on Earth along with coral reefs and tropical rainforests [15]. Seagrasses reproduce both clonally and sexually, these two strategies being dependent on external environmental conditions and internal cues [16][17][18][19]. Sexual reproduction ensures the rise of new genetic variants and boosts the plastic response of genotypes and populations to environmental changes [20]. Nevertheless, clonal (vegetative) propagation also plays a crucial role in the existence of seagrass species, contributing to important advantages, such as the colonization of vast areas and resource/risk sharing under unfavorable conditions [21][22][23][24]. In some species, sexual reproduction infrequently occurs, thus negatively affecting genetic diversity distribution within and among populations [25][26][27].

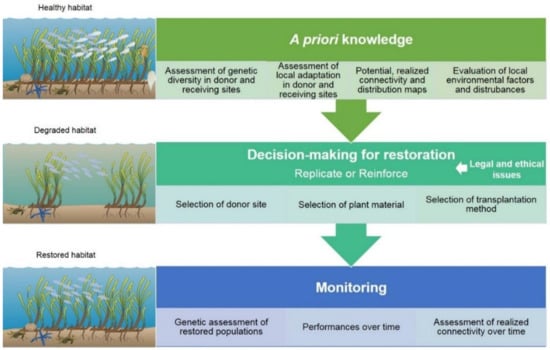

The decline of seagrass meadows reported in several regions of the world following extreme climate events (e.g., marine heatwaves and/or storms) is expected to occur more frequently in the coming decades [28][29]. It has been estimated that at least 1.5% of seagrass meadows are lost every year, and nearly 29% of their areal extent has disappeared since 1879 [30]. On the IUCN’s Red List (International Union for Conservation of Nature), 24% of seagrass species have been classified as either ‘threatened’ or ‘near-threatened’ [31]. The concurrent action of local and global stressors is impacting seagrass performances [32][33], consequently affecting associated organisms and communities [34] as well as goods and services provided by them [13]. In the light of accelerated decline, restoration has become a priority strategy to slow-down seagrass degradation and to repopulate degraded meadows, thus protecting and ultimately recovering their ecosystem functions and services [5][8]. The survival of restored populations will strongly depend on future climatic events, which could jeopardize the heavy investment in time and money associated with restoration programs. This situation is currently opening a debate of whether to restore coastal vegetation-based ecosystems to historical baselines or to use a restoration to facilitate adaptation to climatic scenarios expected in the future [35][36][37]. To increase their effectiveness, seagrass restoration efforts should improve predictive models combining environmental and genomic data (Figure 1) to have a reliable guideline for helping decision-making in the development of restoration plans [38].

Figure 1. Diagram showing different aspects of seagrass restoration. The restoration plan should include different steps. The “a priori” knowledge includes the assessment of genetic diversity and local adaptation in donor and receiving sites. Moreover, maps of potential and realized connectivity and the evaluation of local environmental status over the whole distribution area of the species are necessary to have a comprehensive baseline to perform a successful restoration plan and to select suitable donor sites. The restoration itself can be aimed to either replicate or reinforce genotypes in target sites and can be performed with different plant material and thorough different restoration methods (always according to the evaluation of legal and ethical issues). In order to assess the restoration success, genetic traits (diversity and connectivity) and performances (physiological, demographic, and growth traits) of newly established meadows must be monitored over time. Symbols were taken from courtesy of the Integration and Application Network, university of Maryland center for environmental science (http://ian.umces.edu/symbols/ accessed on 10 March 2021).

As we are approaching a new decade of ecosystem restoration [39], the need to rebuild marine life for a sustainable future has become more urgent than ever before [8]. Here, we aimed to provide a comprehensive review about genetic issues to be considered to perform a successful re-establishment of populations and for recovering lost ecosystem functions. To this end, we first reviewed conceptual frameworks related to genetic components in restoration, with a particular emphasis on seagrasses. We then discussed different genetic-related aspects to be considered for restoring degraded environments, including the choice of whether replicate or reinforce the extant genetic structure, the importance of having genetic diversity and connectivity maps, the selection of donor sites as well as the monitoring efforts after transplantation. We also investigated the actual situation of legal and ethical issues dealing with seagrass restoration at a regional, national and international scale. Finally, we discussed novel approaches and future directions for seagrasses genetic research that could improve the success of restoration activities.

2. A Brief Glance at Factors Shaping Genetic Diversity and Population Structure in Seagrasses

Genetic diversity is the basis for all biological diversity, which affects evolutionary and ecological processes at population, community, and ecosystem levels. It can be assessed in different ways and encompasses traits such as allelic richness (i.e., the average number of alleles per locus), heterozygosity (i.e., the average proportion of loci that carry two different alleles at a single locus within an individual), or genotypic richness (i.e., the number of genotypes within a population) [40]. Different methods used to quantify genetic diversity are explained in Box 1. Below, we briefly summarize the main factors shaping genetic variability and differentiation of seagrass populations, which should be taken into consideration for restoration purposes and should be a target for future research efforts.

2.1. Reproductive Strategies, Mutations

The level of genetic diversity in seagrass populations results from the balance between their sexual reproduction and clonal propagation, which in turn is related to different factors, including environmental conditions, dispersal abilities, and population connectivity [17][41][42]. Most seagrasses are dioecious [43] and therefore are outcrossed, while other species, such as Posidoniaceae and several Zosteraceae, are monoecious [44][45] with highly variable outcrossing rates [46][47][48][49]. As a result, seagrass meadows can range from almost monoclonal, with very low genetic and genotypic diversity [21], to extremely diverse [41]. Clonal growth has been recognized as a winner strategy in seagrasses, avoiding the potential accumulation of deleterious mutations and maintaining the most suitable genotype over time [50]. An important source of genetic variation in marine clonal plants is represented by somatic DNA mutations resulting in genetic mosaicism [51]. In clonal plants, genetic mosaics can occur at different levels of the ramet (i.e., the morphological individual [52]) organization, including (1) within the same module; (2) within connected modules; (3) between different modules that belong to the same clone. Recently, it has been demonstrated that the mosaic genetic variation in a large seagrass clone of Zostera marina was greater within than among ramets, pointing out the importance that somatic mutations have in structuring genetically unique modules [53].

2.2. Level of Genetic Connectivity, Population Size, and Genetic Drift

For species with a wide distribution range, different factors can contribute to population isolation [54]. Moreover, despite the apparent spatial uniformity of the sea, marine habitats are characterized by clear discontinuities, and the presence of dispersal barriers may create a genetic breakdown in marine populations due to local selective pressures [55]. Nevertheless, dispersal vehicles such as buoyant fruits and vegetative propagules can travel long-distance transported by marine currents (potential connectivity), and new genotypes or allelic variants can establish in disjoint populations (realized connectivity [56][57][58]). This implies that even if sexual reproduction occurs at a low rate, passive transport of sexual propagules can play an important role in maintaining population connectivity and in the colonization of new habitats [59]. Isolated and small populations are more prone to undergo genetic drift and bottleneck events, increasing allele loss and the possibility of fixation for deleterious alleles compromising their persistence in the future [49][60]. This is even more relevant considering the fragmentation of populations resulting from the current destruction of natural habitats [61]. These processes may thus lead to genetic erosion, reducing the fitness of individuals and increasing the chance populations can disappear [62].

2.3. Phenotypic Plasticity and Local Adaptation

Different populations of the same species distributed over environmental and geographic gradients can be locally adapted, depending on selection and patterns of gene flow. Local adaptation occurs when individuals have higher average fitness in their local environment compared to individuals from elsewhere [63]. The measurement of adaptive genetic diversity is more difficult than neutral genetic diversity and requires an accurate analysis of genotype-by-environment interactions [20]. Disentangling plasticity from environmentally driven adaptation requires experimental approaches such as reciprocal transplants and common garden experiments [20][64][65][66] that have been performed in few seagrass species. Experiments carried out on Z. marina and Posidonia oceanica populations from divergent climatic regions highlighted a high divergence in their phenotypes in response to environmental stressors (e.g., heat stress [67][68][69]). Within populations, variations in acclimation to warming were observed among P. oceanica individuals collected along a depth cline [70], while a reciprocal transplant in a common garden [71] of plants coming from different depths (i.e., contrasting light-environment) showed clear indications of local adaptation. Thus, a deep knowledge of eco-physiology of plants at the donor and target sites is also required to perform restoration programs. Although genetic linkage mapping [72] is not applicable for most seagrass species, due to the scarcity of genomic resources, a genetic-environment association analysis, using a genome scan approach and a genome-wide transcriptome analysis, started to identify genetic loci and functions potentially associate with the selective environmental factors along either a latitudinal and a bathymetric gradient [73]. Collectively, these studies suggest that local adaptation might play a role in shaping the divergence of seagrasses across environmental clines, even if it is not yet possible to assess how much of the observed phenotypic differences are heritable.

2.4. Disturbances

High genotypic diversity has been demonstrated to enhance the resistance and resilience of seagrasses to physical disturbances [17][74][75][76] or other stressful conditions such as heat stress or shading [76][77][78]. The level of genetic diversity of seagrass populations has also been shown to correlate with species richness and productivity [79][80] and ultimately with the associated community structure [79]. A high disturbance level can affect genetic diversity, leading to a decline in allelic or genotypic diversity or even to complete population extinction. Intermediate level of disturbance, instead, can boost sexual reproduction, increasing both allelic and genotypic diversity [17]. In general, the relationship between disturbance and genetic diversity is not simple, and the reciprocal causality of the two phenomena renders it difficult to assess the relative contribution of disturbance strength and frequency in relation to its effects on genetic components of diversity [17][40].

3. Integration of Genetic Research into Seagrass Restoration

How should a restored meadow be in order for it to successfully perform and persist? It should be genetically diverse and composed of genotypes locally adapted or able to adapt to the local environmental conditions. It should be connected, through a sufficient level of gene flow, with surrounding populations, in order to avoid negative effects of inbreeding depression, but it should not disrupt the local gene pool. It should be established to limit the damage to existing populations in providing source material and should comply with ethical and legal issues. Here we present and comment on key aspects to consider for a correct restoration plan.

3.1. Selection of Donor Sites

Genetic diversity is at the base of phenotypic diversity, which determines how restored populations will perform and respond to environmental stimuli at restored sites [74][75][81]. Prior to any restoration project, an accurate understanding of local environmental conditions and potential disturbances, the genetic makeup of populations nearby the transplantation site, and policies and legislation guidelines should be acquired in order to select proper donor sites. Many studies have investigated the relationship between genetic diversity (of both source and transplanted meadows) and the success of seagrass restoration plans (see Table 1). Those studies indicate that the selection of donor sites displaying a high level of genetic diversity as well as the choice of plant materials (e.g., adult plants, seeds, or seedlings) is crucial for maximizing restoration success.

Table 1. List of the most relevant studies investigating the effects of genetic diversity on seagrass restoration plans. Data were collected from Google Scholar using “seagrass restoration” plus “seagrass genetic” as keywords together with personal knowledge from the authors. Year: year when transplantation started; *: multiple restorations; related ref: see related reference for more details.

| Species | Year | Donor Location | Restored Location | Plant Material | Area | Duration | Genetic Diversity Assessment | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Posidonia australis | 2013 | Jervis Bay (Australia) reciprocal transplant study | St. Georges Basin (Australia) reciprocal transplant study | Adult plants | na | 6 months | Eight microsatellites | [11] |

| Zostera noltei | 2009 | Carteau in the Gulf of Fos (France) | Berre lagoon (France) | Adult plants | 450 m2 | 4 years | Nine microsatellites | [82] |

| Zostera marina | 2007 | Mobjack Bay, Chesapeake Bay, South Bay, USA | Hog Island Bay, USA | Seeds | 128 m2 | 20 months | Eight microsatellites | [83] |

| Zostera marina | 2006–2007 * | Chesapeake Bay (USA) | Virginia coastal bays (USA) | Seeds | na | 2–3 years | Eight microsatellites | [84] |

| Posidonia australis | 2004 | Parmelia Bank, Cockburn Sound (Australia) | Southern Flats, Cockburn Sound (Australia) | Adult plants | 3.2 ha | 4 years | Seven microsatellites | [85] |

| Zostera marina | 2001–2008 * | Related ref | related ref | Adult plants | related ref | 10 years | Seven microsatellites | [86] |

| Zostera marina | 2000 | Two sites along the German Baltic Coast | Two sites along the German Baltic Coast | Adult plants | 450 m2 | 11 weeks | Four microsatellites | [87] |

| Zostera marina | Late 1990s | Chesapeake Bay | Twenty-three meadows along the eastern coast of North America | Seeds | 1600 ha | 15 years | Seven microsatellites | [88] |

| Posidonia oceanica | 1994 | Gorgona Island, Pantelleria Island (Italy) | Vada (Italy) | Adult plants | na | 3 years | Six microsatellites | [89] |

| Halodule wrightii | 1993–2000 * | Related ref | Related ref | Adult plants | na | 2–7 years | 98 AFLPs | [90] |

| Zostera marina | 1993 | South San Diego Bay (USA) | North San Diego Bay (USA) | Adult plants | na | 2 years | Allozyme electrophoresis | [81] |

| Zostera marina | related ref * | Related ref | Related ref | Adult plants | Related ref | 3–16 years | Allozyme electrophoresis | [91] |

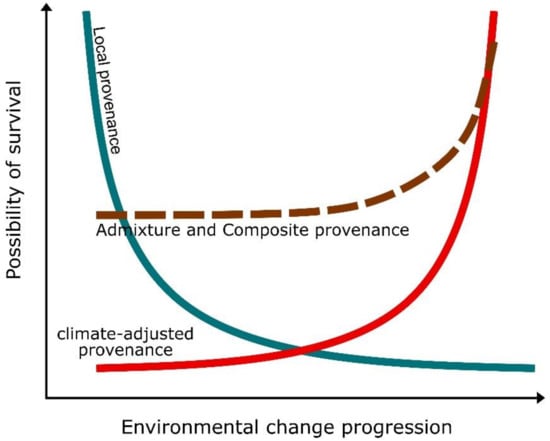

To date, the most widely applied approach of restoring a former local gene pool is by sourcing the plant material from nearby or well-connected donor sites, i.e., local provenance (Figure 2). The reason is that locally adapted plants are believed to fit the condition of the site being restored. However, trying to replicate what is already lost is inappropriate in highly degraded environments, and better environmental conditions should be achieved first.

Figure 2. Graph showing the conceptual relationship between local (blue line), climate-adjusted (red line), admixture and composite (dashed line) provenance (sensu Prober et al. [92]) with the possibility of survival of the restored seagrasses under environmental change (e.g., ocean warming, eutrophication, etc.).

Native genotypes that have already suffered past environmental disturbances could also be unable to overcome the recurrence of such perturbation or new stressful conditions in the future [36]. Sgrò et al. [93] identified critical problems of this “local is best” practice, including (1) the risk of establishing populations that do not exhibit sufficient genetic variation and evolutionary potential; (2) the possibility that particular environmental conditions driving local adaptation can change very quickly, hampering the advantage of using locally adapted genotypes. This is particularly important and can cause serious impacts on restoration outcomes, considering the speed at which environmental changes are occurring. On the other hand, the introduction of novel genotypes from distant sources (assisted gene flow) has the potential to restore levels of genetic diversity (genetic restoration), increasing the overall fitness of inbreeding-depressed populations (genetic rescue). Nevertheless, it may also result in deleterious effects as a consequence of outbreeding depression and maladaptation [94][95]. According to a modeling approach by Aitken and Whitlock [96], the risks and consequences of outbreeding depression and contamination of the local gene pool are minor in respect to potential advantages.

Another important aspect to consider in the selection of donor sites is the taxonomic uncertainty, which characterizes some seagrass groups, such as, for example, the Halophila genus [97][98]. The high morphological plasticity of species and the presence of locally adapted morphotypes could lead to erroneous species identification. This could favor in turn, the hybridization with native species, the breakdown of locally adapted ecotypes, and the establishment of hybrids (i.e., genetic swamping), potentially compromising the entire ecosystem functioning [99]. In this case, species identification should also be performed at a genetic level to overcome taxonomic ambiguity.

In order to utilize donor material potentially able to respond to projected climate changes, source populations can be selected within the distribution range of the species in areas experiencing environmental conditions as projected in the near future for the transplantation site, i.e., climate-adjusted provenance (Figure 2, red line) [88]. This source material could be utilized together with material coming from healthy local populations or from multiple sources across the species range, i.e., a composite and admixture provenance (Figure 2, dashed line) [92]. The latter is especially suitable for most seagrass species, where information about genotypic plasticity and potential response to changes is scarce. Furthermore, many seagrass species exhibit wide latitudinal ranges of distribution [100], making the selection of climate-adjusted or admixture provenance easier. These strategies may not result in a high survival rate of restored populations in the short-term as they can experience intraspecific hybridization with local and non-local genotypes (i.e., outbreeding depression) or maladaptation [94][95][101]. However, in the long-term, the introduction of “future climate-adapted” genotypes can enhance the survival and longevity of the restored meadows [6][10][92]. Even holding great potentials for seagrass restoration, there are still limitations in choosing non-local donor material approaches that require further investigation. For instance, to apply admixture provenance, it is important to establish the right proportion of local and climate-adjusted plant material and the number of donor populations to select. Sometimes, this is also highly dependent on the availability of material at both source and receiving sites (see Section 3.2).

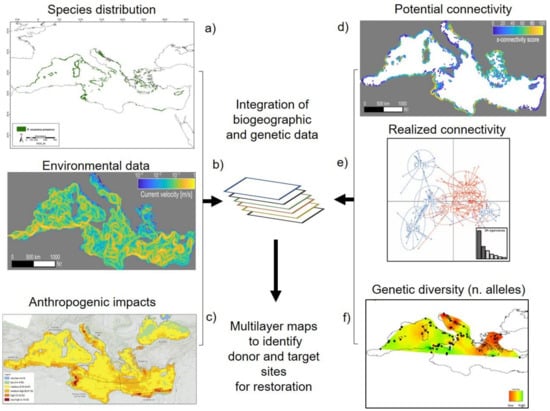

3.2. Integration of Biogeographic and Genetic Data

Integrating genetic diversity information with biogeographical and oceanographic data into connectivity maps can be very helpful in the selection of donor sites and the monitoring of restoration efforts (Figure 3). This becomes particularly useful for species with the potential to disperse over long distances via ocean currents during various life stages [59][102] and for species with a highly variable level of meadow genetic diversity over their distribution range (e.g., P. oceanica [103][104]). These maps, together with habitat suitability and site selection models [105], are important to identify whether or not seagrass recovery can naturally occur or whether the targeted population would remain isolated after being restored (in this case, restoration is not advisable). In the first case, it is the result of a high level of connectivity and gene flow between degraded and neighboring sites, or in the second case, resulting from the absence of population connectivity. In the last case, the integration of genetic diversity, connectivity, and environmental data could reveal the reasons behind the isolation of the target area and the possible way of restoring dispersal and connectivity networks ([106]). Recently, Mari and colleagues [58] built maps of potential connectivity for P. oceanica, modeling the dispersal and potential exchange of propagules between sites evaluating environmental features. The resulting patterns could be integrated with genetic data of target populations useful for choosing potential donor populations. Survival data from seagrass restoration can also be used to investigate fundamental niches and model the persistence potential of restored seagrass meadows [107][108]. Recently, Oreska et al. [109] analyzed the presence and absence data of seedlings from restored plots in the Virginia Coast Reserve through Species Distribution Models (SDMs) to identify potential environmental factors that affect the survival rate of different sites. This offered the opportunity to compare the extent of the realized and fundamental niche of the restored and natural sites, improving management efforts to accelerate seagrass coverage and recovery.

Figure 3. Examples of models and distributions maps and genetic data from seagrass’ studies of the Mediterranean Sea. The integration of species distribution (a [110]), environmental data (b [58]), anthropogenic impacts (c [111]), with potential (d [58]) and realized connectivity maps (e [57]) and genetic diversity analysis (f [112]) could be combined to develop multilayers maps for the identifications of donor and target sites in seagrass restoration (see text for more detail). The figure was modified from the studies cited above.

The integration of information from genetic diversity into connectivity maps may also help to keep track of historical gene flow and local adaptation while at the same time, avoid the loss of genetic variation at the restored sites [113]. Seagrass genetic diversity tends to decrease in populations that locate at the range-edge of the species’ distribution range [49][102]. This phenomenon has been suggested as the result of reduced seed production and pollen limitation [10][49] and limited connectivity of populations [114][115][116]. Range-edge populations often exhibit smaller effective population sizes, making them unsuited as donor sites [114][115][117]. Indeed, many studies have recommended that populations with large effective population sizes are the most appropriate donor sites [117]. These populations actually possess the genetic potential to better adapt to more extreme environmental conditions (e.g., marine heatwaves) and could be used as potential restoration materials for the future as ocean warming continues to rise [10][114]. However, these populations could also be at high risk of extinction if the speed of environmental change overrides their capacity to adapt [118].

Distribution and connectivity maps together with a priori knowledge of population structure should be integrated with the reproductive characteristics of related seagrass meadows [114][119]. For example, after studying reproductive and genetic profiles of P. australis meadows across Western Australia, Sinclair et al. [114] showed flower and fruit production variability between northern range-edge meadows and center range ones, with the first showing mixed mating system and lower sexual productivity. This evidence suggests that future restoration activities may benefit from sourcing plant material from multiple reproductive meadows. Future efforts on making complete maps (or georeferenced databases) as guidelines to restoration should also include information regarding intraspecific differences in genetic diversity, e.g., among different depths of the same population as seen in the case of the seagrass Z. marina [118] and P. oceanica [120][121], which can have potential implications in the collection of plant material.

3.3. Selection of the Plant Material

Different species of seagrasses have different morphological and reproductive traits, affecting in a different way restoration success. Moreover, restoration plans have mainly focused on species with higher ecosystem value (providing more valuable ecosystem services) and also forming monospecific meadows. Only one-third of the extant seagrass species have been utilized in restoration programs, with Z. marina present in more than 50% of the trials [122]. Other species highly utilized in restoration plans are the ones from the Posidonia genus in the Mediterranean and in Australia. Most of the restoration plans occur in temperate areas of the United States, Europe, Australia, and Eastern Asia [122].

Seagrass restoration can be performed by using different parts of the plant, such as rhizome fragments, seedlings, or seeds [122]. The most common approach implies the collection of adult plants with well-developed shoots and roots [85][122]. However, adult plant-based methods are often labor-intensive and costly, as the survival rate of transplanted shoots is strongly related to the amount of planted material used [10]. In contrast, the use of seed-based methods instead of adult shoots, particularly in large restoration plans, can result in a much lower impact on existing meadows (i.e., donor sites) [10]. Moreover, seed-based transplantation approaches are less expensive and more logistically feasible when restoring larger areas [88][123]. As reported by van Katwijk et al. [122], large-scale restoration trials (> 100,000 shoots/seeds planted) perform better than small trials, and part of these results depend on the initial sourcing material, which should have high genetic and genotypic diversity. One of the best examples of large-scale restoration in seagrasses was performed along the mid-western Atlantic coast, where over 70 million Z. marina seeds were planted from 1999 to 2010 [124]. In this case, the collection of a large number of seeds from multiple parents did offset potential genetic bottlenecks ensuring high genetic diversity of donor plants and thus of restored sites [84]. Orth et al. [125] also demonstrated that a large restoration plan not only restored local seagrass coverage but also improved water quality and ecosystem functioning, supporting other restoration programs (e.g., scallops). Seed-based methods can quickly facilitate the recovery of populations with higher genetic diversity [83][90] and have the advantage of maintaining genetic variation mimicking natural ecological and evolutionary processes [93][123]. Thus, it is considered as a valid approach to restore and redefine populations that are more capable of persisting to changing environmental conditions. However, it is still unclear if and how massive seed collection can impact the survival and genetic composition of donor populations in the long-term. Although the acquisition and processing of large amounts of seeds is a limiting factor in most seagrass species, other species, such as Z. marina, produce large quantities of seeds that are released in a short time, allowing the implementation of different approaches to store and maintain collected seeds viable [126].

Nevertheless, seed-based methods still have limitations that deserve further efforts from the scientific community. For example, more information is needed about sexual reproduction and other biological characteristics of plants, such as flowering time, seed production strategies, dormancy, and germination condition. Furthermore, it has been found that in P. australis new seedlings have a low initial establishment rate, which depends on local environmental conditions [127], while in Z. marina in natural conditions, only around 5%–10% of seeds can survive and germinate [128].

3.4. Genetic Assessment of Transplantation Success

The success of seagrass restoration has historically been evaluated by demographic monitoring, which only informs about population processes such as recruitment, survival, and reproductive success, but that do not provide insights into the evolutionary resilience of restored populations or about the consequences of reproductive processes following restoration actions [129]. Genetic monitoring evaluates the success in restoring genetically viable populations and whether the positive effects of the restoration are maintained over time (i.e., across successive generations). Thus, well-designed monitoring programs are required, including also evaluation of changes in environmental conditions of the restored site and referring to comparable time frames for the same species [130]. Monitoring genetic changes in restored populations can be done retrospectively by using pre-disturbance genetic population datasets or for evaluating ongoing changes in their status and persistence (i.e., mid-and long-term restoration outcomes). Measuring changes in population allele frequencies or levels of linkage disequilibrium over time, using neutral markers, can provide information about absolute changes in the restored population (e.g., effective population size) and can be relevant for digging into the genetic processes driving these changes (e.g., selection, genetic recombination, mutation, genetic drift, mating system, and genetic linkage).

Genetic monitoring can also be useful to inform about the factors and processes underlying the success or failure of a restoration action, which could be critical to adjust management practices accordingly [131]. For instance, when mixed source populations are used in restoration, genetic monitoring has the potential to inform whether genotypes from different origins have been admixed or if the local genetic characteristics are maintained and not completely replaced by the newly introduced foreign genotypes. In the latter case, this would involve a reduction in the overall genetic diversity of the restored population, compromising its evolutionary potential in future environmental scenarios. In species with high clonal propagation, genetic monitoring could also inform whether the establishment of new recruits is the result of clonal spread or sexual reproduction, the latter being indicative of successful population rejuvenation [132].

Combining molecular markers with fitness-related phenotypic traits can provide a quantification of genetic variability and structure, as well as further valuable information about the progression of the restored population and the likely existence of constraints to recovery. For instance, genetic monitoring just several generations after the completion of a restoration action can reveal the existence of reduced fitness of inbred offspring (inbreeding depression; Z. marina [68]) or reduced fitness of progeny involving an admixture of different sources or of native and foreign genotypes (outbreeding depression; Z. noltei [133]). Additionally, monitoring the genetic structure of restored populations can identify the re-establishment of a gene flow between the restored and closely populations (e.g., Z. muelleri [134]) as well as factors that have the potential to alter the future population genetic structure (e.g., Z. marina [135]). Whether selection pressures in the restored habitat with mixed source populations have the potential to result in population differentiation in the long term can also be inferred. Since fitness of transplants may depend both on the source origin and the particular environmental conditions of the restored habitat, the higher fitness in critical traits (e.g., sexual reproduction) of locally adapted genotypes might result in within-population differentiation. This can also result from heterosis, as heterozygous individuals are relatively fitter than homozygous individuals [136].

In addition, genetic monitoring could also shed light on the genetic basis influencing the provision of ecosystem services [133], which is a major outcome pursued in restoration programs. Reynolds et al. [84] found that a small increase in genetic diversity in transplant plots of the seagrass Z. marina improved restoration success, but also the provision of valuable ecosystem services (i.e., habitat provision, primary productivity, and nutrient cycling). The authors argued that the mechanism behind this ecosystem services enhancement was the increase in shoot density promoted by high genetic diversity in transplant plots.

For all the above, monitoring of transplants is essential to identify timely evidence-based information that can ultimately enhance the long-term success rates of transplantation efforts by establishing additional actions and modifications (see Figure 1). This information can also uncover mechanisms limiting transplantation success to inform future projects [124]. As the recovery of seagrass meadows can take from two to over 30 years to reach a fully functional state [6], and negative impacts of improper donor sites (e.g., in genetic aspects) can also take decadal times to be detectable [101][137]. All these make long-term seagrass monitoring essential. Unfortunately, most agencies typically fund restoration projects over a short period (e.g., in Australia from one to 10 years [6]) that is usually not enough for appropriate monitoring. Besides the devoted efforts of the scientific community, restoration programs require the involvement and commitment of all stakeholders in the industry, local communities, citizen-science projects, non-governmental organizations, states, and federal government agencies to establish multi-year to decadal funded restoration projects in order to progressively improve seagrass restoration outcomes and to complete the ambitious restoration goals set out for the present decade.