| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SABELLE JALLOW | + 8813 word(s) | 8813 | 2021-03-08 07:29:40 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | -5088 word(s) | 3725 | 2021-03-19 02:24:09 | | |

Video Upload Options

Ibrexafungerp (formerly SCY-078 or MK-3118) is a first-in-class triterpenoid antifungal or “fungerp” that inhibits biosynthesis of β-(1,3)-D-glucan in the fungal cell wall, a mechanism of action similar to that of echinocandins. Distinguishing characteristics of ibrexafungerp include oral bioavailability, a favourable safety profile, few drug-drug interactions, good tissue penetration, increased activity at low pH and activity against multi-drug resistant isolates including C. auris and C. glabrata. In vitro data has demonstrated broad and potent activity against Candida and Aspergillus species. Importantly, ibrexafungerp also has potent activity against azole-resistant isolates, including biofilm-forming Candida spp., and echinocandin-resistant isolates. It also has activity against the asci form of Pneumocystis spp., and other pathogenic fungi including some non-Candida yeasts and non-Aspergillus moulds. In vivo data have shown IBX to be effective for treatment of candidiasis and aspergillosis. Ibrexafungerp is effective for the treatment of acute vulvovaginal candidiasis in completed phase 3 clinical trials.

1. Introduction

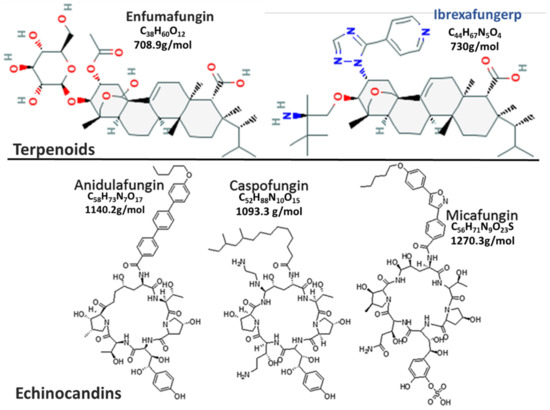

Antifungals that inhibit the biosynthesis of β-(1,3)-D-glucan, an important cell wall component of most fungi, the potential to exhibit potent broad-spectrum of activity [1][2]. These drugs target an enzyme, β-(1,3)-D-glucan synthase that is unique to lower eukaryotes, limiting their toxicity in humans [1][3]. The echinocandins were the first glucan synthase inhibitors approved for use in 2001 [4] and have broad-spectrum activity against most common fungal pathogens (Candida spp., Aspergillus spp.), except for Cryptococcus neoformans [5]. Despite their good efficacy in the treatment of invasive Candida infections and low toxicity, their use is limited to parenteral administration only [2][3]. Echinocandins have very high molecular masses of about 1200 kDa [2][6], possibly resulting in their poor oral absorption [3][7][8]. Furthermore, distribution of the first-generation echinocandins to the central nervous system, intraocular fluids, and urine is poor, mainly due to their high protein-binding capabilities (>99%) and high molecular masses [3][7][8]. Active research into new drugs by high throughput screening of natural products from endophytic fungi led to the discovery of enfumafungin, a triterpene glycoside [9]. Enfumafungin is structurally distinct from echinocandins (Figure 1) [10][11], forming a new class of antifungals called “fungerps” (Antifungal Triterpenoid) [12][13][14]. Modifications of enfumafungin for improved oral bioavailability and pharmacokinetic properties led to the development of the semi-synthetic derivative, which was named ibrexafungerp (IBX) [15] by the World Health Organization’s international non-proprietary name group [16].

Figure 1. This is a figure comparing Fungerp and Echinocandin chemical structures (modified from [10][11]).

2. Mechanism of Action and Resistance

Ibrexafungerp (formerly SCY-078 or MK-3118) is a first-in-class triterpenoid antifungal that inhibits biosynthesis of β-(1,3)-D-glucan in the fungal cell wall. Glucan represents 50–60% of the fungal cell wall dry weight [17]. β-(1,3)-D-glucan is the most important component of the fungal wall, as many structures are covalently linked to it [17]; furthermore, it is the most abundant molecule in many fungi (65–90%) [17][18], making it an important antifungal target [1][12]. Inhibition of β-(1,3)-D-glucan biosynthesis compromises the fungal cell wall by making it highly permeable, disrupting osmotic pressure, which can lead to cell lysis [19][20][21]. β-(1,3)-D-glucan synthase is a transmembrane glycosyltransferase enzyme complex comprised of a catalytic Fks1p subunit encoded by the homologous genes FKS1 and FKS2 [22] and a third gene, FKS3 [23]; a rho GTPase regulatory subunit encoded by the Rho1p gene [24]. The catalytic unit binds UDP-glucose and the regulatory subunit binds GTP to catalyse the polymerization of UDP-glucose to β-(1,3)-D-glucan [25], which is incorporated into the fungal cell wall, where it functions mainly to maintain the structural integrity of the cell wall [19][20][21].

Ibrexafungerp (IBX) has a similar mechanism of action to the echinocandins [26][27] and acts by non-competitively inhibiting the β-(1,3) D-glucan synthase enzyme [12][27]. As with echinocandins, IBX has a fungicidal effect on Candida spp. [28] and a fungistatic effect on Aspergillus spp. [29][30]. However, the ibrexafungerp and echinocandin-binding sites on the enzyme are not the same, but partially overlap resulting in very limited cross-resistance between echinocandin- and ibrexafungerp-resistant strains [26][27][31]. Resistance to echinocandins is due to mutations in the FKS genes, encoding for the catalytic site of the β-(1,3) D-glucan synthase enzyme complex; specifically, mutations in two areas designated as hot spots 1 and 2 [32][33], have been associated with reduced susceptibility to echinocandins [33][34]. The β-(1,3) D-glucan synthase enzyme complex is critical for fungal cell wall activity; alterations of the catalytic core are associated with a decrease in the enzymatic reaction rate, causing slower β-(1,3) D-glucan biosynthesis [35]. Widespread use and prolonged courses of echinocandins have led to echinocandin resistance in Candida spp., especially C. glabrata and C. auris [36][37][38][39][40]. Ibrexafungerp has potent activity against echinocandin-resistant (ER) C. glabrata with FKS mutations [41], although certain FKS mutants have increased IBX MIC values, leading to 1.6–16-fold decreases in IBX susceptibility, compared to the wild-type strains [31]. Deletion mutations in the FKS1 (F625del) and FKS2 genes (F659del) lead to 40-fold and >121-fold increases in the MIC50 for IBX, respectively [31]. Furthermore, two additional mutations, W715L and A1390D, outside the hotspot 2 region in the FKS2 gene, resulted in 29-fold and 20-fold increases in the MIC50 for IBX, respectively [31]. The majority of resistance mutations to IBX in C. glabrata are located in the FKS2 gene [31][40], consistent with the hypothesis that biosynthesis of β-(1,3) D-glucan in C. glabrata is mostly mediated through the FKS2 gene [32].

3. Important Pathogenic Fungi and Antifungal Spectrum

Invasive fungal infections (IFIs) are usually opportunistic [42]. The incidence of IFIs has been increasing globally due to a rise in immunocompromised populations, such as transplant recipients receiving immunosuppressive drugs; cancer patients on chemotherapy, people living with HIV/AIDS with low CD4 T-cell counts; patients undergoing major surgery and premature infants [42][43]. IFIs are a major cause of global mortality with approximately 1.5 million deaths per annum [44]; mainly due to Candida, Aspergillus, Pneumocystis, and Cryptococcus species [44]. Furthermore, there is an increase in antifungal resistance limiting available treatment options [45][46]; a shift in species causing invasive disease [47][48][49][50] to those that may be intrinsically resistant to some antifungals [51][52]. Several fungal pathogens (e.g., Candida auris, Histoplasma capsulatum, Cryptococcus spp., Emergomyces spp.) are gaining importance, especially in middle-income countries such as South Africa, India, Brazil and Colombia.

Candida auris has been reported in over 39 countries as an important emerging fungal pathogen [48] with a high crude mortality rate and a propensity for multidrug resistance [53][54][55][56][57][58][59]. C. auris has also been reported as an important cause of nosocomial outbreaks [60][61] due to its ability to colonize skin, form biofilms and resist standard disinfectants; due to its ease of person-to-person and person-to-environment transmission [60][61][62]. Within the last decade, C. auris became the third most common cause of candidaemia in South Africa, causing >10% of all culture-confirmed cases of invasive candidiasis [49][63][64]. A large proportion of C. auris infections are fatal due to the comorbidities in these patients, but multidrug- or even pan-resistance to available antifungals may also contribute to inappropriate treatment and adverse outcomes [53][54][55][56][57][58][59].

Invasive aspergillosis, a life-threatening acute disease, has a reported mortality of up to 85% [65][66]. First-line treatment is with voriconazole, though resistance to the azole class of drugs has been reported [67][68][69]. Resistance to amphotericin B formulations, used as alternative therapy, is rarer, although Aspergillus terreus is intrinsically amphotericin B-resistant [47].

Pneumocystis infections [70] have gained importance in the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) era as an acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-related opportunistic infection [70]. Pneumocystis jirovecii causes Pneumocystis pneumonia in humans (PCP), which is still a leading cause of opportunistic infection in HIV/AIDS patients, even in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy [71]. In addition, Pneumocystis infections are increasing in non HIV-infected populations with impaired cell–mediated immunity, including those on immunomodulatory drugs or with underlying medical conditions such as inflammatory or autoimmune diseases [72][73]. First-line treatment is usually with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) (alternatives include clindamycin-primaquine, atovaquone and pentamidine) [74] instead of the known antifungal classes. Pneumocystis jirovecii utilizes cholesterol, a mammalian-associated sterol, instead of ergosterol [75]; whose biosynthetic pathway is exploited by most antifungals, leading to intrinsic resistance of Pneumocystis spp. to these drugs [74]. Resistance mutations in the dihydropteroate synthase and cytochrome bc1 genes against TMP-SMX and atovaquone have already been identified [76]. Pneumocystis spp. are sensitive to glucan synthase inhibitors; however, owing to their unique life cycle, only the ascus (cyst) forms and not the trophic forms are sensitive to these drugs [74]. Glucan synthase inhibitors can therefore, only control, but not eradicate PCP colonization/infection [74].

The activity of glucan synthase inhibitors depends on the proportion of β-(1,3) D-glucan in the fungal cell wall, which can differ in different fungal species [77]. Most Saccharomyces, Candida and Aspergillus species, are susceptible to glucan synthase inhibitors [7][20][26][41][78][79][80], because β-(1,3) D-glucan is dominant in their cell walls [77]. These drugs also have activity against the ascus form of Pneumocystis jirovecii [81]. Fungi, such as those in the order Mucorales, Fusarium spp. and Scedosporium spp. with limited or no β-(1,3) D-glucan, are intrinsically resistant to this class of drugs [82]. However, a paradox occurs in Cryptococcus neoformans whose cell wall contains predominantly β-(1,3) D-glucan, yet is tolerant to this class of drugs [5][83].

4. In vitro activity

Yeasts: In vitro analysis of ibrexafungerp showed potent activity against a broad spectrum of >1300 Candida isolates [41][80][84][85][86][87][88][89][90][91]. Activity against C. lusitaniae and C. krusei (MIC range: 1–2 and 0.5–4 µg/mL, respectively), seemed to be less potent compared to other Candida spp. [87]. Compared to echinocandins, IBX was generally less potent (higher MIC values) for most common Candida spp., except for C. parapsilosis [86][87]. Ibrexafungerp showed strong activity against azole-resistant isolates (including C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, C. auris, C. krusei, C. glabrata, C. guilliermondii, C. lusitaniae, C. inconspicua) [84][87][90]; however, activity against echinocandin-resistant FKS mutants (C. albicans, C. krusei, C. tropicalis, C. glabrata, C. auris) was variable [84][86]. IBX has more activity against a majority of FKS mutants compared to the echinocandins, with 70–86% of echinocandin-resistant mutants susceptible to IBX compared to 17–50% for the echinocandins [80][84][86][87][88][89], possibly because selection of these mutants were due to echinocandin exposure. Most Candida echinocandin-resistant FKS mutants were susceptible to IBX [26][84][87][88], especially C. glabrata [41][87][89] and C. auris isolates [57][90], but some mutants with the F641S, F649del, F658del and F659del mutations had reduced susceptibility to IBX [80][84][86][89]. Ibrexafungerp produced enhanced activity against echinocandin-resistant C. albicans and C. glabrata, compared to caspofungin [80]. IBX also demonstrated potent activity against pan-resistant (resistance to ≥2 azoles, all echinocandins and amphotericin B) C. auris isolates from a New York City outbreak [57]. Candida biofilms use multiple resistance mechanism to escape from antifungals; leading to inherent resistance to azoles [92][93]. β-(1,3)-D-glucan is a key component of biofilm constituent; thus, it is not surprising that IBX has shown activity against different biofilm-producing Candida species (C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, C. glabrata) [41][84].

Among 13 other non-Candida yeasts including Rhodotorula mucilaginosa, Trichosporon spp. (T. asahii, T. dermatis, T. inkin, T. japonicum) and Arxula adeninivorans, IBX activity was variable ranging from 0.25–≥128 µg/mL [84]. In another study of 100 non-Candida yeasts, IBX showed activity against Malassezia pachydermatis (MIC: 0.5 μg/mL), Pichia spp. (MIC: 0.5–1 μg/mL) and to some Trichosporon mucoides (MIC range: 0.125–2 μg/mL) [94]. In vitro analysis of IBX, at different pH levels against Candida spp., showed increased potency at lower pH, with MIC90 values of 0.5, 0.25 and <0.016 μg/mL at pH levels of 7.0, 5.72 and 4.5, respectively; indicating increased activity at low pH (owing to its pH-dependent solubility) that may increase potency for treatment of vulvovaginitis [95].

Moulds: Glucan synthase inhibitors have a fungistatic effect on some moulds [29][30], such as Aspergillus spp., despite high proportion of β-(1,3) D-glucan in the Aspergillus cell wall [29]. While these drugs may not kill these species of mould, they can have a profound antifungal effect both in vitro and in vivo [29][30]. Treatment with glucan synthase inhibitors causes lysis of growing hyphal tips; leading to short, stubby, highly branched hyphae or abnormal hyphal growth [29][96]. The fungistatic effect of these drugs means that MIC values are not accurate endpoint measures; instead minimum effective concentrations (MEC) (the lowest concentration at which abnormal hyphal growth occurs) are usually used in antifungal susceptibility testing [96]. IBX showed potent in vitro inhibition of Aspergillus species complexes (A. fumigatus, A. niger, A. flavus, A. terreus, A. nidulans, A. glaucus, A. ustus, A. versicolor, A. westerdijkiae, A. tamarii, A. calidoustus), including azole-resistant strains [26][30][80][94]. Echinocandin-resistant (ER) Aspergillus spp. are very rare, although an A. fumigatus mutant (S678P) has been described [97]. IBX showed increased activity against the S678P ER mutant with a MIC value that was 133-fold less than that observed for caspofungin [26].

IBX activity against medically important non-Aspergillus moulds including the Order Mucorales (Rhizopus, Mucor, Rhizomucor, Cunninghamella, Lichtheimia species), Fusarium spp., Scedosporium spp., Paecilomyces spp., and Scopulariopsis spp. showed variable results [98]. IBX was very active against Paecilomyces variotii, Penicillium citrinum, Scytalidium dimidiatum, Alternaria spp. and Cladosporium spp.; but had limited to no activity against the Mucorales, Fusarium spp., Purpureocillium lilacinum, Lichtheimia coerulea, Lichtheimia corymbifera, Acremonium spp., Cladosporium cladosporioides, Trichoderma citrinoviride and Trichoderma longibrachiatum [94][98]. IBX showed variable activity against Scopulariopsis spp. and modest activity against Scedosporium apiospermum and Lomentospora (formerly Scedosporium) prolificans [98]. Interestingly, IBX was the only drug, amongst those tested, that had any activity against the pan-resistant Lomentospora prolificans isolates [98].

Other fungi: Among dermatophytes, IBX demonstrated potent activity against Microsporum canis, Trichophyton tonsurans, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, and Trichophyton rubrum [94].

5. In vivo data from animal models

In a neutropenic murine model of invasive candidiasis, ibrexafungerp administered orally every 12 h showed in vivo activity against both wild type (30 mg/kg) and echinocandin-resistant (40 mg/kg) C. glabrata strains, while caspofungin showed activity against the wild type strains only [99]. IBX given orally showed activity against C. albicans, C. glabrata, and C. parapsilosis in a neutropenic murine model of disseminated candidiasis, [100][101]. In an in vivo study of C. auris skin colonization in guinea pigs, 10 mg/kg oral dose of IBX produced a significantly lower fungal burden in the treated guinea pigs compared to those untreated; however with higher IBX doses (20 and 30 mg/kg) and with micafungin (5 mg/kg), the reduction in fungal burden was not significant [102]. At the end of treatment, histopathology results showed no fungal elements in all treated animals, while the untreated animals had fungal elements present, indicating that all treatment arms were able to clear the C. auris colonization [102]. Intra-abdominal candidiasis (IAC) is a difficult-to-treat invasive disease due to poor drug penetration at the site of infection and hence associated with high mortality [103][104]. In a mouse model of IAC, ibrexafungerp exhibited good penetration with robust accumulation within intra-abdominal lesions [103]. IBX concentrations in liver abscesses were 100-fold higher compared to that in serum [104].

IBX also demonstrated potent activity against both wild-type and azole-resistant strains of A. fumigatus in a murine model of invasive aspergillosis; with significant increase in survival and corresponding reductions in fungal kidney burden and serum galactomannan levels in treated mice compared to untreated mice [105]. Intravenous IBX (7.5 mg/kg/day) in combination with oral isavuconazole (40 mg/kg/day) showed potent activity in a neutropenic model of rabbit invasive pulmonary aspergillosis [106]. This drug combination demonstrated increased survival, reduced fungal pathogen-mediated pulmonary injury, decreased galactomannan antigenemia and serum (1,3)-β-D-glucan levels compared to either drug alone [106].

A prophylactic murine model of Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) found that oral IBX (30 mg/kg BID) reduced total nuclei and asci counts in lung tissue and improved survival; similar results were obtained with TMP/SMX, the gold standard for PCP therapy [81]. IBX reduced number of asci significantly by day 7 with asci being microscopically undetectable by day 14, in a therapeutic murine model of Pneumocystis pneumonia [107]. However, compared to TMP/SMX, total nuclei was only reduced, but was still detectable in the IBX group; survival was better for the TMP/SMX group [107].

6. Clinical efficacy

Currently, there are 12 listed clinical trials for ibrexafungerp (Table 1), eight of which have been completed (https://ClinicalTrials.gov/; accessed on 8 January 2021). Clinical data from at least 1000 participants using both single and multiple daily doses of IBX, as high as 1600 mg, revealed a safe and tolerable profile [108][109][110][111]. Mild adverse events were reported including headaches and gastrointestinal issues such as, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting and abdominal discomfort [108][109][110][111].

Table 1. This is a table showing the details of current clinical trials involving ibrexafungerp.

| Phase | NCT Number | Acronym | Title | Conditions | Drugs | Outcome Measures | Age (yrs) | # | Start Date | End Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | NCT04307082 | ADME | ADME Study of [14C]-Ibrexafungerp in Healthy Male Subjects | Fungal Infection | [14C]-Ibrexafungerp (IBX) | Mass balance|Routes & rates of elimination of [14C]-IBX |Number of subjects with treatment-emergent adverse events | 30–65 | 6 | 5 December 2019 | 30 June 2020 |

| Phase 1 | NCT04092751 | Study to Evaluate the Effect of SCY-078 (Ibrexafungerp) on the PK of Pravastatin in Healthy Subjects | Pharmacokinetics | PRA| SCY-078 plus PRA | Pharmacokinetics of PRA + SCY-078: AUC, Cmax, Tmax, Half-life |Safety & tolerability of the oral combination PRA + SCY-078 | 18–55 | 28 | 22 November 2019 | 20 December 2019 | |

| Phase 1 | NCT04092725 | Study to Evaluate the Effect of SCY-078 on the PK of Dabigatran in Healthy Subjects | Pharmacokinetics | DAB|SCY-078 plus DAB | Pharmacokinetics of DAB + SCY-078: AUC, Cmax, Tmax, Half-life |Safety & tolerability of the oral combination DAB + SCY-078 | 18–55 | 36 | 9 September 2019 | 3 January 2020 | |

| Phase 2 | NCT02244606 | Oral Ibrexafungerp (SCY-078) vs Standard-of-Care Following IV Echinocandin in the Treatment of Invasive Candidiasis | Mycoses, Candidiasis, Invasive, Candidemia | SCY-078|Fluconazole| Micafungin | Safety & tolerability, assessed by adverse events, clinical laboratory results, physical examination findings, ECG results, & vital sign measurements|Dose of SCY-078 that achieves the target exposure (AUC)|Global response| Clinical response| Microbiological response|Relapse | 18–80 | 27 | 1 September 2014 | August 2016 | |

| Phase 2 | NCT02679456 | Safety and Efficacy of Oral Ibrexafungerp (SCY-078) vs. Oral Fluconazole in Subjects With Vulvovaginal Candidiasis | Vulvovaginal Candidiasis | SCY-078|Fluconazole | % of subjects achieving therapeutic cure at TOC visit (Day 24 +/-3)|% of subjects with recurrence of VVC during the observation period | 18–65 | 96 | 1 November 2015 | 5 August 2016 | |

| Phase 2 | NCT03253094 | DOVE | An Active-Controlled, Dose-Finding Study of Oral IBX vs. Oral Fluconazole in Subjects With Acute Vulvovaginal Candidiasis | Candida Vulvovaginitis | Fluconazole|SCY-078 | Clinical cure (complete resolution of signs & symptoms)|Co-occurrence of clinical & mycological cure | 18–100 | 186 | 1 August 2017 | 4 May 2018 |

| Phase 2 | NCT03672292 | SCYNERGIA | Study to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of the Coadministration of Ibrexafungerp (SCY-078) With Voriconazole in Patients With Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis | Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis | SCY-078|Voriconazole| Oral Placebo Tablets | Adverse events; discontinuation due to AE; death|Composite clinical, radiological & mycological response (global response)| Death| Change in serum GMI|Study & comparator plasma concentrations | ≥18 | 60 | 22 January 2019 | 7 June 2021 |

| Phase 3 | NCT03987620 | Vanish 306 | Efficacy and Safety of Oral Ibrexafungerp (SCY-078) vs. Placebo in Subjects With Acute Vulvovaginal Candidiasis | Candida Vulvovaginitis | Ibrexafungerp|Placebo | Clinical cure (complete resolution of signs & symptoms)|Mycological eradication (negative culture for growth of yeast)|Clinical cure & mycological eradication (responder outcome)|Complete resolution of signs 7 symptoms at follow-up|Safety & tolerability of IBX | ≥12 | 366 | 7 June 2019 | 29 April 2020 |

| Phase 3 | NCT03734991 | Vanish 303 | Efficacy and Safety of Oral Ibrexafungerp (SCY-078) vs. Placebo in Subjects With Acute Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (VANISH 303) | Candida Vulvovaginitis | Ibrexafungerp|Placebo | Clinical cure (complete resolution of signs & symptoms) | Mycological eradication (negative culture for yeast growth) |Clinical cure & mycological eradication (responder outcome) |Complete resolution of signs & symptoms at follow-up| subjects with treatment-related adverse events | ≥12 | 376 | 4 January 2019 | 4 September 2019 |

| Phase 3 | NCT03059992 | FURI | Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Ibrexafungerp in Patients With Fungal Diseases That Are Refractory to or Intolerant of Standard Antifungal Treatment | Candidiasis (Invasive, Mucocutaneous, Recurrent Vulvovaginal)| Coccidioido- mycosis| Histoplasmosis| Blastomycosis |Aspergillosis (Chronic & Invasive Pulmonary, Allergic Bronchopulmonary |Other Emerging Fungi | Ibrexafungerp | Assessment of Global Response|Assessment of Recurrence of Baseline Fungal Infection|Assessment of survival | ≥12 | 200 | 1 April 2017 | 5 December 2021 |

| Phase 3 | NCT04029116 | CANDLE | Phase 3 Study of Oral Ibrexafungerp (SCY-078) Vs. Placebo in Subjects With Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (VVC) | Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis | Fluconazole Tablet| IBX| Placebo oral tablet | Clinical Success|The percentage of subjects with no Mycologically Proven Recurrence|Safety & tolerability | ≥12 | 320 | 23 September 2019 | September, 2021 |

| Phase 3 | NCT03363841 | CARES | Open-Label Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Oral Ibrexafungerp (SCY-078) in Patients With Candidiasis Caused by Candida Auris (CARES) | Candidiasis, Invasive Candidemia | SCY-078 | Efficacy as measured by % of subjects with global success at end of treatment|Participants with treatment-related Adverse Events |Participants with Discontinuations due to Adverse Events |Recurrence of Baseline Fungal Infection| Survival | ≥18 | 30 | 15 November 2017 | 15 May 2021 |

In a prospective phase 2 (NCT02244606) randomized, open-label, multi-centre study in patients with invasive candidiasis including candidaemia, IBX administered as an oral step-down treatment after echinocandin therapy, was compared to the standard of care (SOC) treatments: either oral fluconazole or intravenous micafungin for fluconazole-resistant isolates [108]. Efficacy was determined by assessment of global response, with a favourable global response defined as resolution of signs and symptoms (clinical response) and negative Candida cultures (microbiological response), evaluated at the end of therapy [108]. The global response was similar between the IBX (500 mg: 71%; 750 mg: 86%) and SOC (75%) arms, although 750 mg of IBX gave a higher response rate [108]. An ongoing, open-label, single-arm, phase 3 study (CARES: NCT03363841), expected to end in May 2021, is evaluating the efficacy of IBX in patients with Candida auris infections. In preliminary results, infection were completely resolved (culture negative) in two cases after treatment with IBX, including a case with difficult-to-treat C. auris that persisted after treatment with fluconazole and micafungun [112].

A phase 2, randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, dose-finding study (DOVE: NCT03253094) was done to compare the efficacy of oral ibrexafungerp to oral fluconazole (FLU) in patients with acute vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) [113]. The primary endpoints were clinical cure (complete resolution of all signs and symptoms) and mycological eradication (negative culture for yeast) at the test of cure (TOC) visit on day 10 [113]. The clinical cure (52% vs. 58%) and mycological eradication (63% vs. 63%) rates were similar for IBX and FLU, respectively; however, after 25 days, clinical cure (70% vs. 50%) and mycological eradication (48% vs. 38%) rates were higher for IBX compared to FLU, respectively [113]. In two phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials in patients with acute vulvovaginal candidiasis, VANISH 303 (NCT03734991) and VANISH 306 (NCT03987620), with the same end points as the DOVE study, complete resolution of all vaginal signs and symptoms by test of cure (day 10) date was significantly higher in the IBX groups compared to placebo [114][115]. In VANISH 303, clinical cure, mycological eradication, clinical improvement at TOC date and complete resolution of symptoms at day 25 were 51% vs. 29%, 50% vs. 19%, 64% vs. 37%, and 60% vs. 45%, respectively, in the IBX group compared to the placebo [114]. Similarly in VANISH 306, clinical cure, mycological eradication, clinical improvement and resolution of symptoms were 63% vs. 44%, 59% vs. 30%, 72% vs. 55%, and 74% vs. 52%, respectively, in the IBX group compared to the placebo [115]. A large (320 participants) multicentre, randomized, double-blind phase 3 study (CANDLE: NCT04029116) to investigate the efficacy of IBX compared placebo in participants with recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis is currently ongoing and expected to end in September 2021 [116].

A phase 3 open-label single-arm study (FURI: NCT03059992) is investigating the efficacy of IBX in patients, with Candida and Aspergillus disease, who are either intolerant of or refractory to standard of care antifungal treatment [117]. The primary end-point is global success, defined as composite assessment of clinical, microbiological, serological and/or radiological responses at end of treatment [117]. Preliminary data have shown that the majority of the patients (83%) had either a complete or partial response (56%) or stable disease (27%), but 15% of the patients did not respond to IBX and 2% were indeterminate [117]. The FURI study was expanded to include other fungal diseases such as coccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis and other emerging fungi (Table 1).

References

- Douglas, C.M. Fungal beta(1,3)-D-glucan synthesis. Med. Mycol. 2001, 39 (Suppl. S1), 55–66.

- Mikamo, H.; Sato, Y.; Tamaya, T. In vitro antifungal activity of FK463, a new water-soluble echinocandin-like lipopeptide. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2000, 46, 485–487.

- Denning, D.W. Echinocandin antifungal drugs. Lancet 2003, 362, 1142–1151.

- Merck Research Laboratories. Cancidas (Caspofungin Acetate) Injection. Application No.: 21-227. Approval Date: 26 January 2001. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Division of Special Pathogen and Immunologic Drug Products. Available online: (accessed on 29 December 2020).

- Feldmesser, M.; Kress, Y.; Mednick, A.; Casadevall, A. The effect of the echinocandin analogue caspofungin on cell wall glucan synthesis by Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Infect. Dis. 2000, 182, 1791–1795.

- Kurtz, M.B.; Rex, J.H. Glucan synthase inhibitors as antifungal agents. Adv. Protein Chem. 2001, 56, 423–475.

- Chandrasekar, P.H.; Sobel, J.D. Micafungin: A new echinocandin. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 42, 1171–1178.

- Vazquez, J.A.; Sobel, J.D. Anidulafungin: A novel echinocandin. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 43, 215–222.

- Pelaez, F.; Cabello, A.; Platas, G.; Diez, M.T.; Gonzalez del Val, A.; Basilio, A.; Martan, I.; Vicente, F.; Bills, G.E.; Giacobbe, R.A.; et al. The discovery of enfumafungin, a novel antifungal compound produced by an endophytic Hormonema species biological activity and taxonomy of the producing organisms. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2000, 23, 333–343.

- PubChem [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US), National Center for Biotechnology Information; 2004-.PubChem Compound Summary. Available online: (accessed on 30 December 2020).

- Coad, B.R.; Lamont-Friedrich, S.J.; Gwynne, L.; Jasieniak, M.; Griesser, S.S.; Traven, A.; Peleg, A.Y.; Griesser, H.J. Surface coatings with covalently attached caspofungin are effective in eliminating fungal pathogens. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 8469–8476.

- Onishi, J.; Meinz, M.; Thompson, J.; Curotto, J.; Dreikorn, S.; Rosenbach, M.; Douglas, C.; Abruzzo, G.; Flattery, A.; Kong, L.; et al. Discovery of novel antifungal (1,3)-beta-D-glucan synthase inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 368–377.

- Davis, M.R.; Donnelley, M.A.; Thompson, G.R. Ibrexafungerp: A novel oral glucan synthase inhibitor. Med. Mycol. 2020, 58, 579–592.

- Azie, N. A Phase 2b, Dose Finding Study Evaluating Oral Ibrexafungerp in Moderate to Severe Acute Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (DOVE). In Proceedings of the 3rd ISIDOG Congress, Porto, Portugal, 31 Octorber–3 November 2019; Available online: (accessed on 29 December 2020).

- Apgar, J.M.; Wilkening, R.R.; Parker, D.L., Jr.; Meng, D.; Wildonger, K.J.; Sperbeck, D.; Greenlee, M.L.; Balkovec, J.M.; Flattery, A.M.; Abruzzo, G.K.; et al. Ibrexafungerp: An orally active beta-1,3-glucan synthesis inhibitor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2020.

- Scynexis. The World Health Organization Recognizes New Antifungal Class by Granting “ibrexafungerp” to SCYNEXIS as the International Non-Proprietary Name for SCY-078. SCYNEXIS, Inc. Press Release Online. 2018. Available online: (accessed on 29 December 2020).

- Garcia-Rubio, R.; de Oliveira, H.C.; Rivera, J.; Trevijano-Contador, N. The Fungal Cell Wall: Candida, Cryptococcus, and Aspergillus Species. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2993.

- Ruiz-Herrera, J.; Ortiz-Castellanos, L. Cell wall glucans of fungi. A review. Cell Surf. 2019, 5, 100022.

- Fleet, G.H. Composition and structure of yeast cell walls. Curr. Top Med. Mycol. 1985, 1, 24–56.

- Deresinski, S.C.; Stevens, D.A. Caspofungin. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003, 36, 1445–1457.

- Latge, J.P. The cell wall: A carbohydrate armour for the fungal cell. Mol. Microbiol. 2007, 66, 279–290.

- Mazur, P.; Morin, N.; Baginsky, W.; el-Sherbeini, M.; Clemas, J.A.; Nielsen, J.B.; Foor, F. Differential expression and function of two homologous subunits of yeast 1,3-beta-D-glucan synthase. Mol. Cell Biol. 1995, 15, 5671–5681.

- Dijkgraaf, G.J.; Abe, M.; Ohya, Y.; Bussey, H. Mutations in Fks1p affect the cell wall content of beta-1,3- and beta-1,6-glucan in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 2002, 19, 671–690.

- Kondoh, O.; Tachibana, Y.; Ohya, Y.; Arisawa, M.; Watanabe, T. Cloning of the RHO1 gene from Candida albicans and its regulation of beta-1,3-glucan synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 1997, 179, 7734–7741.

- Shematek, E.M.; Braatz, J.A.; Cabib, E. Biosynthesis of the yeast cell wall. I. Preparation and properties of beta-(1 leads to 3) glucan synthetase. J. Biol. Chem. 1980, 255, 888–894.

- Pfaller, M.A.; Messer, S.A.; Motyl, M.R.; Jones, R.N.; Castanheira, M. In vitro activity of a new oral glucan synthase inhibitor (MK-3118) tested against Aspergillus spp. by CLSI and EUCAST broth microdilution methods. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 1065–1068.

- Walker, S.S.; Xu, Y.; Triantafyllou, I.; Waldman, M.F.; Mendrick, C.; Brown, N.; Mann, P.; Chau, A.; Patel, R.; Bauman, N.; et al. Discovery of a novel class of orally active antifungal beta-1,3-D-glucan synthase inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 5099–5106.

- Scorneaux, B.; Angulo, D.; Borroto-Esoda, K.; Ghannoum, M.; Peel, M.; Wring, S. SCY-078 Is Fungicidal against Candida Species in Time-Kill Studies. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61.

- Bowman, J.C.; Hicks, P.S.; Kurtz, M.B.; Rosen, H.; Schmatz, D.M.; Liberator, P.A.; Douglas, C.M. The antifungal echinocandin caspofungin acetate kills growing cells of Aspergillus fumigatus in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 3001–3012.

- Ghannoum, M.; Long, L.; Larkin, E.L.; Isham, N.; Sherif, R.; Borroto-Esoda, K.; Barat, S.; Angulo, D. Evaluation of the Antifungal Activity of the Novel Oral Glucan Synthase Inhibitor SCY-078, Singly and in Combination, for the Treatment of Invasive Aspergillosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62.

- Jimenez-Ortigosa, C.; Perez, W.B.; Angulo, D.; Borroto-Esoda, K.; Perlin, D.S. De Novo Acquisition of Resistance to SCY-078 in Candida glabrata Involves FKS Mutations That both Overlap and Are Distinct from Those Conferring Echinocandin Resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61.

- Perlin, D.S. Resistance to echinocandin-class antifungal drugs. Drug Resist. Updat. 2007, 10, 121–130.

- Garcia-Effron, G.; Lee, S.; Park, S.; Cleary, J.D.; Perlin, D.S. Effect of Candida glabrata FKS1 and FKS2 mutations on echinocandin sensitivity and kinetics of 1,3-beta-D-glucan synthase: Implication for the existing susceptibility breakpoint. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 3690–3699.

- Park, S.; Kelly, R.; Kahn, J.N.; Robles, J.; Hsu, M.J.; Register, E.; Li, W.; Vyas, V.; Fan, H.; Abruzzo, G.; et al. Specific substitutions in the echinocandin target Fks1p account for reduced susceptibility of rare laboratory and clinical Candida sp. isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 3264–3273.

- Ben-Ami, R.; Garcia-Effron, G.; Lewis, R.E.; Gamarra, S.; Leventakos, K.; Perlin, D.S.; Kontoyiannis, D.P. Fitness and virulence costs of Candida albicans FKS1 hot spot mutations associated with echinocandin resistance. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 204, 626–635.

- Alexander, B.D.; Johnson, M.D.; Pfeiffer, C.D.; Jimenez-Ortigosa, C.; Catania, J.; Booker, R.; Castanheira, M.; Messer, S.A.; Perlin, D.S.; Pfaller, M.A. Increasing echinocandin resistance in Candida glabrata: Clinical failure correlates with presence of FKS mutations and elevated minimum inhibitory concentrations. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 56, 1724–1732.

- Pham, C.D.; Iqbal, N.; Bolden, C.B.; Kuykendall, R.J.; Harrison, L.H.; Farley, M.M.; Schaffner, W.; Beldavs, Z.G.; Chiller, T.M.; Park, B.J.; et al. Role of FKS Mutations in Candida glabrata: MIC values, echinocandin resistance, and multidrug resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 4690–4696.

- Chowdhary, A.; Prakash, A.; Sharma, C.; Kordalewska, M.; Kumar, A.; Sarma, S.; Tarai, B.; Singh, A.; Upadhyaya, G.; Upadhyay, S.; et al. A multicentre study of antifungal susceptibility patterns among 350 Candida auris isolates (2009-17) in India: Role of the ERG11 and FKS1 genes in azole and echinocandin resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 891–899.

- Kordalewska, M.; Lee, A.; Park, S.; Berrio, I.; Chowdhary, A.; Zhao, Y.; Perlin, D.S. Understanding Echinocandin Resistance in the Emerging Pathogen Candida auris. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62.

- Naicker, S.D.; Magobo, R.E.; Zulu, T.G.; Maphanga, T.G.; Luthuli, N.; Lowman, W.; Govender, N.P. Two echinocandin-resistant Candida glabrata FKS mutants from South Africa. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 2016, 11, 24–26.

- Nunnally, N.S.; Etienne, K.A.; Angulo, D.; Lockhart, S.R.; Berkow, E.L. In Vitro Activity of Ibrexafungerp, a Novel Glucan Synthase Inhibitor against Candida glabrata Isolates with FKS Mutations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63.

- Perfect, J.R. The antifungal pipeline: A reality check. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 603–616.

- Pfaller, M.A.; Pappas, P.G.; Wingard, J.R. Invasive Fungal Pathogens: Current Epidemiological Trends. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 43, S3–S14.

- Brown, G.D.; Denning, D.W.; Gow, N.A.; Levitz, S.M.; Netea, M.G.; White, T.C. Hidden killers: Human fungal infections. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 165rv113.

- WHO. Antimicrobial Resistance: Global Report on Surveillance; WHO (World Health Organization): Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; Available online: (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Arendrup, M.C. Update on antifungal resistance in Aspergillus and Candida. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014, 20 (Suppl. S6), 42–48.

- Pfaller, M.A.; Diekema, D.J. Rare and emerging opportunistic fungal pathogens: Concern for resistance beyond Candida albicans and Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 4419–4431.

- Wickes, B.L. Analysis of a Candida auris Outbreak Provides New Insights into an Emerging Pathogen. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 58.

- Van Schalkwyk, E.; Mpembe, R.S.; Thomas, J.; Shuping, L.; Ismail, H.; Lowman, W.; Karstaedt, A.S.; Chibabhai, V.; Wadula, J.; Avenant, T.; et al. Epidemiologic Shift in Candidemia Driven by Candida auris, South Africa, 2016–2017(1). Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 1698–1707.

- Govender, N.P.; Patel, J.; Magobo, R.E.; Naicker, S.; Wadula, J.; Whitelaw, A.; Coovadia, Y.; Kularatne, R.; Govind, C.; Lockhart, S.R.; et al. Emergence of azole-resistant Candida parapsilosis causing bloodstream infection: Results from laboratory-based sentinel surveillance in South Africa. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 1994–2004.

- Fridkin, S.K.; Jarvis, W.R. Epidemiology of nosocomial fungal infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1996, 9, 499–511.

- Pfaller, M.A.; Messer, S.A.; Moet, G.J.; Jones, R.N.; Castanheira, M. Candida bloodstream infections: Comparison of species distribution and resistance to echinocandin and azole antifungal agents in Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and non-ICU settings in the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (2008–2009). Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2011, 38, 65–69.

- Chowdhary, A.; Sharma, C.; Duggal, S.; Agarwal, K.; Prakash, A.; Singh, P.K.; Jain, S.; Kathuria, S.; Randhawa, H.S.; Hagen, F.; et al. New clonal strain of Candida auris, Delhi, India. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013, 19, 1670–1673.

- Chowdhary, A.; Kumar, V.A.; Sharma, C.; Prakash, A.; Agarwal, K.; Babu, R.; Dinesh, K.R.; Karim, S.; Singh, S.K.; Hagen, F.; et al. Multidrug-resistant endemic clonal strain of Candida auris in India. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2014, 33, 919–926.

- Lockhart, S.R.; Etienne, K.A.; Vallabhaneni, S.; Farooqi, J.; Chowdhary, A.; Govender, N.P.; Colombo, A.L.; Calvo, B.; Cuomo, C.A.; Desjardins, C.A.; et al. Simultaneous Emergence of Multidrug-Resistant Candida auris on 3 Continents Confirmed by Whole-Genome Sequencing and Epidemiological Analyses. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017, 64, 134–140.

- Lockhart, S.R.; Jackson, B.R.; Vallabhaneni, S.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Pappas, P.G.; Chiller, T. Thinking beyond the Common Candida Species: Need for Species-Level Identification of Candida Due to the Emergence of Multidrug-Resistant Candida auris. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2017, 55, 3324–3327.

- Zhu, Y.C.; Barat, S.A.; Borroto-Esoda, K.; Angulo, D.; Chaturvedi, S.; Chaturvedi, V. Pan-resistant Candida auris isolates from the outbreak in New York are susceptible to ibrexafungerp (a glucan synthase inhibitor). Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 105922.

- Ostrowsky, B.; Greenko, J.; Adams, E.; Quinn, M.; O’Brien, B.; Chaturvedi, V.; Berkow, E.; Vallabhaneni, S.; Forsberg, K.; Chaturvedi, S.; et al. Candida auris Isolates Resistant to Three Classes of Antifungal Medications-New York, 2019. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 6–9.

- Osei Sekyere, J. Candida auris: A systematic review and meta-analysis of current updates on an emerging multidrug-resistant pathogen. Microbiologyopen 2018, 7, e00578.

- Sabino, R.; Verissimo, C.; Pereira, A.A.; Antunes, F. Candida auris, an Agent of Hospital-Associated Outbreaks: Which Challenging Issues Do We Need to Have in Mind? Microorganisms 2020, 8, 181.

- Chaabane, F.; Graf, A.; Jequier, L.; Coste, A.T. Review on Antifungal Resistance Mechanisms in the Emerging Pathogen Candida auris. Front Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2788.

- Forsberg, K.; Woodworth, K.; Walters, M.; Berkow, E.L.; Jackson, B.; Chiller, T.; Vallabhaneni, S. Candida auris: The recent emergence of a multidrug-resistant fungal pathogen. Med. Mycol. 2019, 57, 1–12.

- Govender, N.P.; Magobo, R.E.; Mpembe, R.; Mhlanga, M.; Matlapeng, P.; Corcoran, C.; Govind, C.; Lowman, W.; Senekal, M.; Thomas, J. Candida auris in South Africa, 2012–2016. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018, 24, 2036–2040.

- Magobo, R.E.; Corcoran, C.; Seetharam, S.; Govender, N.P. Candida auris-associated candidemia, South Africa. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 1250–1251.

- Patterson, T.F.; Kirkpatrick, W.R.; White, M.; Hiemenz, J.W.; Wingard, J.R.; Dupont, B.; Rinaldi, M.G.; Stevens, D.A.; Graybill, J.R. Invasive aspergillosis. Disease spectrum, treatment practices, and outcomes. I3 Aspergillus Study Group. Medicine 2000, 79, 250–260.

- Lin, S.J.; Schranz, J.; Teutsch, S.M. Aspergillosis case-fatality rate: Systematic review of the literature. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001, 32, 358–366.

- Vermeulen, E.; Maertens, J.; de Bel, A.; Nulens, E.; Boelens, J.; Surmont, I.; Mertens, A.; Boel, A.; Lagrou, K. Nationwide Surveillance of Azole Resistance in Aspergillus Diseases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 4569–4576.

- Snelders, E.; van der Lee, H.A.; Kuijpers, J.; Rijs, A.J.; Varga, J.; Samson, R.A.; Mellado, E.; Donders, A.R.; Melchers, W.J.; Verweij, P.E. Emergence of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus and spread of a single resistance mechanism. PLoS Med. 2008, 5, e219.

- Snelders, E.; Huis In ‘t Veld, R.A.; Rijs, A.J.; Kema, G.H.; Melchers, W.J.; Verweij, P.E. Possible environmental origin of resistance of Aspergillus fumigatus to medical triazoles. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 4053–4057.

- Mitchell, T.G.; Perfect, J.R. Cryptococcosis in the era of AIDS–100 years after the discovery of Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1995, 8, 515–548.

- Walzer, P.D.; Evans, H.E.; Copas, A.J.; Edwards, S.G.; Grant, A.D.; Miller, R.F. Early predictors of mortality from Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in HIV-infected patients: 1985-2006. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 46, 625–633.

- Duncan, R.A.; von Reyn, C.F.; Alliegro, G.M.; Toossi, Z.; Sugar, A.M.; Levitz, S.M. Idiopathic CD4+ T-lymphocytopenia--four patients with opportunistic infections and no evidence of HIV infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993, 328, 393–398.

- Reid, A.B.; Chen, S.C.; Worth, L.J. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in non-HIV-infected patients: New risks and diagnostic tools. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 24, 534–544.

- Porollo, A.; Meller, J.; Joshi, Y.; Jaiswal, V.; Smulian, A.G.; Cushion, M.T. Analysis of current antifungal agents and their targets within the Pneumocystis carinii genome. Curr. Drug Targets 2012, 13, 1575–1585.

- Kaneshiro, E.S.; Ellis, J.E.; Jayasimhulu, K.; Beach, D.H. Evidence for the presence of “metabolic sterols” in Pneumocystis: Identification and initial characterization of Pneumocystis carinii sterols. J. Eukaryot Microbiol. 1994, 41, 78–85.

- Malamba, S.; Sandison, T.; Lule, J.; Reingold, A.; Walker, J.; Dorsey, G.; Mermin, J. Plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase and dihyropteroate synthase mutations and the use of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis among persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2010, 82, 766–771.

- Chen, S.C.; Slavin, M.A.; Sorrell, T.C. Echinocandin antifungal drugs in fungal infections: A comparison. Drugs 2011, 71, 11–41.

- Eschenauer, G.; Depestel, D.D.; Carver, P.L. Comparison of echinocandin antifungals. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2007, 3, 71–97.

- De la Torre, P.; Meyer, D.K.; Reboli, A.C. Anidulafungin: A novel echinocandin for candida infections. Future Microbiol. 2008, 3, 593–601.

- Jimenez-Ortigosa, C.; Paderu, P.; Motyl, M.R.; Perlin, D.S. Enfumafungin derivative MK-3118 shows increased in vitro potency against clinical echinocandin-resistant Candida Species and Aspergillus species isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 1248–1251.

- Cushion, M.; Ashbaugh, A.; Borroto-Esoda, K.; Barat, S.A.; Angulo, D. SCY-078 demonstrates antifungal activity against pneumocystis in a prophylactic murine model of pneumocystis pneumonia. ASM Microbe Online 2018.

- Espinel-Ingroff, A. Comparison of In vitro activities of the new triazole SCH56592 and the echinocandins MK-0991 (L-743,872) and LY303366 against opportunistic filamentous and dimorphic fungi and yeasts. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1998, 36, 2950–2956.

- Maligie, M.A.; Selitrennikoff, C.P. Cryptococcus neoformans resistance to echinocandins: (1,3)beta-glucan synthase activity is sensitive to echinocandins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 2851–2856.

- Marcos-Zambrano, L.J.; Gomez-Perosanz, M.; Escribano, P.; Bouza, E.; Guinea, J. The novel oral glucan synthase inhibitor SCY-078 shows in vitro activity against sessile and planktonic Candida spp. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 1969–1976.

- Larkin, E.; Hager, C.; Chandra, J.; Mukherjee, P.K.; Retuerto, M.; Salem, I.; Long, L.; Isham, N.; Kovanda, L.; Borroto-Esoda, K.; et al. The Emerging Pathogen Candida auris: Growth Phenotype, Virulence Factors, Activity of Antifungals, and Effect of SCY-078, a Novel Glucan Synthesis Inhibitor, on Growth Morphology and Biofilm Formation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61.

- Pfaller, M.A.; Messer, S.A.; Rhomberg, P.R.; Borroto-Esoda, K.; Castanheira, M. Differential Activity of the Oral Glucan Synthase Inhibitor SCY-078 against Wild-Type and Echinocandin-Resistant Strains of Candida Species. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61.

- Schell, W.A.; Jones, A.M.; Borroto-Esoda, K.; Alexander, B.D. Antifungal Activity of SCY-078 and Standard Antifungal Agents against 178 Clinical Isolates of Resistant and Susceptible Candida Species. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61.

- Berkow, E.L.; Angulo, D.; Lockhart, S.R. In Vitro Activity of a Novel Glucan Synthase Inhibitor, SCY-078, against Clinical Isolates of Candida auris. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61.

- Ghannoum, M.; Long, L.; Isham, N.; Hager, C.; Wilson, R.; Borroto-Esoda, K.; Barat, S.; Angulo, D. Activity of a novel 1,3-beta-D-glucan Synthase Inhibitor, Ibrexafungerp (formerly SCY-078), Against Candida glabrata. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019.

- Arendrup, M.C.; Jorgensen, K.M.; Hare, R.K.; Chowdhary, A. In Vitro Activity of Ibrexafungerp (SCY-078) against Candida auris Isolates as Determined by EUCAST Methodology and Comparison with Activity against C. albicans and C. glabrata and with the Activities of Six Comparator Agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64.

- Zhu, Y.C.; Barat, S.A.; Borroto-Esoda, K.; Angulo, D.; Chaturvedi, S.; Chaturvedi, V. In vitro Efficacy of Novel Glucan Synthase Inhibitor, Ibrexafungerp (SCY-078), Against Multidrug- and Pan-resistant Candida auris Isolates from the Outbreak in New York. BioRxiv 2020.

- Chandra, J.; Mukherjee, P.K.; Leidich, S.D.; Faddoul, F.F.; Hoyer, L.L.; Douglas, L.J.; Ghannoum, M.A. Antifungal resistance of candidal biofilms formed on denture acrylic in vitro. J. Dent. Res. 2001, 80, 903–908.

- Cowen, L.E.; Sanglard, D.; Howard, S.J.; Rogers, P.D.; Perlin, D.S. Mechanisms of Antifungal Drug Resistance. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect Med. 2014, 5, a019752.

- Ghannoum, M.; Long, L.; Sherif, R.; Abidi, F.Z.; Borroto-Esoda, K.; Barat, S.; Angulo, D.; Wiederhold, N. Determination of Antifungal Activity of SCY-078, a Novel Glucan Synthase Inhibitor, Against a broad panel of Rare Pathogenic Fungi. ASM Microbe Online 2020.

- Larkin, E.L.; Long, L.; Isham, N.; Borroto-Esoda, K.; Barat, S.; Angulo, D.; Wring, S.; Ghannoum, M. A Novel 1,3-Beta-d-Glucan Inhibitor, Ibrexafungerp (Formerly SCY-078), Shows Potent Activity in the Lower pH Environment of Vulvovaginitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63.

- Odds, F.C.; Brown, A.J.; Gow, N.A. Antifungal agents: Mechanisms of action. Trends Microbiol. 2003, 11, 272–279.

- Rocha, E.M.; Garcia-Effron, G.; Park, S.; Perlin, D.S. A Ser678Pro substitution in Fks1p confers resistance to echinocandin drugs in Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 4174–4176.

- Lamoth, F.; Alexander, B.D. Antifungal activities of SCY-078 (MK-3118) and standard antifungal agents against clinical non-Aspergillus mold isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 4308–4311.

- Wiederhold, N.P.; Najvar, L.K.; Jaramillo, R.; Olivo, M.; Pizzini, J.; Catano, G.; Patterson, T.F. Oral glucan synthase inhibitor SCY-078 is effective in an experimental murine model of invasive candidiasis caused by WT and echinocandin-resistant Candida glabrata. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 448–451.

- Lepak, A.J.; Marchillo, K.; Andes, D.R. Pharmacodynamic target evaluation of a novel oral glucan synthase inhibitor, SCY-078 (MK-3118), using an in vivo murine invasive candidiasis model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 1265–1272.

- Wring, S.A.; Randolph, R.; Park, S.; Abruzzo, G.; Chen, Q.; Flattery, A.; Garrett, G.; Peel, M.; Outcalt, R.; Powell, K.; et al. Preclinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamic Target of SCY-078, a First-in-Class Orally Active Antifungal Glucan Synthesis Inhibitor, in Murine Models of Disseminated Candidiasis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61.

- Ghannoum, M.; Isham, N.; Angulo, D.; Borroto-Esoda, K.; Barat, S.; Long, L. Efficacy of Ibrexafungerp (SCY-078) against Candida auris in an In Vivo Guinea Pig Cutaneous Infection Model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64.

- Vergidis, P.; Clancy, C.J.; Shields, R.K.; Park, S.Y.; Wildfeuer, B.N.; Simmons, R.L.; Nguyen, M.H. Intra-Abdominal Candidiasis: The Importance of Early Source Control and Antifungal Treatment. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153247.

- Lee, A.; Prideaux, B.; Zimmerman, M.; Carter, C.; Barat, S.; Angulo, D.; Dartois, V.; Perlin, D.S.; Zhao, Y. Penetration of Ibrexafungerp (Formerly SCY-078) at the Site of Infection in an Intra-abdominal Candidiasis Mouse Model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64.

- Borroto-Esoda, K.; Barat, S.; Angulo, D.; Holden, K.; Warn, P. SCY-078 Demonstrates Significant Antifungal Activity in a Murine Model of Invasive Aspergillosis. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2017, 4, S472.

- Petraitis, V.; Petraitiene, R.; Katragkou, A.; Maung, B.B.W.; Naing, E.; Kavaliauskas, P.; Barat, S.; Borroto-Esoda, K.; Azie, N.; Angulo, D.; et al. Combination Therapy with Ibrexafungerp (Formerly SCY-078), a First-in-Class Triterpenoid Inhibitor of (1-->3)-beta-d-Glucan Synthesis, and Isavuconazole for Treatment of Experimental Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64.

- Barat, S.A.; Borroto-Esoda, K.; Angulo, D.; Ashbaugh, A.; Cushion, M. Efficacy of Ibrexafungerp (formerly SCY-078) in a Murine Treatment Model of Pneumocystis Pneumonia. ASM Microbe Online. 2019. Available online: (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Spec, A.; Pullman, J.; Thompson, G.R.; Powderly, W.G.; Tobin, E.H.; Vazquez, J.; Wring, S.A.; Angulo, D.; Helou, S.; Pappas, P.G.; et al. MSG-10: A Phase 2 study of oral ibrexafungerp (SCY-078) following initial echinocandin therapy in non-neutropenic patients with invasive candidiasis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74, 3056–3062.

- Wring, S.; Murphy, G.; Atiee, G.; Corr, C.; Hyman, M.; Willett, M.; Angulo, D. Lack of Impact by SCY-078, a First-in-Class Oral Fungicidal Glucan Synthase Inhibitor, on the Pharmacokinetics of Rosiglitazone, a Substrate for CYP450 2C8, Supports the Low Risk for Clinically Relevant Metabolic Drug-Drug Interactions. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 58, 1305–1313.

- Wring, S.; Murphy, G.; Atiee, G.; Corr, C.; Hyman, M.; Willett, M.; Angulo, D. Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Drug-Drug Interaction Potential for Coadministered SCY-078, an Oral Fungicidal Glucan Synthase Inhibitor, and Tacrolimus. Clin. Pharmacol. Drug Dev. 2019, 8, 60–69.

- Azie, N.; Angulo, D.; Dehn, B.; Sobel, J.D. Oral Ibrexafungerp: An investigational agent for the treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2020, 29, 893–900.

- Juneja, D.; Singh, O.; Tarai, B.; Angulo, D. Successful Treatment of Two Patients with Candida auris Candidemia with the Investigational Agent, Oral Ibrexafungerp (formerly SCY-078) from the CARES Study. In Proceedings of the 29th ECCMID Congress, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 13–16 April 2019.

- Cadet, R.; Tufa, M.; Angulo, D.; Nyirjesy, P. A Phase 2b, Dose-Finding Study Evaluating Oral Ibrexafungerp vs Fluconazole in Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (DOVE). Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 133, 113S–114S.

- Schwebke, J.R.; Sorkin-Wells, V.; Azie, N.; Angulo, D.; Sobel, J. Oral ibrexafungerp efficacy and safety in the treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis: A phase 3, randomized, blinded, study vs. placebo (VANISH-303). IDSOG Oral Present. 2020, 223, 964–965.

- Scynexis. SCYNEXIS Announces Positive Top-Line Results from Its Second Pivotal Phase 3 Study (VANISH-306) of Oral Ibrexafungerp for the Treatment of Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (Vaginal Yeast Infection). SCYNEXIS, Inc. Press Release Online. 2020. Available online: (accessed on 29 December 2020).

- Scynexis. SCYNEXIS Completes Patient Enrollment Ahead of Schedule in the Second Pivotal Phase 3 Study (VANISH-306) of Oral Ibrexafungerp for the Treatment of Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (Vaginal Yeast Infection). SCYNEXIS, Inc. Press Release Online. 2020. Available online: (accessed on 29 December 2020).

- Alexander, B.D.; Cornely, O.A.; Pappas, P.G.; Miller, R.; Johnson, M.; Vazquez, J.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Spec, A.; Rautemaa-Richardson, R.; Krause, R.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Oral Ibrexafungerpin 41 Patients with Refractory Fungal Diseases, Interim Analysis of a Phase 3 Open-label Study (FURI). Poster Presented at ID Week 2020 Online. 2019. Available online: (accessed on 29 December 2020).