Video Upload Options

Pandemics cause chaotic situations in supply chains (SC) around the globe, which can lead towards survivability challenges. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is an unprecedented humanitarian crisis that has severely affected global business dynamics. Similar vulnerabilities have been caused by other outbreaks in the past. In these terms, prevention strategies against propagating disruptions require vigilant goal conceptualization and roadmaps. In this respect, there is a need to explore supply chain operation management strategies to overcome the challenges that emerge due to COVID-19-like situations.

1. Introduction

Disruptions to business operations and global supply chains (SC) caused by disasters have led the practitioners and researchers to focus on survivability, which is the most concerning topic these days [1]. There have been several threats, such as climate changes leading to natural disasters, man-made circumstances (in terms of terrorism), and several other potential risks. Consequently, companies look for ways to survive in tough times and sustain their positions after such events. A potential roadmap for ensuring both objectives is to transform their operations and SC activities into transparent, agile, and reliable cyber–physical systems. Many industrial tycoons have started the journey towards digitalization [2].

Moreover, to survive during disasters, the focus on improving market-share, ecological consciousness, and differentiation through technology leadership, along with a reliable and sustainable SC network requires a workable framework. However, approaches such as being lean, green, and resilient, and ensuring sustainability are established, and practiced supporting emerging market requirements. In terms of sustainability, if an SC gets disturbed because of a disaster, the parallel node to the affected location is identified and connected to minimize the disruptions in supplies and demands [3]. Among different types of disasters categorized by the World Health Organization (WHO), epidemic outbreaks have proven to be destructive to human lives as well as economies. The manufacturing setups, which are considered the backbone of any country’s economy, often face full or partial closure in such circumstances. The economic effects surpass territorial boundaries through a globally connected network. At the micro-level, many industrial sectors experience absenteeism of the workforce because many are affected or taking care of affected ones at their residences. This leads to a significant drop in operations and production levels, and sustainable performance gets disturbed [4]. The world has been challenged several times by extraordinary pandemics, which left long-term effects on society, businesses, operations, and SCs [5]. Among these ripple effects, 20 to 50 million people died due to the Spanish Influenza outbreak in 1918–1919. Similarly, the Ebola virus also had unmatched effects on all dimensions. These large-scale losses urged the upgrade of disease risk, prevention, and outbreak management facilities, despite the unavailability of cures [6][7]. Notable outbreaks such as SARS, MERS, AIDS, cholera, and malaria have affected society, as well as the economy, having accumulated effects in the billions of US dollars [8]. Moreover, a lot of waste and environment damages are caused every year [9].

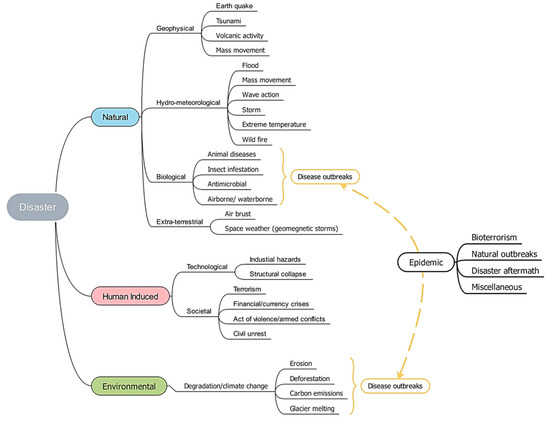

In recent years, the frequency and severity of these disasters have been becoming worse due to several factors. World Health Organization [10] has categorized various types of disasters. The potential types which potentially lead to epidemic outbreaks are classified in Figure 1. The emergencies’ consequence is pandemics, causing unprecedented losses. All SCs, at a local and global level, get affected and face challenges in ensuring logistic and manufacturing operations continuity [11]. Therefore, it is important to address the diseases under a unanimous framework in the current timeline. A few studies have reported that these epidemics are the consequence of climate change and patterns [12]. Businesses are already experiencing disasters. Recently, they have been hit by the highly contagious, unprecedented, and infectious outbreak termed as COVID-19. It is a novel outbreak causing disturbances to human lives and the circular economy [13].

Figure 1. Disaster classification which poses serious threats to global supply chains (SCs). (Source: authors).

2. Discussion on the Findings

2.1. Categorization of Previous Epidemic/Disease Outbreaks and SC Implications

To get an understanding of the impacts of previous outbreaks, a rigorous literature review is summarized in Table 1, categorizing the available research on different epidemics’ effects on the performance of SCs. The content analysis was carried out by focusing on the epidemic and objectives studied in those publications, the problem-solving approaches, and the related implications recommended and proposed in those pandemic situations.

Table 1. Pandemics and the objectives to resolve their impacts on SC.

| Ref | Pandemic | Objectives | Problem-Solving Approaches | Developments/Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27] | Influenza |

|

|

|

| [28][29][30] | Ebola |

|

|

|

| [31][32][33][34] | Cholera |

|

|

|

| [35] | Malaria |

|

|

|

| [36] | Smallpox |

|

|

|

| [5][37][38][39] | COVID-19 |

|

|

|

| [40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48] | General epidemic management/control |

|

|

|

2.2. Multiple Correspondence Analysis

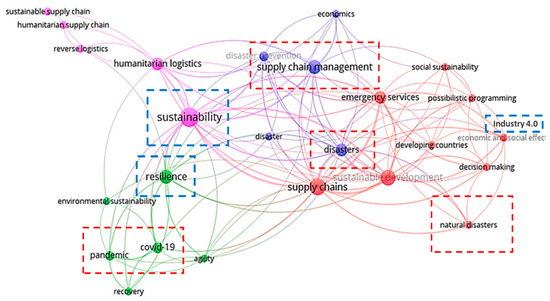

To analyze and establish a conceptual map on the selected domains based on the dataset, multiple correspondence analysis was carried out, and displayed in Figure 2. It is an effective technique for reducing contents and developing a conceptual map [49]. It is a two-dimensional technique that constructs a graphical map of the distribution of word similarities in the data set. These words were acquired from “keywords” and “titles” of the references considered for analysis. The frequency of the words used in the publications determines the size of the circle and text, whereas the color represents different clusters. The keywords “sustainability”, “disasters”, “supply chains”, “supply chain management” and “resilience” were easily identifiable and confirmed the research trends in particular areas. However, other words were displayed as emerging research areas in the SC field.

Figure 2. Conceptual map generated through multiple correspondence analysis.

Moreover, “COVID-19”, “pandemic”, “recovery”, “natural disasters”, “humanitarian supply chain”, and “humanitarian logistics” were also interesting topics for recent scenarios. As represented by the correspondence analysis, “emergency services” recommends areas of effective and efficient resource allocation and logistics planning. As a consequent “resilience”, “disasters”, and “decision making” indicated emerging themes of the research. In this research study, “sustainability”, “pandemic”, “disasters”, “supply chain”, and “emergency services” were visible as impact themes, and were focused to gather the answers to the research questions from the scarce literature. Our study advocates the use of these themes to evaluate the impacts of epidemics and their effects on SCs. From Figure 3, a multiple co-occurrence analysis of the countries of authors affiliation was carried out. The countries “France”, “Germany”, “United States”, “China”, “Iran”, and “India” contributed more to the research on the selected domain. The size of the circle and text represents the frequency of repetition of the countries in the articles.

Figure 3. Multiple co-occurrence analysis of the main countries contributing to the selected research area.

3. Future Research Avenues

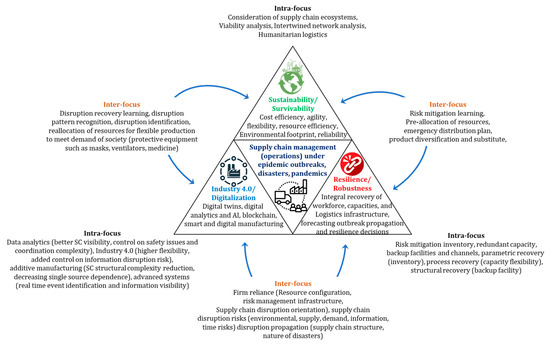

3.1. Sustainability/Survivability Preparedness

To prepare SCs for greater reliability and survival during deeply uncertain environments, first a focus on the preparedness aspect (for survivability) was highlighted by our SLR on the effects of epidemic outbreaks on SCs. On the path of sustainability, these key areas are highlighted more during content analyses, such as cost efficiency, agility, flexibility, resource efficiency, environmental footprint, and reliability. Moreover, there are not only opportunities in the domain of mathematical optimization and simulation, but also with other approaches, for example queuing theory, system dynamics, effective scheduling and forecasting, and knowledge-based systems can be explored [50][40]. This indicates that decision-makers should employ a diverse integrated approach to improving SC survivability and sustainability perspective [51][52][53]. Moreover, simulation-based approaches are commonly used [54] to evaluate different decisions during an epidemic for better response to SC operation disruptions [5][38][55][56]. Simulation is used as a predictive tool to test decisions, massive disruptions, and performance capacities. In addition to this, consideration of SC ecosystems, viability analysis, intertwined network analysis, and humanitarian logistics also play a key role in SC sustainability. However, inter-domain areas overlapping with resilience and robustness include risk mitigation learning, pre-allocation of resources, emergency distribution planning, and product diversification and substitution. Our study sheds more light on the management and allocation of resources, as evident from previous approaches mentioned in Table 1.

Additionally, sustainability itself, as a focus of our SLR is discussed through considering SC ecosystems, and the viability of the system, operations, and network; as well as novel and severe disruptions to SCs and how a circular economy can help to sustain production capacities, and deal with insufficient supply and demand conditions, to ensure short-term and long-term SC sustainability and survivability [8][57]. Moreover, the feedback in SC ecosystems, both positive (cycle of natural resources) or negative (cycle of emissions as a contributor to climate change), and the interactions of SC stakeholders, such as society, organization was also considered. Similarly, workforce development, technological innovations are positive interactions, whereas strikes (SC disruptions and organization-based resilience level), global disruptions (pandemics or epidemic outbreaks causing SC disruptions at survivability level) are negative interactions. Attempts to manage these negative implications are made through a focus on the overlap of sustainability/survivability with industry 4.0/digitalization. “Disruption recovery learning”, “disruption pattern recognition”, and “disruption identification” in highly interconnected digitally assisted SCs can bring integrity through intertwined networks. This requires incorporating all the stakeholder at all levels, such as society, organizations, system, and processes [39]. Moreover, humanitarian logistics and crises regarding SC sustainability are also vital areas to explore further in the field [58][59][60].

3.2. Digital/Industry 4.0 Vigilance

There is an urgent need to evaluate the current technological readiness level for industry 4.0 transformation to firmly combat COVID-19-like future disruptions. Earlier, cutting-edge technologies such as blockchain, additive manufacturing, and artificial intelligence (AI) were not available to industries, but in this epoch, these technologies provide high-end traceability, robustness, and resilience to SCs. First, the analysis of an epidemic outbreak’s effects on SCs can be carried out, followed by an assessment of the current technology level [61], and lastly a framework for developed, under-developed, and developing countries (as dynamics are different in every community) to roadmap the transformation journey. These technologies (artificial intelligence, Industry 4.0) could play a crucial role in SC resilience and robustness against ripple effects [62][63]. In terms of visibility and digital manufacturing networks, we can foresee a viable option for assuring workability during a crisis and the coordination of recovery from future pandemics [58][64]. “Digital twins”, “digital analytics and AI”, and “smart and digital manufacturing” are remarkably good ways forward, and are sure to support SCs. Whereas the overlap of this focus with resilience and robustness of SCs was also identified by our SLR. The collaboration of “Industry 4.0/digitalization” with “resilience/robustness” offers a way forward through firm reliance, in terms of resource configuration and risk management infrastructure [62][65][66].

3.3. Resilience/Robustness Readiness

The next focus on SCs is their readiness to respond to the impacts of remarkably high and unexplored ripple effects. Companies and economies are facing a great depression due to the COVID-19 pandemic [67][68][69]. This is an important aspect of understanding the implications of ripple effects and pandemic stress on SCs, and the possibilities of collapse due to disease and disruption propagation through networks. Though multiple aspects of ripple effects have been simulated and studied in various dimensions they deserve to be explored more [4][56][65]. The journey for resilience and robustness of SCs starts from evaluating ripple effects, then the adaptation of new terms, leading towards the recovery phase. Several tensions in SCs were reported from previous pandemics, as mentioned in Table 1, and several operation management approaches have been used to address resource allocation. Practitioners, decision makers, managers, and experts continuously try to monitor SCs performance, to rigorously evaluate the disruptions, and to make a recovery plan covering all aspects and leaving nothing unexamined. To ensure the recovery plan is successful certain key roles need to be addressed, such as “risk mitigation inventory”, “redundant capacity”, and “backup facilities and channels”. These are the significant areas which are needed to make SCs robust, as well as resilient against such pandemics.

To summarize, SCs must operate with the assistance of operations management approaches and the aspects mentioned in Figure 4; from a resilience and survivability perspective, to avoid supply shortages, and delivering an optimized, responsive, and dynamic decision support model for different stages of disaster, pandemics, and outbreaks, through taking aid from simulations, mathematical optimization, and network and complexity theories.

Figure 4. Framework for the readiness of SCs to combat pandemics.

3.4. A Conclusive Insight

This research study covers the main aspects by classifying different epidemic outbreaks and SC resilience objectives addressed from the view of local as well as global pandemics. The overall insight of our SLR analysis orientates the traditional SCs towards risk, resilience, and sustainable understanding, to tackle severe, destructive, unmatched global disruptions and disasters. Hence, multiple approaches were found significant to address issues during a pandemic [70][58][66]. Therefore, there is always a continuous need, as per the understanding from the analysis of a SLR, to explore existing approaches [61], extend them, or propose new [38][71] ones, to deal with new challenges, and we urge experts to explore the areas mentioned in Table 2 with novel approaches or hybrid techniques.

Table 2. Proposed research extension opportunities and agenda for investigating and effectively responding to an epidemic’s effects on SCs.

| Ref | Literature Gap | Open Questions and Opportunities for Future Research | Potential Solution Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| [72][73][74][75] | Optimized and novel models for sustainable operations in disturbed SCs during epidemic/disasters, for resource allocation in a dynamic environment, and for the development of sustainable SCs and smart production systems in smart cities | How can optimized and novel models help in responding to vulnerable SCs and show robust behavior with SC effects such as shortages, delays, and overhead costs? How new facilities can be developed to cater to the requirements of dynamic disruptive situations? How smart cities can help to support epidemic epicenters? |

Robust optimization; Stochastic programming; Mixed-integer linear programming; Game theory; Dynamic capability |

| [76][77][78][79][80] | Optimized response to humanitarian logistics (forward and reverse), supply chains, and operations | How can the local and global SCs plan to respond to disasters at a local as well as global scale in terms of humanitarian relief? How to prepare a flexible humanitarian response, to plan for an epidemic anywhere? How parallel operations can help in sustaining reliable and quick humanitarian relief response through digitally supported SCs? |

System dynamics Mixed-integer linear programming Socio-technical systems |

| [4][8][23][29][47][76] | Novel and severe disruptions to SCs and how a circular economy can help to sustain production capacities and manage insufficient supply and demand conditions | What are the scenarios that lead to severe ripple effect intensification? Do they cause long-term unremitting bullwhip effects? How can a circular and digitally supported economy help to reduce global shortages and mitigate the effects on production and global supply? |

System dynamics Complexity theory Agent-based simulation Discrete event simulation Informational processing theory |

| [53][72][81][82] | Severe effects on the ecology of epidemic outbreaks in SCs | How to restore and take benefit from severely impacted SCs in a societal and organizational context? How can the focus on environmental sustainability be intensified, such as carbon emission reduction, pollution reduction etc. |

Agent-based simulation Discrete event simulation Knowledge-based systems Mixed-integer linear programming |

| [83][84][85][86] | Drastic reduction in the sales of multiple industrial business and global SCs, and coping with the shortages of medical supplies; building resilient capabilities to repurpose operations during disruptions | How can disruptions to global SCs sales affect short- and long-term goals? How can resilience strategies help in this situation? How can immediate transition and repurposing of factories make it possible to meet novel demands? |

System dynamics Discrete event simulation Contingency theory Digital twinning |

| [30][87][88][89] | Delocalization of manufacturing facilities and reducing the dependence on others | How to reduce dependence and build inhouse capabilities for manufacturing effectively? What are the potential effects on economies because of relocating major manufacturing facilities? |

System dynamics Discrete event simulation Contingency theory |

| [44][90][91][92] | Blockchain as an aid to reduce disruption effects through effective information flow | How blockchain technologies, such as traceability through visibility and security can help to reduce the shortages? How can this help in quickly responding to the disruption? |

Complexity theory Reliability theory Dynamic capabilities Convex programming Mixed-integer linear programming |

| [22][43][93][94][74][95][96][97][98] | Artificial intelligence and additive manufacturing to support SCs during epidemic outbreaks | How artificial intelligence can help industries through digital manufacturing and other assistive technologies in the epoch of epidemics? How can artificial intelligence help in making responsive models, and by providing an optimized strategy through heuristics? How to make an assessment of technological readiness, and roadmap the transformation journey to combat future disruptions? How additive manufacturing assistance with artificial intelligence can repurpose manufacturing demand through digital as well as social media data analytics? How can additive manufacturing contribute to meet urgent demand, such as surgical masks, protective equipment, and so on? |

System dynamics Discrete event simulation Organizational resilience Complexity theory Heuristics Machine/Deep learning-based models |

Initially, the categorization of major epidemic outbreaks which disturbed SCs significantly was carried out. The potential research objectives which were addressed are displayed in Table 1, and the possible solution methodologies were extracted to make a roadmap for the journey of the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, different SC survivability aspects were explored from previous practices in the context of pandemic disruptions, and making resilience a goal for the whole SC network, system, organization, and process, as reported from Table 1. To make SCs ready for future disruptions certain critical components of SCs were extracted, such as resilience and robustness, sustainability and survivability, digitalization, and industry 4.0. All these components play a crucial role during pandemics and are interrelated, such as in the aspects of readiness, vigilance, responsiveness, and preparedness for effective recovery from the disruptions caused by epidemics.

Various governments have been establishing uncommon collaborative activities with manufacturing firms and specific suppliers for the reconfiguration, adaption, and ramping-up of production to provide medical facilities to ensure resilience and flexibility in systems [99][100][101]; this may partially be achieved through digitalization [100][101][102][103][104][105][106][107][108]. Moreover, numerous global societies need to tackle the mismatch between supply and demand in distinct ways, providing social distancing and other cautionary measures [109]. In addition to this, the use of collaborative robots for reconfiguration of existing production setups can be foreseen to enhance the flexibility of a system; for instance, adapting automotive industry for the production of ventilators [99][101]. This could be a future research and development direction to deal with pandemics and large-scale disasters [109]. An exponential growth in research and development in this direction could be seen in the near future [109].

References

- Cao, C.; Li, C.; Yang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Qu, T. A novel multi-objective programming model of relief distribution for sustainable disaster supply chain in large-scale natural disasters. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 1422–1435.

- Andalib Ardakani, D.; Soltanmohammadi, A. Investigating and analysing the factors affecting the development of sustainable supply chain model in the industrial sectors. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 199–212.

- Eskandari-Khanghahi, M.; Tavakkoli-Moghaddam, R.; Taleizadeh, A.A.; Amin, S.H. Designing and optimizing a sustainable supply chain network for a blood platelet bank under uncertainty. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2018, 71, 236–250.

- Rabenasolo, B.; Zeng, X. A Risk-Based Multi-criteria Decision Support System for Sustainable Development in the Textile Supply Chain. In Handbook on Decision Making: Vol 2: Risk Management in Decision Making; Lu, J., Jain, L.C., Zhang, G., Eds.; Intelligent Systems Reference Library; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 151–170. ISBN 978-3-642-25755-1.

- van Barneveld, K.; Quinlan, M.; Kriesler, P.; Junor, A.; Baum, F.; Chowdhury, A.; Junankar, P.N.; Clibborn, S.; Flanagan, F.; Wright, C.F. The COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons on building more equal and sustainable societies. Econ. Labour Relat. Rev. 2020, 31, 133–157.

- Yadav, D.K.; Barve, A. Modeling post-disaster challenges of humanitarian supply chains: A TISM approach. Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2016, 17, 321–340.

- Boostani, A.; Jolai, F.; Bozorgi-Amiri, A. Designing a sustainable humanitarian relief logistics model in pre- and postdisaster management. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2020, 1–17.

- Laguna-Salvadó, L.; Lauras, M.; Okongwu, U.; Comes, T. A multicriteria Master Planning DSS for a sustainable humanitarian supply chain. Ann. Oper. Res. 2019, 283, 1303–1343.

- Peretti, U.; Tatham, P.; Wu, Y.; Sgarbossa, F. Reverse logistics in humanitarian operations: Challenges and opportunities. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain Manag. 2015, 5, 253–274.

- Yu, K.D.S.; Aviso, K.B. Modelling the economic impact and ripple effects of disease outbreaks. Process Integr. Optim. Sustain. 2020, 4, 183–186.

- Fernandes, N. Economic Effects of Coronavirus Outbreak (COVID-19) on the World Economy. Available online: (accessed on 23 February 2021).

- Ivanov, D.; Das, A. Coronavirus (COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2) and supply chain resilience: A research note. Int. J. Integr. Supply Manag. 2020, 13, 90–102.

- Business Insider Coronavirus Business & Economy Impact News | Business Insider. Available online: (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Queiroz, M.M.; Ivanov, D.; Dolgui, A.; Wamba, S.F. Impacts of epidemic outbreaks on supply chains: Mapping a research agenda amid the COVID-19 pandemic through a structured literature review. Ann. Oper. Res. 2020, 1–38.

- de Oliveira, F.N.; Leiras, A.; Ceryno, P. Environmental risk management in supply chains: A taxonomy, a framework and future research avenues. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 1257–1271.

- Mishra, S.; Singh, S.P. A stochastic disaster-resilient and sustainable reverse logistics model in big data environment. Ann. Oper. Res. 2020, 1–32.

- Zarei, M.H.; Carrasco-Gallego, R.; Ronchi, S. To Greener Pastures: An Action Research Study on the Environmental Sustainability of Humanitarian Supply Chains. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2019, 39, 1193–1225.

- Ivanov, D. Revealing interfaces of supply chain resilience and sustainability: A simulation study. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 3507–3523.

- Kaur, H.; Singh, S.P. Sustainable procurement and logistics for disaster resilient supply chain. Ann. Oper. Res. 2019, 283, 309–354.

- Connelly, E.B.; Lambert, J.H.; Thekdi, S.A. Robust investments in humanitarian logistics and supply chains for disaster resilience and sustainable communities. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2016, 17, 04015017.

- Vargas, J.; González, D. Model to assess supply chain resilience. Int. J. Saf. Secur. Eng. 2016, 6, 282–292.

- Forbes the COVID-19 Problems That will Force Manufacturing to Innovate. Available online: (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Shepard, W. COVID-19 Undermines China’s Run as the World’s Factory, but Beijing has a Plan. Available online: (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Settanni, E. Those who do not move, do not notice their (supply) chains—Inconvenient lessons from disruptions related to COVID-19. Ai Soc. 2020, 35, 1065–1071.

- Liu, Y.; Lee, J.M.; Lee, C. The challenges and opportunities of a global health crisis: The management and business implications of COVID-19 from an Asian perspective. Asian Bus. Manag. 2020, 19, 277–297.

- Ivanov, D.; Dolgui, A. A digital supply chain twin for managing the disruption risks and resilience in the era of Industry 4.0. Prod. Plan. Control 2020, 1–14.

- Shamsi G., N.; Ali Torabi, S.; Shakouri G., H. An option contract for vaccine procurement using the SIR epidemic model. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 267, 1122–1140.

- Quayson, M.; Bai, C.; Osei, V. Digital Inclusion for Resilient Post-COVID-19 Supply Chains: Smallholder Farmer Perspectives. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2020, 48, 104–110.

- Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Bryde, D.J.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Papadopoulos, T. Blockchain technology for enhancing swift-trust, collaboration and resilience within a humanitarian supply chain setting. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 3381–3398.

- Ivanov, D. Viable supply chain model: Integrating agility, resilience and sustainability perspectives—Lessons from and thinking beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann. Oper. Res. 2020, 1–21.

- Dolgui, A.; Ivanov, D.; Sokolov, B. Reconfigurable supply chain: The X-network. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 4138–4163.

- Zhang, F.; Wu, X.; Tang, C.S.; Feng, T.; Dai, Y. Evolution of Operations Management Research: From Managing Flows to Building Capabilities. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2020, 29, 2219–2229.

- Kaur, H. Modelling internet of things driven sustainable food security system. Benchmarking Int. J. 2019.

- Beltagui, A.; Kunz, N.; Gold, S. The role of 3D printing and open design on adoption of socially sustainable supply chain innovation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 221, 107462.

- Bag, S.; Wood, L.C.; Mangla, S.K.; Luthra, S. Procurement 4.0 and its implications on business process performance in a circular economy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 152, 104502.

- Malik, A.A.; Masood, T.; Kousar, R. Repurposing factories with robotics in the face of COVID-19. Sci. Robot. 2020, 5, eabc2782.

- Attaran, M. 3D Printing Role in Filling the Critical Gap in the Medical Supply Chain during COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 2020, 10, 988.

- Ivanov, D.; Das, A. Coronavirus (COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2) and supply chain resilience: A research note. Int. J. Integr. Supply Manag. 2020, 13, 90–102.

- Ivanov, D.; Dolgui, A. Viability of intertwined supply networks: Extending the supply chain resilience angles towards survivability. A position paper motivated by COVID-19 outbreak. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 2904–2915.

- Paul, S.; Venkateswaran, J. Designing robust policies under deep uncertainty for mitigating epidemics. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 140, 106221.

- Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Zeng, A.Z. Optimal material distribution decisions based on epidemic diffusion rule and stochastic latent period for emergency rescue. Int. J. Math. Oper. Res. 2009, 1, 76–96.

- Einav, S.; Hick, J.L.; Hanfling, D.; Erstad, B.L.; Toner, E.S.; Branson, R.D.; Kanter, R.K.; Kissoon, N.; Dichter, J.R.; Devereaux, A.V. Surge capacity logistics: Care of the critically ill and injured during pandemics and disasters: CHEST consensus statement. Chest 2014, 146, e17S–e43S.

- Bóta, A.; Gardner, L.M.; Khani, A. Identifying critical components of a public transit system for outbreak control. Netw. Spat. Econ. 2017, 17, 1137–1159.

- Tao, Y.; Shea, K.; Ferrari, M. Logistical constraints lead to an intermediate optimum in outbreak response vaccination. PLoS Comput. Boil. 2018, 14, e1006161.

- Shamsi G., N.; Ali Torabi, S.; Shakouri G., H. An option contract for vaccine procurement using the SIR epidemic model. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 267, 1122–1140.

- Habib, M.S.; Asghar, O.; Hussain, A.; Imran, M.; Mughal, M.P.; Sarkar, B. A robust possibilistic programming approach toward animal fat-based biodiesel supply chain network design under uncertain environment. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 122403.

- Habib, M.S.; Sarkar, B. A multi-objective approach to sustainable disaster waste management. Proc. Int. Conf. Ind. Eng. Oper. Manag. 2018, 2018, 1072–1083.

- Habib, M.S.; Lee, Y.H.; Memon, S. Mathematical Models and Information Systems in Humanitarian Supply Chain Management: A Systematic Literature Review. 2015. Available online: (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Queiroz, M.M.; Ivanov, D.; Dolgui, A.; Wamba, S.F. Impacts of epidemic outbreaks on supply chains: Mapping a research agenda amid the COVID-19 pandemic through a structured literature review. Ann. Oper. Res. 2020, 1–38.

- Dasaklis, T.K.; Pappis, C.P.; Rachaniotis, N.P. Epidemics control and logistics operations: A review. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 139, 393–410.

- Andalib Ardakani, D.; Soltanmohammadi, A. Investigating and analysing the factors affecting the development of sustainable supply chain model in the industrial sectors. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 199–212.

- Eskandari-Khanghahi, M.; Tavakkoli-Moghaddam, R.; Taleizadeh, A.A.; Amin, S.H. Designing and optimizing a sustainable supply chain network for a blood platelet bank under uncertainty. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2018, 71, 236–250.

- Rabenasolo, B.; Zeng, X. A Risk-Based Multi-criteria Decision Support System for Sustainable Development in the Textile Supply Chain. In Handbook on Decision Making: Vol 2: Risk Management in Decision Making; Lu, J., Jain, L.C., Zhang, G., Eds.; Intelligent Systems Reference Library; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 151–170. ISBN 978-3-642-25755-1.

- Paul, S.K.; Sarker, R.; Essam, D.; Lee, P.T.-W. A mathematical modelling approach for managing sudden disturbances in a three-tier manufacturing supply chain. Ann. Oper. Res. 2019, 280, 299–335.

- Currie, C.S.; Fowler, J.W.; Kotiadis, K.; Monks, T.; Onggo, B.S.; Robertson, D.A.; Tako, A.A. How simulation modelling can help reduce the impact of COVID-19. J. Simul. 2020, 14, 83–97.

- Pavlov, A.; Ivanov, D.; Werner, F.; Dolgui, A.; Sokolov, B. Integrated detection of disruption scenarios, the ripple effect dispersal and recovery paths in supply chains. Ann. Oper. Res. 2019, 1–23.

- van Barneveld, K.; Quinlan, M.; Kriesler, P.; Junor, A.; Baum, F.; Chowdhury, A.; Junankar, P.N.; Clibborn, S.; Flanagan, F.; Wright, C.F. The COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons on building more equal and sustainable societies. Econ. Labour Relat. Rev. 2020, 31, 133–157.

- Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Bryde, D.J.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Papadopoulos, T. Blockchain technology for enhancing swift-trust, collaboration and resilience within a humanitarian supply chain setting. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 3381–3398.

- Besiou, M.; Van Wassenhove, L.N. Humanitarian operations: A world of opportunity for relevant and impactful research. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2020, 22, 135–145.

- Dubey, R.; Altay, N.; Blome, C. Swift trust and commitment: The missing links for humanitarian supply chain coordination? Ann. Oper. Res. 2019, 283, 159–177.

- Hosseini, S.; Ivanov, D.; Dolgui, A. Review of quantitative methods for supply chain resilience analysis. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2019, 125, 285–307.

- Ivanov, D.; Dolgui, A. A digital supply chain twin for managing the disruption risks and resilience in the era of Industry 4.0. Prod. Plan. Control 2020, 1–14.

- Hosseini, S.; Ivanov, D. Resilience assessment of supply networks with disruption propagation considerations: A Bayesian network approach. Ann. Oper. Res. 2019.

- Choi, T.-M. Innovative “Bring-Service-Near-Your-Home” Operations under Corona-Virus (COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2) Outbreak: Can Logistics Become the Messiah? Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2020, 140, 101961.

- Dolgui, A.; Ivanov, D.; Rozhkov, M. Does the ripple effect influence the bullwhip effect? An integrated analysis of structural and operational dynamics in the supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 1285–1301.

- Dolgui, A.; Ivanov, D.; Potryasaev, S.; Sokolov, B.; Ivanova, M.; Werner, F. Blockchain-oriented dynamic modelling of smart contract design and execution in the supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 2184–2199.

- Reuters. Boeing to Cut 787/777 Production as COVID-19 Hammers Sales. Available online: (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- Reuters. COVID-19 Crushes U.S. Economy in Second Quarter; Rising Virus Cases Loom over Recovery. Available online: (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- Reuters. U.S. Second-Quarter GDP Falls at Steepest Rate since Great Depression. Available online: (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- Ivanov, D. Revealing interfaces of supply chain resilience and sustainability: A simulation study. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 3507–3523.

- Ivanov, D.; Das, A.; Choi, T.-M. New Flexibility Drivers for Manufacturing, Supply Chain and Service Operations; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2018.

- Malik, A.A.; Masood, T.; Kousar, R. Repurposing factories with robotics in the face of COVID-19. Sci. Robot. 2020, 5, eabc2782.

- Attaran, M. 3D Printing Role in Filling the Critical Gap in the Medical Supply Chain during COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 2020, 10, 988.

- Malik, A.A.; Masood, T.; Kousar, R. Reconfiguring and ramping-up ventilator production in the face of COVID-19: Can robots help? J. Manuf. Syst. 2020, in press.

- Malik, A.A.; Masood, T.; Bilberg, A. Virtual reality in manufacturing: Immersive and collaborative artificial- reality in design of human-robot workspace. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2020, 33, 22–37.

- Elluru, S.; Gupta, H.; Kaur, H.; Singh, S.P. Proactive and reactive models for disaster resilient supply chain. Ann. Oper. Res. 2019, 283, 199–224.

- Masood, T.; Kern, M.; Clarkson, P.J. Characteristics of changeable systems across value chains. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020.

- Egger, J.; Masood, T. Augmented reality in support of intelligent manufacturing—A systematic literature review. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 140, 106195.

- Masood, T.; Sonntag, P. Industry 4.0: Adoption challenges and benefits for SMEs. Comput. Ind. 2020, 121, 103261.

- Masood, T.; Egger, J. Adopting augmented Reality in the age of Industrial Digitalisation. Comput. Ind. 2020, 115, 103112.

- Masood, T.; Egger, J. Augmented reality in support of Industry 4.0—Implementation challenges and success factors. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2019, 58, 181–195.

- Medel, K.; Kousar, R.; Masood, T. A Collaboration–Resilience Framework for Disaster Management Supply Networks: A Case Study of the Philippines. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain Manag. 2020, 10, 509–553.