| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nicolas Le Moigne | + 2057 word(s) | 2057 | 2021-03-08 09:27:44 | | | |

| 2 | Bruce Ren | -125 word(s) | 1932 | 2021-03-16 02:54:21 | | |

Video Upload Options

Several naturally occurring biological systems, such as bones, nacre or wood, display hierarchical architectures with a central role of the nanostructuration that allows reaching amazing properties such as high strength and toughness. Developing such architectures in man-made materials is highly challenging, and recent research relies on this concept of hierarchical structures to design high-performance composite materials. This review deals more specifically with the development of hierarchical fibres by the deposition of nano-objects at their surface to tailor the fibre/matrix interphase in (bio)composites. Fully synthetic hierarchical fibre reinforced composites are described, and the potential of hierarchical fibres is discussed for the development of sustainable biocomposite materials with enhanced structural performance. Based on various surface, microstructural and mechanical characterizations, this review highlights that nano-objects coated on natural fibres (carbon

nanotubes, ZnO nanowires, nanocelluloses) can improve the load transfer and interfacial adhesion between the matrix and the fibres, and the resulting mechanical performances of biocomposites. Indeed, the surface topography of the fibres is modified with higher roughness and specific surface area, implying increased mechanical interlocking with the matrix. As a result, the interfacial shear strength (IFSS) between fibres and polymer matrices is enhanced, and failure mechanisms can be

modified with a crack propagation occurring through a zig-zag path along interphases.

1. Introduction

By combining biopolymers and minerals into hierarchical nanoscaled structures, nature succeeds in developing hybrid materials with amazing mechanical performances such as high strength toughness adapted to the specific needs of biological systems [1]. In this respect, complex biological architectures, displaying self-assembly processes and implying the key role of nanostructuration and nano-objects intrigue researchers and inspire them for the development of innovative engineering materials [2][3][4][5][6][7]. Elaboration of bio-inspired materials has already been investigated in a plethora of engineering materials, mimicking natural systems such as nacre, tooth, bone, or wood [8][9][10][11][12]. Practically, it seems that these architectures modify stress transfer mechanisms within the material and boost their strength and fracture toughness thanks to nanostructuration and the development of a “hierarchical architecture” [13][14][15][16][17]. The hierarchical architecture of a system can be defined as the deployment of structures exhibiting specific organizations at different length scales, going from the macro- to the nanoscale, and ensuring interesting properties to the entire material. This concept has notably been used in composite materials with the implementation of hierarchical fibres via the deposition of nano-objects on fibre surfaces. As an example, the whiskerization of carbon fibres with carbon nanotubes (CNTs) has been developed for the manufacturing of carbon fibre reinforced composites [18][19]. The developed nanostructured composites displayed enhanced mechanical properties due to increased mechanical interlocking and lower local stress concentrations at the fibre/matrix interface, hence resulting in higher strength and toughness [20][21][22][23][24]. Karger-Kocsis et al. (2015) also pointed out the potential of such hierarchical composites for sensing applications, that is, the in-situ sensing of stress, strain, and damage for structural health monitoring [18].

Besides, current environmental issues push towards the implementation of eco-friendly and high-performance composite materials on the market, either hybrid, that is, synthetic/bio-based, or fully bio-based and reinforced with natural fibres and/or bio-based nano-objects [25][26]. In this regard, the development of hierarchical fibres at the interphase zone in (bio)composites is at its very early stage and could be an interesting strategy to tackle current and future challenges raised by the implementation of fully bio-based natural fibre reinforced biocomposites in industrial applications [27][28][29].

2. Naturally Occurring Hierarchical Structures: Towards the Conception of Bio-Inspired Architectures for Composite Materials

2.1. Hierarchical Structures in Biological Systems

The complex architectures found in naturally occurring biological systems are the result of billions of years of evolution with continuous refining of their structure to face different challenges and adapt in an ever-changing environment. They are made of hierarchical micro/nanostructures with soft and organic interfaces (or matrices) and small stiff building blocks. In general, these hierarchical structures include nano-objects, enhancing drastically the mechanical properties, as for instance in bones [30][31], nacre of seashells [32][33], or wood [34].

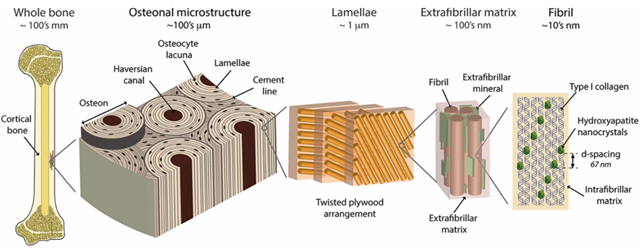

The bone is structured by mineral crystals, that is, hydroxyapatite nanocrystals (thickness 2–4 nm; length up to 100 nm), embedded in a (collagen-rich) protein matrix [35][36], as illustrated in Figure 1. The specific three-dimensional network of hydroxyapatite nanocrystals embedded into collagen fibrils shows peculiar deformation mechanisms that impact positively the mechanical properties of bones. Indeed, collagen fibrils are assembled into collagen fibres, hence forming macroscopic structures such as osteons and lamellae. This hierarchical structure developed over the entire system induces crack deflection and crack bridging mechanisms with impressive properties such as self-healing and adaptation to local stress [37][38][39].

Figure 1. Hierarchical structure of human cortical bone with the presence of hydroxyapatite mineral nanocrystals (reprinted with permission from Zimmermann et al. 2016 [40]).

The nanostructuration plays a central role in the mechanical behaviour of bones. Gao et al. (2003) reported that mineral nanocrystals in natural materials have an optimum size to ensure optimum fracture strength and maximum tolerance of flaws for toughness [41]. Indeed, according to the Griffith criterion, when the mineral size exceeds a critical length of about 30 nm, the fracture strength is sensitive to crack-like flaws and fails by stress concentration. As the mineral platelets size drops below this critical length, the mineral behaves similarly to perfect crystals whatever the type of pre-existing flaws due to accidental soft protein matrix incorporation or defective crystal structure. Considering the bone material, nanometric dimensions of hydroxyapatite crystals and their hierarchical structure thus appears as an optimization for better reinforcement.

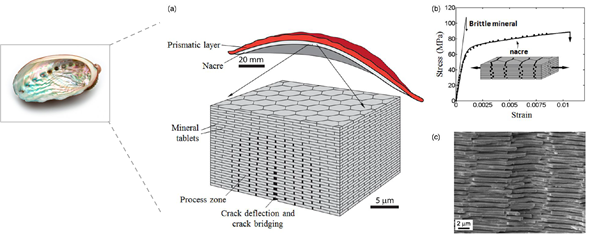

Nacre can be found in the inner layer of mollusc shells (mussels, oysters, etc.) and is made of aragonite plate-like crystals (thickness 200–500 nm; length few micrometres) and a soft matrix of proteins and polysaccharides present in very small amounts [42]. These mineral platelets are structured in a three-dimensional brick wall fashion, as illustrated in Figure 2a. The interfaces between each platelet are soft and very thin (30–40 nm) but seem to play a key role in the toughening mechanisms of mollusc shells. In fact, nacre has a fracture toughness around 3000 times higher than its main component, that is, the aragonite CaCO3 , due to its high deformation capacity when submitted to stress along the direction of the platelets (Figure 2b). A sliding of platelets relative to each other occurs under stress, this phenomenon is driven by the nanostructured interfaces, strengthened by the nano-asperities of the platelets surface, and controlled by the hydration rate [43][44]. Moreover, the crack propagation in nacre is deflected along the interfaces in Figure 2c, which strongly increases the fracture toughness of the material.

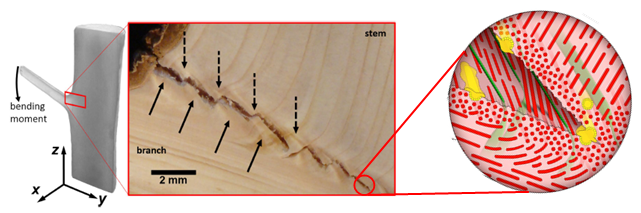

Plant cell walls are the main components of annual plant stems and wood ensuring structural, conducting functions, and protection against pathogens. They are complex composite materials with a hierarchical structure starting from the stem or branch down to the cellulose elementary fibrils/crystallites (thickness 3–5 nm; length 100–1000 nm) associated with various biopolymers as hemicelluloses, lignin and pectins in various amount depending on the species [45]. Müller et al. studied the macroscopic biological interface branch-stem of a Norway spruce in terms of microstructure, and mechanical and self-healing mechanisms. As illustrated in Figure 3, they observed during the bending and breakage of the branch, the occurrence of a zig-zag crack propagation path with crack bridging at the branch-stem interface. This zig-zag shape of cracks has also been observed in natural materials like nacre and bone and requires much more energy for the formation and extension of cracks [46]. This crack pattern is the consequence of the complex and optimized hierarchical interface branch-stem with multiple length scales. At the nanometric scale, the cell orientation and the microfibrillar angle (MFA) of cellulose microfibrils within plant cell walls are perfectly adjusted in tissues of the branch and stem to ensure high flexibility and strength. Moreover, the distribution of cells appears to be adapted to the local damages that could occur at the branch-stem interface, by limiting local stress concentrations.

Figure 2. Nacre from mollusc shell (a) three-dimensional nanostructure of nacre organized in brick wall fashion, (b) tensile stress-strain curves for pure aragonite and nacre, (c) SEM image of the fracture surface of nacre with crack propagation deflected along the interfaces (reprinted with permission from Barthelat et al. 2015).

Figure 3. Zig-zag cracking of branch-stem interface with the model (insert) of the crack propagation in the sacrificial tissue. Wood rays (green) reinforced with tracheids (red) form tissue bundles responsible for crack bridging. High concentration of resin ducts (yellow) activated after the cracking ensures antimicrobial and hydrophobic protection. (reprinted with permission from Müller et al. 2015).

The description of naturally occurring hierarchical architectures and their behaviour under stress can thus be a model for the structuration of interfaces in man-made composite materials based on hierarchical structure concepts using nano-objects. The next section will focus on the conception of hierarchical fibre reinforced composite materials implying the use of nano-objects, as observed in the biological systems presented previously. The creation of such hierarchical composites targets the enhancement of the fibre/matrix interfacial adhesion, a key parameter for stress transfer in composite materials.

2.2. Towards the Conception of Hierarchical Composite Materials Using Nano-Objects

Fibre-reinforced polymer composites are commonly used in many daily life applications and consist of at least three phases: the polymer matrix (thermoplastic, thermoset), the reinforcing fibres (glass, carbon, natural fibres, etc.) and interfacial zones in between, also called interphases since they develop over a certain thickness from the bulk of the matrix to the fibres. The matrix protects reinforcing fibres and achieves the distribution of loads to the fibres and among fibres through the interphases when the composite is submitted to mechanical solicitations [47]. The mechanical properties of the composite such as strength and stiffness are primarily determined by the reinforcement characteristics (intrinsic mechanical properties, volume fraction, orientation, L/d aspect ratio, i.e., L is the fibre length and d corresponds to the fibre lateral dimensions), but the characteristics of the interphases also appear as a key. Indeed, this three-dimensional region between the fibres and the matrix can ensure the load transfer from the matrix to the fibres, provided that the fibre/matrix interfacial adhesion is good enough. Thereby, the bonding strength at the interface largely influences the final properties of the composite, and the role of the interfacial adhesion on their structural integrity is now commonly accepted.

One of the main challenges when developing composite materials is precisely to combine strength and toughness [48]. In general, a strong fibre/matrix interfacial adhesion will achieve high strength and stiffness, while a weaker interfacial adhesion or flexible interphase could enhance toughness performance. Interestingly, structural natural materials such as bones, shells and plant stems seem to succeed in gathering these mechanical properties often antagonistic, and it appears that the combination of soft and stiff components inside the systems, in optimized architectures and concentrations, could be the key for such reinforcement [49]. Moreover, considering the three examples of biological systems described above, the presence of nano-objects within the structure is likely to reinforce the most vulnerable parts of the system undergoing higher stress levels [41]. By now, if we transpose all these observations of natural materials to synthetic and man-made composite materials, the concept of hierarchical architecture appears as an attractive strategy to tailor the fibre/matrix interphase zone, and so increase the strength and toughness and hamper crack propagation within composites.

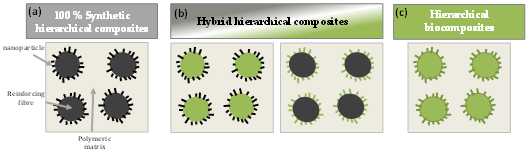

The following sections will focus on the different types of hierarchically nanostructured fibre reinforced composites as schematized in Figure 4, the matrix being either oil-based or bio-based.

Figure 4. Schematic structures of the different hierarchically nanostructured fibre reinforced composites with: (a) fully synthetic hierarchical composites, (b) hybrid hierarchical composites either reinforced with bio-based nanoparticle modified synthetic fibres or with synthetic or mineral nanoparticle modified natural fibres; and (c) hierarchical biocomposites reinforced with bio-based nanoparticle modified natural fibres. Green colour stands for bio-based (nano-)reinforcements and black colour stands for synthetic (nano-)reinforcements.

References

- Barthelat, F.; Rabiei, R.; Dastjerdi, A.K. Multiscale Toughness Amplification in Natural Composites. Mrs Online Proc. Libr. Arch. 2012, 1420, doi:10.1557/opl.2012.714.

- Libonati, F.; Buehler, M.J. Advanced Structural Materials by Bioinspiration. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2017, 19, 1600787, doi:10.1002/adem.201600787.

- Malakooti, M.H.; Zhou, Z.; Spears, J.H.; Shankwitz, T.J.; Sodano, H.A. Biomimetic Nanostructured Interfaces for Hierarchical Composites. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 3, 1500404, doi:10.1002/admi.201500404.

- Barthelat, F. Architectured Materials in Engineering and Biology: Fabrication, Structure, Mechanics and Performance. Int. Mater. Rev. 2015, 60, 413–430, doi:10.1179/1743280415Y.0000000008.

- Wegst, U.G.K.; Bai, H.; Saiz, E.; Tomsia, A.P.; Ritchie, R.O. Bioinspired Structural Materials. Nat. Mater. 2015, 14, 23–36, doi:10.1038/nmat4089.

- Studart, A.R. Biological and Bioinspired Composites with Spatially Tunable Heterogeneous Architectures. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 4423–4436, doi:10.1002/adfm.201300340.

- Sanchez, C.; Arribart, H.; Giraud Guille, M.M. Biomimetism and Bioinspiration as Tools for the Design of Innovative Materials and Systems. Nat. Mater. 2005, 4, 277–288, doi:10.1038/nmat1339.

- Li, M.; Miao, Y.; Zhai, X.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jian, Z.; Wang, X.; Sun, L.; Liu, Z. Preparation of and Research on Bioinspired Graphene Oxide/Nanocellulose/Polydopamine Ternary Artificial Nacre. Mater. Des. 2019, 181, 107961, doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2019.107961.

- Duan, J.; Gong, S.; Gao, Y.; Xie, X.; Jiang, L.; Cheng, Q. Bioinspired Ternary Artificial Nacre Nanocomposites Based on Reduced Graphene Oxide and Nanofibrillar Cellulose. Acs Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 10545–10550, doi:10.1021/acsami.6b02156.

- Dimas, L.S.; Buehler, M.J. Influence of Geometry on Mechanical Properties of Bio-Inspired Silica-Based Hierarchical Materials. Bioinspir. Biomim. 2012, 7, 036024, doi:10.1088/1748-3182/7/3/036024.

- Du, J.; Niu, X.; Rahbar, N.; Soboyejo, W. Bio-Inspired Dental Multilayers: Effects of Layer Architecture on the Contact-Induced Deformation. Acta Biomater. 2013, 9, 5273–5279, doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2012.08.034.

- Opdenbosch, D.V.; Fritz-Popovski, G.; Paris, O.; Zollfrank, C. Silica Replication of the Hierarchical Structure of Wood with Nanometer Precision. J. Mater. Res. 2011, 26, 1193–1202, doi:10.1557/jmr.2011.98.

- Gupta, H.S.; Seto, J.; Wagermaier, W.; Zaslansky, P.; Boesecke, P.; Fratzl, P. Cooperative Deformation of Mineral and Collagen in Bone at the Nanoscale. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 17741–17746, doi:10.1073/pnas.0604237103.

- Weiner, S.; Wagner, H.D. The Material Bone: Structure-Mechanical Function Relations. Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 1998, 28, 271–298, doi:10.1146/annurev.matsci.28.1.271.

- Müller, U.; Gindl-Altmutter, W.; Konnerth, J.; Maier, G.A.; Keckes, J. Synergy of Multi-Scale Toughening and Protective Mechanisms at Hierarchical Branch-Stem Interfaces. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 1–9, doi:10.1038/srep14522.

- Ehlert, G.J.; Galan, U.; Sodano, H.A. Role of Surface Chemistry in Adhesion between ZnO Nanowires and Carbon Fibers in Hybrid Composites. Acs Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 635–645, doi:10.1021/am302060v.

- Galan, U.; Lin, Y.; Ehlert, G.J.; Sodano, H.A. Effect of ZnO Nanowire Morphology on the Interfacial Strength of Nanowire Coated Carbon Fibers. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2011, 71, 946–954, doi:10.1016/j.compscitech.2011.02.010.

- Karger-Kocsis, J.; Mahmood, H.; Pegoretti, A. Recent Advances in Fiber/Matrix Interphase Engineering for Polymer Composites. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2015, 73, 1–43, doi:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2015.02.003.

- Karger-Kocsis, J.; Mahmood, H.; Pegoretti, A. All-Carbon Multi-Scale and Hierarchical Fibers and Related Structural Composites: A Review. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2020, 186, 107932, doi:10.1016/j.compscitech.2019.107932.

- Sharma, M.; Gao, S.; Mäder, E.; Sharma, H.; Wei, L.Y.; Bijwe, J. Carbon Fiber Surfaces and Composite Interphases. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2014, 102, 35–50, doi:10.1016/j.compscitech.2014.07.005.

- Chen, L.; Jin, H.; Xu, Z.; Li, J.; Guo, Q.; Shan, M.; Yang, C.; Wang, Z.; Mai, W.; Cheng, B. Role of a Gradient Interface Layer in Interfacial Enhancement of Carbon Fiber/Epoxy Hierarchical Composites. J. Mater. Sci. 2015, 50, 112–121, doi:10.1007/s10853-014-8571-y.

- Garcia, E.J.; Wardle, B.L.; John Hart, A.; Yamamoto, N. Fabrication and Multifunctional Properties of a Hybrid Laminate with Aligned Carbon Nanotubes Grown In Situ. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2008, 68, 2034–2041, doi:10.1016/j.compscitech.2008.02.028.

- Kepple, K.L.; Sanborn, G.P.; Lacasse, P.A.; Gruenberg, K.M.; Ready, W.J. Improved Fracture Toughness of Carbon Fiber Composite Functionalized with Multi Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Carbon 2008, 46, 2026–2033, doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2008.08.010.

- Wang, W.X.; Takao, Y.; Matsubara, T.; Kim, H.S. Improvement of the Interlaminar Fracture Toughness of Composite Laminates by Whisker Reinforced Interlamination. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2002, 62, 767–774, doi:10.1016/S0266-3538(02)00052-0.

- Idumah, C.I.; Hassan, A. Emerging Trends in Eco-Compliant, Synergistic, and Hybrid Assembling of Multifunctional Polymeric Bionanocomposites. Rev. Chem. Eng. 2016, 32, 305–361, doi:10.1515/revce-2015-0046.

- Saba, N.; Jawaid, M.; Asim, M. Recent advances in nanoclay/natural fibers hybrid composites. In Nanoclay Reinforced Polymer Composites: Natural Fibre/Nanoclay Hybrid Composites; Jawaid, M., Qaiss, A. el K., Bouhfid, R., Eds.; Engineering Materials; Springer: Singapore, 2016; pp. 1–28, ISBN 978-981-10-0950-1.

- Lee, K.-Y.; Delille, A.; Bismarck, A. Greener surface treatments of natural fibres for the production of renewable composite materials. In Cellulose Fibers: Bio- and Nano-Polymer Composites; Kalia, S., Kaith, B.S., Kaur, I., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 155–178, ISBN 978-3-642-17369-1.

- Pommet, M.; Juntaro, J.; Heng, J.Y.Y.; Mantalaris, A.; Lee, A.F.; Wilson, K.; Kalinka, G.; Shaffer, M.S.P.; Bismarck, A. Surface Modification of Natural Fibers Using Bacteria: Depositing Bacterial Cellulose onto Natural Fibers To Create Hierarchical Fiber Reinforced Nanocomposites. Biomacromolecules 2008, 9, 1643–1651, doi:10.1021/bm800169g.

- Dai, D.; Fan, M. Green Modification of Natural Fibres with Nanocellulose. Rsc Adv. 2013, 3, 4659, doi:10.1039/c3ra22196b.

- Rho, J.-Y.; Kuhn-Spearing, L.; Zioupos, P. Mechanical Properties and the Hierarchical Structure of Bone. Med Eng. Phys. 1998, 20, 92–102, doi:10.1016/S1350-4533(98)00007-1.

- Weiner, S.; Traub, W.; Wagner, H.D. Lamellar Bone: Structure—Function Relations. J. Struct. Biol. 1999, 126, 241–255, doi:10.1006/jsbi.1999.4107.

- Kamat, S.; Su, X.; Ballarini, R.; Heuer, A.H. Structural Basis for the Fracture Toughness of the Shell of the Conch Strombus Gigas. Nature 2000, 405, 1036–1040, doi:10.1038/35016535.

- Jackson, A.P.; Vincent, J.F.V.; Turner, R.M.; Alexander, R.M. The Mechanical Design of Nacre. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 1988, 234, 415–440, doi:10.1098/rspb.1988.0056.

- Gershon, A.L.; Bruck, H.A.; Xu, S.; Sutton, M.A.; Tiwari, V. Multiscale Mechanical and Structural Characterizations of Palmetto Wood for Bio-Inspired Hierarchically Structured Polymer Composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2010, 30, 235–244, doi:10.1016/j.msec.2009.10.004.

- Landis, W.J. The Strength of a Calcified Tissue Depends in Part on the Molecular Structure and Organization of Its Constituent Mineral Crystals in Their Organic Matrix. Bone 1995, 16, 533–544, doi:10.1016/8756-3282(95)00076-P.

- Roschger, P.; Grabner, B.M.; Rinnerthaler, S.; Tesch, W.; Kneissel, M.; Berzlanovich, A.; Klaushofer, K.; Fratzl, P. Structural Development of the Mineralized Tissue in the Human L4 Vertebral Body. J. Struct. Biol. 2001, 136, 126–136, doi:10.1006/jsbi.2001.4427.

- Launey, M.E.; Buehler, M.J.; Ritchie, R.O. On the Mechanistic Origins of Toughness in Bone. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2010, 40, 25–53, doi:10.1146/annurev-matsci-070909-104427.

- Peterlik, H.; Roschger, P.; Klaushofer, K.; Fratzl, P. From Brittle to Ductile Fracture of Bone. Nat. Mater. 2006, 5, 52–55, doi:10.1038/nmat1545.

- Nalla, R.K.; Kruzic, J.J.; Kinney, J.H.; Ritchie, R.O. Mechanistic Aspects of Fracture and R-Curve Behavior in Human Cortical Bone. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 217–231, doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.02.017.

- Zimmermann, E.A.; Schaible, E.; Gludovatz, B.; Schmidt, F.N.; Riedel, C.; Krause, M.; Vettorazzi, E.; Acevedo, C.; Hahn, M.; Püschel, K.; et al. Intrinsic Mechanical Behavior of Femoral Cortical Bone in Young, Osteoporotic and Bisphosphonate-Treated Individuals in Low- and High Energy Fracture Conditions. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21072, doi:10.1038/srep21072.

- Gao, H.; Ji, B.; Jager, I.L.; Arzt, E.; Fratzl, P. Materials Become Insensitive to Flaws at Nanoscale: Lessons from Nature. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 5597–5600, doi:10.1073/pnas.0631609100.

- Menig, R.; Meyers, M.H.; Meyers, M.A.; Vecchio, K.S. Quasi-Static and Dynamic Mechanical Response of Haliotis Rufescens (Abalone) Shells. Acta Mater. 2000, 48, 2383–2398, doi:10.1016/S1359-6454(99)00443-7.

- Wang, R.Z.; Suo, Z.; Evans, A.G.; Yao, N.; Aksay, I.A. Deformation Mechanisms in Nacre. J. Mater. Res. 2001, 16, 2485–2493, doi:10.1557/JMR.2001.0340.

- Song, F.; Bai, Y.L. Effects of Nanostructures on the Fracture Strength of the Interfaces in Nacre. J. Mater. Res. 2003, 18, 1741–1744, doi:10.1557/JMR.2003.0239.

- Dufresne, A. Nanocellulose: From Nature to High Performance Tailored Materials; Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG: Berlin, Germany, 2017; ISBN 978-3-11-048041-2.

- Meyers, M.A.; Chen, P.-Y.; Lin, A.Y.-M.; Seki, Y. Biological Materials: Structure and Mechanical Properties. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2008, 53, 1–206, doi:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2007.05.002.

- Le Moigne, N.; Otazaghine, B.; Corn, S.; Angellier-Coussy, H.; Bergeret, A. Surfaces and Interfaces in Natural Fibre Reinforced Composites; SpringerBriefs in Molecular Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-71409-7.

- Ritchie, R.O. The Conflicts between Strength and Toughness. Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 817–822, doi:10.1038/nmat3115.

- Mann, S. Biomineralization: Principles and Concepts in Bioinorganic Materials Chemistry; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001; ISBN 978-0-19-850882-3.