| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cory Brunton | + 1729 word(s) | 1729 | 2021-02-17 22:08:01 |

Video Upload Options

Widespread transmission of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection has resulted in a global COVID-19 pandemic that is straining medical resources worldwide. In the United States (US), hospitals and clinics are challenged to accommodate surging patient populations and care needs while preventing further infection spread. Under such conditions, meeting with patients via telehealth technology is a practical way to help maintain meaningful contact while mitigating SARS-CoV-2 transmission. The application of telehealth to nutrition care can, in turn, contribute to better outcomes and lower burdens on healthcare resources.

To identify trends in telehealth nutrition care before and during the pandemic, we emailed a 20-question, qualitative structured survey to approximately 200 registered dietitian nutritionists (RDNs) from hospitals and clinics that have participated in the Malnutrition Quality Improvement Initiative (MQii). RDN respondents reported increased use of telehealth-based care for nutritionally at-risk patients during the pandemic. They suggested that use of such telehealth nutrition programs supported positive patient outcomes, and some of their sites planned to continue the telehealth-based nutrition visits in post-pandemic care.

Nutrition care by telehealth technology has the potential to improve care provided by practicing RDNs, such as by reducing no-show rates and increasing retention as well as improving health outcomes for patients. We therefore call on healthcare professionals and legislative leaders to implement policy and funding changes that will support improved access to nutrition care via telehealth.

Introduction

The ongoing severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) outbreak has triggered the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and caused a significant strain on medical institutions, particularly in the acute care setting. This disruption of healthcare services has multiple contributing factors: limited availability of adequate personal protective equipment (PPE), the need for defined populations to stay at home, and the high risk of infection spread among patients and healthcare professionals at care sites[1]. In order to follow the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines on social distancing and limited group gatherings[2][3], adoption of telehealth—including telemedicine—has increased rapidly[4].

While the terms “telemedicine” and “telehealth” are sometimes used interchangeably[5], our paper distinguishes between them in several ways. Telemedicine refers to the use of technologies and telecommunication systems to provide clinical healthcare services to patients who are geographically separated from providers. For example, this could involve use of an Electronic Intensive Care Unit (eICU) or Tele-ICU, through which remote intensivists diagnose and treat critical patients in rural areas via technology such as videoconferencing. Telemedicine has facilitated specialty care for patients who live in distant, often rural, locations[6]. Telehealth is a broader term that can refer to clinical as well as non-clinical services. It also applies to the use of electronic information and telecommunications technologies to cover multiple health consultation activities—health monitoring and services, public health and health administration activities, and health education for patients and professionals. In this paper, we will refer to telehealth. Telehealth tools include video conferencing, e-mail, mobile or app-enabled technology, and technologies that transmit clinical information (data, image, audio, and video)[7].

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) declared a Public Health Emergency that temporarily relaxed the existing restrictions on telehealth care[8]. For example, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-covered providers may, in good faith, provide telehealth services to patients using remote communication technologies (including commonly used applications such as FaceTime, Facebook Messenger, Google Hangouts, Zoom, or Skype) for telehealth services, even if the application does not fully comply with HIPAA rules[8]. Accordingly, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) also temporarily expanded access to make it easier for people enrolled in Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) to access medical services via telehealth during the pandemic[9]. CMS expansion currently allows use of telehealth services for: i) patients located in their homes but outside of designated rural areas, ii) remote care, even across state lines, iii) care for new or established patients, and iv) billing for telehealth services (video- or audio-only) as if they were provided in-person[8]. With these expansions enabling care during the COVID-19 pandemic, more than 9 million Medicare beneficiaries received a telehealth service between mid-March and mid-June 2020[10]. Notably, telehealth services have also been applied to providing nutrition care for patients[7],[11][12][13]. Based on work with hospitals, clinics, and systems participating in the Malnutrition Quality Improvement Initiative (MQii)[14], we sought to better understand how RDNs were able to care for their patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, with particular focus on the extent to which telehealth services were being used and potential solutions to the barriers that both RDNs and patients faced.

Feedback from the Field

A 20-question survey (see Appendix) was emailed to approximately 200 RDNs whose institutions participate in the Malnutrition Quality Improvement Initiative (MQii). This survey focused on RDN use of telehealth both before and during the pandemic. We received responses from 22 RDNs (19 from RDNs in clinical practice and three from food and nutrition service managers). 20 respondents reported their hospitals are now providing nutrition telehealth services and 2 are not. The 20 RDNs and/or teams currently utilizing telehealth reported using it to provide the following services:

- Nutrition education

- Nutrition counseling

- Nutrition care plan development

- Nutrition assessment

- Recommendations for nutrition supplementation

- Nutrition discharge planning

- Nutrition screening

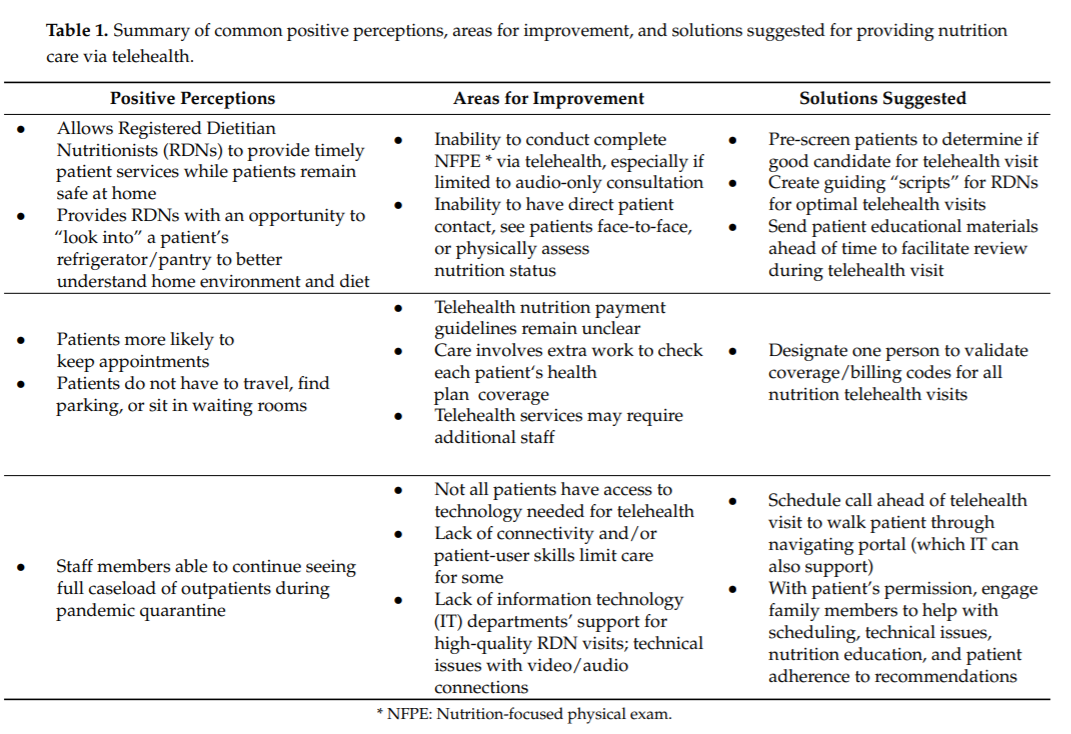

Responses offered insights into positive perceptions, areas for improvement, and potential solutions for future support of nutrition care delivery via telehealth (Table 1). RDN respondents commonly reported that telehealth had positive effects on overall nutrition care in their hospitals/systems and rehab facility. Some reported plans to permanently adopt telehealth for nutrition care after the pandemic is over.

Discussion

While it is too early to know the long-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the US healthcare delivery system, our survey results give us early information about how telehealth can enhance nutrition care. Although the number of our responses was small, we were able to draw on the reported experiences of the MQii Learning Collaborative hospitals and other clinicians to identify opportunities that may help promote quality nutrition care via telehealth and better prepare for future challenges to their practice. The COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 has expedited the adoption of telehealth by many health systems. Information from our survey indicates that telehealth can be an acceptable alternative to in-person clinic and even inpatient visits. In fact, telehealth can enable healthcare providers to maintain usual caseloads and provides patients with uninterrupted healthcare access. Furthermore, telehealth offers opportunities for evaluation and education that might not exist in the face-to-face visit system. For example, telehealth visits have given RDNs the opportunity for longer assessment time with patients and the ability to “look in” their home environments to potentially observe their refrigerators and pantries, allowing further examination of their diet and nutrition habits. In other studies, telenutrition interventions have improved weight loss outcomes in cardiovascular disease patients in a pilot randomized controlled trial[15] and improved weight status in obese patients[16]. Telehealth has specifically been an effective resource for improving diabetes self-management in ethnically diverse and rural populations[17]. A systematic review and meta-analysis reported telenutrition for patients with chronic disease improved diet quality and dietary adherence when compared to face-to-face dietary counseling[18]. Being challenged by a catastrophe such as the COVID-19 pandemic presents an opportunity to create innovative nutrition solutions; telehealth is one of those.

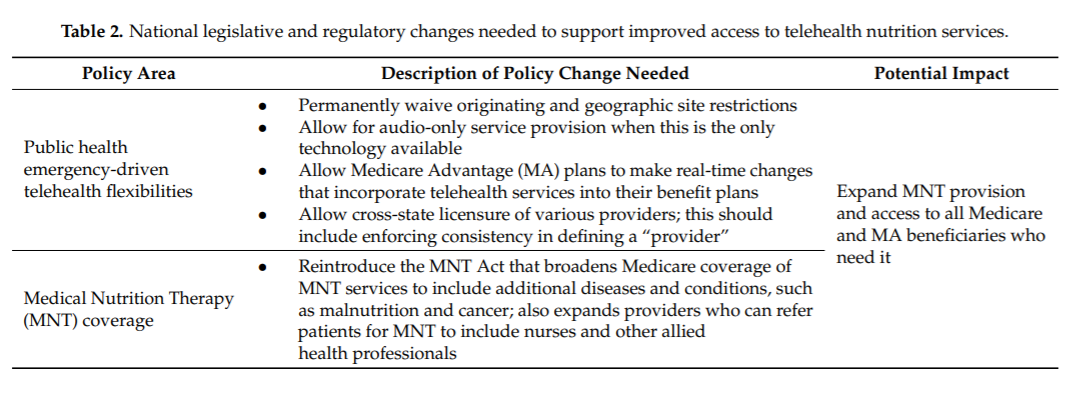

Perhaps the most critical need to continue expanding access to nutrition telehealth services is advocating to policymakers that MNT is essential for comprehensive and effective patient care. Discussions about healthcare reform need to consider all aspects of care that can be delivered effectively through telehealth means both during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Medicare telehealth requirements that existed prior to the pandemic only covered nutrition services via live-video conferencing and under specific circumstances regarding the patient’s and practitioner’s physical locations. With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, CMS has lifted many of these restrictions[8], resulting in an drastic increase in patient telehealth visits[4]. Research from the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine found that 67% of patients surveyed viewed their video and telephone appointments held during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic as “positive and acceptable substitutes to in-person appointments”[19][20]. Our survey respondents reported positive patient experiences related to patients not needing to travel, find parking, sit in waiting rooms, take time off from work or childcare, and/or miss other appointments. It is well documented that the use of telehealth can also improve clinical outcomes, reduce costs[17][21][22], satisfy patients with their nutrition care, and leave individuals with positive perceptions/attitudes[23][24]. Further nutrition-specific research is needed to show such improved outcomes among different patient populations, including the comparison of patients between urban and rural areas. Access to technology—particularly for low-income patients, older patients, and those in rural areas—continues to be a concern for telehealth expansion and could prove a barrier for telenutrition, as well [25]. Changes to healthcare policy should focus on continuing to expand access to telehealth nutrition services by changing payment policies, allowing cross-state licensure of providers, and providing funding to underserved communities to increase their connectivity and access to telehealth services as well as other changes that expand MNT (Table 2).

Recommendations

Our survey respondents reported positive experiences as well as challenges to using telehealth; they also shared recommendations that underscore a need for continued exploration of the patient, provider, economic, and policy implications of telehealth use. It is still unknown how the rapid and drastic switch to telehealth services during the pandemic will affect providers, payers, and patients financially as well as the percentage of visits that will ultimately return to in-person format. To advance health information technology policies and practices, further research should investigate how nutrition services via telehealth compares to other telehealth services as well as how to overcome barriers and identify the best path forward for providing effective and efficient nutrition care. This can ensure the appropriate patients have ready access to the care they need, regardless of where they reside. Continued research should also explore patient preferences and options for improving their reception to telehealth as well as determining the optimal applications and means for integrating with in-person visits for facilitating transitions of care. We call on healthcare professionals and legislative leaders alike to work together to extend policy and payment changes that will support nutrition care provided via telehealth as appropriate throughout and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic.

References

- Bokolo, A. Use of Telemedicine and Virtual Care for Remote Treatment in Response to COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Med. Syst. 2020,44, 1–9

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How to Protect Yourself & Others. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) Personal and Social Activities. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/daily-life-coping/personal-socialactivities.html (accessed on 17 November 2020).

- Doximity Network for Healthcare. 2020 State of Telemedicine Report: Examining Patient Perspectives and Physician Adoption of Telemedicine Since the COVID-19 Pandemic; Doximity: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020.

- NEJM Catalyst. What Is Telehealth? Available online: https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.18.0268 (accessed on 16

- Narva, A.S.; Romancito, G.; Faber, T.; Steele, M.E.; Kempner, K.M. Managing CKD by Telemedicine: The Zuni Telenephrology Clinic. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2017, 24, 6–11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peregrin, T. Telehealth Is Transforming Health Care: What You Need to Know to Practice Telenutrition. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2019,119, 1916–1920. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health and Human Services. Telehealth: Delivering Care Safely during COVID-19. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/coronavirus/telehealth/index.html (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Valladares, A.F.; Kilgore, K.M.; Partridge, J.; Sulo, S.; Kerr, K.W.; McCauley, S. How a Malnutrition Quality Improvement InitiativeFurthers Malnutrition Measurement and Care: Results From a Hospital Learning Collaborative. JPEN J. Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Verma, S. Early Impact of CMS expansion of Medicare Telehealth during COVID-19. Available online: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200715.454789/full/ (accessed on 11 November 2020)

- Mehta, P.; Stahl, M.G.; Germone, M.M.; Nagle, S.; Guigli, R.; Thomas, J.; Shull, M.; Liu, E. Telehealth and Nutrition Support during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Knotowicz, H.; Haas, A.; Coe, S.; Furuta, G.T.; Mehta, P. Opportunities for Innovation and Improved Care Using Telehealth for Nutritional Interventions. Gastroenterology 2019, 157, 594–597. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.T.; Allman-Farinelli, M.; Chen, J.; Partridge, S.R.; Collins, C.; Rollo, M.; Haslam, R.; Diversi, T.; Campbell, K.L. DietitiansAustralia Position Statement on Telehealth. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 77, 406–415.[CrossRef]

- Malnutrition Quality Improvement Initiative. Malnutrition Quality Improvement Initiative (MQii)-Toolkit. Available online: http://malnutritionquality.org/ (accessed on 2 May 2020).

- Ventura Marra, M.; Lilly, C.L.; Nelson, K.R.; Woofter, D.R.; Malone, J. A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of a Telenutrition Weight Loss Intervention in Middle-Aged and Older Men with Multiple Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease. Nutrients 2019, 11, 229.

- Ventura Marra, M.; Shotwell, M.; Nelson, K.R.; Malone, J. Improving weight status in obese middle-aged and older men through telenutrition. Innov. Aging 2017, 1, 635–636.

- Davis, R.M.; Hitch, A.D.; Salaam, M.M.; Herman, W.H.; Zimmer-Galler, I.E.; Mayer-Davis, E.J. TeleHealth Improves Diabetes Self-Management in an Underserved Community: Diabetes TeleCare. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 178–1717.

- Kelly, J.T.; Reidlinger, D.P.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Campbell, K.L. Telehealth methods to deliver dietary interventions in adults with chronic disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 1693–1702.

- Penn Medicine News. Research Shows Patients and Clinicians Rated Telemedicine Care Positively during COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online: https://www.pennmedicine.org/news/newsreleases/2020/june/patientsandcliniciansratedtelemedicinecarepositivelyduringcovi{}:text=After%20reporting%20back%20using%20a,with%20medical%20care%E2%80%9D%20they%20received (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Serper, M.; Nunes, F.; Ahmad, N.; Roberts, D.; Metz, D.C.; Mehta, S.J. Positive Early Patient and Clinician Experience with Telemedicine in an Academic Gastroenterology Practice during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 1589–1591.e4.

- Finkelstein, S.M.; Speedie, S.M.; Potthoff, S. Home Telehealth Improves Clinical Outcomes at Lower Cost for Home Healthcare. Telemed. J. E-Health 2006, 12, 128–136.

- Wade, V.A.; Karnon, J.; Elshaug, A.G.; Hiller, J.E. A Systematic Review of Economic Analyses of Telehealth Services Using Real Time Video Communication. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2010, 10, 233.

- Edinger, J.L. Northeast Ohio Adults’ Perceptions and Attitudes towards the Use of Telenutrition. Ph.D. Thesis, Kent State University, Kent, OH, USA, 2016.

- Warner, M.M.; Tong, A.; Campbell, K.L.; Kelly, J.T. Patients’ Experiences and Perspectives of Telehealth Coaching with a Dietitian to Improve Diet Quality in Chronic Kidney Disease: A Qualitative Interview Study. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 119, 1362–1374.

- Weigel, G.; Ramaswamy, A.; Sobel, L.; Salganicoff, S.; Cubanski, J.; Freed, M. Opportunities and Barriers for Telemedicine in,the U.S. during the COVID-19 Emergency and Beyond. Available online: https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issuebrief/opportunities-and-barriers-for-telemedicine-in-the-u-s-during-the-covid-19-emergency-and-beyond/ (accessed on 2 February 2021).