| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nader Rahimi | + 2389 word(s) | 2389 | 2021-01-07 10:57:25 | | | |

| 2 | Lily Guo | + 75 word(s) | 2464 | 2021-01-13 08:56:58 | | |

Video Upload Options

COVID-19 pandemic continues to pose a serious threat to global public health with overwhelming worldwide socio-economic disruption. SARS-CoV-2, the viral agent of COVID-19, uses its surface glycoprotein Spike (S) for host cell attachment and entry. The emerging picture of pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 demonstrates that S protein, in addition, to ACE2, interacts with the carbohydrate recognition domain (CRD) of C-type lectin receptors, CD209L and CD209. Recognition of CD209L and CD209 which are widely expressed in SARS-CoV-2 target organs can facilitate entry and transmission leading to dysregulation of the host immune response and other major organs including, cardiovascular system. Establishing a comprehensive map of the SARS-CoV-2 interaction with CD209 family proteins, and their roles in transmission and pathogenesis can provide new insights into host-pathogen interaction with implications in therapies and vaccine development.

1. Introduction

Lectins are a diverse family of carbohydrate recognizing proteins that possess carbohydrate-recognition domain (CRD) or sulfated glycosaminoglycan (SGAG)-binding motif [1][2]. Derived from the Latin word “legere”, meaning “to select”. Lectins were originally identified for their selective carbohydrate binding properties. However, now it is known that they can also mediate protein-protein, protein-lipid or protein-nucleic acid interactions[3]. By virtue of their CRD, lectins have the ability to recognize specific carbohydrate structures on proteins, which in turn, mediate cell-cell and cell-pathogen interactions[4][5]. There are currently fourteen structural families and three related subfamilies of lectins in human genome that span 76 different genes [6]. The C-type (calcium-dependent) lectins with 66 gene members is one of the largest subgroups of the lectin superfamily[6][7] that are further separated into multiple subgroups[8][9][10]. One of these subgroups is the CD209/DC-SIGN (Dendritic cell-specific ICAM-3-grabbing non-integrin 1 also called CLEC4L, C-type lectin domain family 4 member L) subgroup, which includes CD209/DC-SIGN (and three other member genes, namely CD209L/L-SIGN/CLEC4M (Liver/lymph node-specific ICAM-3-grabbing non-integrin, C-type lectin domain family 4 member M), CD23 and LSECtin/CLEC4G [11][12]. Mouse genome encodes five homologues of human CD209 with a variable sequence homology to human CD209[13], but it is not clear whether their function is similar to human CD209L and CD209. Other major lectin subfamily proteins are the P-type lectins (mannose 6-phosphate (M6P) and the I-type lectins. Siglecs (Sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-type lectins) are the best characterized I-type lectins [14][15]. Given the role of CD209L and related proteins in diverse mechanisms of pathogen recognition and emerging evidence for the role of CD209 family proteins in SARS-CoV-2 entry and infection[16], this review article particularly has focused on the recent advances in the cellular and biochemical characterization of CD209 and CD209L and their roles in virial uptake, which could provide valuable insights pertinent to current pathobiological studies and therapeutic development of vaccines for SARS-Cov-2.

2. CD209/DC-SIGN and CD209L/L-SIGN Family Proteins: Cell Adhesion Molecules Turned to Pathogen Recognition Receptors:

The conserved physiological function of CD209 family proteins is to mediate cell-cell adhesion by functioning as high affinity receptors for intercellular adhesion molecules 2 and 3 (ICAM2 and ICAM3/ CD50)[17][18]. CD23 acts as a low-affinity receptor for immunoglobulin E (IgE) and CR2/CD21[19] and LSECtin interacts with CD44 on activated T cells [20]. A survey of current literature indicates that these receptors are also among the most common pathogen recognition receptors present in the human genome[21][22]. CD209L and CD209 serve as receptors for Ebolavirus[23], Hepatitis C virus[24], human coronavirus 229E[25], human cytomegalovirus/HHV-5 [26], influenza virus[27], West-Nile virus[26], Dengue virus [28] and Japanese encephalitis virus[29]. Recently, we and others have shown that CD209 and CD209L is capable of recognizing SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 [16][26][30][31]]. In addition to its ability to recognize a plethora of viruses, CD209 is also known to recognize parasites such as leishmania amastigotes [32] and Yersinia pestis coccobacillus bacterium[33]. The complete list of viruses that are recognized by CD209, CD209L and LSECtin are shown (Table 1). To date, it is not known whether CD23 is involved in any pathogen recognition.

Table 1. List of known pathogens recognized by CD209, CD209L and LSECtin lectin family proteins. The data is extracted from the publications available through PubMed.

| Gene Name | Pathogen Name | References |

|---|---|---|

| CD209 | HIV-1 and HIV-2 | [34][35] |

| Ebolavirus | [36][37] | |

| Cytomegalovirus | [24][38] | |

| Hepatitis C virus | [24] | |

| Dengue virus | [28] | |

| Measles virus | [39] | |

| Herpes simplex virus | [40] | |

| Influenza virus A | [27] | |

| SARS-CoV-2 | [16] | |

| SARS-CoV | [30] | |

| MERS | [41] | |

| Japanese encephalitis virus | [29] | |

| Lassa virus | [42] | |

| Respiratory syncytial virus | [43] | |

| Rift valley fever virus | [44] | |

| Uukuniemi virus | [44] | |

| West-Nile virus | [45] | |

| CD209L | Ebolavirus | [23] |

| Hepatitis C virus | [24] | |

| HIV-1 | [37][46] | |

| Human coronavirus 229E | [25] | |

| Human cytomegalovirus/HHV-5 | [47] | |

| Influenza virus | [27] | |

| SARS-CoV | [26] | |

| SARS-CoV-2 | [16] | |

| West-Nile virus | [26] | |

| Japanese encephalitis virus | [29] | |

| Marburg virus | [26] | |

| LSECtin | Japanese encephalitis virus | [12] |

| Ebolavirus | [48] | |

| SARS-CoV | [48] | |

| Lassa virus | [49] |

t is increasingly evident that viruses exploit host lectin receptors like the CD209L family proteins and others for two major reasons; to promote infection of target cells and evade the immune recognition system. In many cases lectin receptors such as CD209 and CD209L are employed as functional portals for viral recognition and infection. However, in some other cases, they may also enable infection of target cells via trans-infection (i.e., cell captures the pathogen without entry and then passes it to another cell, which is also a replication-independent mechanism [50]. For example, CD209 expressed in DCs can bind to HIV envelope glycoprotein, gp120, without triggering cell-virus fusion[51]. The interaction of CD209 with gp120 appears to be complex as it can lead to both positive and negative outcomes for virus, perhaps depending to cell type in which CD209 is expressed. In some cases, CD209-captured virions are internalized and targeted to the lysosome for degradation[52][53]. However, in cases which HIV-1 receptor and co-receptors (CD4 and CCR5/CXCR4) are present on the host cells, CD209 can facilitate infection by transferring the virus to immune cells [54][55]. Additionally, it was found that CD209-dependent capture of HIV-1 virions could transiently protect virions from degradation, which ultimately leads to viral infectivity [56][57][58], suggesting that CD209 positive DCs capture and internalize HIV-1 virions and homes them to lymph nodes[59]. However, the Trojan horse model of HIV transmission by CD209 was challenged by various studies[60]. Studies on B lymphocytes and platelets indicate that CD209 expressed in these cells successfully mediate the entry of and infection by HIV-1[61][62][63]. Similarly, CD209 and CD209L interact with Ebola virus glycoprotein and mediate infection of endothelial cells via both cis- and trans-infection[23][36]. Likewise, the recent findings also support for CD209L-mediated cis- and trans-infection of SARS-CoV-2[16][64]. Aside from the role of CD209 and CD209L in cis- and trans-infection and transmission, the recognition of these receptors by pathogens also can impact the host defense mechanism against these pathogens. For instance, CD209-dependent viral entry and infection can initiate signaling events in host cells that compromise immune responses and promote infection of DCs[65][66]. Interestingly, although CD209L and CD209 are devoid of any enzymatic activity, however upon interaction with pathogens, they can stimulate activation of multiple protein kinases, GTPases and phosphatases[67].

3. CD209/DC-SIGN and CD209L/L-SIGN Family Proteins and Coronaviruses:

The evolutionarily conserved mechanism by which human coronaviruses including, CoV-229E, NL63, OC43, HKU1, MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 recognize the host cells rely on the viral glycoprotein spike (S) that interacts with specific receptors on the host target cells. Intriguingly, the S protein appears to be highly adept and can interact with different types of host receptors. For examples, the S protein of CoV-229E and transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV) employ CD13 (aminopeptidase N) as a receptor for entry and infection of target cells[68][69], whereas S protein of CoV-NL63 and HKU1 interact with glycan-based receptors carrying 9-O-acetylated sialic acid (9-O-Ac-Sia)[70][71]. The S protein of MERS-CoV uses Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4/CD26) and carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 5 (CEACAM5) as attachment or entry receptors for infection[72][73]. CEACAM5 appears to facilitate MERS-CoV infection by enhancing the attachment of the virus to the host cell surface [73]. The S protein of Filoviridae Marburg virus, SARS-CoV [26,31] and SARS-CoV-2[16][74] can employ the carbohydrate-recognition domain (CRD) containing CD209L and CD209 lectins as attachment or entry receptor.

CD209L is broadly expressed in human lung, kidney epithelium and endothelium[16]. Furthermore, human endothelial cells are permissive to SARS-CoV-2 infection and interference with CD209L activity via shRNA or soluble CD209L inhibited SARS-CoV-2 entry and replication[16]. Remarkably, the S protein of human coronaviruses including, NL63[75], SARS-CoV[76] and SARS-CoV-2[16] can also employ angiotensin-converting enzyme 2(ACE2) as an entry receptor for infection, suggesting that both ACE2 and the lectin family proteins, CD209L and CD209, contribute to the spread of these pathogens in vivo. Previous studies on SARS-CoV demonstrated a direct role for CD209L and CD209 in infection by acting as entry receptors for SARS independent of ACE2 [77][78][79][80]. Curiously, CD209L can physically interact with ACE2[16], suggesting both ACE2-dependent and independent mechanisms for CD209L-mediated viral entry. However, the underlying mechanism of CD209L and CD209 mediated SARS-CoV-2 infection is not fully understood and requires further investigation.

4. Topology of CD209L/L-SIGN and CD209/D-SIGN

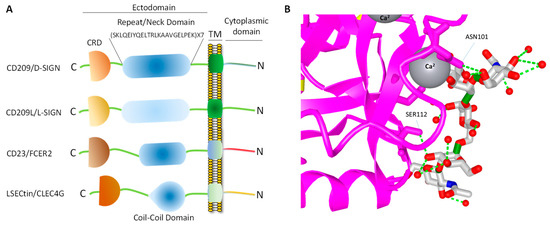

CD209 family proteins are type II transmembrane glycoprotein receptors (i.e., C-terminus is exposed outside the lipid bilayer and N-terminus resides in the cytosol). The ectodomain of CD209 and CD209L is composed of the neck region followed by the CRD. These domains represent the most distinct and functional features of these two receptors (Figure 1A). The neck/repeat region is composed of 23 amino acids which is repeated seven times in CD209L and CD209 and three times in CD23/FCER (Figure 1A). However, the neck/repeat region on LSECtin/CLEC4G is replaced with a coil-coil motif, which is also involved in protein-protein interaction (Figure 1A). Central to recognition of cellular and pathogen glycoproteins, is the presence of the CRD on the C-terminus of CD209 family proteins, which is paramount to recognition of mannose containing structures present on specific glycoproteins.

Figure 1. CD209 family proteins. (A) Graphic presentation of CD209 family proteins and the key domain information. The schematic of domains do not directly correlate to the number of amino acids in each domain. (B) Crystal structure of a typical CRD complexed with carbohydrate and the position of the Ca2+ ion, which makes a tertiary complex between lectin and carbohydrate structure.

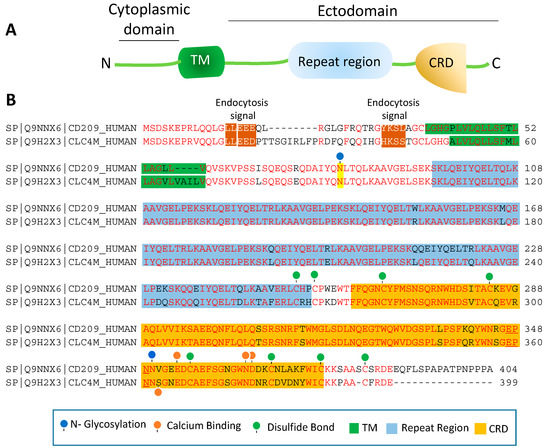

CRD is a 110–130 amino acid long with a double-looped, two-stranded anti-parallel β-sheet connected by two α-helices and a three-stranded anti-parallel β-sheet[81]. Typically, CRD has two conserved disulfide bonds and up to four Ca2+ binding sites, depending on the specific family of lectin. Amino acid residues with the carbonyl side chains are involved in coordinating Ca2+ in the CRD, and these residues also directly bind to carbohydrates leading to a ternary complex formation between a carbohydrate in a glycan, the Ca2+ ion, and amino acids within the CRD. A typical CRD-carbohydrate interaction is shown (Figure 1B). Amino acid sequence alignment of CD209L with CD209 illustrates that these proteins are highly conserved, suggesting that they likely evolved through gene duplications. There are at least two putative internalization motifs at the cytosolic N-terminus tail of CD209 and CD209L, indicating that both CD209 and CD209L upon interaction with pathogens are capable of undergoing internalization and delivering the pathogen inside the target cells. The internalization motifs are di-leucine (LL) and tyrosine(Y)-based (Figure 2B), but, the key tyrosine residue in the tyrosine-based internalization motif on the CD209L is replaced with histidine (H) (Figure 2B), indicating that CD209L undergoes internalization solely via di-leucine motif[82].

Figure 2. Amino acid sequence homology of CD209 and CD209L: (A) The schematic of CD209L is shown. (B) Alignment of the amino acids of human CD209 and CLEC4M (gene encoding for CD209L called C-type lectin domain family 4 member M, CLEC4M). The key common features of CD209L and CD209L, including potential PTMs and ion bindings are highlighted.

The ectodomain of CD209 and CD209L is composed of the neck region followed by the CRD. These domains also represent the most distinct and functional features of these two receptors. The neck region which is a repeat of 23 amino acids (Figure 2B), is involved in protein dimerization/oligomerization[83][84], and may also contribute to increased pathogen recognition and concentration of pathogens at the cell surface. The neck region forms an α-helical coiled-coil fold that is thought to stabilize the oligomerization of CD20 family proteins[85][86]. The presence of CRD on the ectodomain is paramount to recognition of mannose, fucose- or galactose-containing structures on the pathogens and the cellular ligands by CD209 and CD209L. It is thought that within the CRD a highly conserved EPN motif (Glu-Pro-Asn) is responsible for recognition of mannose, fucose- or galactose-containing structures[87]. Yet, despite a high degree of homology of the amino acid residues in the CRD of CD209L and CD209, there is evidence for differential recognition of oligosaccharide structures by these receptors. For example, CD209L appears to prefer mannose oligosaccharides but not fucose-containing carbohydrates such as LewisX (LeX) glycans [88]. Interestingly, a recent analysis revealed that N-glycosylation of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein is largely oligomannose-type glycans[89], which may account for the strong binding of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein with CD209L and CD209[16]. Furthermore, while the ectodomain of CD209L contains two N-glycosylation sequons, at sites N92 and N361 (Figure 2B), only N92 is occupied.

Curiously, removal of N-glycosylation on the CD209L increases the binding of CD209L with the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein[16], suggesting that N-glycosylation of CD209L may generate a hindrance for the CRD-mediated glycoprotein interaction[16] and may have impact in virus tropism and transmissibility in vivo. A similar hindering mechanism for ligand-receptor interaction by N-glycosylation was reported for an unrelated receptor tyrosine kinase, vascular endothelial receptor-2 (VEGFR-2) interaction with its ligand [90]. Another important, yet poorly understood aspect of CD209 family proteins is their cytoplasmic N-terminus domain, which is vital for their signal transduction relays. To date, there is no evidence for potential posttranslational modifications (PTMs) or a direct protein interaction between the cytoplasmic N-terminus domains of CD209L and CD209 with the signaling proteins[67]. Unlike many of their counterpart receptors, the cytoplasmic N-terminus domains of CD209L and CD209 contain no conserved immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory (ITIM, V/IXYXXL/I/V) motif, which interacts with the Src-homology 2 (SH2) domain containing proteins [91]. While, the cytoplasmic N-terminus domains of CD209L contains no tyrosine residue, the cytoplasmic N-terminus domain of CD209 contains one tyrosine residue with a weak sequence homology to ITIM motif (Figure 2B). But, there is no experimental evidence whether the key tyrosine (Y31) residue is phosphorylated and recruits any SH2 domain signaling proteins to CD209. Furthermore, there are multiple serine/threonine residues (four on the CD209 and 8 on the CD209L) on the cytoplasmic N-terminus domains of CD209L and CD209 (Figure 2B), which potentially could be phosphorylated. Similarly, there are multiple lysine (K) residues on the cytoplasmic N-terminus domain of CD209L and CD209 with potential to undergo ubiquitination. In particular, K5, which is conserved both in CD209L and CD209, has a high probability to be ubiquitinated. Ubiquitin modification regulates both proteolytic and non-proteolytic functions of proteins[92].

References

- Mulloy, B.; Linhardt, R.J. Order out of complexity--protein structures that interact with heparin. Current opinion in structural biology 2001, 11, 623-628.

- Esko, J.D.; Selleck, S.B. Order out of chaos: assembly of ligand binding sites in heparan sulfate. Annual review of biochemistry 2002, 71, 435-471.

- Kilpatrick, D.C. Animal lectins: a historical introduction and overview. Biochim Biophys Acta 2002, 1572, 187-197, doi:10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00308-2.

- Van Breedam, W.; Pohlmann, S.; Favoreel, H.W.; de Groot, R.J.; Nauwynck, H.J. Bitter-sweet symphony: glycan-lectin interactions in virus biology. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2014, 38, 598-632.

- Sharon, N.; Lis, H. History of lectins: from hemagglutinins to biological recognition molecules. Glycobiology 2004, 14, 53R-62R.

- Drickamer, K.; Fadden, A.J. Genomic analysis of C-type lectins. Biochemical Society symposium 2002, 59-72.

- Sharon, N.; Lis, H. The structural basis for carbohydrate recognition by lectins. Adv Exp Med Biol 2001, 491, 1-16, doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-1267-7_1.

- Zelensky, A.N.; Gready, J.E. The C-type lectin-like domain superfamily. The FEBS journal 2005, 272, 6179-6217.

- Ebner, S.; Sharon, N.; Ben-Tal, N. Evolutionary analysis reveals collective properties and specificity in the C-type lectin and lectin-like domain superfamily. Proteins 2003, 53, 44-55.

- Drickamer, K.; Taylor, M.E. Recent insights into structures and functions of C-type lectins in the immune system. Current opinion in structural biology 2015, 34, 26-34.

- Soilleux, E.J.; Barten, R.; Trowsdale, J. DC-SIGN; a related gene, DC-SIGNR; and CD23 form a cluster on 19p13. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950) 2000, 165, 2937-2942.

- Liu, W.; Tang, L.; Zhang, G.; Wei, H.; Cui, Y.; Guo, L.; Gou, Z.; Chen, X.; Jiang, D.; Zhu, Y., et al. Characterization of a novel C-type lectin-like gene, LSECtin: demonstration of carbohydrate binding and expression in sinusoidal endothelial cells of liver and lymph node. The Journal of biological chemistry 2004, 279, 18748-18758.

- Park, C.G.; Takahara, K.; Umemoto, E.; Yashima, Y.; Matsubara, K.; Matsuda, Y.; Clausen, B.E.; Inaba, K.; Steinman, R.M. Five mouse homologues of the human dendritic cell C-type lectin, DC-SIGN. Int Immunol 2001, 13, 1283-1290, doi:10.1093/intimm/13.10.1283.

- Crocker, P.R.; Clark, E.A.; Filbin, M.; Gordon, S.; Jones, Y.; Kehrl, J.H.; Kelm, S.; Le Douarin, N.; Powell, L.; Roder, J., et al. Siglecs: a family of sialic-acid binding lectins. Glycobiology 1998, 8, v.

- Varki, A.; Angata, T. Siglecs--the major subfamily of I-type lectins. Glycobiology 2006, 16, 1R-27R.

- Amraie, R.; Napoleon, M.A.; Yin, W.; Berrigan, J.; Suder, E.; Zhao, G.; Olejnik, J.; Gummuluru, S.; Muhlberger, E.; Chitalia, V., et al. CD209L/L-SIGN and CD209/DC-SIGN act as receptors for SARS-CoV-2 and are differentially expressed in lung and kidney epithelial and endothelial cells. bioRxiv : the preprint server for biology 2020.

- Geijtenbeek, T.B.; Torensma, R.; van Vliet, S.J.; van Duijnhoven, G.C.; Adema, G.J.; van Kooyk, Y.; Figdor, C.G. Identification of DC-SIGN, a novel dendritic cell-specific ICAM-3 receptor that supports primary immune responses. Cell 2000, 100, 575-585.

- Bashirova, A.A.; Geijtenbeek, T.B.; van Duijnhoven, G.C.; van Vliet, S.J.; Eilering, J.B.; Martin, M.P.; Wu, L.; Martin, T.D.; Viebig, N.; Knolle, P.A., et al. A dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing nonintegrin (DC-SIGN)-related protein is highly expressed on human liver sinusoidal endothelial cells and promotes HIV-1 infection. J Exp Med 2001, 193, 671-678, doi:10.1084/jem.193.6.671.

- Hibbert, R.G.; Teriete, P.; Grundy, G.J.; Beavil, R.L.; Reljic, R.; Holers, V.M.; Hannan, J.P.; Sutton, B.J.; Gould, H.J.; McDonnell, J.M. The structure of human CD23 and its interactions with IgE and CD21. J Exp Med 2005, 202, 751-760, doi:10.1084/jem.20050811.

- Tang, L.; Yang, J.; Tang, X.; Ying, W.; Qian, X.; He, F. The DC-SIGN family member LSECtin is a novel ligand of CD44 on activated T cells. Eur J Immunol 2010, 40, 1185-1191, doi:10.1002/eji.200939936.

- Kerr, J.R. Cell adhesion molecules in the pathogenesis of and host defence against microbial infection. Mol Pathol 1999, 52, 220-230, doi:10.1136/mp.52.4.220.

- Amraei, R.; Rahimi, N. COVID-19, Renin-Angiotensin System and Endothelial Dysfunction. Cells 2020, 9.

- Alvarez, C.P.; Lasala, F.; Carrillo, J.; Muniz, O.; Corbi, A.L.; Delgado, R. C-type lectins DC-SIGN and L-SIGN mediate cellular entry by Ebola virus in cis and in trans. J Virol 2002, 76, 6841-6844, doi:10.1128/jvi.76.13.6841-6844.2002.

- Cormier, E.G.; Durso, R.J.; Tsamis, F.; Boussemart, L.; Manix, C.; Olson, W.C.; Gardner, J.P.; Dragic, T. L-SIGN (CD209L) and DC-SIGN (CD209) mediate transinfection of liver cells by hepatitis C virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004, 101, 14067-14072, doi:10.1073/pnas.0405695101.

- Jeffers, S.A.; Hemmila, E.M.; Holmes, K.V. Human coronavirus 229E can use CD209L (L-SIGN) to enter cells. Adv Exp Med Biol 2006, 581, 265-269, doi:10.1007/978-0-387-33012-9_44.

- Marzi, A.; Gramberg, T.; Simmons, G.; Moller, P.; Rennekamp, A.J.; Krumbiegel, M.; Geier, M.; Eisemann, J.; Turza, N.; Saunier, B., et al. DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR interact with the glycoprotein of Marburg virus and the S protein of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Virol 2004, 78, 12090-12095, doi:10.1128/JVI.78.21.12090-12095.2004.

- Londrigan, S.L.; Turville, S.G.; Tate, M.D.; Deng, Y.M.; Brooks, A.G.; Reading, P.C. N-linked glycosylation facilitates sialic acid-independent attachment and entry of influenza A viruses into cells expressing DC-SIGN or L-SIGN. J Virol 2011, 85, 2990-3000, doi:10.1128/JVI.01705-10.

- Tassaneetrithep, B.; Burgess, T.H.; Granelli-Piperno, A.; Trumpfheller, C.; Finke, J.; Sun, W.; Eller, M.A.; Pattanapanyasat, K.; Sarasombath, S.; Birx, D.L., et al. DC-SIGN (CD209) mediates dengue virus infection of human dendritic cells. J Exp Med 2003, 197, 823-829, doi:10.1084/jem.20021840.

- Shimojima, M.; Takenouchi, A.; Shimoda, H.; Kimura, N.; Maeda, K. Distinct usage of three C-type lectins by Japanese encephalitis virus: DC-SIGN, DC-SIGNR, and LSECtin. Arch Virol 2014, 159, 2023-2031, doi:10.1007/s00705-014-2042-2.

- Yang, Z.Y.; Huang, Y.; Ganesh, L.; Leung, K.; Kong, W.P.; Schwartz, O.; Subbarao, K.; Nabel, G.J. pH-dependent entry of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus is mediated by the spike glycoprotein and enhanced by dendritic cell transfer through DC-SIGN. J Virol 2004, 78, 5642-5650, doi:10.1128/JVI.78.11.5642-5650.2004.

- Jeffers, S.A.; Tusell, S.M.; Gillim-Ross, L.; Hemmila, E.M.; Achenbach, J.E.; Babcock, G.J.; Thomas, W.D., Jr.; Thackray, L.B.; Young, M.D.; Mason, R.J., et al. CD209L (L-SIGN) is a receptor for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004, 101, 15748-15753, doi:10.1073/pnas.0403812101.

- Colmenares, M.; Puig-Kroger, A.; Pello, O.M.; Corbi, A.L.; Rivas, L. Dendritic cell (DC)-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3 (ICAM-3)-grabbing nonintegrin (DC-SIGN, CD209), a C-type surface lectin in human DCs, is a receptor for Leishmania amastigotes. J Biol Chem 2002, 277, 36766-36769, doi:10.1074/jbc.M205270200.

- Zhang, P.; Skurnik, M.; Zhang, S.S.; Schwartz, O.; Kalyanasundaram, R.; Bulgheresi, S.; He, J.J.; Klena, J.D.; Hinnebusch, B.J.; Chen, T. Human dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule-grabbing nonintegrin (CD209) is a receptor for Yersinia pestis that promotes phagocytosis by dendritic cells. Infect Immun 2008, 76, 2070-2079, doi:10.1128/IAI.01246-07.

- Curtis, B.M.; Scharnowske, S.; Watson, A.J. Sequence and expression of a membrane-associated C-type lectin that exhibits CD4-independent binding of human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein gp120. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1992, 89, 8356-8360.

- Geijtenbeek, T.B.H.; van Duijnhoven, G.C.F.; van Vliet, S.J.; Krieger, E.; Vriend, G.; Figdor, C.G.; van Kooyk, Y. Identification of different binding sites in the dendritic cell-specific receptor DC-SIGN for intercellular adhesion molecule 3 and HIV-1. The Journal of biological chemistry 2002, 277, 11314-11320.

- Simmons, G.; Reeves, J.D.; Grogan, C.C.; Vandenberghe, L.H.; Baribaud, F.; Whitbeck, J.C.; Burke, E.; Buchmeier, M.J.; Soilleux, E.J.; Riley, J.L., et al. DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR bind ebola glycoproteins and enhance infection of macrophages and endothelial cells. Virology 2003, 305, 115-123.

- Lin, G.; Simmons, G.; Pohlmann, S.; Baribaud, F.; Ni, H.; Leslie, G.J.; Haggarty, B.S.; Bates, P.; Weissman, D.; Hoxie, J.A., et al. Differential N-linked glycosylation of human immunodeficiency virus and Ebola virus envelope glycoproteins modulates interactions with DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR. Journal of virology 2003, 77, 1337-1346.

- Cormier, E.G.; Durso, R.J.; Tsamis, F.; Boussemart, L.; Manix, C.; Olson, W.C.; Gardner, J.P.; Dragic, T. L-SIGN (CD209L) and DC-SIGN (CD209) mediate transinfection of liver cells by hepatitis C virus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2004, 101, 14067-14072.

- Lai, W.K.; Sun, P.J.; Zhang, J.; Jennings, A.; Lalor, P.F.; Hubscher, S.; McKeating, J.A.; Adams, D.H. Expression of DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR on human sinusoidal endothelium: a role for capturing hepatitis C virus particles. The American journal of pathology 2006, 169, 200-208.

- de Witte, L.; Abt, M.; Schneider-Schaulies, S.; van Kooyk, Y.; Geijtenbeek, T.B.H. Measles virus targets DC-SIGN to enhance dendritic cell infection. Journal of virology 2006, 80, 3477-3486.

- de Jong, M.A.W.P.; de Witte, L.; Bolmstedt, A.; van Kooyk, Y.; Geijtenbeek, T.B.H. Dendritic cells mediate herpes simplex virus infection and transmission through the C-type lectin DC-SIGN. The Journal of general virology 2008, 89, 2398-2409.

- Mou, H.; Raj, V.S.; van Kuppeveld, F.J.M.; Rottier, P.J.M.; Haagmans, B.L.; Bosch, B.J. The receptor binding domain of the new Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus maps to a 231-residue region in the spike protein that efficiently elicits neutralizing antibodies. Journal of virology 2013, 87, 9379-9383.

- Goncalves, A.-R.; Moraz, M.-L.; Pasquato, A.; Helenius, A.; Lozach, P.-Y.; Kunz, S. Role of DC-SIGN in Lassa virus entry into human dendritic cells. Journal of virology 2013, 87, 11504-11515.

- Johnson, T.R.; McLellan, J.S.; Graham, B.S. Respiratory syncytial virus glycoprotein G interacts with DC-SIGN and L-SIGN to activate ERK1 and ERK2. Journal of virology 2012, 86, 1339-1347.

- Lozach, P.-Y.; Kuhbacher, A.; Meier, R.; Mancini, R.; Bitto, D.; Bouloy, M.; Helenius, A. DC-SIGN as a receptor for phleboviruses. Cell host & microbe 2011, 10, 75-88.

- Davis, C.W.; Nguyen, H.-Y.; Hanna, S.L.; Sanchez, M.D.; Doms, R.W.; Pierson, T.C. West Nile virus discriminates between DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR for cellular attachment and infection. Journal of virology 2006, 80, 1290-1301.

- Lin, G.; Simmons, G.; Pohlmann, S.; Baribaud, F.; Ni, H.; Leslie, G.J.; Haggarty, B.S.; Bates, P.; Weissman, D.; Hoxie, J.A., et al. Differential N-linked glycosylation of human immunodeficiency virus and Ebola virus envelope glycoproteins modulates interactions with DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR. J Virol 2003, 77, 1337-1346, doi:10.1128/jvi.77.2.1337-1346.2003.

- Carroll, M.V.; Sim, R.B.; Bigi, F.; Jakel, A.; Antrobus, R.; Mitchell, D.A. Identification of four novel DC-SIGN ligands on Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Protein Cell 2010, 1, 859-870, doi:10.1007/s13238-010-0101-3.

- Halary, F.; Amara, A.; Lortat-Jacob, H.; Messerle, M.; Delaunay, T.; Houles, C.; Fieschi, F.; Arenzana-Seisdedos, F.; Moreau, J.F.; Dechanet-Merville, J. Human cytomegalovirus binding to DC-SIGN is required for dendritic cell infection and target cell trans-infection. Immunity 2002, 17, 653-664, doi:10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00447-8.

- Gramberg, T.; Hofmann, H.; Moller, P.; Lalor, P.F.; Marzi, A.; Geier, M.; Krumbiegel, M.; Winkler, T.; Kirchhoff, F.; Adams, D.H., et al. LSECtin interacts with filovirus glycoproteins and the spike protein of SARS coronavirus. Virology 2005, 340, 224-236, doi:10.1016/j.virol.2005.06.026.

- Shimojima, M.; Stroher, U.; Ebihara, H.; Feldmann, H.; Kawaoka, Y. Identification of cell surface molecules involved in dystroglycan-independent Lassa virus cell entry. J Virol 2012, 86, 2067-2078, doi:10.1128/JVI.06451-11.

- Geijtenbeek, T.B.H.; Engering, A.; Van Kooyk, Y. DC-SIGN, a C-type lectin on dendritic cells that unveils many aspects of dendritic cell biology. J Leukoc Biol 2002, 71, 921-931.

- Geijtenbeek, T.B.; Kwon, D.S.; Torensma, R.; van Vliet, S.J.; van Duijnhoven, G.C.; Middel, J.; Cornelissen, I.L.; Nottet, H.S.; KewalRamani, V.N.; Littman, D.R., et al. DC-SIGN, a dendritic cell-specific HIV-1-binding protein that enhances trans-infection of T cells. Cell 2000, 100, 587-597.

- Moris, A.; Nobile, C.; Buseyne, F.; Porrot, F.; Abastado, J.-P.; Schwartz, O. DC-SIGN promotes exogenous MHC-I-restricted HIV-1 antigen presentation. Blood 2004, 103, 2648-2654.

- Turville, S.G.; Santos, J.J.; Frank, I.; Cameron, P.U.; Wilkinson, J.; Miranda-Saksena, M.; Dable, J.; Stossel, H.; Romani, N.; Piatak, M., Jr., et al. Immunodeficiency virus uptake, turnover, and 2-phase transfer in human dendritic cells. Blood 2004, 103, 2170-2179.

- Hijazi, K.; Wang, Y.; Scala, C.; Jeffs, S.; Longstaff, C.; Stieh, D.; Haggarty, B.; Vanham, G.; Schols, D.; Balzarini, J., et al. DC-SIGN increases the affinity of HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein interaction with CD4. PloS one 2011, 6, e28307.

- Burleigh, L.; Lozach, P.-Y.; Schiffer, C.; Staropoli, I.; Pezo, V.; Porrot, F.; Canque, B.; Virelizier, J.-L.; Arenzana-Seisdedos, F.; Amara, A. Infection of dendritic cells (DCs), not DC-SIGN-mediated internalization of human immunodeficiency virus, is required for long-term transfer of virus to T cells. Journal of virology 2006, 80, 2949-2957.

- Geijtenbeek, T.B.; Krooshoop, D.J.; Bleijs, D.A.; van Vliet, S.J.; van Duijnhoven, G.C.; Grabovsky, V.; Alon, R.; Figdor, C.G.; van Kooyk, Y. DC-SIGN-ICAM-2 interaction mediates dendritic cell trafficking. Nat Immunol 2000, 1, 353-357.

- Kwon, D.S.; Gregorio, G.; Bitton, N.; Hendrickson, W.A.; Littman, D.R. DC-SIGN-mediated internalization of HIV is required for trans-enhancement of T cell infection. Immunity 2002, 16, 135-144, doi:10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00259-5.

- McDonald, D.; Wu, L.; Bohks, S.M.; KewalRamani, V.N.; Unutmaz, D.; Hope, T.J. Recruitment of HIV and its receptors to dendritic cell-T cell junctions. Science 2003, 300, 1295-1297, doi:10.1126/science.1084238.

- McDonald, D.; Wu, L.; Bohks, S.M.; KewalRamani, V.N.; Unutmaz, D.; Hope, T.J. Recruitment of HIV and its receptors to dendritic cell-T cell junctions. Science (New York, N Y ) 2003, 300, 1295-1297.

- Cameron, P.U.; Freudenthal, P.S.; Barker, J.M.; Gezelter, S.; Inaba, K.; Steinman, R.M. Dendritic cells exposed to human immunodeficiency virus type-1 transmit a vigorous cytopathic infection to CD4+ T cells. Science (New York, N Y ) 1992, 257, 383-387.

- Cavrois, M.; Neidleman, J.; Greene, W.C. The achilles heel of the trojan horse model of HIV-1 trans-infection. PLoS pathogens 2008, 4, e1000051.

- Boukour, S.; Masse, J.M.; Benit, L.; Dubart-Kupperschmitt, A.; Cramer, E.M. Lentivirus degradation and DC-SIGN expression by human platelets and megakaryocytes. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH 2006, 4, 426-435.

- Chaipan, C.; Soilleux, E.J.; Simpson, P.; Hofmann, H.; Gramberg, T.; Marzi, A.; Geier, M.; Stewart, E.A.; Eisemann, J.; Steinkasserer, A., et al. DC-SIGN and CLEC-2 mediate human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capture by platelets. Journal of virology 2006, 80, 8951-8960.

- Rappocciolo, G.; Piazza, P.; Fuller, C.L.; Reinhart, T.A.; Watkins, S.C.; Rowe, D.T.; Jais, M.; Gupta, P.; Rinaldo, C.R. DC-SIGN on B lymphocytes is required for transmission of HIV-1 to T lymphocytes. PLoS pathogens 2006, 2, e70.

- Thépaut, M.; Luczkowiak, J.; Vivès, C.; Labiod, N.; Bally, I.; Lasala, F.; Grimoire, Y.; Fenel, D.; Sattin, S.; Thielens, N., et al. DC/L-SIGN recognition of spike glycoprotein promotes SARS-CoV-2 trans-infection and can be inhibited by a glycomimetic antagonist. bioRxiv 2020, 10.1101/2020.08.09.242917, 2020.2008.2009.242917, doi:10.1101/2020.08.09.242917.

- Hodges, A.; Sharrocks, K.; Edelmann, M.; Baban, D.; Moris, A.; Schwartz, O.; Drakesmith, H.; Davies, K.; Kessler, B.; McMichael, A., et al. Activation of the lectin DC-SIGN induces an immature dendritic cell phenotype triggering Rho-GTPase activity required for HIV-1 replication. Nat Immunol 2007, 8, 569-577.

- Gringhuis, S.I.; den Dunnen, J.; Litjens, M.; van Het Hof, B.; van Kooyk, Y.; Geijtenbeek, T.B.H. C-type lectin DC-SIGN modulates Toll-like receptor signaling via Raf-1 kinase-dependent acetylation of transcription factor NF-kappaB. Immunity 2007, 26, 605-616.

- Geijtenbeek, T.B.H.; Gringhuis, S.I. Signalling through C-type lectin receptors: shaping immune responses. Nature reviews Immunology 2009, 9, 465-479.

- Delmas, B.; Gelfi, J.; L'Haridon, R.; Vogel, L.K.; Sjostrom, H.; Noren, O.; Laude, H. Aminopeptidase N is a major receptor for the entero-pathogenic coronavirus TGEV. Nature 1992, 357, 417-420.

- Yeager, C.L.; Ashmun, R.A.; Williams, R.K.; Cardellichio, C.B.; Shapiro, L.H.; Look, A.T.; Holmes, K.V. Human aminopeptidase N is a receptor for human coronavirus 229E. Nature 1992, 357, 420-422.

- Matrosovich, M.; Herrler, G.; Klenk, H.D. Sialic Acid Receptors of Viruses. Top Curr Chem 2015, 367, 1-28.

- Huang, X.; Dong, W.; Milewska, A.; Golda, A.; Qi, Y.; Zhu, Q.K.; Marasco, W.A.; Baric, R.S.; Sims, A.C.; Pyrc, K., et al. Human Coronavirus HKU1 Spike Protein Uses O-Acetylated Sialic Acid as an Attachment Receptor Determinant and Employs Hemagglutinin-Esterase Protein as a Receptor-Destroying Enzyme. Journal of virology 2015, 89, 7202-7213.

- Raj, V.S.; Mou, H.; Smits, S.L.; Dekkers, D.H.W.; Muller, M.A.; Dijkman, R.; Muth, D.; Demmers, J.A.A.; Zaki, A.; Fouchier, R.A.M., et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is a functional receptor for the emerging human coronavirus-EMC. Nature 2013, 495, 251-254.

- Chan, C.-M.; Chu, H.; Wang, Y.; Wong, B.H.-Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, J.; Yang, D.; Leung, S.P.; Chan, J.F.-W.; Yeung, M.-L., et al. Carcinoembryonic Antigen-Related Cell Adhesion Molecule 5 Is an Important Surface Attachment Factor That Facilitates Entry of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. Journal of virology 2016, 90, 9114-9127.

- Marzi, A.; Gramberg, T.; Simmons, G.; Moller, P.; Rennekamp, A.J.; Krumbiegel, M.; Geier, M.; Eisemann, J.; Turza, N.; Saunier, B., et al. DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR interact with the glycoprotein of Marburg virus and the S protein of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Journal of virology 2004, 78, 12090-12095.

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S.; Kruger, N.; Herrler, T.; Erichsen, S.; Schiergens, T.S.; Herrler, G.; Wu, N.H.; Nitsche, A., et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271-280 e278, doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052.

- Hofmann, H.; Pyrc, K.; van der Hoek, L.; Geier, M.; Berkhout, B.; Pohlmann, S. Human coronavirus NL63 employs the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus receptor for cellular entry. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2005, 102, 7988-7993.

- Li, W.; Moore, M.J.; Vasilieva, N.; Sui, J.; Wong, S.K.; Berne, M.A.; Somasundaran, M.; Sullivan, J.L.; Luzuriaga, K.; Greenough, T.C., et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature 2003, 426, 450-454.

- Han, D.P.; Lohani, M.; Cho, M.W. Specific asparagine-linked glycosylation sites are critical for DC-SIGN- and L-SIGN-mediated severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus entry. Journal of virology 2007, 81, 12029-12039.

- Jeffers, S.A.; Tusell, S.M.; Gillim-Ross, L.; Hemmila, E.M.; Achenbach, J.E.; Babcock, G.J.; Thomas, W.D., Jr.; Thackray, L.B.; Young, M.D.; Mason, R.J., et al. CD209L (L-SIGN) is a receptor for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2004, 101, 15748-15753.

- Soh, W.T.; Liu, Y.; Nakayama, E.E.; Ono, C.; Torii, S.; Nakagami, H.; Matsuura, Y.; Shioda, T.; Arase, H. The N-terminal domain of spike glycoprotein mediates SARS-CoV-2 infection by associating with L-SIGN and DC-SIGN. bioRxiv 2020, 10.1101/2020.11.05.369264, 2020.2011.2005.369264, doi:10.1101/2020.11.05.369264.

- Gao, C.; Zeng, J.; Jia, N.; Stavenhagen, K.; Matsumoto, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Hume, A.J.; Muhlberger, E.; van Die, I., et al. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Interacts with Multiple Innate Immune Receptors. bioRxiv 2020, 10.1101/2020.07.29.227462, doi:10.1101/2020.07.29.227462.

- Chiodo, F.; Bruijns, S.C.M.; Rodriguez, E.; Li, R.J.E.; Molinaro, A.; Silipo, A.; Di Lorenzo, F.; Garcia-Rivera, D.; Valdes-Balbin, Y.; Verez-Bencomo, V., et al. Novel ACE2-Independent Carbohydrate-Binding of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein to Host Lectins and Lung Microbiota. bioRxiv 2020, 10.1101/2020.05.13.092478, 2020.2005.2013.092478, doi:10.1101/2020.05.13.092478.

- Snyder, G.A.; Colonna, M.; Sun, P.D. The structure of DC-SIGNR with a portion of its repeat domain lends insights to modeling of the receptor tetramer. Journal of molecular biology 2005, 347, 979-989.

- Sol-Foulon, N.; Moris, A.; Nobile, C.; Boccaccio, C.; Engering, A.; Abastado, J.P.; Heard, J.M.; van Kooyk, Y.; Schwartz, O. HIV-1 Nef-induced upregulation of DC-SIGN in dendritic cells promotes lymphocyte clustering and viral spread. Immunity 2002, 16, 145-155, doi:10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00260-1.

- Mitchell, D.A.; Fadden, A.J.; Drickamer, K. A novel mechanism of carbohydrate recognition by the C-type lectins DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR. Subunit organization and binding to multivalent ligands. J Biol Chem 2001, 276, 28939-28945, doi:10.1074/jbc.M104565200.

- Cambi, A.; de Lange, F.; van Maarseveen, N.M.; Nijhuis, M.; Joosten, B.; van Dijk, E.M.; de Bakker, B.I.; Fransen, J.A.; Bovee-Geurts, P.H.; van Leeuwen, F.N., et al. Microdomains of the C-type lectin DC-SIGN are portals for virus entry into dendritic cells. J Cell Biol 2004, 164, 145-155, doi:10.1083/jcb.200306112.

- Yu, Q.D.; Oldring, A.P.; Powlesland, A.S.; Tso, C.K.; Yang, C.; Drickamer, K.; Taylor, M.E. Autonomous tetramerization domains in the glycan-binding receptors DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR. J Mol Biol 2009, 387, 1075-1080, doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2009.02.046.

- Feinberg, H.; Tso, C.K.; Taylor, M.E.; Drickamer, K.; Weis, W.I. Segmented helical structure of the neck region of the glycan-binding receptor DC-SIGNR. J Mol Biol 2009, 394, 613-620, doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2009.10.006.

- Drickamer, K.; Taylor, M.E. Recent insights into structures and functions of C-type lectins in the immune system. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2015, 34, 26-34, doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2015.06.003.